Precision Surgery for Glioblastomas

Abstract

1. Background

- Preparing patients for surgery.

- Defining our resection target for individual patients.

- Understanding what we cannot resect to maintain quality of life.

- Patient selection: do all patients need maximal, safe resection?

- Post-operative management of patients to optimize them for adjuvant oncological therapies.

2. Preparing Patients for Surgery

- Objective assessment and screening for neurological deficits.

- Prehabilitation interventions.

2.1. Identifying PreOperative Deficits

- 10 m Walk Test (gait, walking speed, dynamic balance).

- BERG Balance Scale (gold standard balance tool).

- 9 Hole Peg Test (upper limb function, dexterity, coordination).

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

- Fatigue Severity Scale.

2.2. Prehabilitation Interventions

3. What Should We Resect?

3.1. Extent of Resection vs. Residual Disease

3.2. How Do You Resect All of the Contrast-Enhancing Tumor?

3.3. Resections Beyond the Contrast-Enhanced Tumor

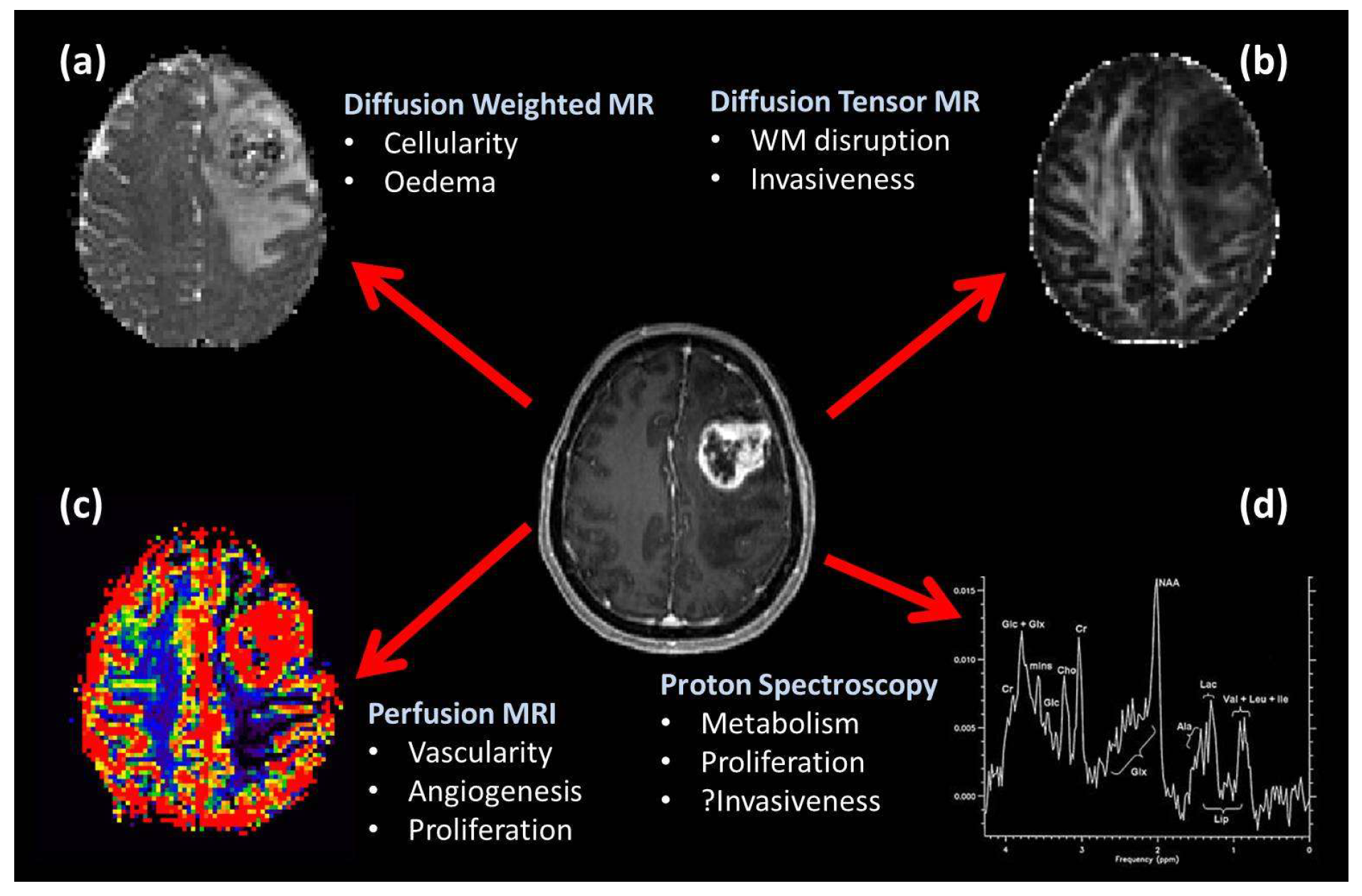

3.4. Imaging Occult Tumor Invasion

3.4.1. FET-PET Imaging

3.4.2. MR Spectroscopy

3.4.3. Diffusion Tensor MRI

3.4.4. Combining Imaging Modalities and Machine Learning

3.4.5. Getting Advanced Imaging into the Operating Theatre

4. What Not to Damage?

4.1. Motor Function

4.2. Language Function

- Word repetition vs. baseline (involving auditory perception, word comprehension, and word production) that identifies function in the left temporoparietal junction, the left inferior frontal gyrus, and motor and premotor regions.

- Verb generation vs. baseline (involving the processes above plus semantic association and linguistic response selection), which identifies the anterior left frontal gyrus and helps determine the dominant hemisphere for language.

