Geometallurgical Characterization of the Arthur River Magnesite Deposit, Northwestern Tasmania for Pathways to Production

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Background

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Samples

3.2. Drill Core Logging Procedure

3.3. Hyperspectral Mineralogy

3.4. Optical Microscopy and Carbonate Staining

3.5. Mineralogical Studies

3.6. Geochemical Elemental (Major and Minor) Composition by pXRF and LA-ICPMS

4. Results

4.1. Ore Type Definition

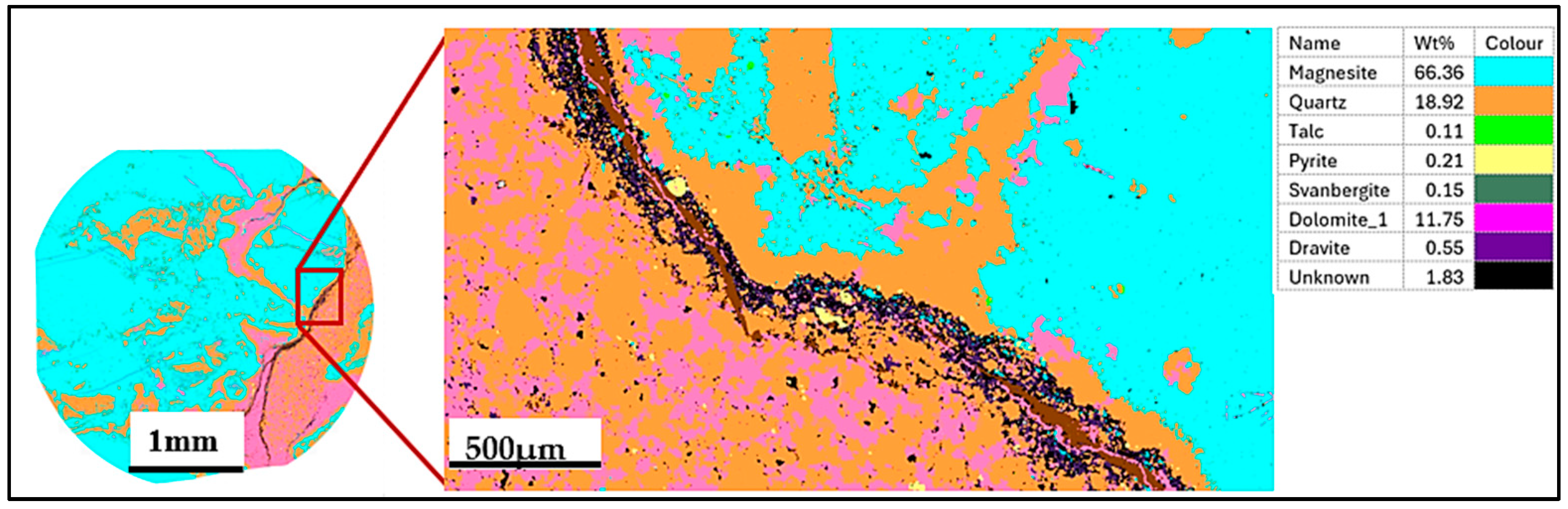

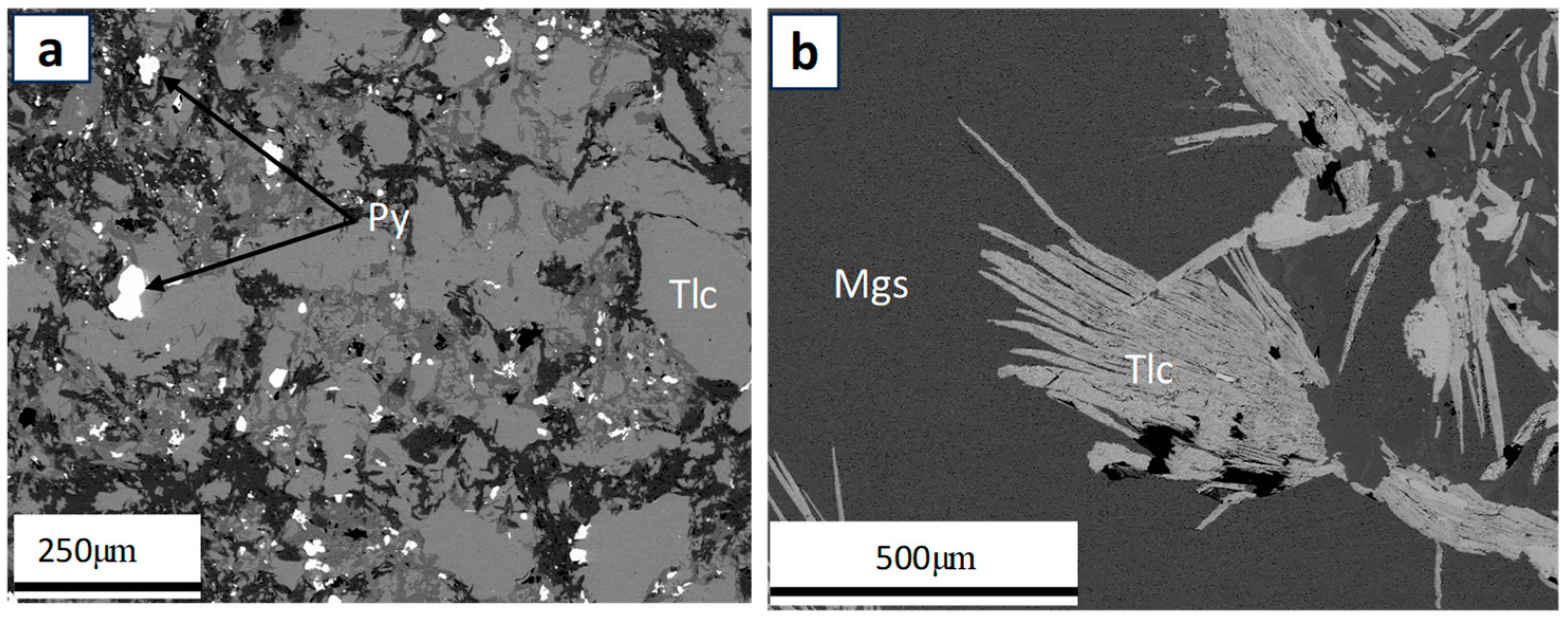

4.2. Ore–Gangue Mineral Composition and Structural–Textural Characteristics

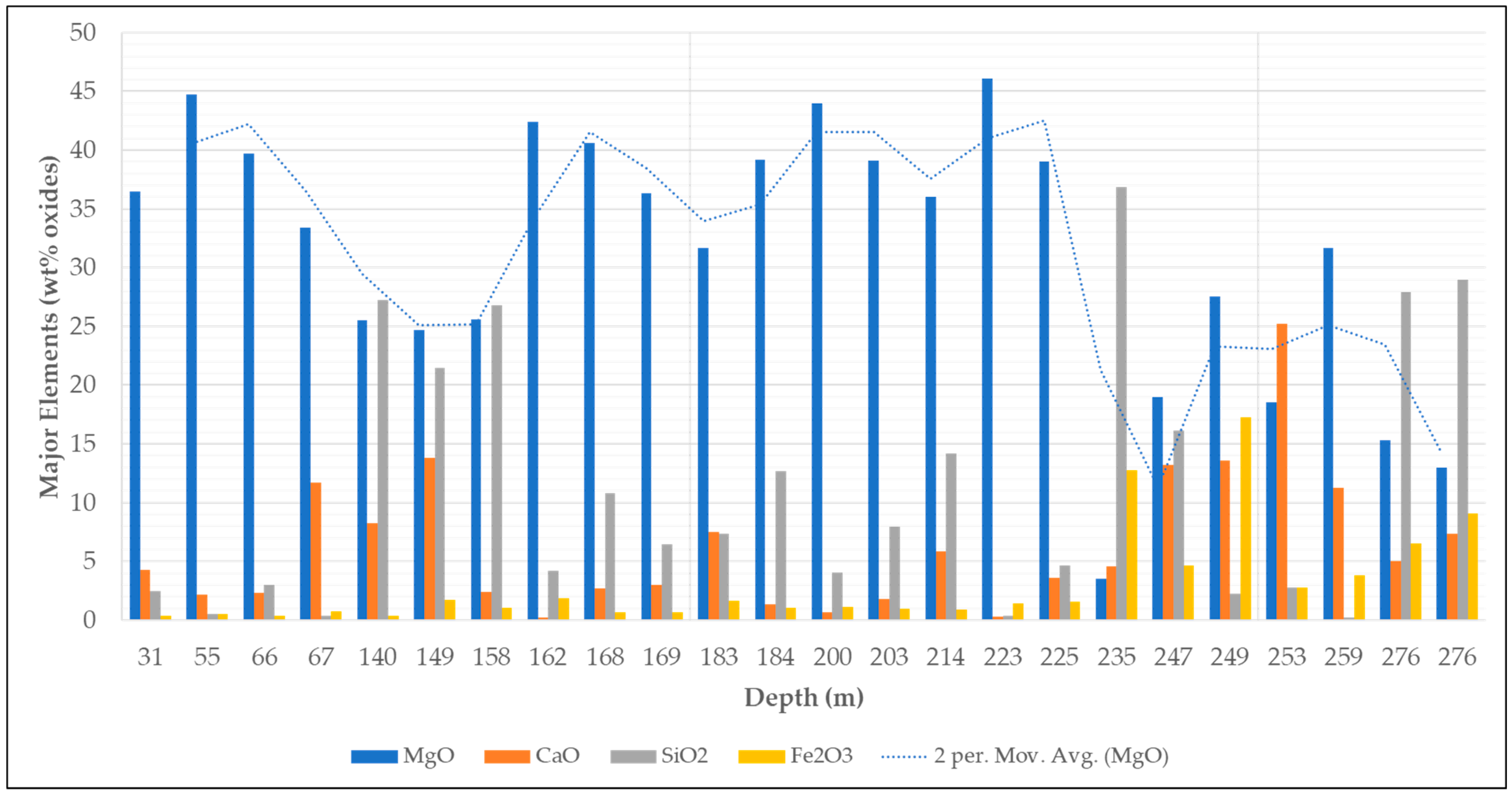

4.3. Chemical Composition of Magnesite Ore

5. Discussion

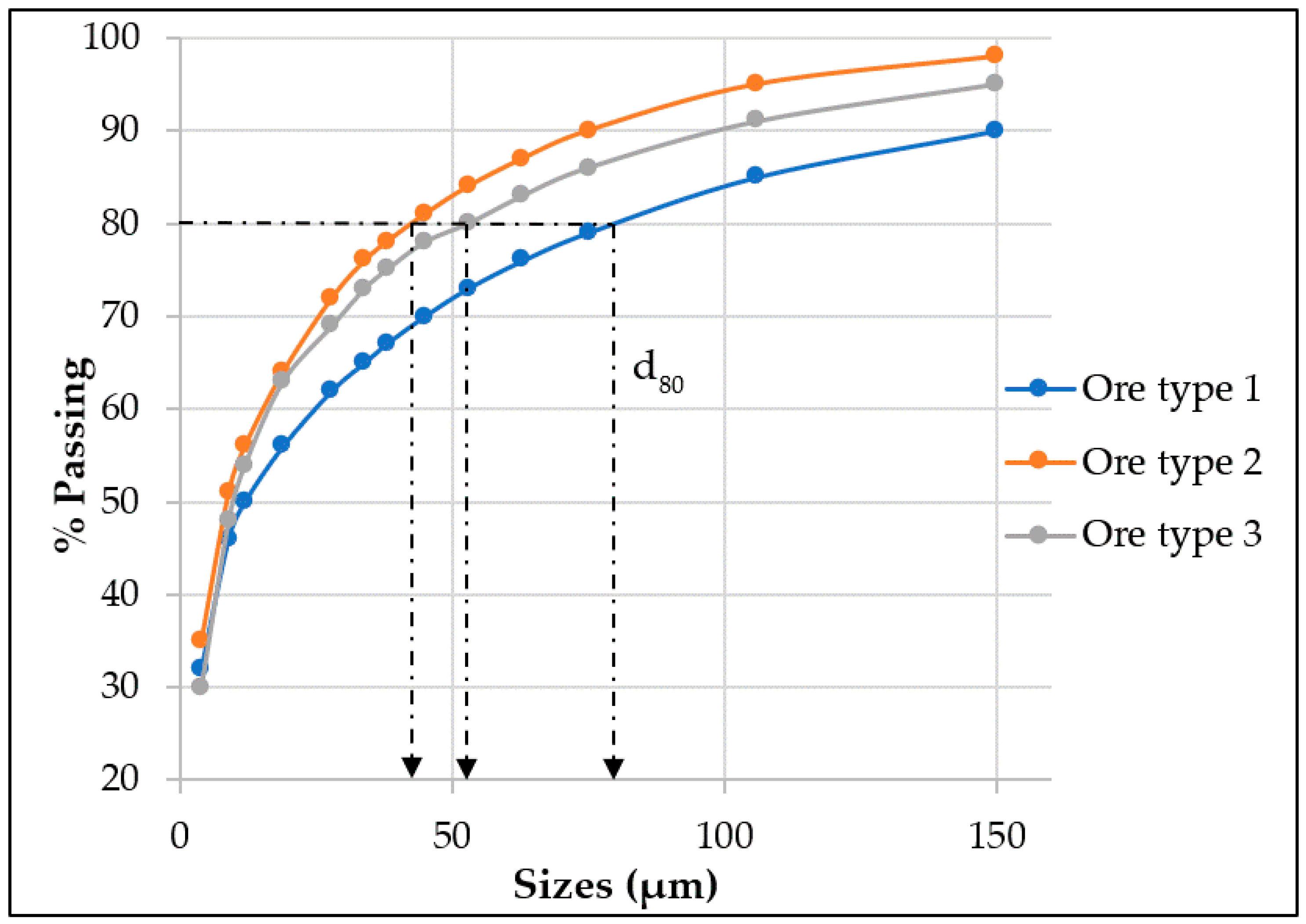

5.1. Particle Size Distribution (PSD)

5.2. Liberation

5.3. Beneficiation Routes

5.3.1. Type 1 and Type 2 Magnesite Ore

5.3.2. Type 3 Magnesite Ore

5.3.3. Flotation

6. Conclusions

