Daily Duration of Compression Treatment in Chronic Venous Disease Patients: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

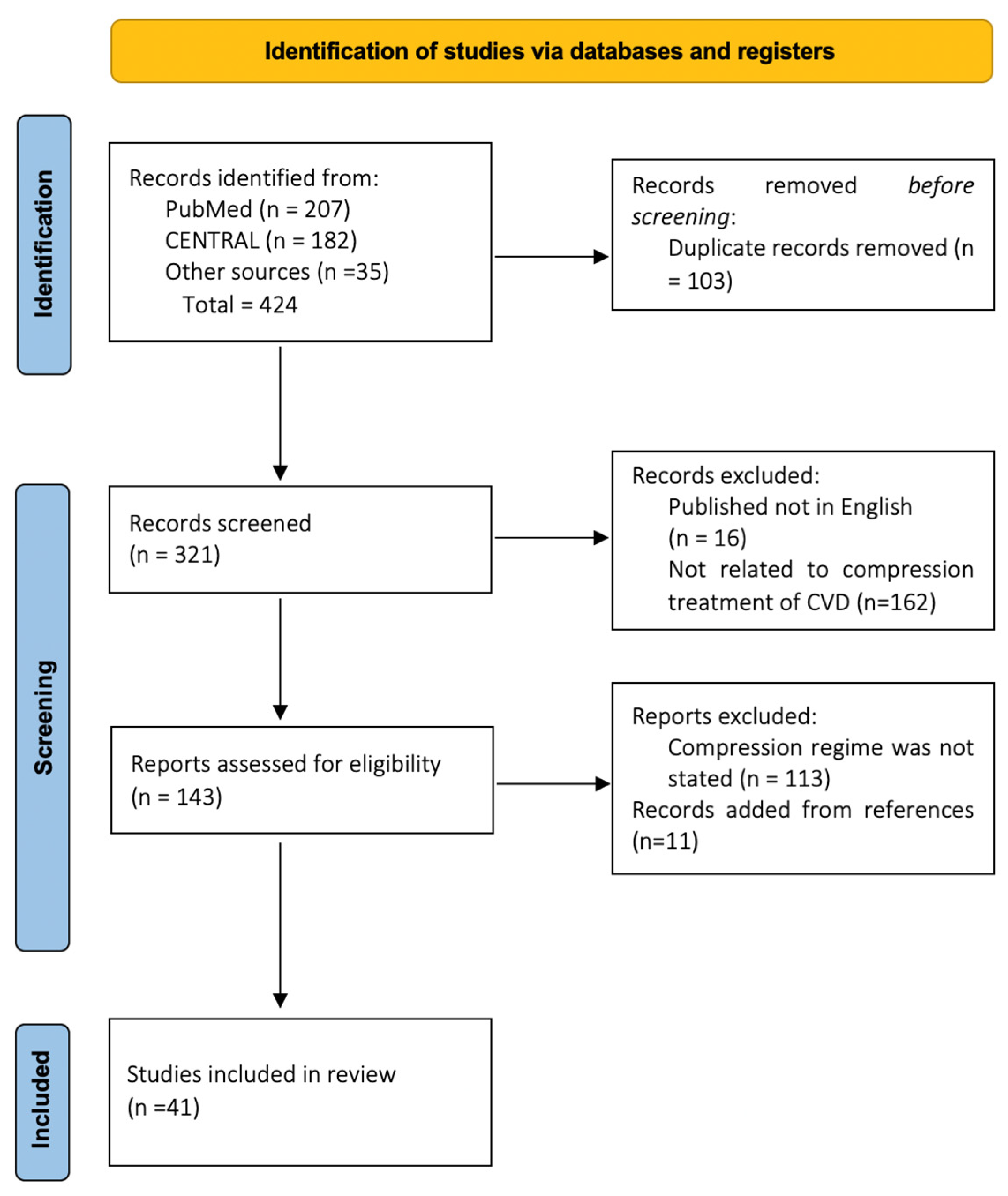

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Included Studies

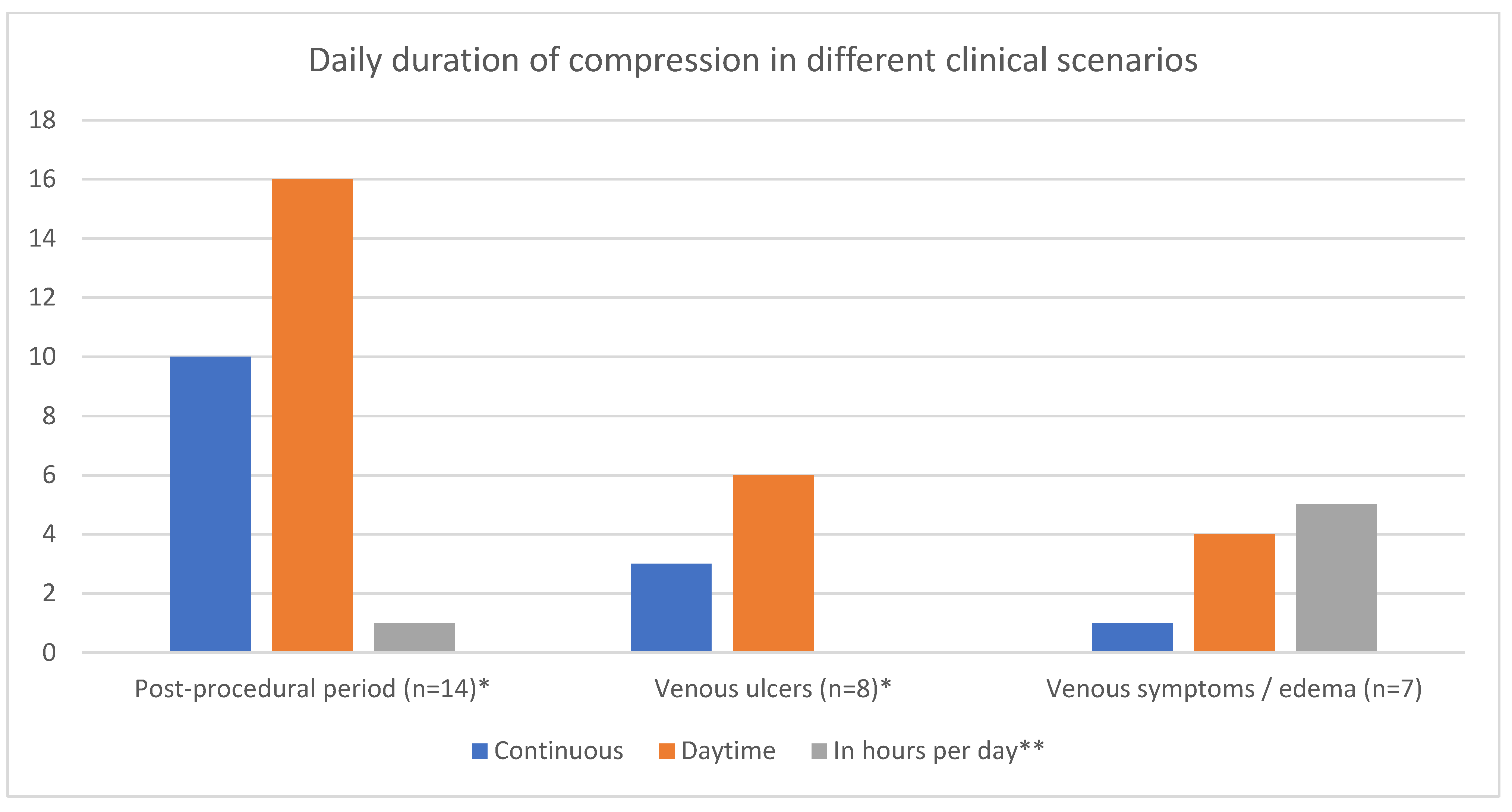

3.3. Daily Duration of Compression after Invasive Procedures

3.4. Daily Duration of Compression for Venous Ulcers’ Treatment

3.5. Daily Duration of Compression in Patients with Venous Symptoms/Edema

3.6. Risk of Bias

3.7. Meta-Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carpentier, P.H.; Maricq, H.R.; Biro, C.; Ponçot-Makinen, C.O.; Franco, A. Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical patterns of chronic venous disorders of lower limbs: A population-based study in France. J. Vasc. Surg. 2004, 40, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.J.; Fowkes, F.G.; Ruckley, C.V.; Lee, A.J. Prevalence of varicose veins and chronic venous insufficiency in men and women in the general population: Edinburgh Vein Study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1999, 53, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurins, U.; Hoffmann, B.H.; Lösch, C.; Jöckel, K.H.; Rabe, E.; Pannier, F. Distribution and prevalence of reflux in the superficial and deep venous system in the general population-results from the Bonn Vein Study, Germany. J. Vasc. Surg. 2008, 48, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seliverstov, E.I.; Avak’yants, I.P.; Nikishkov, A.S.; Zolotukhin, I.A. Epidemiology of Chronic Venous Disease. Flebologiia 2016, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvall, K.A.L.; Bate, G.R.; Adam, D.J.; Bradbury, A.W. Generic health-related quality of life is significantly worse in varicose vein patients with lower limb symptoms independent of CEAP clinical grade. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2012, 44, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beebe-Dimmer, J.L.; Pfeifer, J.R.; Engle, J.S.; Schottenfeld, D. The epidemiology of chronic venous insufficiency and varicose veins. Ann. Epidemiol. 2005, 15, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amsler, F.; Blättler, W. Compression Therapy for Occupational Leg Symptoms and Chronic Venous Disorders—A Meta-analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2008, 35, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benigni, J.P.; Sadoun, S.; Allaert, F.A.; Vin, F. Efficacy of Class 1 elastic compression stockings in the early stages of chronic venous disease. A comparative study. Int. Angiol. 2003, 22, 383–392. [Google Scholar]

