The Comparison of Predicting Factors and Outcomes of MINOCA and STEMI Patients in the 5-Year Follow-Up

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

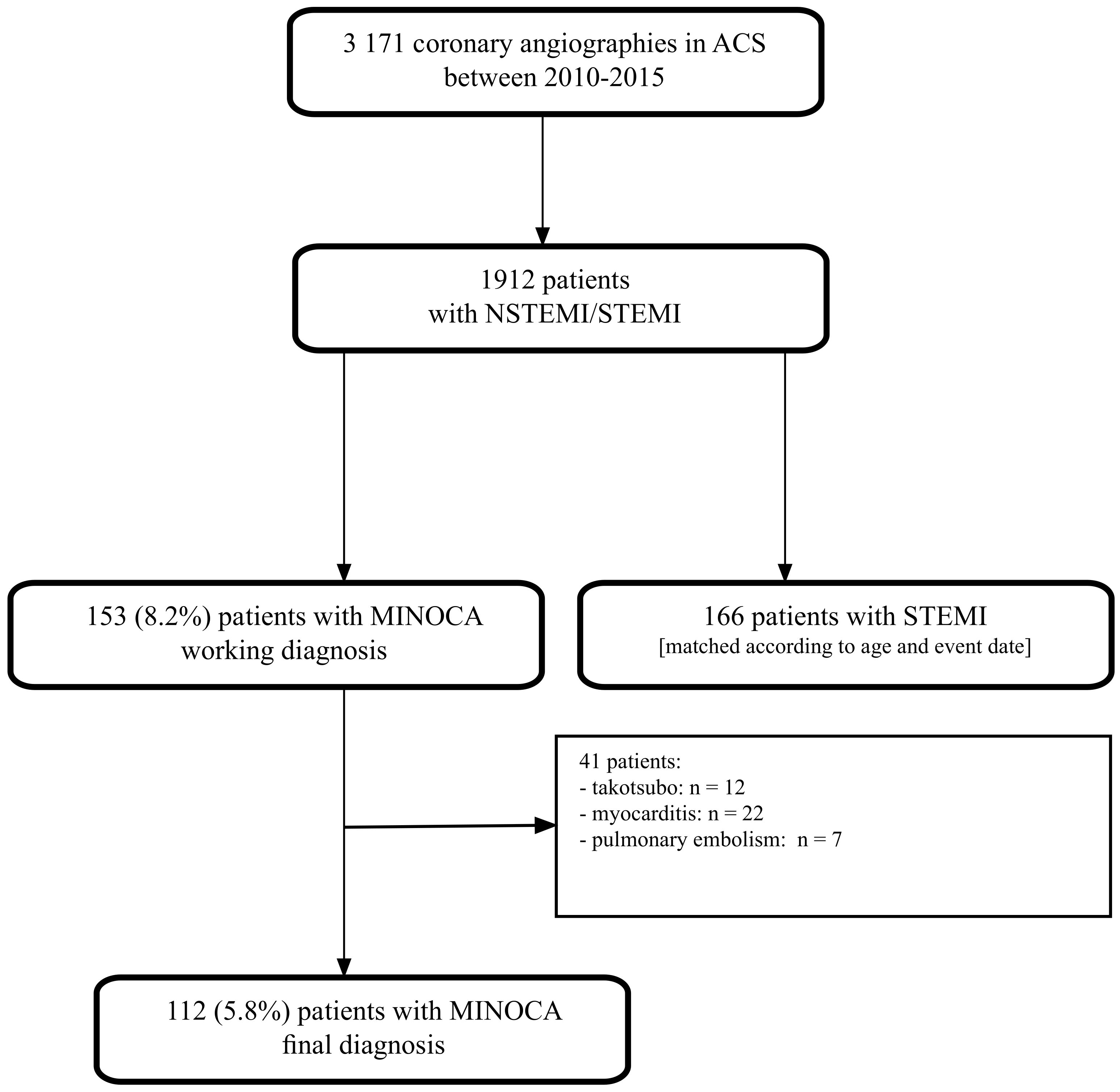

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Study Endpoints

2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Management at Discharge

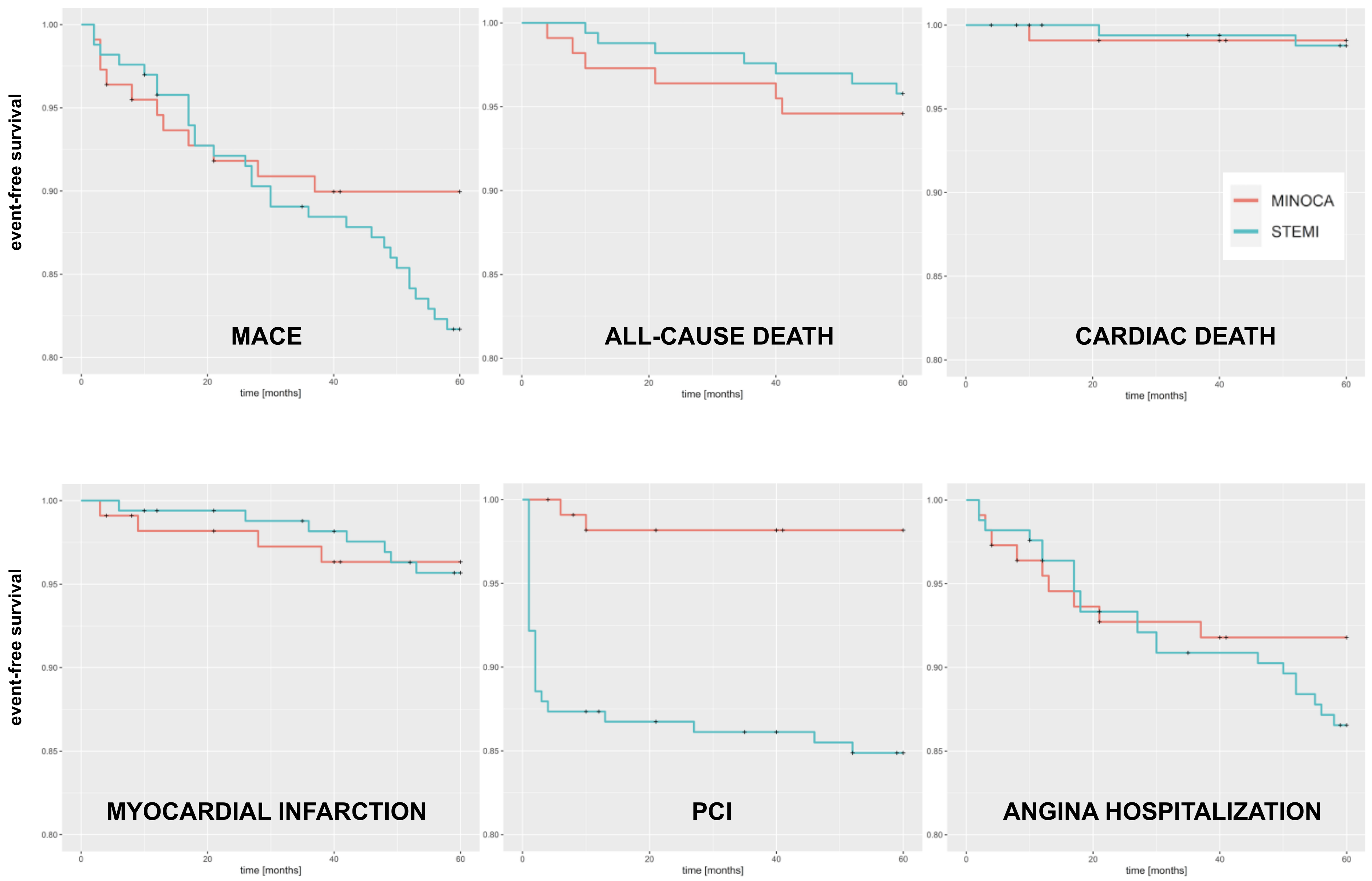

3.3. Outcomes at 5 Years

3.4. Predictor Factors for MACE at 5-Year Follow-Up

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bil, J.; Pietraszek, N.; Gil, R.J.; Gromadzinski, L.; Onichimowski, D.; Jalali, R.; Kern, A. Complete Blood Count-Derived Indices as Prognostic Factors of 5-Year Outcomes in Patients with Confirmed Coronary Microvascular Spasm. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 933374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casolo, G.; Gabrielli, D.; Colivicchi, F.; Murrone, A.; Grosseto, D.; Gulizia, M.M.; Di Fusco, S.; Domenicucci, S.; Scotto di Uccio, F.; Di Tano, G.; et al. ANMCO Position Paper: Prognostic and therapeutic relevance of non-obstructive coronary atherosclerosis. Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 2021, 23 (Suppl. C), C164–C175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bil, J.; Mozenska, O.; Segiet-Swiecicka, A.; Gil, R.J. Revisiting the use of the provocative acetylcholine test in patients with chest pain and nonobstructive coronary arteries: A five-year follow-up of the AChPOL registry, with special focus on patients with MINOCA. Transl. Res. 2021, 231, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atri, D.; Siddiqi, H.K.; Lang, J.P.; Nauffal, V.; Morrow, D.A.; Bohula, E.A. COVID-19 for the Cardiologist: Basic Virology, Epidemiology, Cardiac Manifestations, and Potential Therapeutic Strategies. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2020, 5, 518–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesada, O.; Van Hon, L.; Yildiz, M.; Madan, M.; Sanina, C.; Davidson, L.; Htun, W.W.; Saw, J.; Garcia, S.; Dehghani, P.; et al. Sex Differences in Clinical Characteristics, Management Strategies, and Outcomes of STEMI with COVID-19: NACMI Registry. J. Soc. Cardiovasc. Angiogr. Interv. 2022, 1, 100360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, G.; Bricoli, S.; Ardissino, M.; Maglietta, G.; Nelson, A.; Malagoli Tagliazucchi, G.; Disisto, C.; Celli, P.; Ferrario, M.; Canosi, U.; et al. Long-term outcomes of early-onset myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary artery disease (MINOCA). Int. J. Cardiol. 