Abstract

Family health history (FHH) can serve as an entry point for preventive medicine by providing risk estimations for many common health conditions. College is a critical time for young adults to begin to understand the value of FHH collection, and to establish healthy behaviors to prevent FHH-related diseases. This study seeks to develop an integrated theoretical framework to examine FHH collection behavior and associated factors among college students. A sample of 2670 college students with an average age of 21.1 years completed a web-based survey. Less than half (49.8%) reported actively seeking FHH information from their family members. Respondents’ knowledge about FHH were generally low. Structural equation modeling findings suggested an adequate model fit between our survey data and the proposed integrated theoretical framework. Respondents who were members of racial/ethnic minority groups exhibited higher levels of anxiety and intention to obtain FHH information but had lower confidence in their ability to gather FHH information than non-Hispanic White respondents. Therefore, educational programs designed to enhance the level of young adults’ FHH knowledge, efficacy, and behavior in FHH collection, and change subjective norms are critically needed in the future, especially for these who are members of racial/ethnic minority groups.

1. Introduction

Family health history (FHH) is a significant risk factor associated with many common and multifactorial health conditions such as cancer, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes because it can capture genetic, behavioral, and environmental factors associated with these diseases that run in one’s family [1,2]. College is a critical time for young adults aged from 18 to 35 years to seek FHH information from family members for a number of reasons. First, the incidence and earlier onset of many of the chronic diseases related to FHH (e.g., obesity, cancer, and type 2 diabetes) are increasing [3,4,5]. Given that FHH can be used to assess disease risks [6], college students who are unaware of their FHH may not recognize potential health threats and be able to take timely preventive actions. Second, the period in which young people pursue post-secondary education is an ideal time to establish future lifestyle-related behaviors [7]. FHH can provide critical information that can help college students establish healthy behaviors early in life that can result in a significant, positive impact on their future health. Third, the research literature has shown that FHH can motivate individuals to adopt healthier behaviors [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Thus, FHH information may encourage college students to improve their levels of exercise and healthy eating, maintain an appropriate weight, and reduce alcohol intake. Fourth, young adults in college are at the ideal time in their lives to quickly learn and apply new knowledge [15], and become more comfortable in sharing vital information in FHH communication [16]. Those who collect and share FHH information may influence other family members to also discuss and collect FHH which will result in the creation of a more comprehensive FHH [16,17]. Lastly, with the current increased application of genetic tests in precision medicine for disease prevention, diagnosis, and treatment [18], FHH information can help physicians to determine the needs of genetic tests for college students.

Although it is important for college students to gather their FHH, few studies have assessed this behavior [17,19,20,21]. A survey study at a university setting [17] showed that a majority of the young adult respondents were aware of FHH, but fewer than 40% had collected it. In another survey study, Smith and colleagues [19] reported that female college students were more likely to seek FHH information and share it with family members than were male students, but they also found that both groups perceived barriers to collect FHH. The other two studies investigated FHH information seeking intention among young adults using the Theory of Motivated Information Management (TMIM). In alignment with TMIM principles, both these studies found that FHH related uncertainty discrepancy (the discrepancy between individuals’ actual and desired level of uncertainty) and associated emotional factors (e.g., anxiety and distress) were linked with young adults’ intention to seek FHH information [20,21]. These findings also suggested that FHH collection was a complex behavior that was impacted by several sociodemographic and psychological factors.

Based upon the results of the studies described above, this study aims to develop and examine an integrated theoretical framework that can be used to assess college students’ FHH collection behavior. Given that FHH collection is a complex behavior [20,21], the development of an integrated theoretical framework encompassing multiple levels (i.e., interpersonal and intrapersonal health behaviors and health communication) has the potential to make a significant contribution to improving our understanding of FHH collection behavior [22]. The purposes of this study are threefold. First, we seek to assess young adults’ behavior in FHH collection from family members. Second, we attempt to examine the psychological factors associated with such behavior using an integrated theoretical framework. Third, we will test if sociodemographic characteristics and FHH knowledge are correlated to FHH collection behavior among young adults.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

This study was approved by the Texas A&M University Institutional Review Board. Participation criteria included undergraduate or graduate student enrollment at two campuses of a public research-intensive university, and persons aged 18–35 years to meet the definition of young adult [23]. We used Qualtrics (http://www.qualtrics.com (accessed from 15 October 2018 to 20 November 2018)) to collect survey data. Responses were anonymous and participation was voluntary. All participants who completed the survey were given the opportunity to enter a drawing for one of 40 available $50 electronic gift cards as an incentive to participate. The first 100 participants who completed the survey received an additional $5 electronic gift card. To protect participant privacy, participants who wished to be entered in the drawing for electronic gift card incentives were linked to a separate survey to enter their names and emails for incentives that was not in any way associated with the initial survey. We used the university bulk email service to send the initial recruitment email and three reminder emails with the survey link to 55,295 college students. A total of 2809 students filled out the survey, which yielded a response rate of 5.08%.