- The preliminary characterization of the Arthur River magnesite deposit reveals that this deposit could be exploited for Mg critical metal production potential in Tasmania. However, the ore is closely associated with dolomite gangue. Consequently, the comprehensive study of potential ore processing routes is imperative to effectively separate magnesite from dolomite and enhance ore quality.

- Given the substantial ore body variations indicated by geochemical data, diverse ore types may necessitate distinct preconcentration beneficiation pathways. For example, the desirable standard for magnesite concentrate typically encompasses 40%–45% MgO, <5% SiO2, <2% CaO, 1%–2% Fe2O3, 0.05%–0.5% MnO, and 0.01%–0.1% TiO2. Ore type 1 might readily undergo flotation for the separation of calcium-bearing minerals (such as dolomite and calcite) from magnesite, meeting the specified standards without preconcentration methods like gravity or magnetic separation. However, ore types 2 and 3 may necessitate a clearly defined preconcentration step before flotation to achieve the desired outcomes.

- The petrographic studies with the optical microscope revealed that ore type 3 may be the challenging ore type for mineral processing, as a pre-flotation stage may be required to remove the pyrite before the commencement of the main flotation stream. Also, given that the mineralogy of ore type 1 and 2 are similar, the same processing route could be applied to both ore types to recover magnesite from dolomite, quartz, and talc.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tan, J.; Ramakrishna, S. Applications of magnesium and its alloys: A review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hycnar, E.; Sęk, M.; Ratajczak, T. Magnesite as a Sorbent in Fluid Combustion Conditions—Role of Magnesium in SO2 Sorption Process. Minerals 2023, 13, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drnek, T.L.; Moraes, M.N.; Neto, P.B. Overview of magnesite. J. Refract. Innov. RHIM Bull. 2018, 1, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne, J. Magnesium Market Highlights Continuing Fragility of Global Supply Chains; Australian Strategic Policy Institute: Barton, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Australia. Critical minerals at Geoscience Australia. Available online: https://www.ga.gov.au/scientific-topics/minerals/critical-minerals (accessed on 26 April 2023).

