Subjective Assessments of Quality of Life Are Independently Associated with Depressive Symptoms among Older Adults Enrolled in Primary Care in Chile

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

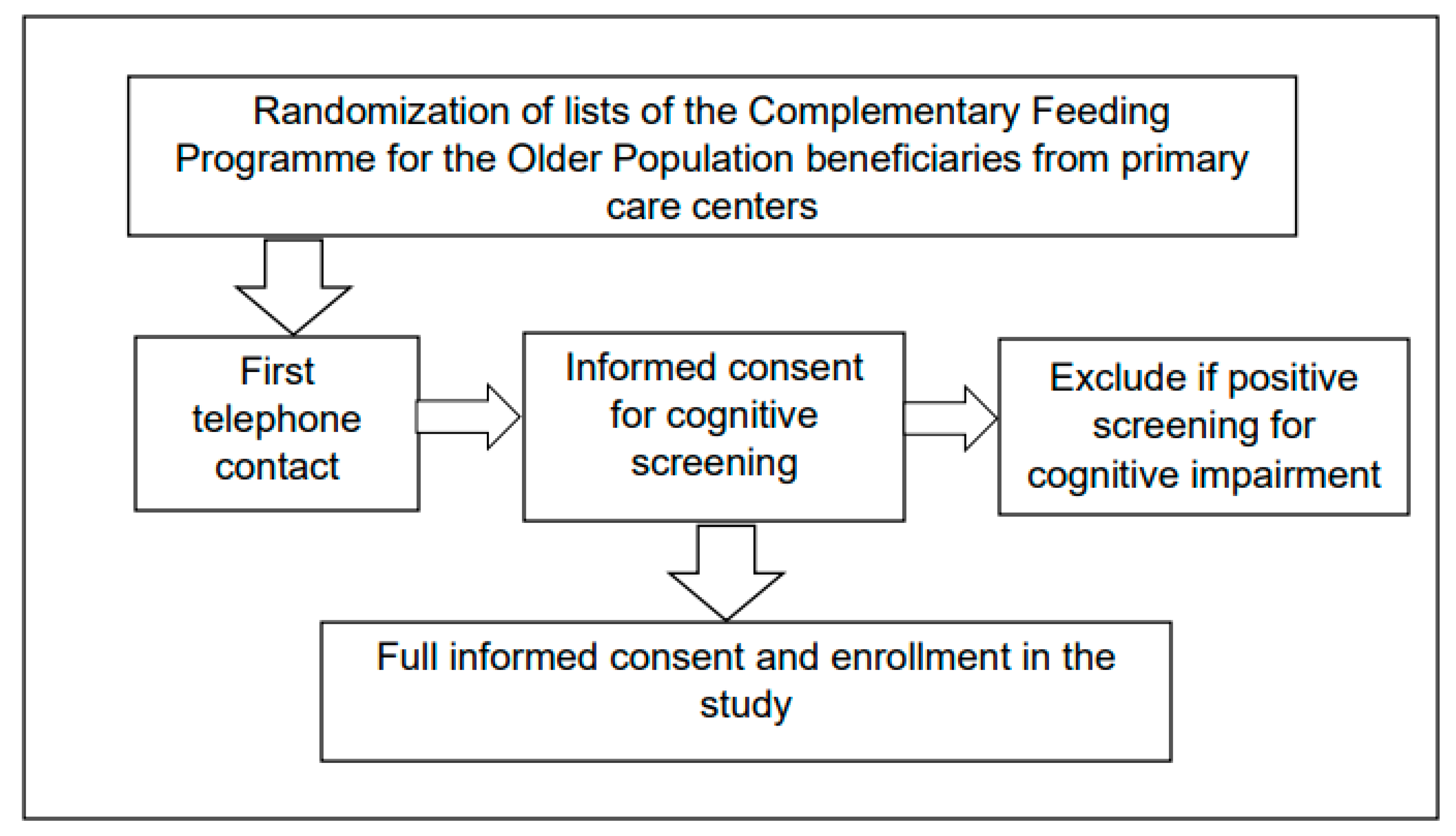

2.1. Participants and Setting

2.2. Measurements and Variables

- -

- To assess self-rated health, the question employed was: “In general, would you say your health is: Excellent, very good, good, fair, poor?”. For analytical purposes, the answers were collapsed into “good” (excellent, very good, and good) and “less than good” (fair and poor).