2.2. Survey Development

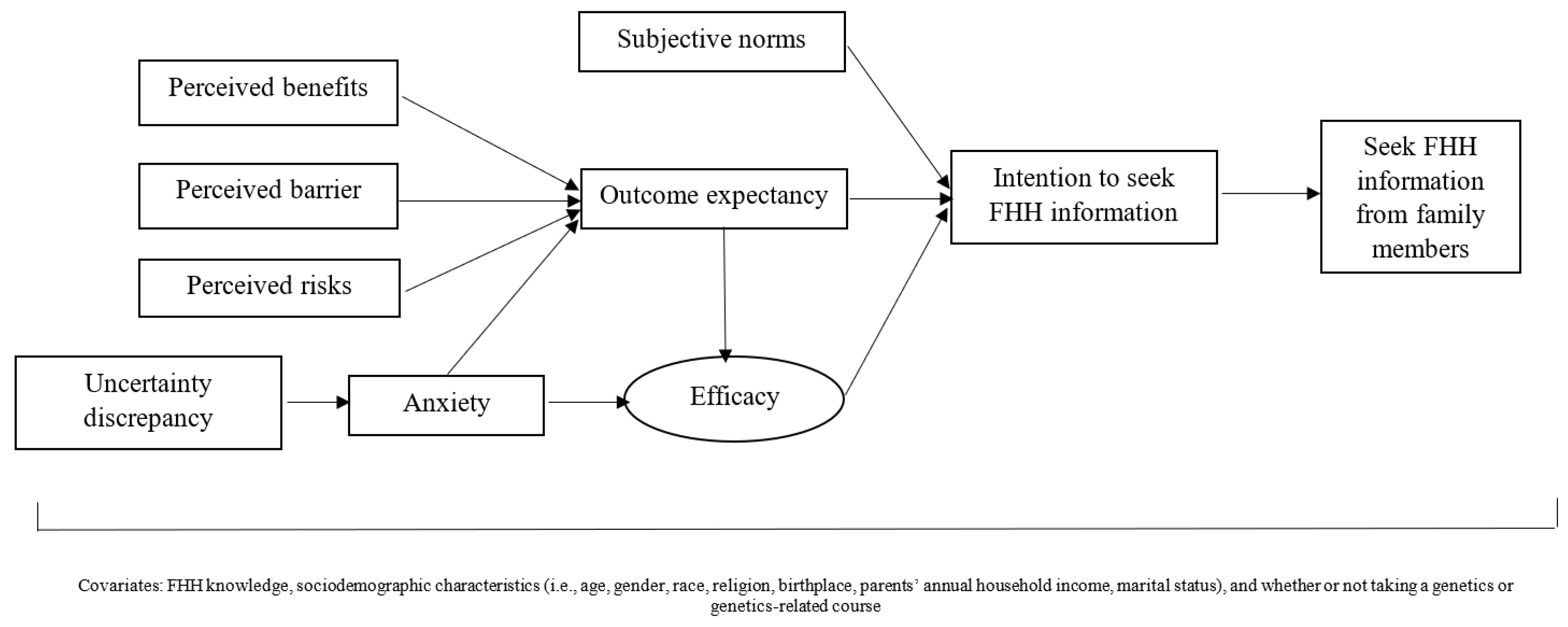

We developed a 15-min web-based survey based on the integrated theoretical framework and previous literature [19,20,21,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. The constructs in the integrated theoretical framework (Figure 1) were adopted from the key health behavior and communication theories related to FHH collection used in previous studies (i.e., the Health Behavior Model, the Theory of Planned Behavior, and the TMIM) [19,20,21,32]. As presented in Figure 1, subjective norms, outcome expectancy, and efficacy in FHH collection from family members were correlated with young adults’ intention to seek FHH information, which was directly associated to the behavior of FHH collection. Outcome expectancy regarding FHH collection was associated with young adults’ perceptions of the benefits of and barriers to FHH collection, their risk perceptions of developing diseases that run in one’s family, and anxiety resulting from the uncertainties involved in the unknown FHH. Moreover, efficacy was associated with both outcome expectancy and anxiety, which was also linked with uncertainty discrepancy toward FHH information. The definition and detailed measures are described in Table 1. In addition, sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, birthplace, race/ethnicity, religion, and marital status), FHH knowledge (Table 2), and whether or not respondents had taken a genetics or genetics-related course as a college or graduate student were measured in the survey and added to the SEM model as moderator variables to determine the effect that those factors had on FHH collection behavior [19,33,34].

Figure 1.

Proposed integrated theoretical model of FHH information seeking behavior among young adults. FHH: family health history.

Table 1.

Definitions, description, examples, and data reliability and validity of the psychological constructs measured in the survey.

Table 2.

FHH knowledge among college students in our sample.

2.3. Survey Pre-Test

To ensure content validity, experts from multiple related fields including statistics, health education, health communication, college health, and public health genomics reviewed the survey. The survey was then revised based on their feedback. Subsequently, cognitive interviews with a convenience sample of nine college students, and retrospective interviews with additional eight college students were conducted. Minor changes that were made to the survey addressed wording, clarity, and formatting issues. The revised survey was then pilot tested with 63 young adults recruited from two undergraduate classes. The final version of the survey included 16 sections with 95 items. The data collected in the pilot test showed adequate data validity and reliability. We did make minor revisions to the wording of the uncertainty discrepancy items to improve clarity.

2.4. Data Analysis Strategies

