The Development of a Personalized Symptom Management Mobile Health Application for Persons Living with HIV in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

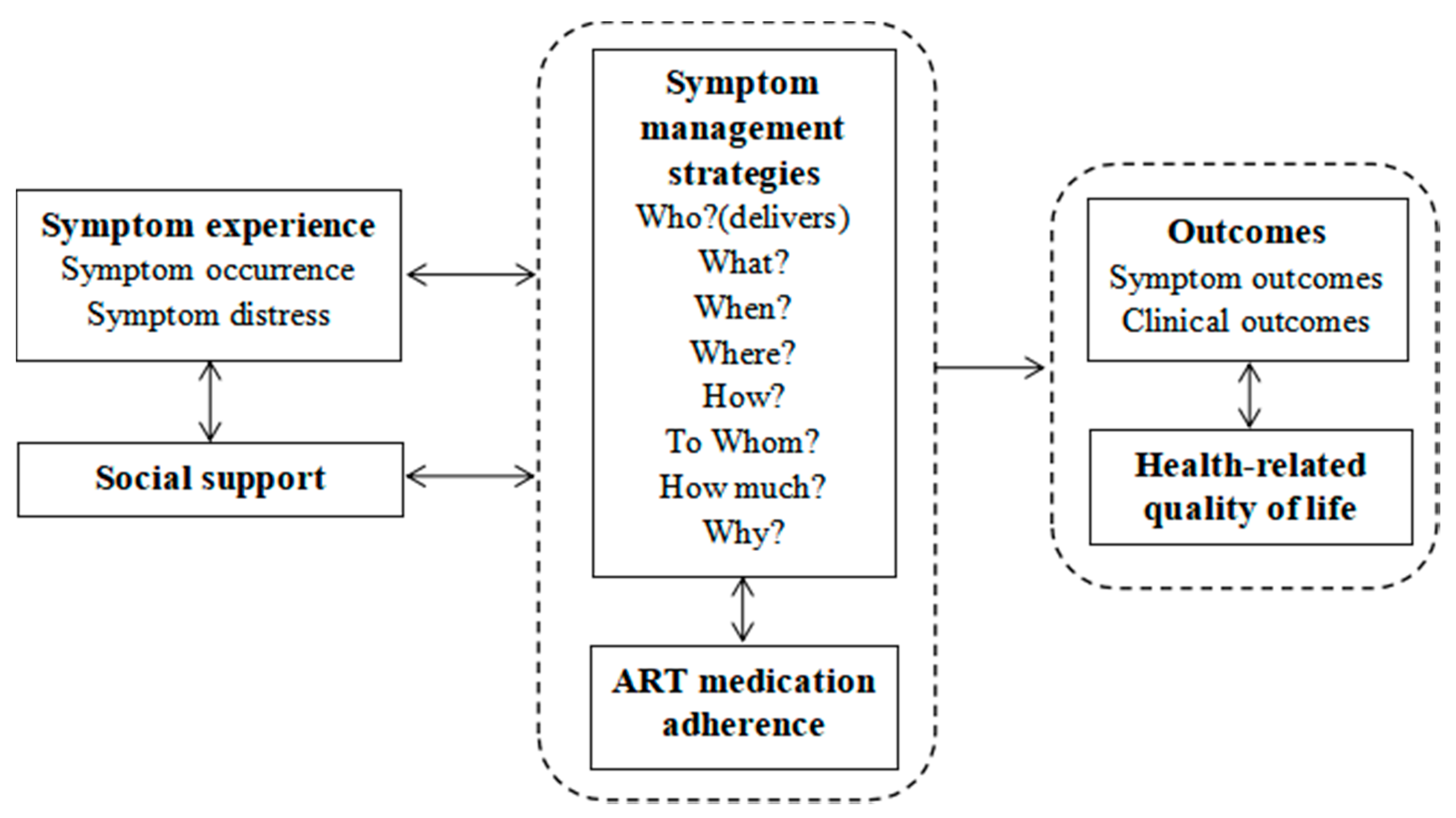

2. Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Drafting the Structure and Content of the App