- Burton, J. U.S. Geological Survey Releases 2022 List of Critical Minerals. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/news/national-news-release/us-geological-survey-releases-2022-list-critical-minerals (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- European Commission. Critical Raw Materials. Available online: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/sectors/raw-materials/areas-specific-interest/critical-raw-materials_en (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Government of Australia. Australian Critical Minerals Prospectus. Available online: https://www.globalaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-01/ATIC_Australian_Critical_Minerals_Jan_2024.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Feng, G.; Nie, Z.-R.; Wang, Z.-H.; Gong, X.-Z.; Zuo, T.-Y. Assessing environmental impact of magnesium production using Pidgeon process in China. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2008, 18, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Han, W.; Peng, Y. Life cycle greenhouse gases, energy and cost assessment of automobiles using magnesium from Chinese Pidgeon process. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, S.; Koltun, P. A comparison of the greenhouse impacts of magnesium produced by electrolytic and Pidgeon processes. Essent. Read. Magnes. Technol. 2016, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Liu, W.; Liu, W.; Li, P.; Shen, Y.; Dai, S. Utilization of a novel bisphosphonic acid surfactant for reverse froth flotation of magnesite and dolomite. Miner. Eng. 2022, 185, 107668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, N.; Shi, J.; Yan, B.; Wang, X. Flotation Separation of Magnesite from Dolomite Using Sodium Silicate Modified with Zinc Sulfate as a Selective Depressant. Minerals 2024, 14, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Yin, W.; Yao, J.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, H.; Chen, K.; Cao, S. Selective collection and differential adsorption of pentaethoxylated laurylamine for the flotation recovery of magnesite from quartz. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 625, 126991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Dai, S.; Liu, W.; Li, P.; Duan, H.; Yu, X. Effect of Ca (II) on anionic/cationic flotation of magnesite ore. Miner. Eng. 2021, 163, 106778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, W.; Dai, S.; Yang, T.; Li, Z.; Fang, P. Enhancing the purity of magnesite ore powder using an ethanolamine-based collector: Insights from experiment and theory. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 268, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASX Announcements. GWR Completes Acquisition of Advanced Magnesium Project. Available online: https://wcsecure.weblink.com.au/pdf/GWR/02495658.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Rawlinson, N.; Tkalčić, H.; Reading, A.M. Structure of the Tasmanian lithosphere from 3D seismic tomography. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 2010, 57, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, G.R. Ore deposits and metallogenesis of Tasmania. Epis. J. Int. Geosci. 2012, 35, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.; Bottrill, R. Blue amphibole, Arthur Metamorphic Complex, Tasmania: Composition and regional tectonic setting. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 2001, 48, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, O.C. A Geophysical and Geological Study of the Arthur River Magnesite Deposit, Northwest Tasmania; University of Tasmania: Hobart, Australia, 2011; unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, M. The magnesite deposit at Main Creek, Savage River, Tasmania. Econ. Geol. 1982, 77, 1901–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broker, A. Red Rock Resources plc. Red. 2005. Available online: https://www.rrrplc.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Admission-Prospectus_290705_RRR.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Holm, O.; Berry, R. Structural history of the Arthur Lineament, northwest Tasmania: An analysis of critical outcrops. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 2002, 49, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, M.I. The Geological History of Tasmania with Special Reference to Events During the Palaeozoic Era. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, J. The Geology of the West Coast Range of Tasmania. In Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania; Palala Press: London, UK, 1954; Volume 88, pp. 193–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquhart, G. Magnetite Deposits of the Savage River-Rocky River Region; Tasmania Department of Mines: Burnie, Tasmania, 1966.

- Dickson, T.W. Arthur river and lyons river magnesite deposits. In Geology of Australian and Papua New Guinean Mineral Deposits; Berkman, D.A., MacKenzie, D.H., Eds.; Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Melbourne, Australia, 1990; pp. 1181–1183. [Google Scholar]

