Naturally Occurring Asbestos (NOA) in Granitoid Rocks, A Case Study from Sardinia (Italy)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

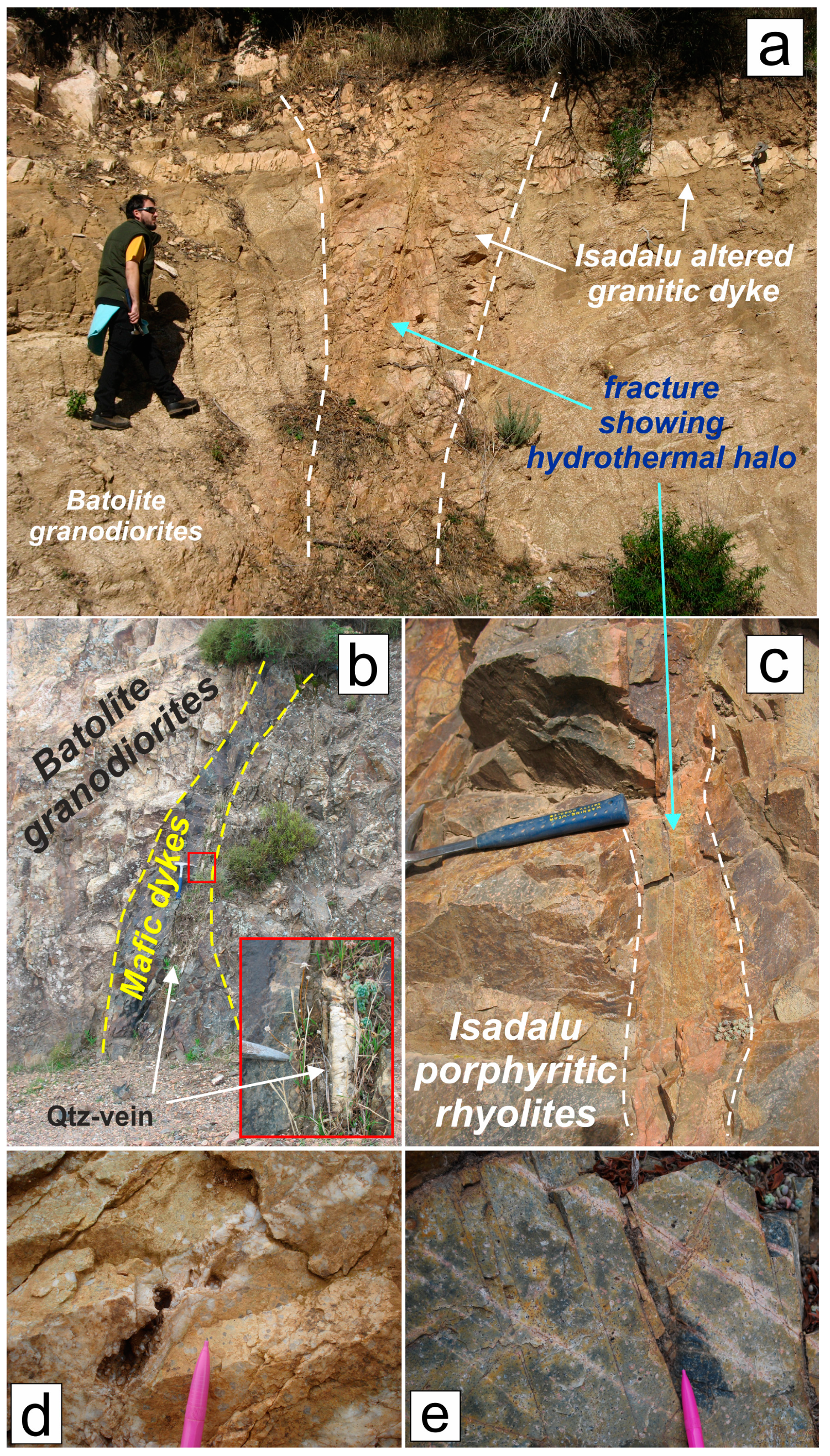

2. Geological Setting

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

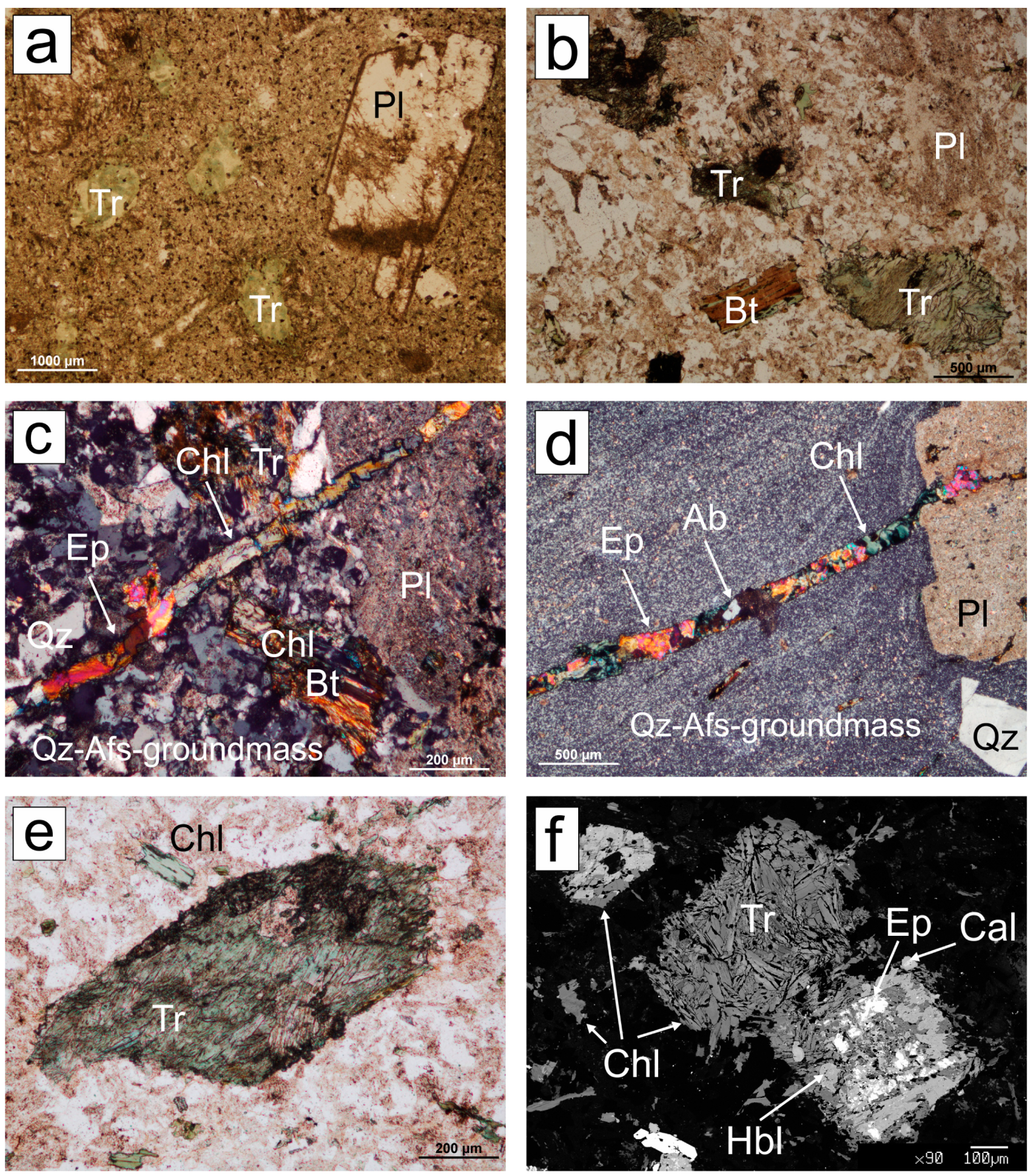

4.1. Petrography

4.1.1. Primary Magmatic Fabric

4.1.2. Secondary Fabric

4.1.3. Secondary Amphibole Morphology

4.2. Mineral Chemistry

4.2.1. Feldspar

4.2.2. Epidote

4.2.3. Chlorite

4.2.4. Amphibole

5. Thermobarometric Estimates

6. Discussion

6.1. Genesis of Actinolite-Tremolite

6.2. From Fibers to Mountains: A Matter of Hazard

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gunter, M.E.; Belluso, E.; Mottana, A. Amphiboles: Environmental and health concerns. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2007, 67, 453–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignaroli, G.; Rossetti, F.; Belardi, G.; Billi, A. Linking rock fabric to fibrous mineralisation: A basic tool for the asbestos hazard. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 11, 1267–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vignaroli, G.; Ballirano, P.; Belardi, G.; Rossetti, F. Asbestos fibre identification vs. evaluation of asbestos hazard in ophiolitic rock mélanges, a case study from the Ligurian Alps (Italy). Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 72, 3679–3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.F. Amphiboles in the igneous environment. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2007, 67, 323–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, P.S.; Trout, D.; Zumwalde, R.D. Asbestos fibers and other elongate mineral particles: State of the science and roadmap for research. In Current Intelligence Bullettin; NIOSH: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2011; Volume 62. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/5892 (accessed on 6 October 2018).

- Gunter, M.E. Defining asbestos: Differences between the built and natural environments. Chimia 2010, 64, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Asbestos and Other Natural Mineral Fibres: Environmental Health Criteria 53. Available online: http://www.inchem.org/documents/ehc/ehc/ehc53.htm (accessed on 6 October 2018).

