Transcriptional Modulation during Photomorphogenesis in Rice Seedlings

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material, Growth Conditions, and Treatment

2.2. Sample Preparation and Sequencing

2.3. RNA-seq Data Analysis

2.4. Functional Annotation

2.5. Alternative Splicing Analysis

2.6. Prediction of Long Non-Coding RNA (lncRNA)

3. Results

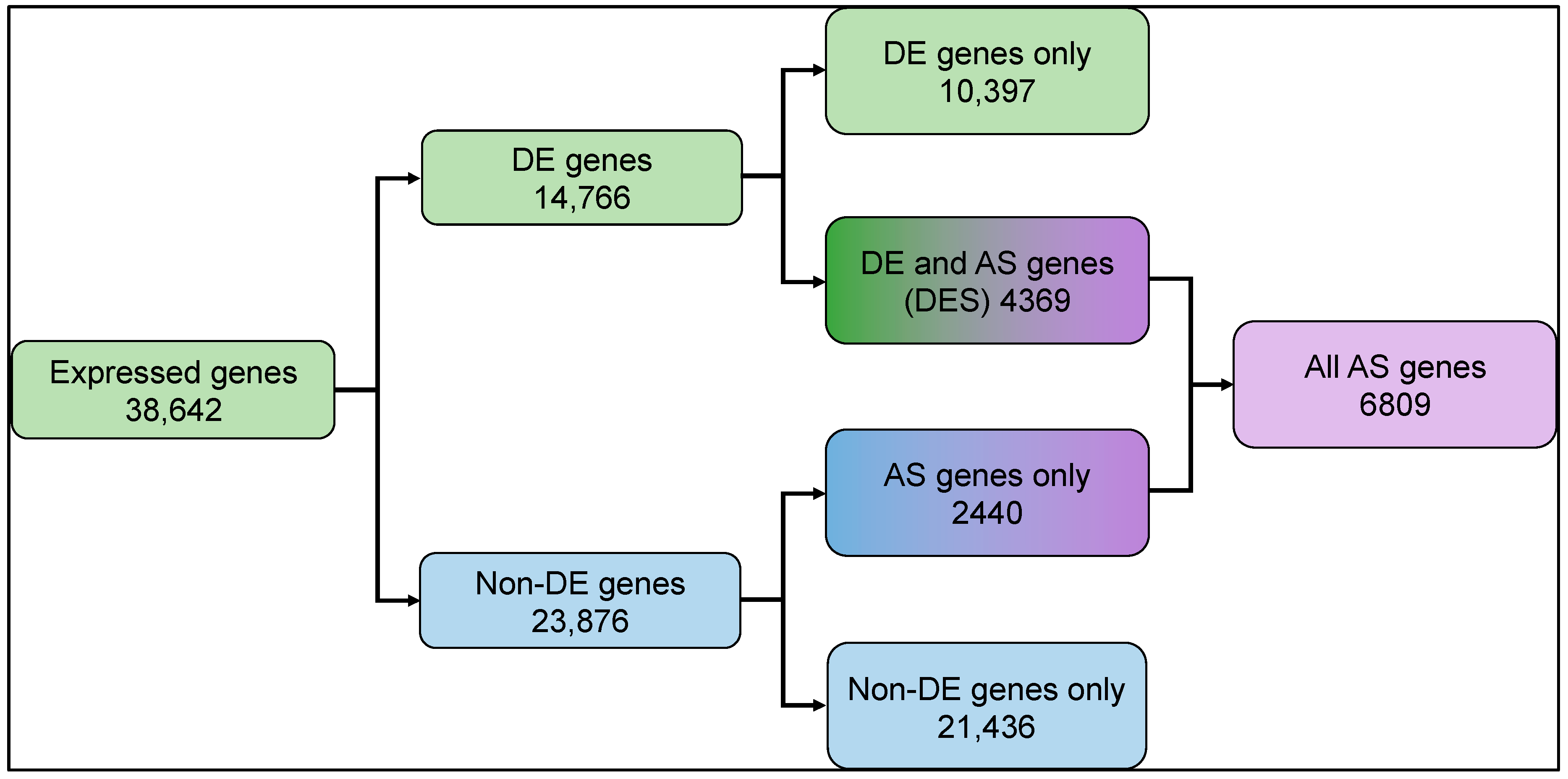

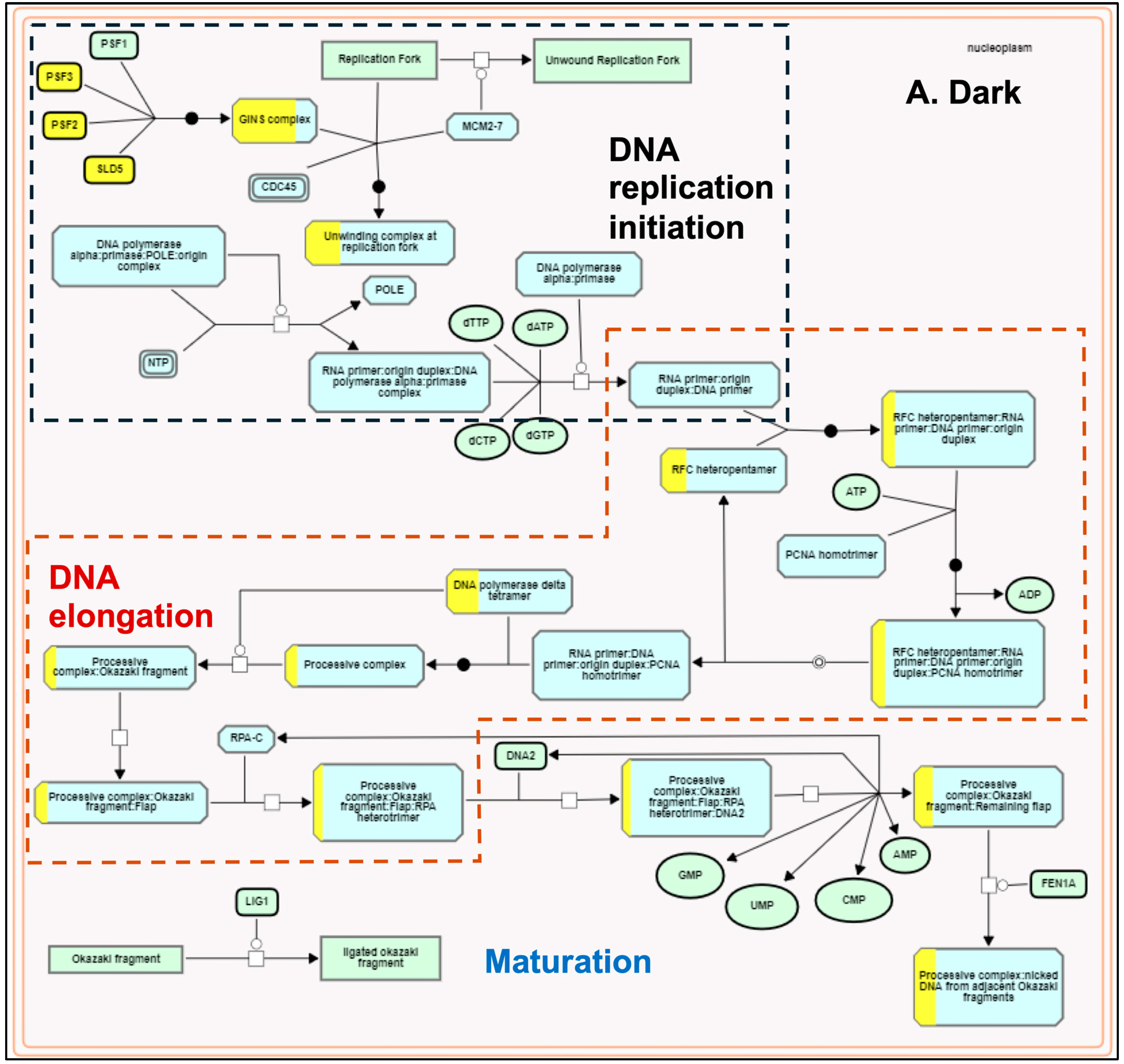

3.1. Light-Mediated Differential Gene Expression during Photomorphogenesis

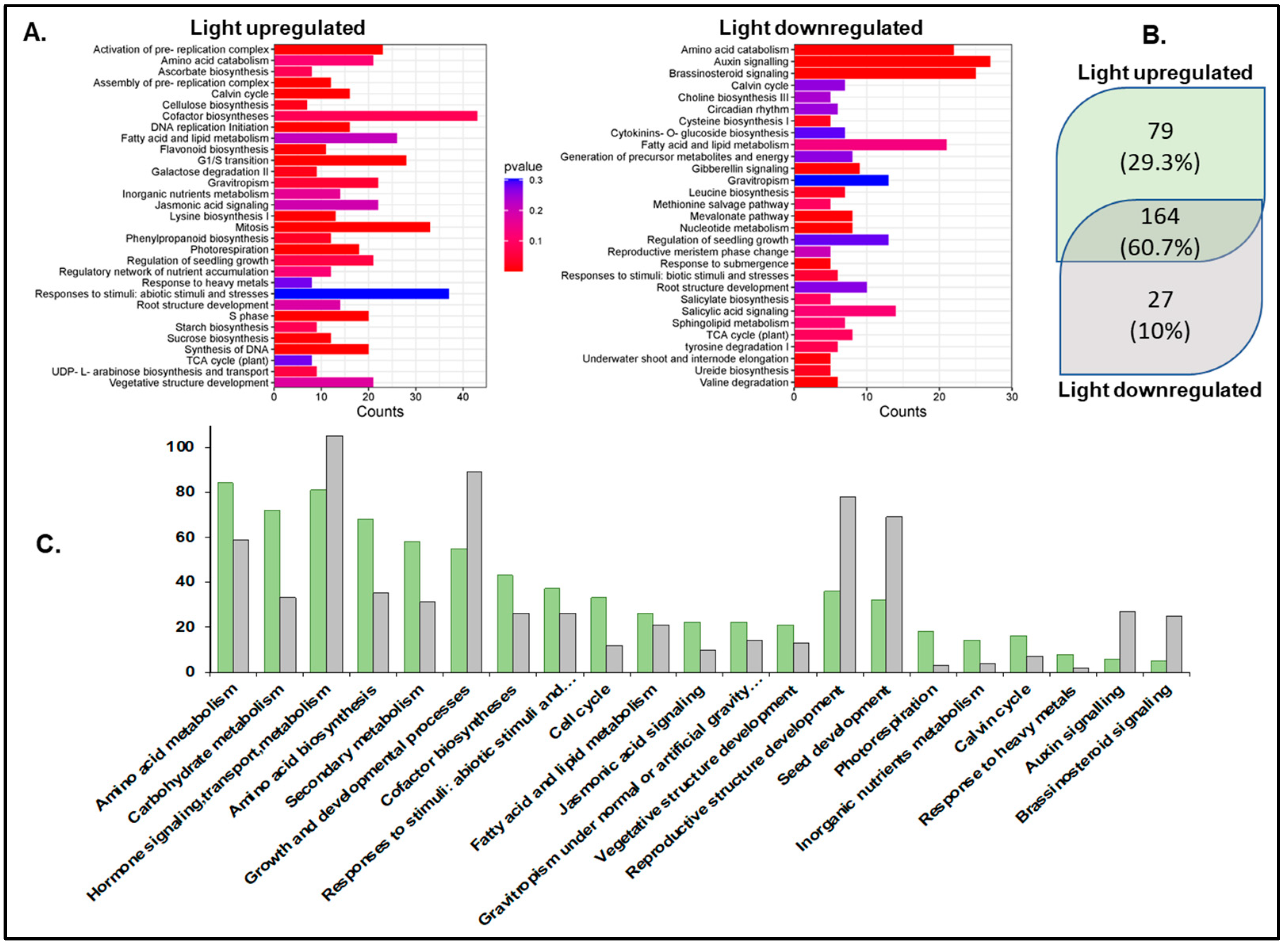

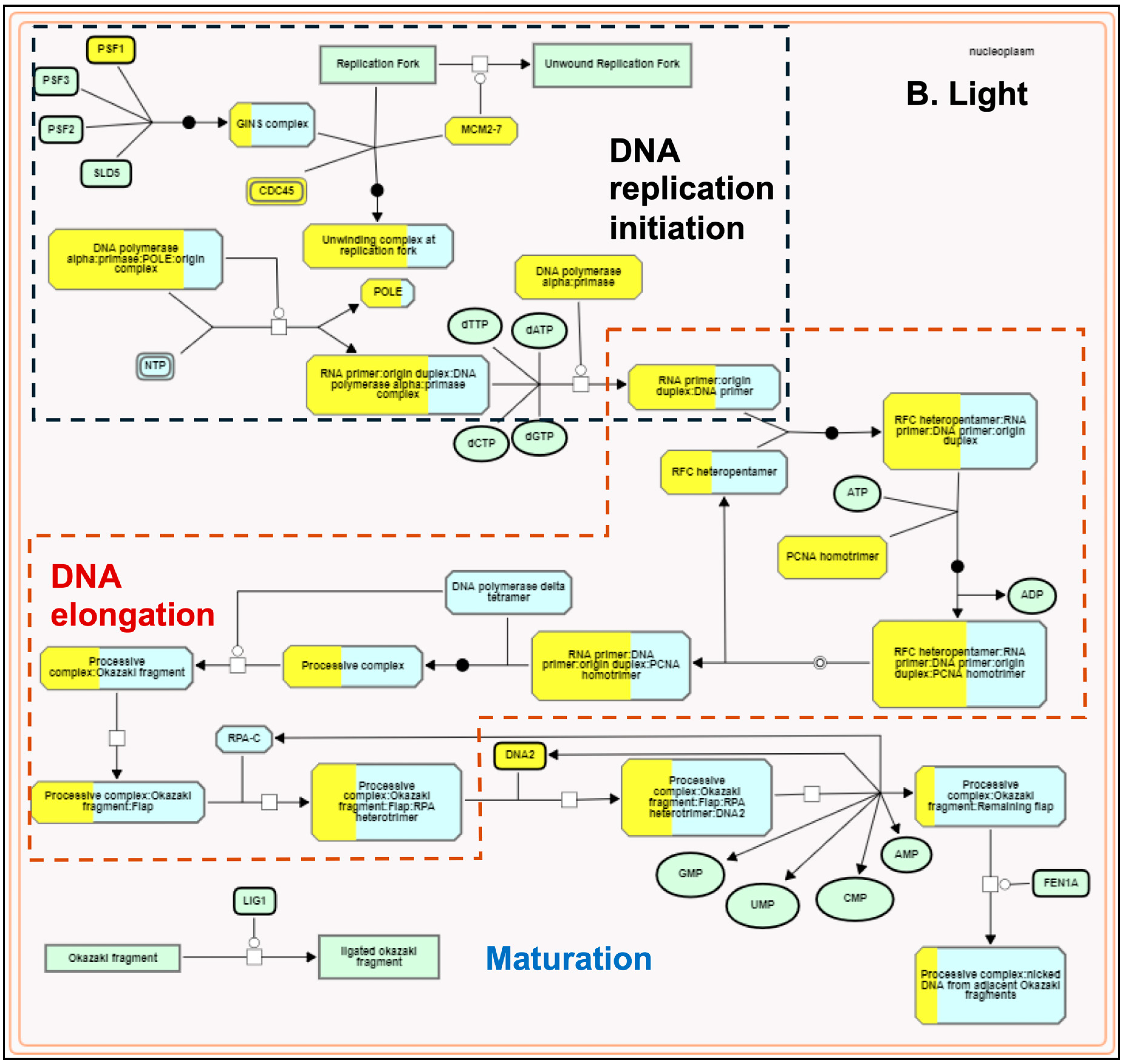

3.2. Gene Function and Pathway Enrichment Analyses

3.3. Identifying Light-Regulated Transcription Factors

3.4. Transcript Splicing during Photomorphogenesis

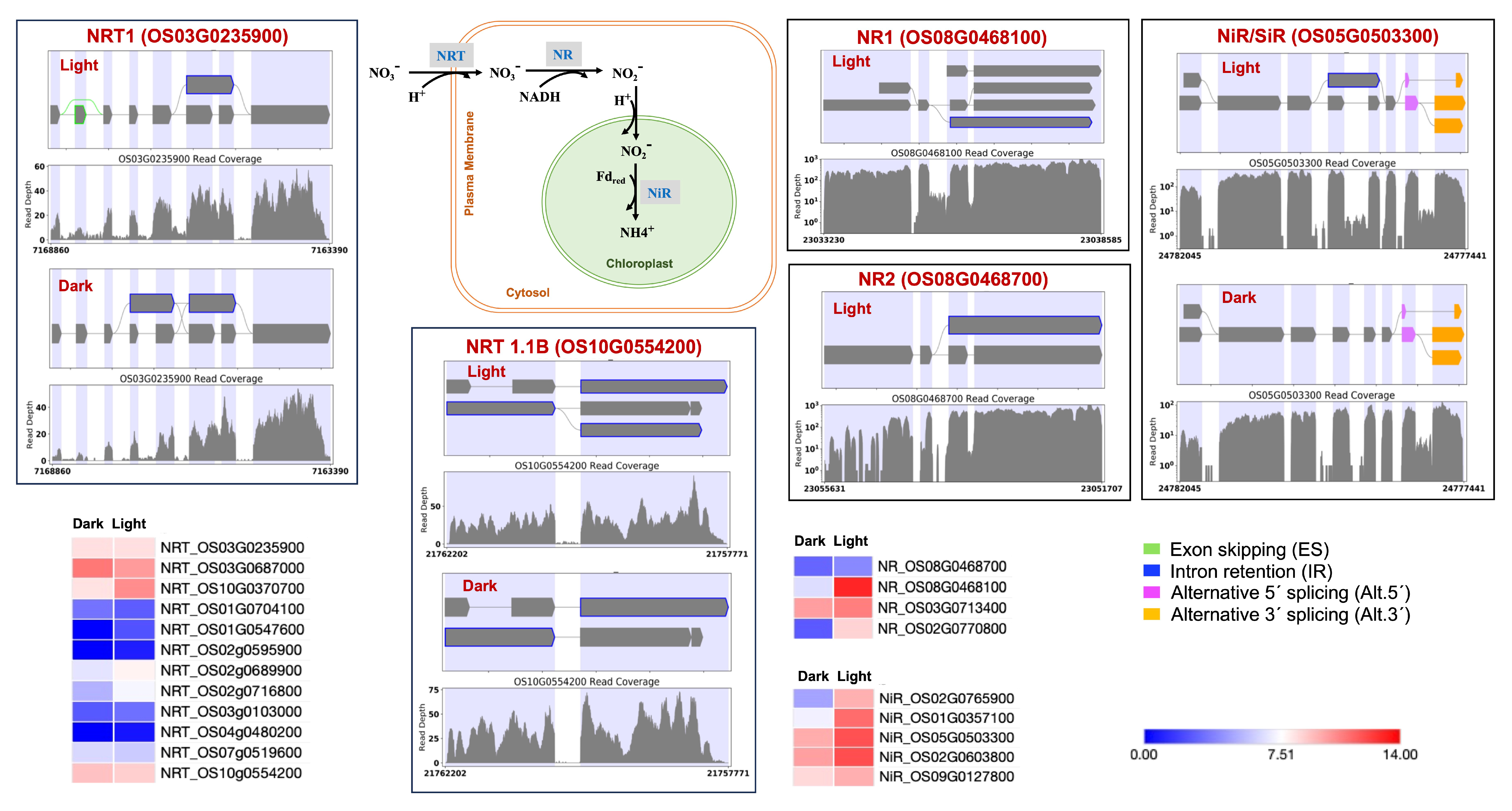

3.5. Light-Mediated Shift in Gene Expression and Splicing Events

3.5.1. Circadian Clock Pathway Genes

3.5.2. MVA and MEP Pathway Genes

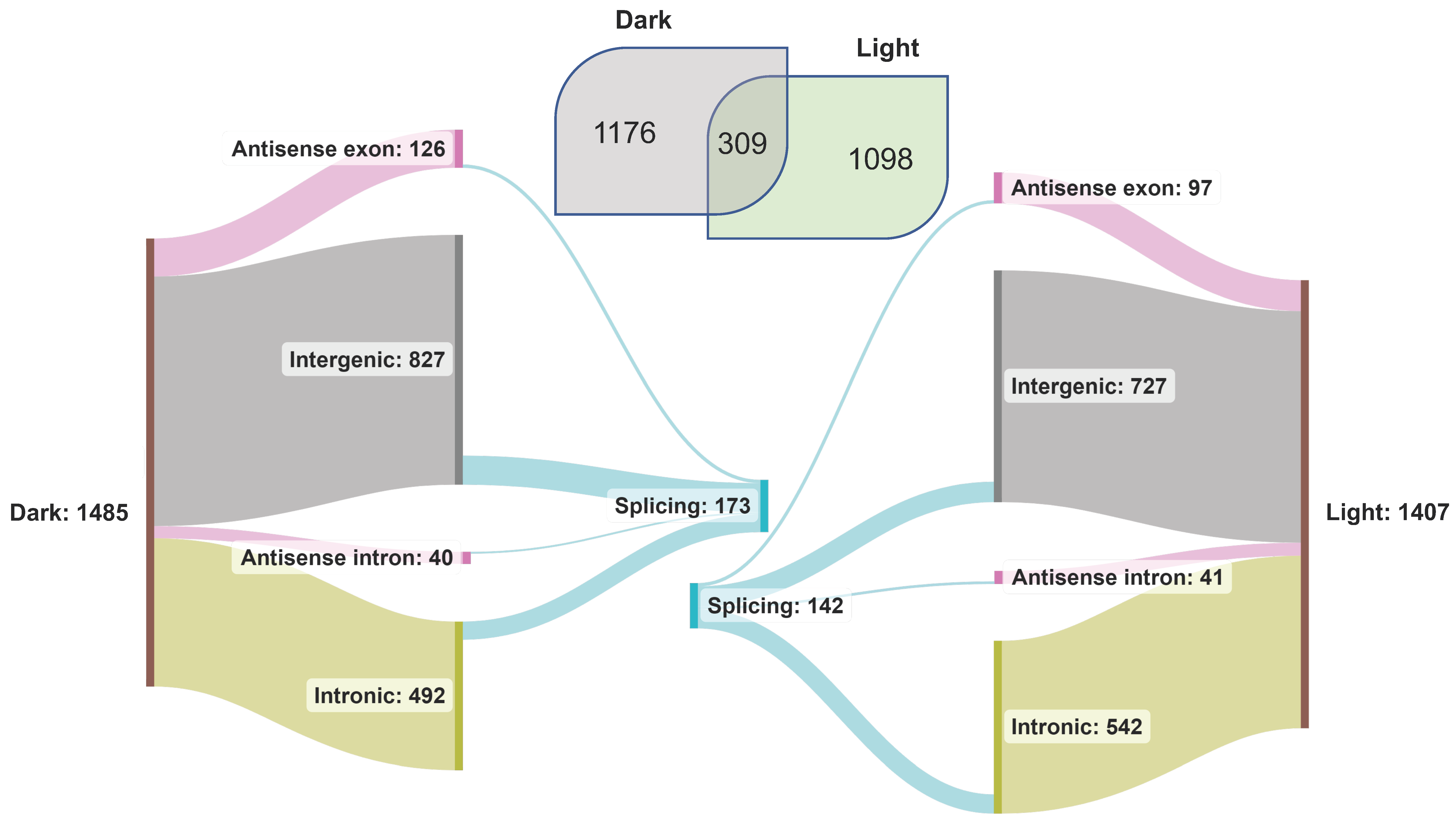

3.6. lncRNA Discovery and Splicing during Photomorphogenesis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kami, C.; Lorrain, S.; Hornitschek, P.; Fankhauser, C. Chapter Two—Light-Regulated Plant Growth and Development. In Current Topics in Developmental Biology; Timmermans, M.C.P., Ed.; Plant Development; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; Volume 91, pp. 29–66. [Google Scholar]

- Poolman, M.G.; Kundu, S.; Shaw, R.; Fell, D.A. Responses to Light Intensity in a Genome-Scale Model of Rice Metabolism. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naithani, S.; Nonogaki, H.; Jaiswal, P. Exploring Crossroads Between Seed Development and Stress Response. In Mechanism of Plant Hormone Signaling under Stress; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 415–454. ISBN 978-1-118-88902-2. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Liang, Z.; Ding, G.; Shi, L.; Xu, F.; Cai, H. A Natural Light/Dark Cycle Regulation of Carbon-Nitrogen Metabolism and Gene Expression in Rice Shoots. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobin, E.M.; Silverthorne, J. Light Regulation of Gene Expression in Higher Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 1985, 36, 569–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Li, J.; Qu, L.; Hager, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, H.; Deng, X.W. Light Control of Arabidopsis Development Entails Coordinated Regulation of Genome Expression and Cellular Pathways. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 2589–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casal, J.J.; Yanovsky, M.J. Regulation of Gene Expression by Light. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2004, 49, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Ma, L.; Strickland, E.; Deng, X.W. Conservation and Divergence of Light-Regulated Genome Expression Patterns during Seedling Development in Rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 3239–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majláth, I.; Szalai, G.; Soós, V.; Sebestyén, E.; Balázs, E.; Vanková, R.; Dobrev, P.I.; Tari, I.; Tandori, J.; Janda, T. Effect of Light on the Gene Expression and Hormonal Status of Winter and Spring Wheat Plants during Cold Hardening. Physiol. Plant. 