- Spate, A. Magnesite karst in Tasmania. Available online: https://ackma.org (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Mikkelsen, L.; Moesgaard, K.; Hegnauer, M.; Lopez, A.D. ANACONDA: A new tool to improve mortality and cause of death data. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwynn, X.; Brown, M.; Mohr, P. Combined use of traditional core logging and televiewer imaging for practical geotechnical data collection. In Proceedings of the Slope Stability 2013: Proceedings of the 2013 International Symposium on Slope Stability in Open Pit Mining and Civil Engineering, Brisbane, Australia, 25–27 September 2013; Australian Centre for Geomechanics: Crawley, Australia, 2013; pp. 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresia, B.; Ross, P.-S.; Gloaguen, E.; Bourke, A. Lithological discrimination based on statistical analysis of multi-sensor drill core logging data in the Matagami VMS district, Quebec, Canada. Ore Geol. Rev. 2017, 80, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schodlok, M.; Whitbourn, L.; Huntington, J.; Mason, P.; Green, A.; Berman, M.; Coward, D.; Connor, P.; Wright, W.; Jolivet, M. HyLogger-3, a visible to shortwave and thermal infrared reflectance spectrometer system for drill core logging: Functional description. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 2016, 63, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geologist, T.S. Unlocking the Secrets of The Spectral Geologist (TSG). Available online: https://spectralgeo.com.au/the-spectral-geologist-tsg-software (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Barber, D.; Wenk, H.-R. Deformation twinning in calcite, dolomite, and other rhombohedral carbonates. Phys. Chem. Miner. 1979, 5, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, O.; Parlangeau, C.; Beaudoin, N.E.; Amrouch, K. Calcite twin formation, measurement and use as stress–strain indicators: A review of progress over the last decade. Geosciences 2021, 11, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, G.M. Identification of carbonate minerals by staining methods. J. Sediment. Res. 1959, 29, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, J. A modified staining technique for carbonates in thin section. Nature 1965, 205, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, J. Carbonate identification and genesis as revealed by staining. J. Sediment. Res. 1966, 36, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruker AMICS Automated Mineralogy System for SEM. Available online: https://www.bruker.com/en/products-and-solutions/elemental-analyzers/eds-wds-ebsd-SEM-Micro-XRF/software-amics-automated-mineralogy-system.html (accessed on 11 March 2024).

- Jochum, K.P.; Weis, U.; Stoll, B.; Kuzmin, D.; Yang, Q.; Raczek, I.; Jacob, D.E.; Stracke, A.; Birbaum, K.; Frick, D.A. Determination of reference values for NIST SRM 610–617 glasses following ISO guidelines. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 2011, 35, 397–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GeoRem. GeoReM Preferred Values. Available online: http://georem.mpch-mainz.gwdg.de/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Longerich, H.P.; Jackson, S.E.; Günther, D. Inter-laboratory note. Laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometric transient signal data acquisition and analyte concentration calculation. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 1996, 11, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, A.; Danyushevsky, L. Towards Estimating the Complete Uncertainty Budget of Quantified Results Measured by LA-ICP-MS; Goldschmidt: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Green, D.; Schodlok, M. Characterisation of carbonate minerals from hyperspectral TIR scanning using features at 14,000 and 11,300 nm. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 2016, 63, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Peng, Y.; Runge, K.; Bradshaw, D. A review of entrainment: Mechanisms, contributing factors and modelling in flotation. Miner. Eng. 2015, 70, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eswaraiah, C.; Gupta, A.; Nagarajan, R.; Rajavel, M.; Nandakumar, K. Minimization of fines generation in size reduction of coals by impact crusher. Fuel Process. Technol. 2008, 89, 704–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariano, R.; Evans, C.; Manlapig, E. Definition of random and non-random breakage in mineral liberation—A review. Miner. Eng. 2016, 94, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromans, D. Mineral comminution: Energy efficiency considerations. Miner. Eng. 2008, 21, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, N. The Best Suitable Beneficiation Method for Magnesite Ore. Organ. Comm. Honor. Chair 2017, 265. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/380637989_The_best_suitable_beneficiation_method_for_magnesite_ore (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Burt, R. Gravity concentration methods. In Mineral Processing Design; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1987; pp. 106–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S. Recovery improvement of fine iron ore particles by multi gravity separation. Open Miner. Process. J. 2009, 2, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbayoglu, G.; Atalay, M.Ü. Beneficiation of bastnaesite by a multi-gravity separator. J. Alloys Compd. 2000, 303, 520–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, A. Gravity separation: Old technique/new methods. Phys. Sep. Sci. Eng. 2003, 12, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojamberdiev, M.; Arifov, P.; Tadjiev, K.; Yunhua, X. Characterization and processing of talc-magnesite from the Zinelbulak deposit. Min. Sci. Technol. 2010, 20, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudin, A.; Spedden, H. Magnetic separation of sulphide minerals. AIME Trans. 1943, 153, 563–575. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, Y.; Peng, Y.; Lauten, R.A. The depression of pyrite in selective flotation by different reagent systems—A Literature review. Miner. Eng. 2016, 96, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozun, S.; Hassas, B.V.; Miller, J.D. Collectorless flotation of oxidized pyrite. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 561, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicyilmaz, C.; Altun, N.E.; Ekmekci, Z.; Gokagac, G. Pyrite–DTPI interaction as a function of pulp potential and pH. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2004, 233, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Peng, Y.; Parker, G. Electrochemical and spectroscopic studies of pyrite–cyanide interactions in relation to the depression of pyrite flotation. Miner. Eng. 2016, 92, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, E.; Sherman, D.; Purton, J. Surface oxidation of pyrite under ambient atmospheric and aqueous (pH = 2 to 10) conditions: Electronic structure and mineralogy from X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2003, 67, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Gharabaghi, M.; Abdollahi, H. Effects of type and dosages of organic depressants on pyrite floatability in microflotation system. Adv. Powder Technol. 2018, 29, 3155–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Han, Y.; Gu, X.; Wang, S. Adsorption mechanism of a new depressant on pyrite surfaces and its application to the selective separation of chalcopyrite from pyrite. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 625, 126892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yang, H.-Y.; Tong, L.-L.; Niu, H.-Q.; Zhang, F.-S.; Chen, G.-M. Research and application of a Knelson concentrator: A review. Miner. Eng. 2020, 152, 106339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeavy, M.J. Continuous Centrifugal Concentrator Operation and Control. Ph.D. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, D.; Yang, B.; Yin, W.; Ardakani, M.S.; Yao, J.; Drelich, J.W. Effect of nano-sized roughness on the flotation of magnesite particles and particle-bubble interactions. Miner. Eng. 2020, 151, 106340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Huang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Li, F. Flotation separation of magnesite from dolomite with gellan gum as depressant and its depression mechanism. Miner. Eng. 2024, 212, 108718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yin, W.; Yang, B.; Han, F. Simultaneous separation of quartz and dolomite from magnesite using monosodium phosphate as a regulator via reverse flotation. Miner. Eng. 2021, 172, 107185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leterme, P.; Gayot, A.; Finet, G.; Bizi, M.; Flament, M. Influence of the morphogranulometry and hydrophobicity of talc on its antisticking power in the production of tablets. Int. J. Pharm. 2005, 289, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ann Bazar, J.; Rahimi, M.; Fathinia, S.; Jafari, M.; Chipakwe, V.; Chehreh Chelgani, S. Talc flotation—An overview. Minerals 2021, 11, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezáni, I.; Zeleňák, F.; Zeleňák, M. Collectorless flotation of talc-magnesite ore with respect to particle size. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2013, 18, 198. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Chen, T.; Shao, Y.; Ye, G.; Tong, X. The flotation separation of molybdenite from talc using zinc sulfate in sodium silicate system and related mechanism. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 641, 128451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melo, C.; de Araujo, A.C.; Filippov, L. Reverse cationic flotation of iron ores with complex silicate gangue minerals. In Proceedings of the Iron Ore 2017, Perth, Australia, 24–26 July 2017; pp. 241–244. [Google Scholar]

