Economic Valuation of Metal Recovery from Mobile Phones in India

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. E-Waste Generation

1.2. Mobile Phone E-Waste

1.3. The Indian Scenario

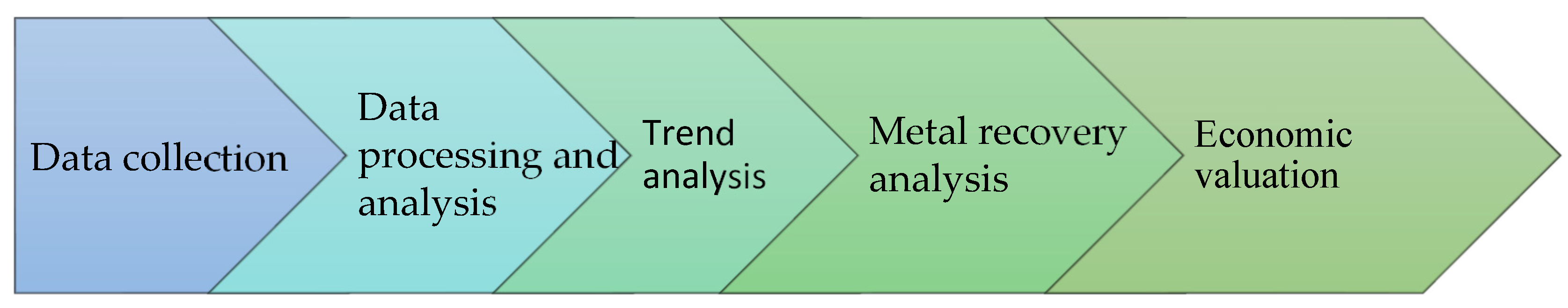

2. Methodology

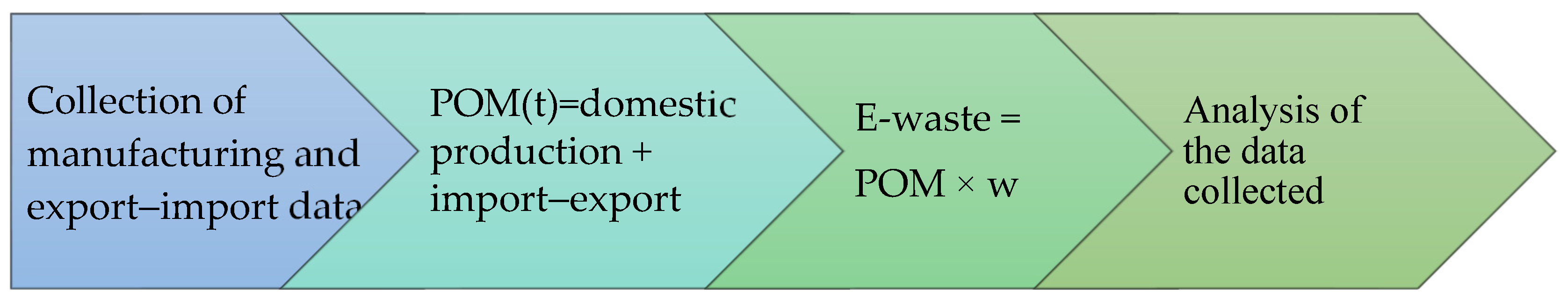

2.1. Estimation of Put on Market (POM) of Mobile Phones

2.2. Weibull Probability Distribution Function

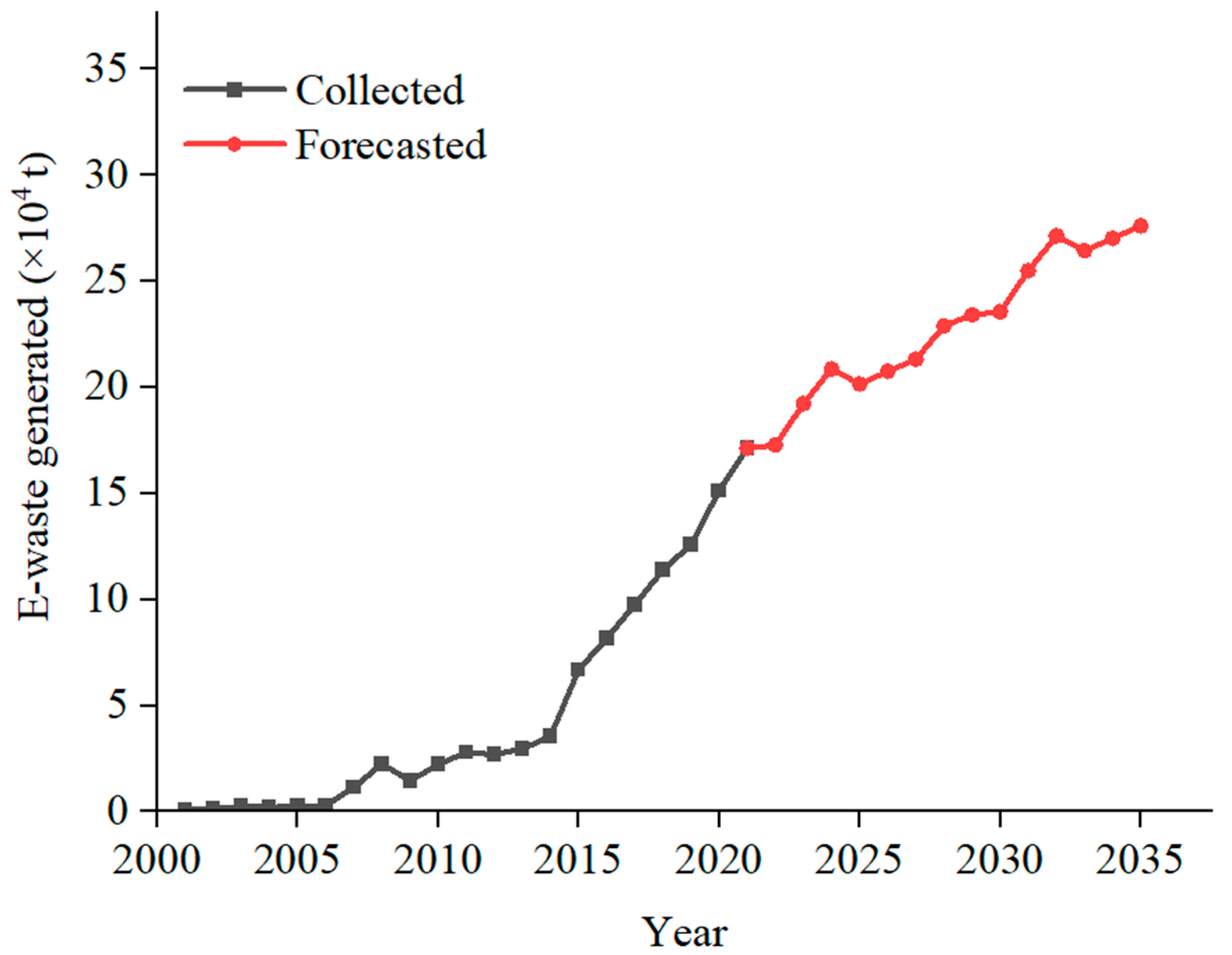

2.3. Estimation of E-Waste Generation from Rejected Mobile Phones

2.4. Metal Recovery from PCB and Display of Mobile Phones

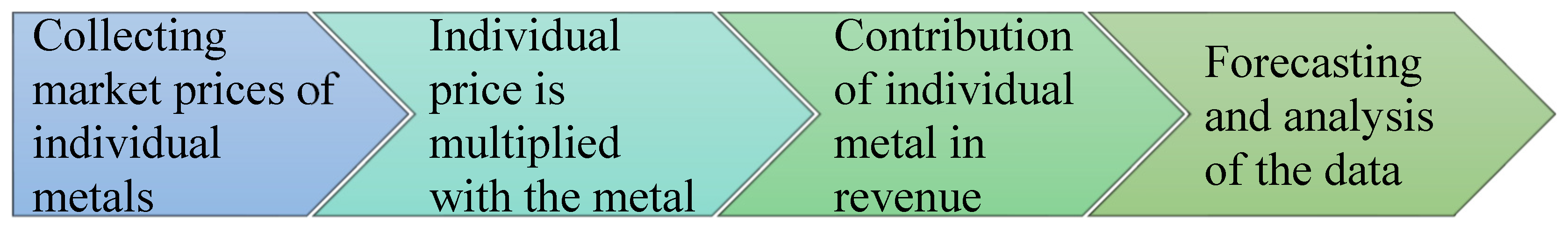

2.5. Estimation and Forecasting of Economic Valuation in Revenue

3. Results and Discussion

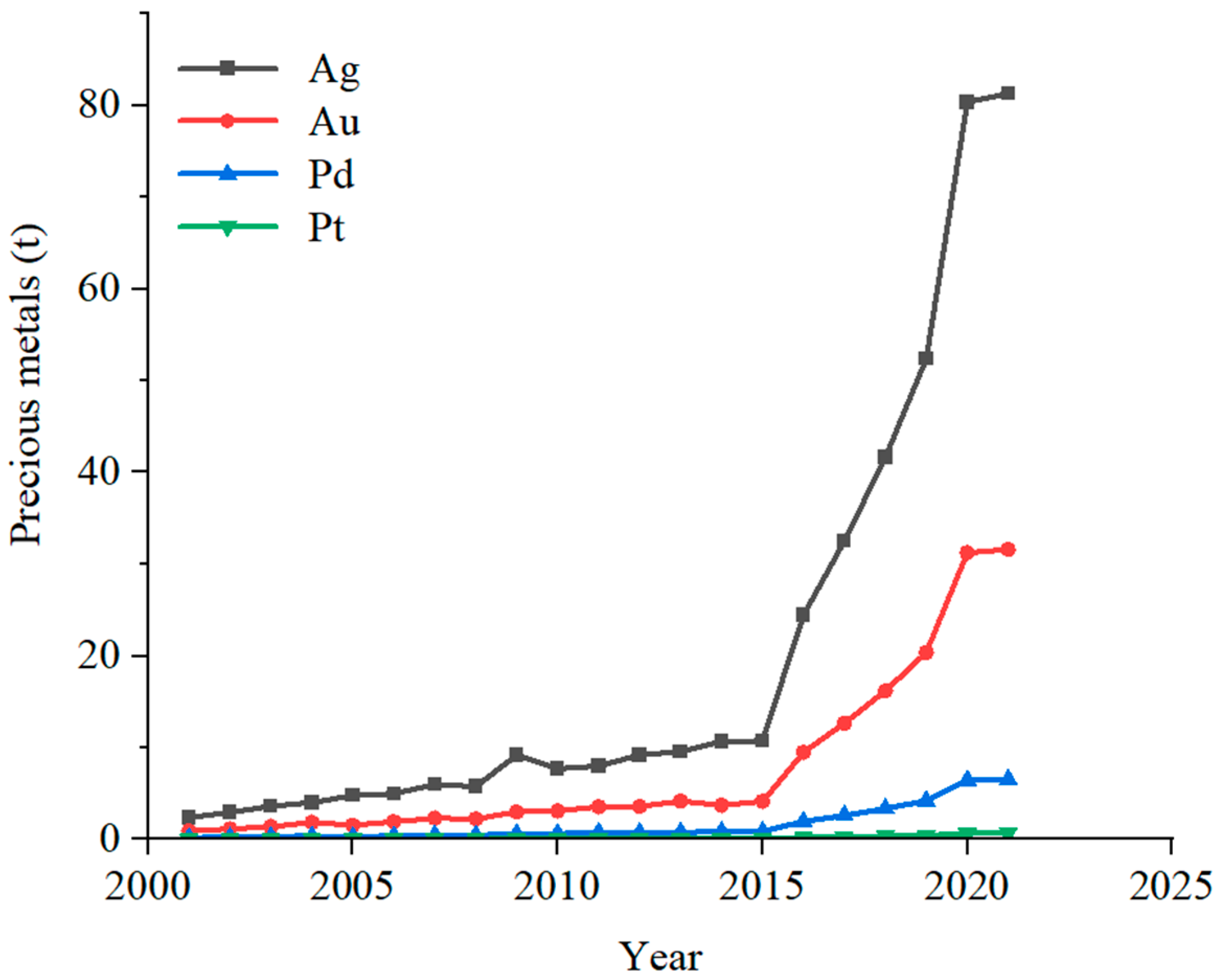

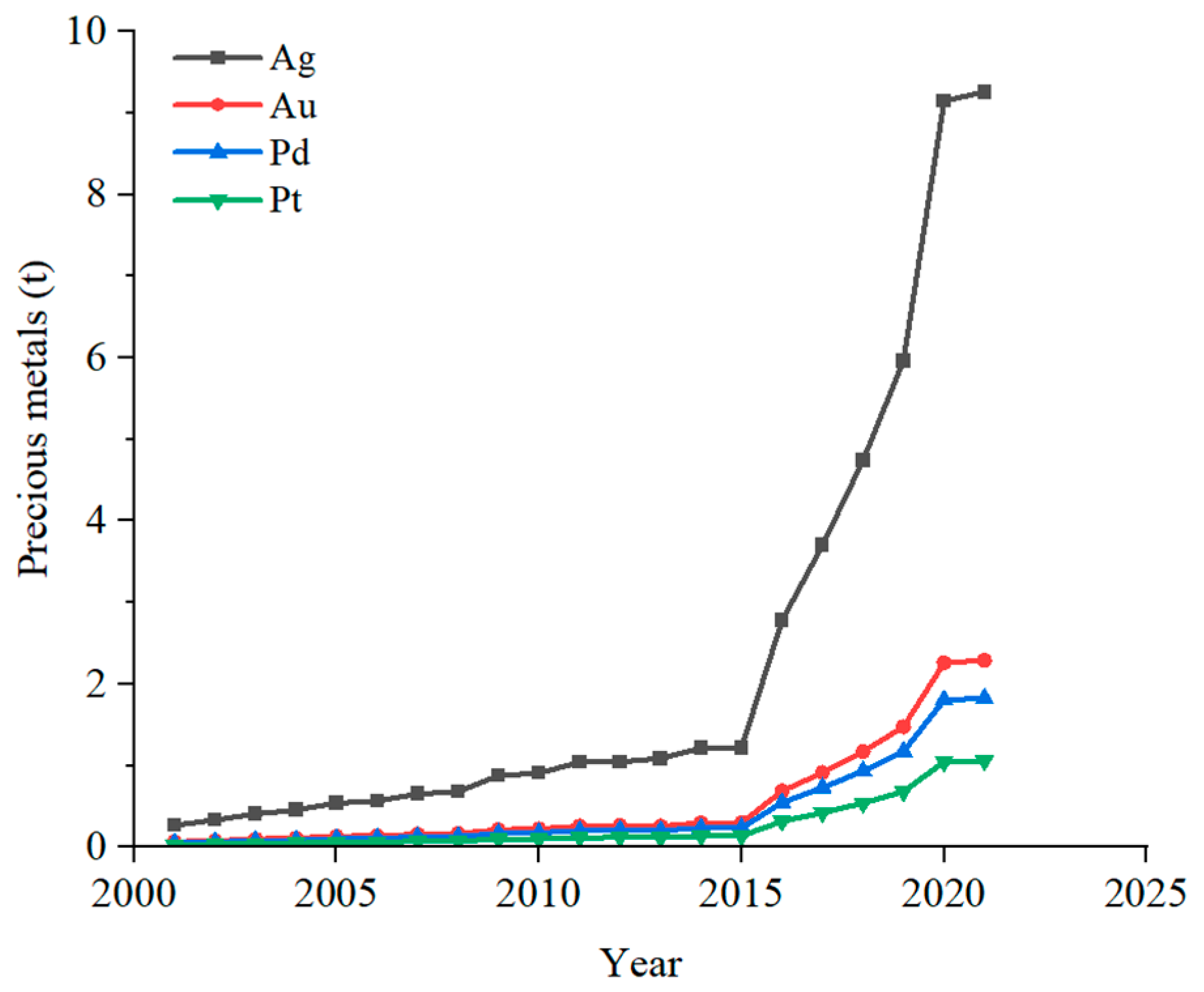

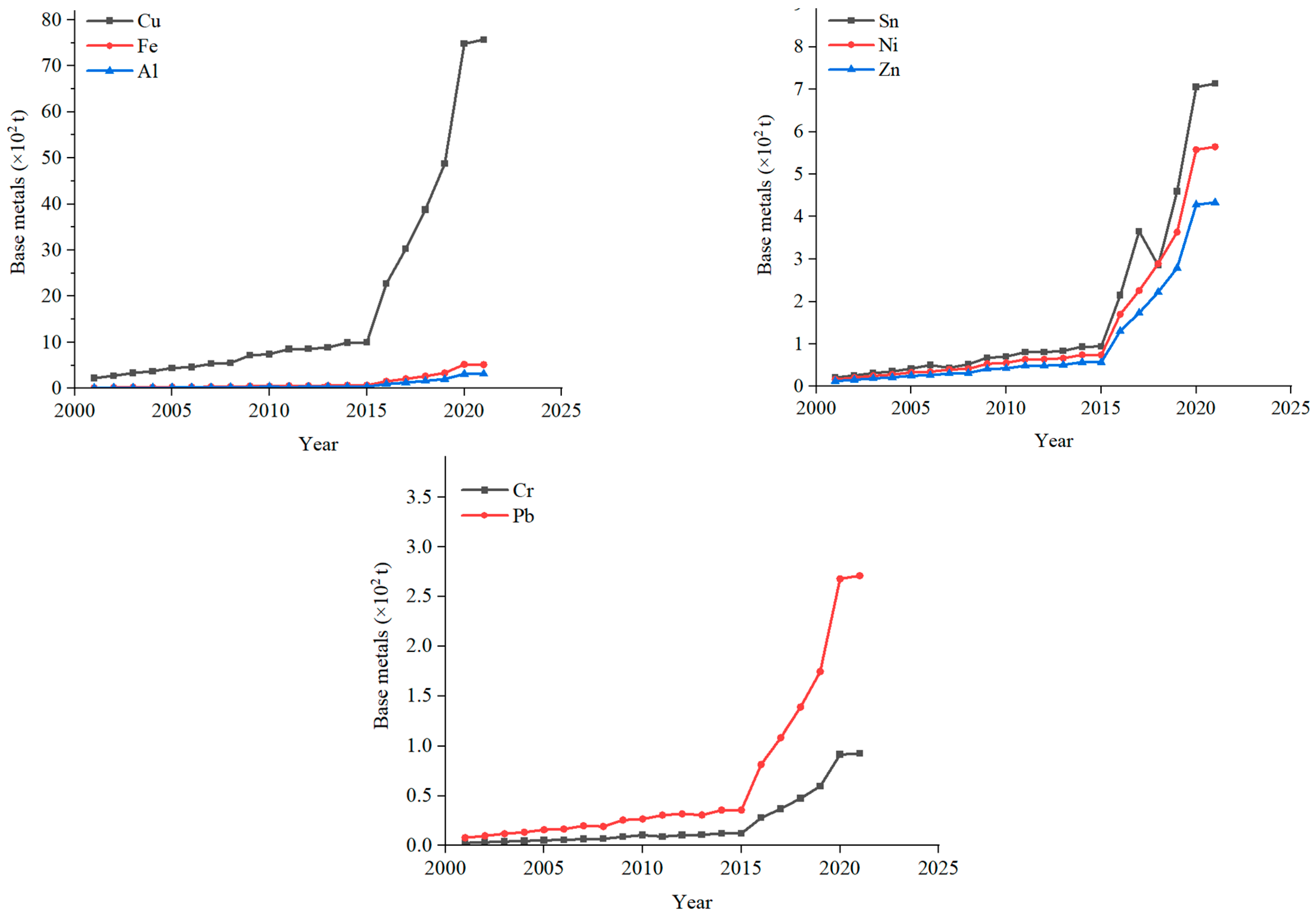

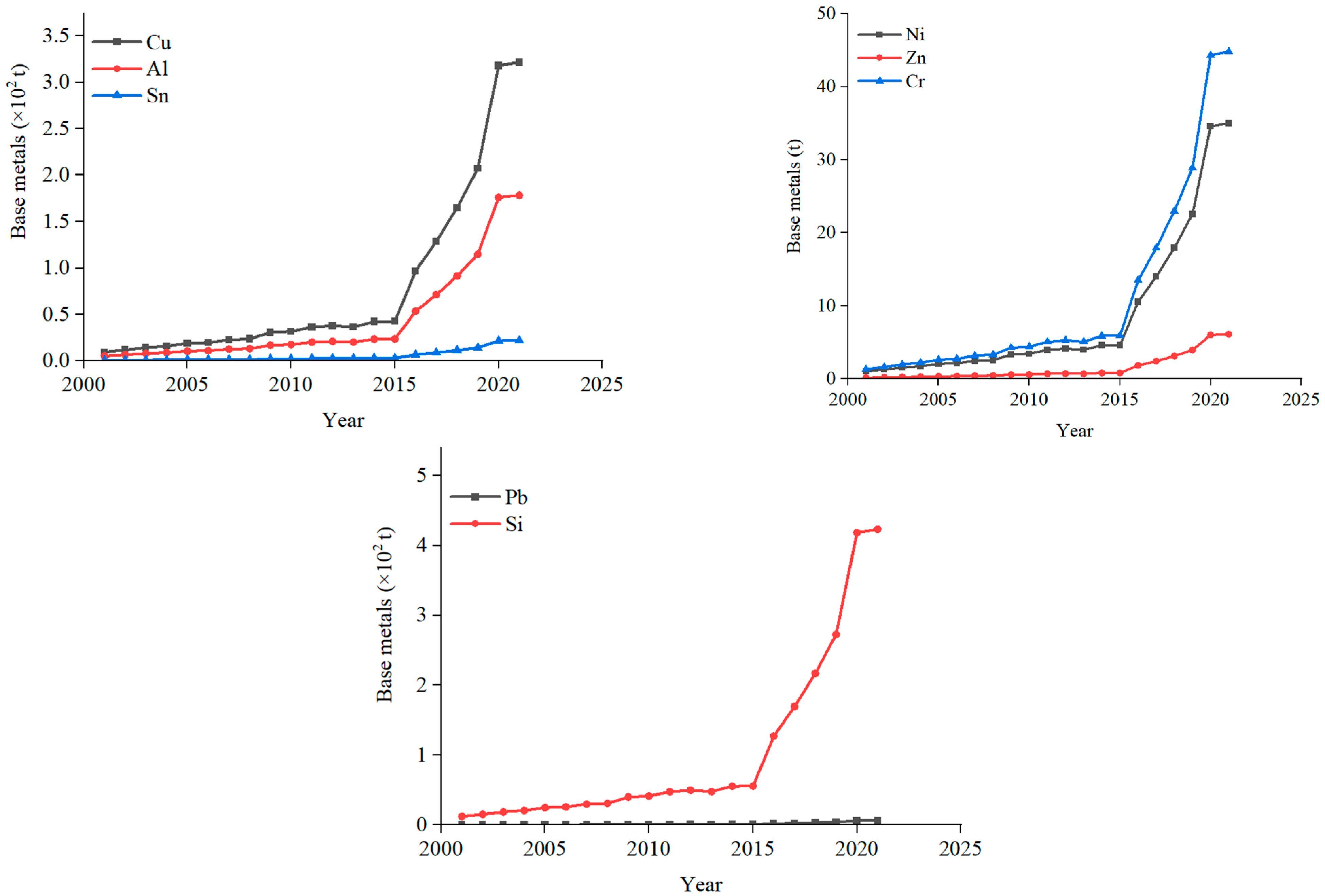