3.2. Group Discussion and Written Feedback from the Multidisciplinary Research Team

4. Results

4.1. Suggestions and Feedback from the Group Discussion

4.2. Structure and Key Functions of the App

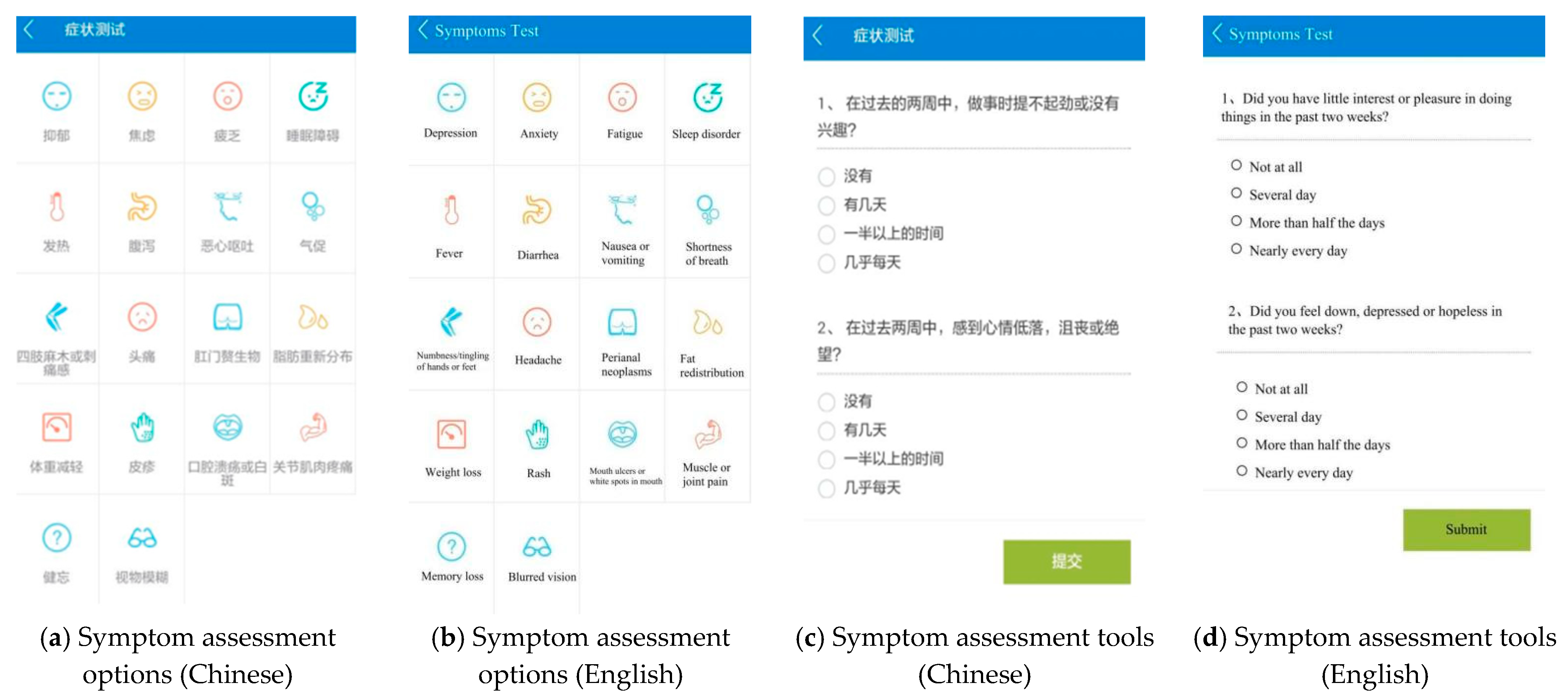

4.2.1. Self-Assessment Module

4.2.2. Health Tracking Module

4.2.3. Coping Strategy Module

4.2.4. Obtaining Support Module

4.2.5. Other Modules

4.2.6. Web-Based Administration Portal Functions

- The user management function manages all registered account information.

