Depressive Symptoms in Expecting Fathers: Is Paternal Perinatal Depression a Valid Concept? A Systematic Review of Evidence

Abstract

:1. Introduction

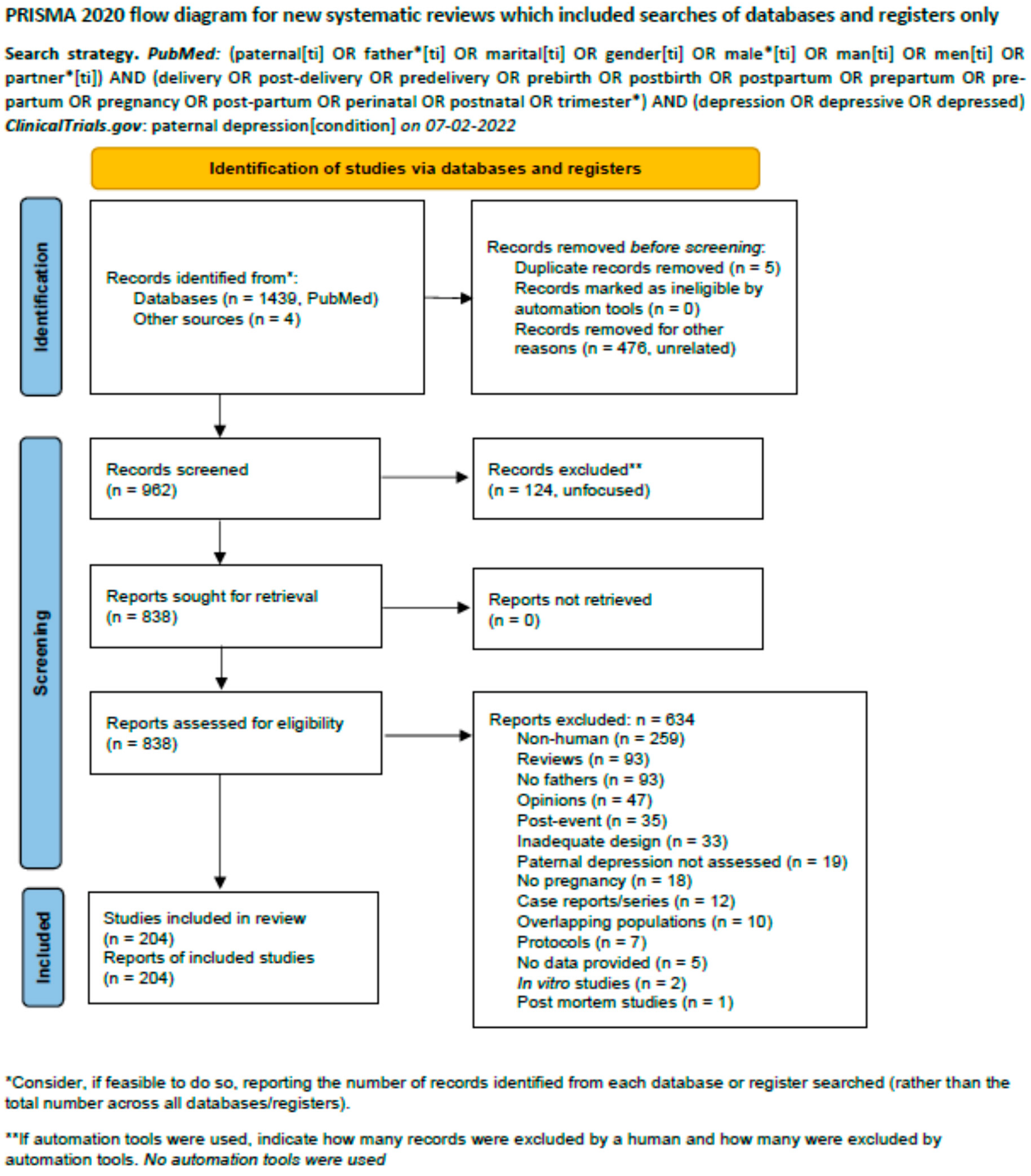

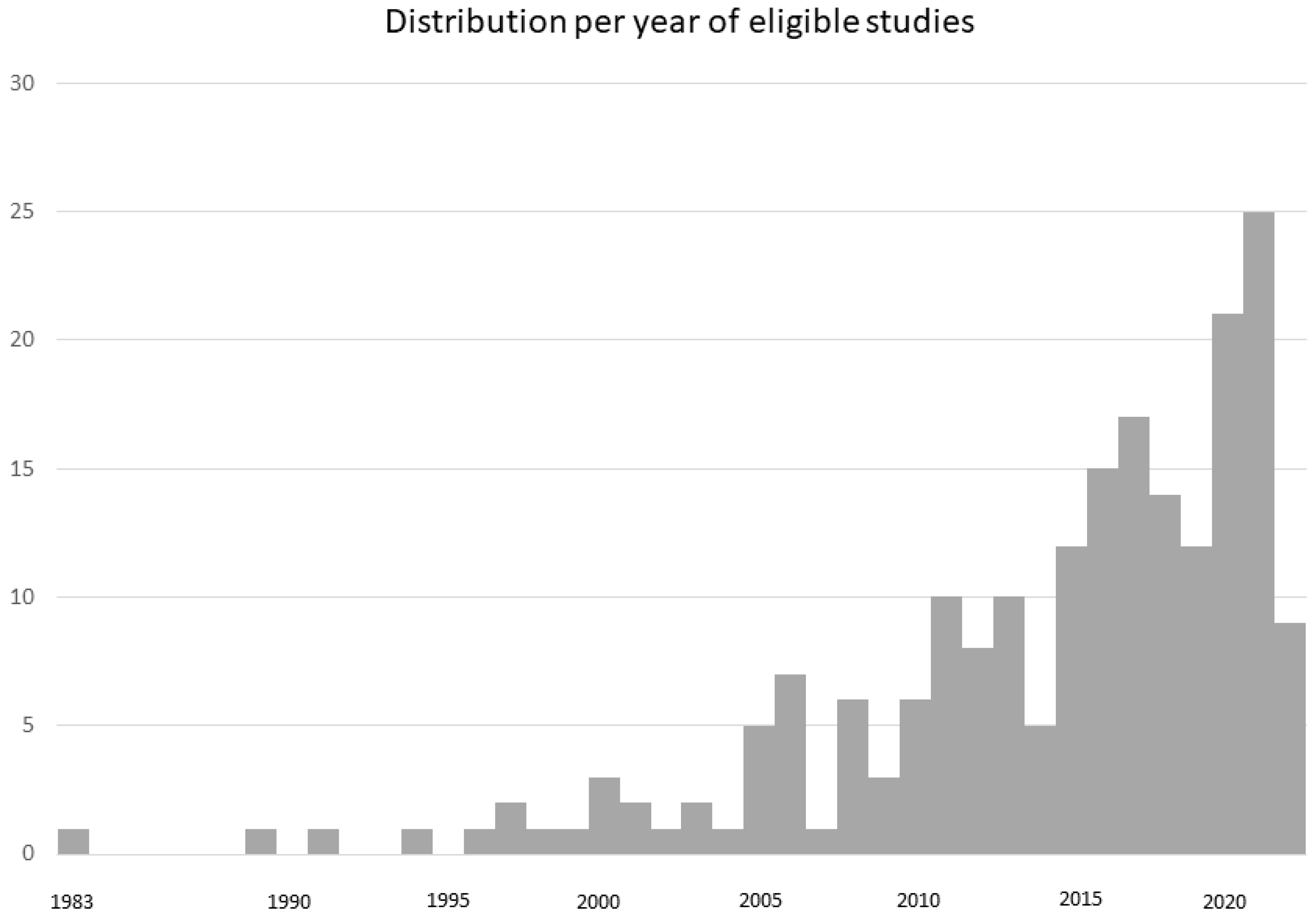

2. Methods

3. Results

| Study | Population Studied | Design/Instruments | Results | Conclusions/Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [12] | 50 first-time fathers, age, , mean 27.1 yr, range 18–45 | Cross-sectional. Prenatal questionnaire: SMAT, DI, BCAI, FAIOF, FAIOC. Postnatal: DI, BCAI LCI. Subjects completed questionnaires within 3 wks of their infant’s birth and again 3–5 wks postpartum | 3 items on the DI, both prenatally and postnatally, reflecting some degree of disturbance of the fathers were irritability, sleep disturbance, and fatigability. The SMAT resulted in a total sample mean of 124.6, which indicated that the sample was maritally well-adjusted. Prenatal BCAI was 2.57 out of 3.0 compared to 2.1 on the postnatal BCAI. The results of the FAIOF showed subjects reporting a mean of 10.8. In contrast, prospective fathers reported on the FAIOC that they planned to be involved in 12.7 out of 13 of the activities with their infant. In LCI new fathers reported lifestyle changes in an average of 38% of the lifestyle items. Thirty-seven subjects reported not having a sex preference for the expected infant. Of the 16 who did have a preference, 12 preferred a boy and four preferred a girl. Prior to the infant’s birth, 36 husbands reported they were equal in importance to the mother, 16 felt less important, and one felt more important. Postnatally, 29 fathers felt equal to the mother, 19 felt less important, and two fathers felt more important in the care of their baby. For 44/53 fathers to be, pregnancies were planned. Expectant fathers reported in the last three weeks of their wife’s pregnancy that the method of infant feeding would be totally breastfed (37), partially breastfed (11), and formula fed (5). 3–5 wks after baby’s birth, fathers reported that 21 infants were totally breastfed, 10 were partially breastfed, and 19 were formula fed | Very few symptoms of depression were noted in the sample, so the correlations between variables, though statistically significant, require further investigation. Greater age, higher income, more years of education, and good marital adjustment were associated with fewer signs of depression. Fathers who reported more lifestyle changes and greater involvement in baby care also reported more signs of depression especially irritability, sleep disturbance, and fatigability. Age and months married did seem to have an impact on the marital adjustment of the couples. Older fathers seemed to project fewer baby care activities while younger fathers planned to do everything. No significant relationship between The FAIOF and the prenatal or postnatal BCAI suggests that many other factors impact collectively to predict the father’s involvement. Unplanned pregnancies (17%) related to greater lifestyle changes |

| [13] | T0 (Pregnancy) = 147 fathers; T1 (Early post-partum) = 117 fathers; T2 (1 mo.) = 106 fathers; T3 (4 mo.) = 85 fathers; T4 (8 mo.) = 82 fathers; 2/3 of sample Anglo-White, 10% Asian, 14% Hispanic, 3% Black, and 6% other. Age = 31.30 | Cross-sectional. GHI, HPQ, STAI, CES-D, SOMS, PSOC, FFFS, MAT, ISSB and questionnaire for perceived support, RSE, LES and a questionnaire for mate’s pregnancy risks | Physical symptoms: no linear increase over time. Psychological Symptoms: At T4 anxiety scores increase, although not significantly. Depression results 8.94, ±7.96; 9.07,± 7.62; 9.21,± 7.18; 8.98, ±7.41; 9.47, ±1.36. General health status indicated a decrease over time | At T4 psychological symptoms of anxiety and depression did not change significantly. At T0, 52% of the variance in depression was explained. A T1, 42%, and T2, 45% of the variance in anxiety was explained. At T3, 43%, and T5, 50% of the variance in depression was explained. A consistent predictor of anxiety and depression was parental competence |

| [14] | T0 (5 wks pre delivery) = 192 individuals; T1 (8 wks post-delivery) = 177 individuals | Cross-sectional. SSNI, CES-D. | Woman have significantly higher levels of depressive symptomatology at T0. Over time woman’s levels of depression decrease at the trend level, whereas men’s levels increased slightly. Women also scored higher than men on perceived practical and emotional support and reassurance at each timepoint. Overall, social support did not correlate with depressive symptomatology for either gender at T0, whereas overall support was inversely correlated with ♀ symptoms at T1 but not with ♂ symptoms at T1. Each dimension of support was inversely correlated to depressive symptoms in ♀ at T1, whereas only practical support and reassurance were linked to T1 depressive symptomatology in ♂. | ♀ and ♂ did not differ in depressive symptoms at T1. The characterization of depressive mood in the postpartum period as a predominantly “female problem” may constitute a social construction of reality inadequately subjected to empirical testing by means of gender comparison |

