Abstract

We introduce a Fuzzy Property Grammar System (FPGS), a formalism that integrates a Fuzzy Property Grammar into a linguistic grammar system to formally characterize metaphorical evaluative expressions. The main scope of this paper is to present the formalism of FPGS and to show how it might provide a formal characterization of hate speech linguistic evaluative expressions with metaphors (as fuzzy concepts), together with evaluating their degree of linguistic violence. Linguistic metaphors are full of semantic coercions. It is necessary to formally characterize the context of the communication to acknowledge the extralinguistic constraints of the pragmatic domain, which establishes whether an utterance is violent. To show the applicability of our formalism, we present a proof of concept. By compiling and tagging a 3000-tweet corpus, we have extracted a lexicon of hate speech metaphors. Furthermore, we show how FPGS architecture can deal with different types of hate speech and can identify implicit violent figurative evaluative expressions by context and type. Although we are still in the experimental phase of our project and cannot present conclusive results at the computational level, the proof-of-concept results show that our formalism can achieve the desired outcome.

MSC:

03B65

1. Introduction

In this paper, we consider the topic of hate speech from a linguistic point of view. Our main scope here is to provide a formalism that might help in the characterization and, therefore, the computational detection of hate speech.

The massive use of social networks has revealed a fact that, although it has always existed, was not so obvious: verbal violence. Understanding and detecting verbal violence in online discussions and social media are well-known challenges. In the last few years, there has been a lot of research on the automatic detection of verbal violence using different computational tools for automatically classifying and detecting online abuse (i.e., machine learning, natural language processing, and statistical modeling). Fortuna and Nunes [1], Fortuna et al. [2], Vidgen et al. [3], and Poletto et al. [4] offer interesting reviews of different challenges for the detection of abusive language.

By verbal violence, we understand an intended attack on another person’s positive (personality) or negative (freedom of action) face using language. In general, studies on linguistic violence distinguish many different categories: hate speech, offense, threat, insult, defamation, etc. In this paper, an insult is considered a strategy of hate speech, and we focus on expressions usually regarded as insulting. Although the term hate speech is employed for attacks on specific groups (based on differences such as race, sexual orientation or gender), it can be used broadly as a synonym for verbal violence.

The automatic detection of hate speech is related to the field of sentiment analysis. Sentiment analysis is an area that has received a lot of attention in recent years due to the massive use of social networks. Sentiment analysis consists of using computational tools to detect and analyze evaluative language in terms of polarity [5,6]. Polarity refers to the notion that sentiment conveyed by a particular word, phrase or text can be negative or positive, and its intensity can be reflected by a value on a scale, such as 0 to 10, or −5 to 5. The development of sentiment analysis tools, as well as the detection of hate speech, requires the formalization of evaluative language.

Modeling evaluative utterances and capturing or extracting the sentiment behind these linguistic expressions is certainly a challenge. Typically, machine learning and deep learning techniques are used for these tasks [7,8,9,10,11]. However, learning algorithms focus on aspects of computational performance and do not provide enough features from the point of view of explaining linguistic phenomena and processes. On the other hand, the linguistic analysis of those constructions is fundamental, since evaluative expressions are very subtle, with nonprototypical properties and variables in syntax, semantics, and sentiment (positive–negative).

In this paper, we assume that an insult is an evaluative expression [12,13,14,15]. Typical evaluative words are good, bad, high, low, big, small, stupid, silly, dumb, etc. These words are said to be vague, as it is very difficult to define their meaning. This vagueness makes it difficult to qualify or value a certain expression as more or less violent. It is, therefore, essential to characterize this vagueness to detect the evaluative expressions used in hate speech, whether these utterances use words typically considered evaluative or metaphors that are more difficult to detect.

We consider the metaphor as a linguistic evaluative expression in a formal model, and we introduce a formalism to generate and recognize metaphors, with the aim that this framework can lead to the implementation of a model to detect the sentiment in the evaluative expressions automatically. This model responds to the need to carry out a nuanced linguistic analysis to be able to detect the real sentiment when what is used is not a canonical evaluative expression but something habitual in language, such as metaphors, understood as the use of a word to refer to something different from its conventional meaning [16].

Since our main scope in this paper is to introduce the formalism of a Fuzzy Property Grammar System to generate and recognize metaphors, we do not show computational results here. However, we present an early stage demonstration that verifies that our formal framework is feasible from a technical and computational point of view. Our proof of concept focuses on a restricted type of metaphor, which has an “X is Y” structure.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides the formal prerequisites to understand the formalism introduced in this paper. Section 3 provides the formal and linguistic background for our proposal. Section 4 shows the characterization of insults as evaluative expressions in hate speech. Section 5 introduces a formal model for parsing metaphors. Section 6 presents a proof of concept of how to parse metaphors with Fuzzy Property Grammar Systems. Finally, Section 7 presents the discussion, conclusions, and future work.

2. Formal Prerequisites

Throughout this paper, we assume that the reader is familiar with the basics of Formal Language Theory. In this section, we give some of the formal prerequisites that are needed in order to understand the formalization presented in this work. For further information on the theory of formal languages, see Salomaa [17] and Rozenberg and Salomaa [18].

A set is a collection of elements taken from some prespecified universe. A set is finite if it contains a finite number of elements, and otherwise, it is infinite. A sequence of elements, from some universe, is a list of elements possibly, but not necessarily, with repetitions. Because the list is ordered by position, the elements are referred to as the 1st, 2nd, and i-th.

A finite, nonempty set V of symbols or letters is called an alphabet. A word or a string over an alphabet V is a finite sequence of symbols from V. The empty word is denoted by and is the empty sequence of symbols. For an alphabet we denote by the free monoid generated by V under the operation of concatenation, i.e., the set of all words over V. denotes the set of all nonempty strings over V. The length of a string (the number of symbol occurrences in x) is denoted by . The number of occurrences in of symbols is denoted by .

Given two words, x and y, over V, their catenation is . for all x in .

For two words x and y over V, x is a prefix of y if , for some z in . if x is a prefix of y and . x is a proper prefix of y if it is a prefix, , and . A suffix and proper suffix are defined similarly. x is said to be a subword of y if , for some w and z in . x is a proper subword if and

Given an alphabet V, a languageL over V is a subset of . Since languages are sets, the Boolean operations of union, intersection, and complement are applicable and defined in the usual way. Given two languages, and , possibly over different alphabets, the catenation of and is denoted and equals the set .

A grammar is a quadruple , where N is the nonterminal alphabet, T is the terminal alphabet, is the axiom (start symbol), and P is the set of rewriting rules (or productions), written as .

A direct derivation in G is denoted by ⟹ (by when we need this information). The transitive (reflexive) closure of the relation ⟹ is denoted by ().

The language generated by G, denoted by , is

3. Background

3.1. Formal Background

The formal model we introduce in this paper is based on grammar systems [19] and Fuzzy Property Grammars [20].

Grammar systems theory is a branch of the field of formal languages [19]. Roughly speaking, a grammar system is a set of grammars working together, according to a specified protocol, to generate a language. Note that while in classical formal language theory one grammar (or automaton) works individually to generate (or recognize) one language, here, we have several grammars working together in order to produce one language.

There are two basic types of grammar systems:

- Cooperating Distributed Grammar Systems (CDGS) that consist of a finite set of generative grammars that cooperate in the derivation of a common language. Component grammars generate the string in turns (thus, sequentially) under some cooperation protocol [21].

- Parallel Communicating Grammar Systems (PCGS) consists of several usual grammars which function in parallel [22].

Formally, a Cooperating Distributed Grammar Systems is defined as follows.

Definition 1.

A CDGS of degree n, is a construct:

where the following holds:

- N, T are disjoint alphabets;

- is the axiom;

- , , the so-called components of the system Γ, are usual Chomsky grammars without axiom, where the following holds:

- −

- N is the nonterminal alphabet;

- −

- T is the terminal alphabet;

- −

- is a finite set of rewriting rules over .

Definition 2.

Let Γ be a CDGS as defined above. Let . Then, we write , for , if there are words , such that the following holds:

- (i)

- ,

- (ii)

- , i.e., , , , .