- -

- Pain was assessed with the question: “Did you have pain in any part of your body, during the last four weeks)?”. A six-point scale was used to answer this question, ranging from 1 (no, no pain) to 6 (yes, very much).

- -

- Self-perceived age was assessed with the question: “Some people of your age feel old, some feel middle aged, and some feel young. How do you feel?”. The possible answers were: young, middle-aged, old, and very old. The answers were collapsed into “not old” (young and middle-aged) and “old” (old and very old).

- -

- A general question about quality of life was used: “How would you say is your quality of life in the present?”. This question included the following answers: excellent, very good, good, fair, poor. The answers to this question were collapsed into “good” (excellent, very good, and good) and “less than good” (fair and poor).

- -

- Self-rated memory was assessed with the question: “How do you rate your memory in the present?”. The response categories were: excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor. Two collapsed categories were used in the analysis: “good” (excellent, very good, and good) and “less than good” (fair and poor).

- -

- To assess self-perceived social support, the question employed was: “If you need material support, company, or advice, do you have someone you can turn to?”. The possible answers were “yes” or “no”.

- -

- Self-reported number of chronic diseases, including hypertension, diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, coronary heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, cancer, osteoarthritis, and cataracts.

- -

- Disability was defined as the inability to perform one or more basic activities of daily living, including walking, bathing, getting dressed, eating, using the toilet, and getting in or out of bed.

- -

- The question: “How many medications per day are you taking?” was used to assess the number of medications.

2.3. Analyses

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Participants Description

3.2. Factors Associated with a Positive Screen for Depression

3.3. Factors Associated with Self-Reported Depression Diagnosis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horackova, K.; Kopecek, M.; Machů, V.; Kagstrom, A.; Aarsland, D.; Motlova, L.B.; Cermakova, P. Prevalence of late-life depression and gap in mental health service use across European regions. Eur. Psychiatry 2019, 57, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voros, V.; Martin Gutierrez, D.; Alvarez, F.; Boda-Jorg, A.; Kovacs, A.; Tenyi, T.; Fekete, S.; Osvath, P. The impact of depressive mood and cognitive impairment on quality of life of the elderly. Psychogeriatr. Off. J. Jpn. Psychogeriatr. Soc. 2020, 20, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, A.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Pabst, A.; Luppa, M. Risk factors and protective factors of depression in older people 65+. A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251326. [Google Scholar]