| [15] | 200 postnatal couples Mothers, Age = 28.8 yr. Fathers, Age = 27.7 yr vs. 155 control couples | Longitudinal. EPDS 13-item version; T0 (6 wks postpartum) T1 (6 mo. postpartum) | Prevalence of depression: 27.5% in mothers at T0 25.7% in mothers at T1 9.0% in fathers at T0 5.4% in fathers at T1 39 of all participants who scored 13 or more on the EPDS at six months postpartum, and their partners agreed on PAS interview. Comparing the results, the sensitivity of the EPDS, using a cut-off score of 13, was 95.7% for cases of depression in mother and 85.7% in fathers. Specificity, 71% for mothers and 75% in fathers. | The prevalence did not differ significantly in either mothers or fathers from a control group. As expected, mothers had a significantly higher prevalence of psychiatric “caseness” both T0 and T1 than fathers. Fathers were significantly more likely to be cases if their partners were also cases |

| [16] | 54 first-time mothers and 42 of their husbands from Oporto (Portugal) ♀ = 25 yr range 17–38 ♂ = 26.2 yr range 20–37 | Longitudinal. EPDS and SADS at T0 = 6 mo. antenatally. T1 = 3 mo. postnatally (subsample:24 ♀ 12 ♂) T2 = 12 mo. Postnatally | Prior pregnancy: 46.3% ♀ had at least one episode of depression. 21.4% ♂ ♀ had a significantly greater lifetime history of depression than did the ♂. during pregnancy: the difference was not statistically significant 16.7%♀ 4.8% ♂ after childbirth: 49.0% ♀ 23.8% ♂ Comparing the ♀ to the ♂ cumulative incidence of depression at the periods 0–3 and 4–12 months after birth, a statistically significant difference was found in the first period, but not in the last | Giving birth and being more directly involved in child rearing renders mothers more vulnerable than fathers to depression in the first few months postnatally. postnatal depression in the fathers seems to follow on from the early occurrence of depression in their wives |

| [17] | 55 married couples. yr range 18–45; expected first child. 97% White, 4.5% Hispanic, 2.7% Asian. ♀ = 30 yr ± 4.6 ♂ = 32 yr ± 4.7 | Longitudinal. T0 = ♀ second trimester T1 = 6 mo. Post-delivery. Questionnaire for the perception of work, SSNI, CES-D | CES-D score for ♀ at T0 was 14.9 and 13.6 at T1; for ♂ at T0 was 10.08 and 10 at T1. At T0 and T1 ♀ scores were significantly higher than ♂. At T1 31% of ♀ and 18% of ♂ scores 16 or higher indicating probable depressive symptomatology | When ♂ and ♀ were analyzed together, perceptions of low levels of emotional support from partner and low control and social gratification at work and in the parenting, role were significant predictors of higher depressive symptomatology. Perception of boss supportiveness and social gratification at work were more important for ♀ who were working than for ♂ |

| [18] | 370 Irish mothers and their partners. T0 = 289 ♀, 181 ♂ T1 = 224 ♀, 175 ♂ | Longitudinal. EPDS, Highs Scale. T0 = 3 d postpartum T1 = 6 wks postpartum | At T0, 11.4% of ♀ scores ≥ 13 on EPDS = 6.8 ± 4.8 and 18.3% scores ≥ 8 on Highs Scale = 4.4 ± 3.1 3% of ♂ scores ≥ 13 on EPDS = 4.1 ± 3.2 at T1 11% of ♀ scores ≥ 13 on EPDS = 6.9 ± 4.7 and 9% scores ≥ 8 on Highs Scale = 3.3 ± 2.8. 1.2% of ♂ scores ≥ 13 on EPDS = 3.1 ± 2.9 and 11% scores ≥ 8 on Highs Scale = 4 ± 3.4 | Mothers’ mood state at 3 days postpartum was the best predictor of psychopathology at 6 weeks suggesting that it is possible to identify mothers at risk of postnatal mood disturbance. Mood disturbance in partners was not prominent and when present, it was elation rather than depression, possibly consistent with the effect of a supposed positive life event such as childbirth. Only two partners displayed symptoms of depression 6 weeks postnatally, suggesting that the mood disturbance experienced by mothers after childbirth may be more related to the biological and hormonal aspects of the event rather than the life event |

| [19] | Longitudinal study. 7018 English partners of female participants. 6667 completed all the tests | Longitudinal. EPDS, a questionnaire investigating family structure, an inventory for stressful life events, a questionnaire for social support, a questionnaire for quality of partnership and a relationships history. T0 = 18 wks of gestation T1 = 8 wks posr birth | At T0 3.5% of ♂ scores ≥ 12 at EPDS = 4.06 ± 3.80. at T1 3.3% of ♂ scores ≥ 12 at EPDS = 3.70 ± 3.76 | These rates varied significantly by family type: men in stepfamilies had more than twice the rates found for men in traditional families before the birth and after the birth. Men’s depressive symptoms were correlated with their partners’ depressive symptoms before and following delivery. The correlations between mothers’ and partners’ depressive symptoms in the stepfather families before the birth and after the birth were higher than for the men in other family types before the birth and following the birth. |

| [20] | 51 couples, 26 expecting the first child, 25 the second. ♂ = 32.79 yr ± 5.52 ♀ = 30.43 yr ± 4.57 | Longitudinal. CES-D, PANAS, DAS-S, PSI-SF, COPE T0 = recruitment T1 = 2 wks postpartum | For ♂ only statistically significant correlation was between number of children and coping. For ♀ was between number of children and parenting stress. At T1 ♀PA and NA were significantly correlated. ♂PA and NA were significantly correlated as were PA and depression and depression and NA. At T1 39.2% of ♀ were depressed. 35% mild depression, 50% moderate depression, 15% severe depression. for ♂ 25.5% were depressed. 69.2% mild depression, 30.8% moderately depressed and none severely depressed. | A notable proportion (25–39%) of parents in this study reported elevated depressive symptoms. In nearly half couples (47%) at least one parent reported elevated depressive symptoms, and in nearly 20% both parents did so. |

| [21] | Longitudinal study. 124 couples with unintended first pregnancy. 58.90/, white, 25% African American, 7.7% Hispanic, and 7.7% Asian ♂ = 31.5 yr ± 5 ♀ = 30 yr ± 4.1 34% lived in Chicago and 66% in surrounding suburbs. All the couples were living together, and 94.8% were married. | Longitudinal. A questionnaire to investigate pregnancy intent, CES-D, a questionnaire to investigate relationship distress and a questionnaire for social support. T0 = 2–3 mo. antenatal T1 = 4 mo. postpartum | In this sample, pregnancy had been unintentional for 33.9% of ♂ and 29% of ♀. ♀ CES-D T0 = 12.37 ± 9.53 T1 = 6.94 ± 6.22 ♂ CES-D T0 = 6.12 ± 6.43 T1 = 5.21 ± 5.95 | A strong association between men’s perception that a pregnancy was unintended and maternal depressive symptomatology was detected. Women’s reports of unintended pregnancy showed a tendency for decreased postpartum depressive symptoms. The findings for men were at the trend level. |

| [22] | 327 couples with a first-time pregnancy, from Melbourne T0 = 251 T1 = 204 T2 = 166 T3 = 151 ♂ = 32 yr ♀ = 30 yr | Longitudinal. EPDS, PANAS, DI-SF, State anger and anxiety scale, DAS, intimate bond questionnaire, SSQ, the masculine and feminine gender role stress scale. T0 = 24–26 wks antenatally T1 = 36 wks antenatally T2 = 1 wk postnatally T3 = 4 mo. postnatally | Scores ≥ 10 at EPDS for ♂ are: T0 = 12% T1 = 8.7% T2 = 6% T3 = 5.8 For ♀: T0 = 19.5% T1 = 21.1% T2 = 21.6% T3 = 13.9% | The incidence of distress/dysphoria in women and men during mid-and late pregnancy is of concern. The patterns of incidence and onset of distress differed between ♀ and ♂. This difference is characterized by a gradual increase in distress in vulnerable ♀ from mid-pregnancy until after the arrival of the baby, while ♂ who report distress in mid pregnancy appear gradually to resolve this over time leaving a smaller residual group of troubled ♂ by the time the pregnancy is over |

| [23] | Longitudinal study. 157 first time couples | Longitudinal. SADS, DSQ, IBM, BDI, GHQ, EPDS, PBI, IPSM. T0 = 20–24 wks antenatally T1 = 6 wks postnatally T2 = 12 wks postnatally T3 = 52 wks postnatally | Cumulative incidence of depression by 12 mo. postpartum ♂ = 10.1%, ♀ = 27.3%. Using the BDI cut off > 16: ♀: T0 = 0%; T1 = 7.7%; T2 = 3.7%; T3 = 4.4% ♂: T0 and T1 = 0.7%; T2 = 0.8%; T3 = 3.1%. On GHQ ♀ scores higher than ♂ antenatally and postnatally but not at T3. For ♀ and ♂ there was a positive significant correlation between their level of neuroticism and their depression scores at each of the four assessment points | The prevalence of depression was measured by calculating the percentage of ♂and ♀ who scored above the EPDS (♀, 6 wks postpartum), the BDI, or the GHQ (♀and ♂, remaining timepoints) clinical cut-off points each assessment period. The incidence of self-reported depression in ♂ was consistently lower than in ♀ Theories for this gender difference include an under-reporting of depressed affect by men, either due to a real difference in the experience of depression poorer recall of symptoms by men expressing disturbed affect through different symptoms than those assessed on diagnostic interviews or self-report measures |

| [24] | 251 couples from Sydney. the sample sizes for the data analyses vary from 200 to 218 for the ♂, 230 to 238 for the ♀, and 212 to 218 for couples. Numbers vary depending upon whether the analyses inspect complete self-report data, caseness data, or a combination of both. ♂ = 29.1 yr ± 4.6 ♀ = 27.2 yr ± 4.2 | Cross-sectional. EPDS, CES-D, DIS 6–7 wks postpartum. | 11 ♂ met criteria for distress, 3 for depression only, 3 for comorbid depression and anxiety, 5 for anxiety disorder. Of the 208 ♂ providing data for both depression and anxiety modules of the DIS, 2.9% met criteria for depression and 5.3% for distress caseness. 16 ♀ met criteria for depression only, 6 for panic, and 5 for anxiety. Of the 230 ♀, 10.4% met criteria for depression and 16.1% for distress. EPDS scores: Distressed ♂ = 9.4 ± 5; Non-distressed ♂ = 4.1 ± 3.5. ♂ and ♀ differed significantly on scores (♂ = 4.35 ± 3.72 vs. ♀ = 6.34 ± 4.33; p < 0.01) | The EPDS is both reliable and valid for fathers. It discriminates between distressed and non-distressed fathers, using caseness of either just depression or depression and anxiety. Rate of depression in ♂ may at first seem low. However, when compared to large scale community studies it appears to agree with the general finding of lower rates of depression in husbands than wives |

