Predicting the Fatigue Life of a Commercial Vehicle X-EPS Steering Gear with a Rigid–Flexible Coupling Dynamics Method

Abstract

:1. Introduction

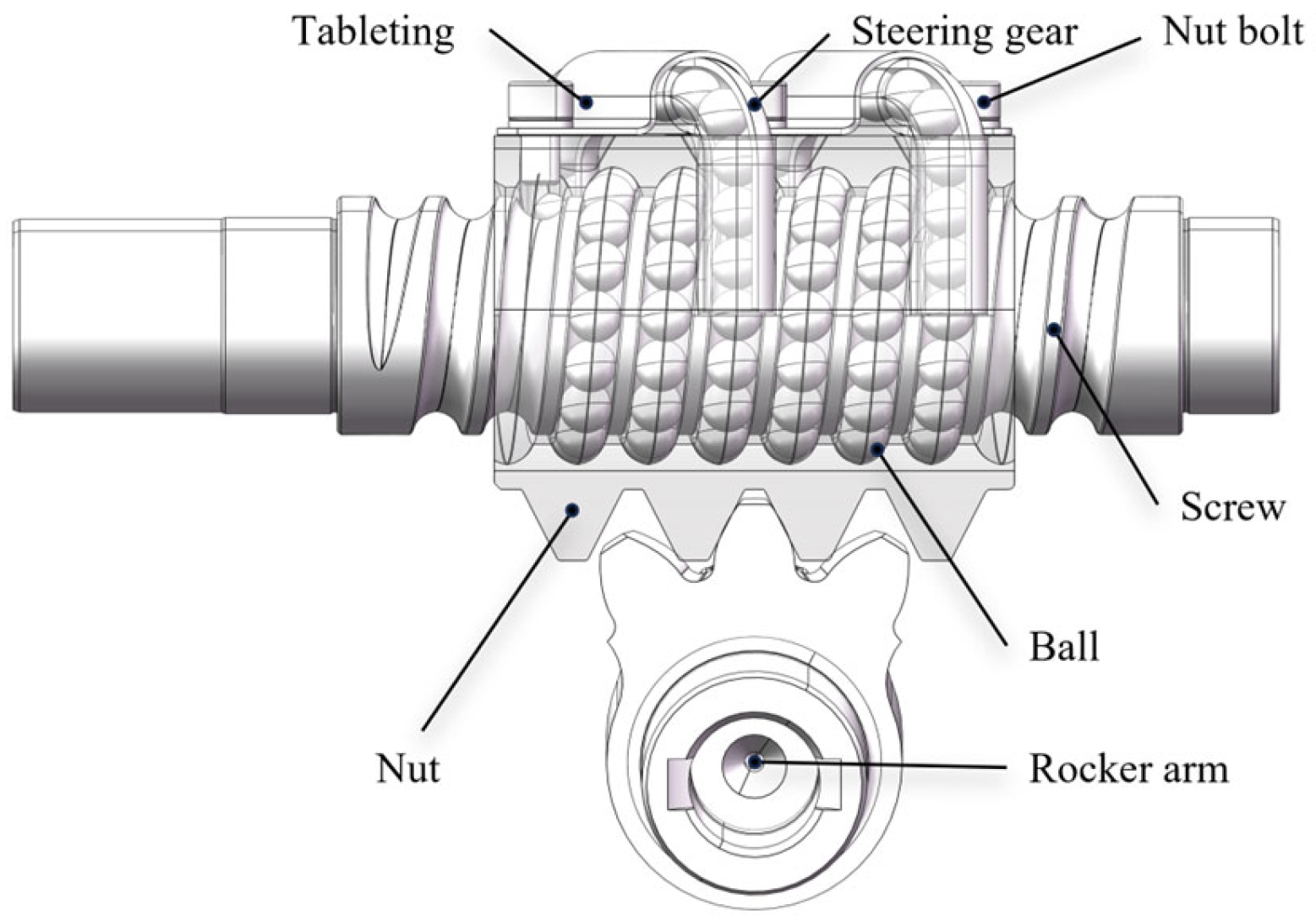

2. Main Parameters of XEPS Steering Gear

3. Rigid–Flexible Coupling Dynamic Analysis

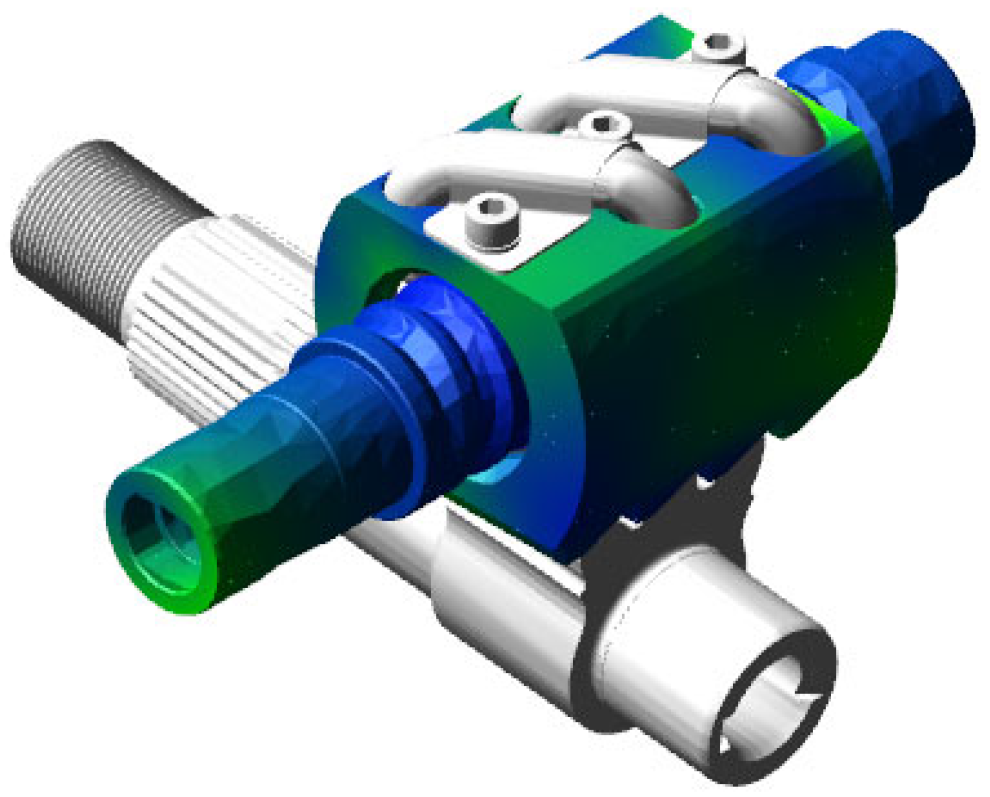

3.1. Establishment of Dynamic Model

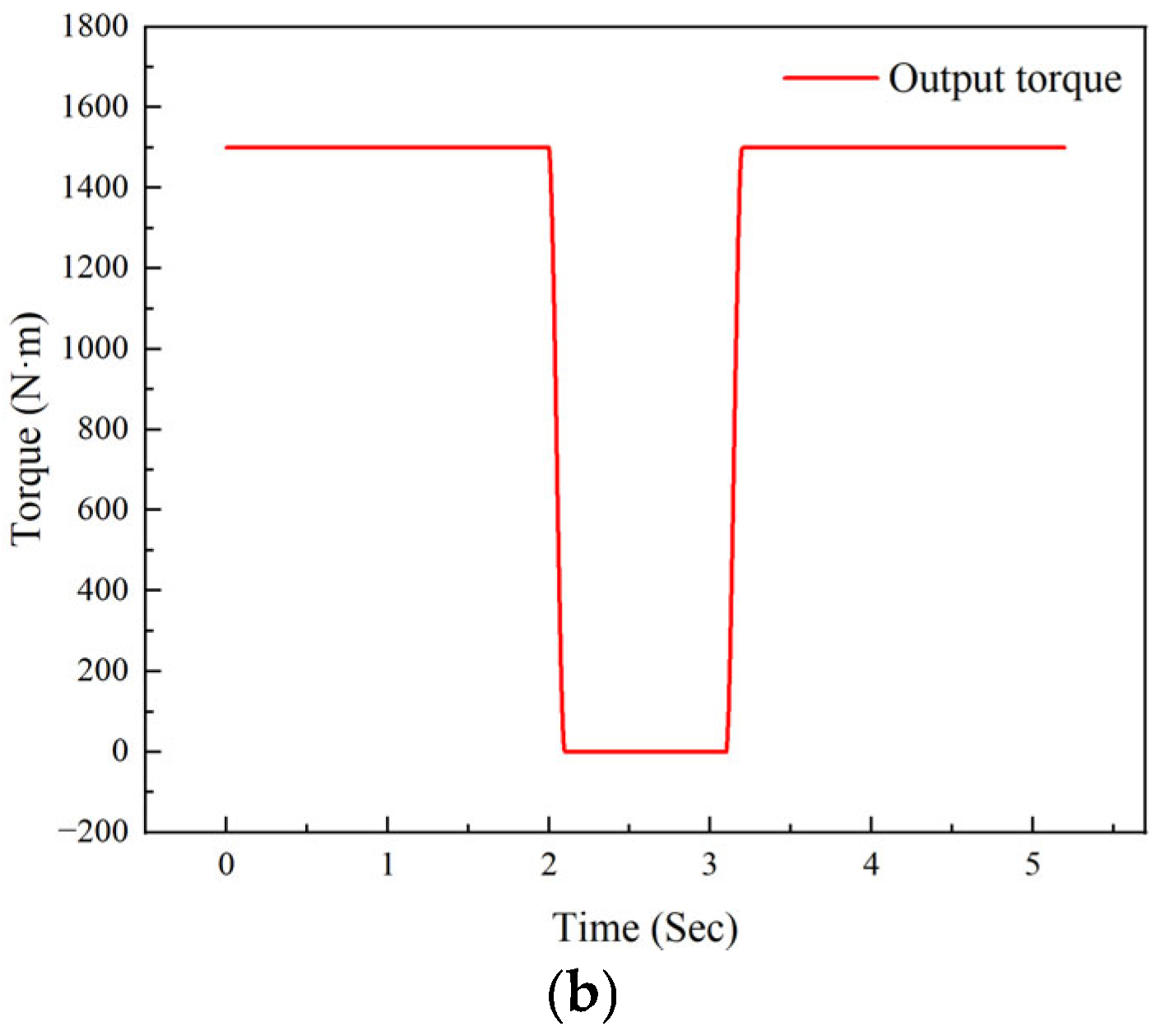

3.2. Working Condition Analysis

3.3. Constraint Setup

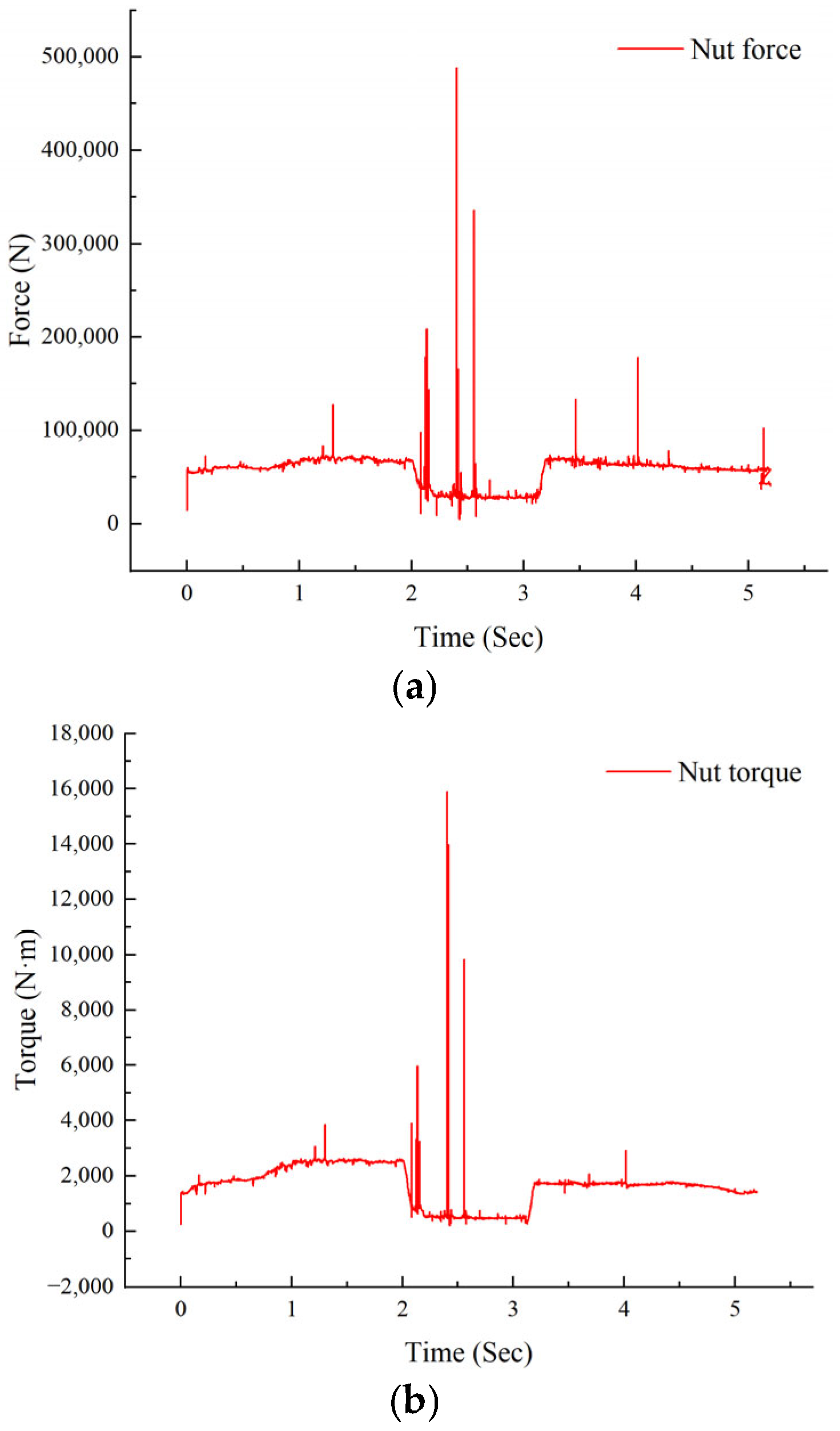

3.4. Dynamic Response Results

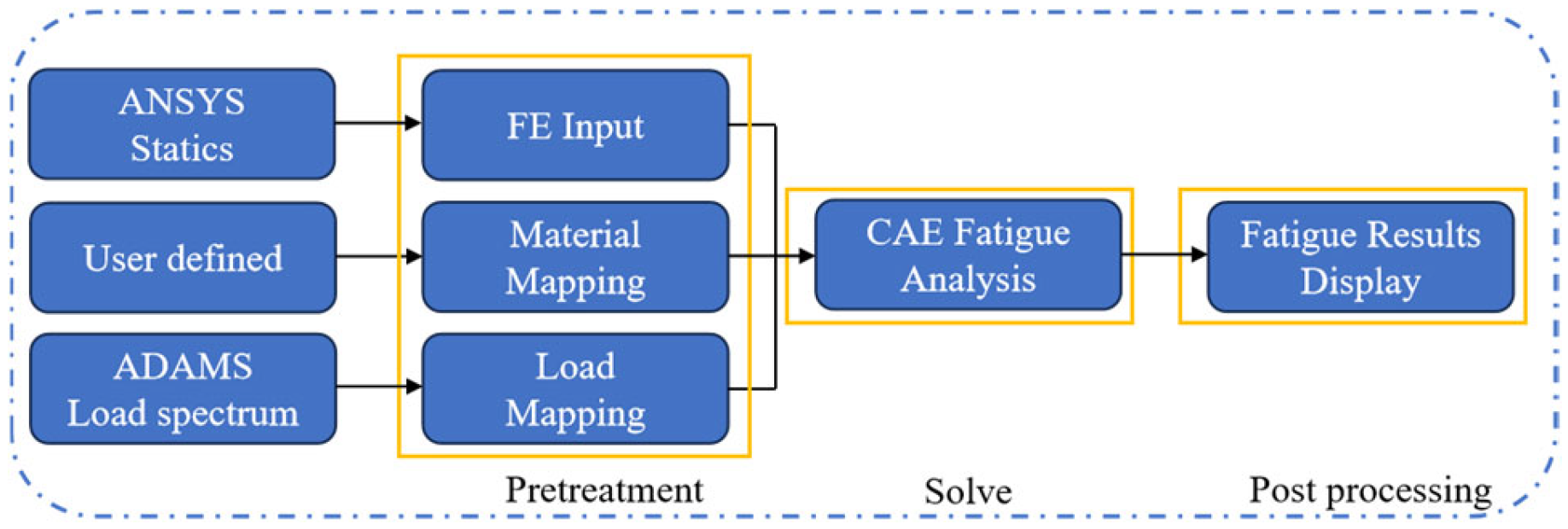

4. Fatigue Life Analysis of XEPS Steering Gear

4.1. Finite Element Model

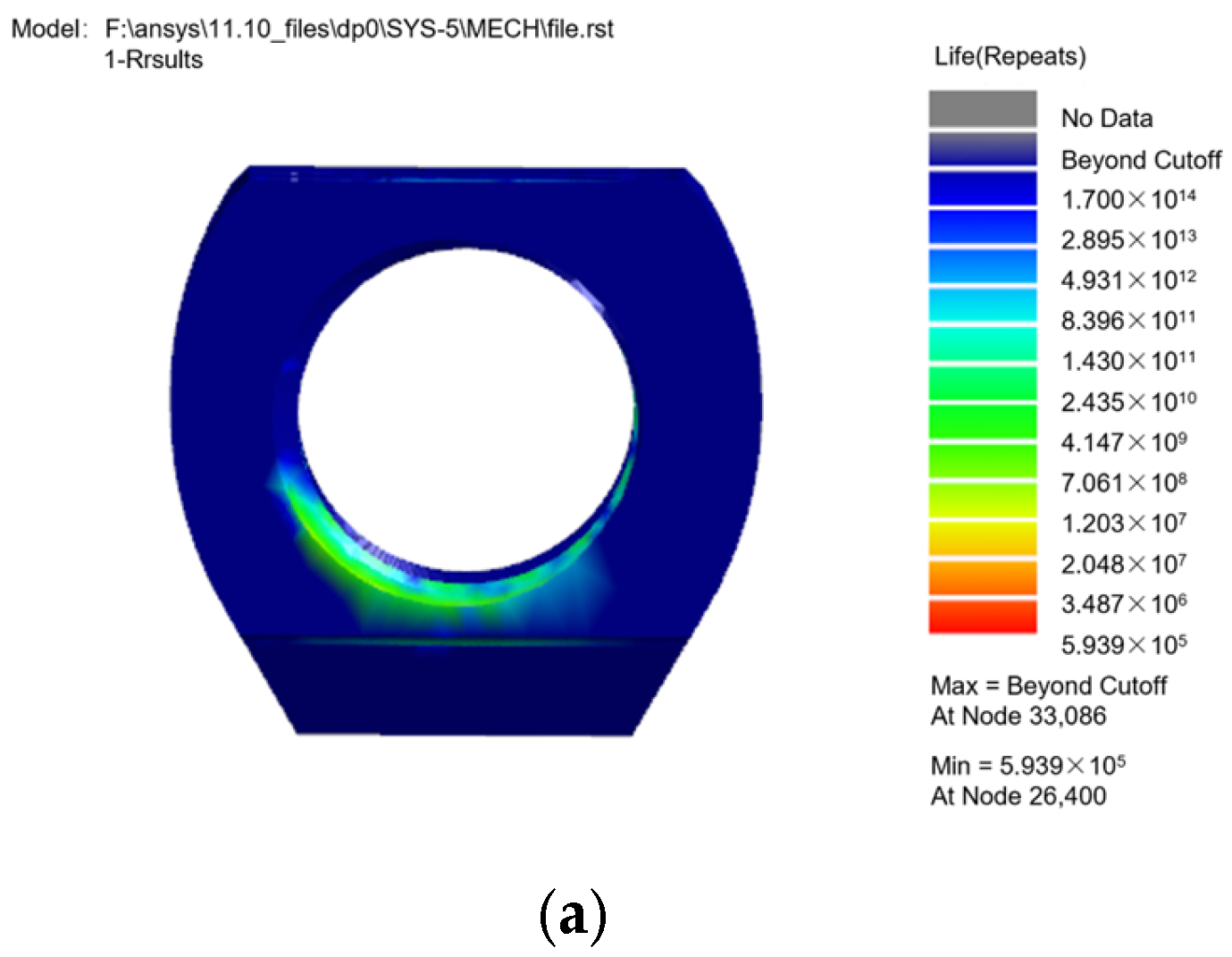

4.2. Fatigue Life Analysis