- Palapinyo, S.; Methaneethorn, J.; Leelakanok, N. Association between polypharmacy and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2021, 51, 280–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Hou, R.; Zhang, X.; Xu, H.; Xie, L.; Chandrasekar, E.K.; Ying, M.; Goodman, M. The association of late-life depression with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among community-dwelling older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 2019, 215, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgus, J.; Yang, K.; Ferri, C. The Gender Difference in Depression: Are Elderly Women at Greater Risk for Depression Than Elderly Men? Geriatrics 2017, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, R.A.; Keyes, K.M.; Medina, J.T.; Calvo, E. Sociodemographic inequalities in depression among older adults: Cross-sectional evidence from 18 countries. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, Y.; Shobugawa, Y.; Nozaki, I.; Takagi, D.; Nagamine, Y.; Funato, M.; Chihara, Y.; Shirakura, Y.; Lwin, K.; Zin, P.; et al. Rural–Urban Differences in the Factors Affecting Depressive Symptoms among Older Adults of Two Regions in Myanmar. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivertsen, H.; Bjørkløf, G.; Engedal, K.; Selbæk, G.; Helvik, A. Depression and Quality of Life in Older Persons: A Review. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2015, 40, 311–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, O.; Teixeira, L.; Araújo, L.; Rodríguez-Blázquez, C.; Calderón-Larrañaga, A.; Forjaz, M.J. Anxiety, Depression and Quality of Life in Older Adults: Trajectories of Influence across Age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Guo, C.; Ping, W.; Tan, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zheng, J. A Community-Based Study of Quality of Life and Depression among Older Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Peña, C.; Wagner, F.A.; Sánchez-García, S.; Espinel-Bermúdez, C.; Juárez-Cedillo, T.; Pérez-Zepeda, M.; Arango-Lopera, V.; Franco-Marina, F.; Ramírez-Aldana, R.; Gallo, J.J. Late-life depressive symptoms: Prediction models of change. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 150, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravena, J.M.; Saguez, R.; Lera, L.; Moya, M.O.; Albala, C. Factors related to depressive symptoms and self-reported diagnosis of depression in community-dwelling older Chileans: A national cross-sectional analysis. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 35, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, X.; Gajardo, J.; Monsalves, M.J. Gender differences in positive screen for depression and diagnosis among older adults in Chile. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, R.; Vicente, B.; Saldivia, S.; Rioseco, P.; Torres, S. Psychiatric epidemiology of the elderly population in Chile. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Off. J. Am. Assoc. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2008, 16, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, J.; Cova, F.; Saldivia, S.; Bustos, C.; Inostroza, C.; Rincón, P.; Ortiz, C.; Bühring, V. Psychometric Properties of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in Elderly Chilean Primary Care Users. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 555011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, E.M.; Albala, C.; Allen, E.; Dangour, A.D.; Elbourne, D.; Uauy, R. Grandparenting and psychosocial health among older Chileans: A longitudinal analysis. Aging Ment. Health 2012, 16, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, J.; Rojas, G. Integration of mental health into primary care: A Chilean perspective on a global challenge. BJPsych Int. 2016, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, R.; Zitko, P.; Markkula, N. The Impact of Universal Health Care Programmes on Improving “Realized Access” to Care for Depression in Chile. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2018, 45, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Silva, C.A.; Rojas Orellana, P.A.; Marzuca-Nassr, G.N. Criterios de valoración geriátrica integral en adultos mayores con dependencia moderada y severa en Centros de Atención Primaria en Chile [Functional geriatric assessment in primary health care]. Rev. Médica Chile 2015, 143, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, B.; Kohn, R.; Rioseco, P.; Saldivia, S.; Levav, I.; Torres, S. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders in the Chile psychiatric prevalence study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Peralta, L.; Sánchez-Moreno, E. Espiritualidad, religiosidad y síntomas depresivos en personas mayores del norte de Chile [Spirituality, religiosity, and depressive symptomsamong elderly Chilean people in the north of Chile]. Ter. Psicológ. 2020, 38, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, M.; Fernández, M.B.; Alexander, E.; Herrera, M.S. Loneliness in oldhileanean people: Importance of family dysfunction and depression. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2021, 23, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Muñoz, T.; Mascayano, F.; Toso-Salman, J. Collaborative care models to address late-life depression: Lessons for low-and-middle-income countries. Front. Psychiatry 2015, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, H.; Albala, C.; Angel, B.; Lera, L.; Márquez, C. Cognitive performance and its association with plasma levels of vitamin D in Chilean older people. Gerontol. 2014, 54, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, X.; Sánchez, H.; Huerta, M.; Albala, C.; Márquez, C. Social Representations of Older Adults Among Chilean Elders of Three Cities with Different Historical and Sociodemographic Background. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2016, 31, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, L.P.; Albala, B.C.; Klaasen, P.G. Validación de un test de tamizaje para el diagnóstico de demencia asociada a edad, en Chile [Validation of a screening test for age associated cognitive impairment, in Chile]. Rev. Médica Chile 2004, 132, 467–478. [Google Scholar]