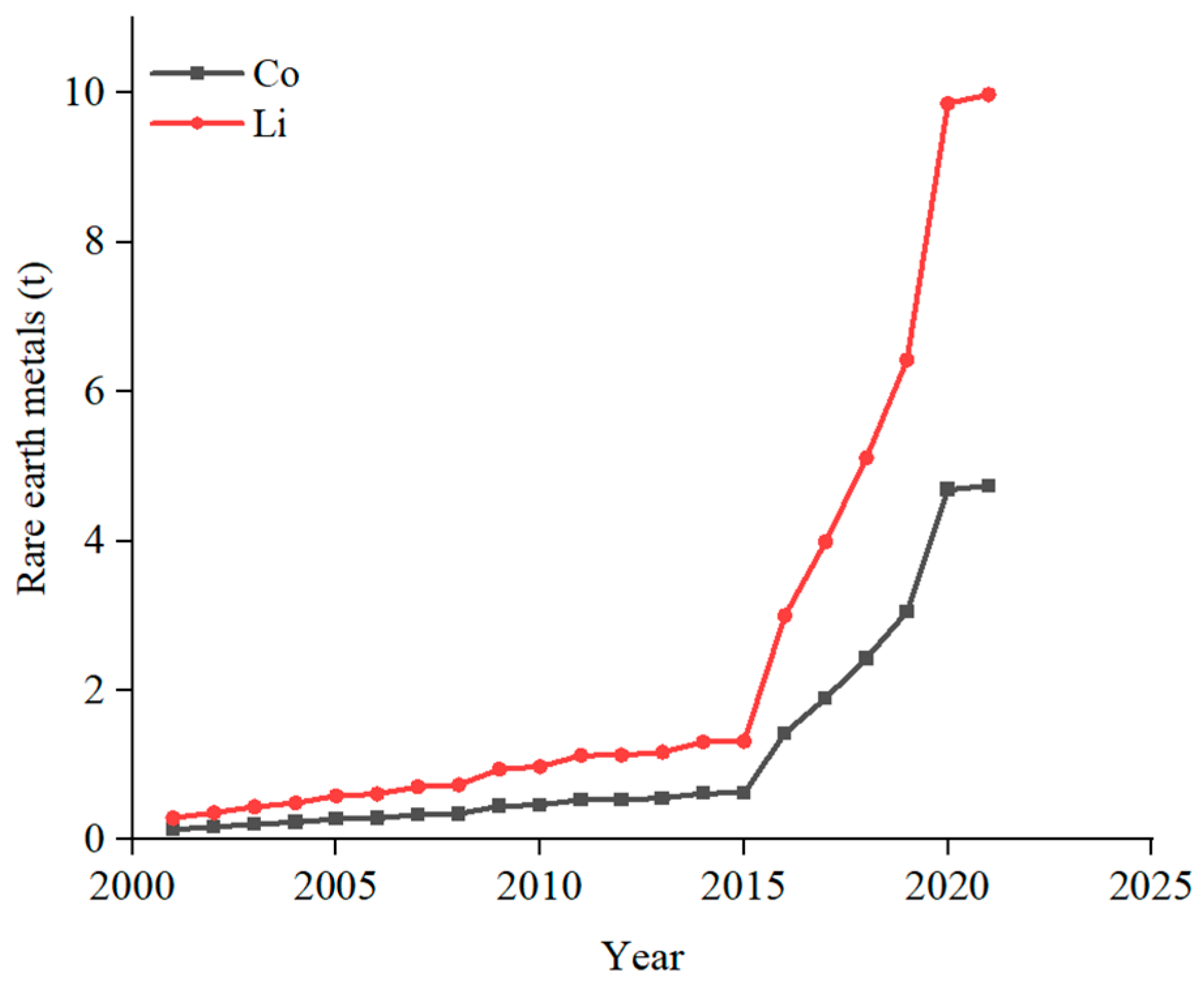

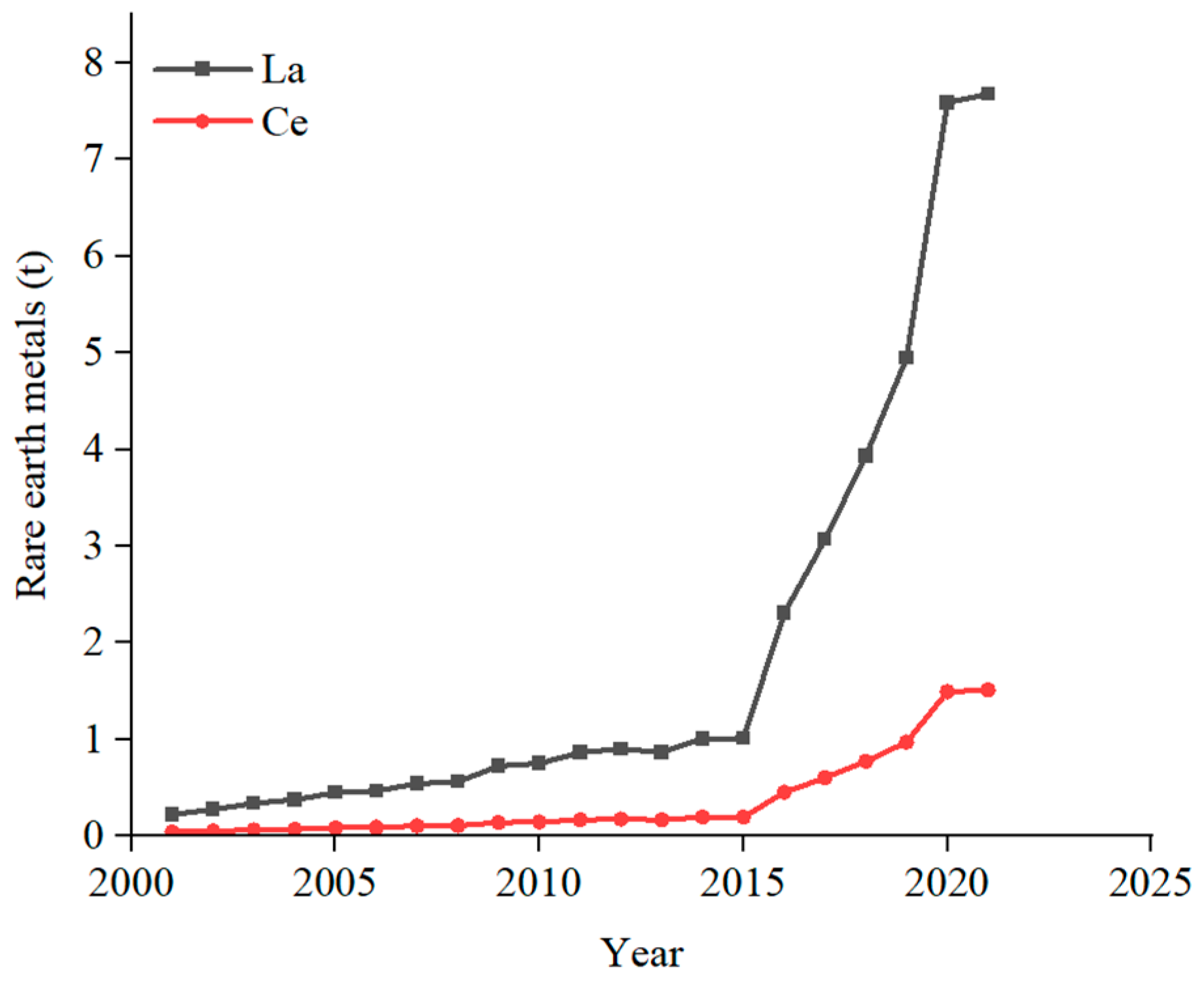

3.1. Metal Recovery

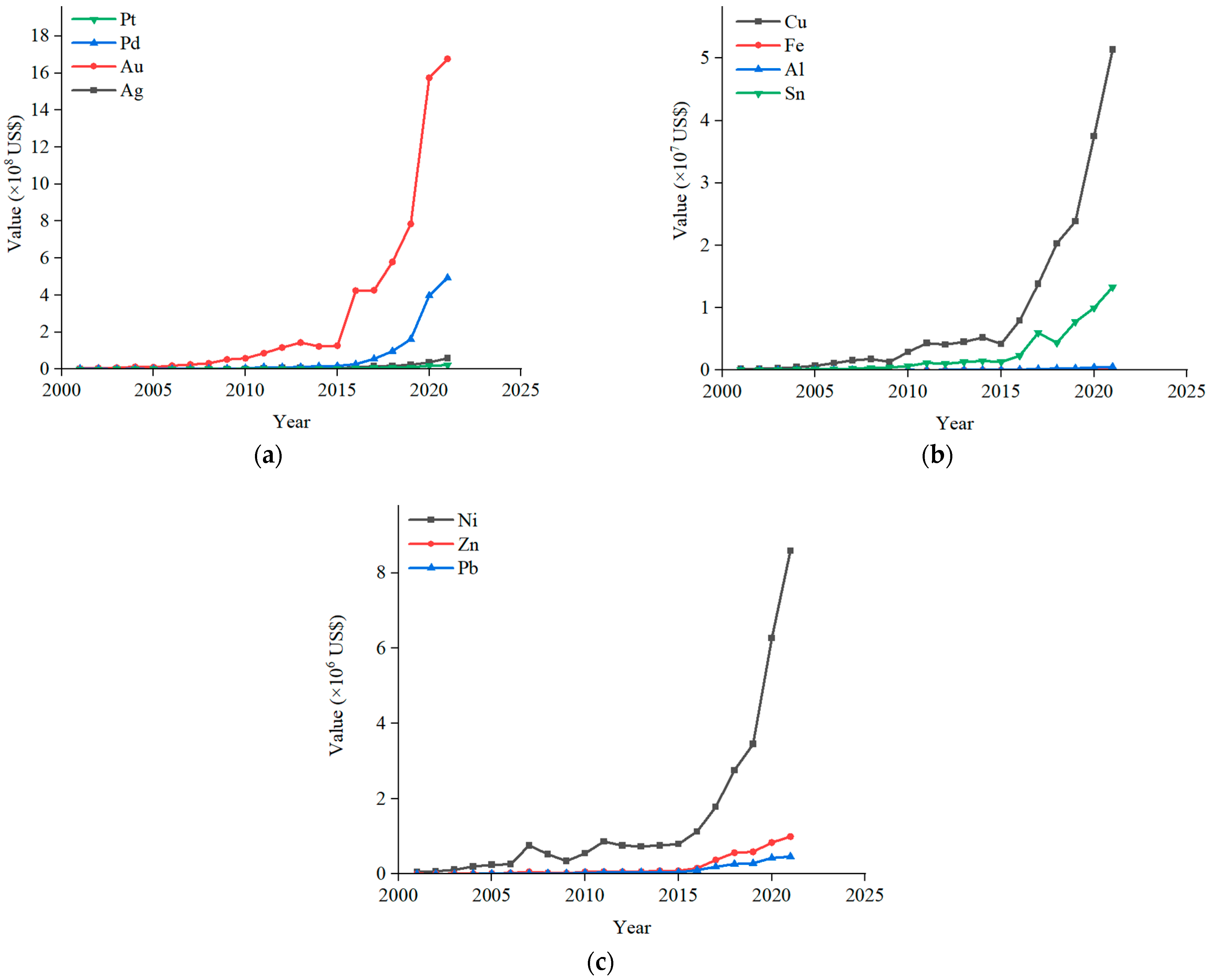

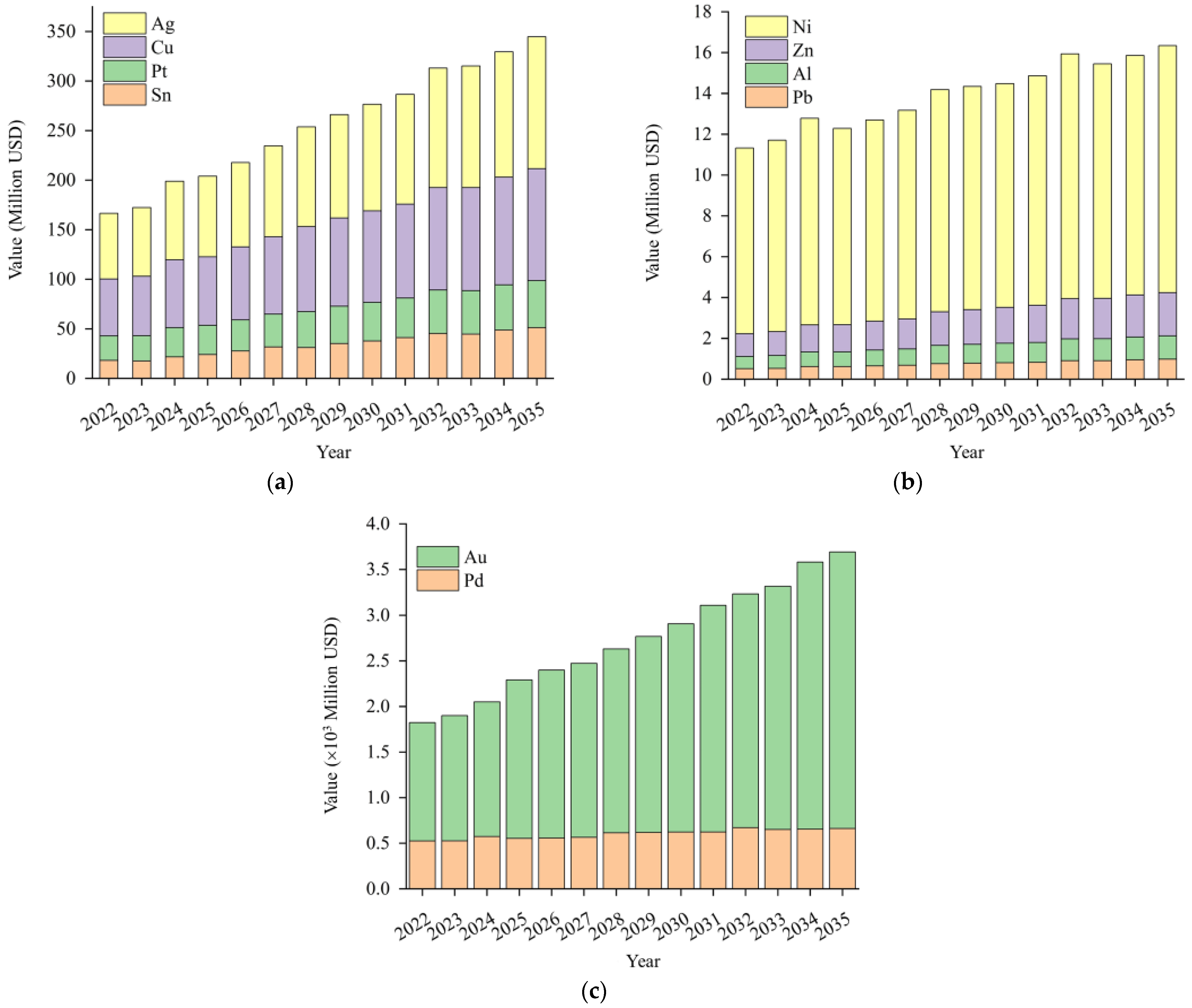

3.2. Economic Valuation from Forecasting for Valuation

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Quintero-Almanza, D.; Gamiño-Arroyo, Z.; Sánchez-Cadena, L.E.; Gómez-Castro, F.I.; Uribe-Ramírez, A.R.; Aguilera-Alvarado, A.F.; Ocampo Carmona, L.M. Recovery of cobalt from spent lithium-ion mobile phone batteries using liquid–liquid extraction. Batteries 2019, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vats, M.C.; Singh, S.K. Assessment of gold and silver in assorted mobile phone printed circuit boards (PCBs). Waste Manag. 2015, 45, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.K.; Haque, N.; Somerville, M.; Pownceby, M.I.; Bhargava, S.; Tardio, J. Estimation