A Novel Process for the Synthesis of NaV2O5 Mesocrystals from Alkaline-Stripped Vanadium Solution via the Hydrothermal Hydrogen Reduction Method

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Synthesis Methods

2.3. Characterization

2.4. Electrochemical Testing

2.5. Data Treatment

3. Results and Discussion

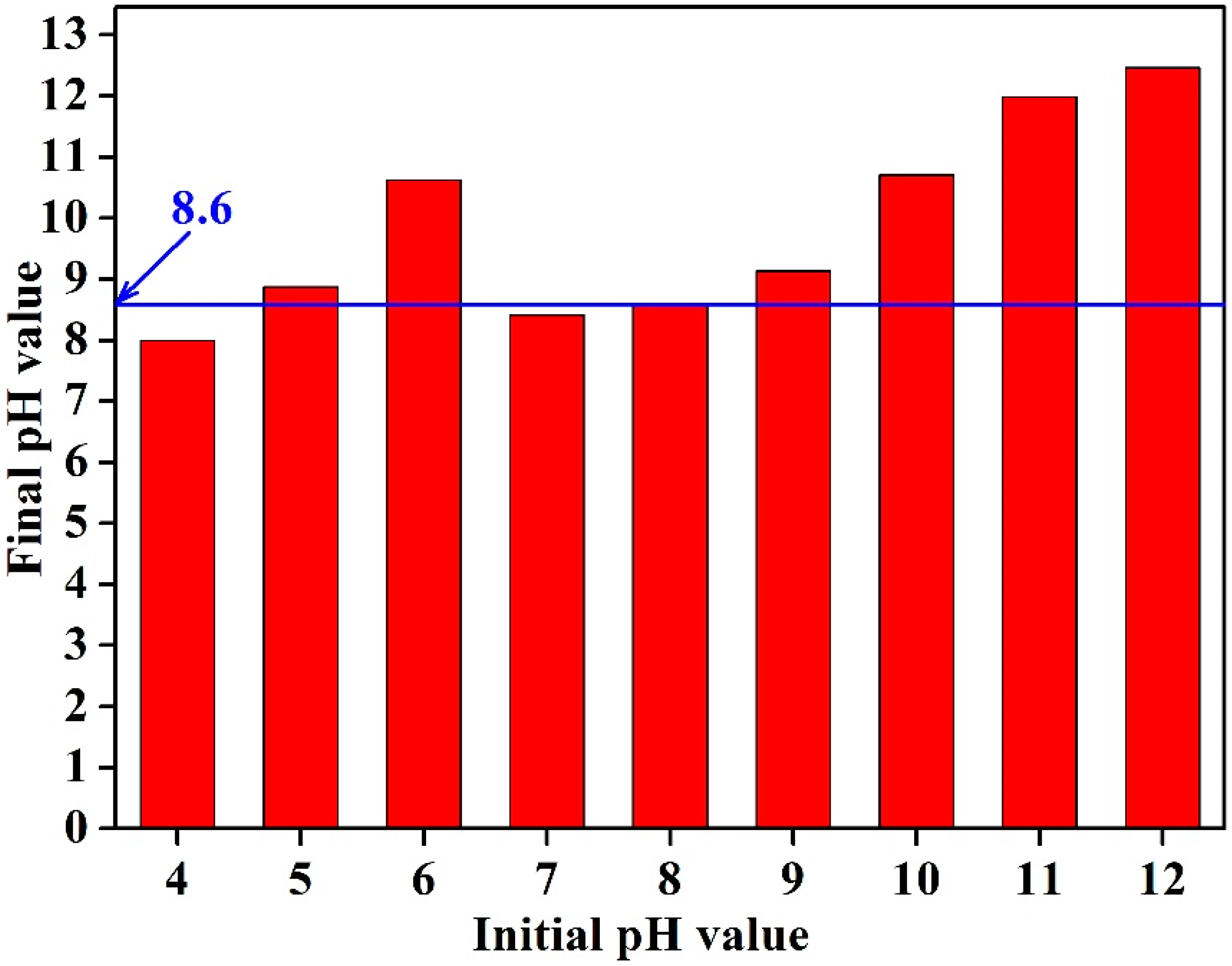

3.1. Effect of Initial Solution pH Value

3.2. Effect of Reaction Temperature

3.3. Effect of H2 Gas Partial Pressure

3.4. Effect of Reaction Time

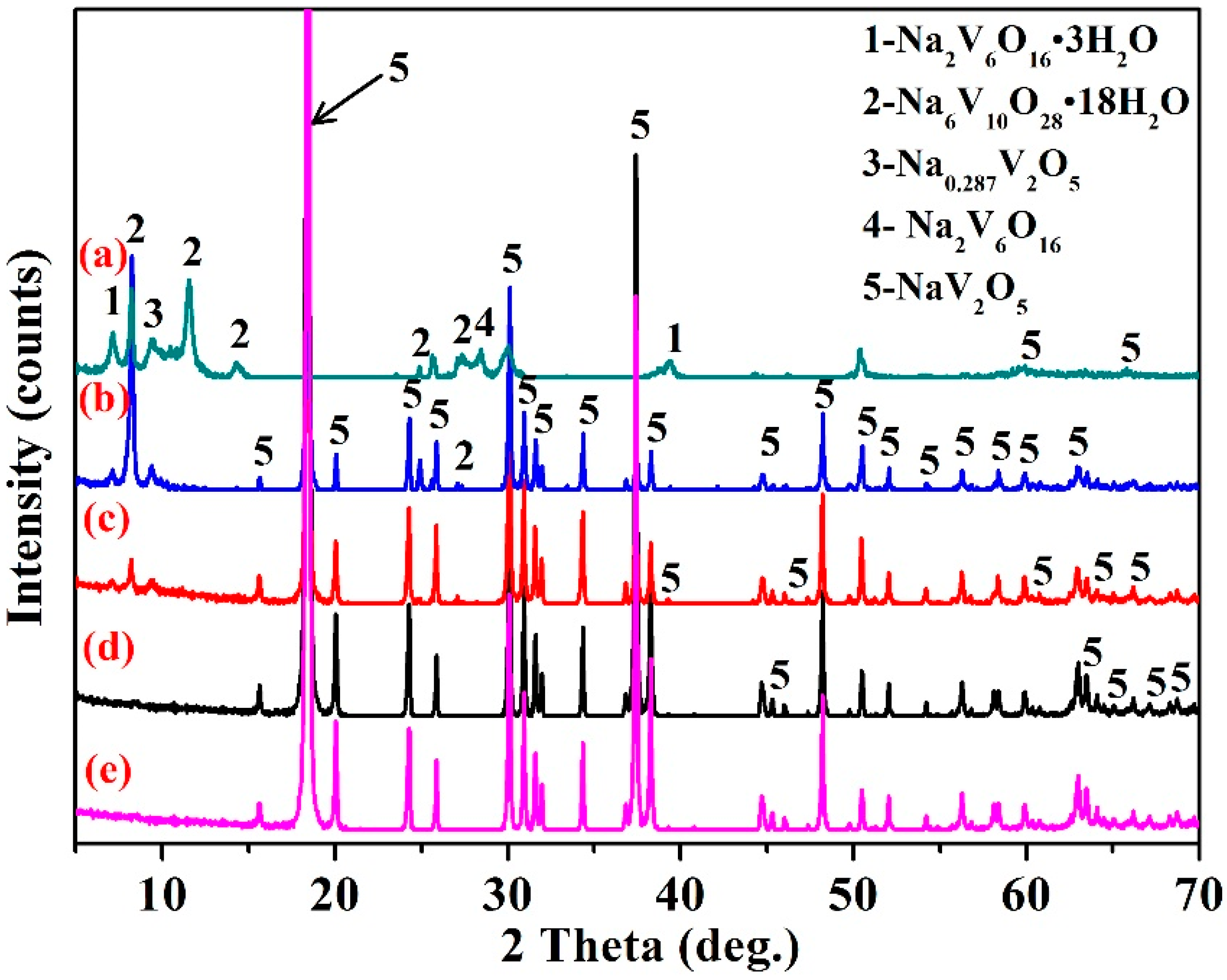

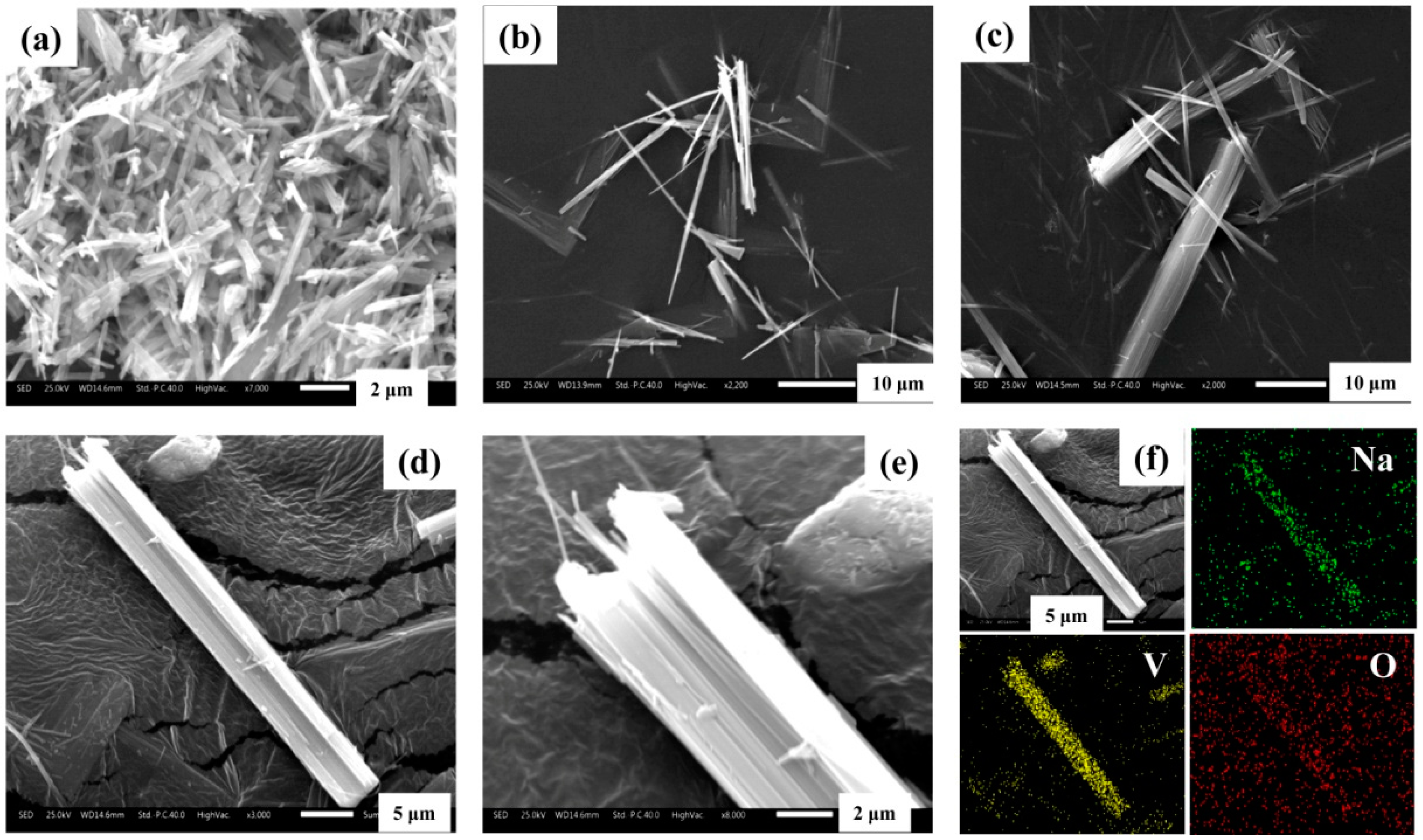

3.5. Structural Characterization

3.6. Electrochemical Performance

3.7. Synthesis Mechanism

3.7.1. Phase Transformation Mechanism

3.7.2. Crystal Growth Mechanism