- Ross, M.; Kuntze, R.A.; Clifton, R.A. A definition for asbestos. In Definitions for Asbestos and Other Health-Related Silicates; Levadie, B., Ed.; American Society for Testing and Materials: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1984; pp. 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Levadie, B. Definitions for Asbestos and Other Health-Related Silicates: A Symposium (No. 834); American Society for Testing and Materials: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.J.; Strohmeier, B.R.; Bunker, K.L.; Van Orden, D.R. Naturally occurring asbestos—A recurring public policy challenge. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 153, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreier, H. Asbestos in the Natural Environment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, J.H.; Lange, P.R.; Reinhard, T.K.; Thomulka, K.W. A study of personal and area airborne asbestos concentrations during asbestos abatement: A statistical evaluation of fibre concentration data. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 1996, 40, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakrzewska, A.M.; Capone, P.P.; Iannò, A.; Tarzia, V.; Campopiano, A.; Villella, E.; Giardino, R. Calabrian ophiolites: Dispersion of airborne asbestos fibers during mining and milling operations. Period. Mineral. 2008, 77, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Burilkov, T.; Michailova, L. Asbestos content of the soil and endemic pleural asbestosis. Environ. Res. 1970, 3, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, R.J.; Highsmith, V.R.; Costa, D.L.; Krewer, J.A. Indoor asbestos concentrations associated with the use of asbestos-contaminated tap water in portable home humidifiers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1992, 26, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanouil, K.; Kalliopi, A.; Dimitrios, K.; Evangelos, G. Asbestos pollution in an inactive mine: Determination of asbestos fibers in the deposit tailings and water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 167, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar]