Moreover, we write the following:

- iff , for some ;

- iff , for some ;

- iff , for some k;

- iff , and there is no with .

Definition 3.

Let Γ be a CDGS, and denote . The language generated by the system Γ in the derivation mode is

A Parallel Communicating Grammar Systems is formally defined as follows:

Definition 4.

A PCGS of degree n, is a construct:

where the following holds:

- are mutually disjoint alphabets;

- are called query symbols, and they are associated in a one-to-one manner to components ;

- ;

- , , the so-called components of the system, are usual Chomsky grammars, where the following holds:

- −

- N is the nonterminal alphabet;

- −

- is the set of query symbols;

- −

- T is the terminal alphabet;

- −

- is a finite set of rewriting rules over , for ;

- −

- is the axiom for .

Definition 5.

Given a PCGS as above, for two n-tuples , , , , we write if one of the next two cases holds:

- (i)

- , , and for each i, , we have in grammar , or and ;

- (ii)

- There is i, , such that ; then, for each such i, we write , , for , , ; if , , then [and , ]; when, for some j, , , then ; and for all i, for which is not specified above, we have .

Definition 6.

The language generated by a PCGS Γ as above is

Fuzzy Property Grammar (FPGr) is a formal linguistic theory which combines the formalism of Fuzzy Natural Logic from Novák [12,14,23,24,25,26,27,28,29] and linguistic constraints, heavily influenced by Blache’s Property Grammar constraints [30,31,32,33,34].

The model, and its mathematical architecture, are explained in Torrens-Urrutia et al. [20] and applied to the semantics of the theory of evaluative expressions of Fuzzy Natural logic in Torrens-Urrutia et al. [15], as well as on a computational experiment for computing degrees of linguistic universality and complexity [35].

Definition 7.

A Fuzzy Property Grammar () is a couple

where U is a universe

The subscripts denote types, and the sets in (2) are sets of the following constraints:

- is the set of constraints that can be determined in phonology.

- is the set of constraints that can be determined in morphology.

- is the set of constraints that characterize syntax.

- is the set of constraints that characterize semantic phenomena.

- is the set of constraints that occur on a lexical level.

- is the set of constraints that characterize pragmatics.

- is the set of constraints that can be determined in prosody.

The second component is a function

which can be obtained as a composition of functions , …, . Each of the latter functions characterizes the degree in which the corresponding element x belongs to each of the above linguistic domains (with regards to a specific grammar).

Technically speaking, in (3) is a fuzzy set, with the membership function computed as follows:

where .

Let us now consider a set of constraints from an external linguistic input . Each can be observed as an n-tuple . Then, the membership degree is a degree of grammaticality of the given utterance that can be said in arbitrary dialect (of the given grammar).

In FPGr, linguistic constructions in written language stands for a simplified version of an , because only three linguistic domains are relevant for this work, namely the syntactical domain (x), the semantic domain (s), and the pragmatic domain (), , whereas the others are neglected: .

Definition 8.

A construction is

Due to length constraints, we briefly introduce the main concepts and formalism of FPGr. These are the notions of linguistic category, linguistic constraint, and linguistic construction.

A linguistic category stands for a lexical category or part of speech. Every language’s grammar sets the part of speech that a language requires. For example, in the FPGr of the Spanish and English language, we distinguish the following parts of speech: (determiner), (adjective), (noun), (proper noun), (verb), (adverb), (conjunction), (subordinate conjunction), and (preposition).

A part-of-speech tagger is necessary to identify linguistic categories. Alternatively, a grammar could define the part of speech of a language by using linguistic constraints, for example, characterizing an in the English language as that category which prototypically modifies a .

FPGr is closely related to the framework of Universal Dependencies (UD) [36,37]. Therefore, we recommend using the UD parser to identify each part of speech.

A linguistic constraint stands for a relation that puts together two or more linguistic elements, such as linguistic categories or parts of speech. A linguistic constraint is also named property in FPGr.

Formally, a linguistic constraint is an n-tuple , where are linguistic categories. We usually have .

We mainly distinguish four types of constraints:

- General or universal constraints that are valid for a universal grammar (any language).

- Specific constraints that are applicable to a specific grammar.

- Prototypical constraints that definitely belong to a specific language, i.e., their degree of membership is 1. For example, we specify a prototypical object with subindex . Example: stands for prototypical constraint.

- Borderline or nonprototypical constraints that belong to a specific language with some degree only (we usually measure it by a number from [0,1]). We specify a borderline object with subindex . Example: stands for a borderline constraint.

The constraints that FPGr works with are the following (the A and B are understood as linguistic categories):

- −

- Linearity of precedence order between two elements: A precedes B—in symbols: . Therefore, a violation is triggered when B precedes A. Example: “The () student ()”, (). stands for satisfied constraint.

- −

- Co-occurrence between two elements: A requires B—in symbols: . A violation is triggered if A occurs but B does not. Example: “The () woman () plays rugby” (), but “woman () plays rugby” (). stands for violated constraint.

- −

- Exclusion between two elements: A and B never appear in co-occurrence in the specified construction—in symbols: . That is, only A or only B occurs. Example: “She () does maths”, (), but “He () boy () does maths” ().

- −

- Uniqueness means that neither a category nor a group of categories (constituents) can appear more than once in a given construction. For example, in a construction X, . A violation is triggered if one of these constituents is repeated in a construction. Example: “A () a () dog eats chicken” (in nominal construction: ).

- −

- Dependency. An element A has a dependency on an element B—in symbols: . Typical dependencies (but not exclusively) for are (subject), (modifier), (object), (specifier), (verb), and (conjunction). A violation is triggered if the specified dependency does not occur. Example: “Europe is a small () continent ()”, (), but “Europe is a small () fast ()”, ().

- −

- Obligation. This property determines which element is a head. It is expressed by the symbol □. This property is useful for semantics and pragmatics. It is used to trigger semantic and pragmatic constructions through lexical units. For example, an evaluative head is mandatory in the semantic construction of an evaluative expression. Example: Construction Evaluative Expression: .

Additionally, two key concepts for the formalization of Fuzzy Property Grammars are as follows:

- −

- Linguistic feature. Features specify when properties are going to be applied to a category. The typical feature to be represented is a linguistic function, such as the function of subject: . Features are always written as subindexes in a linguistic category, i.e., .

- −

- Conjunction or disjunction of categories on a constraint.

- −

- ∧: This symbol is understood as and. It allows grouping categories and features as a whole unit under a single constraint. Example: (a verb with a transitive feature requires a noun as subject and a noun as object).

- −

- ∨: This symbol is understood as or. It allows the grouping of different categories and features concerning the possible alternatives of a grammar regarding one constraint. Example: (a verb with an intransitive feature requires a noun as a subject or a proper noun as a subject or a pronoun as a subject).

For the formalization of semantics and pragmatics of Fuzzy Property Grammars two important notions are as follows:

- −

- Referent. A referent is a person or thing to which a linguistic expression refers to, typically the subject. It is expressed as a feature . Example: .

- −

- Linguistic pairing stands for the tasks or phenomena in which linguistic features associate two linguistic elements. On an evaluative expression, typically, the subject is paired with the object. A dependency relation between the head of the evaluation and the referent expresses this phenomenon. Example: .

- −

- Lexical unit, in FPGr, stands for the structures that work as a single part of speech; therefore, they only count as one entry on a lexicon.

- −

- Lexicon. In FPGr, the lexicon is the dictionary that holds the meanings of the words. FPGr considers two lexicons, one for the semantic meaning and another for the pragmatic meaning. FPGr, at this point, mainly deals with evaluative expressions’ meanings [15] (p. 10-11, 18).

- −

- Semantic meaning includes the prototypical meanings for each word. Example: the word beautiful in the sentence “The sunset is beautiful” is understood as a high value on the scale of the semantics of Beauty. Computation of the degrees follows the formalism of Novák [12,14,23,25,26].

- −

- The pragmatic meaning includes borderline meanings that have been acquired from the use of language and the understanding of the world’s knowledge. For example, the word pig in the sentence “John is a pig” is understood as an evaluation with a low value on the scale of the pragmatic meaning of Pleasing-Likability.

The notion of linguistic construction stands for a complex object built by combining a linguistic category and linguistic constraints. The constraints define the construction’s structure and meaning.