- The information publishing function can push or edit health education content.

- The content management function can summarize user assessment data and provide reminders for outliers. Case managers contact and provide personalized interventions based on their lab tests.

- The Q&A function can answer user questions.

- Other functions include basic statistical functions such as analyzing users’ login numbers and viewing each module’s number.

4.3. Privacy and Confidentiality

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yoshimura, K. Current status of HIV/AIDS in the ART era. J. Infect. Chemother. 2017, 23, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román, E.; Chou, F.-Y. Development of a Spanish HIV/AIDS symptom management guidebook. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2011, 22, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Li, H.-W.; Bao, M.-J.; Zhang, L.; Zha, L.-J.; Hou, X.-H.; Lu, H.-Z. The implementation and evaluation of HIV symptom management guidelines: A preliminary study in China. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2018, 5, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willard, S.; Holzemer, W.L.; Wantland, D.J.; Cuca, Y.P.; Kirksey, K.M.; Portillo, C.J.; Corless, I.B.; Rivero-Méndez, M.; Rosa, M.E.; Nicholas, P.K.; et al. Does “asymptomatic” mean without symptoms for those living with HIV infection? AIDS Care. 2009, 21, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namisango, E.; Harding, R.; Katabira, E.T.; Siegert, R.J.; Powell, R.A.; Atuhaire, L.; Moens, K.; Taylor, S. A novel symptom cluster analysis among ambulatory HIV/AIDS patients in Uganda. AIDS Care. 2015, 27, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.-T.; Shiu, C.; Yang, J.P.; Tun, M.M.M.; Zhang, L.; Wang, K.; Chen, L.-C.; Aung, M.N.; Lu, H.; Zhao, H. Tobacco use and HIV symptom severity in Chinese people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2020, 32, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.A.; Gay, C.; Portillo, C.J.; Coggins, T.; Davis, H.; Pullinger, C.R.; Aouizerat, B.E. Symptom experience in HIV-infected adults: A function of demographic and clinical characteristics. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2009, 38, 882–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, B.; Vincent, W.; Meyer, J.P.; Kershaw, T.; Sikkema, K.J.; Heckman, T.G.; Hansen, N.B. Depressive symptoms, physical symptoms, and health-related quality of life among older adults with HIV. Qual. Life Res. 2019, 28, 3313–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ji, G.; Lin, C.; Liang, L.J.; Lan, C.W. Antiretroviral therapy initiation following policy changes: Observations from China. Asia-Pac. J. Public Health. 2016, 28, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saag, M.S.; Gandhi, R.T.; Hoy, J.F.; Landovitz, R.J.; Thompson, M.A.; Sax, P.E.; Smith, D.M.; Benson, C.A.; Buchbinder, S.P.; del Rio, C.; et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults: 2020 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2020, 324, 1651–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AIDS and Hepatitis C Professional Group, Society of Infectious Disease, Chinese Medical Association; Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of HIV/AIDS (2018). Chin. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 57, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S.; Ahmadi, S.; Rahmati, J.; Hosseinifard, H.; Dehnad, A.; Aryankhesal, A.; Shabaninejad, H.; Ghasemyani, S.; Alihosseini, S.; Bragazzi, N.L.; et al. Global prevalence of depression in HIV/AIDS: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care. 2019, 9, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Luo, D.; Liu, Y.; Silenzio, V.M.; Xiao, S. The mental health of people living with HIV in China, 1998–2014: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spirig, R.; Moody, K.; Battegay, M.; De Geest, S. Symptom management in HIV/AIDS: Advancing the conceptualization. ANS Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2005, 28, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; Chen, W.-T.; Lu, H.; Zhu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Bao, M. Unmet needs of symptom management and associated factors among the HIV-positive population in Shanghai, China: A cross-sectional study. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2020, 54, 151283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Guo, M.; Williams, A.B. Urban and rural differences: Unmet needs for symptom management in people living with HIV in China. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care. 2019, 30, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ITU. Statistics. Available online: https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/stat/default.aspx (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- Baig, M.M.; GholamHosseini, H.; Connolly, M.J. Mobile healthcare applications: System design review, critical issues and challenges. Australas. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2015, 38, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnall, R.; Mosley, J.P.; Iribarren, S.J.; Bakken, S.; Carballo-Diéguez, A.; Brown, W., III. Comparison of a user-centered design, self-management app to existing mHealth apps for persons living with HIV. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2015, 3, e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnall, R.; Cho, H.; Mangone, A.; Pichon, A.; Jia, H. Mobile health technology for improving symptom management in low income persons living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2018, 22, 3373–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodd, M.; Janson, S.; Facione, N.; Faucett, J.; Froelicher, E.S.; Humphreys, J.; Lee, K.; Miaskowski, C.; Puntillo, K.; Rankin, S.; et al. Advancing the science of symptom management. J. Adv. Nurs. 2001, 33, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haute Autorité de Santé. Good Practice Guidelines on Health Apps and Smart Devices (Mobile Health or mHealth). 2016. Available online: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2017-03/dir1/good_practice_guidelines_on_health_apps_and_smart_devices_mobile_health_or_mhealth.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2016).

