Experimental Development of Transport Percussion Marks on Obsidian Clasts, Pilauco Site, Chilean Northwestern Patagonia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting

3. Materials and Methods

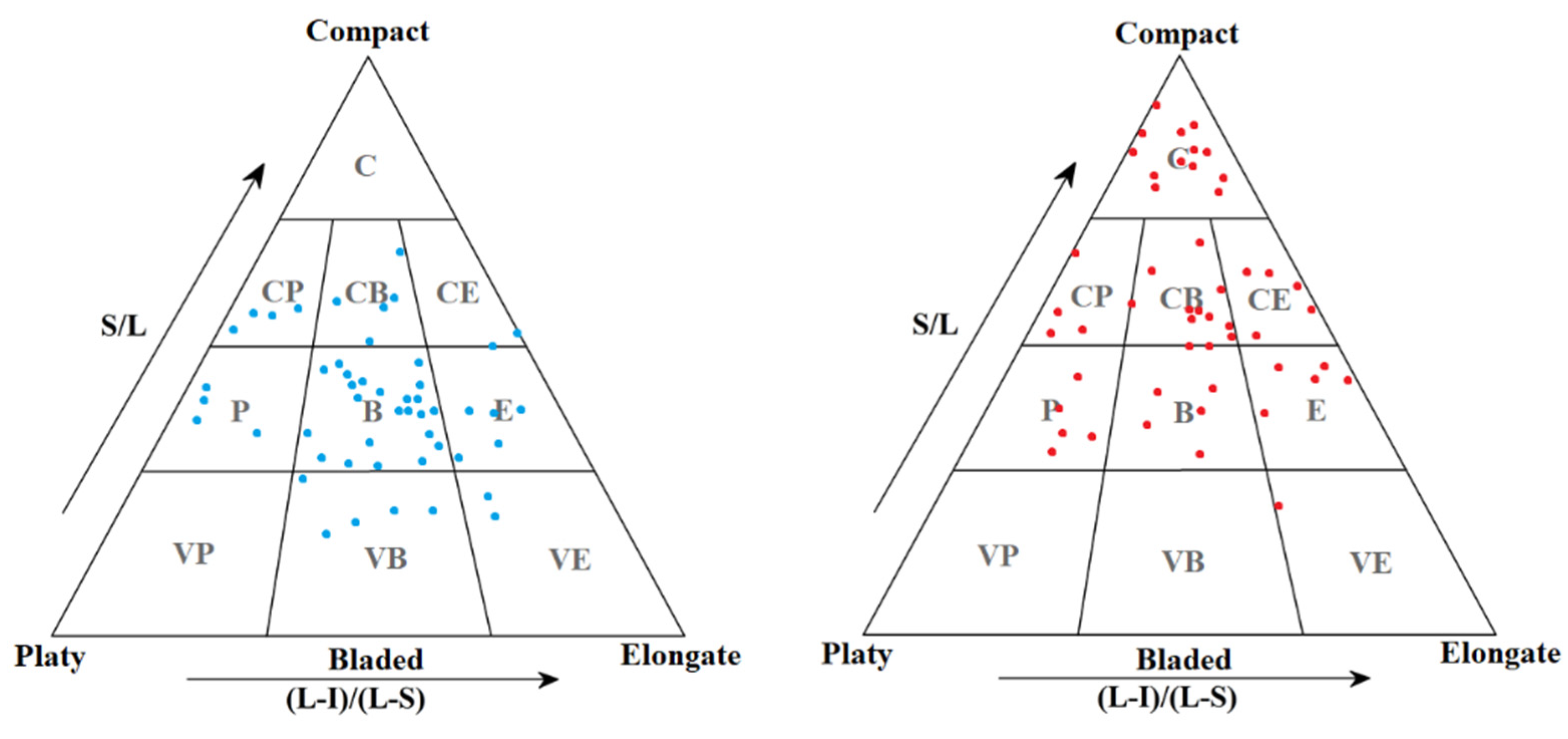

4. Results

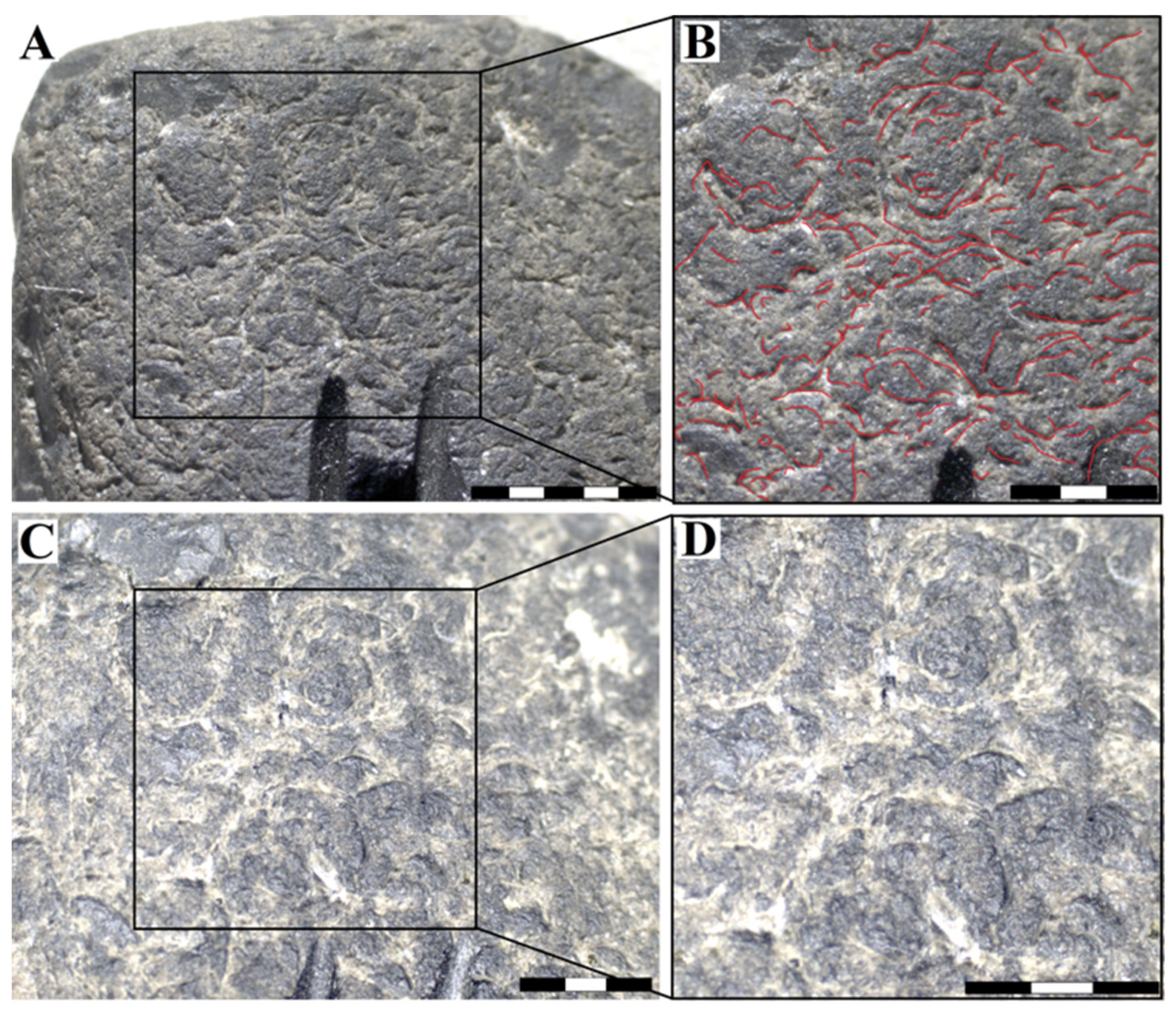

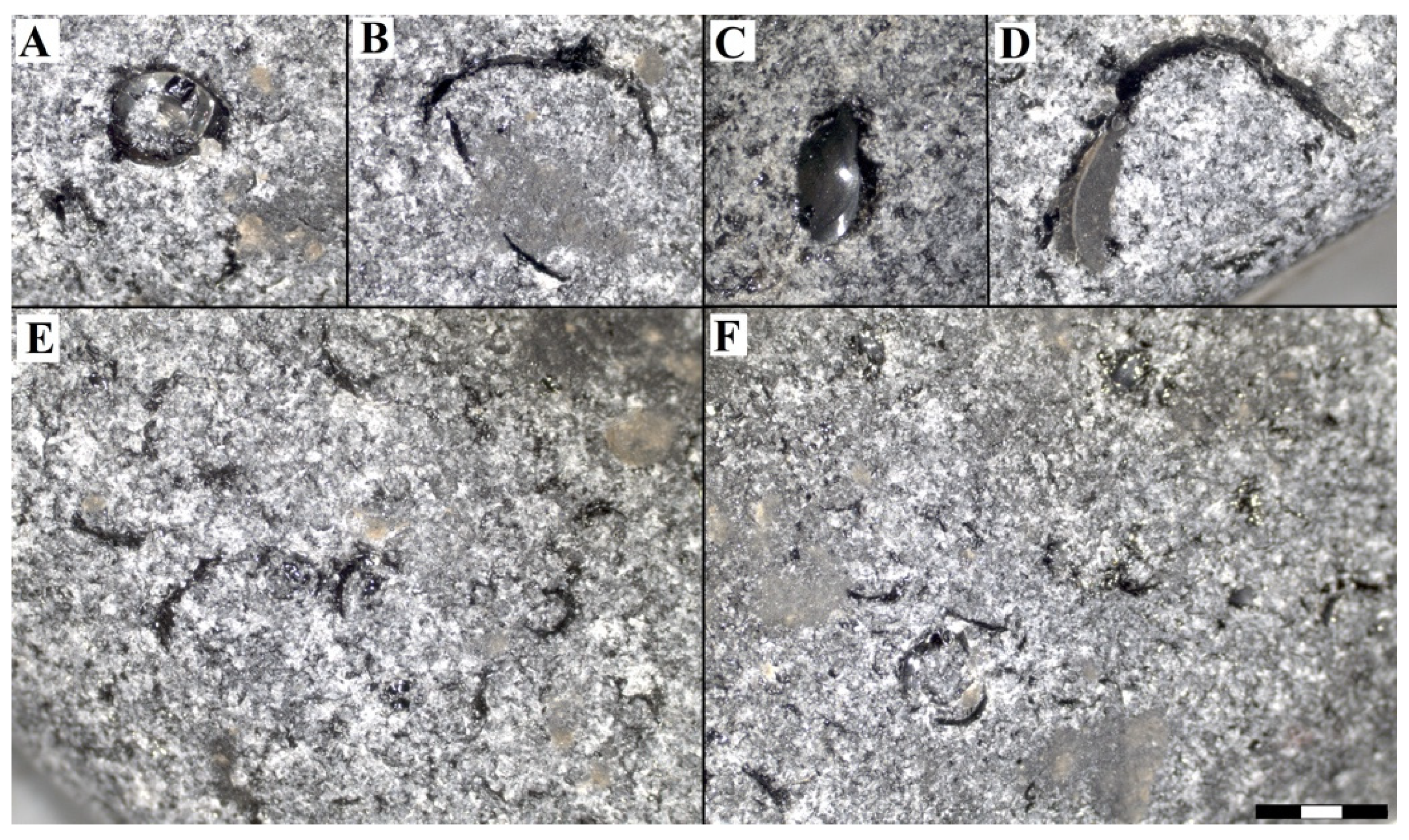

- Crescent marks: They are characterized by having a crescent or half-moon shape, generally having clean edges and a vitreous luster characteristic of a conchoidal fracture. In the cobbles and pebbles without manipulation, they concentrate in a greater density on the edges and faces with greater exposure. In the natural clasts, these marks measured from 2 to 9 mm long and had a density of up to 70 marks cm−2. In the broken clast ensemble, the length was between 2 and 6 mm, also accumulating in greater quantity on the edges and freshly fractured faces (with greater exposure to collisions between clasts). They have a similar density of up to 65 marks cm−2 (Figure 7 and Figure 8).

- Circular marks: They correspond to a complete circle, easily distinguishable by their well-marked edges. They also have a vitreous luster characteristic of conchoidal fractures and stand out for the thickness of the edges, which are generally thicker than the crescent marks. Occasionally, two crescent marks may join to form a circular mark. Both in the natural and broken clasts, the length varies between 3 and 5 mm, and they have a low density comprising up to 5 marks cm–2 (Figure 7 and Figure 8).