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Huang, J.; Yuan, Y.; Xue, N. Source separation of vanadium over iron from roasted vanadium-bearing shale during acid leaching via ferric fluoride surface coating. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, J.; Liu, T.; Yuan, Y.; Xue, N. Eco-friendly leaching and separation of vanadium over iron impurity from vanadium-bearing shale using oxalic acid as a leachant. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 1900–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, N.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, J.; Liu, T.; Wang, L. Separation of impurities aluminum and iron during pressure acid leaching of vanadium from stone coal. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 1265–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, N.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Huang, J.; Zheng, Q. Effects of hydration and hardening of calcium sulfate on muscovite dissolution during pressure acid leaching of black shale. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mjejin, I.; Etteyeb, N.; Sediri, F. NaV2O5 nanoplates: Hydrothermal synthesis, characterization and study of their optical and electrochemical properties. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 5379–5386. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, F.; Ming, X.; Chen, G.; Wang, C.; Li, A.; Li, J.; Wei, Y. Synthesis and characterizations of highly crystallized α’-NaV2O5 needles prepared by a hydrothermal process. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 47, 888–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aichhorn, M.; Sherman, E.Y.; Evertz, H.G. Single-particle spectral function of quarter-filled ladder systems. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 72, 155110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamioka, H.; Saito, S.; Isobe, M.; Ueda, Y.; Suemoto, T. Coherent magnetic oscillation in the spin ladder system α’-NaV2O5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 127201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosihama, T.; Nishi, M.; Nakajima, K.; Kakurai, K.; Takesue, N.; Fujii, Y.; Isobe, M.; Kagami, C.; Ueda, Y. Magnetic excitations in spin-Peierls compound NaV2O5. Phys. B Condens. Matter 1997, 234–236, 539–540. [Google Scholar]