Table 1 is an example of a linguistic construction in a Fuzzy Property Grammar.

Table 1.

Spanish in subject construction.

Table 1 displays the constraints that define a NOUN as a subject construction in Spanish. We highlight the following elements:

- All the constraints below are prototypical syntactic constraints. For that reason, they are named, for example, .

- All Variability Properties are borderline constraints from . For that reason, they are named, for example, .

- All constraints below are borderline constraints from another construction with another category than a performing with a noun fit. For example, an adjective performing as a noun in Spanish: “El bueno es el tuyo” (“The good one is yours”), “bueno” (“good one”) is defined as .

3.2. Linguistic Background

The study of implicit meaning started with Grice. In studying meaning in logical operators, some conventionalist authors defended that logical connectors have two meanings: one in logic and another in natural language. In contrast, Grice demonstrated that logical operators could not have multiple meanings, but conversational factors induce different meanings. So, following the economy principle of the “Modified Ockham’s razor”, “senses are not to be multiplied beyond necessity” [38].

In his first study, Grice [38] started analyzing meaning itself and distinguishing between natural (meaningN) and non-natural meaning (meaningNN) by using two examples [38]:

- MeaningN: “Those spots meant measles”.

- MeaningNN: “Those three rings on the bell (of the bus) mean that the bus is full”.

This classification is based on factivity and volition: factivity is the univocal relation between a sign (X) and its meaning (Y) (if X is true, Y must be necessarily true), and volition is the control for the purposes, such as intention. Thus, natural meaning is factive and not under voluntary control; non-natural meaning is under voluntary control and is nonfactive.

The volition concept opens the door to intention. In Grice’s terms, “‘A meantNN something by x’ is roughly equivalent to ‘A intended the utterance of x to produce some effect on an audience by means of the recognition of that intention’”. So, this non-natural meaning has in itself a communicative intention, and implicatures are the epitome of meaningNN [39].

Grice exposed a double intention in communication: A primary intention to produce some effect on the audience and a secondary intention to produce this effect through the hearer’s recognition of the primary intention. Grice aims to avoid psychological explanations in his theory, following Frege’s basis [40] for a linguistic theory. Rationality is one of the basis of Grice’s logic in conversation, and it generates the Cooperative Principle and its maxims. Thus, communication is based on the recognizing of intentions. The human capacity of intention attribution allows the speech act uttered by the speaker to have an effect on the audience [16]. So, communication is not a mind-reading process but a rational and inferential process guided by the Cooperative Principle.

Grice defined sentences’ meanings as the linguistic or conventional meaning, what is literally said, and established the speaker’s meaning as the content the speaker intends to communicate [38]. The last is heavily dependent on the speaker’s intentions and their recognition by the hearer.

For this reason, Grice established different principles or rules that are taken for granted by the speaker and the hearer in communication [38]. Grice suggested that there is a principle that determines how language is used efficiently to achieve rational interaction in communication, called the Cooperative Principle [41]: “Make your conversational contribution such as is required, at the stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose and direction of the talk exchange in which you are engaged” [38].

On the assumption that such a general principle is acceptable, Grice divided it into nine maxims, under categories that result in accordance with the Cooperative Principle. In line with the four Kant categories, Grice calls these maxims Quantity, Quality, Relation, and Manner [38] and establishes a supermaxim for the Quality and Manner maxims:

- Quantity: make your contribution as informative as is required for the purposes of the exchange:

- −

- Do not make your contribution more informative than is required.

- Quality: try to make your contribution one that is true:

- −

- Do not say what you believe to be false.

- −

- Do not say that for which you lack adequate evidence.

- Relation:

- −

- Be relevant.

- Manner: be perspicuous:

- −

- Avoid obscurity of expression.

- −

- Avoid ambiguity.

- −

- Be brief (avoid unnecessary prolixity).

- −

- Be orderly.

Conversational maxims are followed by the speaker in emission and by the hearer in comprehension. For this reason, an utterance generates expectations that guide the hearer to infer the speaker’s meaning. The maxims allow the hearer to understand the speaker’s meaning, despite the fact that it might differ from the sentence’s meaning under the assumption that he or she is being cooperative.

The notion of implicature arises from the fact that in an utterance, the speaker can both say something and imply another content [39]. It is an inference itself because it is derived from an inferential process. Thus, an implicature is definable as a meaning or proposition expressed or implied by a speaker in the utterance of a sentence which is meant without being part of what is strictly said [41]. Grice [38] classified two types of implicatures by their properties:

- 1.

- A conventional implicature:

- Conventionality: triggered by a lexical item.

- Non-reinforcability: generates redundancy.

- Noncalculability: determined by conventional meaning.

- Nonuniversality: a tendency to project out of the context.

- 2.

- A conversational implicature:

- Defeasibility or cancellability: can disappear in certain linguistic or nonlinguistic contexts.

- Nondetachability: any linguistic expression with the same content tends to carry the same conversational implicature (exceptions are conversational implicatures that arise from the maxim of Manner).

- Calculability: can be derived via the Cooperative Principle.

- Nonconventionality: is noncoded in nature.

- Reinforceability: can be made explicit without producing redundancy.

- Universality: tends to be universal and motivated.

- Indeterminacy: may generate a range of indeterminate conversational implicatures.

Both conventional and conversational implicatures do not contribute to truth conditions, because they are not part of what is centrally said. Instead, what is said is related to the conventional meaning of linguistic expressions and is accessible after the processes of reference assignment, indexical fixation, and disambiguation [38]. In doing so, contextual information is needed, and for this reason, some authors criticized Grice’s definition: strictly what is said could be determined by what is implied and vice versa. This is called “Grice’s circle” or “the pragmatic intrusion”.

To solve this confusion, Grice reformulated his definition of what is said [42]:

- (1)

- By which U centrally meant that p;

- (2)

- Which is an occurrence of a type S part of the meaning of which is ‘p’.

Thus, what is said is a propositional notion, which is compositional and related to intention. This notion is based on possibility conditions instead of reality conditions. Grice based his definition on Stalnaker’s theory: truth can be defined by classical theories, related to a model representing reality, or by dynamical theories, related to participants’ acceptance of evaluation. In doing so, the proposition, what is said, is determined by context and the speaker’s attitudes to specific propositions. The truth evaluation is determined by circumstances (time and possible world). Therefore, the content depends on the conditions that make the attribution of content possible, which is not a psychological representation [43].

4. Characterizing the Evaluative Insult

In this section, we show the characteristics of the object that we want to model: the evaluative insult.

We are modeling the objects of the “insult” on social media as hate speech, especially the insults that are evaluative expressions. Therefore, we define an “insult” as an evaluation of the referent which will be understood as violent, offensive, or hating. Consequently, any feature of an evaluative expression will be found in an “insult”. Evaluative expressions display prototypical and nonprototypical evaluations. In the case of the “insult”, we distinguish the following:

- –

- “Plain” evaluative insult: typically, a prototypical evaluation with negative sentiment. In English, it is usually under the structure , and always with a copula as a nexus.

- –

- Evaluative insult with metaphor: typically, a nonprototypical or borderline evaluation with negative sentiment. In English, it is usually under the structure , and most of the time, with a copula as a nexus.

For this reason, we provide the characteristics of evaluative expressions and metaphors and their syntax, semantics, and pragmatics.

4.1. Insults as Evaluative Expressions

Evaluative expression are the expressions of natural language used by people to characterize features of objects or their parts [12,13,14,15], such as esteem, beauty, size, intelligence, proximity, and capability, among others. They have the general form

The Equation (6) presents the following characteristics:

- (1)

- is the core element which expresses the evaluation, and it can be grouped to form a fundamental evaluative trichotomy consisting of two antonyms and a middle term, for example, , , , etc. The triple of adjectives is taken as canonical. On the other hand, provides information about the general position on a scale for the specific property—the intensity of the ascribed property of a . Usually, it is represented by an intensifying adverb, such as “very”, “quite”, “absolutely”, etc.