- Hirai, M.; Iwata, H.; Hayakawa, N. Effect of elastic compression stockings in patients with varicose veins and healthy controls measured by strain gauge plethysmography. Ski. Res. Technol. 2002, 8, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partsch, H.; Winiger, J.; Lun, B.; Goldman, M. Compression stockings reduce occupational leg swelling. Dermatol. Surg. 2004, 30, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bootun, R.; Belramman, A.; Bolton-Saghdaoui, L.; Lane, T.R.A.; Riga, C.; Davies, A.H. Randomized Controlled Trial of Compression After Endovenous Thermal Ablation of Varicose Veins (COMETA Trial). Ann. Surg. 2021, 273, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lurie, F.; Lal, B.K.; Antignani, P.L.; Blebea, J.; Bush, R.; Caprini, J.; Davies, A.; Forrestal, M.; Jacobowitz, G.; Kalodiki, E.; et al. Compression therapy after invasive treatment of superficial veins of the lower extremities: Clinical practice guidelines of the American Venous Forum, Society for Vascular Surgery, American College of Phlebology, Society for Vascular Medicine, and Interna. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2019, 7, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, J.H.; Chen, S.Y.; Chen, Y.T.; Hsieh, C.H.; Huang, T.W.; Tam, K.W. Optimal duration of compression stocking therapy following endovenous thermal ablation for great saphenous vein insufficiency: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2019, 65, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elderman, J.H.; Krasznai, A.G.; Voogd, A.C.; Hulsewé, K.W.E.; Sikkink, C.J.J.M. Role of compression stockings after endovenous laser therapy for primary varicosis. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2014, 2, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maeseneer, M.G.; Kakkos, S.K.; Aherne, T.; Baekgaard, N.; Black, S.; Blomgren, L.; Giannoukas, A.; Gohel, M.; de Graaf, R.; Hamel-Desnos, C.; et al. Editor’s Choice–European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2022 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Chronic Venous Disease of the Lower Limbs. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2022, 63, 184–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partsch, H. Evidence based Compression-Therapy—An Initiative of the International Union of Phlebology (IUP). VASA 2004, 34 (Suppl. 63), 3–39. Available online: http://www.tagungsmanagement.org/icc/images/stories/PDF/vasa%20suppl%20ebm.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Gloviczki, P.; Comerota, A.J.; Dalsing, M.C.; Eklof, B.G.; Gillespie, D.L.; Gloviczki, M.L.; Lohr, J.M.; McLafferty, R.B.; Meissner, M.H.; Murad, M.H.; et al. The care of patients with varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases: Clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011, 53 (Suppl. 5), 2S–48S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankam, H.K.N.; Lim, C.S.; Fiorentino, F.; Davies, A.H.; Gohel, M.S. A Summation Analysis of Compliance and Complications of Compression Hosiery for Patients with Chronic Venous Disease or Post-thrombotic Syndrome. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2018, 55, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich-Schupke, S.; Murmann, F.; Altmeyer, P.; Stücker, M. Quality of Life and Patients’ View of Compression Therapy. Int. Angiol. A J. Int. Union Angiol. 2009, 28, 385–393. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19935593 (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Gong, J.M.; Du, J.S.; Han, D.M.; Wang, X.Y.; Qi, S.L. Reasons for patient non-compliance with compression stockings as a treatment for varicose veins in the lower limbs: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, S.; Hollis, K.; Neglen, P. Use of Compression Stockings in Chronic Venous Disease: Patient Compliance and Efficacy. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2007, 21, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziaja, D.; Kocełak, P.; Chudek, J.; Ziaja, K. Compliance with compression stockings in patients with chronic venous disorders. Phlebol. J. Venous Dis. 2011, 26, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ctoyko, Y.M.; Kirienko, A.I.; Zatevakhin, I.I. Russian Clinical Guidelines for the Diagnostics and Treatment of Chronic Venous Diseases. Flebologiia 2018, 12, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, K.; Wang, R.; Qin, J.; Yang, X.; Yin, M.; Liu, X.; Jiang, M.; Lu, X. Post-operative Benefit of Compression Therapy after Endovenous Laser Ablation for Uncomplicated Varicose Veins: A Randomised Clinical Trial. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2016, 52, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pihlaja, T. Post-procedural Compression vs. No Compression After Radiofrequency Ablation and Concomitant Foam Sclerotherapy of Varicose Veins: A Randomised Controlled Non-inferiority Trial. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2019, 59, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos Gomes, C.V.; Prado Nunes, M.A.; Navarro, T.P.; Dardik, A. Elastic compression after ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy in overweight patients does not improve primary venous hemodynamics outcomes. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2020, 8, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittaluga, P.; Chastanet, S. Value of postoperative compression after mini-invasive surgical treatment of varicose veins. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2013, 1, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zheng, G.; Ye, B.; Chen, W.; Xie, H.; Zhang, T. Comparison of combined compression and surgery with high ligation-endovenous laser ablation-foam sclerotherapy with compression alone for active venous leg ulcers. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shouler, P.J.; Runchman, P.C. Varicose Veins: Optimum compression after surgery and sclerotherapy. J. R. Nav. Med. Serv. 1990, 76, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohel, M.S.; Barwell, J.R.; Taylor, M.; Chant, T.; Foy, C.; Earnshaw, J.J.; Heather, B.P.; Mitchell, D.C.; Whyman, M.R.; Poskitt, K.R. Long term results of compression therapy alone versus compression plus surgery in chronic venous ulceration (ESCHAR): Randomised controlled trial. Br. Med. J. 2007, 335, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasznai, A.G.; Sigterman, T.A.; Troquay, S.A.M.; Houtermans-Auckel, J.P.; Snoeijs, M.G.J.; Rensma, H.G.; Sikkink, C.J.J.M.; Bouwman, L.M. A randomised controlled trial comparing compression therapy after radiofrequency ablation for primary great saphenous vein incompetence. Phlebology 2016, 31, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, F.; Marone, E.M.; Gasbarro, V.; Bucalossi, M.; Spelta, S.; Amsler, F.; Agnati, M.; Chiesa, R. Multicenter randomized trial comparing compression with elastic stocking versus bandage after surgery for varicose veins. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011, 53, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, R.; Whyman, M.R.; Wilkins, D.C.; Walker, A.J.; Ashley, S. A Randomised Trial of Different Compression Dressings Following Varicose Vein Surgery. Phlebology 1999, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Clark, A.; Shields, D.A. Randomised Clinical Trial of the Duration of Compression Therapy after Varicose Vein Surgery. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2007, 33, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houtermans-Auckel, J.P.; van Rossum, E.; Teijink, J.A.W.; Dahlmans, A.A.H.R.; Eussen, E.F.B.; Nicolai, S.P.A.; Welten, R.T.J. To Wear or not to Wear Compression Stockings after Varicose Vein Stripping: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2009, 38, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onwudike, M.; Abbas, K.; Thompson, P.; McElvenny, D.M. Editor’s Choice Role of Compression After Radiofrequency Ablation of Varicose Veins: A Randomised Controlled Trial☆. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2020, 60, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolotukhin, I.; Demekhova, M.; Ilyukhin, E.; Sonkin, I.; Zakharova, E.; Efremova, O.; Kiseleva, E.; Gavrilov, E. A randomized trial of class II compression sleeves for full legs versus stockings after thermal ablation with phlebectomy. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2021, 9, 1235–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavezzi, A.; Mosti, G.; Colucci, R.; Quinzi, V.; Bastiani, L.; Urso, S.U. Compression with 23 mmHg or 35 mmHg stockings after saphenous catheter foam sclerotherapy and phlebectomy of varicose veins: A randomized controlled study. Phlebology 2019, 34, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nootheti, P.K.; Cadag, K.M.; Magpantay, A.; Goldman, M.P. Efficacy of graduated compression stockings for an additional 3 weeks after sclerotherapy treatment of reticular and telangiectatic leg veins. Dermatol. Surg. 2009, 35, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayo, D.; Blumberg, S.N.; Rockman, C.R.; Sadek, M.; Cayne, N.; Adelman, M.; Kabnick, L.; Maldonado, T.; Berland, T. Compression versus No Compression after Endovenous Ablation of the Great Saphenous Vein: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2017, 38, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, P.; Ramelet, A.A.; Wütschert, R.; Hayoz, D. Compression after sclerotherapy for telangiectasias and reticular leg veins: A randomized controlled study. J. Vasc. Surg. 2007, 45, 1212–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayer, A.; Kuznik, N.; Langan, E.A.; Recke, A.; Recke, A.L.; Faerber, G.; Kaschwich, M.; Kleemann, M.; Kahle, B. Clinical outcome of short-term compression after sclerotherapy for telangiectatic varicose veins. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2021, 9, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sell, H.; Vikatmaa, P.; Albäck, A.; Lepäntalo, M.; Malmivaara, A.; Mahmoud, O.; Venermo, M. Compression therapy versus surgery in the treatment of patients with varicose veins: A RCT. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2014, 47, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich-Schupke, S.; Feldhaus, F.; Altmeyer, P.; Mumme, A.; Stücker, M. Efficacy and comfort of medical compression stockings with low and moderate pressure six weeks after vein surgery. Phlebology 2014, 29, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blecken, S.R.; Villavicencio, J.L.; Kao, T.C. Comparison of elastic versus nonelastic compression in bilateral venous ulcers: A randomized trial. J. Vasc. Surg. 2005, 42, 1150–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordts, P.R.; Hanrahan, L.M.; Rodrigues, A.A.; Jonathan, W.; LaMorte, W.W. A prospective, randomized trial of Unna’s boot versus DuodermCGF hydroactive dressing plus compression in the management of venous leg ulcers. J. Vasc. Surg. 1992, 16, 500–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brizzio, E.; Amsler, F.; Lun, B.; Blättler, W. Comparison of low-strength compression stockings with bandages for the treatment of recalcitrant venous ulcers. J. Vasc. Surg. 2010, 51, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, R.H.; Showalter, D.P. Stockings and the Prevention of Recurrent Venous Ulcers. Dermatol. Surg. 1996, 22, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, A.M.D.; Oliveira, B.G.R.B.D. A study of the Unna Boot compared with the elastic bandage in venous ulcers: A randomized clinical trial. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2015, 23, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, K.J.; Courtney, M.D.; Gibb, M.A.; O’Brien, J.A.; Parker, C.N.; Edwards, H.E. The effectiveness of a four-layer compression bandage system in comparison with Class 3 compression hosiery on healing and quality of life in patients with venous leg ulcers: A randomised controlled trial. Int. Wound J. 2014, 11, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendricks, W.M.; Swallow, R.T. Management of statis leg ulcers with Unna’ s boots versus elastic support stockings. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1985, 12, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stansal, A.; Lazareth, I.; Pasturel, U.M.; Ghaffari, P.; Boursier, V.; Bonhomme, S.; Sfeir, D.; Priollet, P. Compression therapy in 100 consecutive patients with venous leg ulcers. J. Des Mal. Vasc. 2013, 38, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, W.J.; Volek, J.S.; Bush, J.A.; Gotshalk, L.A.; Wagner, P.R.; Gomez, A.L.; Zatsiorsky, V.M.; Duzrte, M.; Ratamess, N.A.; Mazzetti, S.A.; et al. Influence of compression hosiery on physiological responses to standing fatigue in women. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 1849–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westphal, T.; Konschake, W.; Haase, H.; Vollmer, M.; Jünger, M.; Riebe, H. Medical compression stockings on the skin moisture in patients with chronic venous disease. Vasa 2019, 48, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konschake, W.; Riebe, H.; Pediaditi, P.; Haase, H.; Jünger, M.; Lutze, S. Compression in the treatment of chronic venous insufficiency: Efficacy depending on the length of the stocking. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2017, 64, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastel, D. Étude Observationnelle Sur L’Observance Au Traitement Par Bas Médicaux De Compression Chez 144 Patients Consécutifs Souffrant De Varices Primitives Non Compliquées. J. Des Mal. Vasc. 2014, 39, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couzan, S.; Leizorovicz, A.; Laporte, S.; Mismetti, P.; Pouget, J.F.; Chapelle, C.; Quéré, I. A randomized double-blind trial of upward progressive versus degressive compressive stockings in patients with moderate to severe chronic venous insufficiency. J. Vasc. Surg. 2012, 56, 1344–1350.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, R.A.; Duffy, D. Clinical Benefits of Lightweight Compression: Reduction of Venous-Related Symptoms by Ready-to-Wear Lightweight Gradient Compression Hosiery. Dermatol. Surg. 1999, 25, 701–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, Ö.C.; Sevim, S.; Duygu, E.; Tuğral, A.; Bakar, Y. The effects of short-term use of compression stockings on health related quality of life in patients with chronic venous insufficiency. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016, 28, 1988–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosti, G.; Partsch, H. Bandages or double stockings for the initial therapy of venous oedema? A randomized, controlled pilot study. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2013, 46, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belczak, C.E.Q.; De Godoy, J.M.P.; Ramos, R.N.; De Oliveira, M.A.; Belczak, S.Q.; Caffaro, R.A. Is the wearing of elastic stockings for half a day as effective as wearing them for the entire day? Br. J. Dermatol. 2010, 162, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berszakiewicz, A.; Kasperczyk, J.; Sieroń, A.; Krasiński, Z.; Cholewka, A.; Stanek, A. The effect of compression therapy on quality of life in patients with chronic venous disease: A comparative 6-month study. Adv. Dermatol. Allergol. 2021, 38, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference | Design | Patients | CEAP | Invasive Procedure | Study Groups | Compression Type | Daily Regimen | Overall Duration | Results | Intraday Duration (in Hours per Day If Specified) | Results Depending on Intraday Compression Regime |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bootun et al. (2019) [11] | RCT | 204 | C2-5 | RFA/EVLA | 2 groups: compression vs. no compression after initial 24 h of wearing bandages | Class 2, thigh-length | Bandage for 24 h, then 24 h/day | 7 days | Stockings are beneficial if phlebectomy is performed | 24 h | NA |