| [25] | A 6-mo follow- up of a community sample of women who were evaluated for psychiatric disorders at 2 mo postpartum. 48 couples and 50 controls. Couple age: ♂ = 32.0 yr ♀ = 29.9 yr Control age: ♂ = 33.8 yr ♀ = 30.3 yr | Cross-sectional. EPDS, SCID-NP, LIFE, SCL-90-R, a life stress scale of the parenting stress index and a questionnaire for treatment history. | In the original sample, 17 ♂ (24%) were diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder at 2 mo postpartum. 2 of these ♂were lost to follow-up. Of the 15 ♂, 9 (60%) remained symptomatic at 6 mo postpartum. 3 new cases were diagnosed at 6 mo. Anxiety and depression scores were elevated among ♂in the index group, whether or not the ♀were in remission at 6 months. Life stress was found to be correlated with ♀depressive symptoms on the SCL90-R, with ♂ depressive symptoms, and with ♂somatic symptoms. | The results of this study of a community sample of postpartum women and their partners indicates that mental health problems tended to persist for several mo. after the birth of the infant. The results of this study confirm other research showing that the partners of women with postpartum psychiatric disorders often exhibit mental health problems. Many of the fathers appeared to be suffering from chronic mental health problems, which continued to affect them after the birth of their children. However, even among fathers with no psychiatric diagnosis, those whose partners had a postpartum psychiatric disorder continued to report relatively high levels of psychological symptoms at 6 mo. postpartum |

| [26] | Longitudinal study 127♀ and 122♂ ♂ = 31.2 yr (range 17–49) ♀ = 28.2 yr (range 18–39) | Longitudinal. GHQ-28, STAI, IES. T0 = 0–4 d after birth T1 = 6 wks postpartum T2 = 6 mo postpartum | Depression: T0♂ = 0.101 T0♀ = 0.137 T1♂ = 0.137 T1♀ = 0.055 T2♂ = 0.079 T2♀ = 0.108 Psychological distress: T0♂ = 16.4 T0♀ = 22.0 T1♂ = 17.9 T1♀ = 17.2 T2♂ = 15.9 T2♀ = 16.7 State Anxiety: T0♂ = 29.5 T0♀ = 30.5 T1♂ = 30.2 T1♀ = 29.2 T2♂ = 15.9 T2♀ = 30.1 | The present study clearly demonstrates that within a six-month perspective, the birth of a healthy child only provokes long term psychological distress in 19% of mothers and 11% of fathers |

| [27] | 2 samples of first-time parents from Sydney. First sample: 216 ♀ 196 ♂ ♂ = 29.1 yr ± 4.6 (range 20–44) ♀ = 27.2 yr ± 4.2 (18–41) Second sample: 192 ♀ 160 ♂ ♂ = 29.4 yr ± 4.7 (range 20–47) ♀ = 27.5 yr ± 3.5 (19–38) | EPDS, CES-D, POMS 6–8 wks postpartum. At the 6-week home interview the mother and father were separately administered the Diagnostic Interview Schedule: Depression and Anxiety modules | ♀ meeting criteria for both depression and anxiety at 6 wks postpartum had a significantly higher antenatal EPDS score ( 11.7 ± 5.8) than those with just anxiety ( 8.3 ± 4.4) depression ( 7.0 ± 3.2). ♂ with just depression scored significantly higher on their antenatal CES-D ( 16.5 ± 18.2) than those with either no disorder postpartum ( 7.4 ± 6.2) or a mix of anxiety and depression ( 6.0 ± 6.8) | Do not appear to be a clear pathway for the differential development of an anxiety or depressive disorder postpartum for ♀. A history of an anxiety disorder appears to be a greater risk factor for the development of postpartum mood disorder than a history of a depressive disorder. No Such finding was evident for the development of disorders in ♂ |

| [28] | 472 pregnant ♀and 308 expectant fathers ♂ from Lübeck, Germany, divided in 3 groups: Group 1: 88 ♀ 61 ♂ Group 2: 344 ♀ 223 ♂ Group 3: 40 ♀ 24 ♂ | Cross-sectional. ADS-L for depressive reaction. Short questionnaire of actual stress by Müller and Basler for perceived stress. | ADS-L scores: Group 1: Normal: 90% ♀ 98% ♂ Depressive: 9.5% ♀ 2% ♂ Group 2: Normal: 90% ♀ 97.5% ♂ Depressive: 10% ♀ 2.5% ♂ Group 3: Normal: 94% ♀ 96% ♂ Depressive: 6% ♀ 4% ♂ Stress reaction before prenatal testing Group 1: ♀ = 3.4 ± 0.9 ♂ = 3.1 ± 0.8 Group 2: ♀ = 3.4 ± 1.5 ♂ = 3.1 ± 0.8 Group 3: ♀ = 3.9 ± 1.3 ♂ = 3.6 ± 0.5 Stress reaction after prenatal testing: Group 1: ♀ = 3.1 ± 1.4 ♂ = 2.9 ± 1.0 Group 2: ♀ = 2.5 ± 1.3 ♂ = 2.6 ± 1.0 Group 3: ♀ = 3.3 ± 1.2 ♂ = 3.1 ± 0.5 | ADS scores ≤ 23 normal ≥23 depressive. Questionnaire for stress total scores range from 1 (minimum stress) to 6 (maximal stress). Comparable analysis of depressive reactions before prenatal diagnosis showed no significant difference between the prenatal test groups neither for the pregnant women nor for their partners |

| [29] | 284 ♂. 216 ♂ their partner having had a ‘normal’ unassisted delivery and 68 ♂ their partner miscarried < 24th week of gestation = 32.1 yr ± 7.3 (18–56) | Longitudinal. IES, BDI, STAI-state, CRI. T0 = pregnancy (beginning of second trimester) T1 = Birth/Miscarriage T2 = 1 yr after birth/miscarriage | BDI scores: T0 = 5.15 ± 2.42 T1 = 8.61 ± 4.44 T2 = 5.76 ± 3.11 STAI-Y1 scores: T0 = 37.91 ± 9.06 T1 = 38.73 ± 9.96 T2 = 34.51 ± 9.47 | Simple effects revealed that between T0 and T1 there was a significant increase on all of the outcome measures with the exception of anxiety, and a change in the coping repertoire used. Between T0 and T2, there was a significant reduction in all outcome measures. In the present sample of men, pregnancy was associated with high levels of stress and anxiety, above that which would be expected for a non-psychiatric population. At pregnancy outcome, levels of stress, anxiety, and depression all increased irrespective of whether the outcome was a live birth or miscarriage. One year following outcome, anxiety and stress levels had fallen significantly below pregnancy levels, whereas depression levels, whilst showing a decrease compared to at the time of pregnancy outcome, remained significantly high compared to pregnancy |

| [30] | 48 ♂. 28 face to face survey 20 postal survey | Cross-sectional. HADS, EPDS, Brief PHQ. Brief PHQ cut-off > 10 EPDS cut-off > 12 HADS cut-off ≥ 8 | HADS: 8% ♂ mild depressed mood. EPDS > 12: 8% ♂ 2/4 ♂ > cut-off both HADS and EPDS | The prevalence of depressed paternal mood in the postnatal period was notable at 8%, however, depressed men did not participate in the follow-up study. There was a strong association between higher paternal depressed mood and fussier/more difficult infant temperament. |

| [31] | 106 couples ♀ = 32.13 yr ± 4.39 (22–44) ♂ = 34.18 yr ± 5.5 (24–52) 52% primiparous | Longitudinal. Blues questionnaire, EPDS (cut-off 9/10), PBQ, ICQT1 1 wk postpartumT2 2 mo postpartum | Blues questionnaire ♀ = 29.77 ± 16.57 ♂ = 18.32 ± 10.11 EPDS scores T1♀ = 6.09 ± 5.05 ♂ = 4.28 ± 2.64 T2♀ = 4.38 ± 3.79 ♂ = 2.5 ± 2.37 | The mean EPDS score was significantly higher in mothers than in fathers both at one week and at two months. New mothers experienced more blues symptoms, had higher overall mean percentage scores on the Blues Questionnaire than new fathers. The mothers’ mean percentage score of blues for each day peaked on day4 after the delivery, while fathers’ peaks on day 1 |

| [32] | Cross-sectional study at 22 wks ♀ gestation 50 teenage couples 50 non-teenage couple (control group) Teenage ♂ = 20.7 yr Non-teenage ♂ = 29.6 yr | Cross-sectional. HADS (HADS-A/HADS-D), GHQ-28 | Teenage ♂ scores: HADS median: 11.5 HADS-A median: 7.5 HADS-D median: 4 GHD-28 median: 9 Non-teenage ♂ scores: HADS median: 3 HADS-A median: 4 HADS-D median: 1 GHD-28 median: 0 | The younger age of onset of fatherhood was independently associated with higher HADS and GHQ-28 scores in a multivariate analysis. Symptoms in anxiety domains had a stronger association compared to those in depressive domains in both the HADS and GHQ-28 |

| [33] | 367 couples with an ART pregnancy. ♀ = 33.2 yr ± 4.4 ♂ = 35.2 yr ± 5.8; 379 spontaneous pregnancy couples (control). ♀ = 33.3 yr ± 3.0 ♂ = 34.1 yr ± 5.4; T0 = 18–20 wks of gestation T1 = 2 mo post-partum T2 = 12 mo post-partum | Cross-sectional. GHQ-36, STAI, checklist of nine changes and stressors for stressful life events. | ♂in the control group reported higher levels of depressive symptoms than ♂ in the ART group. Among ART ♂in both groups, depressive symptoms ↑ after the baby was born. ♂’s anxiety symptoms first ↓from pregnancy to post-delivery, and then ↑ at T2 in both ART and control groups | ART is not a risk factor for the development of psychological symptoms in mothers and fathers to be |

| [34] | 11833 ♀ 8431 ♂ | Longitudinal. EPDS cut-off ≥ 12 8 wks post-partum. ♂ reassessed at 21 mo. post-partum. | EPDS score ≥ 12: 10% ♀ 4% ♂ | ♂ depression might have a direct effect on the way ♂ interact with their children, as has been reported for postnatal depression and other psychiatric conditions in ♀. |

| [35] | 156 ♀ and their partner at 20 wks antenatally. ♀ = 28.4 yr ♂ = 33.5 yr First assessed with CES-D and divided in 2 groups: 36% depressed ♀ 32% depressed ♂ | Cross-sectional. CES-D, STAI, STAXI, Daily Hassles Scale. | Depressed ♂ score: CES-D: = 8.52 ± 6.0 STAI: = 34.9 ± 7.7 STAXI: = 18.3 ± 5.9 Daily hassles scale: = 20.6 ± 5.2 Non depressed ♂ score: CES-D: = 21.4 ± 9.3 STAI: = 44.2 ± 8.7 STAXI: = 21.8 ± 3.6 Daily hassles scale: = 28.3 ± 6.5 | Depressed ♂ as compared to non-depressed ♂ experience depression and anxiety symptoms during pregnancy, not unlike the depression and anxiety symptoms reported for depressed ♀ versus non-depressed ♀ during pregnancy. The level of depression and anxiety symptoms are not significantly different for depressed ♀ and depressed ♂ during pregnancy. |

| [36] | 5089 couples | Cross-sectional. Short form of CES-D. Total score between 10 and 14 moderate depression and ≥15 severe depression. | 14% ♀ and 10% ♂ had moderate or severe depressive symptoms. CES-D score: ♀ = 4.58 ± 4.96 ♂ = 3.69 ± 4.67 | Postpartum depression in ♂ was strikingly high (10%) and more than twice as common than in the general adult male population in the US |

| [37] | 58 ♂ with partner with PPD (index group) ♂ = 34.1 yr ± 6.5 ♀ = 32.2 yr ± 5.2 116 ♂without partner with PPD (comparison group) ♂ = 34.3 yr ± 5.2 ♀ = 32.3 yr ± 4.5 | Cross-sectional. BDI-II cut-off > 13, BAI cut-off > 7, GHQ-28 cut-off > 5, SPHERE, AUDIT, AQ | Index group score: AQ = 58.9 ± 16.7 AUDIT = 6.5 ± 4.5 BAI = 3.8 ± 4.5 BDI-II = 8.0 ± 6.4 GHQ-28 = 4.1 ± 4.3 SPHERE = 5.1 ± 7.4 Comparison group: AQ = 52.2 ± 11.9 AUDIT = 5.9 ± 4.7 BAI = 2.5 ± 3.5 BDI-II = 4.8 ± 4.7 GHQ-28 = 2.4 ± 3.3 SPHERE = 1.9 ± 3.6 | Index group reported poorer psychological health than comparison group, on depression, nonspecific psychological impairment and aggression. |