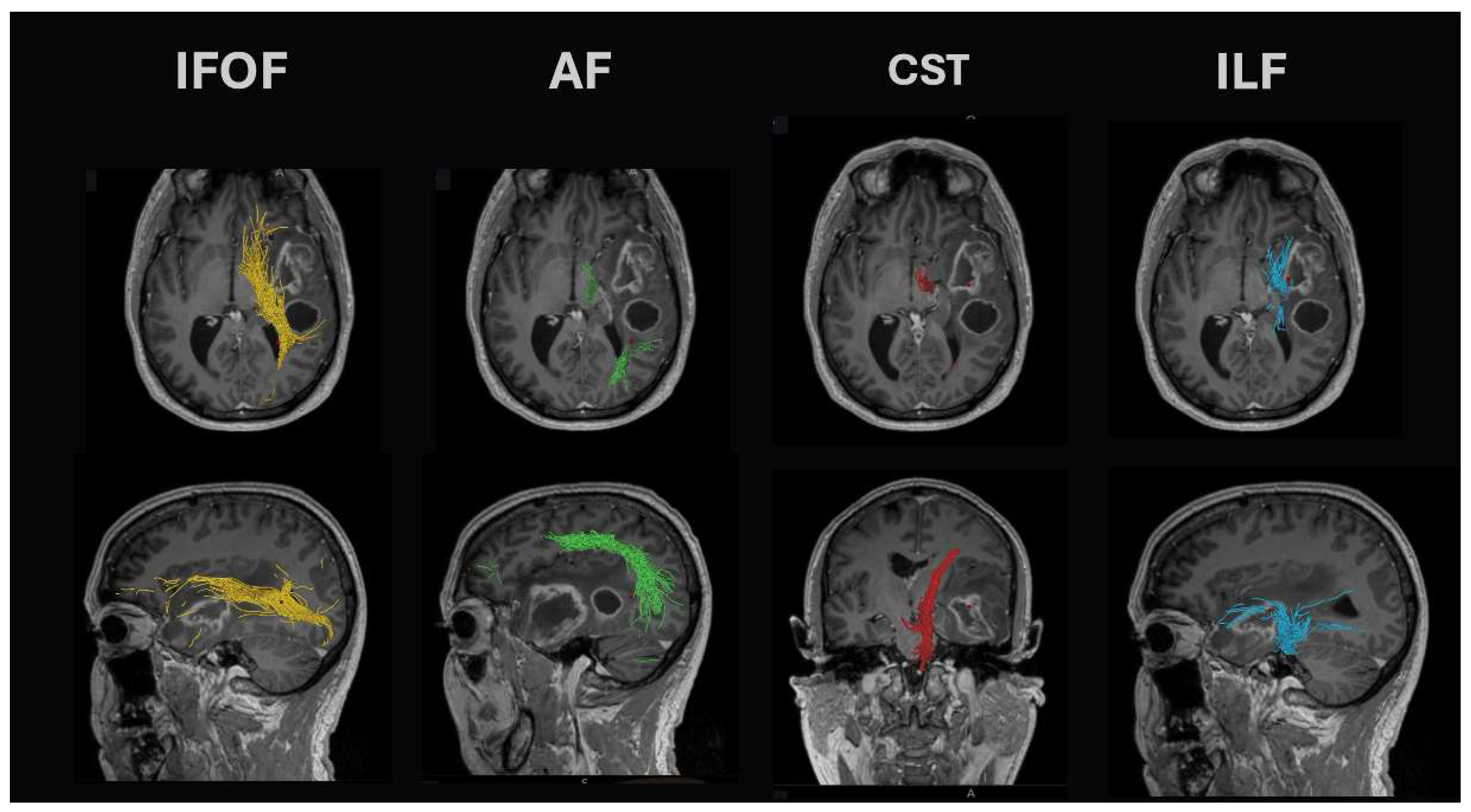

- Arcuate fasciculus: This tract is found in the peri-insular white matter in the circular sulcus of the insula. It links the superior temporal gyrus with the dorsolateral prefrontal and premotor cortices and is found together with the lateral SLF and inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF). Lesions of the arcuate fasciculus lead to phonemic paraphasias, repetitions, and non-fluent ‘expressive’ aphasia.

- Superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF): The temporoparietal branch connects the temporal lobe (posterior inferior, middle, and some superior temporal gyrus) with the parietal cortex (angular and supramarginal gyri). White matter dissection or standard DTI tractography methods cannot separate it from the arcuate fasciculus. Damage leads to fluent aphasia.

- Inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF): Connects the inferior temporal gyrus and runs posteriorly to the superior and middle occipital gyri. It runs between the optic radiation (found more medial) and the more lateral SLF. Seed points for DTI tractography are best seen on coronal views at the level of the middle/inferior temporal gyri. It demonstrates marked intersubject variability in cortical terminations. Damage can lead to problems with reading (alexia).

- Inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF): These fibers pass from the frontal opercular cortex through the temporal stem to run on the roof of the temporal horn back to the occipital cortex. Damage leads to (visual) semantic deficits during naming tasks.

4.3. Visual Function

4.4. Cognitive Function

5. Which Patient?

5.1. Role of Pre-Operative Neurological Deficits and Performance Status

5.2. Role of Age and Supramaximal Resection

5.3. Molecularly Defined Tumor Subtypes

5.4. Using Prognostic Factors in Shared Decision Making

6. Optimizing Post-Operative Status Before Adjuvant Oncology Treatments: Personalizing Rehabilitation

6.1. Lack of Evidence of Rehabilitation in Neuro-Oncology

6.2. Cognitive Rehabilitation for Brain Tumor Patients

- Cognitive screening: A simple screening tool to identify specific cognitive deficits in brain tumor patients is needed. Computerized testing using validated cognitive measures. We have demonstrated that such tools are suitable for use and acceptable for brain tumor patients [84].

- Cognitive rehabilitation: No one size fits all. It is essential to individualize rehabilitation to the patient and their deficits and include patients in any service. Cognitive impairment was described as a significant barrier to rehabilitation, so the interventions must overcome these problems. Some rehabilitation tools developed for specific indications may not be suitable for patients with certain patterns of cognitive deficits.

- Psychology: A significant barrier to cognitive rehabilitation is the lack of trained neuropsychologists. Any intervention to be delivered must account for this and not rely on major neuropsychological input.