- Gualtieri, A.F.; Pollastri, S.; Gandolfi, N.B.; Ronchetti, F.; Albonico, C.; Cavallo, A.; Zanetti, G.; Marini, P.; Sala, O. Determination of the concentration of asbestos minerals in highly contaminated mine tailings: An example from inactive mine waste of Cre’taz and E’marese (Valle d’Aosta, Italy). Am. Mineral. 2014, 99, 1233–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloise, A.; Punturo, R.; Catalano, M.; Miriello, D.; Cirrincione, R. Naturally occurring asbestos (NOA) in rock and soil and relation with human activities: The monitoring example of selected sites in Calabria (southern Italy). Ital. J. Geosci. 2016, 135, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellopede, R.; Clerici, C.; Marini, P.; Zanetti, G. Rocks with asbestos: Risk evaluation by means of an abrasion test. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 2009, 5, 500–506. [Google Scholar]

- Giacomini, F.; Boerio, V.; Polattini, S.; Tiepolo, M.; Tribuzio, R.; Zanetti, A. Evaluating asbestos fibre concentration in metaophiolites: A case study from the Voltri Massif and Sestri–Voltaggio Zone (Liguria; NW Italy). Environ. Earth Sci. 2010, 61, 1621–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescano, L.; Marfil, S.; Maiza, P.; Sfragulla, J.; Bonalumi, A. Amphibole in vermiculite mined in Argentina. Morphology; quantitative and chemical studies on the different phases of production and their environmental impact. Environ. Earth. Sci. 2013, 70, 1809–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, J.C. Metamorphic amphiboles: Composition and coexistence. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2007, 67, 359–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, M.; Nolan, R.P. History of asbestos discovery and use and asbestos-related disease in context with the occurrence of asbestos within ophiolite complexes. Geol. Soc. Am. 2003, 373, 447–470. [Google Scholar]

- Compagnoni, R.; Groppo, C. Gli amianti in Val di Susa e le rocce che li contengono. Rend. Soc. Geol. Ital. 2006, 3, 21–28. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Van Gosen, B.S. The geology of asbestos in the United States and its practical applications. Environ. Eng. Geosci. 2007, 13, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickx, M. Naturally occurring asbestos in eastern Australia: A review of geological occurrence; disturbance and mesothelioma risk. Environ. Geol. 2009, 57, 909–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianfagna, A.; Ballirano, P.; Bellatreccia, F.; Bruni, B.; Paoletti, L.; Oberti, R. Characterization of amphibole fibres linked to mesothelioma in the area of Biancavilla, Eastern Sicily, Italy. Mineral. Mag. 2003, 67, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strating, E.H.H.; Vissers, R.L. Structures in natural serpentinite gouges. J. Struct. Geol. 1994, 16, 1205–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissers, R.L.M.; Drury, M.R.; Hoogerduijn, E.H.; Spiers, C.J.; Van der Wal, D. Mantle shear zones and their effect on lithosphere strength during continental breakup. Tectonophysics 1995, 249, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scambelluri, M.; Müntener, O.; Hermann, J.; Piccardo, G.B.; Trommsdorff, V. Subduction of water into the mantle: History of an Alpine peridotite. Geology 1995, 23, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, J.; Müntener, O.; Scambelluri, M. The importance of serpentinite mylonites for subduction and exhumation of oceanic crust. Tectonophysics 2000, 327, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.D.; Selverstone, J.; Sharp, Z.D. Interactions between serpentinite devolatilization, metasomatism and strike-slip strain localization during deep-crustal shearing in the Eastern Alps. J. Metamorph. Geol. 2004, 22, 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.P.; Rahn, M.; Bucher, K. Serpentinites of the Zermatt-Saas ophiolite complex and their texture evolution. J. Metamorph. Geol. 2004, 22, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edel, J.B.; Montigny, R.; Thuizat, R. Late Paleozoic rotations of Corsica and Sardinia: New evidence from paleomagnetic and K-Ar studies. Tectonophysics 1981, 79, 201–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traversa, G.; Ronca, S.; Del Moro, A.; Pasquali, C.; Buraglini, N.; Barabino, G. Late to post-Hercynian dyke activity in the Sardinia-Corsica domain: A transition from orogenic calc-alkaline to anorogenic alkaline magmatism. Boll. Soc. Geol. Ital. 2003, 2, 131–152. [Google Scholar]

- Edel, J.B. Hypothèse d’une ample rotation horaire tardi-varisque du bloc Maures-Estérel-Corse-Sardaigne. Géol. Fr. 2000, 1, 3–19. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Atzori, P.; Cirrincione, R.; Del Moro, A.; Mazzoleni, P. Petrogenesis of late Hercynian calc-alkaline dykes of mid-eastern Sardinia: Petrographical and geochemical data constraining hybridization process. Eur. J. Mineral. 2000, 12, 1261–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortesogno, L.; Cassinis, G.; Dallagiovanna, G.; Gaggero, L.; Oggiano, G.; Ronchi, A.; Seno, S.; Vanossi, M. The Variscan post-collisional volcanism in late Carboniferous–Permian sequences of Ligurian Alps, Southern Alps and Sardinia (Italy): A synthesis. Lithos 1998, 45, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmignani, L.; Carosi, R.; Di Pisa, A.; Gattiglio, M.; Musumeci, G.; Oggiano, G.; Pertusati, P. The hercynian chain in Sardinia (Italy). Geodin. Acta 1994, 7, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmignani, L.; Rossi, P.; Barca, S.; Oggiano, G.; Duran Delga, M.; Salvadori, I.; Conti, P.; Eltrudis, A.; Funedda, A.L.; Pasci, G. Carta Geologico-Strutturale della Sardegna e della Corsica (Scala 1:500.000); BRGM: Orléans, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dini, A.; Di Vincenzo, G.; Ruggieri, G.; Rayner, J.; Lattanzi, P. Monte Ollasteddu, a new gold discovery in the Variscan basement of Sardinia (Italy): First isotopic (40Ar-39Ar, Pb) and fluid inclusion data. Miner. Depos. 2005, 40, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, G.; Ricci, C.; Rita, F. Isotopic ages and tectono-metamorphic history of the metamorphic basement of north-eastern Sardinia. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1978, 68, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, J.P. Dynamics of orogenic wedges and the uplift of high-pressure metamorphic rocks. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1986, 97, 1037–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elter, F.M.; Faure, M.; Ghezzo, C.; Corsi, B. Les zones de cisaillement tardi-hercyniennes en Sardaigne du Nord-Est (Italie). Geol. Fr. 1999, 2, 3–16. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Cassinis, G.; Ronchi, A. The (late-) post-Variscan continental succession of Sardinia. Rend. Soc. Paleontol. Ital. 2002, 1, 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Di Vincenzo, G.; Andriessen, P.A.; Ghezzo, C. Evidence of two different components in a Hercynian peraluminous cordierite-bearing granite: The San Basilio intrusion (central Sardinia; Italy). J. Petrol. 1996, 37, 1175–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccaluva, L.; Civetta, L.; Macciotta, G.; Ricci, C.A. Geochronology in Sardinia: Results and problems. Rend. Soc. Ital. Min. Petr. 1985, 40, 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ghezzo, C.; Orsini, J.B. Lineamenti strutturali e composizionali del batolite ercinico sardo-corso in Sardegna. In Guida alla Geologia del Paleozoico Sardo, Guide Geologiche Regionali; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1982; pp. 88–102. [Google Scholar]