2022, 354, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; He, Y.; Cheang, I.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Kong, X. Clinical characteristics and outcome in patients with ST-segment and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction without obstructive coronary artery: An observation study from Chinese population. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2022, 22, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasupathy, S.; Lindahl, B.; Litwin, P.; Tavella, R.; Williams, M.J.A.; Air, T.; Zeitz, C.; Smilowitz, N.R.; Reynolds, H.R.; Eggers, K.M.; et al. Survival in Patients with Suspected Myocardial Infarction With Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis from the MINOCA Global Collaboration. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2021, 14, e007880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racz, A.O.; Racz, I.; Szabo, G.T.; Uveges, A.; Koszegi, Z.; Penczu, B.; Kolozsvari, R. The Effects of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention on the Flow in Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients-Geometry in Focus. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, K.; Groth, N.; Mullvain, R.; Renier, C.; Oluleye, O.; Benziger, C. Prevalence, Clinical Factors, and Outcomes Associated With Myocardial Infarction with Nonobstructive Coronary Artery. Crit. Pathw. Cardiol. 2021, 20, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabaldon-Perez, A.; Bonanad, C.; Garcia-Blas, S.; Marcos-Garces, V.; D’Gregorio, J.G.; Fernandez-Cisnal, A.; Valero, E.; Minana, G.; Merenciano-Gonzalez, H.; Mollar, A.; et al. Clinical Predictors and Prognosis of Myocardial Infarction with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries (MINOCA) without ST-Segment Elevation in Older Adults. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smilowitz, N.R.; Mahajan, A.M.; Roe, M.T.; Hellkamp, A.S.; Chiswell, K.; Gulati, M.; Reynolds, H.R. Mortality of Myocardial Infarction by Sex, Age, and Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease Status in the ACTION Registry-GWTG (Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network Registry-Get with the Guidelines). Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2017, 10, e003443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collet, J.P.; Thiele, H.; Barbato, E.; Barthelemy, O.; Bauersachs, J.; Bhatt, D.L.; Dendale, P.; Dorobantu, M.; Edvardsen, T.; Folliguet, T.