- Joining the dots in the community: Rehabilitation services tend to be delivered in hospitals without being extended into the community. This, together with the relative rarity, means there is no expertise in managing patients with brain tumors in the community. Studies in commoner neurological disorders like stroke showed that community services are reluctant to take on stroke patients [120]. Rehabilitation cannot rely purely on community services. The survey identified in the Cochrane review concluded that their intervention trial of multi-disciplinary rehabilitation was “beyond the resources of our hospital to provide therapy for this many patients simultaneously” [118]. As a result, we need to consider how we can provide rehabilitation in patients’ homes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5-ALA | 5-aminolevulinic acid |

| ACSM | American College of Sports Medicine |

| ADC | Apparent diffusion co-efficient |

| AF | Arcuate fasciculus |

| AHP | Allied health professional |

| ASL-CBF | Arterial spin labeled-cerebral blood flow |

| BOLD | Blood oxygen level dependence |

| Cr | Creatine |

| CST | Corticospinal tract |

| DTI | Diffusion tensor imaging |

| FA | Fractional anisotropy |

| FET-PET | O-(2-[18F]-fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine PET imaging |

| FIM | Functional Independence measure |

| fMRI | Functional magnetic resonance imaging |

| HI | Head injury |

| IDH | Isocitrate dehydrogenase |

| IFOF | Inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus |

| ILF | Inferior longitudinal fasciculus |

| iMRI | Intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging |

| MDT | Multidisciplinary tumor board |

| MGMT | O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NAA | N-acetyl–aspartate |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| rCBF | Relative cerebral blood flow |