- Di Vincenzo, G.; Elter, F.M.; Ghezzo, C.; Palmeri, R.; Ricci, C.A. Petrological evolution of the Palaeozoic basement of Sardinia. In Petrology, Geology and Ore Deposits of the Palaezoic Basement of Sardinia; Guide-book to the Field Excursion (B3), Proceedings of the 16th General Meeting of the IMA (4–9 September 1994); Ente Minerario Sardo: Cagliari, Italy, 1994; pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Vaccaro, C.; Atzori, P.; Del Moro, A.; Oddone, M.; Traversa, G.; Villa, I.M. Geochronology and Sr-isotope geochemistry of late Hercynian dykes from Sardinia. Schweiz. Miner. Petrog. 1991, 71, 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Bralia, A.; Ghezzo, C.; Guasparri, G.; Sabatini, G. Aspetti genetici del batolite sardo-corso. Rend. Soc. Ital. Min. Petr. 1982, 38, 701–764. [Google Scholar]

- Ronca, S.; Traversa, G. Late-Hercynian dyke magmatism of Sarrabus (SE Sardinia). Period. Mineral. 1996, 65, 35–70. [Google Scholar]

- Del Moro, A.; Di Simplicio, P.; Ghezzo, C.; Guasparri, G.; Rita, F.; Sabatini, G. Radiometric data and intrusive sequence in the Sardinian batholith. Neues Jahrb. Mineral. Abh. 1975, 126, 28–44. [Google Scholar]

- Atzori, P.; Traversa, G. Post-granitic permo-triassic dyke magmatism in eastern Sardinia (Sarrabus, Barbagia, Mandrolisai, Goceano, Baronie and Gallura). Period. Mineral. 1986, 55, 203–231. [Google Scholar]

- Carmignani, L.; Cherchi, G.P.; Del Moro, A.; Franceschelli, M.; Ghezzo, C.; Musumeci, G.; Pertusati, P.C. The mylonitic granitoids and tectonic units of the Mount Grighini Complex (W-Sardinia): A preliminary note. In Correlation of Prevariscan and Variscan Events of the Alpine-Mediterranean Mountain Belt; IGCP project No. 5, Newsletter; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1987; pp. 25–26. [Google Scholar]

- Del Moro, A.; Laurenzi, M.; Musumeci, G.; Pardini, G. Geochimica isotopica dello Sr e geocronologia sul complesso intrusivo ercinico del Monte Grighini, Sardegna centro-occidentale. In Proceedings of the Società Italiana di Mineralogia e Petrologia Meeting, Ischia, Italy, 15–18 October 1990. (In Italian). [Google Scholar]

- Traversa, G. Sulla giacitura ed età di alcuni filoni basici nelle vulcaniti ignimbritiche permiane della Gallura (Sardegna settentrionale). Rend. Soc. Ital. Min. Petr. 1969, 25, 149–155. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Carmignani, L.; Cherchi, A.; Ricci, C.A. Basement structure and Mesozoic-Cenozoic evolution of Sardinia. In The Lithosphere in Italy; Boriani, A., Bonafede, M., Piccardo, G.B., Vai, G.B., Eds.; Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei: Roma, Italy, 1989; pp. 63–92. [Google Scholar]

- Baldelli, C.; Bigazzi, G.; Elter, F.M.; Macera, P. Description of a permo-trias alkaline lamprophyre embedded into the micaschists of garnet-staurolite-kyanite grade north-eastern Sardinia Island. In Proceedings of the Paleozoic, Stratigraphy, Tectonics, Metamorphism and Magmatism in Italy, Siena, Italy, 13–14 December 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Vaccaro, C.; Traversa, G. REE Distribution in Late Hercynian Dykes from Sardinia; IGCP N.276, Newsletter; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1992; Volume 5, pp. 215–226. [Google Scholar]

- Traversa, G.; Ronca, S.; Pasquali, C. Post-Hercynian basic dyke magmatism of the Concas-Alà dei Sardi alignment (Northern Sardinia-Italy). Period. Mineral. 1997, 66, 233–262. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzupoli, D.; Discendenti, A.; Lombardi, G.; Nicoletti, M. Cronologia K-Ar delle manifestazioni eruttive del settore di Seui-Seulo (Barbagia-Sardegna). Period. Mineral. 1971, 40, 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Gaggero Sager, L.M.; Cassinis, G.; Cortesogno, L.; Ronchi, A.; Valloni, R. Stratigraphic and Petrographic investigations into the Permian-Triassic continental sequences of Nurra (NWSardinia). J. Iber. Geol. 1996, 21, 149–170. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi, G.; Cozzupoli, D.; Nicoletti, M. Notizie geopetrografiche e dati sulla cronologia K-Ar del vulcanismo tardopaleozoico sardo. Period. Mineral. 1974, 43, 221–312. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, L.; Maccioni, L.; Pili, P. Sardegna Scala 1:25.000—Carta Geopetrografica dell'alto Flumendosa (Villanova Strisaili); Istituto di Mineralogia e Petrografia, Università di Cagliari; Istituto di Petrografia, Università di Roma—col.-S.E.L.C.A.: Firenze, Italy, 1981; Nº inv. 800; Available online: http://www.geologi.sardegna.it/documenti/cartografia-geologica/ (accessed on 6 October 2018). (In Italian)