- (2)

- Each fundamental evaluative trichotomy has a tag with a Linguistic Semantic Variable (LSV). For example, the LSV for is “Judgment”, the LSV for is “Intelligence”, the LSV for is “Capability-Skills”, etc. The tag set lexicon was built on a manual extraction and reclassification of the sentiment lexicon SO-CAL [7]. The LSV tag set English lexicon has 1419 lexical units, and the Spanish one has 1549. Both these tag sets are classified under 21 LSV tags. This task was performed by experts in Fuzzy Natural Logic and linguistics [15,20].

- (3)

- A is the formal semantic representation of any linguistic element which can be the head of an evaluation. Each grammar must establish which categories will be susceptible to a prototypical or nonprototypical evaluative head. For example, in English, adjectives very often are evaluative heads, while nouns are used as nonprototypical evaluative heads in metaphors. Therefore:

- −

- A “plain” evaluative insult is typically a prototypical : “John is stupid”. “Stupid” is an evaluation belonging to the fundamental evaluative trichotomy of .

- −

- An evaluative insult with metaphor is typically nonprototypical and marked by connotative meaning: “John is a donkey”. ”Donkey” is a nonprototypical version of the evaluation “stupid”. If we were assuming the denotative meaning, we were saying that we literally are talking about a “donkey” (animal) named “John”. We represent such connotative meaning by representing it with the fundamental evaluative trichotomy of .

- (4)

- Possible world. It is a specific context in which a is used. In the case of evaluative expressions, it is characterized by a triple . Without loss of generality, it can be defined by three real numbers , where . These numbers represent an interval of reals , where is marked to emphasize the position of “typically medium”, is marked to emphasize the position of “typically small”, and is marked to emphasize the position of “typically big”. For more detailed information, see Novák [23]. Linguistic Semantic Variable

- (5)

- Intension. The intension of a refers to its linguistic semantic meaning. For prototypical evaluative expressions, the intension is independent of a concrete possible world (context) and does not change when the context is changed. For example, the word “stupid” will prototypically have the tag of being an object with a Linguistic Semantic Variable (LSV) of “Intelligence”, belonging to . In contrast, the word “intelligent” will prototypically be part of .

- (6)

- Sentiment and evaluation. The lexicon of evaluative expressions [15] is designed to relate with evaluations of positive sentiment and with an evaluation of negative sentiment. Therefore, any prototypical and nonprototypical evaluative insult with an evaluative tag belonging to will automatically have a negative sentiment.

- (7)

- Extension. In this work, the extension represents the intensity of the evaluation, similar to a Likert scale from [0–11]. That is because a real number cannot represent the extension of an evaluation most of the time. For example, in “This room is cold”, “cold” could easily have a real number expressed in degrees of temperature. However, in "John is a rat", and "I hate rats”, we have two , “rat” and “hate”, which cannot be defined by any real number that is not just expressing a scale of intensity.

4.2. Metaphors as an Insult

Since Aristotle, a metaphor has been defined as the use of some word to define another one different from its conventional meaning [16]. It is, in fact, the use of a sign in terms of another one, a conceptual relation between two terms.

Metaphors have implications by which some characteristics from our experience are highlighted. They can define our reality through an implications’ network that enhances some aspects of our experience [44]. Metaphors are usually employed to understand some identifiable concept. They are a type of representational transformation from a concrete domain to an abstract domain [45].

One or more semantic features were defined as the metaphorical class (y) and the literal class (x) by a set of semantic features by Khatin-Zadeh and Vahdat [46]. The metaphorical class contains a set of entities that share one or more semantic feature. Every entity can be used in a different position, such as topic, x, as the subject of the metaphor, or vehicle, y, as the term used metaphorically. Then, every semantic feature is related to a semantic feature of the conceptual meaning.

Therefore, using a metaphorical construction is a type of categorization. Lakoff and Johnson [44] explained that categorizing is a natural way of identifying a type of object, enhancing some properties and hiding other ones. The challenge is explaining how we select every feature in connecting the two objects (x, y).

From the point of view of semantics, metaphors can be comprehended without context and speaker’s intentions. Two theories can be highlighted: the theory of feature interaction and the theory of the elided comparison. The first affirms that the meaning of a word is decomposed in semantic features, so the use of a metaphor depends on the lexical features’ combination of the units employed. The second defends that every metaphor is an underlying comparison and can be rebuilt.

In philosophy studies, truth has been considered an objective and absolute truth. As has been explained, we use the term “truth” in terms of possibility conditions in specific circumstances and as the acceptance of them by the participants in that situation. Then, the speaker’s intentions and his/her conceptual system must be considered in evaluating the truth in his/her utterances.

Lakoff and Johnson [44] affirms that the truth in assertions depends on the categories employed and their appropriateness. Therefore, the truth is relative to how categories are comprehended and by our aims in a specific context [44].

In Grice’s theory, metaphor is considered an open violation of a quality’s maxim based on truth. Thus, Grice explained that metaphors “involve categorical falsity, so the contradictory of what the speaker has made as if to say will, strictly speaking, be a truism” [38]. In this falsity, the speaker is “attributing to his audience some feature or features in respect of which the audience resembles (more or less fancifully) the mentioned substance” [38]. Considering the Cooperative Principle that guides communication, the hearer must go into figurative meaning, that is, nonliteral meaning, in searching for the truth of the speaker’s intention.

Metaphors typically have the structure of “X is Y”. Not all languages might use a copulative verb “to be” as a nexus between “X” and “Y”; however, an element of nexus between the two is likely to be necessary in most languages.

However, our work focuses on modeling metaphors as evaluations. Therefore, we argue that the meaning of the metaphor is an evaluation that can be extracted from pairing the features of “X”, the referent, and “Y”, the nonprototypical evaluative head, taking into consideration the context as the element that triggers linguistic constraints in the pragmatic domain. In other words, the context found in the discourse (the topic of conversation) or the extralinguistic information as the communicative context will trigger linguistic constraints in the pragmatic domain representing the pragmatic information, such as metaphors.

Regarding how to process metaphors as evaluations, a formal description only considering the semantic field will encounter problems, failing in the pairing between the referent and the evaluative head.

In contrast, pragmatics will find such pairing as grammatical and satisfactory, since the pragmatic grammar will find coincidences in the pairing of referent and evaluation, since pragmatics consider meaning that includes interpretable and nonliteral information. This is because the linguistic constraints of the semantic and pragmatic grammar in our grammar systems are different. After all, they define two distinct linguistic domains. Consequently, two grammars can diverge on their degree of grammaticality as an output for the same utterance.

5. Fuzzy Property Grammar Systems

To model metaphors, our formal model integrates a Fuzzy Property Grammar from Torrens et al. [15,20,35] on a linguistic grammar system from Jiménez-López [47]. The Fuzzy Property Grammars characterize linguistic phenomena, giving information regarding language understanding. Furthermore, the linguistic grammar system establishes how each Fuzzy Property Grammar will work in parallel in a system of grammars that provides a total description of a language structure (syntax, semantics, pragmatics, language sentiment, etc.). By combining the two models, we would provide an explicative, white-box model which describes the processing of “plain” evaluative insults and evaluative insults with metaphor.

In what follows, we provide the formal definition of Fuzzy Property Grammar Systems.

Definition 9.

An FPGS of degree , with , is an -tuple:

where the following holds:

- are the components of the system:

- −

- , is the "master" of the system, where the following holds:

- *

- is the nonterminal alphabet;

- *

- is the terminal alphabet;

- *

- There is no axiom;

- *

- , for , is a Fuzzy Property Grammar where the following holds:

- ·

- is the nonterminal alphabet;

- ·

- is the terminal alphabet;

- ·

- U is a universe;

- ·

- ;

- ·

- is a finite set of constraints called properties.

- *

- is the derivation mode of

- −

- , for , is a CDGS where the following holds:

- *

- is the nonterminal alphabet;

- *

- is the terminal alphabet;

- *

- is the axiom;

- *

- , for , is a Fuzzy Property Grammar where the following holds:

- ·

- is the nonterminal alphabet;

- ·

- is the terminal alphabet;

- ·

- U is a universe;

- ·

- ;

- ·

- is a finite set of constraints called properties.

- *

- is the derivation mode of

- −

- , is the input filter of the master.

- −

- , , is the output filter of the i-th component.

- We write and .