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 1289–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bil, J.; Pietraszek, N.; Pawlowski, T.; Gil, R.J. Advances in Mechanisms and Treatment Options of MINOCA Caused by Vasospasm or Microcirculation Dysfunction. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossard, M.; Gao, P.; Boden, W.; Steg, G.; Tanguay, J.F.; Joyner, C.; Granger, C.B.; Kastrati, A.; Faxon, D.; Budaj, A.; et al. Antiplatelet therapy in patients with myocardial infarction without obstructive coronary artery disease. Heart 2021, 107, 1739–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasior, P.; Desperak, A.; Gierlotka, M.; Milewski, K.; Wita, K.; Kalarus, Z.; Fluder, J.; Kazmierski, M.; Buszman, P.E.; Gasior, M.; et al. Clinical Characteristics, Treatments, and Outcomes of Patients with Myocardial Infarction with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries (MINOCA): Results from a Multicenter National Registry. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bil, J.; Kern, A.; Bujak, K.; Gierlotka, M.; Legutko, J.; Gasior, M.; Wanha, W.; Gromadzinski, L.; Gil, R.J. Clinical characteristics and 12-month outcomes in MINOCA patients before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2023, 16405, ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gok, G.; Coner, A.; Cinar, T.; Kilic, S.; Yenercag, M.; Oz, A.; Ekmekci, C.; Ozluk, O.; Zoghi, M.; Ergene, A.O.; et al. Evaluation of demographic and clinical characteristics of female patients presenting with MINOCA and differences between male patients: A subgroup analysis of MINOCA-TR registry. Turk Kardiyol. Dern. Ars. 2022, 50, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bil, J.; Pawlowski, T.; Gil, R.J. Coronary spasm revascularized with a bioresorbable vascular scaffold. Coron. Artery Dis. 2015, 26, 634–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucciarelli, V.; Bianco, F.; Francesco, A.D.; Vitulli, P.; Biasi, A.; Primavera, M.; Belleggia, S.; Ciliberti, G.; Guerra, F.; Seferovic, J.; et al. Characteristics and Prognosis of a Contemporary Cohort with Myocardial Infarction with Non-Obstructed Coronary Arteries (MINOCA) Presenting Different Patterns of Late Gadolinium Enhancements in Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bil, J.; Gil, R.J.; Vassilev, D.; Gromadzinski, L.; Onichimowski, D.; Jalali, R.; Kern, A. Intracoronary ECG monitoring during provocation acetylcholine test in chest pain patients with non-obstructive coronary artery disease: Results from the AChPOL Registry. Kardiol. Pol. 2022, 80, 1256–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bil, J.; Tyczynski, M.; Modzelewski, P.; Gil, R.J. Acetylcholine