Recommendations for a Combined Laparoscopic and Transanal Approach in Treating Deep Endometriosis of the Lower Rectum—The Rouen Technique

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Surgical Procedure

- The procedure starts with the inspection of the pelvic cavity and identification of the anterior rectal wall (Figure 2a,b).

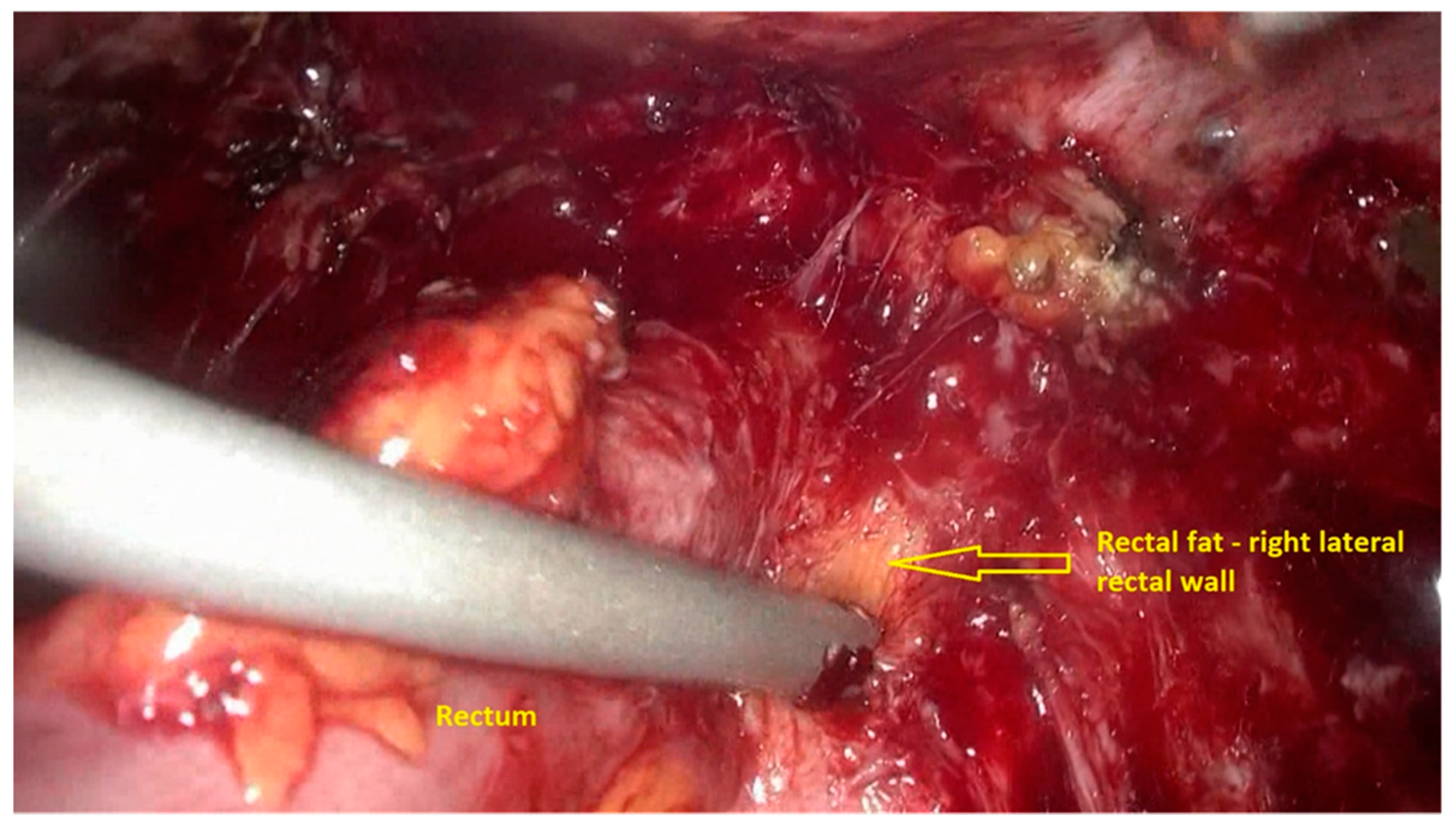

- The deep rectal spaces and rectovaginal septum surrounding the rectal nodule are opened in an anterolateral plan while staying connected to the levator ani muscle and with the preservation of fascia recti (Figure 3).

- After shaving, the rectum is completely freed. However, the shaved area might be rigid and infiltrated by endometriotic foci. When present, vaginal infiltration requires the excision of a patch of the posterior vaginal wall (Figure 6).