| [38] | 386 couples. ♂ = 30.3 yr ± 8.8 | Cross-sectional. BDI (cut-off ≥ 10 presence of depression; ≥19 mild/severe depression) 12th weeks postpartum | BDI >9: ♀ 23.6%; ♂ 11.9% BDI >18: ♀ 7.8%; ♂ 4.1% | As severity of ♀ depression increases, prevalence of ♂PPD increase. On the contrary, we had no information on paternal depression before the delivery, and, therefore, we are not able to state that maternal depression caused paternal depression. |

| [39] | 13 partners of ♀ with PND; ♂ = 29.8 yr ± 5.4 | Cross-sectional. BDI-II, SSNI, DAS, PSI | ♂ scores: BDI-II = 14.76 ± 6.82; SSNI = 2.89 ± 0.92; DAS = 99.69 ± 16.25; PSI = 84.46 ± 15.57 | Partners of women with PND showed none-to-mild depression levels |

| [40] | 194 ♂ with different methods of recruitment.124 via general practice postal5 via general practice attenders18 via child health surveillance clinic attenders28 via postnatal ward face-to-face19 via postnatal ward postal | Cross-sectional. HADS cut off ≥ 8 (8–10 = mild, 11–14 = moderate and 15–21 = severe) | ♂ HADS scores >8: Depressive symptoms 12%; Anxiety symptoms 30% | 17 of 23 ♂ scoring above the cut-off for depressive symptoms also scored above the cut-off for anxiety symptoms. |

| [41] | 101 couples ♂ = 32 yr ± 5.0 ♀ = 30 yr ± 5.1 T0 1–2 d postpartumT1 2 wks postpartumT2 6 wks postpartum | Longitudinal. EPDS, EPDS-P, BDI, HDRS. ♂ EPDS-P at T1 and T2♀ EPDS, BDI T0, T1, T2 HDRS over the phone at T2 | T1 EPDS = 6.8 ± 4.9 EPDS-P = 8.2 ± 4.3 BDI = 9.2 ± 6.8T2 EPDS = 5.0 ± 4.8 EPDS-P = 7.4 ± 5.0 BDI = 6.4 ± 6.4 HDRS = 5.4 ± 6.0 | The EPDS-P was found to be moderately related to both a clinician rating of depression and the women’s self-reported depression ratings. As expected, due to reliability of self-report data, the EPDS showed a significantly stronger correlation with the BDI and the HDRS than did the EPDS-P. |

| [42] | 367 couples with IVF/ICSI379 controls with spontaneous pregnancyT1 18–20 wks of gestation T2 2 mo postpartumT3 12 mo postpartum | Longitudinal. DAS at T2 and T3, BDI 13 item version at T1, Stressful Life Events questionnaire | Stressful life events ART group: ♂ 24.5% ♀ 23.4% Control group ♂ 29.0% ♀ 29.3% Depressive symptoms ART group None ♀ 18.3%, ♂ 35.7% Mild ♀ 31.2%, ♂ 28.0% Moderate ♀ 46.7%, ♂ 33.3% Severe ♀ 3.7%, ♂ 2.9% Control group None ♀ 18.4%, ♂ 33.5% Mild ♀ 36.9%, ♂ 31.8% Moderate ♀ 38.5%, ♂ 31.2% Severe ♀ 6.1%, ♂ 3.4% | Successful ART bears no risk for marital adjustment |

| [43] | 128 mother–father–infant triads | Cross-sectional. EPDS (cut-off: ≥10), PSI-SF, DAS, NCATS 2–3 wks postpartum | 28% ♀ and 13.3% ♂ had depression at 2–3 wks postpartum. EPDS, ♂ = 5.25; ♀ = 7.64 | Men whose partners had depression had significantly higher depression scores than did men whose partners had no depression. Maternal PPD affected study fathers in negative ways, as shown by higher levels of depression and parenting stress among men whose partners had depression. Paternal marital satisfaction was not associated with maternal depression at 2 to 3 months postpartum |

| [44] | 171 ♀ = 31.9 yr ± 4.7 133 ♂ = 33.8 yr ± 5.4 | Longitudinal. Blues Questionnaire, EPDS, VAS. VAS mood asked: happiness, depressed, tiredness, anxiety. EPDS cut-off ≥ 10. Assessments at 1 week postdelivery and 2 months postdelivery | 1 wk postpartum: Blues Questionnaire: ♂ = 18.61 ± 9.93 ♀ = 30.56 ± 16.05. VAS: Depressed: ♂ = 7.8 ± 10.75 ♀ = 19.01 ± 18.4 Happiness: ♂ = 84.35 ± 12.7 ♀ = 81.18 ± 14.6 Tiredness: ♂ = 52.06 ± 24.16 ♀ = 64.96 ± 24.16 Anxiety: ♂ = 26.01 ± 20.58 ♀ = 35.83 ± 25.11. EPDS: ♂ = 4.47 ± 2.76 ♀ = 6.52 ± 5.08. Only 1 scored above 10 (0.75%). At 2 mo. 12% of ♀ scores 10 or higher on EPDS = 4.76 ± 3.91 ♂ = 2.8 ± 2.44 significantly lower than the score at 1 wk | It was expected that ♀ showed more blues and depressive symptoms than ♂. This has also been found antenatally and in the first months postpartum. Two subscales of Blues Questionnaire’s ‘primary blues’ and ‘hypersensitivity’ was most predictive for high EPDS scores at 2 months in new ♂, while in ♀ the subscale ‘depression’ was most predicted for depressive symptoms later on. |

| [45] | Survey 687 ♀ (28/31 wks pregnant) 669 ♂ | Cross-sectional. EPDS (♀ cut off ≥ 12/13, ♂ cut-off > 11), Marital Satisfaction Scale, The Duke-UNC functional social support questionnaire. | Depressed ♀: 10.3% depressed ♂: 6.5%. Depression of ♂ when ♀ experience depression in pregnancy: 14.5% of ♀ when ♂ experience depression during their partner’s pregnancy: 23.3% | Low marital satisfaction increased the probability of depression during pregnancy in women and men. Among men low affective social support was associated with depression during pregnancy. The prevalence of depression during pregnancy was higher among ♀ and although most psychosocial and personal factors associated with depression during pregnancy were similar for both sexes, low affective social support and partner’s depression were only related to ♂ depression. |

| [46] | 9846 (76.4%) ♂ at T0 8332 (64.7%) ♂ at T1, 7090 (55.0%) ♂ at T2, 6101 (47.4%) ♂ at T3, 4792 (37.1%) ♂ from all four time points. Data with at least one time point: 10,975 ♂ T0: 18 wks prenatally; T1: 8 wks postnatally; T2: 8 mo. Postnatally; T3: 21 mo. postnatally | Longitudinal. EPDS cut off >12 | Depression score > 12 for sample with data at all four time point: T0: 2.88% (CI 2.41–3.35); T1: 2.55% (CI 2.10–3.00); T2: 2.32% (CI 1.89–2.75); T3: 3.05% (CI 2.56–3.54); Depression score >12 using imputed data for those with data on at least one time point: T0: 3.88% (CI 3.52–4.24); T1: 3.64% (CI 3.29–3.99); T2: 3.44% (CI 3.10–3.78); T3: 3.87% (CI 3.51–4.23) | Depression in men is relatively common. There is a suggestion from these findings that depressive symptoms are even more common in the prenatal period than postnatally, although the proportion of fathers with high scores changes little across this period. |

| [47] | 2 groups:53 ♂ (IVF) = 34.1 yr ± 4.236 ♂ control = 33.3 yr ± 2.7 | Cross-sectional. PFA, FIAI, STAI, KSP, EPDS | Results at 2 mo. postpartum: EPDS: IVF ♂ = 3.3 ± 3.2. Control ♂ = 3.4 ± 2.6. STAI: IVF ♂ = 28.3 ± 5.8. Control ♂ = 26.9 ± 5.2 | None of the control ♂ but 7.5% of the IVF men scored 10 or more on the EPDS. |

| [48] | 199 ♂T0: antenatally T1: 6 wks postnatally | Longitudinal. Trait section of STAI, PLDS, PCS antenatally. PTSD-Q, IES, state section of STAI, EPDS at T1 | EPDS score: 8% = 3.7 ± 4.1 State anxiety STAI-Y1: 6.6% = 32.1 ± 9.9; Clinically significant PTSD in at least one dimension (intrusions, avoidance, and hyperarousal) in 12% of participants | No evidence of PTSD in expecting fathers; rates of depression and anxiety quite low. |

| [49] | 270 ♀ and 213 ♂; ♀age ≤ 19: 13.4%; 20–29: 44.5%; 30–39: 40%; ≥40: 2.1%. ♂age ≤ 19: 4.4%; 20–29: 39%; 30–39: 48.2%; ≥40: 8.4% | Longitudinal. T0: 1st trimester; T1: 2nd trimester; T2: 3rd trimester. STAI, EPDS (cutoff >10) | STAI ♀ score: T0: = 36.16 ± 9.00; T1: = 34.69 ± 9.40; T2: = 36.33 ± 9.12. STAI ♂ score: T0: = 32.66 ± 8.43; T1: = 31.13 ± 7.98; T2: = 32.77 ± 7.94. EPDS ♀ score: T0: = 6.55 ± 4.22; T1: = 6.17 ± 4.39; T2: = 5.63 ± 4.27. EPDS ♂ score: T0: = 5.11 ± 3.97; T1: = 4.22 ± 3.38; T2: = 4.09 ± 3.32. | Symptoms of anxiety were higher in T0, ↓ in T1 and ↑ in T2. Symptoms of depression ↓ throughout pregnancy, with a significant ↓ occurring from the T0 to the T1 and again from the T1 to the T2. it is noteworthy that the T2 seems to be a period of relative calm in terms of psychological morbidity, and significant ↓ both in anxiety and depression symptoms were observed. |

| [50] | ART parents. T1: 2nd trimester 460 ART couples, 400 controls. T2: 2 mo postpartum 396 ART (324 singletons, 91 twins’ pairs), 319 controls (304 singletons, 20 twin pairs). T3: 1 yr postpartum 325 ART (270 singletons, 55 twin pairs), 262 controls (251 singletons, 11 twin pairs). ART group age: 90 ♀ of twins = 31.7 yr ± 4.0; 364 ♀ of singletons = 33.0 yr ± 4.2. 85 ♂ of twins = 33.7 yr ± 4.5; 357 ♂ of singletons = 35.0 yr ± 5.8.Control group age: 20 ♀ of twins = 33.1 yr ± 5.3; 379 ♀ of singletons = 33.3 yr ± 3.0. 20 ♂ of twins = 32.9 yr ± 5.4; 379 ♂ of singletons = 34.2 yr ± 5.4 | Longitudinal. GHQ-36 | ART ♂ of twins group score: T1 Depression 1.24, Anxiety 1.44, Sleeping difficulties 1.72; T2 Depression 1.26, Anxiety 1.38, Sleeping difficulties 1.66; T3 Depression 1.36, Anxiety 1.50, sleeping difficulties 1.76.ART ♂ of singletons group score: T1 Depression 1.22, Anxiety 1.38, Sleeping difficulties 1.65; T2 Depression 1.22, Anxiety 1.34, Sleeping difficulties 1.87; T3 Depression 1.28, Anxiety 1.36, sleeping difficulties 1.60.CONTROL ♂ of twins group score: T1 Depression 1.27, Anxiety 1.46, Sleeping difficulties 1.72; T2 Depression 1.37, Anxiety 1.53, Sleeping difficulties 1.87; T3 Depression 1.41, Anxiety 1.59, sleeping difficulties 2.00.CONTROL ♂ of singletons group score: T1 Depression 1.29, Anxiety 1.44, Sleeping difficulties 1.61; T2 Depression 1.26, Anxiety 1.39, Sleeping difficulties 1.62; T3 Depression 1.28, Anxiety 1.36, sleeping difficulties 1.59. | ART mothers of twins reported fewer symptoms of depression than control mothers of twins during pregnancy. The higher levels of depression and anxiety after delivery in both ART and control mothers of twins than in mothers of singletons confirm previous findings of an increased risk of post-partum depression associated with spontaneously conceived multiple births. Twin birth, but not ART, had a negative impact on the mental health of fathers. |