Survey data cleaning, missingness, descriptive statistics, and psychometric testing (validity using confirmatory factor analysis and reliability using Cronbach’s alpha) were conducted using STATA 15 (Stata, College Station, TX, USA). Missing data analysis was performed to examine any difference between respondents who completed only the demographic information, and those who completed or partially completed the remaining survey [35]. Psychometric testing of each psychological construct showed acceptable data reliability and validity (Figure 1). Bivariate correlations were conducted to examine the relationships between main dependent variables of the psychological constructs (i.e., anxiety, outcome expectancy, efficacy, intention, and behavior in FHH collection) and covariates (i.e., sociodemographic characteristics, FHH knowledge, and whether or not the respondent had taken genetics/genetics-related courses in college). Those covariates with significant bivariate associations with the main psychological constructs were included in the final SEM model. M-plus 8.0 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA) was used to analyze the relationships among the constructs in the proposed theoretical framework [36]. Because chi-square is sensitive to large sample sizes [37], model fit was assessed using three fit indices including the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and standardized root mean residual (SRMR). In this study, a RMSEA < 0.08, a CFI > 0.90, and a SRMR < 0.06, were adopted as the cut-off points for an adequate model fit [38].

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

We excluded the responses of 139 participants who completed only the sociodemographic information portion of the survey from the final sample. The final sample consisted of 2670 young adults with the average age of 21.0 years (SD = 3.4, range = 18–35). A majority of respondents were female (66.3%) and born in the United States (78.4%). Approximately half were self-identified as non-Hispanic White (44.9%). Nearly two-thirds of the participants (64.3%) practiced Christian. About one fourth (23.2%) reported no religious affiliation, and the remaining 12.5% practiced other religions, such as Hinduism, Muslim, and Buddhism. About half of participants reported that they had taken a genetics course in college (15.0%) or were currently or previously enrolled in a course containing genetics-related information (32.7%). We used six true/false items to measure FHH knowledge and respondents’ average correct rate was 57.8%. Table 2 presents the percentage of correct answers for each FHH knowledge item. Moreover, the mean score (5.2 ± 1.3) was high for the participants’ perception of importance of FHH collection, which suggested that respondents believed that seeking FHH information from their family members was important. As issue importance is a necessary condition of the TMIM, the high mean score indicates that the condition was met in our sample.

3.2. Behavior in FHH Collection with Family Members

Slightly less than half (49.8%) reported actively sought FHH information from their family members. The remaining participants in our sample reported that they had never, rarely, or occasionally sought FHH information from their family members during the past six months.