- Holzemer, W.L.; Hudson, A.; Kirksey, K.M.; Hamilton, M.J.; Bakken, S. The revised sign and symptom check-list for HIV (SSC-HIVrev). J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care. 2001, 12, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justice, A.C.; Holmes, W.; Gifford, A.L.; Rabeneck, L.; Zackin, R.; Sinclair, G.; Weissman, S.; Neidig, J.; Marcus, C.; Chesney, M.; et al. Development and validation of a self-completed HIV symptom index. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2001, 54 (Suppl. 1), S77–S90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Xing, W.; Guo, M.; Zhao, R.; Han, S.; Wu, B. Identifying symptom clusters among people living with HIV on antiretroviral therapy in China: A network analysis. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2019, 57, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L. Development of the HIV/AIDS Clinical Nursing Practice Guidelines; Fudan University: Shanghai, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The patient health questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Med. Care. 2003, 41, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Monahan, P.O.; Löwe, B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 146, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, R.; Ayatolahi Tafti, M.; Hoveidamanesh, S.; Ghanavati, R.; Pournik, O. Reflection on mobile applications for blood pressure management: A systematic review on potential effects and initiatives. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2018, 247, 306–310. [Google Scholar]

- Brzan, P.P.; Rotman, E.; Pajnkihar, M.; Klanjsek, P. Mobile applications for control and self management of diabetes: A systematic review. J. Med. Syst. 2016, 40, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, C. Telehealth, mobile applications, and wearable devices are expanding cancer care beyond walls. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 34, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, S.; Pei, Y.; Wang, L.; Hu, Y.; Qi, X.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, L.; Sun, W.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, B. The Development of a Personalized Symptom Management Mobile Health Application for Persons Living with HIV in China. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11050346

Han S, Pei Y, Wang L, Hu Y, Qi X, Zhao R, Zhang L, Sun W, Zhu Z, Wu B. The Development of a Personalized Symptom Management Mobile Health Application for Persons Living with HIV in China. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2021; 11(5):346. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11050346

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Shuyu, Yaolin Pei, Lina Wang, Yan Hu, Xiang Qi, Rui Zhao, Lin Zhang, Wenxiu Sun, Zheng Zhu, and Bei Wu. 2021. "The Development of a Personalized Symptom Management Mobile Health Application for Persons Living with HIV in China" Journal of Personalized Medicine 11, no. 5: 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11050346

APA StyleHan, S., Pei, Y., Wang, L., Hu, Y., Qi, X., Zhao, R., Zhang, L., Sun, W., Zhu, Z., & Wu, B. (2021). The Development of a Personalized Symptom Management Mobile Health Application for Persons Living with HIV in China. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 11(5), 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11050346