| Drill Hole ID | Procedure | Sample Type | No. of Samples | Length of Drill Hole (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DD83AR002 | Drill core logging using the anaconda method/optical mineralogy/staining for carbonates | Diamond drill core/polished thin sections | 52 | 244.5 |

| DD83AR0016 | Hyperspectral (SWIR and TIR) analysis: logging with/HyLogger-3/LA-ICPMS/pXRF | Diamond drill core | 26 | 239 |

| DD83AR007 | pXRF | Diamond drill core | 21 | 282.5 |

| AR035/AR036/AR037/AR038 | SEM | SEM tiles | 39 | 145.7/99.8/123.5/115.4 |

| Type 1 (T1) | Type 2 (T2) | Type 3 (T3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MgO | ≥40% | ≥30% | ≥20% |

| SiO2 | ≤10% | ≤25% | ≤50% |

| CaO | ≤2.5% | ≤7.5% | ≤25% |

| Fe2O3 | ≤1% | ≤5% | ≤30% |

| Al2O3 | ≤0.05% | ≤2.5% | ≤10% |

| wt% | PPM | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types | Item | Mg | Ca | Si | Fe | Mn | Na | Sr | P | Zn | K | Cu | Al | Ni | Co | Li |

| Type 1 (n = 18) | Minimum | 26.16 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 3.61 | 9.92 | 4.85 | 3.44 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.63 |

| Maximum | 28.68 | 2.80 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 22.7 | 28.52 | 18.64 | 21.8 | 0.56 | 0.66 | 2.08 | 0.43 | 1.73 | |

| Mean | 27.98 | 0.79 | 0.29 | 0.40 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 9.25 | 18.76 | 10.00 | 7.19 | 0.22 | 0.42 | 0.83 | 0.19 | 1.00 | |