2012, 145, 296–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrillo, E.; Herz, M.A.G.; Barta, A.; Kalyna, M.; Kornblihtt, A.R. Let There Be Light: Regulation of Gene Expression in Plants. RNA Biol. 2014, 11, 1215–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy Herz, M.A.; Kubaczka, M.G.; Brzyżek, G.; Servi, L.; Krzyszton, M.; Simpson, C.; Brown, J.; Swiezewski, S.; Petrillo, E.; Kornblihtt, A.R. Light Regulates Plant Alternative Splicing through the Control of Transcriptional Elongation. Mol. Cell 2019, 73, 1066–1074.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Tao, R.; Tang, Y.; Yin, L.; Ma, Y.; Ni, J.; Yan, X.; Yang, Q.; Wu, Z.; Zeng, Y.; et al. BBX16, a B-Box Protein, Positively Regulates Light-Induced Anthocyanin Accumulation by Activating MYB10 in Red Pear. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1985–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quail, P.H. Phytochrome Photosensory Signalling Networks. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Shalitin, D. Cryptochrome Structure and Signal Transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2003, 54, 469–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ouyang, X.; Deng, X.W. Beyond Repression of Photomorphogenesis: Role Switching of COP/DET/FUS in Light Signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2014, 21, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheerin, D.J.; Menon, C.; zur Oven-Krockhaus, S.; Enderle, B.; Zhu, L.; Johnen, P.; Schleifenbaum, F.; Stierhof, Y.-D.; Huq, E.; Hiltbrunner, A. Light-Activated Phytochrome A and B Interact with Members of the SPA Family to Promote Photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis by Reorganizing the COP1/SPA Complex. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leivar, P.; Monte, E.; Oka, Y.; Liu, T.; Carle, C.; Castillon, A.; Huq, E.; Quail, P.H. Multiple Phytochrome-Interacting bHLH Transcription Factors Repress Premature Photomorphogenesis during Early Seedling Development in Darkness. Curr. Biol. 2008, 18, 1815–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.; Kim, K.; Kang, H.; Zulfugarov, I.S.; Bae, G.; Lee, C.-H.; Lee, D.; Choi, G. Phytochromes Promote Seedling Light Responses by Inhibiting Four Negatively-Acting Phytochrome-Interacting Factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 7660–7665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Zhang, G.; An, L.; Chen, X.; Fang, R. Phytochrome-Interacting Factor-like Protein OsPIL15 Integrates Light and Gravitropism to Regulate Tiller Angle in Rice. Planta 2019, 250, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.-J.; Wu, S.-H.; Chen, H.-M.; Wu, S.-H. Widespread Translational Control Contributes to the Regulation of Arabidopsis Photomorphogenesis. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2012, 8, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianianmomeni, A. More Light behind Gene Expression. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 488–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.-P.; Su, Y.; Chen, H.-C.; Chen, Y.-R.; Wu, C.-C.; Lin, W.-D.; Tu, S.