3.3. Psychological Factors Associated with FHH Collection Behavior: SEM Findings

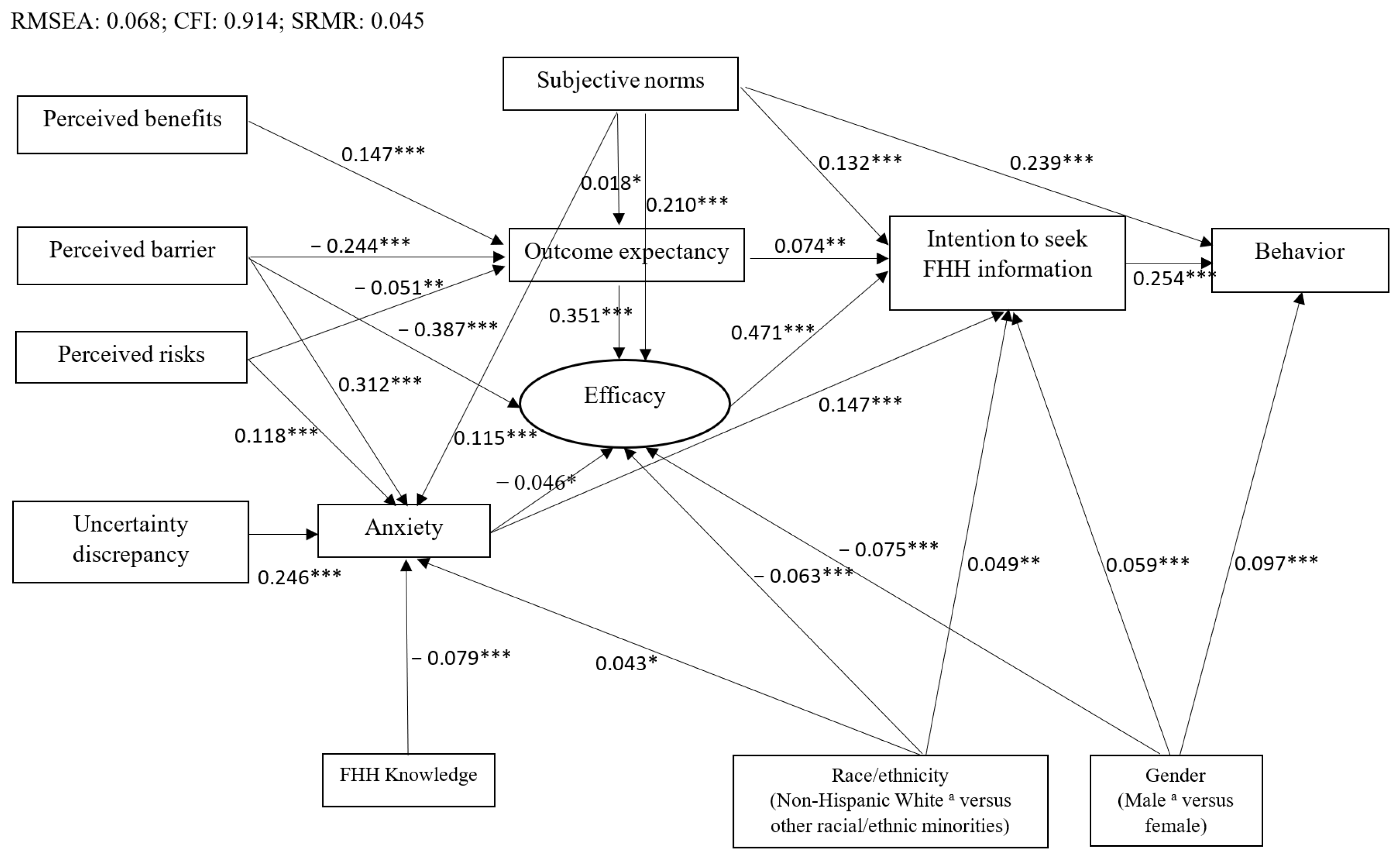

Figure 2 shows the final SEM findings. In particular, the SEM model fit the survey data adequately based on the model fit indices (i.e., RMSEA = 0.068; CFI = 0.914; SRMR = 0.045). Stronger intention to seek FHH information and perception of the high level of subjective norms toward FHH collection were correlated with participants’ FHH collection behavior (β = 0.254, p < 0.001 and β = 0.239, p < 0.001, respectively). Efficacy in FHH collection, anxiety associated with the uncertainty of FHH, subjective norms, and outcome expectancy of the consequences of FHH collection were significantly and positively associated with respondents’ intention to collect FHH information (β = 0.471, p < 0.001; β = 0.147, p < 0.001; β = 0.132, p < 0.001; and β = 0.074, p < 0.001, respectively). Outcome expectancy and subjective norms were positively correlated with efficacy in FHH collection (β = 0.351, p < 0.001 and β = 0.210, p < 0.001, respectively), while perceived barriers to FHH collection from family members was negatively associated with efficacy (β = −0.387, p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