| [51] | 130 ♀ and 130 ♂. ♀ = 29.34 yr ± 2.96; ♂ = 31.92 yr ± 3.15 | Cross-sectional. EPDS (cut-off ≥ 13), PSS, SSRS, | EPDS score ≥13: 13.8% ♀ 8.44 ± 3.88 (range 3–23), 10.8%♂ 7.95 ± 3.60 (range 3–19). SSRS ♀ 35.32 ± 3.96; ♂ 8.48 ± 6.34. PSS ♀ 16.82 ± 4.33; ♂ 16.91 ± 3.67. | Results show no significant differences between paternal and maternal EPDS scores which indicates that depression is a problem for both women and men in the postpartum period. no significant differences between paternal and maternal perceived stress as indicated by the PSS scores. |

| [52] | 87 couples. ♀ = 28.95 yr (range 20–37); ♂ = 30.98 yr (range 21 to 43) | Cross-sectional. PBI, IRS, STAXI, CES-D, ways of coping-R, infant crying questionnaire. | ♀ scores: Emotional minimization: 1.82 ± 0.53; global empathy: 3.80 ± 0.46; trait anger: 1.88 ± 0.55; depression: 1.51 ± 0.32. ♂ scores: Emotional minimization: 1.89 ± 0.52; global empathy: 3.66 ± 0.53; trait anger: 1.81 ± 0.53; depression: 1.43 ± 0.31 | Depressive symptoms were linked with more parent-oriented beliefs about crying for fathers, supporting the notion that the pattern of affect and cognition affiliated with depression undermines an orientation toward others’ needs. |

| [53] | 178 mothers, 146 fathers (Japan) | Cross-sectional. 4 wk after birth: EPDS ≥ 8, CES-D ≥ 16 | 14% depression; no association between maternal and paternal depression. Paternal depression associated with employment status, history of psychiatric trtm, and unintended pregnancy. 8 fathers with unstable employment (7 temporary employees, 1 unemployed) | Perinatal care providers should independently screen for depression in fathers and mothers and focus attention on paternal employment status, especially temporary employment |

| [54] | Prospective cohort. 551 ♂ 33.4 yr ± 5.9 (18–59). 57♂ who dropped out at 8 wks post-partum 32.4 yr ± 5.5 | Cross-sectional. EPDS, BDI, PHQ-9. All participants who scored above the BDI cut-off score of 10.5 or the EPDS cut-off score of 9.5 were invited to return for a psychiatric diagnostic interview (SCID-NP) | Score of groups who completed the study: EPDS 4.9 ± 4.3. BDI: 3.8 ± 5.0; Score of groups who dropped: EPDS 5.4 ± 5.2. BDI: 5.2 ± 7.1 | Evidence suggested that postnatal depression in ♂ may have a later onset, probably following the occurrence of depressive symptoms in their partners. In contrast to ♀ who reported relatively high rates of depression during pregnancy and immediately following childbirth, depression in ♂ tends to ↑ over the first postnatal yr and reaches its peak at 12 months postpartum. |

| [55] | Recruited from 2 different hospitals. Hospital A: 469 ♀ 30.7 yr ± 5.0; 307♂ 32.0 yr ± 5.8. Hospital B: 394 ♀ 29.8 yr ± 5.2; 218♂ 31.8 yr ± 5.3 | Cross-sectional. EPDS, WPBL-R | EPDS scores: hospital A ♀: 6.6 ± 4.2 (≥13: 9%) ♂ 3.3 ± 2.9 (≥13: 1.3%). hospital B ♀: 6.9 ± 4.5 (≥13: 12.2%) ♂ 3.3 ± 3.4 (≥13: 2.8%) | Self-concept, depressive symptoms, infant centrality and parent’s state of mind on discharge emerged as the most significant parent attributes affecting mothers’ and fathers’ parenting satisfaction. |

| [56] | 189 ♂ 35.0 yr ± 5.86 and 184 ♀33.3 yr ± 4.84 | Cross-sectional. EPDS, SCID, Fathers depression was diagnosed by clinical interview. | Depressed ♂ EPDS score: 14.79 ± 3.41. non depressed: 6.64 ± 4.40 | Depression in ♂ after the birth of the child is associated with an adverse impact on child development, independently of the ♀’sMood. |

| [57] | 1562 ♂ partners of severely peripartum depression women | Cross-sectional. SCL-90 | 35% of partners scored high on depression items of the SCL-90 | About 35% of expecting fathers share their partner’s depressive mood |

| [58] | Cohort study. 687 ♀ 669 ♂ Subjects who participatedat all of three phases were included, 420 (61.13%) ♀ and409 (61.14%) ♂. T1: 3rd trimester of pregnancy; T2: 3 mo post partum; T3: 12 mo postpartum | Longitudinal. EPDS (cut off ≥ 11), ENRICH Marital Satisfaction Scale, The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire | 77.9% ♀ and 87.8% ♂ report no increase of depression from 28 and 31 weeks of pregnancy to 12 months post-partum. The incidence of depression during 12 mo post-partum was higher among ♀ and ♂ with low marital satisfaction (14.7% and 8.8%, respectively), low affective social support (17.8% and 10.3%, respectively), low confidant social support (22.5% and 10.9%, respectively), and with pregnancy depression (32.7% and 33.3%, respectively). Also, this incidence was higher when the partner of either sex was depressed (27.8% in ♀ and 16.3% in ♂) | The incidence of depression was higher among ♀ than ♂at T2, but was similar among ♀ and ♂at T3; the incidence of depression ↓ during the first postpartum year for ♀, but the association is at the limit of statistical significance; psychosocial and personal factors associated with depression 1 year after childbirth were similar for both ♀ ♂ (marital satisfaction, partner’s depression, pregnancy depression), negative life events were only related to ♀’s depression. Lack of affective and confidant social support did not increase the risk of depression in either ♀ ♂. |

| [59] | 739 fathers | Longitudinal. PPD and BD prevalence in fathers; MINI: T1(28–34 wk), T2(30–60 postpartum), T3(12 mo postpartum) | Depression: 5%, 4.5%. 4.3%; BD: 3%. 1.7%. 0.9%. Depressive episodes in fathers significantly associated with manic/hypomanic episodes during pregnancy and postpartum period; not 12 mo after birth. Delivery may act as a specific event whose effects decrease over time | Bipolar episodes were common in men with depressive symptoms during their partner’s pregnancy in the postpartum period and, to a lesser extent, 12 mo after birth. This population should be carefully investigated for manic and hypomanic symptoms. The high prevalence of bipolar related episodes may depend on the instrument used and on this specific period of life which might act as a stressor in association with genetic vulnerability, increasing the risk of highly heritable forms of affective disorders |

| [60] | 1562 ♂ 7 weeks postpartum | Cross-sectional. EPDS, SCID | EPDS score: 335 (85.6%) scored ≤ 10 and 199 (12.74%) scored ≥ 10. A random selection of the EPDS low scorers (n = 266) and all the EPDS high scorers (n = 199) were contacted to obtain permission to be assessed using the SCID diagnostic tool for depression. Thirty-one (16%) ♂ met the DSM-IV criteria for depression while 94 (49%) ♂ failed to meet these criteria. Sixty- seven (35%) ♂ were not currently depressed but were deemed at ↑ risk of developing depression. | The main finding of this study suggests that depression in ♂ in the postnatal period is associated with increased healthcare costs. In terms of incremental costs for each category of care, depression was associated with significantly ↑ community care costs |

| [61] | 99 fathers with diagnosed depressive disorders, 54 w/o | Cross-sectional. To investigate association between paternal depressive disorder and family and child functioning in the first 3 mo of a child life (families seen at home 3 mo after birth). SCID, EPDS ≥ 10, AUDIT, DAS, IBQ, antisocial personality problems scale, perceived criticism in the couple relationship self-report. | Depression in fathers is associated with an increased risk of disharmony in partner relationship, reported by both fathers and their partners, controlling for maternal depression. Few differences in infant’s reported temperament found in the early postnatal period | Depressive disorder affecting fathers is associated with an increased risk of inter-parental conflict in the postnatal period. Paternal depression. Paternal depression seems to be associated with somewhat higher levels of difficulties in infant temperament |

| [62] | 260 couples. ♀ age ≤ 19: 11.8%; 20–29: 46.7%; 30–39: 39, 5%; ≥40: 2.0%. ♂ age ≤ 19: 4.4%; 20–29: 39.0%; 30–39: 48, 2%; ≥40: 8.4%. | Longitudinal. STAI-S, EPDS ≥ 10. T0: 1st trimester; T1: 2nd trimester; T2: 3rd trimester; T3: 1–3d afterbirth; T4: 3 mo postpartum | STAI-S ♀ scores: T0: 13.1%; T1: 12.2%; T2: 18.2%; T3: 18.6%; T4: 4.7%. ♂ scores: T0: 10.1%; T1: 8.0%; T2: 7.8%; T3: 8.5%; T4: 4.4%. EPDS ♀ scores: T0: 20.0%; T1: 19.6%; T2: 17.4%; T3: 17.6%; T4: 11.1%. ♂ scores: T0: 11.3%; T1: 6.6%; T2: 5.5%; T3: 7.5%; T4: 7.2%. | Results generally show ↑ rates of depression compared to anxiety, in ♀ compared to ♂, and during pregnancy compared to T4. Depression was more prevalent than high-anxiety in ♀ either early in pregnancy or at T4. ♀ were more likely than men to show high-anxiety at T2 and at T3, but not during early pregnancy or T4. |

| [63] | 185 ♀ 30.9 yr ± 5.5 (16.4–43.8) 140 ♂ 33.0 yr ± 6.4 (19.7–52.5) | Cross-sectional. M-PHI or F-PHI, SF-12 (MCS, PCS), EPDS, WEMWBS | ♀ scores: EPDS: 6.9 ± 5.2 (0.0–23.0); WEMWBS: 50.6 ± 8.6 (27–70); SF-12 MCS: 48.5 ± 10.0 (17.1–64.1); SF-12 PCS: 53.0 ± 6.5 (29.5–62.9).♂ scores: EPDS: 4.3 ± 4.0 (0.0–18.0); WEMWBS: 53.5 ± 9.0 (29–70); SF-12 MCS: 52.0 ± 7.1 (30.6–62.0); SF-12 PCS: 53.3 ± 5. (28.8–62.4) | This was a validation study; M-PHI and F-PHI showed fair convergence with other instruments, especially the EPDS |

| [64] | 376 parents. ♀ 26.64 yr ± 3.38 (21–36); ♂ 27.09 yr ± 4.46 (22–39) | Cross-sectional. PSS, SSRS, EPDS ≥ 13. | PSS scores ♀ 17.16 ± 3.75; ♂ 16.03 ± 3.67. SSRS scores ♀ 38.53 ± 5.56; ♂ 35.43 ± 4.87. EPDS scores ♀ 8.62 ± 3.88; ♂ 8.03 ± 3.60 | There were no significant differences in the prevalence of PND or EPDS scores between the new ♀ and ♂. The results showed that there was no significant difference between ♀ and ♂ perceived stress, indicating that the ♂ experienced similar levels of stress as ♀ at postnatal period. Perceived stress and social support were key predictors of EPDS scores for both ♀ and ♂ during the postnatal period. |