-L. Genome-Wide Analysis of Light-Regulated Alternative Splicing Mediated by Photoreceptors in Physcomitrella Patens. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, R10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikata, H.; Hanada, K.; Ushijima, T.; Nakashima, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Matsushita, T. Phytochrome Controls Alternative Splicing to Mediate Light Responses in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 18781–18786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, E.; Sanchez, S.E.; Romanowski, A.; Schlaen, R.G.; Sanchez-Lamas, M.; Cerdán, P.D.; Yanovsky, M.J. Acute Effects of Light on Alternative Splicing in Light-Grown Plants. Photochem. Photobiol. 2016, 92, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.-B.; Brendel, V. Genomewide Comparative Analysis of Alternative Splicing in Plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 7175–7180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ner-Gaon, H.; Halachmi, R.; Savaldi-Goldstein, S.; Rubin, E.; Ophir, R.; Fluhr, R. Intron Retention Is a Major Phenomenon in Alternative Splicing in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2004, 39, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filichkin, S.A.; Hamilton, M.; Dharmawardhana, P.D.; Singh, S.K.; Sullivan, C.; Ben-Hur, A.; Reddy, A.S.N.; Jaiswal, P. Abiotic Stresses Modulate Landscape of Poplar Transcriptome via Alternative Splicing, Differential Intron Retention, and Isoform Ratio Switching. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Geniza, M.; Elser, J.; Al-Bader, N.; Baschieri, R.; Phillips, J.L.; Haq, E.; Preece, J.; Naithani, S.; Jaiswal, P. Reference Genome of the Nutrition-Rich Orphan Crop Chia (Salvia Hispanica) and Its Implications for Future Breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1272966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Khokhar, W.; Jabre, I.; Reddy, A.S.N.; Byrne, L.J.; Wilson, C.M.; Syed, N.H. Alternative Splicing and Protein Diversity: Plants Versus Animals. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganie, S.A.; Reddy, A.S.N. Stress-Induced Changes in Alternative Splicing Landscape in Rice: Functional Significance of Splice Isoforms in Stress Tolerance. Biology 2021, 10, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Quilichini, T.D.; Zhai, C.; Qin, L.; Nilsen, K.T.; Li, Q.; Sharpe, A.G.; Kochian, L.V.; Zou, J.; Reddy, A.S.N.; et al. Alternative Splicing Dynamics and Evolutionary Divergence during Embryogenesis in Wheat Species. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1624–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, T.R.; Dinger, M.E.; Mattick, J.S. Long Non-Coding RNAs: Insights into Functions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Chua, N.-H. Long Noncoding RNA Transcriptome of Plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2015, 13, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palos, K.; Yu, L.; Railey, C.E.; Nelson Dittrich, A.C.; Nelson, A.D.L. Linking Discoveries, Mechanisms, and Technologies to Develop a Clearer Perspective on Plant Long Noncoding RNAs. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 1762–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fan, H.; Wang, B.; Yuan, F. Research Progress on the Roles of lncRNAs in Plant Development and Stress Responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1138901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, R.; Mao, B.; Zhao, B.; Wang, J. Identification of lncRNAs Involved in Rice Ovule Development and Female Gametophyte Abortion by Genome-Wide Screening and Functional Analysis. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-C.; Liao, J.-Y.; Li, Z.-Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, J.-P.; Li, Q.-F.; Qu, L.-H.; Shu, W.-S.; Chen, Y.-Q. Genome-Wide Screening and Functional Analysis Identify a Large Number of Long Noncoding RNAs Involved in the Sexual Reproduction of Rice. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Shi, S.; Jiang, N.; Khanzada, H.; Wassan, G.M.; Zhu, C.; Peng, X.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Q.; et al. Genome-Wide Analysis of Long Non-Coding RNAs Affecting Roots Development at an Early Stage in the Rice Response to Cadmium Stress. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.Q.; Jia, Y.L.; Liu, F.Q.; Wang, F.Q.; Fan, F.J.; Wang, J.; Zhu, J.Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhong, W.G.; Yang, J. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of Long Non-Coding RNAs Responsive to Dickeya zeae in Rice. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 34408–34417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Shahid, M.Q.; Wen, M.; Chen, S.; Yu, H.; Jiao, Y.; Lu, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, X. Global Identification and Analysis Revealed Differentially Expressed lncRNAs Associated with Meiosis and Low Fertility in Autotetraploid Rice. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, X.; Lin, F.; He, G.; Terzaghi, W.; Zhu, D.; Deng, X.W. Arabidopsis Noncoding RNA Mediates Control of Photomorphogenesis by Red Light. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 10359–10364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, G.; Márquez, Y.; Mantica, F.; Duque, P.; Irimia, M. Alternative Splicing Landscapes in Arabidopsis Thaliana across Tissues and Stress Conditions Highlight Major Functional Differences with Animals. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Geniza, M.; Naithani, S.; Phillips, J.L.; Haq, E.; Jaiswal, P. Chia (Salvia hispanica) Gene Expression Atlas Elucidates Dynamic Spatio-Temporal Changes Associated with Plant Growth and Development. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 667678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, A.S.N.; Marquez, Y.; Kalyna, M.; Barta, A. Complexity of the Alternative Splicing Landscape in Plants[C][W][OPEN]. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 3657–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.E.; Geniza, M.; Hanumappa, M.; Naithani, S.; Sullivan, C.; Preece, J.; Tiwari, V.K.; Elser, J.; Leonard, J.M.; Sage, A.; et al. De Novo Transcriptome Assembly and Analyses of Gene Expression during Photomorphogenesis in Diploid Wheat Triticum Monococcum. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najoshi Najoshi/Sickle. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/najoshi/sickle (accessed on 16 August 2023).