SEM model for FHH information seeking behavior among college students. p < 0.001 ***, p < 0.005 **, p < 0.05 *. The figure only presented the statistically significant associations (solid lines) and standardized coefficients. a Reference group. SEM: Structural equation modeling; FHH: family health history.

Perceived benefits of FHH collection and subjective norms were significantly and positively associated with outcome expectancy toward FHH collection (β = 0.147, p < 0.001 and β = 0.018, p < 0.05, respectively). However, perceived barriers to FHH collection from family members and perceived risks of developing diseases that run in a family were negatively associated with outcome expectancy (β = −0.244, p < 0.001 and β = −0.051, p < 0.005, respectively). Perceived barriers to FHH collection from family members, uncertainty discrepancy, perceived risks of getting diseases that run in families, and subjective norms were significantly and positively associated with anxiety with the uncertainty of FHH (β = 0.312, p < 0.001; β = 0.246, p < 0.001; β = 0.118, p < 0.001; and β = 0.115, p < 0.001, respectively).

3.4. Whether or Not Sociodemographic Characteristics and FHH Knowledge Were Correlated to FHH Collection Behavior

As shown in Figure 2, female young adults in this study were more likely to collect, and to actually collect their FHH from family members when compared to their male counterparts (β = 0.059, p < 0.001; β = 0.097, p < 0.001, respectively). Furthermore, participants who were members of racial and ethnic minority groups had a higher level of anxiety associated with lacking FHH information (β = 0.043, p < 0.05) and stronger intention to collect their FHH (β = 0.049, p < 0.005), but had lower efficacy in FHH collection (β = −0.063, p < 0.001) than non-Hispanic White respondents. Respondents with better FHH knowledge reported less anxiety (β = −0.079, p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

In light of the importance of FHH collection from family members among young adults, we sought to develop and test an integrated theoretical framework that could be used to examine college students’ FHH collection behavior and underlying factors using a large sample from two campuses of a public research-intensive university. Consistent with national data collected through surveying adults over the age of 18 [39] and previous research studying young adults [17], a majority of participants in our study considered collecting FHH important. However, less than half of participants (49.8%) reported actively seeking FHH information from their family members in the previous six months. Our finding is in line with previous studies. For example, a national survey of 5258 adults in the U.S. reported that only 36.9% of the respondents have actively collected their FHH [40]. Studies that were conducted to assess the use of FHH among underserved populations, such as Latinxs, African Americans, and Chinese Americans, also indicated that many of their participants had seldom collected FHH [32,41,42].

Along with a lack of FHH collection behavior from family members, we also found that our participants had low levels of FHH knowledge. In particular, only 21.8% of the respondents knew that their biological siblings are considered first-degree relatives. Moreover, about two-thirds of participants mistakenly thought that people are more similar genetically to their parents than to their brothers or sisters. This finding is aligned with a past study carried out by Rooks and Ford [43] which showed that most college students had low levels of FHH knowledge. As such, it is important to develop and implement interventions and educational programs to improve college students’ FHH knowledge and motivate them to gather FHH information from their family members.

Our SEM findings showed that young adults’ participation in FHH information collection from their family members was significantly and directly associated with their intention and likelihood to seek FHH information, and that intention to solicit FHH information was also significantly related to respondents’ efficacy in FHH communication with family members and outcome expectancy toward FHH collection. Additionally, social pressures on the participants (i.e., subjective norms) played an important role in both their FHH collection behavior and intention. Higher levels of FHH knowledge among participants was also related to lower levels of anxiety caused by FHH uncertainties. Therefore, when developing an FHH intervention and educational program, both individual factors (e.g., FHH knowledge, intention to pursue FHH information, efficacy in FHH communication, and outcome expectancy toward FHH collection) and social factors (i.e., subjective norms) should be considered. For example, a previous study has shown that family-level interventions, which take social factors into consideration, were effective in the adoption and diffusion of health behaviors [44]. As suggested, a family-based FHH intervention, which includes both young adults and other family members, may address both the individual and social factors affecting FHH collection among young adults. Given that obtaining a comprehensive and accurate FHH requires effort from all family members [44], the family unit is the ideal context for an FHH intervention.