of the generation and value recovery from e-waste printed circuit boards: Bangladesh case study. In REWAS 2022: Developing Tomorrow’s Technical Cycles; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2022; Volume I, pp. 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Debnath, B.; Chowdhury, R.; Ghosh, S.K. Sustainability of metal recovery from E-waste. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2018, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, A. Latest Global E-Waste Statistics and What They Tell Us. Roundup. 2024. Available online: https://theroundup.org/global-e-waste-statistics/ (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Verma, S.; Paul, A.R.; Haque, N. Selected environmental impact indicators assessment of wind energy in India using a life cycle assessment. Energies 2022, 15, 3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Gupta, A.; Verma, S.; Paul, A.R.; Jain, A.; Haque, N. Life cycle assessment based environmental footprint of a battery recycling process. In Intelligent Manufacturing and Energy Sustainability: Proceedings of ICIMES 2021; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Qadir, M.R.; Haque, N.; Chen, M.; Bruckard, W.J.; Pownceby, M.I. Formal and informal E-waste recycling methods for lithium-ion batteries: Advantages and disadvantages. In Global E-Waste Management Strategies and Future Implications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 73–104. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, S.; Paul, A.R.; Haque, N. Assessment of materials and rare earth metals demand for sustainable wind energy growth in India. Minerals 2022, 12, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthakur, A.; Govind, M. Computer and mobile phone waste in urban India: An analysis from the perspectives of public perception, consumption and disposal behaviour. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 717–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, D. E-waste projection using life-span and population statistics. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 1465–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wath, S.B.; Dutt, P.S.; Chakrabarti, T. E-waste scenario in India, its management and implications. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011, 172, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ari, V. A review of technology of metal recovery from electronic waste. In E-Waste in Transition—From Pollution to Resource; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2016; pp. 121–158. ISBN 978-953-51-2500-6. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.K.; Somerville, M.; Pownceby, M.I.; Tardio, J.; Haque, N.; Bhargava, S. Experimental Determination of Liquidus Temperature and Phase Equilibria of the CaO–Al2O3–SiO2–Na2O Slag System Relevant to E-Waste Smelting. In Rare Metal Technology 2021; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2021; pp. 265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Q.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Zeng, X. The life cycle assessment of an e-waste treatment enterprise in China. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2013, 15, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Gupta, A.; Verma, S.; Paul, A.R.; Jain, A.; Haque, N. Life cycle based greenhouse gas footprint assessment of a smartphone. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 795, p. 012028. [Google Scholar]