4.3. Parameter Definition

4.4. Research Result Analysis

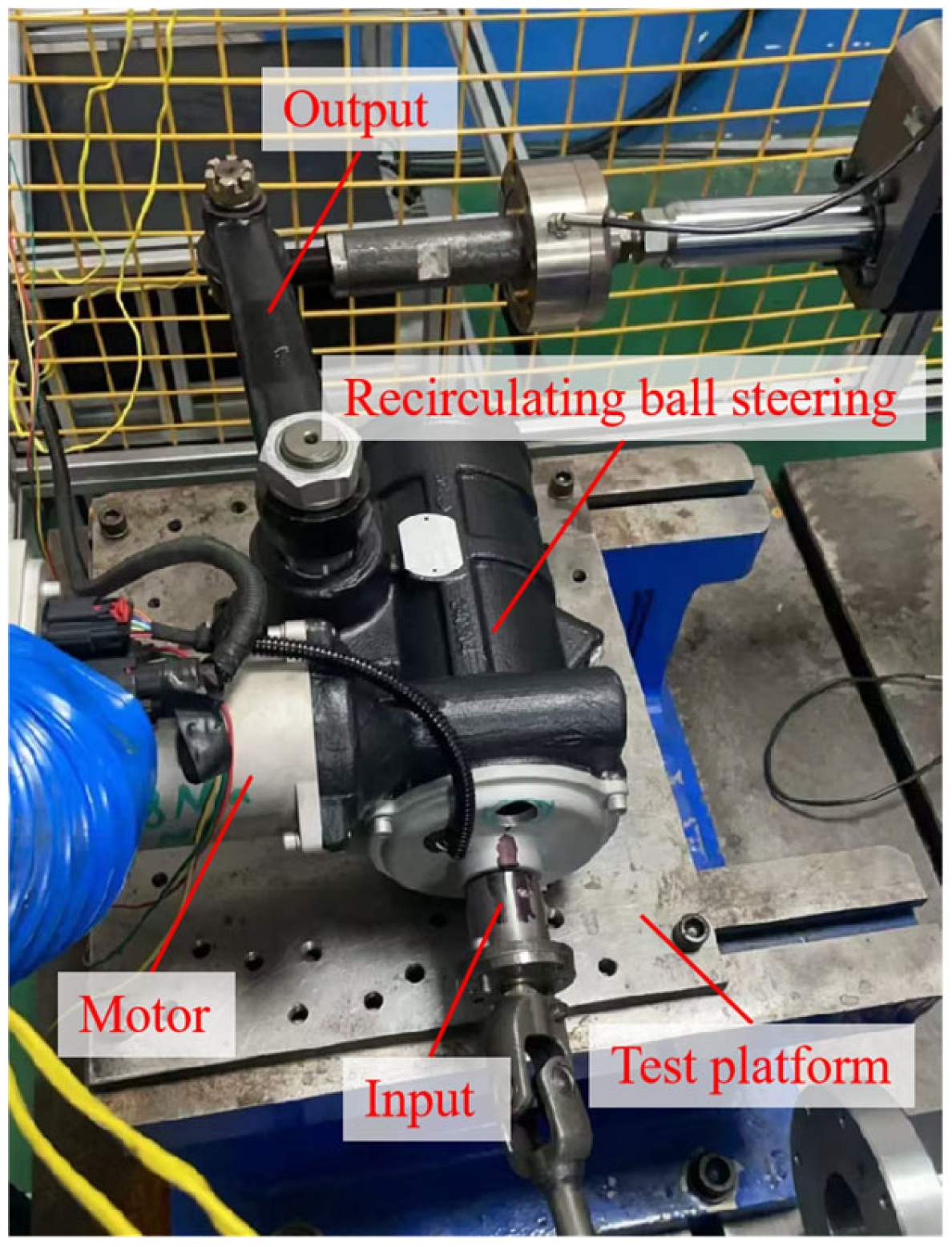

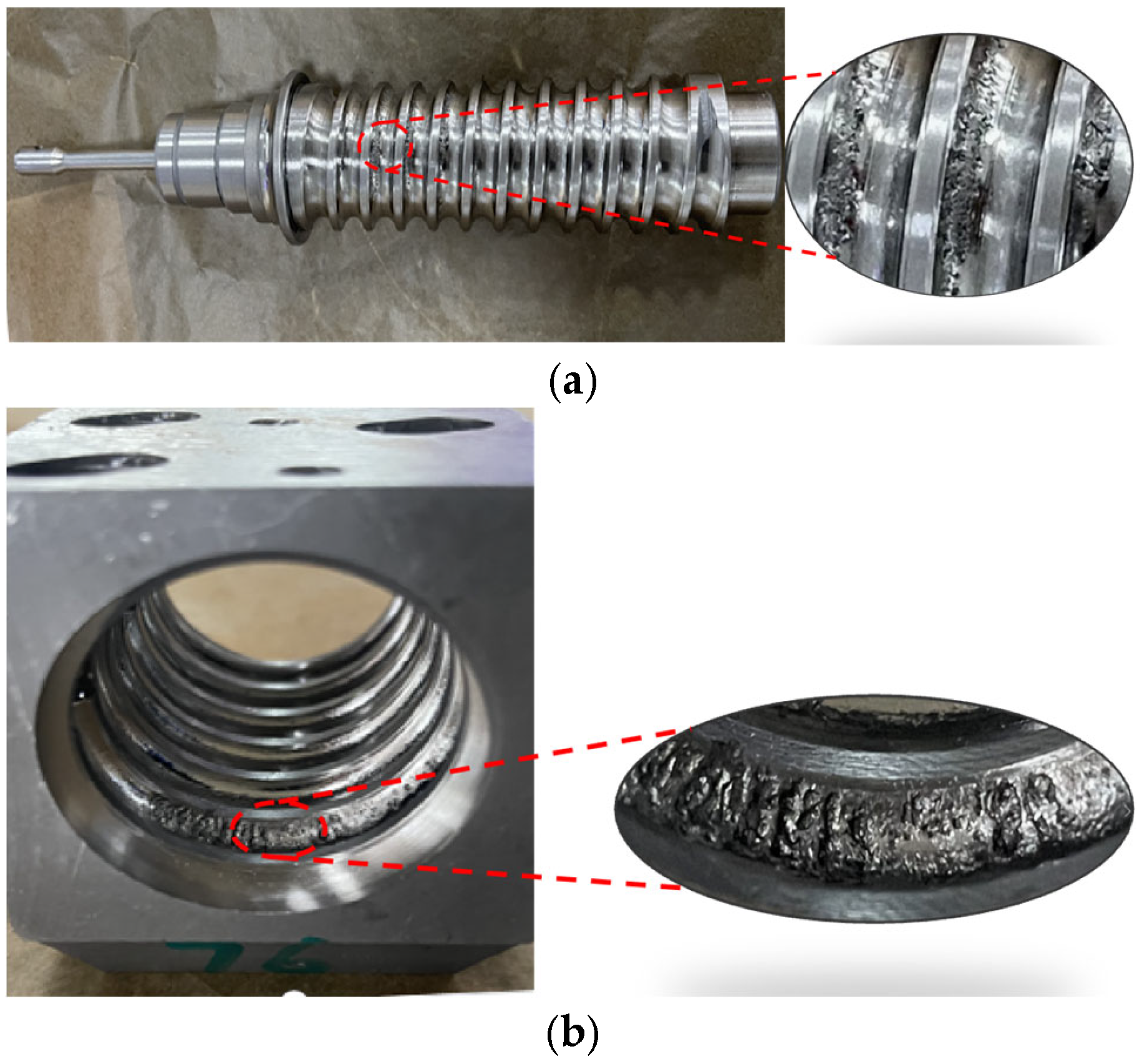

4.5. Bench Tests

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, B. Structural Design and Optimization of Light Truck Steering System. Master’s Thesis, Dalian Jiaotong University, Dalian, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, P.; Gong, W.; Xie, G.; Zhong, L.; Liao, J.; Li, G. Control Strategy of Rocker Shaft assisted circulating Ball EPS system. J. Southwest Univ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 38, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Li, Z.Z.; Tian, H.B. A control and compensation strategy of the electric power recirculating ball steering system. Comput. Eng. Sci. 2020, 42, 138. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.-J.; Zhou, X. Analysis on influencing factors of assist characteristic curve of circulating ball steering gear. Hydraul. Pneum. 2022, 46, 160–168. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Wang, L.-Z.; Chen, C.; Yin, Z.; Su, R.; Chen, X. Finite element Analysis of key parts of Automobile circulating Ball steering Gear. Pract. Technol. Automob. 2020, 45, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolino, A.; Sorli, M.; De Martin, A. Performance evaluation of a Ball Screw mechanism through a multibody dynamic model. Mater. Res. Proc. 2023, 26, 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, X. Stress and Fatigue Analysis of Circulating Ball Power Steering Gear. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, L.; Lu, C.; Chen, S.; Wang, W. Study on Load Distribution and Fatigue Elastic Life of Ball Screw under Ultimate Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojjati-Talemi, R.; Abdel Wahab, M. Fretting fatigue crack initiation lifetime predictor tool: Using damage mechanics approach. Tribol. Int. 2013, 60, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferjaoui, A.; Yue, T.; Abdel Wahab, M.; Hojjati-Talemi, R. Prediction of fretting fatigue crack initiation in double lap bolted joint using Continuum Damage Mechanics. Int. J. Fatigue 2015, 73, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Biswas, R.; Poh, L.H.; Abdel Wahab, M. Fretting fatigue stress analysis in heterogeneous material using direct numerical simulations in solid mechanics. Tribol. Int. 2017, 109, 124–132. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.; Zhou, X.-Y. Effect of semi-active suspension on vehicle durability. J. Tongji Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 50, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pichandi, M.; Mohan, B.; Jagadeesh, S.; Balaji, S. Conventional Four-bar Linkage Steering System Adoption for Underslung Front Suspension. ARAI J. Mobil. Technol. 2022, 2, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Y.