| Elderman et al. (2014) [14] | RCT | 79 | C2-4 | EVLA | 2 groups: compression stockings vs. no compression after initial 24 h of wearing bandages | Class 2, thigh-length | Bandage for 24 h, then daytime (average: 12.48 h/day) | 2 weeks | Post-procedural pain was slightly, but significantly less if stockings were used | Daytime, 12.48 h on average | NA |

| Ye et al. (2016) [25] | RCT | 400 | C2 | EVLA | 2 groups: compression vs. no compression | Class 2, thigh-length | Daytime (removed only at the measurement) | 2 weeks | Stockings reduce pain and edema during the first week; no influence on QoL and mean time to return to work was found | Daytime | NA |

| Pihlaja et al. (2019) [26] | RCT | 177 | C2–4 | RFA + FS | 2 groups: compression vs. no compression | Class 2, thigh-length | Continuously for 2 days, then daytime for 5 days (removed only at the measurement) | 7 days | No compression was non-inferior to compression in safety and efficacy | Daytime | NA |

| Campos Gomes et al. (2020) [27] | RCT | 92 (135 legs) | C2–6 | FS | 2 groups: compression vs. no compression | Class 2, thigh-length | Bandage for 48 h, then daytime | 3 weeks | Stockings in overweight patients did not decrease need for repeat procedures or the volume of foam | Daytime | NA |

| Pittaluga et al. (2013) [28] | nRCT | 100 | C2–6 | Phlebectomy, ASVAL, stripping | 2 groups: compression vs. compression (if it was necessary) | Class 2 (French), thigh-length | Daytime | 8 days | No benefit from stockings beyond the first postoperative day for pain, ecchymosis, quality of life, and thrombosis | Daytime | NA |

| Liu et al. (2019) [29] | Retrospective Cohort Study | 350 (377 legs) | C6 | HL-EVLA-FS | 2 groups: compression + surgery vs. compression alone | Class 2, thigh-length | Daytime | 2 weeks | Combined treatment can shorten the ulcer healing time and reduce the ulcer recurrence rate compared with compression therapy alone | Daytime | NA |

| Shouler et al. (1989) [30] | RCT | 99 (Group 1), 62 (Group 2) | NR | SF/SP ligation, phlebectomy | 2 groups: VS + compression (2 subgroups: high vs. low) vs. sclero + compression (2 subgroups: stocking-only vs. stocking + bandage) | Low (15 mmHg)/high (40 mmHg) compression stockings, Elastocrepe bandage | During the day (Group 1), not to remove until interim review after 3 weeks (Group 2) | 6 weeks | Low-compression stockings provided adequate support for after surgery and sclerotherapy; bandaging was not required if a high-compression stockings was used | During the day | NA |