- The sets , are mutually disjoint for any i, .

- We do not require , for , .

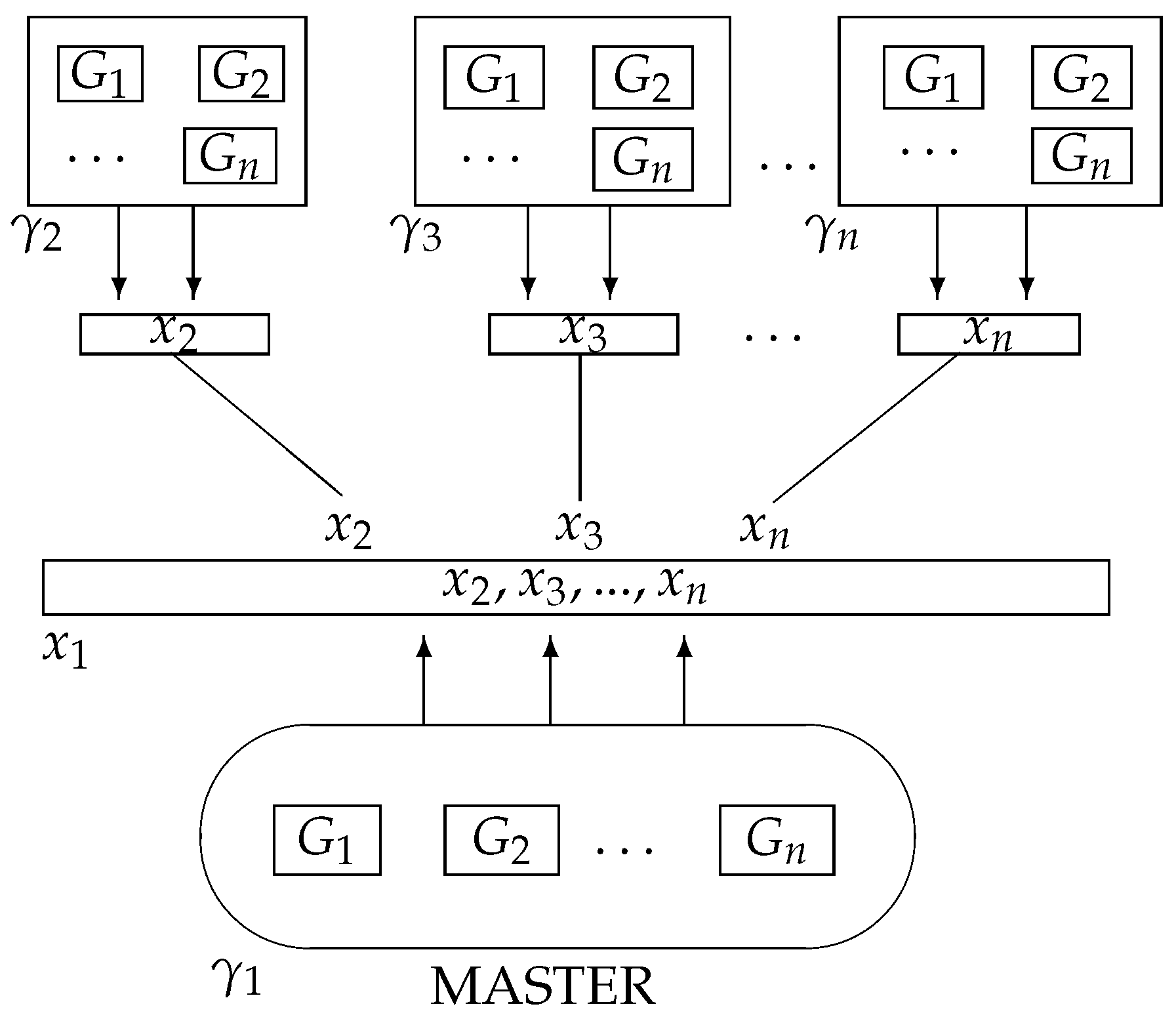

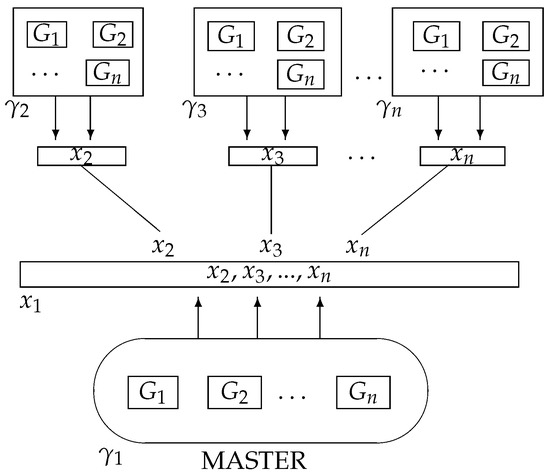

By defining a Fuzzy Property Grammar System (FPGS) as a PCGS, we have the possibility to have different modules that represent independent levels of linguistic representation (syntax, semantics, pragmatics etc.) that work in parallel with independent sets of constraints and basic vocabulary. Moreover, by considering that every component of the PCGS is a CDGS, we can consider a second level of modularity, since every component in the PCGS is divided into several different modules that work sequentially, cooperating with each other in order to account for the structure of the corresponding module (syntactic, semantic, pragmatic, etc.). FPGS could thus be considered as a doubly modular framework: it is modular firstly in that it is made up of several modules that work in parallel, and secondly, because every module in the system is internally modular. Moreover, a special transmodular module, the master, is considered in order to generate the language of the whole system.

Definition 10.

Given an FPGS , its state is described at any moment by an n-tuple , where each , , represents the string that is available at node i at that moment.

We specify the state of an FPGS as any moment in time in a tuple in which every module has a specified string.

Definition 11.

Given an FPGS , for two n-tuples , , , , we write if one of the following cases holds:

- 1.

- , and for all i, , we have in the CDGS , or and .*For each , for , with we write , for , if there exists , such that the following holds:

- ,

- , i.e., , , , .

- 2.

- iff for

The above definition captures the two different types of steps in the derivation process:

- In 1, we represent a rewriting step that accounts for the generation of the representation associated with each component of the system; this is the syntactic string, the semantic string, the pragmatic string, etc. Therefore, every grammar in the system rewrites its string according to its specific rules.

- In 2, we represent a communication step that accounts for the interaction among modules.

The derivation process functions by rewriting steps in every component. The process finishes when, after reaching a terminal string, every grammar in the FPGS sends its result to the master. As soon as the master has all the strings generated by the different modules of the system, its generates the language of the system.

Definition 12.

The language generated by an FPGS as above is

The above definition shows that we obtain a single language. The language of the system is the result of combining, via master, every structure generated by every component in the FPGS.

Figure 1 represents an FPGS.

Figure 1.

A Fuzzy Property Grammar System.

6. A Formal Model for Parsing Metaphors: A Proof of Concept

In this section, we show with an example how a Fuzzy Property Grammar System (FPGS) can describe two different types of insults: (1) a plain insult as an evaluative expression and (2) an insult with metaphor as an evaluative expression. These examples are extensible to any other insult that has been extracted during the creation of our corpora (Section 6.1).

6.1. Materials and Methods

To make our proposal applicable to natural languages, we built a linguistic lexicon of insults with and without metaphors for the Spanish language using a corpus-based methodology.

To build the lexicon, we extracted 3000 tweets on different topics in Spanish. We had to work with small data since only linguists, as experts, can tag the corpus and consider the necessary conditions for the utterances to build the lexicon.

We considered the following conditions during the tweet analysis to include an utterance in our lexicon:

- (1)

- First, the selection of 3000 tweets is applied only to the topics of social and political news and TV programs. The reason for choosing these topics is that people produce utterances with a lot of verbal violence when discussing these topics online. Therefore, much hate speech with and without metaphors will be found in these.

- (2)

- Secondly, we select the tweets that have been potentially understood as insults; therefore, they contain verbal violence.

- (3)

- Thirdly, we select the tweets that can be understood as evaluative expressions.

- (4)

- Fourthly, we separate “plain” insults from insults with metaphors, considering metaphors those which have one of the core forms of a metaphor in Spanish:

- −

- X es un/a Y. (“X is a Y”).