Interestingly, our study results revealed that although racial/ethnic minority young adults exhibited both higher levels of anxiety related to unknown FHH information and more intention to gather their FHH from their family members when compared to their non-Hispanic White counterparts, they had lower efficacy in FHH collection. These findings suggested that FHH interventions and educational programs should be designed with sensitivity to the specific needs of young adult members of race/ethnicity minority groups with a goal of improving their skills, confidence and coping strategies, and reducing their anxiety levels when gathering FHH from their families. In alignment with previously published articles [19,24,32,34], female respondents in our sample were more likely to collect, and to actually collect FHH information from family members than were their male counterparts. Thus, future FHH interventions and educational programs should attempt to recruit young adult males to improve their FHH collection intention and behavior.

This study has several limitations. First, the generalizability of our findings may be limited due to the fact that participants were recruited from two campuses of one public research-intensive university. Second, this study might have a potential sample selection bias as those who responded to the survey might have had higher levels of awareness and been more interested in FHH than those who opted not to participate in our study. Third, due to the nature of cross-section surveys, we were unable to ascertain causal relationships between each construct in Figure 2. A longitudinal study is recommended in the future to examine the causal relationships. Fourth, the response rates for web-based surveys tend to be low (from 2.07% to 31.54%) in a college setting [45,46]. We employed multiple strategies to increase the response rate (e.g., providing incentives and sending three follow-up reminder emails) [47]. As expected, however, the response rate of our web-based survey was low (5.08%), but was within the range of those reported in previous studies. The possible reasons for this low response rate might be that college students did not frequently check their university email accounts, received too many emails each day, ignored messages sent from the university bulk email system, had settings on their account that sent our email directly to a spam folder, lacked interest in this study, or were busy doing their coursework and studying for their examinations [45].

Despite the above limitations, this study makes an important contribution to the limited extant research focused on understanding young adults’ FHH collection behavior and the psychological factors associated with this behavior. Consistent with the literature [17,43], our data showed that the young adults in our sample lacked FHH collection and had a deficient knowledge of FHH. Thus, it is of critical importance that FHH interventions and educational programs should be designed for and disseminated to this particular group in the future. Additionally, we created an integrated theoretical framework to examine young adults’ behavior in FHH collection, which was then tested with a large sample (over 2000 participants). The SEM findings supported the applicability of our proposed integrated theoretical framework. Psychosocial factors (i.e., intention, efficacy, outcome expectancy, subjective norms, anxiety, uncertainty discrepancy, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, perceived risks, and uncertainty discrepancy), FHH knowledge, and sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., gender, and race/ethnicity) were significantly associated with FHH collection behavior among young adults in both direct and indirect ways. Our SEM findings provide a foundation for the design and development of FHH interventions and educational programs for young adults in the future. Furthermore, it is highly recommended that these interventions and educational programs should target males, and be designed with sensitivity to the specific needs of young adult members of racial/ethnic minority and other traditionally underserved groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L. and L.-S.C.; methodology, M.L. and L.-S.C.; formal analysis, M.L., L.-S.C., S.Z., Y.-Y.H. and O.-M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.; writing—review and editing, L.-S.C., M.L., S.Z., Y.-Y.H., O.-M.K. and T.-S.T.; funding acquisition, L.-S.C. and M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the College of Education and Human Development and the Huffines Institute for Sports Medicine and Human Performance at Texas A&M University. The APC (article processing charge) was funded by Texas A&M University and Towson University College of Health Professions SURI funds.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Texas A & M University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