| Gohel et al. (2007) [31] | RCT | 500 | C6 | SFJ + GSV stripping to below the knee/SPJ disconnection, + varicosity avulsions | 2 groups: compression vs. compression + VS | Open ulceration—multilayered compression bandaging (40 mmHg); healed legs—Class 2 stockings | During the day for Class-2 stockings | 4 years | Surgical correction in addition to compression bandaging does not improve ulcer healing, but reduces the recurrence of ulcers at four years and results in a greater proportion of ulcer-free time | During the day | NA |

| Krasznai et al. (2015) [32] | RCT | 101 | C2-4 | RFA | 2 groups: compression 4 h vs. compression 72 h | Class 1 + Class 2, thigh-length | Postoperative 4 h vs. 72 h | NA | Stockings for 4 h after procedure are non-inferior in preventing leg edema as for 72 h | Day and night | NA |

| Mariani et al. (2011) [33] | RCT | 60 | C2 | Stripping, perforating veins’ ligation | 2 groups: compression stockings vs. short stretch compression bandages | Class 2, thigh-length (Sigvaris Postoperative Kit) | Day and night (only removed at the visits) | 2 weeks | Short stretch bandage was better than stockings in terms of QoL, edema reduction, and compliance | Day and night | NA |

| Bond et al. (1999) [34] | RCT | 42 | NR | SFL + stripping, phlebectomy | 3 groups: Panelast + TED vs. TED + MediPlus vs. MediPlus + Panelast | MediPlus Class 2 (30–40 mmHg), TED (10–12 mmHg), Panelast (30–38 mmHg) | Continuously | NR | No significant differences between the bandages were found | Continuously | NA |

| Biswas et al. (2007) [35] | RCT | 220 | C2–C4 | SFJ flush-ligation + GSV PIN-stripping + phlebectomy | 2 groups: compression for 1 week vs. compression for 3 weeks | Bandages, then standard full-length TED stockings | Continuously | 1 week vs. 3 weeks | No benefit in wearing compression stockings for more than one week with respect to postoperative pain, number of complications, time to return to work, or patient satisfaction for up to 12 weeks following surgery | Continuously | NA |

| Houtermans-Auckel et al. (2009) [36] | RCT | 104 | C2-3 | Crossectomy + short GSV stripping | 2 groups: compression vs. no compression | Class 2, thigh-length | Bandage for 3 days, then day and night for 2 weeks, then daytime for 2 weeks | 4 weeks | Compression had no additional benefit in limb edema, pain, complications, and return to work | Day and night, then daytime | NA |

| Onwudike et al. (2020) [37] | RCT | 100 | C2–5 | RFA | 2 groups: compression vs. no compression | Class 2, above knee | Day and night for 1 week, then daytime for 1 week | 2 weeks | Compression had no additional benefit | Day and night, then daytime | NA |

| Zolotukhin et al. (2021) [38] | RCT | 187 | C2–4 | RFA, phlebectomy | 2 groups: compression stockings vs. compression sleeves | Class 2 compression sleeves vs. stockings for legs, thigh-length | Day and night for 7 days after the procedure, then >8 h daily | 30 days | QoL improved equally in those who used compression sleeves and stockings | Day and night, then 8 h/day | NA |

| Cavezzi et al. (2019) [39] | RCT | 94 (97 legs) | C2 and > | CFS + phlebectomy | 2 groups: 23 mmHg compression (Group A) vs. 35 mmHg compression (Group B) | 23 mmHg, thigh-length stockings vs. 35 mmHg, thigh-length, then thigh or panty stockings Class 1 (18–21 mmHg) for all patients | 23/35 mmHg MCSs 24 h/day for 7 days, then Class 1 MCSs daytime for 33 days | 7 days, then 33 days (40 days in total) | 35 mmHg stockings provided less-adverse postoperative symptoms and better tissue healing; bioimpedance results confirmed a slightly better edema improvement with 35 mmHg medical compression stocking | 24 h, then daytime | NA |

| Nootheti et al. (2009) [40] | RCT | 29 | C1 | Sclerotherapy | 2 groups: compression vs. no compression | Class 2 30–40 mmHg, thigh-high; Class 1 20–30 mmHg, thigh-high | 24 h/day for 1 week Class 2, then 3 weeks Class 1 vs. 24 h/day for 1 week Class 2 | 4 weeks | Postsclerotherapy hyperpigmentation and bruising was significantly less with the addition of 3 weeks of Class I stockings | 24 h, then while ambulatory | NA |

| Ayo et al. (2016) [41] | RCT | 70 (85 legs) | C2-C5 | EVLA and RFA | 2 groups: compression vs. no compression after initial 24 h of wearing bandages | 30–40 mmHg, thigh-high, bandages | Daily during waking hours | 7 days | Compression therapy does not significantly affect both patients reported and clinical outcomes after GSV ablation in patients with non-ulcerated venous insufficiency | During waking hours | NA |

| Kern et al. (2007) [42] | RCT | 96 | C1 | Sclerotherapy | 2 groups: no compression vs. compression | 23–32 mmHg, thigh-length stocking | Remove at night | 3 weeks | Wearing compression stockings enhanced the efficacy of sclerotherapy of leg telangiectasias by improving clinical vessel disappearance | Remove at night | NA |

| Bayer et al. (2020) [43] | RCT | 50 (100 legs) | C1 | Sclerotherapy | 2 groups: no compression after initial 24 h of wearing bandages (Group A) vs. compression (Group B) | Low-stretch bandages, 18–20 mmHg compression stockings, above the ankle | Continually every day throughout the day | 1 week | One week of compression therapy had no clinical benefit compared with no compression | Throughout the day | NA |