- Pseudo-circular marks: The marks classified in this type are not perfectly circular in shape, with poorly defined edges, and in some cases are irregular. Most of them correspond to imperfect shapes with open ends, so in some cases they may resemble crescent marks. In the non-modified cobbles and pebbles, the length fluctuates between 2 and 8 mm, though these are very uncommon. In the broken clasts, these marks are between 2 and 15 mm long and can be observed associated with concave fractures, with well-marked circular edges and others with more irregular edges following a semi-circular shape (Figure 7 and Figure 8). In addition, in this case, from 3 and up to 5 marks cm−2 were observed in the natural and broken sets, respectively.

- Irregular marks: These marks do not follow a common pattern, nor do they have similar sizes, since they can range from millimetric to centimetric sizes. They are marks generated in thinner, weaker edges and therefore with a greater tendency to fracture. In the natural cobbles and pebbles, these marks do not follow a pattern and can be the largest, with lengths ranging from 2 to 14 mm. In the broken obsidian pieces, the length can vary from 1 to 12 mm (Figure 7 and Figure 8). The concentration comprises up to 30 marks cm−2.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, D.G. Documenting early lithic technologies in South America. Chungara 2015, 47, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillehay, T.D. Entangled knowledge: Old trends and new thoughts in first South American studies. In Paleoamerican Odyssey; Graf, K.E., Ketron, C.V., Waters, M.R., Eds.; Texas A&M University Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2014; pp. 377–396. ISBN 978-1-62349-192-5. [Google Scholar]