-J.; Zhang, S.-H.; Yang, J.; Dong, Q. Study on fatigue Life of a medium truck Cab based on Virtual iteration and finite element Theory. Chin. Mech. Eng. Process 2018, 29, 1588–1595. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Wei, Y.; Ju, C.; He, S. Multiobjective Optimization of Vehicle Handling and Stability Based on ADAMS. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 3245251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok Kumar, S.C.; Erikmats, E. Modelling and Control of Active Power Steering Systems for Heavy Trucks. Master’s Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kuris, S.; Gungor, E.; Deniz, A.; Uysal, G.; Aykent, B. Kinematics and Compliance Analysis of a 3.5 Tonne Load Capacity Independent Front Suspension for LCV; No. 2019-01-0935; SAE Technical Paper; SAE: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- You, Z.; Li, R.; Liu, Q. Motor Control Strategy of Recirculating-Ball EHPS System for Bus Under Multi Working Conditions. Int. J. Simul.—Syst. Sci. Technol. 2015, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.-Q.; Shi, D.-W. Dynamic simulation and fatigue life prediction of transmission system of vertical ship lift. J. Wuhan Univ. (Eng. Ed.) 2016, 49, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, K.; Cheng, Y. Research on Parameter selection of Simulation calculation of Gear Meshing Force. Comput. Simul. 2002, 19, 87–88. [Google Scholar]