- *

- Example: “Juan es una rata” (“Juan is a rat”).

- −

- el/la Y. (“Determiner-male gender/Determiner-female gender X”).

- *

- Example: “El rata” (“the-male rat”).

- −

- X, el/la Y. (“X, Determiner-male gender/Determiner-female Y”)

- *

- Example: “Juan, el rata” (“Juan, the-male rat”)

- −

- Y (using the metaphor straightaway, referring to a person by a tweeter mention)

- *

- Example: “RATA @Juan” (“RAT @Juan”).

Additionally, for every tweet, several items of information are included: time, user, username, message, hashtag, likes, retweets, and replies. With this information, a situational view is obtained. Including situational information that Twitter offers avoids considering slurs or insults in isolation. The aim is comprehending verbal violence tweets in context, not as particular words that contain violence per se.

We focus not only on words with a conventionalized pejorative meaning but also on words with a common meaning that can be used to insult someone through the use of metaphor. Specific topics, time, retweets, and replies can promote verbal violence: the former is needed for fixing the references, and the latter generates a sharing circle due to the number of readings.

Considering all the above, we manually tagged the corpus. The potentially insulting expressions’ annotation step was carried out by three linguists as experts, while one expert, the referee, conducted the tweet analysis and the final linguistic annotation in case of disagreement.

The corpus is annotated in four phases.

6.2. First Phase of the Corpus Annotation Task

The first phase includes the following considerations:

- (1)

- Three linguists as experts tag every tweet as violent or nonviolent. A definition of verbal violence is provided to the experts to achieve a high agreement level: “language act that threatens the hearer’s or referred person’s face (self-concept), it is based on social norms and is perceived as an intentional act”.

- (2)

- Only violent tweets are tagged as explicit or implicit. To know which ones are implicit or explicit, we use the notion of cancellability. A cancellable meaning stands for a meaning that can disappear in certain linguistic or nonlinguistic contexts, or because of the addition of another statement.

- −

- Implicit tweets are those that can be cancellable and reinforced without redundancy.

- *

- Example: “Es una garrapata“ (”She is a tick”) can be canceled by adding “pero no digo que sea desagradable“ (“but I’m not saying she is unpleasing”) and reinforced by adding “y es desagradable y mala persona” (“and she is unpleasing and a bad person”).

- −

- We consider every tweet explicit when verbal violence cannot be cancellable or reinforced.

- *

- Example: “los subnormales” (“the retarded ones”) cannot be canceled by adding “pero inteligentes” (“but intelligent”) or reinforced by adding “y con poca inteligencia” (“and with little intelligence”).

- (3)

- Implicit tweets are analyzed in terms of maxims violated by the Gricean approach. Because it conveys rhetorical messages, we focused on the Quality maxim, assuming truth pairing between prototypical formal semantic features.

- −

- Example: “@isabel Pollo” (“@isabel Chicken”) cannot be true or demonstrable from the point of view of formal semantics, because a person cannot be an animal.

- (4)

- The evaluators had to tag each tweet as violent or nonviolent, always considering the above-mentioned conditions.

Table 2 shows the results of our violent or nonviolent annotation task.

Table 2.

Results of violent and nonviolent annotation task.

Table 2 shows that from the 3000 tweets analyzed, 47% are nonviolent and 53% are violent. In the next step, the 53% of tweets that are violent are annotated as explicit or implicit.

6.3. Second and Third Phase of the Corpus Annotation Task

The second and third annotation step was carried out by one expert, the referee. First, every tweet was annotated as explicit or implicit, taking into account the possibility of cancellation and reinforcement [38].

Table 3 contains the results of this second annotating task.

Table 3.

Results of explicit and implicit annotation task.

Table 3 displays that 53% of the total tweets are violent. Of these, 27.84% are implicit and 72.15% are explicit. Although this difference can be seen as not equivalent, it is relevant, considering that it communicates verbal violence. Implicit messages can be canceled, so that verbal violence can be outside of the speaker’s responsibility.

Finally, the third annotation step was also carried out by one expert, the referee. Every tweet is annotated as containing a metaphor or an insult. Every word that is conventionalized because it can not be canceled and does not allow reinforcement is considered an insult. In contrast, every word that can be canceled and whose implicature can be reinforced is considered a metaphor. The examples that do not contain a metaphor or an insult but are violent can include accusation, rejection, belittling, or threat, and for this reason, they are not considered in this annotation phase. Table 4 shows the results of this third annotation task.

Table 4.

Results of metaphor and insult annotation task.

Table 4 shows that insults are present in 68.84% of the implicit messages, and metaphors are in 7.22% of the tweets of implicit messages.

6.4. Fourth Phase of the Corpus Annotation Task

Both metaphors and insults are tagged with an evaluative tag from the theory of evaluative expressions modeled with Fuzzy Natural Logic from Novák [23,24,25,26]. In addition, we used the tags from the theory of evaluative expressions from Torrens et al. [15] to make explicit the meaning of both evaluative insults and evaluative insults with metaphors.

The tags for evaluative expressions are displayed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Linguistic Semantic Variable (LSV) and Prime Evaluative Head (EH) tags in Fuzzy Natural Logic (FNL) Lexicon from Torrens et al. [15] (p. 18).

Table 6 displays the distribution of these tags along the corpus.

Table 6.

Results of semantic evaluative tagging in metaphor and insult annotation task.

Table 6 contains the results of associating evaluative tags with metaphors and plain insults. From the total 337 insults and metaphors, we found that 261 (77.44%) were repeated. Therefore, repeated insults and metaphors were removed, leaving a total of 76 tags: 36 evaluative tags for insults and 40 evaluative tags for metaphors.

Table 7 shows the results of our tagged lexicon from Table 6 in detail. We distinguish the following:

Table 7.

Linguistic Semantic Variable (LSV) tags of evaluative expressions in the metaphor and insult annotation task.

- Two groups of lexical items used as a metaphor:

- (1)

- Lexical items from Spanish with semantics of an animal () used as a metaphor as an evaluative expression.

- (2)

- Lexical items from Spanish with semantics of a cultural character () used as a metaphor as an evaluative expression.

- One group of lexical items used as plain insults for humans ().

Each lexical item appears on the left side of the table, in the first column, and it is translated into English. On its right, it has a Linguistic Semantic Variable tag regarding how it was used as an evaluative expression in the corpus. All the lexical items are identified as , which means they are on the left fuzzy set of the fundamental evaluative trichotomy, tagged by a linguistic variable between angles .

On the one hand, plain insults display a specific evaluation meaning with negative sentiment (only one tag). For this reason, lexical items that at first might seem metaphorical, such as clown, are considered lexicalized. Consequently, 34 insults compile 36 tags. On the other hand, metaphors display more complex evaluative tags, with more than one evaluative tag per metaphor. For this reason, 18 metaphors present 40 evaluative tags. Each of the tags of the metaphor will arise in a specific context.

Insults are related to intelligence, judgment, and esteem: evaluative expressions with negative sentiment. Metaphors are broader. They can be connected to the prime evaluative tags intelligence, capability-skills, beauty, pleasing, fear-courage, judgment, and esteem.

6.5. Parsing Plain Insults and Insults with Metaphor

Consider the following two different types of insults:

- (1)

- A plain insult as an evaluative expression: “El presidente es estúpido” (“The prime minister is stupid”).

- (2)

- An insult with metaphor as an evaluative expression: “(El presidente es un burro)” (“The prime minister is a donkey”).

Through these two examples, we show how a Fuzzy Property Grammar is capable of providing a grammar for each linguistic domain, so they can work separately and provide different outcomes.

Let us consider that our FPGS consists of the following components, each containing different terminal and nonterminal alphabets, as well as different constraints:

- Syntactical CDGS: with terminal and nonterminal vocabulary and syntactic constraints.

- Semantic CDGS: with terminal and nonterminal vocabulary and syntactic constraints.

- Pragmatic CDGS: with terminal and nonterminal vocabulary and syntactic constraints.

- Master (the lexicon): words and rules for coordinating the structures generated by the three modules.