- Trapnell, C.; Pachter, L.; Salzberg, S.L. TopHat: Discovering Splice Junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1105–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trapnell, C.; Roberts, A.; Goff, L.; Pertea, G.; Kim, D.; Kelley, D.R.; Pimentel, H.; Salzberg, S.L.; Rinn, J.L.; Pachter, L. Differential Gene and Transcript Expression Analysis of RNA-Seq Experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 2012, 7, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C.N. RSEM: Accurate Transcript Quantification from RNA-Seq Data with or without a Reference Genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, N.; Dawson, J.A.; Thomson, J.A.; Ruotti, V.; Rissman, A.I.; Smits, B.M.G.; Haag, J.D.; Gould, M.N.; Stewart, R.M.; Kendziorski, C. EBSeq: An Empirical Bayes Hierarchical Model for Inference in RNA-Seq Experiments. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1035–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Gene Ontology Consortium. The Gene Ontology Resource: 20 Years and Still GOing Strong. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D330–D338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naithani, S.; Preece, J.; D’Eustachio, P.; Gupta, P.; Amarasinghe, V.; Dharmawardhana, P.D.; Wu, G.; Fabregat, A.; Elser, J.L.; Weiser, J.; et al. Plant Reactome: A Resource for Plant Pathways and Comparative Analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D1029–D1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Naithani, S.; Preece, J.; Kim, S.; Cheng, T.; D’Eustachio, P.; Elser, J.; Bolton, E.E.; Jaiswal, P. Plant Reactome and PubChem: The Plant Pathway and (Bio)Chemical Entity Knowledgebases. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2443, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tello-Ruiz, M.K.; Naithani, S.; Gupta, P.; Olson, A.; Wei, S.; Preece, J.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, B.; Chougule, K.; Garg, P.; et al. Gramene 2021: Harnessing the Power of Comparative Genomics and Pathways for Plant Research. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, D1452–D1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, M.F.; Thomas, J.; Reddy, A.S.; Ben-Hur, A. SpliceGrapher: Detecting Patterns of Alternative Splicing from RNA-Seq Data in the Context of Gene Models and EST Data. Genome Biol. 2012, 13, R4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Feng, J.; Jiang, T. IsoLasso: A LASSO Regression Approach to RNA-Seq Based Transcriptome Assembly. J. Comput. Biol. 2011, 18, 1693–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.-J.; Yang, D.-C.; Kong, L.; Hou, M.; Meng, Y.-Q.; Wei, L.; Gao, G. CPC2: A Fast and Accurate Coding Potential Calculator Based on Sequence Intrinsic Features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W12–W16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, P.; Binns, D.; Chang, H.-Y.; Fraser, M.; Li, W.; McAnulla, C.; McWilliam, H.; Maslen, J.; Mitchell, A.; Nuka, G.; et al. InterProScan 5: Genome-Scale Protein Function Classification. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ling, Y.; Xu, W.; Su, Z. PNRD: A Plant Non-Coding RNA Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D982–D989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paytuví Gallart, A.; Hermoso Pulido, A.; Anzar Martínez de Lagrán, I.; Sanseverino, W.; Aiese Cigliano, R. GREENC: A Wiki-Based Database of Plant lncRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D1161–D1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Yang, F.; Xiao, B.; Li, G. RiceLncPedia: A Comprehensive Database of Rice Long Non-coding RNAs. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1492–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofacker, I.L. Vienna RNA Secondary Structure Server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3429–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, A.R.; Lorenz, R.; Bernhart, S.H.; Neuböck, R.; Hofacker, I.L. The Vienna RNA Websuite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, W70–W74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naithani, S.; Gupta, P.; Preece, J.; D’Eustachio, P.; Elser, J.L.; Garg, P.; Dikeman, D.A.; Kiff, J.; Cook, J.; Olson, A.; et al. Plant Reactome: A Knowledgebase and Resource for Comparative Pathway Analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D1093–D1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Elser, J.; Hooks, E.; D’Eustachio, P.; Jaiswal, P.; Naithani, S. Plant Reactome Knowledgebase: Empowering Plant Pathway Exploration and OMICS Data Analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 52, D1538–D1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Tian, F.; Yang, D.-C.; Meng, Y.-Q.; Kong, L.; Luo, J.; Gao, G. PlantTFDB 4.0: Toward a Central Hub for Transcription Factors and Regulatory Interactions in Plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D1040–D1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Guo, L.; Lu, F.; Feng, X.; He, K.; Wei, L.; Chen, Z.; Qu, L.-J.; Gu, H. A Subgroup of MYB Transcription Factor Genes Undergoes Highly Conserved Alternative Splicing in Arabidopsis and Rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiyama, N.; Izawa, T.; Oikawa, T.; Shimamoto, K. Light Regulation of Circadian Clock-Controlled Gene Expression in Rice. Plant J. 2001, 26, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuzaki, J.; Kawahara, Y.; Izawa, T. Punctual Transcriptional Regulation by the Rice Circadian Clock under Fluctuating Field Conditions[OPEN]. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 633–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordoba, E.; Salmi, M.; León, P. Unravelling the Regulatory Mechanisms That Modulate the MEP Pathway in Higher Plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 2933–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vranová, E.; Coman, D.; Gruissem, W. Network Analysis of the MVA and MEP Pathways for Isoprenoid Synthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 665–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranová, E.; Coman, D.; Gruissem, W. Structure and Dynamics of the Isoprenoid Pathway Network. Mol. Plant 2012, 5, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hao, L.; Li, D.; Zhu, L.; Hu, S. Long Non-Coding RNAs and Their Biological Roles in Plants. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2015, 13, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.; Sanz-Jimenez, P.; Zhu, X.-T.; Feng, J.-W.; Shao, L.; Song, J.-M.; Chen, L.-L. Analysis of Rice Transcriptome Reveals the LncRNA/CircRNA Regulation in Tissue Development. Rice 2021, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, T.S.; Figueiredo, D.D.; Cordeiro, A.M.; Almeida, D.M.; Lourenço, T.; Abreu, I.A.; Sebastián, A.; Fernandes, L.; Contreras-Moreira, B.; Oliveira, M.M.; et al. OsRMC, a Negative Regulator of Salt Stress Response in Rice, Is Regulated by Two AP2/ERF Transcription Factors. Plant Mol. Biol. 2013, 82, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argueso, C.T.; Ferreira, F.J.; Kieber, J.J. Environmental Perception Avenues: The Interaction of Cytokinin and Environmental Response Pathways. Plant Cell Environ. 2009, 32, 1147–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthen, J.M.; Yamburenko, M.V.; Lim, J.; Nimchuk, Z.L.; Kieber, J.J.; Schaller, G.E. Type-B Response Regulators of Rice Play Key Roles in Growth, Development and Cytokinin Signaling. Development 2019, 146, dev174870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, A.M.; Figueiredo, D.D.; Tepperman, J.; Borba, A.R.; Lourenço, T.; Abreu, I.A.; Ouwerkerk, P.B.F.; Quail, P.H.; Oliveira, M.M.; Saibo, N.J.M. Rice Phytochrome-Interacting Factor Protein OsPIF14 Represses OsDREB1B Gene Expression through an Extended N-Box and Interacts Preferentially with the Active Form of Phytochrome B. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1859, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Fernie, A.R.; Kang, K.; Panagiotou, G.; Lo, C.; Lim, B.L. Transcriptomic, Proteomic and Metabolic Changes in Arabidopsis Thaliana Leaves after the Onset of Illumination. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Zhao, J.; Pan, T.; Xi, L.; Zhang, J.; Zou, Z. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Gene Expression Patterns in Tomato Under Dynamic Light Conditions. Genes 2019, 10, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Baysal, C.; Drapal, M.; Sheng, Y.; Huang, X.; He, W.; Shi, L.; Capell, T.; Fraser, P.D.; Christou, P.; et al. The Coordinated Upregulated Expression of Genes Involved in MEP, Chlorophyll, Carotenoid and Tocopherol Pathways, Mirrored the Corresponding Metabolite Contents in Rice Leaves during De-Etiolation. Plants 2021, 10, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Grundy, S.; Hardy, K.; Yang, Q.; Lu, C. A Transcriptome Analysis Revealing the New Insight of Green Light on Tomato Plant Growth and Drought Stress Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 649283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Lau, O.S.; Deng, X.W. Light-Regulated Transcriptional Networks in Higher Plants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007, 8, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Wit, M.; Galvão, V.C.; Fankhauser, C. Light-Mediated Hormonal Regulation of Plant Growth and Development. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2016, 67, 513–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, W.N. The Non-Mevalonate Pathway of Isoprenoid Precursor Biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 21573–21577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Agarwal, A.V.; Akhtar, N.; Sangwan, R.S.; Singh, S.P.; Trivedi, P.K. Cloning and Characterization of 2-C-Methyl-d-Erythritol-4-Phosphate Pathway Genes for Isoprenoid Biosynthesis from Indian Ginseng, Withania somnifera. Protoplasma 2013, 250, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulido, P.; Perello, C.; Rodriguez-Concepcion, M. New Insights into Plant Isoprenoid Metabolism. Mol. Plant 2012, 5, 964–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, N.; Suzuki, M.; Yoshida, S.; Muranaka, T. Mevalonic Acid Partially Restores Chloroplast and Etioplast Development in Arabidopsis Lacking the Non-Mevalonate Pathway. Planta 2002, 216, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Concepción, M. Early Steps in Isoprenoid Biosynthesis: Multilevel Regulation of the Supply of Common Precursors in Plant Cells. Phytochem. Rev. 2006, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemian, M.; Lutes, J.; Tepperman, J.M.; Chang, H.-S.; Zhu, T.; Wang, X.; Quail, P.H.; Markus Lange, B. Integrative Analysis of Transcript and Metabolite Profiling Data Sets to Evaluate the Regulation of Biochemical Pathways during Photomorphogenesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2006, 448, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filichkin, S.A.; Priest, H.D.; Givan, S.A.; Shen, R.; Bryant, D.W.; Fox, S.E.; Wong, W.-K.; Mockler, T.C. Genome-Wide Mapping of Alternative Splicing in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung-Uceda, J.; Lee, K.; Seo, P.J.; Polyn, S.; Veylder, L.D.; Mas, P. The Circadian Clock Sets the Time of DNA Replication Licensing to Regulate Growth in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell 2018, 45, 101–113.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Ponnala, L.; Gandotra, N.; Wang, L.; Si, Y.; Tausta, S.L.; Kebrom, T.H.; Provart, N.; Patel, R.; Myers, C.R.; et al. The Developmental Dynamics of the Maize Leaf Transcriptome. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Fang, C.; Wu, M.; Ma, Y.; Liu, T.; Kong, L.-A.; Peng, D.-L.; et al. Global Dissection of Alternative Splicing in Paleopolyploid Soybean. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 996–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.A.; Haas, B.J.; Hamilton, J.P.; Mount, S.M.; Buell, C.R. Comprehensive Analysis of Alternative Splicing in Rice and Comparative Analyses with Arabidopsis. BMC Genom. 2006, 7, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csorba, T.; Questa, J.I.; Sun, Q.; Dean, C. Antisense COOLAIR Mediates the Coordinated Switching of Chromatin States at FLC during Vernalization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 16160–16165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Liu, S.; Nie, X.; Weining, S.; Wu, L. Conservation Analysis of Long Non-Coding RNAs in Plants. Sci. China Life Sci. 2018, 61, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Jung, C.; Xu, J.; Wang, H.; Deng, S.; Bernad, L.; Arenas-Huertero, C.; Chua, N.-H. Genome-Wide Analysis Uncovers Regulation of Long Intergenic Noncoding RNAs in Arabidopsis[C][W]. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 4333–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corona-Gomez, J.A.; Garcia-Lopez, I.J.; Stadler, P.F.; Fernandez-Valverde, S.L. Splicing Conservation Signals in Plant Long Non-Coding RNAs. RNA 2020, 26, 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komiya, R.; Ohyanagi, H.; Niihama, M.; Watanabe, T.; Nakano, M.; Kurata, N.; Nonomura, K.-I. Rice Germline-Specific Argonaute MEL1 Protein Binds to phasiRNAs Generated from More than 700 lincRNAs. Plant J. 2014, 78, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavarenne, J.; Gonin, M.; Champion, A.; Javelle, M.; Adam, H.; Rouster, J.; Conejéro, G.; Lartaud, M.; Verdeil, J.-L.; Laplaze, L.; et al. Transcriptome Profiling of Laser-Captured Crown Root Primordia Reveals New Pathways Activated during Early Stages of Crown Root Formation in Rice. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, H.; Hamera, S.; Chen, X.; Fang, R. miR444a Has Multiple Functions in the Rice Nitrate-Signaling Pathway. Plant J. 2014, 78, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Xu, N.; Wu, Q.; Yu, B.; Chu, Y.; Li, X.; Huang, J.; Jin, L. OsMADS27 Regulates the Root Development in a NO3−—Dependent Manner and Modulates the Salt Tolerance in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Sci. 2018, 277, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pachamuthu, K.; Hari Sundar, V.; Narjala, A.; Singh, R.R.; Das, S.; Avik Pal, H.C.Y.; Shivaprasad, P.V. Nitrate-Dependent Regulation of miR444-OsMADS27 Signalling Cascade Controls Root Development in Rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 3511–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, R.R.; Jangam, A.P.; Malik, A.; Sharma, N.; Jaiswal, D.K.; Raghuram, N. Transcriptomic and Network Analyses Reveal Distinct Nitrate Responses in Light and Dark in Rice Leaves (Oryza sativa Indica Var. Panvel1). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneyama, T.; Suzuki, A. Light-Independent Nitrogen Assimilation in Plant Leaves: Nitrate Incorporation into Glutamine, Glutamate, Aspartate, and Asparagine Traced by 15N. Plants 2020, 9, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geniza, M.; Fox, S.E.; Sage, A.; Ansariola, M.; Megraw, M.; Jaiswal, P. Comparative Analysis of Salinity Response Transcriptomes in Salt-Tolerant Pokkali and Susceptible IR29 Rice. bioRxiv 2023. 2023.08.20.551368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bader, N.; Meier, A.; Geniza, M.; Gongora, Y.S.; Oard, J.; Jaiswal, P. Loss of a Premature Stop Codon in the Rice Wall-Associated Kinase 91 (WAK91) Gene Is a Candidate for Improving Leaf Sheath Blight Disease Resistance. Genes 2023, 14, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naithani, S.; Deng, C.H.; Sahu, S.K.; Jaiswal, P. Exploring Pan-Genomes of Crops: Genomic Resources and Tools for Unraveling Gene Evolution, Function, and Adaptation. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, L.; Drewe-Boß, P.; Wießner, T.; Wagner, G.; Geue, S.; Lee, H.-C.; Obermüller, D.M.; Kahles, A.; Behr, J.; Sinz, F.H.; et al. Alternative Splicing Substantially Diversifies the Transcriptome during Early Photomorphogenesis and Correlates with the Energy Availability in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 2715–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Jaiswal, P. Light-Regulated Gene Expression and Alternative Splicing Data from Rice Seedlings. [CrossRef]