| rCBV | Relative cerebral blood volume |

| SDM | Shared decision making |

| SLF | Superior longitudinal fasciculus |

| SMA | Supplementary motor area |

References

- Schucht, P.; Beck, J.; Abu-Isa, J.; Andereggen, L.; Murek, M.; Seidel, K.; Stieglitz, L.; Raabe, A. Gross total resection rates in contemporary glioblastoma surgery: Results of an institutional protocol combining 5-aminolevulinic acid intraoperative fluorescence imaging and brain mapping. Neurosurgery 2012, 71, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, M.; van den Bent, M.; Hopkins, K.; Tonn, J.C.; Stupp, R.; Falini, A.; Cohen-Jonathan-Moyal, E.; Frappaz, D.; Henriksson, R.; Balana, C.; et al. EANO guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of anaplastic gliomas and glioblastoma. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, e395–e403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonabend, A.M.; Zacharia, B.E.; Cloney, M.B.; Sonabend, A.; Showers, C.; Ebiana, V.; Nazarian, M.; Swanson, K.R.; Baldock, A.; Brem, H.; et al. Defining Glioblastoma Resectability Through the Wisdom of the Crowd: A Proof-of-Principle Study. Neurosurgery 2017, 80, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodbelt, A.; Greenberg, D.; Winters, T.; Williams, M.; Vernon, S.; Collins, V.P.; National Cancer Information Network Brain Tumour Group. Glioblastoma in England: 2007–2011. Eur. J. Cancer 2015, 51, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stummer, W.; Tonn, J.C.; Mehdorn, H.M.; Nestler, U.; Franz, K.; Goetz, C.; Bink, A.; Pichlmeier, U. Counterbalancing risks and gains from extended resections in malignant glioma surgery: A supplemental analysis from the randomized 5-aminolevulinic acid glioma resection study. Clinical article. J. Neurosurg. 2011, 114, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loosing Myself: The Reality of Life with a Brain Tumour; The Brain Tumour Charity. 2015. Available online: https://www.thebraintumourcharity.org/about-us/our-publications/losing-myself-reality-life-brain-tumour/ (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Warren, K.T.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Strawderman, M.S.; Hussain, A.H.; Ma, H.M.; Milano, M.T.; Mohile, N.A.; Walter, K.A. Time to treatment initiation and outcomes in high-grade glioma patients in rehabilitation: A retrospective cohort study. CNS Oncol. 2020, 9, CNS64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molenaar, C.J.; van Rooijen, S.J.; Fokkenrood, H.J.; Roumen, R.M.; Janssen, L.; Slooter, G.D. Prehabilitation versus no prehabilitation to improve functional capacity, reduce postoperative complications and improve quality of life in colorectal cancer surgery. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 5, CD013259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Mendez, R.; Rastall, R.J.; Sage, W.A.; Oberg, I.; Bullen, G.; Charge, A.L.; Crofton, A.; Santarius, T.; Watts, C.; Price, S.J.; et al. Quality improvement of neuro-oncology services: Integrating the routine collection of patient-reported, health-related quality-of-life measures. Neurooncol. Pract. 2019, 6, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.L.; Winters-Stone, K.M.; Wiskemann, J.; May, A.M.; Schwartz, A.L.; Courneya, K.S.; Zucker, D.S.; Matthews, C.E.; Ligibel, J.A.; Gerber, L.H.; et al. Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors: Consensus Statement from International Multidisciplinary Roundtable. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 2375–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandana, S.R.; Movva, S.; Arora, M.; Singh, T. Primary brain tumors in adults. Am. Fam. Physician 2008, 77, 1423–1430. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, C.X.; Matsuyama, M.; Jones, T.L.; Bashford, J.; Langbecker, D.; Hayes, S.C. Physical activity and exercise in adults diagnosed with primary brain cancer: A systematic review. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2021, 153, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, C.X.; Gildea, G.C.; Spence, R.R.; Jones, T.L.; Eliadis, P.; Walker, D.; Donaghue, A.; Bettington, C.; Keller, J.; Pickersgill, D.; et al. The safety, feasibility, and efficacy of an 18-week exercise intervention for adults with primary brain cancer—The BRACE study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 46, 2317–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, F.K.; Forsting, M.; Sartor, K.; Adams, H.P.; Kunze, S. Early postoperative magnetic resonance imaging after resection of malignant glioma: Objective evaluation of residual tumor and its influence on regrowth and prognosis. Neurosurgery 1994, 34, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, M.; Abi-Said, D.; Fourney, D.R.; Gokaslan, Z.L.; Shi, W.; DeMonte, F.; Lang, F.F.; McCutcheon, I.E.; Hassenbusch, S.J.; Holland, E.; et al. A multivariate analysis of 416 patients with glioblastoma multiforme: Prognosis, extent of resection, and survival. J. Neurosurg. 2001, 95, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanai, N.; Polley, M.Y.; McDermott, M.W.; Parsa, A.T.; Berger, M.S. An extent of resection threshold for newly diagnosed glioblastomas. J. Neurosurg. 2011, 115, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.J.; Brennan, M.C.; Li, M.; Church, E.W.; Brandmeir, N.J.; Rakszawski, K.L.; Patel, A.S.; Rizk, E.B.; Suki, D.; Sawaya, R.; et al. Association of the Extent of Resection with Survival in Glioblastoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1460–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellingson, B.M.; Abrey, L.E.; Nelson, S.J.; Kaufmann, T.J.; Garcia, J.; Chinot, O.; Saran, F.; Nishikawa, R.; Henriksson, R.; Mason, W.P.; et al. Validation of postoperative residual contrast-enhancing tumor volume as an independent prognostic factor for overall survival in newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncol. 2018, 20, 1240–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stummer, W.; Meinel, T.; Ewelt, C.; Martus, P.; Jakobs, O.; Felsberg, J.; Reifenberger, G. Prospective cohort study of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide chemotherapy for glioblastoma patients with no or minimal residual enhancing tumor load after surgery. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2012, 108, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willems, P.W.; Taphoorn, M.J.; Burger, H.; Berkelbach van der Sprenkel, J.W.; Tulleken, C.A. Effectiveness of neuronavigation in resecting solitary intracerebral contrast-enhancing tumors: A randomized controlled trial. J. Neurosurg. 2006, 104, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.S.; Carroll, K.T.; Koch, M.; DiCesare, J.A.T.; Reitz, K.; Frosch, M.; Barker, F.G., 2nd; Cahill, D.P.; Curry, W.T., Jr. Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Mutations in Low-Grade Gliomas Correlate with Prolonged Overall Survival in Older Patients. Neurosurgery 2019, 84, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stummer, W.; Novotny, A.; Stepp, H.; Goetz, C.; Bise, K.; Reulen, H.J. Fluorescence-guided resection of glioblastoma multiforme by using 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced porphyrins: A prospective study in 52 consecutive patients. J. Neurosurg. 2000, 93, 1003–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stummer, W.; Pichlmeier, U.; Meinel, T.; Wiestler, O.D.; Zanella, F.; Reulen, H.-J. Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma: A randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006, 7, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez Valle, R.; Slof, J.; Galvan, J.; Arza, C.; Romariz, C.; Vidal, C. Observational, retrospective study of the effectiveness of 5-aminolevulinic acid in malignant glioma surgery in Spain (The VISIONA study). Neurologia 2014, 29, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schucht, P.; Murek, M.; Jilch, A.; Seidel, K.; Hewer, E.; Wiest, R.; Raabe, A.; Beck, J. Early re-do surgery for glioblastoma is a feasible and safe strategy to achieve complete resection of enhancing tumor. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockhammer, F.; Misch, M.; Horn, P.; Koch, A.; Fonyuy, N.; Plotkin, M. Association of F18-fluoro-ethyl-tyrosin uptake and 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced fluorescence in gliomas. Acta Neurochir. 2009, 151, 1377–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muther, M.; Koch, R.; Weckesser, M.; Sporns, P.; Schwindt, W.; Stummer, W. 5-Aminolevulinic Acid Fluorescence-Guided Resection of 18F-FET-PET Positive Tumor Beyond Gadolinium Enhancing Tumor Improves Survival in Glioblastoma. Neurosurgery 2019, 85, E1020–E1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, K.; Tamura, K.; Hara, S.; Inaji, M.; Tanaka, Y.; Kobayashi, D.; Sugawara, T.; Wakimoto, H.; Nariai, T.; Ishii, K.; et al. Correlation of Intraoperative 5-ALA-Induced Fluorescence Intensity and Preoperative 11C-Methionine PET Uptake in Glioma Surgery. Cancers 2022, 14, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bonis, P.; Anile, C.; Pompucci, A.; Fiorentino, A.; Balducci, M.; Chiesa, S.; Lauriola, L.; Maira, G.; Mangiola, A. The influence of surgery on recurrence pattern of glioblastoma. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2013, 115, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Saffari, S.E.; Low, D.C.Y.; Lin, X.; Ker, J.R.X.; Ang, S.Y.L.; Ng, W.H.; Wan, K.R. Lobectomy versus gross total resection for glioblastoma multiforme: A systematic review and individual-participant data meta-analysis. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 115, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidel, O.; Burth, S.; Neumann, J.O.; Kieslich, P.J.; Sahm, F.; Jungk, C.; Kickingereder, P.; Bickelhaupt, S.; Mundiyanapurath, S.; Baumer, P.; et al. Tumor Infiltration in Enhancing and Non-Enhancing Parts of Glioblastoma: A Correlation with Histopathology. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.M.; Suki, D.; Hess, K.; Sawaya, R. The influence of maximum safe resection of glioblastoma on survival in 1229 patients: Can we do better than gross-total resection? J. Neurosurg. 2016, 124, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incekara, F.; Koene, S.; Vincent, A.; van den Bent, M.J.; Smits, M. Association Between Supratotal Glioblastoma Resection and Patient Survival: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2019, 127, 617–624.e612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karschnia, P.; Vogelbaum, M.A.; van den Bent, M.; Cahill, D.P.; Bello, L.; Narita, Y.; Berger, M.S.; Weller, M.; Tonn, J.C. Evidence-based recommendations on categories for extent of resection in diffuse glioma. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karschnia, P.; Young, J.S.; Dono, A.; Hani, L.; Sciortino, T.; Bruno, F.; Juenger, S.T.; Teske, N.; Morshed, R.A.; Haddad, A.F.; et al. Prognostic validation of a new classification system for extent of resection in glioblastoma: A report of the RANO resect group. Neuro-Oncology 2023, 25, 940–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Certo, F.; Altieri, R.; Maione, M.; Schonauer, C.; Sortino, G.; Fiumano, G.; Tirro, E.; Massimino, M.; Broggi, G.; Vigneri, P.; et al. FLAIRectomy in Supramarginal Resection of Glioblastoma Correlates with Clinical Outcome and Survival Analysis: A Prospective, Single Institution, Case Series. Oper. Neurosurg. 2021, 20, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verburg, N.; Koopman, T.; Yaqub, M.M.; Hoekstra, O.S.; Lammertsma, A.A.; Barkhof, F.; Pouwels, P.J.W.; Reijneveld, J.C.; Heimans, J.J.; Rozemuller, A.J.M.; et al. Improved detection of diffuse glioma infiltration with imaging combinations: A diagnostic accuracy study. Neuro-Oncol. 2020, 22, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimou, J.; Beland, B.; Kelly, J. Supramaximal resection: A systematic review of its safety, efficacy and feasibility in glioblastoma. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 72, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.H.; Mahavadi, A.; Di, L.; Sanjurjo, A.; Eichberg, D.G.; Borowy, V.; Figueroa, J.; Luther, E.; de la Fuente, M.I.; Semonche, A.; et al. Survival benefit of lobectomy for glioblastoma: Moving towards radical supramaximal resection. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2020, 148, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, L.; Shah, A.H.; Mahavadi, A.; Eichberg, D.G.; Reddy, R.; Sanjurjo, A.D.; Morell, A.A.; Lu, V.M.; Ampie, L.; Luther, E.M.; et al. Radical supramaximal resection for newly diagnosed left-sided eloquent glioblastoma: Safety and improved survival over gross-total resection. J. Neurosurg. 2023, 138, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.B.; Roh, T.H.; Kang, S.G.; Kim, S.H.; Moon, J.H.; Kim, E.H.; Ahn, S.S.; Choi, H.J.; Cho, J.; Suh, C.O.; et al. Survival, Prognostic Factors, and Volumetric Analysis of Extent of Resection for Anaplastic Gliomas. Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 52, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, C.A.; Baker, C.M.; Conner, A.K.; Burks, J.D.; Bonney, P.A.; Briggs, R.G.; Smitherman, A.D.; Battiste, J.D.; Sughrue, M.E. An Examination of the Role of Supramaximal Resection of Temporal Lobe Glioblastoma Multiforme. World Neurosurg. 2018, 114, e747–e755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, M.; Potthoff, A.L.; Keil, V.C.; Guresir, A.; Weller, J.; Borger, V.; Hamed, M.; Waha, A.; Vatter, H.; Guresir, E.; et al. Surgery for temporal glioblastoma: Lobectomy outranks oncosurgical-based gross-total resection. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2019, 145, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.; Ilic, I.; Potthoff, A.L.; Hamed, M.; Schafer, N.; Velten, M.; Guresir, E.; Herrlinger, U.; Borger, V.; Vatter, H.; et al. Safety metric profiling in surgery for temporal glioblastoma: Lobectomy as a supra-total resection regime preserves perioperative standard quality rates. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2020, 149, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasgupta, A.; Geraghty, B.; Maralani, P.J.; Malik, N.; Sandhu, M.; Detsky, J.; Tseng, C.L.; Soliman, H.; Myrehaug, S.; Husain, Z.; et al. Quantitative mapping of individual voxels in the peritumoral region of IDH-wildtype glioblastoma to distinguish between tumor infiltration and edema. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2021, 153, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, S. The role of advanced MR imaging in understanding brain tumour pathology. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2007, 21, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karschnia, P.; Smits, M.; Reifenberger, G.; Le Rhun, E.; Ellingson, B.M.; Galldiks, N.; Kim, M.M.; Huse, J.T.; Schnell, O.; Harter, P.N.; et al. A framework for standardised tissue sampling and processing during resection of diffuse intracranial glioma: Joint recommendations from four RANO groups. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, e438–e450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, S.J.; Jena, R.; Burnet, N.G.; Hutchinson, P.J.; Dean, A.F.; Pena, A.; Pickard, J.D.; Carpenter, T.A.; Gillard, J.H. Improved Delineation of Glioma Margins and Regions of Infiltration with the Use of Diffusion Tensor Imaging: An Image-Guided Biopsy Study. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2006, 27, 1969–1974. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sahm, F.; Capper, D.; Jeibmann, A.; Habel, A.; Paulus, W.; Troost, D.; von Deimling, A. Addressing diffuse glioma as a systemic brain disease with single-cell analysis. Arch. Neurol. 2012, 69, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.L.; Akyurek, S.; Avalos, T.; Rebueno, N.; Spicer, C.; Garcia, J.; Famiglietti, R.; Allen, P.K.; Chao, K.S.; Mahajan, A.; et al. Evaluation of peritumoral edema in the delineation of radiotherapy clinical target volumes for glioblastoma. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2007, 68, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchmann, N.; Gempt, J.; Ryang, Y.M.; Pyka, T.; Kirschke, J.S.; Meyer, B.; Ringel, F. Can Early Postoperative O-(2-(18F)Fluoroethyl)-l-Tyrosine Positron Emission Tomography After Resection of Glioblastoma Predict the Location of Later Tumor Recurrence? World Neurosurg. 2019, 121, e467–e474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ort, J.; Hamou, H.A.; Kernbach, J.M.; Hakvoort, K.; Blume, C.; Lohmann, P.; Galldiks, N.; Heiland, D.H.; Mottaghy, F.M.; Clusmann, H.; et al. 18F-FET-PET-guided gross total resection improves overall survival in patients with WHO grade III/IV glioma: Moving towards a multimodal imaging-guided resection. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2021, 155, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laprie, A.; Catalaa, I.; Cassol, E.; McKnight, T.R.; Berchery, D.; Marre, D.; Bachaud, J.M.; Berry, I.; Moyal, E.C. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging in newly diagnosed glioblastoma: Predictive value for the site of postradiotherapy relapse in a prospective longitudinal study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2008, 70, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deviers, A.; Ken, S.; Filleron, T.; Rowland, B.; Laruelo, A.; Catalaa, I.; Lubrano, V.; Celsis, P.; Berry, I.; Mogicato, G.; et al. Evaluation of the lactate-to-N-acetyl-aspartate ratio defined with magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging before radiation therapy as a new predictive marker of the site of relapse in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2014, 90, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, C.A.; Bhatia, S.; Morell, A.A.; Daggubati, L.C.; Merenzon, M.A.; Sheriff, S.A.; Luther, E.; Chandar, J.; Levy, A.S.; Metzler, A.R.; et al. Metabolic signatures derived from whole-brain MR-spectroscopy identify early tumor progression in high-grade gliomas using machine learning. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2024, 170, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sternberg, E.J.; Lipton, M.L.; Burns, J. Utility of diffusion tensor imaging in evaluation of the peritumoral region in patients with primary and metastatic brain tumors. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2014, 35, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menna, G.; Marinno, S.; Valeri, F.; Mahadevan, S.; Mattogno, P.P.; Gaudino, S.; Olivi, A.; Doglietto, F.; Berger, M.S.; Della Pepa, G.M. Diffusion tensor imaging in detecting gliomas sub-regions of infiltration, local and remote recurrences: A systematic review. Neurosurg. Rev. 2024, 47, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzi, F.M.; Mayrand, R.C.; Wan, Y.; Price, S.J. Predicting glioblastoma progression using MR diffusion tensor imaging: A systematic review. J. Neuroimaging 2025, 35, e13251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, S.J.; Pena, A.; Burnet, N.G.; Jena, R.; Green, H.A.; Carpenter, T.A.; Pickard, J.D.; Gillard, J.H. Tissue signature characterisation of diffusion tensor abnormalities in cerebral gliomas. Eur. Radiol. 2004, 14, 1909–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.-L.; van der Horn, A.; Larkin, T.J.; Boonzaier, N.R.; Matys, T.; Price, S.J. Extent of resection of peritumoural DTI abnormality as a predictor of survival in adult glioblastoma patients. J. Neurosurg. 2017, 126, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinges, M.H.; Nguyen, H.H.; Krings, T.; Hutter, B.O.; Rohde, V.; Gilsbach, J.M. Course of brain shift during microsurgical resection of supratentorial cerebral lesions: Limits of conventional neuronavigation. Acta Neurochir. 2004, 146, 369–377, discussion 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgiopoulos, M.; Tsonis, J.; Apostolopoulou, C.; Constantoyannis, C. Intraoperatively updated navigation systems: The solution to brain shift. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Trials Nerv. Syst. Dis. 2017, 2, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGirt, M.J.; Mukherjee, D.; Chaichana, K.L.; Than, K.D.; Weingart, J.D.; Quinones-Hinojosa, A. Association of surgically acquired motor and language deficits on overall survival after resection of glioblastoma multiforme. Neurosurgery 2009, 65, 463–469, discussion 469–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witt Hamer, P.C.; Robles, S.G.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Duffau, H.; Berger, M.S. Impact of intraoperative stimulation brain mapping on glioma surgery outcome: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2559–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Pena, M.J.; Gil-Robles, S.; de Vega, V.M.; Aracil, C.; Acevedo, A.; Rodriguez, M.R. A Practical Approach to Imaging of the Supplementary Motor Area and Its Subcortical Connections. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2020, 20, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizzi, A.; Blasi, V.; Falini, A.; Ferroli, P.; Cadioli, M.; Danesi, U.; Aquino, D.; Marras, C.; Caldiroli, D.; Broggi, G. Presurgical functional MR imaging of language and motor functions: Validation with intraoperative electrocortical mapping. Radiology 2008, 248, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.C.; Ward, H.A.; Sharbrough, F.W.; Meyer, F.B.; Marsh, W.R.; Raffel, C.; So, E.L.; Cascino, G.D.; Shin, C.; Xu, Y.; et al. Assessment of functional MR imaging in neurosurgical planning. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1999, 20, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nimsky, C.; Ganslandt, O.; Hastreiter, P.; Wang, R.; Benner, T.; Sorensen, A.G.; Fahlbusch, R. Intraoperative diffusion-tensor MR imaging: Shifting of white matter tracts during neurosurgical procedures—Initial experience. Radiology 2005, 234, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.S.; Gogos, A.J.; Aabedi, A.A.; Morshed, R.A.; Pereira, M.P.; Lashof-Regas, S.; Mansoori, Z.; Luks, T.; Hervey-Jumper, S.L.; Villanueva-Meyer, J.E.; et al. Resection of supplementary motor area gliomas: Revisiting supplementary motor syndrome and the role of the frontal aslant tract. J. Neurosurg. 2022, 136, 1278–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, F.E.; Boulanouar, K.; Lotterie, J.A.; Mejdoubi, M.; LeSage, J.P.; Berry, I. Language functional magnetic resonance imaging in preoperative assessment of language areas: Correlation with direct cortical stimulation. Neurosurgery 2003, 52, 1335–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutten, G.J.; Ramsey, N.F.; van Rijen, P.C.; van Veelen, C.W. Reproducibility of fMRI-determined language lateralization in individual subjects. Brain Lang. 2002, 80, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, M.G.; Price, S.J.; Suckling, J. Functional connectivity networks for preoperative brain mapping in neurosurgery. J. Neurosurg. 2016, 126, 1941–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moretto, M.; Luciani, B.F.; Zigiotto, L.; Saviola, F.; Tambalo, S.; Cabalo, D.G.; Annicchiarico, L.; Venturini, M.; Jovicich, J.; Sarubbo, S. Resting State Functional Networks in Gliomas: Validation with Direct Electric Stimulation Using a New Tool for Planning Brain Resections. Neurosurgery 2024, 95, 1358–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamao, Y.; Matsumoto, R.; Kikuchi, T.; Yoshida, K.; Kunieda, T.; Miyamoto, S. Intraoperative Brain Mapping by Cortico-Cortical Evoked Potential. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 635453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega-Zelaya, L.; Pulido, P.; Sola, R.G.; Pastor, J. Intraoperative Cortico-Cortical Evoked Potentials for Monitoring Language Function during Brain Tumor Resection in Anesthetized Patients. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2023, 22, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bykanov, A.E.; Pitskhelauri, D.I.; Titov, O.Y.; Lin, M.C.; Gulaev, E.V.; Ogurtsova, A.A.; Maryashev, S.A.; Zhukov, V.Y.; Buklina, S.B.; Lubnin, A.Y.; et al. Broca‘s area intraoperative mapping with cortico-cortical evoked potentials. Vopr. Neirokhirurgii Im. NN Burdenko 2020, 84, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, A.; Hazelton, C.; Henderson, C.A.; Angilley, J.; Dhillon, B.; Langhorne, P.; Livingstone, K.; Munro, F.A.; Orr, H.; Rowe, F.J.; et al. Interventions for visual field defects in patients with stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, CD008388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, D. Homonymous hemianopia: Challenges and solutions. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2014, 8, 1919–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, C.S.; French, J.M.; Bates, D.; Cartlidge, N.E.; Venables, G.S.; James, O.F. Recovery of visual fields in acute stroke: Homonymous hemianopia associated with adverse prognosis. Age Ageing 1989, 18, 419–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Kedar, S.; Lynn, M.J.; Newman, N.J.; Biousse, V. Natural history of homonymous hemianopia. Neurology 2006, 66, 901–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pambakian, A.L.; Wooding, D.S.; Patel, N.; Morland, A.B.; Kennard, C.; Mannan, S.K. Scanning the visual world: A study of patients with homonymous hemianopia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2000, 69, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noll, K.R.; Bradshaw, M.E.; Weinberg, J.S.; Wefel, J.S. Neurocognitive functioning is associated with functional independence in newly diagnosed patients with temporal lobe glioma. Neuro-Oncol. Pract. 2017, 5, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.; Stephenson, J.M.; Price, S.J. A systematic review of cognitive function in patients with glioblastoma undergoing surgery. Neurooncol. Pract. 2020, 7, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Garcia, R.; Owen, M.; McDonald, A.; Woodberry, E.; Assem, M.; Coelho, P.; Morris, R.C.; Price, S.J.; Santarius, T.; Suckling, J.; et al. Assessment of neuropsychological function in brain tumor treatment: A comparison of traditional neuropsychological assessment with app-based cognitive screening. Acta Neurochir. 2022, 164, 2021–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.; Masina, R.; Morales, C.; Burton, K.; Wan, Y.; Joannides, A.; Mair, R.J.; Morris, R.C.; Santarius, T.; Manly, T.; et al. A Prospective Study of Longitudinal Risks of Cognitive Deficit for People Undergoing Glioblastoma Surgery Using a Tablet Computer Cognition Testing Battery: Towards Personalized Understanding of Risks to Cognitive Function. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.; Dijkshoorn, A.B.C.; Li, C.; Manly, T.; Price, S.J. Glioblastoma surgery related emotion recognition deficits are associated with right cerebral hemisphere tract changes. Brain Commun. 2020, 2, fcaa169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, M.G.; Price, S.J.; Suckling, J. Connectome analysis for pre-operative brain mapping in neurosurgery. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2016, 30, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Li, C.; Cui, Z.; Mayrand, R.C.; Zou, J.; Wong, A.; Sinha, R.; Matys, T.; Schonlieb, C.B.; Price, S.J. Structural connectome quantifies tumour invasion and predicts survival in glioblastoma patients. Brain 2023, 146, 1714–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, A.; Cuesta, P.; Kato, T.; Arahata, Y.; Iwata, K.; Yamagishi, M.; Kuratsubo, I.; Kato, K.; Bundo, M.; Diers, K.; et al. Early functional network alterations in asymptomatic elders at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzman, R.; Terry, R.; DeTeresa, R.; Brown, T.; Davies, P.; Fuld, P.; Renbing, X.; Peck, A. Clinical, pathological, and neurochemical changes in dementia: A subgroup with preserved mental status and numerous neocortical plaques. Ann. Neurol. 1988, 23, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucci, M.; Mapelli, D.; Mondini, S. Cognitive Reserve Index questionnaire (CRIq): A new instrument for measuring cognitive reserve. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2012, 24, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, P.; Moreira, P.; Magalhaes, R.; Costa, P.; Santos, N.; Zihl, J.; Soares, J.; Sousa, N. The functional connectome of cognitive reserve. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2016, 37, 3310–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, S.J.; Whittle, I.R.; Ashkan, K.; Grundy, P.; Cruickshank, G.; Group, U.-H.S. NICE guidance on the use of carmustine wafers in high grade gliomas: A national study on variation in practice. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2012, 26, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagberg, L.M.; Drewes, C.; Jakola, A.S.; Solheim, O. Accuracy of operating neurosurgeons’ prediction of functional levels after intracranial tumor surgery. J. Neurosurg. 2017, 126, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; et al. Radiotherapy plus Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide for Glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinaro, A.M.; Hervey-Jumper, S.; Morshed, R.A.; Young, J.; Han, S.J.; Chunduru, P.; Zhang, Y.; Phillips, J.J.; Shai, A.; Lafontaine, M.; et al. Association of Maximal Extent of Resection of Contrast-Enhanced and Non-Contrast-Enhanced Tumor with Survival Within Molecular Subgroups of Patients with Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi, T.; Sonoda, Y.; Shibahara, I.; Saito, R.; Kanamori, M.; Kumabe, T.; Tominaga, T. Impact of gross total resection in patients with WHO grade III glioma harboring the IDH 1/2 mutation without the 1p/19q co-deletion. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2016, 129, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegi, M.E.; Diserens, A.C.; Gorlia, T.; Hamou, M.F.; de Tribolet, N.; Weller, M.; Kros, J.M.; Hainfellner, J.A.; Mason, W.; Mariani, L.; et al. MGMT Gene Silencing and Benefit from Temozolomide in Glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roder, C.; Stummer, W.; Coburger, J.; Scherer, M.; Haas, P.; von der Brelie, C.; Kamp, M.A.; Lohr, M.; Hamisch, C.A.; Skardelly, M.; et al. Intraoperative MRI-Guided Resection Is Not Superior to 5-Aminolevulinic Acid Guidance in Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma: A Prospective Controlled Multicenter Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 5512–5523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halldorsson, S.; Nagymihaly, R.M.; Patel, A.; Brandal, P.; Panagopoulos, I.; Leske, H.; Lund-Iversen, M.; Sahm, F.; Vik-Mo, E.O. Accurate and comprehensive evaluation of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase promoter methylation by nanopore sequencing. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2024, 50, e12984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.B.; Guo, F.; Xu, Z.L.; Li, C.; Wei, W.; Tian, P.; Liu, T.T.; Liu, L.; Chen, G.; Ye, J.; et al. Radiomics signature: A potential biomarker for the prediction of MGMT promoter methylation in glioblastoma. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2017, 47, 1380–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, M.B.; Edgman-Levitan, S. Shared decision making--pinnacle of patient-centered care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 780–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiggelbout, A.M.; Pieterse, A.H.; De Haes, J.C. Shared decision making: Concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 1172–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Legare, F.; Simmons, M.B.; McNamara, K.; McCaffery, K.; Trevena, L.J.; Hudson, B.; Glasziou, P.P.; Del Mar, C.B. Shared decision making: What do clinicians need to know and why should they bother? Med. J. Aust. 2014, 201, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hormazabal-Salgado, R.; Whitehead, D.; Osman, A.D.; Hills, D. Person-Centred Decision-Making in Mental Health: A Scoping Review. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2024, 45, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherer, M.; Meyers, C.A.; Bergloff, P. Efficacy of postacute brain injury rehabilitation for patients with primary malignant brain tumors. Cancer 1997, 80, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.E.; Cifu, D.X.; Keyser-Marcus, L. Functional outcome after brain tumor and acute stroke: A comparative analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1998, 79, 1386–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’’Dell, M.W.; Barr, K.; Spanier, D.; Warnick, R.E. Functional outcome of inpatient rehabilitation in persons with brain tumors. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1998, 79, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.E.; Cifu, D.X.; Keyser-Marcus, L. Functional outcomes in patients with brain tumor after inpatient rehabilitation: Comparison with traumatic brain injury. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2000, 79, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.E.; Wartella, J.E.; Kreutzer, J.S. Functional outcomes and quality of life in patients with brain tumors: A preliminary report. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2001, 82, 1540–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniak, C.M.; Sliwa, J.A.; Heinemann, A.W.; Semik, P.E. Functional outcomes of persons with brain tumors after inpatient rehabilitation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2001, 82, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, A.; Parisi, C.; Di Lelio, M.; Zizzari, A.; Petreri, G.; Giovannelli, M.; Pompili, A. Home rehabilitation for brain tumor patients. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 26, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tang, V.; Rathbone, M.; Park Dorsay, J.; Jiang, S.; Harvey, D. Rehabilitation in primary and metastatic brain tumours: Impact of functional outcomes on survival. J. Neurol. 2008, 255, 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geler-Kulcu, D.; Gulsen, G.; Buyukbaba, E.; Ozkan, D. Functional recovery of patients with brain tumor or acute stroke after rehabilitation: A comparative study. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 16, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.B.; Parsons, H.A.; Shin, K.Y.; Guo, Y.; Konzen, B.S.; Yadav, R.R.; Smith, D.W. Comparison of functional outcomes in low- and high-grade astrocytoma rehabilitation inpatients. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010, 89, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartolo, M.; Zucchella, C.; Pace, A.; Lanzetta, G.; Vecchione, C.; Bartolo, M.; Grillea, G.; Serrao, M.; Tassorelli, C.; Sandrini, G.; et al. Early rehabilitation after surgery improves functional outcome in inpatients with brain tumours. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2012, 107, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.R.; Chun, M.H.; Han, E.Y.; Kim, D.K. Fatigue assessment and rehabilitation outcomes in patients with brain tumors. Support. Care Cancer 2012, 20, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Amatya, B.; Drummond, K.; Galea, M. Effectiveness of integrated multidisciplinary rehabilitation in primary brain cancer survivors in an Australian community cohort: A controlled clinical trial. J. Rehabil. Med. 2014, 46, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, F.; Amatya, B.; Ng, L.; Drummond, K.; Galea, M. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation after primary brain tumour treatment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, CD009509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffares, I.; Merriman, N.A.; Doyle, F.; Horgan, F.; Hickey, A. Designing stroke services for the delivery of cognitive rehabilitation: A qualitative study with stroke rehabilitation professionals. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2021, 33, 24–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodtmann, A.; Billett, A.; Telfer, R.; Adkins, K.; White, L.; McCambridge, L.J.E.; Burrell, L.M.; Thijs, V.; Kramer, S.; Werden, E.; et al. ZOom Delivered Intervention Against Cognitive decline (ZODIAC) COVID-19 pandemic adaptations to the Post-Ischaemic Stroke Cardiovascular Exercise Study (PISCES): Protocol for a randomised controlled trial of remotely delivered fitness training for brain health. Trials 2024, 25, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Imaging Type | Imaging Method | AUC (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Conventional imaging | T1-weighted | 0.58 (0.47–0.69) |