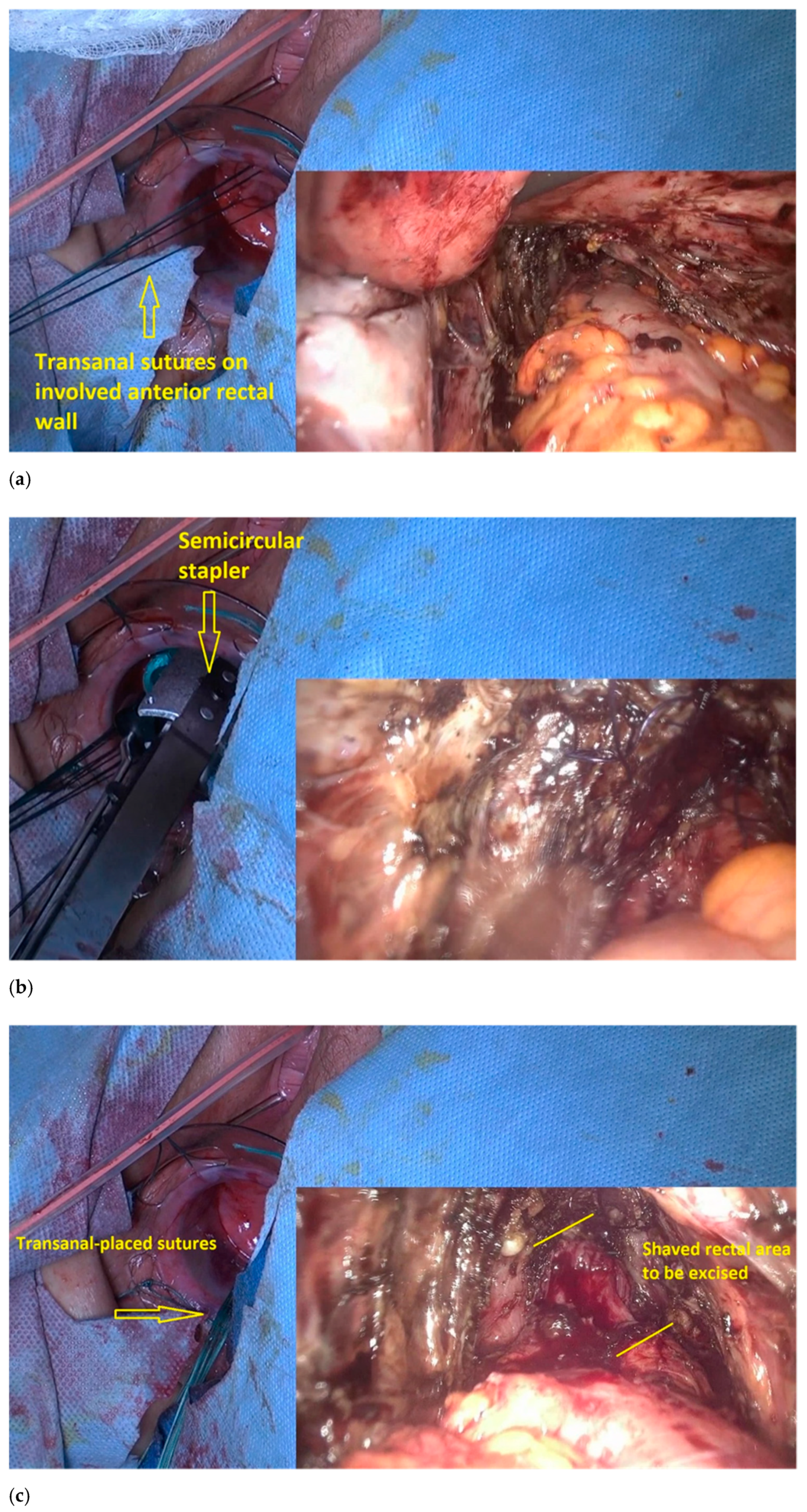

- The transanal dilatator is introduced to identify the shaved area. Once the shaved area is identified, with simultaneous transanal and laparoscopic views, 3 or 4 traction parachute sutures are placed in the middle and outside the shaved area (Figure 7a). The gynecologic surgeon uses laparoscopy to check the correct placement of the stitches and makes sure that the vagina is not caught in the stitching.

- The traction of the stitches induces the prolapse of the shaved rectum wall into the rectal lumen, which facilitates resection with the semicircular stapler, a device designed initially for excising a rectal prolapse (Figure 7b).

- A laparoscopically placed suture over the shaved rectal area assists the colorectal surgeon in correctly identifying the area to be resected (Figure 7c).