| Median | 28.33 | 0.27 | 0.03 | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 7.11 | 19.14 | 9.09 | 4.46 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.66 | 0.22 | 0.86 | |

| Std Dev | 0.94 | 1.05 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 7.02 | 6.04 | 4.66 | 7.24 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.79 | 0.16 | 0.42 | |

| Type 2 (n = 13) | Minimum | 27.00 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 2.55 | 0.09 | 7.80 | 5.86 | 1.24 | 0.08 | 1.76 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Maximum | 28.71 | 0.69 | 0.52 | 2.29 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 16.2 | 27.37 | 30.77 | 52.7 | 0.42 | 8.73 | 7.94 | 2.24 | 0.66 | |

| Mean | 28.00 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 1.09 | 0.12 | 0.011 | 2.43 | 14.87 | 17.14 | 15.0 | 0.18 | 4.79 | 2.08 | 0.76 | 0.20 | |

| Median | 28.22 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.77 | 0.10 | 0.013 | 1.56 | 13.16 | 11.09 | 11.7 | 0.12 | 3.31 | 2.29 | 0.23 | 0.16 | |

| Std Dev | 0.52 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.73 | 0.05 | 0.012 | 4.25 | 6.66 | 19.90 | 14.8 | 0.13 | 2.53 | 3.19 | 0.87 | 0.18 | |

| Type 3 (n = 17) | Minimum | 26.15 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 1.39 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 14.58 | 2.92 | 2.62 | 0.11 | 5.62 | 9.82 | 0.58 | 0.12 |

| Maximum | 27.58 | 0.09 | 2.80 | 2.55 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 8.96 | 20.21 | 17.03 | 24.37 | 2.39 | 30.11 | 16.82 | 0.86 | 1.25 | |

| Mean | 27.09 | 0.08 | 0.59 | 2.06 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 4.43 | 13.79 | 9.78 | 13.79 | 0.92 | 13.88 | 12.34 | 0.43 | 0.57 | |

| Median | 27.19 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 2.03 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 4.28 | 17.33 | 8.10 | 17.21 | 0.19 | 7.43 | 11.84 | 0.49 | 0.50 | |

| Std Dev | 0.58 | 0.01 | 1.23 | 0.49 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 3.36 | 2.39 | 6.29 | 9.92 | 1.08 | 10.64 | 2.79 | 0.33 | 0.42 | |

| Minerals of Interest | Mainly Liberated (75% < x ≤ 100%) | Moderately Liberated (50% < x ≤ 75%) | Poorly Liberated (0% < x ≤ 50%) | d80 | d50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnesite | 93.43 | 3.99 | 2.58 | 64 | 28 |

| Dolomite | 86.08 | 7.21 | 3.07 | 72 | 27 |

| Quartz | 85.7 | 6.05 | 4.41 | 72 | 36 |

| Talc | 29.3 | 28.16 | 28.51 | 19 | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Appiah, A.A.A.; Hunt, J.; Fathi, M.; Missen, O.P.; Hong, W.; Belousov, I.; Kameniar-Sandery, V.; Wilson, M. Geometallurgical Characterization of the Arthur River Magnesite Deposit, Northwestern Tasmania for Pathways to Production. Minerals 2025, 15, 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030247

Appiah AAA, Hunt J, Fathi M, Missen OP, Hong W, Belousov I, Kameniar-Sandery V, Wilson M. Geometallurgical Characterization of the Arthur River Magnesite Deposit, Northwestern Tasmania for Pathways to Production. Minerals. 2025; 15(3):247. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030247

Chicago/Turabian StyleAppiah, Alfredtina Akua Abrafi, Julie Hunt, Mohammadbagher Fathi, Owen P. Missen, Wei Hong, Ivan Belousov, Verity Kameniar-Sandery, and Mick Wilson. 2025. "Geometallurgical Characterization of the Arthur River Magnesite Deposit, Northwestern Tasmania for Pathways to Production" Minerals 15, no. 3: 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030247

APA StyleAppiah, A. A. A., Hunt, J., Fathi, M., Missen, O. P., Hong, W., Belousov, I., Kameniar-Sandery, V., & Wilson, M. (2025). Geometallurgical Characterization of the Arthur River Magnesite Deposit, Northwestern Tasmania for Pathways to Production. Minerals, 15(3), 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030247