- He, P.; Feng, H.; Chhipi-Shrestha, G.; Hewage, K.; Sadiq, R. Life Cycle Assessment of e-Waste–Waste Cellphone Recycling. In Electronic Waste: Recycling and Reprocessing for a Sustainable Future; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2022; pp. 231–253. ISBN 9783527816392. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Williams, E.; Ju, M. Analysis of material and energy consumption of mobile phones in China. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 4135–4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adie, G.U.; Sun, L.; Zeng, X.; Zheng, L.; Osibanjo, O.; Li, J. Examining the evolution of metals utilized in printed circuit boards. Environ. Technol. 2017, 38, 1696–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holgersson, S.; Steenari, B.M.; Björkman, M.; Cullbrand, K. Analysis of the metal content of small-size Waste Electric and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) printed circuit boards—Part 1: Internet routers, mobile phones and smart phones. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 133, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Huda, N. E-waste in Australia: Generation estimation and untapped material recovery and revenue potential. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, M.; Shanmugam, P.V.; Mishra, A.; Mehendale, A.; Sherin, H.N. A multivariate discrete grey model for estimating the waste from mobile phones, televisions, and personal computers in India. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithya, R.; Sivasankari, C.; Thirunavukkarasu, A. Electronic waste generation, regulation and metal recovery: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 1347–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaashikaa, P.R.; Priyanka, B.; Kumar, P.S.; Karishma, S.; Jeevanantham, S.; Indraganti, S. A review on recent advancements in recovery of valuable and toxic metals from e-waste using bioleaching approach. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 132230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, H.; Rahman, T.U.; Suhan, M.B.K.; Al-Mamun, M.R.; Haque, S.; Islam, M.S. A comprehensive review on hazardous aspects and management strategies of electronic waste: Bangladesh perspectives. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaltonen, M.; Peng, C.; Wilson, B.P.; Lundström, M. Leaching of metals from spent lithium-ion batteries. Recycling 2017, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Kumar, P.; Saini, R. India’s Electronics Industry: Potential for Domestic Manufacturing and Exports. Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations-India Cellular and Electronics Association Publisher, New Delhi, India. 2021. Available online: https://icrier.org/pdf/India-Electronics-Industry_2021.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Brožová, S.; Lisińska, M.; Saternus, M.; Gajda, B.; Simha Martynková, G.; Slíva, A. Hydrometallurgical recycling process for mobile phone printed circuit boards using ozone. Metals 2021, 11, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASSOCHAM. Electricals & Electronics Manufaturing In India. ASSOCHAM NEC Technol. 2018. Available online: https://in.nec.com/en_IN/pdf/ElectricalsandElectronicsManufacturinginIndia2018.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Jha, M.K.; Kumari, A.; Jha, A.K.; Kumar, V.; Hait, J.; Pandey, B.D. Recovery of lithium and cobalt from waste lithium ion batteries of mobile phone. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 1890–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahan, M.; Kucuker, M.A.; Demirel, B.; Kuchta, K.; Hursthouse, A. Determination of metal content of waste mobile phones and estimation of their recovery potential in Turkey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S. Electronic Waste and India. Department of Information Technology Electronics Niketan, 6, C.G.O. Complex New Delhi-110 003, India. Available online: www.meity.gov.in/static/uploads/2024/03/EWaste_Sep11_892011.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Islam, M.K.; Haque, N.; Somerville, M.A. Characterisation and techno-economics of a process to recover value from e-waste materials. In TMS 2021 150th Annual Meeting & Exhibition Supplemental Proceedings; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2021; pp. 995–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, N.; Trivedi, A.; Hait, S. Material composition and associated toxicological impact assessment of mobile phones. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 104603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, R.K.; Nema, A.K. An analysis of preferences for hazardous substances free products: Manufacturing, use and end of life of mobile phones. Waste Manag. Res. 2012, 30, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zink, T.; Maker, F.; Geyer, R.; Amirtharajah, R.; Akella, V. Comparative life cycle assessment of smartphone reuse: Repurposing vs. refurbishment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2014, 19, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Zeng, X.; Li, J.; Duan, H.; Yuan, W. Environmental risk assessment of CRT and PCB workshops in a mobile e-waste recycling plant. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 12366–12373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarath, P.; Bonda, S.; Mohanty, S.; Nayak, S.K. Mobile phone waste management and recycling: Views and trends. Waste Manag. 2015, 46, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Duan, H.; Ogunseitan, O.A.; Li, J.; Tang, Y. Toxicity trends in E-Waste: A comparative analysis of metals in discarded mobile phones. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 380, 120898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Duan, H.; Yin, F.; Song, Q.; Li, J. Characterizing the materials composition and recovery potential from waste mobile phones: A comparative evaluation of cellular and smart phones. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 13016–13024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamalai, M.; Gurumurthy, K. Characterization of end-of-life mobile phone printed circuit boards for its elemental composition and beneficiation analysis. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2021, 71, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshta, N.; Patra, S.; Singh, S.P. Estimation of E-waste at micro level for reverse logistics: A case of Delhi. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 128063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, N.S.; Majhi, R. Disposal of obsolete mobile phones: A review on replacement, disposal methods, in-use lifespan, reuse and recycling. Waste Manag. Res. 2023, 41, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Switzer, J.; Marcano, G.; Kastner, R.; Pannuto, P. Junkyard computing: Repurposing discarded smartphones to minimize carbon. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 25–29 March 2023; Volume 2, pp. 400–412. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagat-Ganguly, V. E-Waste Management: Challenges and Opportunities in India; Routledge India: Delhi, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Turaga, R.M.R.; Bhaskar, K.; Sinha, S.; Hinchliffe, D.; Hemkhaus, M.; Arora, R.; Chatterjee, S.; Khetriwal, D.S.; Radulovic, V.; Singhal, P.; et al. E-Waste Management in India: Issues and Strategies. Vikalpa 2019, 44, 127–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manish, A.; Chakraborty, P. E-Waste Management in India: Challenges and Opportunities. Energy Resour. Inst. 2019. Available online: https://www.teriin.org/article/e-waste-management-india-challenges-and-opportunities (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Biswas, A.; Singh, S.G.; Singh, S.G. E-Waste Management in India: Challenges and Agenda. Cent. Sci. Environ. 2020, pp. 1–58. Available online: https://www.cseindia.org/e-waste-management-in-india-10593 (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Qadir, M.R.; Chen, M.; Haque, N.; Bruckard, W. Estimated End-of-Life Lithium-Ion Battery Resources for Potential Recycling in Bangladesh. In TMS Annual Meeting & Exhibition; Springer Nature: Cham, Germany, 2023; pp. 161–174. [Google Scholar]