provocation test with resting full-cycle ratio, coronary flow reserve, and index of microcirculatory resistance give definite answers and improve health-related quality of life. Kardiol. Pol. 2020, 78, 1291–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fluder-Wlodarczyk, J.; Milewski, M.; Roleder-Dylewska, M.; Haberka, M.; Ochala, A.; Wojakowski, W.; Gasior, P. Underlying Causes of Myocardial Infarction with Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries: Optical Coherence Tomography and Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging Pilot Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunadian, V.; Chieffo, A.; Camici, P.G.; Berry, C.; Escaned, J.; Maas, A.; Prescott, E.; Karam, N.; Appelman, Y.; Fraccaro, C.; et al. An EAPCI Expert Consensus Document on Ischaemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries in Collaboration with European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Coronary Pathophysiology & Microcirculation Endorsed by Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 3504–3520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Quesada, O.; Yildiz, M.; Henry, T.D.; Okeson, B.K.; Chambers, J.; Shah, A.; Stanberry, L.; Volpenhein, L.; Aziz, D.; Lantz, R.; et al. Characteristics and Long-term Mortality in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries (STE-MINOCA): A High Risk Cohort. medRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewska-Adamiec, M.; Malyszko, J.; Grodzka, E.; Kuzma, L.; Dobrzycki, S.; Bachorzewska-Gajewska, H. The outcome of patients with myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA) and impaired kidney function: A 3-year observational study. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2021, 53, 2557–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Fan, Y.; Fang, Z.; Liu, N. Long-term outcomes and predictors of patients with ST elevated versus non-ST elevated myocardial infarctions in non-obstructive coronary arteries: A retrospective study in Northern China. PeerJ 2023, 11, e14958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedrychowska, M.; Siudak, Z.; Malinowski, K.P.; Zandecki, L.; Zabojszcz, M.; Kameczura, T.; Mika, P.; Bartus, K.; Wanha, W.; Wojakowski, W.; et al. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries: Score derivation for prediction based on a large national registry. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | MINOCA N = 112 | STEMI N = 166 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Females | 67 (60%) | 43 (26%) | <0.001 |