| [65] | Prospective cohort study. 551 couples. ♂ 33.4 yr ± 5.9 | Cross-sectional. EPDS, BDI, SCID | Prevalence of PND 4.9% (2.4% major and 2.5% minor) | Postnatal depression in one partner correlated with postnatal depression in the other. This association has been consistently demonstrated but is not likely to be related to common risk factors. ♂ postnatal depression was predicted by life events and stress. |

| [66] | 650 ♂ | Longitudinal. MINI | 2.6% of ♂ were depressed | Suicide risk in ♂ ↑ from prepartum to postpartum |

| [67] | 303 couples at T1: within the first seven days of the birth. 227 couples T2: 6 wks post-partum. 231 couples T3: 3 mo. 220 couples completed all 3 time points. ♀ 31.7 yr (19–44) ♂ 34.3 yr (21–56) | Longitudinal. IES, PTSD-Q, EPDS, STAI, SOS, ECR | ♀ EPDS score: T2: 7.14 ± 4.87. T3: 7.14 ± 4.87. ♂ EPDS score: T2: 3.94 ± 3.96. T3: 3.41 ± 4.02; ♀ STAI score: T1: 35.55 ± 8.34. ♂ STAI score: T2: 34.45 ± 7.64. | ♀ appeared to be differentially adversely affected by ♂ early symptoms; ↑ levels of acute symptoms in ♂ appeared to be particularly linked to ♀ later distress while the reverse was not true for ♂. Symptoms of post-traumatic stress and postpartum depression were positively related within couples. |

| [68] | RCT study. Intervention consisting in education sessions. 1574 individuals in a couple relationship (862 ♀ 712 ♂). 315♂ control 29.4 yr (17–54); 365♂ intervention 29.5 yr (16–51). At 6 wks 556 ♂ (253 control, 303 intervention) | Longitudinal. HADS-A, HADS-D. As part of that trial a repeated measures cohort study was conducted to identify changes in self reported levels of anxiety and depression between the ♂ in the intervention group and the ♂ in the control group from bl to six wks | ↓ anxiety levels from bl to 6 wks were significant in the intervention group but were not significant in the control group. In the intervention group 12.4% of the ♂ had less anxiety from bl to six weeks postnatal compared to 11.4% of ♂ in the control group. Both the intervention and control groups reported ↓ antenatal anxiety at 6 wks postpartum the antenatal and postnatal depression scores remained unchanged at 4% in both groups. | The intervention may have contributed to the ↓ anxiety scores in the intervention group by providing timely, relevant information to assist the fathers. Most of the fathers in both groups did not register any depression either ante or postnatal with no real changes from bl 6 wks post test, suggesting that depression levels remained constant. |

| [69] | 231♂ = 31 yr ± 6.3 (range 20 to 49) | Cross-sectional. SCID, CAGE Questionnaire | SCID results: Prevalence of any mental disorders 17.7%; Depressive episode 5.2%; Panic disorder 0.9%; Generalised anxiety disorder 4.3%; Co-morbid anxiety disorder and depression 5.2%. | The prevalence of any depressive disorder in ♂ in this study (12.6%) is ↑ than the pooled prevalence in high-income countries (9%) and much ↑ than in the studies which used the same diagnostic assessment in well-resourced Asian countries: Singapore (1.8%) and Hong Kong (3.1%). Panic and generalised anxiety disorders were apparent in 10.4%, but there are no data from other resource-constrained settings with which these can be compared. |

| [70] | Extensive cohort study. Bl fist visit to child health center, T1: 3 mo postpartum. 305 couples. Depressed ♀ 30.6 yr ± 4.46; Non depressed ♀ 29.9 yr ± 5.03. Depressed ♂ 32.5 yr ± 5.15; Non depressed ♂ 33.0 yr ± 5.65 | Longitudinal. At bl: DCS, DAS. T1: EPDS | 260 ♀ and 252 ♂ had answered all EPDS questions. 16.5% of ♀ and 8.7% of ♂ sufferedfrom postpartum depressive symptoms according to the EPDS cut-off of >9. ♀ and ♂ with depressive symptoms scored ↑ levels of discord compared to parents without depressive symptoms. | 16.5% of the ♀ and 8.7% of the ♂ self-reported depressive symptoms. Results indicated that nearly a quarter (23%) of the children had at least one parent with postpartum depressive symptoms. |

| [71] | 199 couples. ♂ 36.44 yr ± 7.22; ♀ 34.53 yr ± 4.43 | Cross-sectional. EPDS (9/10 cutoff), EPDS-P (partner report), IDD | EPDS depression ♂: 12.6%; IDD depression ♂: 4.5% | The EPDS-P was found to be a reliable and valid measure of paternal depression based on the measure’s internal consistency and the measure’s relation with other well-validated measures of depression. |

| [72] | 1403 ♂. Age 18–20: 11.26% (158); 21–25: 29.01 (407); 26+: 59.73% (838). Interviewed at the birth of a child and followed up when the child was 1, 3, and 5 years old. | Longitudinal. CIDI-SF, paternal involvment, PSI, marital relationship. | Age 18–20 score ♂ depression case 1st year 8% (67); 3rd year 10.50% (88); 5th year 9.67% (81). Depressive symptoms score 1st year: none: 91.41% (766); score 1–2: 0.60% (5); score 3–8: 8% (67). 3rd year: none: 91.41% (766); score 1–2: 0.60% (5); score 3–8: 8% (67). 5th year none: 90.10% (755); score 1–2: 0.24% (2); score 3–8: 9.67% (81). Age 21–25 score ♂ depression case 1st year 10.07% (41); 3rd year 13.27% (54); 5th year 11.79% (48). Depressive symptoms score 1st year: none: 88.21% (359); score 1–2: 1.72% (7); score 3–8: 10.07% (41). 3rd year: none: 85.15% (344); score 1–2: 1.49% (6); score 3–8: 13.37% (54). 5th year none: 87.22% (355); score 1–2: 0.98% (4); score 3–8: 11.79% (48). Age 26+ score ♂ depression case 1st year 9.49% (15); 3rd year 16.46% (26); 5th year 12.03% (19). Depressive symptoms score 1st year: none: 87.97% (139); score 1–2: 2.53% (4); score 3–8: 9.49% (15). 3rd year: none: 81.41% (127); score 1–2: 1.92% (3); score 3–8: 16.67% (26). 5th year none: 87.34% (138); score 1–2: 0.63% (1); score 3–8: 12.03% (19) | Emerging adult fatherhood was not related to depression. Rates roughly ranged from 8–16%, depending on the age status of fathers and in which year the depressive symptoms were measured. Late adolescent fatherhood, was a significant predictor of third-year depression. Late adolescent fathers have a 2-fold risk for depression than adult fathers when their children were about 3 years-old |

| [73] | 231 ♂ 31 yr ± 6.3 | Cross-sectional. SCID | SCID major depression or dysthymia: 7.4% of ♂; generalized anxiety: 5.2% ♂; co-morbid depression and anxiety: 5.2% of ♂ | This study is mean to establish the validity of a group of psychometric instruments. The selected cut-off points for EPDS in ♂ was 4/5, one point higher than that in ♀. The optimal cut-off for each scale was selected as the score that produced the maximum combination of Se and Sp |

| [74] | Cohort study. T1: 18 wk gestation; T2: 8 mo. postnatally. 11,954 ♀ and 9846 ♂ | Longitudinal. EPDS cut off ≥ 12 | EPDS score ≥ 12 T1: 13.8% of ♀, 4% of ♂. T2: 8.8% of ♀, 2.9% of ♂. 360 ♀ and 59 ♂ were depressed at both T1 and T2 | Parental depression in the postnatal period was associated with adverse child outcomes. Postnatal ♂ depression was found to predict later total problems and conduct difficulties in children |

| [75] | 296 young couple♀ 18.7 yr ± 1.63 (14–21), ♂ 21.3 yr ± 4.06; Couples completed interviews via separate audio computer-assisted self interviews | Cross-sectional. LES, 15 of 20 items of CES-D | Depression: ♀ 10.55 ± 7.39; ♂ 8.88 ± 6.62 | Among both young ♀ ♂, the relationship between stressful life events and depression disappeared among those with the highest amount of social support. For ♂ with the most family functioning, stressful life events had the strongest association with increased depression, although the trend across levels of family functioning was slight and less dramatic compared to ♀. |

| [76] | This study uses data collected in a randomized controlled trial. 812 ♂ 31 yr ± 2 yr. The sample was divided in groups by the age: ≤28: 240; 29–33: 354; ≥34: 218 | Cross-sectional. EPDS at 3 mo after birth. (cut-off ≥ 11) | Elevated score on the EPDS: ♂ ≤ 28 yr of age: 16.3%; ♂ 29–33 yr: 7.1%; ♂ ≥ 34 yr: 8.7%. Total depression 10.25% | ♂ aged 28 years and younger had a more than twofold ↑ risk of depressive symptoms 3 mo. after the birth compared with ♂ 29–33 years of age, whereas ♂ aged 34 years and older had no ↑ risk. Factors associated with an ↑ risk for depressive symptoms included having a low income, low level of education, poor partner relationship quality, and worries about economy and employment |

| [77] | 199 couples completed BL interviews at 4 wk postpartum, 172 couples at 6 mo postpartum. All couples completed separate computer-assisted telephone interviews. ♀ 30.6 ± 5.0; ♂ 32.8 ± 5.6 | Longitudinal. CIDI, EPDS (cut-off ≥ 9 for ♀; ≥10 for ♂) | 9.3% ♀ 4.1% ♂ had at least one anxiety disorder; a total of 57 ♀ (33.1%) and 30 ♂ (17.4%) met criteria for at least one common mental disorder in the first 6 months postpartum. EPDS scores at 6 mo postpartum: ♀ 4.3; ♂ 3.4 | EPDS scores of women and men did not correlate significantly. ♀ EPDS scores at 6 mo postpartum were significantly ↑ than ♂ |

| [78] | T1 18–20 wks prepartum: 153 couples; T2 32–34 wks prepartum: 153 couples; T3 3 mo postpartum: 127 couples | Longitudinal. EPDS, STAI, PRAQ. | EPDS scores: T1 ♀ 5.3; ♂ 4.0; T2: ♀ 5.1; ♂ 3.3; T3: ♀ 4.6; ♂ 3.6. STAI scores: T1 ♀ 31.3; ♂ 29.8; T2: ♀ 32.9; ♂ 30.0; T3: ♀ 31.2; ♂ 30.0. | The EPDS and STAI scores in this study were slightly lower than in two Australian studies that also included pregnant mothers and fathers. |

| [79] | 262 ♂ | Cross-sectional. Prime-MD | 47 of 262 ♂ satisfied the criteria for Prime-MD depression or anxiety, 18 depression (2 major and 16 minor), 11 with co-morbid depression and anxiety (6 major, 4 minor and 1 dysthymia), 18 with anxiety only | The study aimed to evaluate how well the EPDS identify depression and anxiety in ♂ |

| [80] | 205 ♂; child age = 11 mo (Québec) | Cross-sectional. A descriptive-correlational study. Psychosocial factors associated with PPD: EPDS ≥ 10, DAS, PES, PSI | 8.2% ♂ (infants brestfed ≥ 6 mo) positive to EPDS 8–14 mo after birth. Quality of spousal relationship associated with paternal depression 3 mo after birth persists over time. ♂ in depressed group reported ↑ levels of parenting distress and lower sense of parenting efficacy. Depression in fathers of breastfed infants is associated with the experience of perinatal loss in a previous pregnancy, parenting distress, infant temperament, dysfunctional interactions with child, decreased marital adjustment and perceived low parenting efficacy | ♂ depression associated with certain psychosocial factors. The depressed ♂ reported lower quality of marital relationship, perception of lower parenting efficacy and greater parenting distress. These finding indicate the importance of screening for postnatal depression among ♂ of breastfed infants, not only in the wks following the birth of the child, but throughout the first-year f the child’s life |