FPGS starts functioning as soon as every module starts its derivation process:

- Within the syntactic module, several grammars, each responsible for a different type of construction (e.g., ), cooperate distributively, and sequentially, in order to produce a well-formed syntactic structure.

- Within the semantic module, several grammars, one for each type of construction, cooperate sequentially in order to produce a semantically well-formed structure.

- Within the pragmatic module, where each component is responsible for a type of construction, the generation of a well-formed pragmatics structure takes place sequentially.

- In the meantime, while those three modules are working independently, nothing happens in the master, since this module does not contain any information; it must wait for strings produced by the other three modules.

If we consider our examples, we can compare what happens in our FPGS. For the plain insult, the syntactic component applies the constraints to the sentence and produces a satisfactory outcome, as shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

FPGr of Syntax as a plain insult.

A satisfactory outcome is also shown by Table 9 for the insult with metaphor.

Table 9.

FPGr of Syntax as an insult with metaphor.

However, Table 10 is a variation with particularities that already raise remarkable information regarding the possibility of the sentence “El presidente es un burro” being an evaluative construction. In Spanish, evaluative sentences are typically triggered by the pairing of a and , not by a pairing of and . Additionally, a prototypical constraint of Spanish is that an cannot specify a . However, it is entirely possible to do so in the sentence “El presidente es muy burro” (“the president is very donkey”), meaning “he is very stupid”. FPGr solves this situation by triggering borderline or nonprototypical constraints that describe such construction as a fitting an construction. Therefore, FPGr marks it by specifying that the is performing as an , evaluating the grammaticality of the syntax grammar as Barely satisfied, and not Satisfied or Unsatisfied. Compare Torrens-Urrutia et al. [20] (pp. 20–23) for how FPGr computes grammaticality.

Table 10.

FPGr of Syntax as an insult with metaphor with a borderline adjective .

From the point of view of semantics, our semantic CDGS provides different outcomes in the two examples considered.

There is a constraint rule in the semantic grammar of Spanish which triggers an evaluative expression construction:

Therefore, in Spanish, it is necessary to pair a as a referent () and an as an evaluative head () to trigger an evaluative expression for the semantic grammar in our grammar system. This is characterized in Table 11.

Table 11.

FPGr of Semantics as a plain insult.

Table 11 displays the satisfaction of , together with satisfied pairing of the words“Presidente” (“Prime Minister”) and “estúpido” (“stupid”). The semantic grammar finds the word “estúpido” (“stupid”) in its lexicon as an evaluative expression. The semantic lexicon provides the evaluative tag of the Linguistic Semantic Variable of Intelligence. This tag is accepted by "Presidente” (“Prime Minister”), since this feature is inherent to the feature of being “”. The Linguistic Semantic Variable of Intelligence coincides with the prototypical evaluation that provides the word “estúpido” (“stupid”). The meaning of the word “estúpido” (“stupid”) is understood as from the fundamental trichotomy of . Additionally, the lexicon also provides the sentiment for the evaluation, defining it as a negative sentiment by having it tagged as .

On the other hand, Table 12 displays how the semantic grammar fails to satisfy the pairing for two reasons. Firstly, because the lexicon does not have any information of the word “burro” (“donkey”) as an evaluative head, and consequently, the rule is violated. Secondly, the semantic grammar finds two semantic features in exclusion: an animal feature and a human feature . Therefore, Table 12 is an example of unsatisfied pairing and semantic implausibility. Consequently, the only possible interpretation for the sentence “El presidente es un burro” (“The president is a donkey”) is that the semantic grammar would understand it as a description, where the president of a country is actually the animal donkey, which is highly implausible; this is because a semantic grammar mostly characterizes the literal meaning.

Table 12.

FPGr of Semantics as an insult with metaphor.

Finally, regarding the pragmatic component, we can see that there is a constraint rule in the pragmatic grammar of Spanish which triggers an evaluative expression construction:

Therefore, with Equation (8), we formalize that a metaphor is essentially a pairing between a and a , and it is the pragmatic grammar that gathers information about how to establish a relation of meaning between the two.

Table 13 displays the satisfaction of the constraint rule of through the pairing of the words “Presidente” (“Prime Minister”) as the referent and “burro” (“donkey”) as the evaluative head. This outcome is possible since the pragmatic grammar finds the word “burro” (“donkey”) as an evaluative head in its lexicon. This evaluative head has been acquired through language usage. Because it is considered an evaluation for pragmatic grammar, it displays all the same features as any other standard prototypical evaluation, as in Table 11.

Table 13.

FPGr of Pragmatics as an insult with metaphor.

For both examples, derivation processes in our FPGS take place in parallel and independently. Derivation processes in each of these three modules continue until they reach three terminal strings. Each module will send its own terminal string to the master. So, the master will get a syntactic, a semantic, and a pragmatic string, respectively.

Once the master has received strings produced by every module of the system, it starts its work. The master’s task consists of lexicalizing the structures it has received; that is, its task is to rewrite the syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic structures by introducing words (a rewriting rule expresses an instruction to replace A by X. In this case, N symbols will be replaced by T symbols). If it is possible to lexicalize these structures, that is, if they are compatible and they can be lexicalized by means of the same words, then we can say that the master has successfully reached a terminal string and that, therefore, a well-formed natural language expression has been generated by the FPGS. In our case, the plain insult as an evaluative expression, “El presidente es estúpido” (“The prime minister is stupid”), will be considered a totally well-formed natural language expression, since it fits syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic constraints and it can, therefore, be lexicalized with the same lexical items. However, the example with an insult with metaphor as an evaluative expression: “(El presidente es un burro)” (“The prime minister is a donkey”) will be good from a syntactic and pragmatic point of view but an ill-formed structure from the point of view of semantics.

Therefore, the Fuzzy Property Grammar System model successfully displays different outcomes and properties by providing different grammars per linguistic domain for a grammar system.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we introduced a formalism that integrates a grammar with constraints, Fuzzy Property Grammar, on a Grammar System model: Fuzzy Property Grammar System. This framework might be applied to the formal characterization of evaluative expressions used in hate speech and might contribute to the automatic detection of verbal violence.

FPGS considers different grammars per domain, representing the difference between a plain insult as an evaluation and an insult with a metaphor. Using FPGS shows no conflict in the grammar system because of different outcomes on different grammars. The pragmatic grammar can be satisfied, while the syntax and the semantics are not.

Our formal model might be applicable to hate speech that involves an explicit insult as an evaluation with negative sentiment or an implicit insult with a metaphor as an evaluation.

The results of our proof of concept, both the annotation and the examples of formal treatment of expressions, show that plain insults include only three categories: (1) intelligence, (2) judgment, and (3) esteem. This outcome may be due to cultural factors. We could speculate that in Spanish culture, it is more offensive to verbally attack the referent as “inferior” by “evaluating” or “accusing” them of lacking intelligence or having immoral attitudes through society’s perspective. In contrast, metaphors have a more dispersed meaning because of this nonconventionlization. Their implicitness can play an essential role in meaning expansion: Depending on the context, evaluative heads of metaphors mark specific evaluations. Each metaphor considers more than one tag, which significantly differs from plain insults, which only receive one evaluative tag. Although examples such as “pork” or “rat” can be considered almost conventionalized, they only include two tags, they can be used in different situations, and another evaluation can be inferred.

On the other hand, plain insults only bear one evaluative tag. This issue is the main difference between a metaphor and a plain insult. Such a claim coincides with linguistic theory, since metaphors are cancelable and plain insults are not. The relationship between the two could be gradual or fuzzy if we want to consider that the fewer tags a metaphor has, the more conventionalized it is and the closer it is to the plain insult.

Because of the annotation effort of this research, any lexical item tagged with a linguistic semantic variable presented in this work can go under the same formal treatment as in our examples. It is only necessary to consider if a lexical item is the bearer of only an LSV tag in the semantic domain or, on the contrary, has an LSV tag in the pragmatic domain (metaphor).

One of the significant criticisms our approach could receive is that a very powerful lexicon is needed. In the end, the lexicon provides the knowledge of which words are evaluative heads or not, as well as which grammar is used. We wanted to mitigate this by including the constraint rules of and for the sake of generalization.