- Zaccaria, B. Saggio di Petrografia: Caratterizzazione Petrografica delle Magmatiti del Mt. Isadalu (Villagrande Strisaili—Ogliastra, Sardegna). In Tesi Triennale (Unpublished B.S. Thesis); Cozzupoli, D., Lucci, F., Eds.; Università degli studi Roma Tre: Roma, Italy, 2010. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Lucci, F.; White, J.; Cozzupoli, D.; Traversa, G.; Zaccaria, B. Mt. Isadalu Complex (Sardinia, Italy): An example of post-hercynian transition from High-K calcalkaline to Shoshonitic/Low-K alkaline magmatism. In Proceedings of the Poster presentation at PERALK-CARB Congress, Tuebingen, Germany, 15–16 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lucci, F.; White, J.; Campagnola, S. Cpx-Hbl Thermobarometry of Igneous Mafic Rock: Possible History of Permian Andesitic Dyke at Mt. Isadalu Complex (Sardinia, Italy). Poster Presentation at Rittmann Congress 2012. Available online: Https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235347522_Cpx-Hbl_thermobarometry_of_igneous_mafic_rock_possible_history_of_Permian_andesitic_dyke_at_Mt_Isadalu_Complex_Sardinia_Italy (accessed on 6 October 2018).

- Tröger, W.E. Optical Determination of Rock-forming Minerals—Part 1 Determinative Tables; English Edition of the Fourth German Edition; Bambauer, H.U., Taborzsky, F., Trochim, H.D., Eds.; E. Schweizerbart’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung (Nägele u. Obermiller): Stuttgart, Germany, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brandelik, A. CALCMIN—An EXCEL™ Visual Basic application for calculating mineral structural formulae from electron microprobe analyses. Comput. Geosci. 2009, 35, 1540–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, O.; Parra, T.; Vieillard, P. Thermodynamic properties of the Tschermak solid solution in Fe-chlorite: Application to natural examples and possible role of oxidation. Am. Mineral. 2005, 90, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locock, A.J. An Excel spreadsheet to classify chemical analyses of amphiboles following the IMA 2012 recommendations. Comput. Geosci. 2014, 62, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, D.L.; Evans, B.W. Abbreviations for names of rock-forming minerals. Am. Mineral. 2010, 95, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Maitre, R.W.; Streckeisen, A.; Zanettin, B.; Le Bas, M.J.; Bonin, B.; Bateman, P.; Bellieni, G.; Dudek, A.; Efremova, S.; Keller, J.; et al. Igneous Rocks: A Classification and Glossary of Terms. Recommendations of the IUGS Subcomission on the Systematics of Igneous Rocks; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Streckeisen, A.L. Plutonic rock: Classification and nomenclature recommended by the IUGS Subcommission on the Systematics of Igneous Rocks. Geotimes 1973, 18, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streckeisen, A. Classification and nomenclature of volcanic rocks, lamprophyres, carbonatites, and melilitic rocks: Recommendations and suggestions of the IUGS Subcommission on the Systematics of Igneous Rocks. Geology 1979, 7, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streckeisen, A. To each plutonic rock its proper name. Earth Sci. Rev. 1976, 12, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shand, S.J. Eruptive Rocks; Murby: London, UK, 1927; p. 360. [Google Scholar]

- Shand, S.J. Eruptive Rocks: Their Genesis, Composition, Classification, and Their Relation to Ore Deposits with a Chapter on Meteorites; Murby: London, UK, 1943. [Google Scholar]

- Shand, S.J. The Study of Rocks, 2nd ed.; Murby: London, UK, 1947; p. 236. [Google Scholar]

- Millette, J.R. Asbestos analysis methods. In Asbestos: Risk Assessment, Epidemiology, and Health Effects; CRC Press: Abingdon, UK, 2006; pp. 9–38. [Google Scholar]