- Isobe, M.; Kagami, C.; Ueda, Y. Crystal growth of new spin-Peierls compound NaV2O5. J. Cryst. 1997, 181, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe, M.; Ueda, Y. Magnetic susceptibility of quasi-one-dimensional compound NaV2O5. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1996, 65, 1178–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsch, P.; Mack, F. A new view of the electronic structure of the spin-Peierls compound α’-NaV2O5. Eur. Phys. J. B 1998, 5, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohwada, K.; Fujii, Y.; Muraoka, J.; Nakao, H.; Murakami, Y.; Noda, Y.; Ohsumi, H.; Ikeda, N.; Shobu, T.; Isobe, M.; et al. Structural relations between two ground states of NaV2O5 under high pressure: A synchrotron x-ray diffraction study. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 094113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitaler, J.; Sherman, E.Y.; Draxl, C.A. Zone-center phonons in NaV2O5: A comprehensive ab initiostudy including Raman spectra and electron-phonon interaction. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 75, 014302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, X.; Fan, H.; Huang, Z.; Hu, F.; Wang, C.; Chen, G. Magnetic gap in Slater insulator α’-NaV2O5. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2008, 15, 155203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhu, K.; Bian, K.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, W.; Huang, W.; Zhang, J. One-step and short-time synthesis of 3D NaV2O5 mesocrystal as anode materials of Na-Ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2018, 395, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhu, K.; Gao, Y.; Luo, H.; Lu, L. Recent progress in the applications of vanadium-based oxides on energy storage: From low-dimensional nanomaterials synthesis to 3D micro/nano-structures and free-standing electrodes fabrication. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1700547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhou, D.; Zhu, K.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Tai, G.; Zhang, W.; Gu, Q. Bundle-like α’-NaV2O5 mesocrystals: From synthesis, growth mechanism to analysis of Na-ion intercalation/deintercalation abilities. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 1975–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller-Bouvet, D.; Baddour-Hadjean, R.; Tanabe, M.; Huynh, L.T.N.; Le, M.L.P.; Pereira-Ramos, J.P. Electrochemically formed α’-NaV2O5: A new sodium intercalation compound. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 176, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolinski, H.; Gros, C.; Weber, W.; Peuchert, U.; Roth, G.; Weiden, M.; Geibel, C. NaV2O5 as a quarter-filled ladder compound. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 80, 5164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, A.I.; Popova, M.N.; Sushkov, A.B.; Golubchik, S.A.; Khomskii, D.I.; Mostovoy, M.V.; Vasil’ev, A.N.; Isobe, M.; Ueda, Y. High-frequency dielectric and magnetic anomaly at the phase transition in NaV2O5. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 14546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, A.I.; Sosin, S.S.; Calemczuk, R.; Villar, V.; Paulsen, C.; Isobe, M.; Ueda, Y. Thermal and magnetic properties of defects in the spin-gap compound NaV2O5. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 63, 014412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoda, M.; Mizuguchi, Y. Correlation and disorder effects for the electronic transport in the correlation and disorder effects for the electronic transport in the low-dimensional system NaxCa1-xV2O5 and NaxV2O5. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2008, 20, 445207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Z.; Fan, R.; Chen, X.; Hu, Y.; Wu, Y. Hydrothermal synthesis and magnetic property of NaV2O5 nanorods. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2001, 11, 324–327. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Bao, S.; Liu, T.; Chen, T.; Huang, J. The technology of extracting vanadium from stone coal in China: History, current status and future prospects. Hydrometallurgy 2011, 109, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Bao, S.; Shen, C. Separation and recovery of vanadium from a sulfuric-acid leaching solution of stone coal by solvent extraction using trialkylamine. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016, 164, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Bao, S.; Huang, J.; Zhang, L. A novel eco-friendly vanadium precipitation method by hydrothermal hydrogen reduction technology. Minerals 2017, 7, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Bao, S. The effects of sodium ions, phosphorus, and silicon on the eco-friendly process of vanadium precipitation by hydrothermal hydrogen reduction. Minerals 2018, 8, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Kumar, V.; Pandey, B.D.; Sahu, K.K. A comprehensive review on the hydro metallurgical process for the production of nickel and copper powders by hydrogen reduction. Mater. Res. Bull. 2006, 41, 879–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, T.; Lindfors, L.E.; Fugleberg, S. A review of the precipitation of nickel from salt solutions by hydrogen reduction. Hydrometallurgy 1998, 47, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | V | Na | P | Al | Fe | Si | Mg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration (g/L) | 20.5 | 23.1 | 0.013 | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.012 | 0.008 |

| Items | V2O5 | Na | P | Al | Fe | Si | Mg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content (wt. %) | 88.74 | 11.24 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Bao, S.; Zhang, L. A Novel Process for the Synthesis of NaV2O5 Mesocrystals from Alkaline-Stripped Vanadium Solution via the Hydrothermal Hydrogen Reduction Method. Minerals 2019, 9, 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/min9050271

Zhang G, Zhang Y, Bao S, Zhang L. A Novel Process for the Synthesis of NaV2O5 Mesocrystals from Alkaline-Stripped Vanadium Solution via the Hydrothermal Hydrogen Reduction Method. Minerals. 2019; 9(5):271. https://doi.org/10.3390/min9050271

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Guobin, Yimin Zhang, Shenxu Bao, and Liuhong Zhang. 2019. "A Novel Process for the Synthesis of NaV2O5 Mesocrystals from Alkaline-Stripped Vanadium Solution via the Hydrothermal Hydrogen Reduction Method" Minerals 9, no. 5: 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/min9050271

APA StyleZhang, G., Zhang, Y., Bao, S., & Zhang, L. (2019). A Novel Process for the Synthesis of NaV2O5 Mesocrystals from Alkaline-Stripped Vanadium Solution via the Hydrothermal Hydrogen Reduction Method. Minerals, 9(5), 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/min9050271