- The lubricated head of the stapler is introduced at the 3 o’clock position, with the jaws facing counterclockwise. The device is then rotated, and the shaved area is gently pulled inside the jaws until the surrounding normal bowel wall is set within the jaws.

- The stapler retaining pin is then applied, and the stapler is closed around the tissue for 15 s to maximize tissue compression; the staple is subsequently fired, and then removed. The stapler cartridge is then replaced, and the device is reintroduced into the rectum. This procedure is repeated until the shaved rectal area is completely resected. The stapled lines are inspected for bleeding. Reinforcement sutures are placed transanally, when necessary (Figure 7d).

- An air test is performed to ensure the integrity of the stapled line.

- A generous omentum flap is placed between the rectal and vaginal suture sites.

- When the procedure is associated with a large vaginal resection and a large low rectal excision, a diverting stoma on the sigmoid colon may be performed, based on the risk of developing fistula or anastomotic leakage.

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chapron, C.; Fauconnier, A.; Vieira, M.; Barakat, H.; Dousset, B.; Pansini, V.; Vacher-Lavenu, M.; Dubuisson, J. Anatomical distribution of deeply infiltrating endometriosis: Surgical implications and proposition for a classification. Hum. Reprod. 2003, 18, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koninckx, P.R.; Ussia, A.; Adamyan, L.; Wattiez, A.; Donnez, J. Deep endometriosis: Definition, diagnosis, and treatment. Fertil. Steril. 2012, 98, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Working group of ESGE, ESHRE, WES; Keckstein, J.; Becker, C.M.; Canis, M.; Feki, A.; Grimbizis, G.F.; Hummelshoj, L.; Nisolle, M.; Roman, H.; Saridogan, E.; et al. Recommendations for the surgical treatment of endometriosis. Part 2: Deep endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Open 2020, 2020, hoaa002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vercellini, P.; Viganò, P.; Somigliana, E.; Fedele, L. Endometriosis: Pathogenesis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laganà, A.S.; Garzon, S.; Götte, M.; Viganò, P.; Franchi, M.; Ghezzi, F.; Martin, D.C. The Pathogenesis of Endometriosis: Molecular and Cell Biology Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerby, B.L.; Kessler, H.; Falcone, T.; Milsom, J.W. Laparoscopic management of colorectal endometriosis. Surg. Endosc. 1999, 13, 1125–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, K.T.; Kuijpers, H.C.; Willemsen, W.N.; Bulten, H. Surgical treatment of symptomatic rectosigmoid endometriosis. Eur. J. Surg. 1996, 162, 139–141. [Google Scholar]