| Members of light-regulated transcription factor gene families | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene family | Upregulated | Downregulated | Gene family | Upregulated | Downregulated |

| ABI3VP1 | 6 | 4 | GRF | 1 | 2 |

| Alfin-like | 1 | 4 | HB | 21 | 24 |

| AP2-EREBP | 23 | 32 | HSF | 3 | 10 |

| ARF | 8 | 8 | LIM | 2 | 1 |

| ARR-B | 1 | 4 | LOB | 2 | 1 |

| BBR-BPC | 0 | 1 | MADS | 6 | 5 |

| BES1 | 0 | 3 | mTERF | 9 | 4 |

| bHLH | 19 | 27 | MYB | 28 | 14 |

| BSD | 1 | 6 | MYB-related | 16 | 25 |

| bZIP | 10 | 27 | NAC | 21 | 19 |

| C2C2-CO-like | 4 | 7 | OFP | 2 | 1 |

| C2C2-Dof | 5 | 4 | Orphans | 20 | 10 |

| C2C2-GATA | 7 | 4 | PBF-2-like | 1 | 0 |

| C2C2-YABBY | 3 | 1 | PLATZ | 1 | 4 |

| C2H2 | 14 | 19 | RWP-RK | 4 | 2 |

| C3H | 16 | 24 | S1Fa-like | 1 | 1 |

| CAMTA | 0 | 3 | SBP | 3 | 5 |

| CCAAT | 9 | 11 | Sigma 70-like | 4 | 0 |

| CPP | 1 | 4 | SRS | 1 | 0 |

| CSD | 0 | 1 | TAZ | 1 | 1 |

| DBP | 2 | 3 | TCP | 4 | 6 |

| E2F/DP | 2 | 1 | Tify | 6 | 2 |

| EIL | 1 | 1 | Trihelix | 3 | 9 |

| FAR1 | 5 | 10 | TUB | 2 | 5 |

| FHA | 7 | 6 | ULT | 1 | 0 |

| G2-like | 9 | 5 | VOZ | 0 | 2 |

| GeBP | 0 | 3 | WRKY | 22 | 10 |

| GRAS | 8 | 7 | zf-HD | 5 | 3 |

| Members of other transcriptional regulator gene families | |||||

| Gene family | Upregulated | Downregulated | Gene family | Upregulated | Downregulated |

| ARID | 2 | 1 | PHD | 12 | 22 |

| AUX/IAA | 3 | 19 | Pseudo ARR-B | 2 | 1 |

| Coactivator p15 | 0 | 1 | RB | 0 | 1 |

| DDT | 3 | 0 | Rcd1-like | 0 | 2 |

| GNAT | 12 | 8 | SET | 11 | 6 |

| HMG | 4 | 5 | SNF2 | 11 | 9 |

| Jumonji | 4 | 5 | SOH1 | 0 | 2 |

| LUG | 0 | 2 | SWI/SNF-BAF60b | 4 | 4 |

| MBF1 | 0 | 1 | SWI/SNF-SWI3 | 2 | 1 |

| MED6 | 0 | 1 | TRAF | 7 | 11 |

| Chromosome # | Treatment | SpliceGrapher Prediction | IsoLasso | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genes | IR | ES | Alt5’ | Alt3’ | Genes | IR | ES | Alt5’ | Alt3’ | ||