- Aceituno, F.J.; Loaiza, N.; Delgado-Burbano, M.E.; Barrientos, G. The initial human settlement of Northwest South America during the Pleistocene/Holocene transition: Synthesis and perspectives. Quat. Int. 2013, 301, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, G.A.; Mancini, M.V.; Franco, N.V.; Bamonte, F.; Ambrústolo, P. An examination of possible relationships between paleoenvironmental conditions during the Pleistocene/Holocene transition and human occupation of southern Patagonia (Argentina) east of the Andes, between 46° and 52° S. Quat. Int. 2013, 305, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillehay, T.D. Monte Verde: A late Pleistocene Settlement in Chile. In Paleoenvironmental and Site Context; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillehay, T.D. Monte Verde, a late Pleistocene Settlement in Chile. In The Archaeological Context and Interpretation; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, M.; Astorga, G. Pilauco: A Late Pleistocene Archaeo-Paleontological Site. Osorno, Northwestern Patagonia and Chile; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, K.; Bostelmann, E.; Macías, C.; Navarro-Harris, X.; De Pol-Holz, R.; Pino, M. A late Pleistocene human footprint from the Pilauco archaeological site, Northern Patagonia, Chile. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Harris, X.; Pino, M.; Guzmán-Marín, P.; Lira, M.P.; Labarca, R.; Corgne, A. The procurement and use of knappable glassy volcanic raw material, Upper Pleistocene Pilauco site, Chilean Northwestern Patagonia. Geoarchaeology 2019, 34, 592–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, M.; Chavez, M.; Navarro-Harris, X.; Labarca, R. The Late Pleistocene Pilauco Site, South Central Chile. Quat. Int. 2013, 299, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, M.; Martel-Cea, A.; Vega, R.M.; Fritte, D.; Soto-Bollmann, K. Geology, Stratigraphy, and Chronology of the Pilauco Site. In Pilauco: A Late Pleistocene Archaeo-Paleontological Site. Osorno, Northwestern Patagonia and Chile; Pino, M., Astorga, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 33–54. ISBN 978-3-030-23917-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; Navarro-Harris, X.; Boëda, E.; Pino, M. Beyond the mighty projectile point: Techno-functional study in a late Pleistocene artifact, Pilauco site, Osorno, northwestern Chilean Patagonia. Lithic Technol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrero, L.; Franco, N.V. Early Patagonian Hunter-Gatherers: Subsistence and Technology. J. Anthropol. Res. 1997, 53, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, A.; Gruhn, R. Some difficulties in modeling the original peopling of the Americas. Quat. Int. 2003, 109–110, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, C.A.; Jackson, D. Terminal Pleistocene lithic technology and use of space in Central Chile. Chungará 2015, 47, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Giesso, M.; Berón, M.; Glascock, M. Obsidian in Western Pampas, Argentina: Source characterization and provisioning strategies. APS Bull. 2008, 38, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Seelenfreund, A.; Fonseca, E.; Llona, F.; Lera, L.L.; Sinclaire, C.; Rees, C. Geochemical analysis of vitreous rocks exploited during the Formative period in the Atacama Region, northern Chile. Archaeometry 2009, 51, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, C.R. Obsidian sources and distribution in Patagonia, southernmost South America. Quat. Int. 2018, 468, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillehay, T.D. The Settlement of the Americas: A New Prehistory; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Harris, X.; Pino, M.; Guzman-Marín, P. The Cultural Materials from Pilauco and Los Notros Sites. In Pilauco: A Late Pleistocene Archaeo-Paleontological Site: Osorno, Northwestern Patagonia and Chile; Pino, M., Astorga, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 271–316. ISBN 978-3-030-23917-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrero, L.A. Con lo mínimo: Los debates sobre el poblamiento de América del Sur. Intersecc. Antropol. 2015, 16, 5–38. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, B.J. Obsidian source characterization and hunter–gatherer mobility: An example from the Tucson Basin. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2000, 27, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, C.R.; Caracotche, S.; Cruz, I.; Charlin, J. Obsidiana gris porfírica calco-alcalina del volcán Chaitén en sitios arqueológicos al sur del río Santa Cruz, Patagonoa Meridional. Magallania 2012, 40, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, C.R.; García, C.; Navarro-Harris, X.; Muñoz, J. Sources distribution of different types of obsidian from archaeological sites in central-south Chile (38–44° S). Magallania 2009, 37, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stern, C.R.; Navarro-Harris, X.; Muñoz, J. Obsidiana gris translúcida del volcán Chaitén en los sitios arqueológicos de Quilo (Isla Grande Chiloé) y Chanchán (X Región), Chile, y obsidiana del Mioceno en Chiloé. An. Inst. Patagon. 2002, 30, 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, C.R.; Navarro-Harris, X.; Pino, J.; Vega, R. Nueva fuente de obsidiana en la región de La Araucanía, centro sur de Chile: Química y contexto arqueológico de la obsidiana riolítica negra de los Nevados del Sollipulli. Magallania 2008, 36, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vos, K.; Vandenberghe, N.; Elsen, J. Surface textural analysis of quartz grains by scanning electron microscopy (SEM): From sample preparation to environmental interpretation. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2014, 128, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folk, R. Petrology of Sedimentary Rocks; Hemphill Pub.: Austin, TX, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Wasson, R.J.; Sundriyal, Y.P.; Chaudhary, S.; Jaiswal, M.K.; Morthekai, P.; Sati, S.P.; Juyal, N. A 1000-year history of large floods in the Upper Ganga catchment, central Himalaya, India. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2013, 77, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries Klein, G. Boulder Surface Markings in Quaco Formation (Upper Triassic), St. Martin’s, New Brunswick, Canada. J. Sediment. Res. 1963, 33, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krinsley, D.; Donahue, J. Pebble surface textures. Geol. Mag. 1968, 105, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, R.D.; Bentley, M.J.; Purves, R.S.; Hulton, N.R.; Sugden, D.E.; Clapperton, C.M. Climatic inferences from glacial and paleoecological evidence at the last glacial termination, southern South America. J. Quat. Sci. 2000, 15, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, S.; Charlet, F.; Charlier, B.; Renson, V.; Fagel, N. Climate variability of southern Chile since the Last Glacial Maximum: A continuous sedimentological record from Lago Puyehue (40°S). J. Paleolimnol. 2008, 39, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlet, F.; De Batist, M.; Chapron, E.; Bertrand, S.; Pino, M.; Urrutia, R. Seismic stratigraphy of Lago Puyehue (Chilean Lake District): New views on its deglacial and Holocene evolution. J. Paleolimnol. 2008, 39, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterken, M.; Verleyen, E.; Sabbe, K.; Terryn, G.; Charlet, F.; Bertrand, S.; Vyverman, W. Late Quaternary climatic changes in southern Chile, as recorded in a diatom sequence of Lago Puyehue (40 40′ S). J. Paleolimnol. 2008, 39, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.N.; Vellanoweth, R.L.; Sholts, S.B.; Wärmländer, S.K. Residue analysis, use-wear patterns, and replicative studies indicate that sandstone tools were used as reamers when producing shell fishhooks on San Nicolas Island, California. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2018, 20, 502–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, S.P.; St-Pierre, C.G.; Lominy, M.; Lessa, A. Shark teeth used as tools: An experimental archaeology study. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2021, 35, 102733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RufàBonache, A.; Alonso, G.; Blasco, R.; Cueto, M.; Camarós, E. Testing the damage caused by a golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) on a primate skull: A taphonomic case study of the bone damage observed after a simulated predatory attack. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2020, 30, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudelić, A. Scientific-educational and popular program: Prehistoric pottery: Interdisciplinarity and experiment. Ann. Inst. Archaeol. 2019, 15, 233–238. [Google Scholar]