| Sell et al. (2014) [44] | RCT | 153 | C2-C3 | GSV ligation + PIN stripping/SSV ligation + PIN stripping/ AASV or PASV ligation, perforators, local phlebectomy | 2 groups: superficial venous surgery vs. compression | Class 2 compression stockings | All day long during the upright position | 2 years | Superficial venous surgery was better than compression stockings only | All day | NA |

| Reich-Schupke et al. (2014) [45] | RCT | 88 | NR | SFJ/SPJ flush-ligation + GSV/SSV stripping, phlebectomy | 2 groups: low compression (Group A) vs. moderate compression (Group B) | 18–21 mmHg/23–32 mmHg, thigh-high, compression stocking | Whole day, for at least 8 h/day (from the morning after getting up until going to bed) | 6 weeks | 23–32 mmHg compression contributes to a faster elimination of edema, pain, tightness, and discomfort in the early postoperative period, but no differences in the longer postoperative period were found | 29.3% and 42.6% wore stockings for 6–12 h, 68% and 53.2% wore stockings for 12–18 h in Groups A and B, respectively | NA |

| Reference | Design | Patients | CEAP | Study Groups | Ulcer Size | Ulcer Duration | Compression Type | Overall Duration | Results | Intraday Duration (in Hours per Day If Specified) | Results Depending on Intraday Compression Regimen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blecken et al. (2005) [46] | RCT | 12 (24 legs) | C6s | 2 groups: nonelastic compression (group A) vs. elastic compression (group B) | Group A: 48.98 ± 14.13 cm2 vs. Group B: 50.08 ± 18.30 cm2 | NR | Nonelastic compression garment CircAid (group A) vs. Four-layer elastic bandage (group B) | 12 weeks | Non-elastic garment is better than four-layer bandage in healing rate | Entire day | NA |

| Cordts et al. (1992) [47] | RCT | 30 | C6 | 2 groups: Unna’s boot vs. Duoderm CGF plus compression | 9.1 cm2 for Duoderm group, 6.0 cm2 for Unna’s boot group (mean) | 95 weeks (Duoderm group), 96 weeks (Unna’s boot group) (mean) | Unna’s boot vs. Duoderm + Coban wrap | 12 weeks | Duoderm CGF HD is better than Unna’s boot | Entire day | NA |

| Brizzio et al. (2009) [48] | Single-center randomized open-label study | 55 | C6 | 2 groups: compression stockings vs. compression bandages | 13 cm2 (mean) | 27 months (mean) | MCSs 15–20 mm Hg + pads placed above incompetent perforating veins in the ulcer area vs. multi-layer short-stretch bandages + pads | 13 weeks | Stockings and bandages are equally effective in pain relief. | Day and night | NA |

| Samson et al. (1996) [49] | Retrospective Cohort Study | 53 | C6 | NR | 300 mm2 (median) | UlcerCare system (Jobst, Toledo OH) | day and night 15 mmHg, walking hours of day 30 mmHg | 6 weeks (median) | Continued stockings use after ulcer healing prevents most recurrences | Day and night, walking hours | NA |

| de Abreu et al. (2015) [50] | RCT | 18 | C6 | 2 groups: elastic bandage (group A) vs. Unna’s boot (group B) | 15–28 cm2 (median) | NR | Elastic bandage (CCL 3) (group A) vs. Unna’s boot (group B) | 13 weeks | The Unna Boot is better for >10cm2, ulcers, elastic bandage is better for <10 cm2 ulcers | Entire day, and remove at night till morning in group A | NA |

| Finlayson et al. (2014) [51] | RCT | 103 | C6 | 2 groups: compression vs. compression | 4.1 cm2 | 23 weeks (median) | Four-layer bandage system vs. Class 3 hosiery | 24 weeks | Stockings and bandages are equally effective | Compression was removed at night | NA |

| Hendricks et al. (1985) [52] | RCT * | 21 | C6 | 2 groups: compression vs. compression | NR | NR | Unna’s boot vs. open-toe, below the-knee, graded compression elastic support stockings (Futuro Style No. 50) (20–30 mmHg) | 3–115 weeks | Healing rate is the same, while healing times is longer when stockings are used | Stockings were removed at bedtime | NA |

| Stansal et al. (2013) [53] | Prospective observational cohort study | 89 | C5–6 | NR | NR | Class 1, 2, 3 or higher, single-layer bandage; multi-layer bandage | 24 h—for short-stretch bandages, wakefulness—for long-stretch bandages and hosiery | NR | The healing rate was not assessed. Only half of the patients used compression correctly. Only a third complied with regime recommended | 24 h (short-stretch bandages), wakefulness (long-stretch bandages) | NA |

| Author | Design | Patients | CEAP | Duration | Study Groups | Compression Type | Results | Intraday Duration (in Hours per Day If Specified) | Results Depending on Intraday Compression Regimen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kraemer et al. (2000) [54] | Crossover design—experimental prolonged standing | 12 (24 legs) | C0S | 28 days | 3 groups: compression vs. compression vs. compression | Hosiery A, ankle: 7.7, calf: 7.6 thigh: 9.0 vs. Hosiery B, ankle: 7.6; calf: 6.8 thigh: 5.2 vs. Hosiery C, ankle: 15.4, calf: 8.4, thigh: 8.6 mmHg | Different compression stockings reduced leg discomfort and ankle edema | 8 h | NA |