- Donnez, O.; Roman, H. Choosing the right surgical technique for deep endometriosis: Shaving, disc excision, or bowel resection? Fertil. Steril. 2017, 108, 931–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, L.C.; López-Garcia, E.; Schulze-Rath, R.; Rodríguez, L.A.G. Incidence, treatment and recurrence of endometriosis in a UK-based population analysis using data from The Health Improvement Network and the Hospital Episode Statistics database. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2017, 22, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Crosignani, P.G.; Abbiati, A.; Somigliana, E.; Viganò, P.; Fedele, L. The effect of surgery for symptomatic en-dometriosis: The other side of the story. Hum. Reprod. Update 2009, 15, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmertsen, K.J.; Laurberg, S. Low anterior resection syndrome score. Development and validation of s symptom-based scoring system for bowel dysfunction after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann. Surg. 2012, 255, 922–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridoux, V.; Roman, H.; Kianifard, B.; Vassilieff, M.; Marpeau, L.; Michot, F.; Tuech, J.-J. Combined transanal and laparoscopic approach for the treatment of deep endometriosis infiltrating the rectum. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 27, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnez, J.; Squifflet, J. Complications, pregnancy and recurrence in a prospective series of 500 patients operated on by the shaving technique for deep rectovaginal endometriotic nodules. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 25, 1949–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malzoni, M.; Di Giovanni, A.; Exacoustos, C.; Lannino, G.; Capece, R.; Perone, C.; Rasile, M.; Iuzzolino, D.; Information, P.E.K.F.C. Feasibility and Safety of Laparoscopic-Assisted Bowel Segmental Resection for Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study with Description of Technique. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2016, 23, 512–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, K.; Nakaoka, H.; Yoshihara, K.; Ishiguro, T.; Tamura, R.; Mori, Y.; Yamawaki, K.; Adachi, S.; Takahashi, T.; Kase, H.; et al. Clonal Expansion and Diversification of Cancer-Associated Mutations in Endometriosis and Normal Endometrium. Cell Rep. 2018, 24, 1777–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyendecker, G.; Wildt, L.; Mall, G. The pathophysiology of endometriosis and adenomyosis: Tissue injury and repair. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2009, 280, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, V.J.; Ahmad, S.; Duncan, W.C.; Horne, A.W. The role of TGF-β in the pathophysiology of peritoneal endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2017, 23, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman, H.; Tuech, J.-J. New disc excision procedure for low and mid rectal endometriosis nodules using combined transanal and laparoscopic approach. Color. Dis. 2014, 16, O253–O256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman, H. Rectal shaving using PlasmaJet in deep endometriosis of the rectum. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 100, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman, H. Disc Excision using Transanal Circular Stapler for Deep Endometriosis of the Rectum in 10 Steps. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2021, 28, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, H.; Darwish, B.; Bridoux, V.; Chati, R.; Kermiche, S.; Coget, J.; Huet, E.; Tuech, J.-J. Functional outcomes after disc excision in deep endometriosis of the rectum using transanal staplers: A series of 111 consecutive patients. Fertil. Steril. 2017, 107, 977–986.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, H.; Ness, J.; Suciu, N.; Bridoux, V.; Gourcerol, G.; Leroi, A.M.; Tuech, J.J.; Ducrotté, P.; Savoye-Collet, C.; Savoye, G. Are digestive symptoms in women presenting with pelvic endometriosis specific to lesion localizations? A preliminary prospective study. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 3440–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballard, K.; Lane, H.; Hudelist, G.; Banerjee, S.; Wright, J. Can specific pain symptoms help in the diagnosis of endometriosis? A cohort study of women with chronic pelvic pain. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 94, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nnoaham, K.E.; Hummelshoj, L.; Kennedy, S.H.; Jenkinson, C.; Zondervan, K.T. Developing symptom-based predictive models of endometriosis as a clinical screening tool: Results from a multicenter study. Fertil. Steril. 2012, 98, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surrey, E.; Carter, C.M.; Soliman, A.M.; Khan, S.; DiBenedetti, D.B.; Snabes, M.C. Patient-completed or symptom-based screening tools for endometriosis: A scoping review. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2017, 296, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dariane, C.; Moszkowicz, D.; Peschaud, F. Concepts of the rectovaginal septum: Implications for function and surgery. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2015, 27, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klapczynski, C.; Derbal, S.; Braund, S.; Coget, J.; Forestier, D.; Seyer-Hansen, M.; Tuech, J.; Roman, H. Evaluation of functional outcomes after disc excision of deep endometriosis involving low and mid rectum using standardized questionnaires: A series of 80 patients. Color. Dis. 2020, 23, 944–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman, H.; Vassilieff, M.; Gourcerol, G.; Savoye, G.; Leroi, A.M.; Marpeau, L.; Michot, F.; Tuech, J.-J. Surgical management of deep infiltrating endometriosis of the rectum: Pleading for a symptom-guided approach. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 26, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angioni, S.; Mais, V.; Contu, R.; Milano, F.; Peiretti, M.; Santeufemia, S.; Melis, G.B. Pain control and quality of life after laparoscopic in-block resection of deep infiltrating endometriosis versus incomplete surgical treatment with or without medical therapy. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2006, 13, S66–S667. [Google Scholar]