| [81] | 64 couples. ♀ 29.0 yr ± 3.5; ♂ 30.0 yr ± 6.0. T1: 1 mo postpartum; T2: 6 mo postpartum; T3: 12 mo postpartum. | Longitudinal. EPDS (cut-off of ≥13 for major depression), SCID | ♀ EPDS score: T1 4.4 ± 0.6; T2 4.7 ± 0.5; T3 4.8 ± 0.5. ♂SCID score: Substance abuse 32.3%; Anxiety disorders 9.7%; Mood disorders 29.0%; Psychosis 3.2%; Comorbid-mood /substance abuse 25.8% | While ♀ depressive symptoms were correlated throughout the first twelve months postpartum, ♂’s mental health moderated the course of these symptoms. Separate from ♀ history of depression, a ♂ substance abuse-related Axis I diagnosis was associated with augmented ♀ depressive symptoms, relative to a ♂ mood related diagnosis or no ♂ diagnosis. The psychiatric lifetime history of the ♂ may be a critical piece in the regulation of maternal depression. According to ♂ lifetime psychiatric interviews, 48.4% of ♂ had a lifetime history of mental1 illness |

| [82] | 393 couples; 401 ♀ 30 yr ± 5; 396 ♂ 33 yr ± 6; T0: (demographic data) = 393 couples); T1: (3 mo. Post-partum) = 308 couples; T2: (18 mo. Post-partum) = 272 couples | Longitudinal. EPDS >9; SOC; ICQ | Depressive symptoms measured at T1 = 17.7% ♀; ♂ 8.7% and correlated between mothers and fathers within couples. Mothers and fathers with depressive symptoms had a poorer sense of coherence and perceived their child’s temperament as more difficult than mothers and fathers without depressive symptoms at 3 and 18 months. Post-partum depressive symptoms did not differ according to the parents’ age, child’s sex, first or not first child, SES or mothers’ educational level. | Early parenthood has been studied thoroughly in mothers, but few studies have included fathers. Depressive symptoms were more common in fathers with senior high school educational level compared with those with higher education or 9-year compulsory school |

| [83] | 349 ♀ (first-time) 270♀, 122 ♂ (Longitudinal sample) | Longitudinal. EPDS, CBCLT0 = prenatally T1 = 2 mo postnatally T2 = 6 mo postnatally T3 = 8–9 yr postnatally | The differences between ♂ and ♀ views remained significant considering both internalizing and externalizing problems in boys, and nearly significant regarding internalizing problems in girls. Regarding ♂ reports, ♀ depressive symptoms was associated with significantly elevated level of child’s total and externalizing problems. According to ♀ reports, the finding was similar but for total problems, the difference lacks statistical significance. For internalizing problems, the difference between the groups with and without ♀ depressive symptoms was not significant according to either of the parents | This study aimed at examining the specific view of ♂ and agreement between parental views considering the competence and emotional/behavioural symptoms of their child and the impact of ♀ depressive symptoms on parental perceptions. The findings in this study showed that ♀depressive symptoms affect the child, also from the ♂ perspective |

| [84] | 110 couples. ♂ 31.9 yr ± 5.02 ♀ 28.6 yr ± 4.89 | Cross-sectional. FIF, MIF, EPDS | The medical problems in pregnancy: 33.6%. 48.2% of ♀ reported anxiety about motherhood. This rate was 32.7% for ♂ because of a new baby. The proportion of PPD was 9.1% ♀. 1.8% ♂. The previous history of the depression was 7.3% ♀. 0.9% ♂. 17.3% ♀ had a history of depression in close relatives, and this proportion 9.2% ♂. EPDS: ♀4.29 ± 5.33; ♂1.12 ± 2.75 | PPD is a serious problem that affects ♀ health and well-being marital relationship as well as offspring’s health and well-being |

| [85] | 163 ♂; 163 ♀ | Longitudinal. T1 = 3 mo.; T2 12 mo. (DAS; EPDS) | ♀♂ were found to display quite similar EE scores. Regression analyses showed that depression and couple relationship significantly predicted EE in ♀, but not ♂. High levels of depressive symptoms in ♀ predicted increased critical comments in ♂ and less warmth with their children | The findings of the present study are of potential clinical importance, as the parenting characteristics identified by the assessment of EE and its constituent components are potentially amenable to clinical intervention. As these findings relate to the first year of a child’s life the possibility is raised of useful early intervention for depressed parents and their children |

| [86] | 205 ♂ 32.63 yr ± 5.00 | Cross-sectional. EPDS, PSS, MSPSS. | EPDS score: 5.77 ± 4.50. PSS score: 45.36 ± 8.06. MSPSS score: 12.21 ± 6.55 | The frequency of depression in ♂ was 11.7%. Increase in the ♂’s stress score was associated with increased rates of depression in them. The regression analysis suggested that perceived stress as a factor effecting depression is of high importance in predicting ♂’s PPD |

| [87] | BiT study, ‘Barnhälsovård i Tiden’ [Child Health Care Today]. Longitudinal cohort study. T1: 1 wks post-partum 401 ♀ 396 ♂. T2: 3 mo post-partum 336 ♀ 333 ♂T3: 18 mo post-partum320♀ 314 ♂T4: 6–8 yr after childbirth 391 couples | Longitudinal. EPDS, SOC-3, SPSQ | T2: EPDS score ≥ 10 = 17.7% 59 ♀, 8.7% 28 ♂EPDS score ≥ 12 = 9.9% 33 ♀ and 5.0% 16 ♂. The main finding of the present study is the association between the time to marital separation and ♂ dyadic discord, mothers’ and/or fathers’ depressive symptoms, and ♀ parental stress during early parenthood. ♀♂selfestimated less dyadic consensus, more depressive symptoms, and higher parental stress than those who were not separated. | The data from the present study showed an association between low dyadic consensus, depressive symptoms and parental stress during early parenthood, and an increased risk of marital separation 6–8 years after childbirth. This knowledge is important for health professionals and could be useful in developing interventions to provide parents with adequate support during pregnancy and early parenthood |

| [88] | 622 ♂ T0: 12 wks gestation; 337 ♂ T1: 36 wks gestation; 150 ♂ T2: 6 mo postpartum. A total of 187 participants completedall three time points of the survey. ♂ 34.19 yr ± 5.21 (19–55) | Longitudinal. EPDS > 12/13, MSPSS, RSE | EPDS scores: T0: 5.22 ± 3.59; T1: 5.23 ± 3.67; T2: 5.15 ± 4.17. | Using ≥13 as the standardized cut-off for probable case of depression, the prevalence increased as the pregnancy progress and reached a peak at T2, with 3.3% of the participants scoring above cut-off in T0, 4.1% in T1 and 5.2% in T3, respectively. ♂ antenatal depression, especially ♂ depression in late pregnancy, could significantly predict ↑ level of depression among the expectant ♂ in the postpartum period. |

| [89] | 102 ♂ recruited between the second (>24th week) and third trimester of their partner’s pregnancy. ♂ 35.82 yr ± 5.95 (23–55) | Longitudinal. EPDS (T0: between the 2nd and 3rd trimester of pregnancy; T1: 4–6 wks postpartum) cut-off > 9, STAI. | EPDS score: T0: 4.17 ± 3.59; T1: 4.04 ± 3.23. STAI scores: 49.61 ± 11.19 | 9.8% of the expectant ♂ showed signs of elevated depressive symptoms during their partner’s pregnancy by having scores of 9 or more on the EPDS and are therefore at risk of being diagnosed with a minor or major depressive disorder. Considering our results, on the one hand, this could imply that after adjusting to the new life circumstances, fewer fathers tend to suffer from depressive symptoms postnatally compared to the prepartum which is consistent with the findings of previous studies. |

| [90] | 172 couples | Cross-sectional. EPDS cut-off >12, VPSQ, RLCQ | Perceiving the partner as more controlling was significantly associated with more depressive symptoms in the individual but also in his or her partner. Perceiving the partner as more caring was not significantly associated with fewer symptoms in either the individual or the partner, once other relevant variables were controlled for. Higher levels of depressive symptoms were also associated with having a more vulnerable personality, other coincidental stressful life events and having a more unsettled baby | ♀♂ vulnerable personality traits, coincidental adverse life events and more infant crying and fussing were also associated with significantly more depressive symptoms. The quality of the intimate partner relationship is significantly associated with postnatal mental health in both women and men, especially in the context of coincidental stressful events including infant crying |

| [91] | 18,552 from the Millenium Cohort Study (MCS) | Longitudinal. T1(9 mo): Rutter’s 9-item Malaise Inventory (shortened version) T2 (3 yr): Child-Parent Relationship ScaleT3 (5 yr)/T4 (7 yr): Fathers’ parenting activity (involvement) was measured using answers to the amount of parenting activities they undertook with their child | Findings suggest that postnatal paternal depressive symptoms are associated with fathers’ negative parenting. Paternal depressive symptoms significantly predicted higher levels of father-child conflict. Paternal depressive symptoms were not associated with paternal involvement, suggesting that the quality of parenting is influenced by depressive symptoms, but the duration of time spent with the child is not altered. Both maternal depressive symptoms and marital conflict moderated the association between paternal depressive symptoms and father-child conflict | Despite reports showing the huge costs of paternal depression, parenting interventions are still primarily targeted towards mothers. Authors advocate a more family-centred approach and provided that appropriate support and services are put in place, they suggest routine screening for postnatal depressive symptoms in fathers |

| [92] | 897 families; the sample was divided into three groups: (Group A) families with ♀ who have experienced physical/sexual abuse (32.8 yr ± 2.2); (Group B) ♀ with experienced emotional abuse/neglect (33.4 yr ± 2.5); (Group C) ♀ no traumatic experiences (31.4 ± 2.2). | Longitudinal. T0: SCL-90-RT1/T2: SCL-90–9, SVIA | The results showed that ♀ with early traumatic experiences (Groups A and B) had significantly more maladaptive interactions during the feeding of their children, both at 3 mo and 6 mo of age, when compared to mothers who had not experienced traumas (Group C).SCL-90-R mothers’ subscale scores showed a main effect of the group with no time-point effect and no interaction effect between time point and group. The ♀ in Group B had significantly higher scores at T2 than Group A on the somatization, depression, and paranoid ideation subscales. The scores of the ♀ in Group C on all SCL-90-R subscales were significantly lower than those of Groups A and B, both at T1 and T2 | Some authors have suggested that sexual abuse can have a more severe impact on subjects’ psychopathology and has more frequently been associated with psychiatric diagnoses (e.g., PTSD). It has also been evidenced that ♀ victims of emotional abuse have a higher risk of psychopathological (including depressive) symptoms |

| [93] | 14,541 pregnant ♀ database; compared data of 418 mothers and 114 fathers with depression | Longitudinal. T0: 18 we gestation (the only timepoint at which mother to be and father to be depression levels were recorded) T1: 21 mo postpartum. EPDS cut-off > 13; CCEI cut-off ≥ 8; CIS-R | EPDS: 418 mothers (10.7%) and 114 fathers (3.3%) reported symptoms of antenatal depression; 725 mothers (16.8%) and 238 fathers (6.9%) reported symptoms of antenatal anxiety (CCEI). Children of mothers with high depressive symptoms at 18 weeks gestation had an increased risk of anxiety diagnosis at 18 | This study showed an increased risk of offspring anxiety at 18 years of age after exposure to maternal antenatal depression at 18 weeks gestation. This association was not seen following exposure to paternal depression. These findings highlight the differences between antenatal depression exposures in different parents. This adds to support for a fetal programming effect occurring during pregnancy, leading to potentially long-lasting effects on the anxiety state of offspring. |