- Starkovich, B.M.; Cuthbertson, P.; Kitagawa, K.; Thompson, N.; Konidaris, G.E.; Rots, V.; Münzel, S.C.; Giusti, D.; Schmid, V.C.; Blanco-Lapaz, A.; et al. Minimal Tools, Maximum Meat: A Pilot Experiment to Butcher an Elephant Foot and Make Elephant Bone Tools Using Lower Paleolithic Stone Tool Technology. Ethnoarchaeology 2020, 12, 118–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Hosfield, R. Lithic artifact assemblage transport and microwear modification in a fluvial setting: A radio frequency identification tag experiment. Geoarchaeology 2020, 35, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoville, B.J. Experimental lithic tool displacement due to long-term animal disturbance. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2019, 11, 5879–5891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelenfreund, A.; Pino, M.; Glascock, M.D.; Sinclaire, C.; Miranda, P.; Pasten, D.; Cancino, S.; Dinator, M.I.; Morales, J.R. Morphological and geochemical analysis of the Laguna Blanca/Zapaleri obsidian source in the Atacama Puna. Geoarchaeology 2010, 25, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, A.; Vázquez, M.; Avalos, J.; Angiorama, C. Prospecciones arqueológicas en la reserva “Eduardo Abaroa” (Sud Lípez, Depto. Potosí, Bolivia). Textos Antropológicos 2000, 11, 89–131. [Google Scholar]

- Shackley, S. Obsidian: Geology and Archaeology in the North American Southwest; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, M.C. Comparison Chart for Estimating Roundness and Sphericity: AGI; American Geological Institute: Alexandria, VA, USA, 1982; Data Sheet 18.1. [Google Scholar]

- Attal, M.; Lavé, J. Pebble abrasion during fluvial transport: Experimental results and implications for the evolution of the sediment load along rivers. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2009, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumbein, W.C. The effects of abrasion on the size, shape and roundness of rock fragments. J. Geol. 1941, 49, 482–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenen, P.H. Experimental erosion of pebbles: 2. Rolling by current. J. Geol. 1956, 64, 336–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, J.; Brewer, P.A. Laboratory simulation of clast abrasion. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2002, 27, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experiment Number | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Time (min) | 21 | 85 | 170 | 255 | 340 | 425 | 600 |

| Distance (km) | 0.7 | 3 | 5.5 | 8.5 | 11 | 14 | 20 |

| Initial Mass (g) | Final Mass (g) | Lost Mass (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural clasts | 1271 | 1209 | 5 |

| Broken clasts | 911 | 810 | 12 |

| Transport Distance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.7 | 3 | 5.5 | 8.5 | 11 | 14 | 20 | |

| Natural clasts | 0–1 | 0–9 | 3–18 | 6–25 | 12–36 | 15–47 | 20–70 |

| Broken clasts | 0–3 | 0–10 | 5–22 | 8–29 | 12–37 | 15–42 | 19–65 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Madrigal, C.; Lledó, H.; Fritte, D.; Pino, M. Experimental Development of Transport Percussion Marks on Obsidian Clasts, Pilauco Site, Chilean Northwestern Patagonia. Minerals 2022, 12, 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/min12030343

Madrigal C, Lledó H, Fritte D, Pino M. Experimental Development of Transport Percussion Marks on Obsidian Clasts, Pilauco Site, Chilean Northwestern Patagonia. Minerals. 2022; 12(3):343. https://doi.org/10.3390/min12030343

Chicago/Turabian StyleMadrigal, Catalina, Haroldo Lledó, Daniel Fritte, and Mario Pino. 2022. "Experimental Development of Transport Percussion Marks on Obsidian Clasts, Pilauco Site, Chilean Northwestern Patagonia" Minerals 12, no. 3: 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/min12030343

APA StyleMadrigal, C., Lledó, H., Fritte, D., & Pino, M. (2022). Experimental Development of Transport Percussion Marks on Obsidian Clasts, Pilauco Site, Chilean Northwestern Patagonia. Minerals, 12(3), 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/min12030343