- Millette, J.R.; Bandli, B.R. Asbestos identification using available standard methods. Microscope 2005, 53, 179. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, M.; Lee, E.G.; Doorn, S.S.; Hammond, O. Differentiating non-asbestiform amphibole and amphibole asbestos by size characteristics. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2008, 5, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatfield, E.J. A procedure for quantitative description of fibrosity in amphibole minerals. In Proceedings of the 2008 ASTM Johnson Conference: Critical Issues in Monitoring Asbestos, Burlington, VT, USA, 14–18 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, F.; Nozaem, R.; Lucci, F.; Vignaroli, G.; Gerdes, A.; Nasrabadi, M.; Theye, T. Tectonic setting and geochronology of the Cadomian (Ediacaran-Cambrian) magmatism in central Iran, Kuh-e-Sarhangi region (NW Lut Block). J. Asian Earth Sci. 2015, 102, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, H.S.; Rossetti, F.; Lucci, F.; Chiaradia, M.; Gerdes, A.; Martinez, M.L.; Ghorbani, G.; Nasrabady, M. The calc-alkaline and adakitic volcanism of the Sabzevar structural zone (NE Iran): Implications for the Eocene magmatic flare-up in Central Iran. Lithos 2016, 248, 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.W.; Poli, S. Magmatic epidote. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2004, 56, 399–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawthorne, F.C.; Oberti, R.; Harlow, G.E.; Maresch, W.V.; Martin, R.F.; Schumacher, J.C.; Welch, M.D. Nomenclature of the amphibole supergroup. Am. Mineral. 2012, 97, 2031–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leake, B.E.; Woolley, A.R.; Arps, C.E.; Birch, W.D.; Gilbert, M.C.; Grice, J.D.; Hawthorne, F.C.; Kato, A.; Kisch, H.J.; Krivovichev, V.G.; et al. Nomenclature of amphiboles: Report of the subcommittee on amphiboles of the international mineralogical association commission on new minerals and mineral names. Mineral. Mag. 1997, 61, 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leake, B.E.; Woolley, A.R.; Birch, W.D.; Burke, E.A.; Ferraris, G.; Grice, J.D.; Hawthorne, F.C.; Kisch, H.J.; Krivovichev, V.G.; Schumacher, J.C.; et al. Nomenclature of amphiboles: Additions and revisions to the International Mineralogical Association’s amphibole nomenclature. Mineral. Mag. 2004, 68, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, K.R. User’s Manual for Isoplot 3.00: A Geochronological Toolkit for Microsoft Excel; Berkeley Geochronology Center: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Calzolari, G.; Rossetti, F.; Ault, A.K.; Lucci, F.; Olivetti, V.; Nozaem, R. Hematite (U-Th)/He thermochronometry constrains intraplate strike-slip faulting on the Kuh-e-Faghan Fault; central Iran. Tectonophysics 2018, 728, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.L. Status of thermobarometry in granitic batholiths. Earth Environ. Sci. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 1996, 87, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.L.; Smith, D.R. The effects of temperature and fO₂ on the Al-in-hornblende barometer. Am. Mineral. 1995, 80, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.W. Amphibole composition in tonalite as a function of pressure: An experimental calibration of the Al-in-hornblende barometer. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1992, 110, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.L.; Barth, A.P.; Wooden, J.L.; Mazdab, F. Thermometers and thermobarometers in granitic systems. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2008, 69, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutch, E.J.F.; Blundy, J.D.; Tattitch, B.C.; Cooper, F.J.; Brooker, R.A. An experimental study of amphibole stability in low-pressure granitic magmas and a revised Al-in-hornblende geobarometer. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2016, 171, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, T.; Blundy, J. Non-ideal interactions in calcic amphiboles and their bearing on amphibole-plagioclase thermometry. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1994, 116, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cathelineau, M. Cation site occupancy in chlorites and illites as function of temperature. Clay Min. 1988, 23, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, F.; Asti, R.; Faccenna, C.; Gerdes, A.; Lucci, F.; Theye, T. Magmatism and crustal extension: Constraining activation of the ductile shearing along the Gediz detachment; Menderes Massif (Western Turkey). Lithos 2017, 282, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorpi, M.J.; Coulon, C.; Orsini, J.B. Hybridization between felsic and mafic magmas in calc-alkaline granitoids—A case study in northern Sardinia, Italy. Chem. Geol. 1991, 92, 45–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, B.W. Metamorphism of alpine peridotite and serpentinite. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1977, 5, 397–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, I.; Barnicoat, A.C. Geochemical and stable isotope resetting in shear zones from Täschalp: Constraints on fluid flow during exhumation in the Western Alps. J. Metamorph. Geol. 2003, 21, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, D.R.; Gregory, R.T. Ophiolite obduction and the Samail Ophiolite: The behaviour of the underlying margin. In Geological Society, London, Special Publications (2003); Geological Society of London: London, UK, 2003; Volume 218, pp. 449–465. [Google Scholar]

- Dilles, J.H.; Einaudi, M.T. Wall-rock alteration and hydrothermal flow paths about the Ann-Mason porphyry copper deposit, Nevada; a 6-km vertical reconstruction. Econ. Geol. 1992, 87, 1963–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battles, D.A.; Barton, M.D. Arc-related sodic hydrothermal alteration in the western United States. Geology 1995, 23, 913–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.A.; Barton, M.D.; Hassanzadeh, J. Mafic and felsic hosted Fe-apatite-(REE-Cu) mineralization in Nevada. In Abstracts with Programs—Geological Society of America; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 1993; Volume 25, p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Carten, R.B. Sodium-calcium metasomatism, chemical, temporal, and spatial relationships at the Yerington, Nevada; porphyry copper deposit. Econ. Geol. 1986, 81, 1495–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijland, T.G.; Touret, J.L. Replacement of graphic pegmatite by graphic albite-actinolite-clinopyroxene intergrowths (Mjavatn, southern Norway). Eur. J. Mineral. 2001, 13, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, G.; Foster, D.R.W. Magmatic–hydrothermal albite–actinolite–apatite-rich rocks from the Cloncurry district, NW Queensland, Australia. Lithos 2000, 51, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, G.; De Jong, G. Synchronous granitoid emplacement and episodic sodic-calcific alteration in the Cloncurry district: Styles, timing and metallogenic significance. In New Developments in Metallogenic Research: The McArthur, Mt Isa, Cloncurry Minerals Province; Baker, T., Rotherham, J., Richmond, J., Mark, G., Williams, P.J., Eds.; James Cook University of North Queensland, Economic Geology Research Unit Contribution: Townsville, Australia, 1996; Volume 5, pp. 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ridley, J. Ore Deposit Geology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Di Ciaula, A.; Gennaro, V. Rischio clinico da ingestione di fibre di amianto in acqua potabile. Epidemiol. Prev. 2016, 40, 472–475. (In Italian) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Capuano, F.; Fava, A.; Bacci, T.; Sala, O.; Paoli, F.; Biancolini, V.; Motta, E. La ricerca di amianto nelle acque potabili. Ecoscienza 2014, 3, 54–55. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

| Rock | Andesite | Granitoid | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | FP-FPSC | VG-VGFR | ||||||