As a data sharing strategy was not included in the original application for institutional review board review, study data are not publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Guttmacher, A.E.; Collins, F.S.; Carmona, R.H. The family history—More important than ever. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 2333–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdez, R.; Yoon, P.W.; Qureshi, N.; Green, R.F.; Khoury, M.J. Family history in public health practice: A genomic tool for disease prevention and health promotion. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2010, 31, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahnen, D.J.; Wade, S.W.; Jones, W.F.; Sifri, R.; Mendoza Silveiras, J.; Greenamyer, J.; Guiffre, S.; Axilbund, J.; Spiegel, A.; You, Y.N. The increasing incidence of young-onset colorectal cancer: A call to action. Mayo Clinic. Proc. 2014, 89, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmot, E.; Idris, I. Early onset type 2 diabetes: Risk factors, clinical impact and management. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2014, 5, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Siegel, R.L.; Rosenberg, P.S.; Jemal, A. Emerging cancer trends among young adults in the USA: Analysis of a population-based cancer registry. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e137–e147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Chen, J.; Shen, B. Interactions between genetics, lifestyle, and environmental factors for healthcare. In Translational Informatics in Smart Healthcare; Shen, B., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 167–191. [Google Scholar]

- Plotnikoff, R.C.; Costigan, S.A.; Williams, R.L.; Hutchesson, M.J.; Kennedy, S.G.; Robards, S.L.; Allen, J.; Collins, C.E.; Callister, R.; Germov, J. Effectiveness of interventions targeting physical activity, nutrition and healthy weight for university and college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claassen, L.; Henneman, L.; Janssens, A.C.J.; Wijdenes-Pijl, M.; Qureshi, N.; Walter, F.M.; Yoon, P.W.; Timmermans, D.R.M. Using family history information to promote healthy lifestyles and prevent diseases; a discussion of the evidence. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhao, S.; Young, C.M.; Foster, M.; Wang, J.H.-Y.; Tseng, T.-S.; Kwok, O.-M.; Chen, L.-S. Family health history–based interventions: A systematic review of the literature. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 61, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, C.; Carthron, D.L.; Duren-Winfield, V.; Lawrence, W. An experiential cardiovascular health education program for African American college students. ABNF J. 2014, 25, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, P.J.; Gratzer, W.; Lieber, C.; Edelson, V.; O’Leary, J.; Terry, S.F. Iona college community centered family health history project: Lessons learned from student focus groups. J. Genet Couns. 2012, 21, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, P.J.; Gratzer, W.; Lieber, C.; Edelson, V.; O’Leary, J.; Terry, S.F.; Grudzen, M.; Hikoyeda, N. Does it run in the family? Toolkit: Improving well-educated elders ability to facilitate conversations about family health history. Am. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ruffin, M.T.; Nease, D.E., Jr.; Sen, A.; Pace, W.D.; Wang, C.; Acheson, L.S.; Rubinstein, W.S.; O’Neill, S.; Gramling, R.U.; Family Healthware Impact Trial Group. Effect of preventive messages tailored to family history on health behaviors: The Family Healthware Impact Trial. Ann. Fam. Med. 2011, 9, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijdenes, M.; Henneman, L.; Qureshi, N.; Kostense, P.J.; Cornel, M.C.; Timmermans, D.R.M.U. Using web-based familial risk information for diabetes prevention: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Salome, G.; Rauscher, E.A.; Freytag, J. Patterns of communicating about family health history: Exploring differences in family types, age, and sex. Health Educ. Behav. 2019, 46, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhavan, S.; Bullis, E.; Myers, R.; Zhou, C.J.; Cai, E.M.; Sharma, A.; Bhatia, S.; Orlando, L.A.; Haga, S.B. Awareness of family health history in a predominantly young adult population. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, S.J.; Rehm, H.L. Building the foundation for genomics in precision medicine. Nature 2015, 526, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.L.; Beaudoin, C.E.; Sosa, E.T.; Pulczinski, J.C.; Ory, M.G.; McKyer, E.L.J. Motivations, barriers, and behaviors related to obtaining and discussing family health history: A sex-based comparison among young adults. Front. Public Health 2015, 3, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovick, S.R. Understanding family health information seeking: A test of the theory of motivated information management. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauscher, E.A.; Hesse, C. Investigating uncertainty and emotions in conversations about family health history: A test of the theory of motivated information management. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19, 939–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, C.H.; Shiloh, S.; Woolford, S.W.; Roberts, J.S.; Alford, S.H.; Marteau, T.M.; Biesecker, B.B. Modelling decisions to undergo genetic testing for susceptibility to common health conditions: An ancillary study of the Multiplex Initiative. Psychol. Health 2012, 27, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petry, N.M. A comparison of young, middle-aged, and older adult treatment-seeking pathological gamblers. Gerontologist 2002, 42, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaphingst, K.A.; Lachance, C.R.; Gepp, A.; D’Anna, L.H.; Rios-Ellis, B.U. Educating underserved Latino communities about family health history using lay health advisors. Public Health Genom. 2011, 14, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christianson, C.A.; Powell, K.P.; Hahn, S.E.; Bartz, D.; Roxbury, T.; Blanton, S.H.; Vance, J.M.; Pericak-Vance, M.; Telfair, J.; Henrich, V.C. Findings from a community education needs assessment to facilitate the integration of genomic medicine into primary care. Genet. Med. 2010, 12, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbons, A.; Groarke, A. Can risk and illness perceptions predict breast cancer worry in healthy women? J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 2052–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, E.W.; Pinkleton, B.E.; Weintraub Austin, E.; Reyes-Velázquez, W. Exploring college students’ use of general and alcohol-related social media and their associations with alcohol-related behaviors. J. Am. Coll. Health 2014, 62, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussner, K.M.; Jandorf, L.; Valdimarsdottir, H.B. Educational needs about cancer family history and genetic counseling for cancer risk among frontline healthcare clinicians in New York City. Genet. Med. 2011, 13, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Health Information National Trends Survey Cycle 1. Available online: https://hints.cancer.gov/docs/Instruments/HINTS5_Cycle1_Annotated_Instrument_English.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Family Health History: The Basics. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/famhistory/famhist_basics.htm (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- National Human Genome Research Institute. The U.S. Surgeon General’s Family History Initiative: My Family Health Portrait. Available online: https://www.genome.gov/17516481/the-us-surgeon-generals-family-history-initiative-family-history-initiative/ (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Yeh, Y.-L.; Li, M.; Kwok, O.-M.; Chen, L.-S. Family health history of colorectal cancer: A structural equation model of factors influencing Chinese Americans’ communication with family members. Transl. Cancer Res. 2019, 8 (Suppl. 4), S355–S365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, M.W.; Goodson, P.; Goltz, H.H. Exploring genetic numeracy skills in a sample of U.S. university students. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehly, L.M.; Peters, J.A.; Kenen, R.; Hoskins, L.M.; Ersig, A.L.; Kuhn, N.R.; Loud, J.T.; Greene, M.H. Characteristics of health information gatherers, disseminators, and blockers within families at risk of hereditary cancer: Implications for family health communication interventions. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 2203–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhi, E.R.; Goodson, P.; Neilands, T.B. Out of sight, not out of mind: Strategies for handling missing data. Am. J. Health Behav. 2008, 32, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthen, L. Mplus User’s Guide 1998–2012; Muthen & Muthen: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016.