- Ríos, M. Desigualdad Regional en Chile: Ingresos, Salud y Educación en Perspectiva Territorial (Regional Inequality in Chile: Income, Health, and Education in Territorial Perspective); PNUD: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pocklington, C.; Gilbody, S.; Manea, L.; McMillan, D. The diagnostic accuracy of brief versions of the Geriatric Depression Scale: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016, 31, 837–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, L.; Zweifach, M.; Oishi, S.; Tang, L.; Unützer, J. Gender disparities in the treatment of late-life depression: Qualitative and quantitative findings from the IMPACT trial. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Off. J. Am. Assoc. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 14, 884–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Rao, S.; Vaze, A. Do primary care physicians have particular difficulty identifying late-life depression? A meta-analysis stratified by age. Psychother. Psychosom. 2010, 79, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Flores Águila, J.; Toffoletto, M.C. La funcionalidad y el acceso a prestaciones de salud de personas mayores en Chile [Functionality and access to health benefits for the elderly in Chile]. Gerokomos 2019, 30, 161–171. [Google Scholar]

- Aravena, J.; Gajardo, J.; Saguez, R. Salud mental de hombres mayores en Chile: Una realidad por priorizar [Mental health in older men in Chile: A reality to be prioritized]. Pan Am. J. Public Health 2018, 42, e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos Dintrans, P. Health Systems, Aging, and Inequity: An Example from Chile. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thumala, D.; Kennedy, B.K.; Calvo, E.; Gonzalez-Billault, C.; Zitko, P.; Lillo, P.; Villagra, R.; Ibáñez, A.; Assar, R.; Andrade, M.; et al. Health Systems & Reform Aging and Health Policies in Chile: New Agendas for Research Aging and Health Policies in Chile: New Agendas for Research. Health Syst. Reform 2017, 3, 253–260. [Google Scholar]

- Parcesepe, A.M.; Cabassa, L.J. Public Stigma of Mental Illness in the United States: A Systematic Literature Review. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2013, 40, 384–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascayano, F.; Tapia, T.; Schilling, S.; Alvarado, R.; Tapia, E.; Lips, W.; Yang, L.H. Stigma toward mental illness in Latin America and the Caribbean: A systematic review. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2016, 38, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapag, J.C.; Sena, B.F.; Bustamante, I.V.; Bobbili, S.J.; Velasco, P.R.; Mascayano, F.; Alvarado, R.; Khenti, A. Stigma towards mental illness and substance use issues in primary health care: Challenges and opportunities for Latin America. Glob. Public Health 2018, 13, 1468–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, K.O.; McKinnon, S.A.; Roker, R.; Ward, C.J.; Brown, C. Mitigating the stigma of mental illness among older adults living with depression: The benefit of contact with a peer educator. Stigma Health 2018, 3, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, K.O.; Copeland, V.C.; Grote, N.K.; Koeske, G.; Rosen, D.; Reynolds, C.F.; Brown, C. Mental health treatment seeking among older adults with depression: The impact of stigma and race. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Off. J. Am. Assoc. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 18, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliffe, J.L.; Ogrodniczuk, J.S.; Gordon, S.J.; Creighton, G.; Kelly, M.T.; Black, N.; Mackenzie, C. Stigma in Male Depression and Suicide: A Canadian Sex Comparison Study. Community Ment. Health J. 2016, 52, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.H.; Kwak, M.J. Performance of the Geriatric Depression Scale-15 with Older Adults Aged over 65 Years: An Updated Review 2000–2019. Clin. Gerontol. 2021, 44, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, M.V.; Diniz, M.F.; Nascimento, K.K.; Pereira, K.S.; Dias, N.S.; Malloy-Diniz, L.F.; Diniz, B.S. Accuracy of three depression screening scales to diagnose major depressive episodes in older adults without neurocognitive disorders. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2016, 38, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hoyl, M.T.; Valenzuela, A.E.; Marín, L.P.P. Depresión en el adulto mayor: Evaluación preliminar de la efectividad, como instrumento de tamizaje, de la versión de 5 ítems de la Escala de Depresión Geriátrica [Preliminary report on the effectiveness of the 5-item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale for depression screening in a Chilean community-dwelling elderly population]. Rev. Médica Chile 2000, 128, 1199–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Mukku, S.S.R.; Dahale, A.B.; Muniswamy, N.R.; Muliyala, K.P.; Sivakumar, P.T.; Varghese, M. Geriatric Depression and Cognitive Impairment-an Update. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2021, 43, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (n = 796) | Men (n = 309) | Women (n = 487) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age % | 0.750 | |||