| Type | Primary | Secondary | Primary | Secondary | ||||

| Spot | #72 | #62 | #26 | #42 | #102 | #46 | #109 | #138 |

| SiO2 (wt%) | 48.21 | 54.41 | 66.67 | 66.04 | 66.34 | 64.73 | 68.75 | 67.86 |

| Al2O3 | 30.96 | 27.36 | 17.48 | 20.40 | 17.54 | 17.44 | 15.17 | 19.29 |

| FeOtot | 0.45 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.14 |

| CaO | 16.02 | 10.65 | 0.00 | 2.13 | 3.55 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 1.49 |

| Na2O | 2.42 | 6.06 | 0.80 | 11.66 | 11.15 | 0.97 | 11.75 | 11.58 |

| K2O | 0.11 | 0.31 | 15.82 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 16.07 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Total | 98.17 | 99.00 | 100.99 | 100.55 | 98.82 | 99.35 | 98.04 | 100.46 |

| Si (apfu) | 2.25 | 2.49 | 3.04 | 2.90 | 2.97 | 3.02 | 3.08 | 2.97 |

| Al | 1.70 | 1.47 | 0.94 | 1.06 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.80 | 0.99 |

| Fe3+ | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Ca | 0.80 | 0.52 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| Na | 0.22 | 0.54 | 0.07 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.09 | 1.02 | 0.98 |

| K | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.92 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.96 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| An (%) (a) | 78% | 48% | - | 9% | 15% | - | 8% | 6% |

| Ab (%) (a) | 21% | 50% | 7% | 90% | 84% | 8% | 91% | 93% |

| Or (%) (a) | 1% | 2% | 93% | 1% | 1% | 92% | 1% | 1% |

| Rock | Andesite | Granitoid | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | FP-FPSC | VG-VGFR | ||||||

| Type | Primary | Secondary | Primary | Secondary | ||||

| Spot | #19 | #18 | #164 | #21 | #106 | #108 | #82 | #88 |

| SiO2 (wt%) | 38.20 | 38.30 | 37.83 | 38.78 | 37.16 | 37.64 | 38.05 | 39.21 |

| TiO2 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.39 | 1.07 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| Al2O3 | 21.35 | 25.10 | 23.12 | 25.98 | 20.95 | 23.75 | 25.54 | 26.43 |

| FeOtot | 14.21 | 10.29 | 8.78 | 7.47 | 14.97 | 11.11 | 9.12 | 7.34 |

| MnO | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.45 | 0.07 | 0.55 | 0.18 | 0.40 | 0.32 |

| MgO | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| CaO | 22.92 | 23.38 | 22.65 | 23.42 | 22.59 | 23.26 | 24.21 | 24.22 |

| Na2O | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| K2O | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Total | 97.27 | 97.70 | 93.01 | 95.85 | 96.87 | 97.15 | 97.46 | 97.63 |

| Formula (12.5 oxygens) | ||||||||

| Si (apfu) | 3.04 | 3.00 | 3.10 | 3.06 | 2.98 | 2.98 | 2.99 | 3.05 |

| Ti | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Al | 2.00 | 2.31 | 2.23 | 2.42 | 1.98 | 2.21 | 2.36 | 2.42 |

| Cr | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Fe3+ | 0.94 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 1.00 | 0.73 | 0.60 | 0.48 |

| Mn3+ | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Mg | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Ca | 1.95 | 1.96 | 1.99 | 1.98 | 1.94 | 1.97 | 2.04 | 2.02 |

| Na | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| XPs (a) | 0.32 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.16 |

| Rock | Andesite | Granitoid | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Fp-FSC | VG-VGFR | |||||||

| Type | Chlorite | Chloritized-Biotite | Chlorite | Chloritized-Biotite | |||||

| Spot | #55 | #54 | #56 | #60 | #96 | #98 | #112 | #14 | #16 |

| SiO2 (wt%) | 26.29 | 27.63 | 28.63 | 29.96 | 29.29 | 28.30 | 26.94 | 27.80 | 29.49 |

| TiO2 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 2.07 | 0.11 |

| Al2O3 | 19.89 | 17.35 | 16.79 | 17.55 | 13.50 | 16.13 | 17.63 | 17.78 | 16.02 |

| FeOtot | 20.30 | 19.62 | 19.20 | 28.02 | 25.26 | 25.59 | 27.20 | 26.27 | 30.02 |

| MnO | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0.36 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.64 | 0.47 |

| MgO | 17.60 | 19.11 | 18.66 | 10.10 | 15.77 | 15.07 | 13.56 | 10.05 | 9.38 |

| CaO | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.58 |

| Na2O | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.11 |

| K2O | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.75 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 1.09 |

| Total | 84.85 | 84.53 | 83.94 | 87.94 | 84.00 | 85.48 | 85.66 | 85.31 | 87.26 |

| Formula (14 oxygens) | |||||||||

| Si, (apfu) | 2.79 | 2.92 | 2.99 | 3.10 | 3.13 | 2.97 | 2.85 | 2.95 | 3.11 |

| Ti | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.01 |

| Al | 2.48 | 2.16 | 2.07 | 2.14 | 1.70 | 2.00 | 2.20 | 2.22 | 1.99 |

| Al[iv] | 1.21 | 1.08 | 1.00 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 1.01 | 1.15 | 0.89 | 0.88 |

| Al[vi] | 1.27 | 1.08 | 1.06 | 1.25 | 0.83 | 0.99 | 1.05 | 1.33 | 1.10 |

| Fe2+ | 1.69 | 1.54 | 1.16 | 1.55 | 1.44 | 1.44 | 1.54 | 1.49 | 1.69 |

| Fe3+ | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.52 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.95 |

| Mn | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Mg | 2.78 | 3.01 | 2.91 | 1.56 | 2.51 | 2.36 | 2.14 | 1.59 | 1.47 |

