Abstract

Polymer seals are utilized in various engineering applications to prevent leakage and contamination. The study investigates the wear and friction behavior of PTFE-based dynamic rotary seals, targeting their usage in space applications. Pin-on-disc dry sliding wear tests were performed with 0.5 MPa contact pressure and 0.2 m/s sliding velocity combining different lip seal (PTFE, PTFE+GF+MoS2), packing (PTFE, PTFE+Aramid fiber+solid lubricant) and shaft materials (34CrNiMo6, PEEK) involving third-body lunar (LHS-1) and Martian regolith (MGS-1) simulants. To understand the different influences of extraterrestrial regolith simulants compared to commonly encountered abrasives on Earth, quartz sand was selected as a reference. Quartz soil resulted in lower wear rates but a similar coefficient of friction to other regoliths. In the case of lip seals, testing with LHS-1 on PEEK and testing with MGS-1 on steel resulted in the most severe wear. Post-mortem surface analysis revealed the effect of external abrasive particles on the wear process and the transfer layer formation. The surface analysis confirmed that both lunar and Martian regolith simulants resulted in significant embedded particles. Based on the wear performance results, the lip seals performed better, but installation with an external packing could further aid the tribosystem.

1. Introduction

Machines utilize various types of seals or gaskets to prevent the leakage of lubricants or process fluids, whether gas or liquid. Specialized seals are used to maintain pressure or vacuum integrity, and they also play a critical role in protecting machinery from foreign particles that can cause operational downtime and failures. These particles may include hard, abrasive materials such as sand or, in aerospace applicants, lunar and Martian soil. Dynamic seals, designed to minimize leakage between moving surfaces, are categorized into linear reciprocating and rotating shaft types, e.g., lip seals, gland packings, and gaskets [1]. The required contact of the seals leads to reduced lifespan due to friction and wear. Adequate lubrication of dynamic contacting seals is essential, as well as a required surface finish of the shaft. The use of self-lubricating polymer seals, such as PTFE, eliminates the need for additional specific lubricants [2].

A lip seal, or radial shaft seal, is an elastomeric component sealing a rotating shaft by contact within a rigid housing, with its inner diameter slightly smaller than the shaft to create a sealing force [3]. Operating pressure enhances this force, and a garter spring can be added for demanding conditions. These seals range from simple, single-lip designs for standard applications to complex multi-lip configurations used in highly contaminated environments, such as in agriculture [4]. For high-temperature or high-pressure conditions (over 2 bar), lip seals are typically replaced by packings, consisting of braided cords pressed against the shaft by the stuffing box, often using lubricants like graphite or PTFE for durability [5,6]. In harsh environments, inadequate lubrication and high temperatures can accelerate the degradation and premature failure of elastomeric rotary shaft seals [7]. When such seals are insufficient, alternative materials must be considered. PTFE lip seals are commonly used in high-temperature, high-speed, and dry-run applications [8]. The disadvantage of PTFE is its low wear resistance, which can be improved with various fillers in different content, e.g., glass fibers, graphite, MoS2, etc. [9,10]. Previous research showed that PTFE filler content improves the wear resistance and the coefficient of friction (CoF) in polymer blends in abrasive environments [11].

The materials selected for this study are commonly used in sealing applications, including those targeted here. The seals currently used in the Mars Perseverance rover are spring-energized lip seals made of PTFE with additives such as graphite or glass fiber [12,13,14]. McCook et al. [15] performed sliding wear tests in a ball-on-disc configuration with 304 steel balls (X5CrNi18-10, EN 1.4301 [16]) inside a glove box that was continuously purged with extra-dry nitrogen. Discs composed of virgin PTFE and PTFE-PEEK composites were subjected to a normal load of 10N at sliding speeds of 0.1 and 0.4 m/s. It was found that the friction behavior of PTFE-based composites improves at cryogenic temperatures below −100 °C. Yuan and Yang [17] observed that the coefficient of friction of PTFE coatings slightly decreased under vacuum conditions while the wear resistance increased. They performed tests in ball-on-disc configuration under vacuum conditions, with GCr15 bearing steel balls (100Cr6, EN 1.3505 [16]) on LY12 aluminum discs with PTFE coating, with loads between 4 to 12 N and sliding velocities between 0.2 to 2.4 m/s for 1000 m sliding.