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, P.; Scheuner, M.T.; Gwinn, M.; Khoury, M.J.; Jorgensen, C. Awareness of family health history as a risk factor for disease. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2004, 53, 1044–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, B.M.; O’Connell, N.; Schiffman, J.D. 10 years later: Assessing the impact of public health efforts on the collection of family health history. Am. J. Med. Genet A 2015, 167A, 2026–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaphingst, K.A.; Goodman, M.; Pandya, C.; Garg, P.; Stafford, J.; Lachance, C. Factors affecting frequency of communication about family health history with family members and doctors in a medically underserved population. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 88, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.S.; Li, M.; Talwar, D.; Xu, L.; Zhao, M. Chinese Americans’ views and use of family health history: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooks, R.; Ford, C. Family health history and behavioral change among undergraduate students: A mixed methods study. Health 2016, 8, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Heer, H.D.; de la Haye, K.; Skapinsky, K.; Goergen, A.F.; Wilkinson, A.V.; Koehly, L.M. Let’s move together: A randomized trial of the impact of family health history on encouragement and co-engagement in physical activity of Mexican-origin parents and their children. Health Educ. Behav. 2017, 44, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrell, H.E.R.; Cohen, L.M.; Bacchi, D.; West, J. Predictors of smoking and smokeless tobacco use in college students: A preliminary study using web-based survey methodology. J. Am. Coll. Health 2005, 54, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primack, B.A.; Sidani, J.; Carroll, M.V.; Fine, M.J. Associations between smoking and media literacy in college students. J. Health Commun. 2009, 14, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).