| Ca | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Na | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| K | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.15 |

| XFe3+ (a) | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.36 |

| XMg (b) | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.72 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.58 | 0.52 | 0.47 |

| T (°C) (c) [±30 °C] | 329 | 286 | 262 | 225 | 218 | 264 | 309 | 225 | 223 |

| Rock | Andesite | Granite | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | FP-FPSC | VG-VGFR | |||||||||

| Type | Primary | Secondary | Primary | Secondary | |||||||

| Spot | #9 | #90 | #7 | #155 | #166 | #81 | #122 | #151 | #116 | #129 | #89 |

| SiO2 (wt%) | 46.61 | 42.34 | 47.35 | 52.81 | 51.99 | 50.86 | 51.59 | 50.28 | 52.96 | 49.50 | 51.93 |

| TiO2 | 0.98 | 3.47 | 1.30 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.02 |

| Al2O3 | 10.09 | 11.61 | 7.57 | 1.74 | 3.15 | 4.15 | 3.47 | 6.33 | 2.44 | 4.41 | 1.90 |

| FeOtot | 16.11 | 12.48 | 17.30 | 15.73 | 22.93 | 18.35 | 16.64 | 11.44 | 15.84 | 23.12 | 23.70 |

| MnO | 0.46 | 0.18 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 1.14 | 0.92 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.12 |

| MgO | 9.86 | 13.28 | 12.23 | 12.53 | 6.61 | 9.89 | 12.84 | 15.18 | 12.77 | 7.66 | 8.02 |

| CaO | 9.51 | 11.46 | 10.45 | 11.76 | 11.60 | 11.70 | 11.72 | 11.83 | 12.03 | 12.02 | 12.08 |

| Na2O | 1.47 | 2.13 | 1.22 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.57 | 0.78 | 0.45 | 0.89 | 0.25 |

| K2O | 2.21 | 0.79 | 0.57 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.16 | 0.41 | 0.27 |

| Total | 97.29 | 97.74 | 98.46 | 95.55 | 97.75 | 96.36 | 97.35 | 96.67 | 96.89 | 98.32 | 98.29 |

| Normalization Scheme: 13-CNK | |||||||||||

| Si, apfu | 6.90 | 6.18 | 6.81 | 7.87 | 7.86 | 7.63 | 7.55 | 7.24 | 7.80 | 7.49 | 7.83 |

| Al | 1.10 | 1.82 | 1.19 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 0.76 | 0.20 | 0.51 | 0.17 |

| ΣT | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 |

| Ti | 0.11 | 0.38 | 0.14 | 0.02 | - | - | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Al | 0.66 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.42 | 0.37 | 0.15 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.17 |

| Fe3+ | 0.36 | 0.54 | 1.14 | 0.09 | - | 0.12 | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.01 | - | - |

| Mn2+ | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Fe2+ | 1.63 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 1.87 | 2.90 | 2.18 | 1.65 | 0.93 | 1.94 | 2.93 | 2.99 |

| Mg | 2.18 | 2.89 | 2.62 | 2.78 | 1.49 | 2.21 | 2.80 | 3.26 | 2.80 | 1.73 | 1.80 |

| ΣC | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 4.95 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 4.97 | 4.98 |

| Ca | 1.51 | 1.79 | 1.61 | 1.88 | 1.88 | 1.88 | 1.84 | 1.83 | 1.90 | 1.95 | 1.95 |

| Na | 0.42 | 0.21 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| ΣB | 1.93 | 2.00 | 1.95 | 1.94 | 1.93 | 1.95 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Ca | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Na | - | 0.40 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.03 |

| K | 0.42 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| ΣA | 0.42 | 0.54 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.29 | 0.08 |

| O (non-W) | 22.00 | 22.00 | 22.00 | 22.00 | 22.00 | 22.00 | 22.00 | 22.00 | 22.00 | 22.00 | 22.00 |

| W (OH) | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Σ(T, C, B, A) | 15.35 | 15.54 | 15.06 | 14.95 | 14.91 | 15.00 | 15.07 | 15.12 | 15.06 | 15.26 | 15.06 |

| Species (a) | MgHbl | MgHbl | Tschk | Act | Fe-Act | Act | MgHbl | MgHbl | Act | Fe-Act | Fe-Act |

| Altot | 1.76 | 2.00 | 1.28 | 0.31 | 0.56 | 0.73 | 0.60 | 1.08 | 0.42 | 0.79 | 0.34 |

| P kbar (b) [±0.5 kbar] | 4.2 | 5.1 | 2.6 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.7 |

| T (°C) (c) [±30 °C] | 505 | 431 | 416 | 495 | 493 | 489 | |||||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lucci, F.; Della Ventura, G.; Conte, A.; Nazzari, M.; Scarlato, P. Naturally Occurring Asbestos (NOA) in Granitoid Rocks, A Case Study from Sardinia (Italy). Minerals 2018, 8, 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/min8100442

Lucci F, Della Ventura G, Conte A, Nazzari M, Scarlato P. Naturally Occurring Asbestos (NOA) in Granitoid Rocks, A Case Study from Sardinia (Italy). Minerals. 2018; 8(10):442. https://doi.org/10.3390/min8100442

Chicago/Turabian StyleLucci, Federico, Giancarlo Della Ventura, Alessandra Conte, Manuela Nazzari, and Piergiorgio Scarlato. 2018. "Naturally Occurring Asbestos (NOA) in Granitoid Rocks, A Case Study from Sardinia (Italy)" Minerals 8, no. 10: 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/min8100442

APA StyleLucci, F., Della Ventura, G., Conte, A., Nazzari, M., & Scarlato, P. (2018). Naturally Occurring Asbestos (NOA) in Granitoid Rocks, A Case Study from Sardinia (Italy). Minerals, 8(10), 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/min8100442