| Age [years] | 63 ± 14 | 61 ± 11 | 0.2 |

| Body mass index [kg/m2] | 27.9 ± 5.8 | 28.1 ± 4.8 | 0.3 |

| Myocardial infarction type at presentation | |||

| NSTEMI | 94 (83.9%) | - | - |

| STEMI | 18 (16.1%) | 166 (100) | <0.001 |

| Arterial hypertension | 59 (53%) | 69 (42%) | 0.068 |

| Diabetes type 2 | 15 (13%) | 29 (17%) | 0.4 |

| Dyslipidemia | 28 (25%) | 62 (37%) | 0.031 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 0 (0%) | 9 (5.4%) | 0.012 |

| Prior PCI | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.8%) | 0.3 |

| Prior CABG | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.6%) | >0.9 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4 (3.6%) | 9 (5.4%) | 0.5 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 25 (22%) | 9 (5.4%) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 1 (0.9%) | 5 (3.0%) | 0.4 |

| Smoking | 13 (12%) | 27 (16%) | 0.3 |

| Echocardiographic parameters | |||

| LVEDd [mm] | 48.7 ± 6.0 | 51.4 ± 6.4 | <0.0001 |

| IVSd [mm] | 11.1 ± 2.6 | 11.3 ± 2.0 | 0.056 |

| LA [mm] | 39.8 ± 6.4 | 3.96 ± 5.6 | >0.9 |

| LVEF [%] | 59 ± 10 | 54 ± 10 | <0.001 |

| Parameter | MINOCA N = 112 | STEMI N = 166 |

|---|---|---|

| Coronary lesions | ||

| No lesions | 51 (45.5%) | - |

| <30% | 41 (36.6%) | - |

| 30–50% | 20 (17.9%) | - |

| Intravascular imaging use | 5 (4.5%) | 20 (12.1%) |

| Infarct-related artery | ||

| LAD | - | 79 (47.6%) |

| LCx | - | 19 (11.4%) |

| RCA | - | 68 (41.0%) |

| TIMI before PCI | ||

| 0 | - | 142 (85.5%) |

| 1 | - | 20 (12.1%) |

| 2 | - | 4 (2.4%) |

| 3 | - | 0 |

| TIMI post PCI | ||

| 0 | - | 1 (0.6%) |

| 1 | - | 1 (0.6%) |

| 2 | - | 4 (2.4%) |

| 3 | - | 160 (96.4%) |

| Disease advancement | ||

| 1VD | - | 70 (42.2%) |

| 2VD | - | 62 (37.3%) |

| 3VD/LM | - | 34 (20.5%) |

| Stent implanted | ||

| BMS | - | 117 (70.5%) |

| DES | - | 45 (27.1%) |

| No stent | - | 4 (2.4%) |

| Parameter | MINOCA N = 112 | STEMI N = 166 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cells [109/L] | 9.8 ± 4.1 | 11.7 ± 3.8 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin [g/dL] | 13.84 ± 1.47 | 14.55 ± 1.40 | <0.001 |

| Red blood cells [1012/L] | 4.55 ± 0.48 | 4.76 ± 0.47 | 0.002 |

| Platelets [109/L] | 250 ± 80 | 261 ± 72 | 0.13 |

| Glucose [mmol/L] | 7.43 ± 2.48 | 9.08 ± 3.56 | <0.001 |

| HbA1c [%] | 5.91 ± 0.37 | 7.99 ± 2.28 | 0.053 |

| NT-proBNP [pg/mL] | 3747 ± 5149 | 5622 ± 5323 | 0.005 |

| C-reactive protein | 3.5 ± 9.5 | 5.6 ± 7.1 | 0.3 |

| AST [U/L] | 74 ± 128 | 143 ± 144 | 0.092 |

| ALT [U/L] | 41 ± 28 | 54 ± 30 | 0.13 |

| Total cholesterol [mmol/L] | 4.78 ± 1.11 | 5.24 ± 1.13 | 0.004 |

| HDL [mmol/L] | 1.58 ± 0.65 | 1.23 ± 0.35 | <0.001 |

| LDL [mmol/L] | 2.59 ± 1.04 | 3.22 ± 1.00 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides [mmol/L] | 1.37 ± 0.60 | 1.72 ± 0.98 | 0.002 |