- Ceccaroni, M.; Clarizia, R.; Bruni, F.; D’Urso, E.; Gagliardi, M.L.; Roviglione, G.; Minelli, L.; Ruffo, G. Nerve-sparing laparoscopic eradication of deep endometriosis with segmental rectal and parametrial resection: The Negrar method. A single-center, prospective, clinical trial. Surg. Endosc. 2012, 26, 2029–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, H.; Bubenheim, M.; Huet, E.; Bridoux, V.; Zacharopoulou, C.; Daraï, E.; Collinet, P.; Tuech, J.-J. Conservative surgery versus colorectal resection in deep endometriosis infiltrating the rectum: A randomized trial. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabrouk, M.; Ferrini, G.; Montanari, G.; Di Donato, N.; Raimondo, D.; Stanghellini, V.; Corinaldesi, R.; Seracchioli, R. Does colorectal endometriosis alter intestinal functions? A prospective manometric and questionnaire-based study. Fertil. Steril. 2012, 97, 652–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman, H.; Bridoux, V.; Merlot, B.; Resch, B.; Chati, R.; Coget, J.; Forestier, D.; Tuech, J.-J. Risk of bowel fistula following surgical management of deep endometriosis of the rectosigmoid: A series of 1102 cases. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 35, 1601–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braund, S.; Hennetier, C.; Klapczynski, C.; Scattarelli, A.; Coget, J.; Bridoux, V.; Tuech, J.J.; Roman, H. Risk of Postoperative Stenosis after Segmental Resection versus Disk Excision for Deep Endometriosis Infiltrating the Rectosigmoid: A Retrospective Study. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2021, 28, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloyiannis, I.; Perivoliotis, K.; Diamantis, A.; Tzovaras, G. Virtual ileostomy in elective colorectal surgery: A systematic review of the literature. Tech. Coloproctol. 2019, 24, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokor, A.; Hudelist, G.; Dobó, N.; Dauser, B.; Farella, M.; Brubel, R.; Tuech, J.; Roman, H. Low anterior resection syndrome following different surgical approaches for low rectal endometriosis: A retrospective multicenter study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meuleman, C.; Tomassetti, C.; D’Hoore, A.; Van Cleynenbreugel, B.; Penninckx, F.; Vergote, I.; D’Hooghe, T. Surgical treatment of deeply infiltrating endometriosis with colorectal involvement. Hum. Reprod. Update 2011, 17, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darai, E.; Ackerman, G.; Bazot, M.; Rouzier, R.; Dubernard, G. Laparoscopic segmental colorectal resection for endometriosis: Limits and complications. Surg. Endosc. 2007, 21, 1572–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracale, U.; Azioni, G.; Rosati, M.; Barone, M.; Pignata, G. Deep pelvic endometriosis (Adamyan IV stage): Multidisciplinary laparoscopic treatments. Acta Chir. Iugosl. 2009, 56, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, S.; Anserini, P.; Abbamonte, L.H.; Ragni, N.; Camerini, G.; Remorgida, V. Fertility after bowel resection for endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 92, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mereu, L.; Ruffo, G.; Landi, S.; Barbieri, F.; Zaccoletti, R.; Fiaccavento, A.; Stepniewska, A.; Pontrelli, G.; Minelli, L. Laparoscopic treatment of deep endometriosis with segmental colorectal resection: Short-term morbidity. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2007, 14, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, H.; Abo, C.; Huet, E.; Bridoux, V.; Auber, M.; Oden, S.; Marpeau, L.; Tuech, J.-J. Full-Thickness Disc Excision in Deep Endometriotic Nodules of the Rectum. Dis. Colon Rectum 2015, 58, 957–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Avout-Fourdinier, P.; Lempicka, M.; Gilibert, A.; Savoye-Collet, C.; Marpeau, L.; Hennetier, C.; Tuech, J.-J.; Roman, H. Posterior rectal pouch after large full-thickness disc excision of deep endometriosis infiltrating the low/mid rectum and relationship with digestive functional outcome. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 49, 101792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iversen, M.L.; Seyer-Hansen, M.; Forman, A. Does surgery for deep infiltrating bowel endometriosis improve fertility? A systematic review. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2017, 96, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.; Thomin, A.; Mathieu D’Argent, E.; Lass, E.; Canlorbe, G.; Zilberman, S.; Belghiti, J.; Thomassin-Naggara, I.; Bazot, M.; Ballester, M.; et al. Fertility before and after surgery for deep infiltrating endometriosis with and without bowel involvement: A literature review. Minerva Ginecol. 2014, 66, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bendifallah, S.; Roman, H.; D’Argent, E.M.; Touleimat, S.; Cohen, J.; Darai, E.; Ballester, M. Colorectal endometriosis-associated infertility: Should surgery precede ART? Fertil. Steril. 2017, 108, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nastasia, Ş.; Simionescu, A.A.; Tuech, J.J.; Roman, H. Recommendations for a Combined Laparoscopic and Transanal Approach in Treating Deep Endometriosis of the Lower Rectum—The Rouen Technique. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11050408

Nastasia Ş, Simionescu AA, Tuech JJ, Roman H. Recommendations for a Combined Laparoscopic and Transanal Approach in Treating Deep Endometriosis of the Lower Rectum—The Rouen Technique. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2021; 11(5):408. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11050408

Chicago/Turabian StyleNastasia, Şerban, Anca Angela Simionescu, Jean Jacques Tuech, and Horace Roman. 2021. "Recommendations for a Combined Laparoscopic and Transanal Approach in Treating Deep Endometriosis of the Lower Rectum—The Rouen Technique" Journal of Personalized Medicine 11, no. 5: 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11050408

APA StyleNastasia, Ş., Simionescu, A. A., Tuech, J. J., & Roman, H. (2021). Recommendations for a Combined Laparoscopic and Transanal Approach in Treating Deep Endometriosis of the Lower Rectum—The Rouen Technique. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 11(5), 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11050408