| [94] | 53 couples ♂ = 34.45 yr ± 5.2 ♀ = 30.35 yr ± 5.6 | Cross-sectional. EPDS; PSI-SF | EPDS 20.8% ♀ 5.7♂ reported high risk of PPD; 18.9% of ♂ reported borderline scores indicating risk of subclinical PPD; ♂ reported very high scores both in global distress level. No significant correlation between parenting distress and the risk of PPD emerged, both in ♀ than in ♂ group while distress ♀ levels are related to paternal one. Additional analysis regarding the association between the desire of pregnancy and the level of PPD suggests that there is a significant difference between ♂who desired a child e ♂ who did not desire a child | During this critical life event, some of couples of parents experience a high vulnerability and refer significant distress levels; mood disturbances and parenting stress in postpartum period represent high risks of parents and children well-being. Dysfunctional parenting has been assumed as an important risk factor in the development of psychological disturbances in adulthood and several studies have reported a significant correlation between maternal PPD and altered cognitive/affective child development. |

| [95] | T1 2 wks postpartum: 317 ♀ (249 intervention group, 68 control group), 276 ♂ (210 intervention group, 66 control group). T2 6 mo postpartum: 216 ♀ (181 intervention group, 35 control group), 185 ♂ (152 intervention group, 33 control group). Total ♀ = 28.83 yr ± 5.22, IG ♀ = 28.83 yr ± 5.22, CG ♀ = 30.32 yr ± 5.18; Total ♂ = 32.18 yr ± 6.21, IG ♂ = 31.62 yr ± 6.28, CG ♂ = 33.96 yr ± 5.66 | Longitudinal. EPDS (≥ 13 for ♀, ≥ 11 for ♂) | T1 EPDS score: Total ♀ = 7.22 ± 5.06, IG ♀ = 7.14 yr ± 5.04, CG ♀ = 7.52 yr ± 5.14; Total ♂ = 4.27 yr ± 3.57, IG ♂ = 4.20 yr ± 3.41, CG ♂ = 4.51 yr ± 4.06. T2 EPDS score: Total ♀ = 5.19 ± 4.71, IG ♀ = 5.03 yr ± 4.54, CG ♀ = 6.07 yr ± 5.49; Total ♂ = 3.76 yr ± 3.67, IG ♂ = 3.98 yr ± 3.65, CG ♂ = 2.76 yr ± 3.67. | A significant number of parents reported high levels of psychological distress shortly after birth and at 6 mo. postpartum. |

| [96] | 1797 ♀, 1658 ♂ | Longitudinal. RDAS; SPIN; BDIT1: 20th pregnancy week. T2: 8 mo post-partum. T3: 18 months post-partum | The test-retest reliability correlations between consecutive measurement points were at least moderate indicating that both ♀ and ♂ social and emotional loneliness were stable during the study period. Concerning ♂ social loneliness, similarly to ♀ the largest class consisted of fathers with very low and even continuously decreasing feelings of loneliness. These groupings revealed that the higher the loneliness was, the more the parents experience these other psychosocial problems | Becoming a parent may increase both mothers’ as well as fathers’ feelings of social and emotional loneliness and these phenomena are highly associated with lower levels of marital satisfactions and higher levels of social phobia and depression |

| [97] | 807 couples | Cross-sectional. EPDS (♂ cut-off ≥ 8; ♀ cut-off ≥ 9) | EPDS ♂ scores: 110 (13.6%) scored ≥8. The age of these ♂ 33.4 ± 5.7 yr. | The prevalence of ♂ depression at four months after childbirth was 13.6%. The factors that were significantly correlated with ♂ depression were the presence of partner’s depression, low marital relationship satisfaction, pregnancy with infertility treatment, experience of visiting a medical institution due to a mental health problem, and economic anxiety |

| [98] | 230 families (230 ♀ = 32.6 yr ± 4.66; 173 ♂ = 35.8 yr ± 7.58) | Longitudinal. EPDS cut-off ≥ 13; BDI cut-off ≥ 18; SCID-I | ♀ Preterm EPDS T1 = 9.0 ± 5.69. Term EPDS T2 = 4.7 ± 4.14. Preterm BDI T1 = 9.2 ± 6.76) T2 = 5.2 ± 3.68) ♂ Preterm EPDS T1 = 5.7 ± 4.29 T2 = 3.0 ± 2.99. Term BDI T1 = 5.8 ± 4.30 T2 = 4.0 ± 3.59 | The risk of PPD was 4 to 18 times higher for mothers and 3–9 times higher for ♂ of VLBW infants compared to mothers and fathers of term infants. Mean scores on the depression scales and prevalences of clinical PPD were higher in parents of VLBW infants than in parents of term infants, with ♀ in both groups at a higher level than ♂. The most important risk factor for PPD was the birth of a VLBW infant itself. Family related factors like SES, primipara, a pregnancy of high risk or with multiples were not as relevant as individual parental factors like sex, lifetime psychiatric diagnoses and social support |

| [99] | Data were from four waves of the Personality and Total Health (PATH) Through Life Survey, a longitudinal, population-based survey assessing the health and well-being of the residents of Canberra and Queanbeyan (New South Wales) in Australia. The sample has been divided in EF (expectant father): 88 ♂ 22.7 yr ± 1.4; NF (new father) 108 ♂ 22.7 yr ± 1.5; AF (alredy father) 61 ♂ 23.4 yr ± 1.4 | Longitudinal. Goldberg Depression and Anxiety Scales, SF-12 | Depression score (0–9): EF: 2.0 ± 1.9; NF: 2.2 ± 2.1; AF: 2.7 ± 2.3. Anxiety score (0–9): EF: 2.7 ± 2.6; NF: 2.8 ± 2.5; AF: 3.5 ± 2.6. General mental health (0–100) EF: 50.8 ± 7.3; NF: 50.7 ± 8.9; AF: 49.5 ± 9.7. | The results showed that men experienced no greater depression or anxiety at the time of being a first-time expectant or new father, compared with levels prior to transition to fatherhood. In summary, this study finds first-time expectant and new fatherhood is not typically associated with increased levels of depression and anxiety |

| [100] | 192 ♂ = 35.04 yr ± 5.9 | Cross-sectional. EPDS at 7 wk postpartum, SCID at 3 mo postpartum | 54 ♂ met the SCID criteria for depression (19 with current depression, and 35 with a history of depression). ♂ with depression scored significantly ↑ on the EPDS ( = 14.79 ± 3.41) than non-depressed fathers ( = 6.64 ± 4.40) | Fathers with depression may be withdrawn while interacting with their infants and be less stimulating. They may adopt maladaptive patterns of parenting, thus potentially impairing their children’s development |

| [101] | N = 13,822 | Longitudinal. Cohort study EPDS > 12 at 8 wk and 8 mo after birth (both ♀ ♂). Child outcomes Rutter revised preschool: 42 and 81 mo. | Family factors (maternal depression and couple conflict) mediated 2/3 of the overall association between paternal depression and child outcomes at 3.5 yr. Similar findings when children were 7 yr old. In contrast, family factors mediated less than 1/4 of the association between maternal depression and child outcomes. No evidence of moderation effects of either parental education or antisocial traits. | This study suggests that the association between depression in ♂ during postnatal period and subsequent child behavior is explained predominantly by the mediating role of family factors. In contrast, the association between depression in ♀ and child outcomes is only explained to a small degree by these wider family factors and is better explained by other factors, which might include direct effects of depression on mother-infant interaction |

| [102] | 200 couples♀ = 32.3 yr ± 4.2 ♂ = 34.5 yr ± 4.7 T1 during pregnancy T2 6 mo postpartum | Longitudinal. GHQ, FSOC-S, SRRS, MOS-SSS, MOS-FMFM | Depressive symptoms, ♀ T1 15.5% T2 11.5%; ♂ T1 7.0% T2 10.5%; T1 ♀ > ♂. Predictor for depressive symptoms at postpartum, ♀ family sense of coherence, social support, and depressive symptoms during pregnancy changes in family sense of coherence and social support from pregnancy to 6 months postpartum; and partner’s depressive symptoms; ♂ family sense of coherence and depressive symptoms during pregnancy, changes in family sense of coherence from pregnancy to 6 months postpartum, and partner’s depressive symptoms were significant predictors of depressive symptoms at 6 months postpartum | Partner’s depressive symptoms significantly predict mothers’ ♂ depressive symptoms 6 months postpartum, suggesting that an increase in depression in one partner leads to increase in the other. Prenatal depression was a significant risk factor for postnatal depression among both parents. Social support was only found to predict depressive symptoms at postpartum among the mothers, but not the ♂. Mothers had a comparatively higher level of social support than the ♂ across the perinatal period indicating that social support acts as an important external coping resource that can alleviate depressive symptoms at postpartum. Both stress and family and marital functioning may be moderated and mediated by other factors to predict effect on depressive symptoms. Limitation: predominantly middle class sample |

| [103] | 92 couples in prenatal period, 84 couples in postpartum period. ♂ = 33.72 yr ± 5.13 (23–52); ♀ = 29.95 yr ± 4.86 (20–43) | Cross-sectional. EPDS, MSPSS, RSE, WFCS, MAT. | Prenatal EPDS scores: ♀ = 7.54 ± 4.11, ♂ = 5.33 ± 3.12; Postpartum EPDS score: ♀ = 8.25 ± 3.29, ♂ = 6.52 ± 3.02 | The paternal depression risk was measured as 4.3% in the prenatal period, and it was measured as 7.1% in the postpartum period. The EPDS average score was ↑ in the postpartum period. The results showed that low marital adjustment and work–family conflicts affect paternal depression risk. Also, ♀ depression risk did not affect ♂ depression risk, but↑ depression risk was found for ♂ that did not want the pregnancy |

| [104] | 885 ♂ 926 ♀. ♂ = 32.6 yr (20–51) | Cross-sectional. EPDS (cut off ≥ 12) | 6.3% of ♂ scored 12 or more on EPDS and 9.1% scored zero. 12.0% of ♀ scored 12 or more on EPDS, and 4.8% scored zero. 1.5% of couples reported depressive symptoms in both ♀♂ | The prevalence of depressive symptoms in ♀ seems to be approximately twice that in ♂. Depressive symptoms in one parent were associated with a ↑ risk of depressive symptoms. |

| [105] | 711 couples. T1: 1 mo. postpartum; T2: 6 mo. postpartum; T3: 12 mo. postpartum. | Longitudinal. PSQI, EPDS | At T1, 6.8% of ♂ and 13.4% of ♀ had clinically significant PPD. At T2, 9.7% of ♂ and 13.4% of ♀ had clinically significant PPD. At T3, 9% of ♂ and 13.5% of ♀ had clinically significant PPD. Of those ♂ who reported clinically significant PPD at T1, 26% also had clinically significant PPD at T2 and 50% had clinically significant PPD at T3. Of those ♂ who reported clinically significant PPD at T2, 39% also had clinically significant PPD at T3. | For both partnered ♀ and ♂ and for single ♀, depressive symptoms at 1 month after the birth of a child was associated with poorer sleep at 6 months postpartum, which was in turn associated with more depressive symptoms at both 6 and 12 months postpartum. |

| [106] | 181 couples (362 parents) | Longitudinal. T1: 3 mo. T2: 6 mo. EPDS ♀ ≥ 12 ♂ ≥ 8; STAI > 40; PSI-SF | Mothers reported higher scores on postpartum anxiety, depression, and parenting stress. The scores for all measures for both ♀♂ ↓ from T1 to T2. Parents’ own levels of anxiety and parenting stress and presence of depression in partner seem to directly influence the persistence of both ♀♂ postnatal depression | Both ♀♂ postpartum depression were influenced directly and indirectly by parents’ own anxiety levels and parenting stress as well as by the presence of depression in his/her partner. Although the two models are similar, they differ with respect to the role of parenting stress. The latter was shown to have an effect on maternal postpartum depression at 3 mo. postpartum, whereas it only influences paternal postpartum depression 6 mo. after the child’s birth |