| Creatine [µmol/l] | 86 ± 32 | 91 ± 19 | <0.001 |

| TSH [µU/mL] | 1.57 ± 1.42 | 1.50 ± 1.61 | 0.4 |

| Uric acid [µmol/L] | 406 ± 111 | 414 ± 98 | 0.6 |

| Maximal troponin T [ng/mL] | |||

| 0–500 | 67 (59.8%) | 16 (9.6%) | <0.001 |

| 501–2500 | 39 (34.8%) | 45 (27.2%) | |

| 2501–10,000 | 6 (5.4%) | 91 (54.8%) | |

| 10,000+ | 0 | 14 (8.4%) | |

| Parameter | MINOCA N = 112 | STEMI N = 166 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASA | 105 (95%) | 166 (100%) | 0.004 |

| Clopidogrel | 81 (73%) | 166 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Beta-blocker | 88 (79%) | 150 (90%) | 0.009 |

| Ca-blocker | 28 (25%) | 16 (9.6%) | <0.001 |

| ACE inhibitor | 81 (73%) | 155 (93%) | <0.001 |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | 5 (4.5%) | 2 (1.2%) | 0.12 |

| Diuretic | 25 (23%) | 19 (11%) | 0.013 |

| Trimetazidine | 2 (1.8%) | 4 (2.4%) | >0.9 |

| Nitrates | 61 (55%) | 127 (77%) | <0.001 |

| Vitamin K antagonist | 13 (12%) | 4 (2.4%) | 0.002 |

| Novel oral anticoagulant | 4 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0.025 |

| Statin | 101 (91%) | 165 (99%) | <0.001 |

| Parameter | MINOCA N = 112 | STEMI N = 166 | HR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause death | 6 (5.4%) | 7 (4.2%) | 0.77 | 0.26–2.29 | 0.6 |

| Cardiac death | 1 (0.9%) | 2 (1.2%) | 1.31 | 0.12–14.5 | 0.8 |

| Myocardial infarction | 4 (3.6%) | 7 (4.2%) | 1.15 | 0.34–3.92 | 0.8 |

| Percutaneous intervention | 2 (1.8%) | 25 (15.1%) | 9.0 | 2.13–38.0 | 0.003 |

| Hospitalization due to angina | 9 (8.1%) | 22 (13.3%) | 1.62 | 0.75–3.53 | 0.2 |

| MACE | 13 (11.6%) | 31 (18.7%) | 1.82 | 0.91–3.63 | 0.09 |

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | — | — | ||||

| Male | 0.55 | 0.15–2.07 | 0.375 | |||

| Age | 1.01 | 0.97–1.05 | 0.762 | |||

| Body mass index | 0.95 | 0.84–1.08 | 0.429 | |||

| Coronary arteries lesions | ||||||

| No lesions | — | — | ||||

| <30% | 0.78 | 0.19–3.27 | 0.735 | |||

| 30–50% | 1.27 | 0.25–6.53 | 0.778 | |||

| Final diagnosis | ||||||

| STEMI | — | — | ||||

| NSTEMI | 0.87 | 0.19–4.04 | 0.862 | |||

| Arterial hypertension | 2.52 | 0.67–9.49 | 0.173 | 2.90 | 0.76–11.0 | 0.118 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.64 | 0.14–2.94 | 0.562 | |||

| Diabetes | 2.38 | 0.63–8.98 | 0.201 | |||

| Smoking | 0.70 | 0.09–5.50 | 0.737 | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.35 | 0.36–5.09 | 0.658 | |||

| NT-proBNP | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.397 | |||

| LDL | 0.68 | 0.38–1.22 | 0.194 | |||

| Creatine | 1.00 | 0.99–1.02 | 0.664 | |||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 0.97 | 0.92–1.02 | 0.239 | 0.97 | 0.92–1.02 | 0.221 |