| 70–74 | 38.61 | 39.87 | 37.82 | |

| 75–79 | 31.66 | 30.23 | 32.56 | |

| 80–84 | 19.18 | 20.27 | 18.49 | |

| 85+ | 10.55 | 9.63 | 11.13 | |

| City % | 0.127 | |||

| North | 23.55 | 26.91 | 21.43 | |

| Center | 39.64 | 35.88 | 42.02 | |

| South | 37.21 | 36.55 | 37.2 | |

| Years of education % | 0.182 | |||

| 0 | 5.55 | 4.01 | 6.51 | |

| <8 | 57.42 | 54.85 | 54.85 | |

| 8–11 | 24.52 | 27.42 | 27.42 | |

| 12+ | 12.52 | 13.71 | 13.71 | |

| Marital status % | <0.001 | |||

| Married | 59.02 | 78.74 | 46.53 | |

| Single | 7.09 | 2.66 | 9.89 | |

| Divorced | 5.03 | 3.65 | 5.89 | |

| Widowed | 28.87 | 14.95 | 37.68 | |

| Number of chronic diseases % | 0.137 | |||

| 0 | 5.92 | 6.98 | 5.25 | |

| 1–2 | 53.67 | 56.81 | 51.68 | |

| 3+ | 40.41 | 36.21 | 43.07 | |

| Disability % | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 9.56 | 4.33 | 12.87 | |

| Number of medications | 0.003 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 4.12 (2.18) | 3.83 (2.21) | 4.31 (2.15) | |

| Self-rated health % | <0.001 | |||

| Good | 53.09 | 63.12 | 46.74 | |

| Less than good | 46.91 | 36.88 | 53.26 | |

| Pain (1–6 scale) | <0.001 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.42 (1.59) | 3.01 (1.55) | 3.69 (1.55) | |

| Self-perceived age % | 0.585 | |||

| Not old | 81.03 | 82.00 | 80.42 | |

| Old | 18.97 | 18.00 | 18.97 | |

| Self-perceived memory % | 0.772 | |||

| Good | 47.16 | 46.51 | 47.58 | |

| Less than good | 52.84 | 53.49 | 52.42 | |

| Quality of life % | 0.347 | |||

| Good | 67.65 | 65.67 | 68.91 | |

| Less than good | 32.35 | 34.33 | 31.09 | |

| Self-perceived social support % | 0.503 | |||

| Yes | 87.98 | 87.00 | 88.61 | |

| No | 12.02 | 13.00 | 11.39 | |

| Positive screen for depression % | 0.003 | |||

| Yes | 22.91 | 17.28 | 26.47 | |

| No | 77.09 | 82.72 | 73.53 | |

| Self-reported diagnosis of depression % | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 17.62 | 6.69 | 24.52 | |

| No | 82.38 | 93.31 | 75.48 |

| Variable (Reference) | OR | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (men) | 1.06 | 0.37–1.67 |