| 1 | Dark | 924 | 897 | 214 | 163 | 97 | 939 | 925 | 214 | 181 | 99 |

| Light | 1028 | 994 | 264 | 184 | 109 | 1048 | 1021 | 264 | 191 | 112 | |

| 2 | Dark | 747 | 728 | 224 | 167 | 109 | 771 | 781 | 227 | 189 | 117 |

| Light | 802 | 777 | 219 | 153 | 99 | 822 | 812 | 222 | 165 | 103 | |

| 3 | Dark | 825 | 797 | 216 | 136 | 94 | 858 | 868 | 216 | 162 | 120 |

| Light | 945 | 893 | 219 | 143 | 98 | 960 | 920 | 219 | 153 | 118 | |

| 4 | Dark | 565 | 551 | 182 | 112 | 64 | 581 | 576 | 183 | 117 | 67 |

| Light | 596 | 572 | 193 | 104 | 61 | 611 | 592 | 194 | 109 | 66 | |

| 5 | Dark | 519 | 503 | 139 | 139 | 70 | 538 | 534 | 140 | 114 | 75 |

| Light | 552 | 537 | 144 | 103 | 80 | 562 | 550 | 144 | 109 | 92 | |

| 6 | Dark | 509 | 459 | 186 | 128 | 62 | 527 | 493 | 186 | 135 | 64 |

| Light | 531 | 501 | 169 | 103 | 63 | 554 | 535 | 169 | 109 | 67 | |

| 7 | Dark | 466 | 432 | 166 | 77 | 48 | 482 | 468 | 166 | 85 | 51 |

| Light | 481 | 473 | 129 | 72 | 52 | 498 | 498 | 129 | 82 | 56 | |

| 8 | Dark | 400 | 390 | 97 | 63 | 62 | 415 | 416 | 98 | 68 | 64 |

| Light | 463 | 433 | 134 | 62 | 84 | 475 | 457 | 134 | 67 | 87 | |

| 9 | Dark | 341 | 342 | 79 | 53 | 32 | 349 | 359 | 79 | 64 | 37 |

| Light | 375 | 361 | 118 | 49 | 38 | 382 | 377 | 118 | 53 | 39 | |

| 10 | Dark | 290 | 275 | 94 | 43 | 29 | 295 | 288 | 94 | 49 | 36 |

| Light | 308 | 295 | 102 | 61 | 32 | 314 | 307 | 102 | 65 | 35 | |

| 11 | Dark | 304 | 266 | 113 | 49 | 35 | 313 | 278 | 113 | 53 | 36 |

| Light | 363 | 306 | 150 | 51 | 35 | 374 | 325 | 150 | 57 | 37 | |

| 12 | Dark | 324 | 310 | 117 | 69 | 45 | 329 | 315 | 117 | 74 | 46 |

| Light | 365 | 347 | 150 | 63 | 53 | 372 | 359 | 155 | 68 | 61 | |

| Known Spliced Genes | Spliced in | Light Regulation | Gene Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Os01g0619000 | Dark, Light | Down | RNA recognition motif domain-containing protein |

| Os01g0649900 | Dark, Light | - | GDSL esterase/lipase protein 20 |

| Os01g0764000 | Dark, Light | Up | PHI glutathione s-transferase 2 |

| Os01g0834400 | Dark | - | HAP3A subunit of CCAAT-box binding complex |

| Os02g0122800 | Dark, Light | Down | Similar to Arginine/serine-rich splicing factor |

| Os02g0130600 | Dark | Up | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| Os02g0161900 | Dark, Light | Down | Rice ubiquitin2 |

| Os02g0197900 | Dark, Light | Down | OsSTA53 |

| Os02g0274900 | Dark, Light | Up | Similar to metabolite transport protein CSBC |

| Os02g0577100 | Dark, Light | Down | Zinc finger, RING/PHD-type domain containing protein |

| Os02g0666200 | Light | Down | Aquaporin |

| Os02g0834000 | Dark, Light | Up | Rac-like GTP-binding protein 5 |

| Os02g0291000 | - | Down | Calcineurin B-like protein 7 |

| Os02g0291400 | - | - | Calcineurin B-like protein 8 |

| Os02g0823100 | - | Up | Plasma membrane intrinsic protein 1;3 |

| Os03g0265600 | Dark, Light | Down | Transformer-2-like protein |

| Os03g0314100 | Dark, Light | Down | DEAD-like helicase |

| Os03g0395900 | Dark, Light | Down | Splicing factor |

| Os03g0670700 | Dark, Light | Down | Glycine-rich RNA-binding protein 3 |

| Os03g0698500 | Dark, Light | Down | Similar to Yippee-like protein 3 |

| Os03g0745000 | Dark, Light | - | Heat stress transcription factor A-2a |

| Os03g0717600 | - | Down | Zinc finger, C2H2-type |

| Os04g0115400 | Dark, Light | Down | D111/G-patch domain containing protein |

| Os04g0649100 | Dark, Light | - | Shattering abortion 1 |

| Os04g0656100 | Light | Down | H+-ATPase |

| Os04g0665800 | Dark, Light | Up | Similar to H1005F08.12 protein |

| Os04g0402300 | - | - | Cysteine-type peptidase |

| Os04g0479200 | - | Up | Similar to NAD-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase c;1 |

| Os05g0348100 | Dark | Up | Similar to CRR23 (chlororespiratory reduction 23) |

| Os05g0463800 | Dark, Light | Down | HAP3C subunit of CCAAT-box binding complex |

| Os05g0554400 | Dark, Light | Down | Phosphatidyl serine synthase family protein |

| Os05g0574700 | Dark, Light | - | Similar to cDNA clone:002-182-C01 |

| Os05g0534400 | - | Up | Calcineurin B-like protein 4 |

| Os05g0548900 | - | Up | Phosphoethanolamine N-Methyltransferase 2 |

| Os06g0172800 | Light | - | Similar to alkaline alpha galactosidase 2 |

| Os06g0651600 | Dark, Light | Down | Protein phosphatase 2C58 |

| Os06g0727200 | Dark | Down | Catalase B |

| Os06g0128500 | - | Up | Ribosomal protein L47, mitochondrial family protein |

| Os06g0133000 | - | - | Glutinous endosperm, waxy |

| Os06g0506600 | - | - | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme 17 |

| Os07g0490400 | Dark, Light | Up | FK506 binding protein 20-2 |

| Os07g0574800 | - | Up | Tubulin alpha-1 chain |

| Os07g0613300 | - | - | Similar to PAUSED |

| Os08g0191600 | Dark, Light | Up | Autophagy associated gene 8C |

| Os08g0530400 | Dark, Light | Up | Moco containing protein, similar to sulfite oxidase |

| Os08g0436200 | - | - | Zinc finger, RING/PHD-type domain containing protein |

| Os10g0115600 | Dark, Light | Down | U1 snRNP 70K |

| Os10g0535800 | Dark, Light | - | Cys-rich domain containing protein |

| Os10g0564900 | Dark | Down | Similar to protein kinase CK2 regulatory subunit CK2B2 |

| Os10g0567400 | Dark, Light | Up | Chlorophyll a oxygenase 1 |

| Os10g0577900 | Dark, Light | - | Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase |

| Os10g0411500 | - | Down | Q calmodulin-binding region domain containing protein |

| Os11g0157100 | Dark, Light | Down | Cyclin-T1-4 |

| Os11g0700500 | Dark | - | MybAS1 |

| Os11g0600700 | - | Up | Zinc finger, RING domain protein |

| Os12g0567300 | Dark | Up | MybAS2, R2R3-Myb |

| Os12g0632000 | Dark, Light | Down | Glycine-rich Protein GRP162 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gupta, P.; Jaiswal, P. Transcriptional Modulation during Photomorphogenesis in Rice Seedlings. Genes 2024, 15, 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes15081072

Gupta P, Jaiswal P. Transcriptional Modulation during Photomorphogenesis in Rice Seedlings. Genes. 2024; 15(8):1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes15081072

Chicago/Turabian StyleGupta, Parul, and Pankaj Jaiswal. 2024. "Transcriptional Modulation during Photomorphogenesis in Rice Seedlings" Genes 15, no. 8: 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes15081072