| Clopidogrel | 0.57 | 0.17–1.96 | 0.374 | |||

| Beta-blocker | 0.43 | 0.12–1.46 | 0.173 | 0.33 | 0.10–1.15 | 0.082 |

| Ca blocker | 1.78 | 0.52–6.07 | 0.359 | |||

| ACE inhibitor | 1.00 | 0.27–3.78 | 0.997 | |||

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | 2.21 | 0.28–17.3 | 0.450 | |||

| Statin | 0.95 | 0.12–7.44 | 0.963 | |||

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | - | - | ||||

| Male | 2.38 | 0.83–6.82 | 0.106 | 2.87 | 0.98–8.46 | 0.056 |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.96–1.03 | 0.633 | |||

| Body mass index | 0.98 | 0.90–1.06 | 0.602 | |||

| IRA location | ||||||

| LAD | - | - | - | - | - | |

| LCx | 2.19 | 0.77–6.21 | 0.142 | 2.20 | 0.74–6.58 | 0.156 |

| RCA | 1.29 | 0.59–2.82 | 0.529 | 1.35 | 0.58–3.16 | 0.490 |

| Disease advancement | ||||||

| 1VD | - | - | ||||

| 2VD | 1.51 | 0.66–3.43 | 0.331 | |||

| 3VD/LM | 1.53 | 0.58–4.03 | 0.385 | |||

| Stent type | ||||||

| BMS | - | - | ||||

| DES | 0.60 | 0.25–1.47 | 0.264 | 0.51 | 0.19–1.35 | 0.174 |

| Arterial hypertension | 0.81 | 0.39–1.71 | 0.583 | |||

| Dyslipidemia | 1.31 | 0.64–2.69 | 0.467 | |||

| Diabetes | 0.98 | 0.38–2.57 | 0.973 | |||

| Smoking | 0.76 | 0.26–2.17 | 0.606 | |||

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.50 | 0.36–6.32 | 0.577 | |||

| Peripheral artery disease | 1.30 | 0.18–9.55 | 0.797 | |||

| Prior myocardial infarction | 0.67 | 0.09–4.94 | 0.697 | |||

| NTproBNP | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.852 | |||

| LDL | 1.29 | 0.89–1.88 | 0.181 | 1.22 | 0.85–1.77 | 0.281 |

| Creatine | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 | 0.803 | |||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 1.02 | 0.98–1.06 | 0.431 | |||

| Beta-blocker | 3.28 | 0.45–24.1 | 0.243 | 3.78 | 0.50–28.4 | 0.197 |

| Ca blocker | 0.66 | 0.16–2.77 | 0.569 | |||

| ACE inhibitor | 2.10 | 0.29–15.4 | 0.466 | |||

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | 4.88 | 0.66–35.9 | 0.119 | 9.35 | 1.03–84.6 | 0.047 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buller, P.; Kern, A.; Tyczyński, M.; Rosiak, W.; Figatowski, W.; Gil, R.J.; Bil, J. The Comparison of Predicting Factors and Outcomes of MINOCA and STEMI Patients in the 5-Year Follow-Up. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 856. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13050856

Buller P, Kern A, Tyczyński M, Rosiak W, Figatowski W, Gil RJ, Bil J. The Comparison of Predicting Factors and Outcomes of MINOCA and STEMI Patients in the 5-Year Follow-Up. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2023; 13(5):856. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13050856

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuller, Patryk, Adam Kern, Maciej Tyczyński, Wojciech Rosiak, Włodzimierz Figatowski, Robert J. Gil, and Jacek Bil. 2023. "The Comparison of Predicting Factors and Outcomes of MINOCA and STEMI Patients in the 5-Year Follow-Up" Journal of Personalized Medicine 13, no. 5: 856. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13050856

APA StyleBuller, P., Kern, A., Tyczyński, M., Rosiak, W., Figatowski, W., Gil, R. J., & Bil, J. (2023). The Comparison of Predicting Factors and Outcomes of MINOCA and STEMI Patients in the 5-Year Follow-Up. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 13(5), 856. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13050856