| T2-weighted | 0.60 (0.47–0.73) | |

| FLAIR imaging | 0.62 (0.49–0.74) | |

| Diffusion MRI | Apparent diffusion co-efficient (ADC) | 0.66 (0.54–0.78) |

| Fractional anisotropy (FA) | 0.64 (0.53–0.76) | |

| Perfusion MRI | Relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV) | 0.70 (0.58–0.82) |

| Relative cerebral blood flow (rCBF) | 0.67 (0.56–0.78) | |

| Arterial spin labelled CBF (ASL-CBF) | 0.53 (0.42–0.64) | |

| MR Spectroscopy | Choline-to-NAA Index | 0.64 (0.50–0.79) |

| PET Imaging | [18F]-FET | 0.74 (0.62–0.86) |

| Combination of Imaging | ADC/FET | 0.89 (0.80–0.97) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Price, S.J.; Hughes, J.G.; Jain, S.; Kelly, C.; Sederias, I.; Cozzi, F.M.; Fares, J.; Li, Y.; Kennedy, J.C.; Mayrand, R.; et al. Precision Surgery for Glioblastomas. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15030096

Price SJ, Hughes JG, Jain S, Kelly C, Sederias I, Cozzi FM, Fares J, Li Y, Kennedy JC, Mayrand R, et al. Precision Surgery for Glioblastomas. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(3):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15030096

Chicago/Turabian StylePrice, Stephen J., Jasmine G. Hughes, Swati Jain, Caroline Kelly, Ioana Sederias, Francesca M. Cozzi, Jawad Fares, Yonghao Li, Jasmine C. Kennedy, Roxanne Mayrand, and et al. 2025. "Precision Surgery for Glioblastomas" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 3: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15030096

APA StylePrice, S. J., Hughes, J. G., Jain, S., Kelly, C., Sederias, I., Cozzi, F. M., Fares, J., Li, Y., Kennedy, J. C., Mayrand, R., Wong, Q. H. W., Wan, Y., & Li, C. (2025). Precision Surgery for Glioblastomas. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(3), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15030096