- QC/T 29096-2010; Performance Requirements and Test Methods of Automobile Steering Rod Ball Head Assembly. Ministry of Industry and Information Technology: Beijing, China, 2010.

- Ma, J.; Wang, Z.T.; Zhou, D.; Liao, L.H.; Huang, Z. Analysis of wind-induced vibration and fatigue effects of a typical tower crane. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. 2014, 48, 804–808. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, N.; Han, C.-R. Fatigue life analysis of tower crane jib based on ADAMS rigid-flexible coupling model. Mech. Electr. Program 2021, 38, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Kobelev, V. Effects of Mean Stress and Multiaxial Loading on the Fatigue Life of Springs. Eng 2023, 4, 1684–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Huang, J. Analytical analysis and oscillation control of payload twisting dynamics in a tower crane carrying a slender payload. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 158, 107763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Gear fan module/mm | 6.0 |

| Rocker arm diameter/mm | 41 |

| Nut length/mm | 81 |

| Screw outer diameter/mm | 37 |

| Steel ball diameter/mm | 8 |

| Pitch/mm | 11 |

| Gear fan pressure angle | 26.85° |

| Gear fan rake angle | 6.5° |

| Number of teeth on gear fan | 3 |

| Material | 20CrMnTi | GCr15 |

|---|---|---|

| Density/(kg·m−3) | 7860.0 | 7830.0 |

| Young’s modulus/GPa | 2.12 | 2.19 |

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.289 | 0.3 |

| Yield strength/MPa | 835 | 518 |

| Compressive strength/MPa | 1080 | 861 |

| Serial Number | Constrain Assembly | Constraint Type |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Screw, ground | Revolute joint |

| 2 | Nut, ground | Prismatic joint |

| 3 | Rocker arm, ground | Revolute joint |

| 4 | Nut, return device | Fixed joint |

| 5 | Nut, M6 bolt | Fixed joint |

| 6 | Nut, pressing tablet | Fixed joint |

| Component | Simulation/Time | Experimental/Time | Error/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screw | 102,800 | 106,589 | 3.68 |

| Nut | 296,950 | 283,643 | 4.48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, F.; Fu, Z.; Qiu, B.; Si, C.; Zhu, Q.; Feng, C.; Sun, X.; Liang, H.; Yang, L. Predicting the Fatigue Life of a Commercial Vehicle X-EPS Steering Gear with a Rigid–Flexible Coupling Dynamics Method. Machines 2025, 13, 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13030218

Chen F, Fu Z, Qiu B, Si C, Zhu Q, Feng C, Sun X, Liang H, Yang L. Predicting the Fatigue Life of a Commercial Vehicle X-EPS Steering Gear with a Rigid–Flexible Coupling Dynamics Method. Machines. 2025; 13(3):218. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13030218

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Feng, Zhiquan Fu, Baoxiang Qiu, Chenfeng Si, Qizhang Zhu, Chenli Feng, Xiaoqing Sun, Huafang Liang, and Lai Yang. 2025. "Predicting the Fatigue Life of a Commercial Vehicle X-EPS Steering Gear with a Rigid–Flexible Coupling Dynamics Method" Machines 13, no. 3: 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13030218

APA StyleChen, F., Fu, Z., Qiu, B., Si, C., Zhu, Q., Feng, C., Sun, X., Liang, H., & Yang, L. (2025). Predicting the Fatigue Life of a Commercial Vehicle X-EPS Steering Gear with a Rigid–Flexible Coupling Dynamics Method. Machines, 13(3), 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13030218