- Mairizal, A.Q.; Sembada, A.Y.; Tse, K.M.; Rhamdhani, M.A. Electronic waste generation, economic values, distribution map, and possible recycling system in Indonesia. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golev, A.; Corder, G.D.; Rhamdhani, M.A. Estimating flows and metal recovery values of waste printed circuit boards in Australian e-waste. Miner. Eng. 2019, 137, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K. The diffusion of mobile phones in India. Telecommun. Policy 2008, 32, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forti, V.; Baldé, K.; Kuehr, R. E-Waste Statistics: Guidelines on Classifications, Reporting and Indicators; United Nations University, ViE—SCYCLE: Bonn, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-92-808-9066-2. [Google Scholar]

- ICAI. Available online: https://www.icai.org/ (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Index Mundi. Available online: https://www.indexmundi.com/ (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Keeley, B.; Love, P. From crisis to recovery. In OECD Insights; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2010; pp. 1–147. ISBN 978-92-64-06911-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.S.; Lee, J.C.; Jeong, J.; Yang, D.H.; Shin, D.; Lee, K.I. A novel process for extracting precious metals from spent mobile phone PCBs and automobile catalysts. Mater. Trans. 2013, 54, 1045–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, R.; Jha, M.K.; Lee, J.C.; Pathak, D.D. Developed commercial processes to recover au, ag, Pt, and Pd from E-waste. In Rare Metal Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2021; pp. 115–126. [Google Scholar]

| Country | E-Waste Produced (Mt) | Recycled Volume (Mt) | Recycled (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | 10,129 | 1620.64 | 16 |

| USA | 6918 | 1037.7 | 15 |

| India | 3230 | 32.3 | 1 |

| Japan | 2569 | 565.18 | 22 |

| Brazil | 2143 | 2143 | 100 |

| Russia | 1631 | 97.86 | 6 |

| Indonesia | 1618 | 48.54 | 3 |

| Germany | 1607 | 835.64 | 52 |

| UK | 1598 | 910.86 | 57 |

| France | 1362 | 762.72 | 56 |

| Metal | PCB (Concentration in g/kg) | Display (Concentration in g/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| Ag | 3.60 ± 2.00 | 0.410 ± 0.190 |

| Au | 1.40 ± 0.750 | 0.102 ± 0.088 |

| Pd | 0.290 ± 0.230 | 0.081 ± 0.011 |

| Pt | 0.030 ± 0.010 | 0.470 ± 0.180 |

| Cu | 335 ± 74.0 | 14.3 ± 0.750 |

| Fe | 23.2 ± 15.2 | 2.50 ± 1.10 |

| Al | 14.1 ± 3.50 | 7.90 ± 4.10 |

| Sn | 31.6 ± 13.5 | 0.975 ± 0.012 |

| Ni | 25.0 ± 13.1 | 1.55 ± 0.150 |

| Zn | 19.2 ± 17.3 | 0.770 ± 0.460 |

| Cr | 1.70 ± 4.10 | 1.99 ± 2.57 |

| Pb | 12.0 ± 8.70 | 0.295 ± 0.114 |

| Si | 18.8 ± 2.20 | 18.8 ± 1.25 |

| Li | 0.442 ± 0.221 | 0.321 ± 0.125 |

| Co | 0.210 ± 0.180 | 0.130 ± 0.020 |

| La | 0.340 ± 0.140 | 0.210 ± 0.012 |

| Ce | 0.067 ± 0.047 | 0.016 ± 0.058 |

| Year | Ag | Au | Pd | Pt | Cu | Al | Sn | Ni | Zn | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 66.13 | 1296.89 | 525.01 | 24.69 | 57.53 | 0.60 | 18.14 | 9.09 | 1.11 | 0.51 |

| 2023 | 69.41 | 1374.12 | 525.72 | 25.56 | 59.87 | 0.63 | 17.55 | 9.37 | 1.17 | 0.53 |

| 2024 | 79.23 | 1477.99 | 573.24 | 29.49 | 68.54 | 0.72 | 21.59 | 10.12 | 1.33 | 0.61 |

| 2025 | 81.36 | 1736.96 | 553.23 | 29.53 | 69.06 | 0.72 | 24.07 | 9.61 | 1.33 | 0.61 |

| 2026 | 85.08 | 1840.56 | 557.10 | 31.38 | 73.72 | 0.77 | 27.60 | 9.86 | 1.41 | 0.65 |

| 2027 | 91.72 | 1907.87 | 564.67 | 33.06 | 78.13 | 0.80 | 31.68 | 10.23 | 1.47 | 0.68 |

| 2028 | 100.59 | 2017.22 | 614.22 | 36.26 | 85.83 | 0.89 | 31.09 | 10.88 | 1.65 | 0.76 |

| 2029 | 104.20 | 2148.87 | 617.90 | 37.65 | 89.08 | 0.92 | 35.13 | 10.93 | 1.70 | 0.78 |

| 2030 | 107.54 | 2284.02 | 622.15 | 39.05 | 92.39 | 0.95 | 37.62 | 10.96 | 1.76 | 0.81 |

| 2031 | 110.82 | 2486.06 | 622.86 | 39.91 | 94.73 | 0.98 | 41.14 | 11.24 | 1.82 | 0.82 |

| 2032 | 120.64 | 2563.29 | 670.37 | 43.84 | 103.40 | 1.07 | 45.23 | 11.99 | 1.97 | 0.91 |

| 2033 | 122.77 | 2667.16 | 650.36 | 43.88 | 103.92 | 1.07 | 44.63 | 11.48 | 1.98 | 0.91 |

| 2034 | 126.49 | 2926.14 | 654.23 | 45.74 | 108.58 | 1.12 | 48.67 | 11.73 | 2.06 | 0.95 |

| 2035 | 133.13 | 3029.73 | 661.81 | 47.42 | 112.98 | 1.15 | 51.16 | 12.09 | 2.12 | 0.98 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jaiswal, P.; Verma, S.; Paul, A.R.; Haque, N.; Bruckard, W. Economic Valuation of Metal Recovery from Mobile Phones in India. Minerals 2025, 15, 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030259

Jaiswal P, Verma S, Paul AR, Haque N, Bruckard W. Economic Valuation of Metal Recovery from Mobile Phones in India. Minerals. 2025; 15(3):259. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030259

Chicago/Turabian StyleJaiswal, Pushkal, Shalini Verma, Akshoy Ranjan Paul, Nawshad Haque, and Warren Bruckard. 2025. "Economic Valuation of Metal Recovery from Mobile Phones in India" Minerals 15, no. 3: 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030259

APA StyleJaiswal, P., Verma, S., Paul, A. R., Haque, N., & Bruckard, W. (2025). Economic Valuation of Metal Recovery from Mobile Phones in India. Minerals, 15(3), 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030259