The future work of integrating a linguistic grammar system with a Fuzzy Property Grammar involves creating a computational model for testing the computational viability of its architecture and, secondly, designing a methodology for semiautomatic or automatic annotation of the semantic and pragmatic tags.

One of the issues with Fuzzy Property Grammars concerns the difficulty of extracting constraints, since they have to be extracted by experts with the support of computational tools. However, no algorithm can still automatically induce a Fuzzy Property Grammar, not even for the syntactic domain. Consequently, it would be interesting to initiate a project using methods to check if they can improve the automatization of our model by fuzzy neuronal networks, XAI (explainable artificial intelligence), or even GPT-3.5 by starting with a small semantic topic and expanding it from there.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T.-U., M.D.J.-L. and S.C.-M.; formal analysis, A.T.-U. and M.D.J.-L.; writing—original draft, A.T.-U., M.D.J.-L. and S.C.-M.; writing—review and editing, A.T.-U., M.D.J.-L. and S.C.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by the project PID2020-120158GB-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fortuna, P.; Nunes, S. A Survey on Automatic Detection of Hate Speech in Text. ACM Comput. Surv. 2018, 51, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, P.; Soler, J.; Wanner, L. Toxic, Hateful, Offensive or Abusive? What Are We Really Classifying? An Empirical Analysis of Hate Speech Datasets. In Proceedings of the 12th Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, European Language Resources Association, Marseille, France, 11–16 May 2020; pp. 6786–6794. [Google Scholar]

- Vidgen, B.; Harris, A.; Nguyen, D.; Tromble, R.; Hale, S.; Margetts, H. Challenges and frontiers in abusive content detection. In Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Abusive Language Online; Association for Computational Linguistics, Firenze, Italy, 1–2 August 2019; pp. 80–93. [Google Scholar]

- Poletto, F.; Basile, V.; Sanguinetti, M.; Bosco, C.; Patti, V. Resources and benchmark corpora for hate speech detection: A systematic review. Lang. Resour. Eval. 2021, 55, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboada, M. Sentiment Analysis: An Overview from Linguistics. Annu. Rev. Linguist. 2016, 2, 325–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. Sentiment Analysis: Mining Opinions, Sentiments and Emotions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Taboada, M.; Brooke, J.; Tofiloski, M.; Voll, K.; Stede, M. Lexicon-based methods for sentiment analysis. Comput. Linguist. 2011, 37, 267–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccianella, S.; Esuli, A.; Sebastiani, F. Sentiwordnet 3.0: An enhanced lexical resource for sentiment analysis and opinion mining. In Proceedings of the LREC, Valletta, Malta, 17–23 May 2010; Volume 10, pp. 2200–2204. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmatian, F.; Sohrabi, M.K. A survey on classification techniques for opinion mining and sentiment analysis. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2019, 52, 1495–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Vishwakarma, D.K. Sentiment analysis using deep learning architectures: A review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2020, 53, 4335–4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socher, R.; Perelygin, A.; Wu, J.; Chuang, J.; Manning, C.D.; Ng, A.Y.; Potts, C. Recursive deep models for semantic compositionality over a sentiment treebank. In Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Seattle, WA, USA, 18–21 October 2013; pp. 1631–1642. [Google Scholar]

- Novák, V. The Concept of Linguistic Variable Revisited. In Recent Developments in Fuzzy Logic and Fuzzy Sets; Sugeno, M., Kacprzyk, J., Shabazova, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, L.; Novák, V. Forecasting seasonal time series based on fuzzy techniques. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2019, 361, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, V. Fuzzy Natural Logic: Towards Mathematical Logic of Human Reasoning. In Fuzzy Logic: Towards the Future; Seising, R., Trillas, E., Kacprzyk, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 137–165. [Google Scholar]

- Torrens-Urrutia, A.; Novák, V.; Jiménez-López, M.D. Describing Linguistic Vagueness of Evaluative Expressions Using Fuzzy Natural Logic and Linguistic Constraints. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escandell, M.V. Introducción a la Pragmática; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Salomaa, A. Formal Languages; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Rozenberg, G.; Salomaa, A. Handbook of Formal Languages; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Csuhaj-Varjú, E.; Dassow, J.; Kelemen, J.; Păun, G. Grammar Systems: A Grammatical Approach to Distribution and Cooperation; Gordon and Breach: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Torrens-Urrutia, A.; Novák, V.; Jiménez-López, M.D. Fuzzy Property Grammars for Gradience in Natural Language. Mathematics 2023, 11, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csuhaj-Varjú, E.; Dassow, J. On Cooperating/Distributed Grammar Systems. J. Inf. Process. Cybern. (EIK) 1990, 26, 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Păun, G.; Sântean, L. Parallel Communicating Grammar Systems: The Regular Case. Ann. Univ. Buchar.-Math.-Inform. Ser. 1989, 38, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Novák, V. A Comprehensive Theory of Trichotomous Evaluative Linguistic Expressions. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2008, 159, 2939–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, V. Mining information from time series in the form of sentences of natural language. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2016, 78, 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, V. Fuzzy Logic in Natural Language Processing. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems, Naples, Italy, 9–12 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Novák, V. Evaluative linguistic expressions vs. fuzzy categories? Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2015, 281, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, V. Mathematical Fuzzy Logic: From Vagueness to Commonsese Reasoning. In Retorische Wissenschaft: Rede und Argumentation in Theorie und Praxis; Kreuzbauer, G., Gratzl, N., Hielb, E., Eds.; LIT-Verlag: Wien, Austria, 2008; pp. 191–223. [Google Scholar]

- Novák, V.; Perfilieva, I.; Dvorak, A. Insight into Fuzzy Modeling; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Novák, V. Fuzzy Natural Logic: Theory and Applications. In Proceedings of the Fuzzy Sets and Their Applications FSTA 2016, Liptovský Ján, Slovak Republic, 24–29 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Blache, P. Representing syntax by means of properties: A formal framework for descriptive approaches. J. Lang. Model. 2016, 4, 183–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blache, P. Estimating Constraint Weights from Treebanks. In Proceedings of the CSLP-2012, Orléans, France, 13–14 September 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Blache, P. A robust and efficient parser for non-canonical inputs. In Proceedings of the ROMAND-06, Sydney, Australia, 17–16 July 2006; pp. 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Blache, P. Property grammars: A fully constraint-based theory. In Constraint Solving and Language Processing; Christiansen, H., Skadhauge, P.R., Villadsen, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; Volume LNAI 3438, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Blache, P. Property grammars and the problem of constraint satisfaction. In Proceedings of the ESSLLI 2000 Workshop on Linguistic Theory and Grammar Implementation, Birmingham, UK, 6–18 August 2000; pp. 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Torrens-Urrutia, A.; Jiménez-López, M.D.; Brosa-Rodríguez, A.; Adamczyk, D. A Fuzzy Grammar for Evaluating Universality and Complexity in Natural Language. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Universal Dependency Corpora. Available online: https://universaldependencies.org/ (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Blache, P.; Rauzy, S.; Montcheuil, G. MarsaGram: An excursion in the forests of parsing trees. In Proceedings of the Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, Portorož, Slovenia, 23–28 May 2016; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Grice, H.P. Meaning. Philos. Rev. 1957, 66, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zufferey, S.; Moeschler, J.; Reboul, A. Implicatures; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Frege, G. Estudios Sobre Semántica; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 1892. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. The Oxford Handbook of Pragmatics; Oxford handbooks in linguistics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grice, P. Studies in the Way of Words; Harvard University Press: Harvard, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barrero, T. Razón Intención y Significado: Una Lectura Contemporánea de Paul Grice; Universidad de los Andes: Bogotá, CO, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. Metáforas de la Vida Cotidiana; Serie mayor, Ediciones Cátedra; Colección Teorema: Madrid, Spain, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Khatin-Zadeh, O.; Khoshsima, H.; Banaruee, H. Representational Transformation: A Facilitative Process of Understanding. Int. J. Brain Cogn. Sci. 2017, 2017, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatin-Zadeh, O.; Vahdat, S. Abstract and concrete representations in structure-mapping and class-inclusion. Cogn. Linguist. Stud. 2015, 2, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-López, M.D. A grammar systems approach to natural language grammar. Linguist. Philos. 2006, 29, 419–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).