| Age (70–74 years) | ||

| 75–79 | 0.78 | 0.37–1.67 |

| 80–84 | 0.98 | 0.25–3.74 |

| 85+ | 0.97 | 0.11–8.26 |

| Region (center) | ||

| North ** | 0.40 | 0.21–0.77 |

| South | 0.68 | 0.41–1.13 |

| Years of education (12+) | ||

| 0 | 1.10 | 0.37–3.28 |

| 1–7 | 0.88 | 0.42–1.84 |

| 8–11 | 0.88 | 0.40–1.94 |

| Marital status (married) | ||

| Single | 1.12 | 0.46–2.72 |

| Divorced | 1.41 | 0.48–4.10 |

| Widowed | 1.47 | 0.87–2.49 |

| Number of chronic diseases (0) | ||

| 1–2 | 2.44 | 0.53–11.20 |

| 3+ | 4.50 | 0.95–21.33 |

| Disability (no) *** | 4.45 | 2.31–8.54 |

| Number of medications | 1.03 | 0.93–1.15 |

| Self-rated health (good) ** | 2.23 | 1.37–3.64 |

| Level of pain * | 1.19 | 1.02–1.38 |

| Self-perceived age (not old) | 1.01 | 0.89–1.16 |

| Self-perceived memory (good) * | 1.67 | 1.07–2.62 |

| Self-perceived quality of life (good) *** | 2.44 | 1.58–3.76 |

| Self-perceived social support (yes) | 1.80 | 0.99–3.24 |

| Variable (Reference) | OR | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (men) *** | 3.30 | 1.86–5.87 |

| Age (70–74 years) | ||

| 75–79 | 1.51 | 0.69–3.28 |

| 80–84 | 1.00 | 0.24–4.18 |

| 85+ | 0.60 | 0.06–6.04 |

| Region (center) | ||

| North | 1.22 | 0.69–2.17 |

| South | 0.68 | 0.39–1.17 |

| Marital status (married) | ||

| Single | 0.81 | 0.32–2.08 |

| Divorced | 0.88 | 0.30–2.59 |

| Widowed ** | 2.00 | 1.24–3.26 |

| Number of chronic diseases (0) | ||

| 1–2 | 0.56 | 0.17–1.84 |

| 3+ | 0.64 | 0.19–2.20 |

| Disability (no) * | 2.11 | 1.10–4.10 |

| Number of medications *** | 1.23 | 1.10–1.38 |

| Self-rated health (good) | 1.31 | 0.79–2.17 |

| Level of pain ** | 1.27 | 1.08–1.50 |

| Self-perceived age (not old) | 0.97 | 0.85–1.11 |

| Self-perceived quality of life (good) | 1.55 | 0.98–2.45 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moreno, X.; Sánchez, H.; Huerta, M.; Cea, X.; Márquez, C.; Albala, C. Subjective Assessments of Quality of Life Are Independently Associated with Depressive Symptoms among Older Adults Enrolled in Primary Care in Chile. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12071063

Moreno X, Sánchez H, Huerta M, Cea X, Márquez C, Albala C. Subjective Assessments of Quality of Life Are Independently Associated with Depressive Symptoms among Older Adults Enrolled in Primary Care in Chile. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2022; 12(7):1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12071063

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreno, Ximena, Hugo Sánchez, Martín Huerta, Ximena Cea, Carlos Márquez, and Cecilia Albala. 2022. "Subjective Assessments of Quality of Life Are Independently Associated with Depressive Symptoms among Older Adults Enrolled in Primary Care in Chile" Journal of Personalized Medicine 12, no. 7: 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12071063

APA StyleMoreno, X., Sánchez, H., Huerta, M., Cea, X., Márquez, C., & Albala, C. (2022). Subjective Assessments of Quality of Life Are Independently Associated with Depressive Symptoms among Older Adults Enrolled in Primary Care in Chile. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 12(7), 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12071063