| Westphal et al. (2019) [55] | RCT | 50 | C1-4 | 28 days | 2 groups: compression vs. skin care compression | Class 2, knee-high stocking (AD, Venotrain micro) (23–32 mmHg) vs. MCSs with integrated skincare substances (AD, Venotrain cocoon (23–32 mmHg) | Leg volume decreases under compression treatment | 8 h | NA |

| Konschake et al. (2016) [56] | RCT | 16 | C3-6 | 1 week | 3 groups: compression below-knee vs. compression thigh length vs. compression thigh-length | Below-knee two-component comp stockings (AD, Venotrain) (37 mmHg) vs. thigh-length two-component stockings (AG 37) (37 mmHg) vs. AG 45 (45 mmHg) | Thigh-length stockings were superior to below-knee stockings with regard to volume reduction, venous hemodynamics, and ulcer healing rates | 8 h, inner liner of two-component stockings—during the daytime and night | NA |

| Rastel et al. (2014) [57] | Observational study | 144 | C2-C3 | 1 year | 3 groups: daily wearing (>300 days/year; 8 h/day) vs. seasonal wearing (200–300 days/year; 8 h/day) vs. occasional wearing (<200 days/year; 8 h/day or 200–300 days/year; <8 h/day) | Eighty-nine patients bought and wore at least once the stockings: Class 1 (10–15 mmHg)—6 prescriptions, Class 2 (15–20 mmHg)—74 prescriptions, Class 3 (20–35 mmHg)—3 prescriptions, and unknown—6 | Compliance with MCSs based on patients’ reported outcomes was low | 8 h | NA |

| Couzan et al. (2012) [58] | Double-blind multicenter RCT | 381 | C2-5S | 6 months | 2 groups: progressive compressive stockings vs. degressive compressive stockings | Knee-length PCSs (10 mmHg at the ankle, 23 mmHg at the upper calf) vs. DCSs (30 mmHg at the ankle, 21 mmHg at the upper calf) (Lempy Medical, France) | Progressive stockings were more effective than degressive in pain control | From morning to bedtime | NA |

| Weiss et al. (1999) [59] | Prospective crossover trial | 19 (38 legs) | C0-2S | 4 weeks | 1 group; no compression 2 weeks, compression 4 weeks | RTW lightweight gradient compression stockings (8–15 mmHg and 15–20 mmHg) | Low-compression hosiery improved venous symptoms | During waking hours | NA |

| Oezdemir et al. (2016) [60] | nRCT * | 126 | C2-3 | 4 weeks | 2 groups: compression vs. no compression | Class 2, below-knee, 23–32 mmHg (JOBST brand) | Stockings improved disease-specific and general QoL by reducing venous symptoms | Wake up to before going to bed | NA |

| Mosti et al. (2013) [61] | RCT | 28 (40 legs) | C3 | 4 weeks | 2 groups: compression, inelastic bandage, then elastic stockings (Group A) vs. compression EK, then second stocking added (Group B) | Group A: inelastic bandage + short stretch nonadhesive bandage on the top, then 23–32 mmHg knee high-compression stockings; Group B: knee length grey “liner” from the Mediven Ulcer Kit, then second stocking of Mediven Plus Kit (20 mmHg) was added | The initial improvement in leg volume (1 week) was independent of the pressure applied, and the reduction was maintained by superimposing a second stocking | Day and night, then removed overnight | NA |

| Belczak et al. (2010) [62] | RCT * | 20 (40 legs) | C0-1 | NR | 3 groups: compression entire day (10 h) vs. compression half a day (6 h) vs. no compression | Class 2, three-quarter-length, 20–30 mmHg | Stockings can be helpful in the reduction of evening edema during working hours | 6 h (half day) 10 h (entire day) | 10 h is better than 6 h |

| Author | Design | Patients | CEAP | Duration | Study Groups | Compression Type | Results | Intraday Duration (in Hours per Day If Specified) | Results Depending on Intraday Compression Regime |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berszakiewicz et al. (2019) [63] | Non-randomized comparative study | 180 | C1-6 | 6 months | 6 groups: C1–C6 | Prescribed ready-made compression hosiery (stockings, tights, knee-high socks)/prescribed ready-made 2-in-1 compression systems (VLUs) | Ready-made compression hosiery significantly improves the quality of life in C1–C6 patients | No less than 8 h/day C1—9.33 h C2—9.3 h C3—9.66 h C4—10.2 h C5—9.7 h C6—10.4 h | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mirakhmedova, S.; Amirkhanov, A.; Seliverstov, E.; Efremova, O.; Zolotukhin, I. Daily Duration of Compression Treatment in Chronic Venous Disease Patients: A Systematic Review. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13091316

Mirakhmedova S, Amirkhanov A, Seliverstov E, Efremova O, Zolotukhin I. Daily Duration of Compression Treatment in Chronic Venous Disease Patients: A Systematic Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2023; 13(9):1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13091316

Chicago/Turabian StyleMirakhmedova, Sevara, Amirkhan Amirkhanov, Evgenii Seliverstov, Oksana Efremova, and Igor Zolotukhin. 2023. "Daily Duration of Compression Treatment in Chronic Venous Disease Patients: A Systematic Review" Journal of Personalized Medicine 13, no. 9: 1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13091316