Delgado et al. [18] investigated spring-energized PTFE seals for their resistance to lunar regolith simulant infiltration. The tests were conducted in a vacuum chamber in dry condition, where the seals were mounted around a rotating shaft operating at 20 rpm. After 10,000 cycles, no external particle bypassed the seals, and minimal wear was observed on both the seals and the shaft. It was concluded that a spring-energized lip seal combined with extra sealing (e.g., wiper seal) could provide adequate protection against the ingress of external particles. Shen et al. [19] investigated the three-body abrasive wear of virgin PTFE using the pin-on-plate test setup (100 N normal load with 0.04 m/s sliding velocity) on a 316 L stainless steel counterpart introducing industrial-grade (5–250 μm) Al2O3 particles. The introduction of the hard third-body particles increased the coefficient of friction and wear of the steel counterface. However, the abrasive rate of the PTFE seal was reduced by the addition of abrasive particles.

PTFE-based composites show promising results for conditions encountered in aerospace applications [15,17]. However, studies by Mpagazehe et al. [20] on the abrasive effects of lunar regolith and Kalácska et al. [21] on the comparisons between different regolith types have highlighted a gap in knowledge. There are limited data on the tribological behavior of seals in lunar or Martian environments, where seals must resist the ingress of abrasive regolith simulants [22]. Further knowledge could be obtained on the effect of various three-body abrasive particles on PTFE-based composites.

This study aims to evaluate the tribological performance of PTFE-based rotary lip seals and gland packings with the addition of third-body extraterrestrial regolith simulants with shaft counterface materials, providing an initial screening of suitable materials. The primary function of the seals is to protect the shaft surface from the embedding of hard abrasive particles, which can damage both the seal and the shaft. Similar comprehensive tests utilizing specific lunar and Martian regolith simulants are not publicly available, and the available literature sources are limited. The objective is to understand the wear mechanism and the behavior of particle embedding to contribute to the development of sealing solutions for extraterrestrial applications, such as those used in probes, rovers, and robots. The wear and friction behavior of each tribosystem was assessed through active measurements and post-test analyses. Expected wear mechanisms, including three-body abrasion and adhesion, were thoroughly examined. Post-mortem surface analyses were conducted to investigate the transfer layer of PTFE on steel and PEEK counterfaces due to adhesion, as well as to analyze embedded particles in both the shaft and seal samples. The influence of different regolith types on these factors was also explored, and comparative analyses were performed. Additionally, the wear performance of lip seals versus packings was evaluated.

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Seal Materials

In the investigation, two lip seal materials and two packing materials were included. For the lip seal samples, 8 mm cubes were prepared. The first material was virgin PTFE (SKF Ecoflon 1). The second material was PTFE filled with 15 wt% glass fiber (GF) and 5 wt% molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) (SKF Ecoflon 2). PTFE+GF+MoS2 is commonly used for U-cups, glide rings, back-up rings, packings, and guide rings. The chemical resistance is similar to virgin PTFE, but the PTFE+15%GF+5%MoS2 composite has good physical properties and significantly better creep behavior [23]. Table 1 summarizes the most important characteristics of the seal materials.

Table 1.

Material properties of tested polymer seal (Ecoflon 1, 2) and counterface (Ecopaek) materials [23].

For the packing samples, 9 mm cubes were cut from commercially available packing cords manufactured by Chetra (Chetra Budapest Kft., Budakalász, Hungary). The first packing is a 100% PTFE packing seal (Chetra 1788), a chemically resistant packing seal for pumps, mixers, and valves [24]. The second packing is a hybrid composite of PTFE and aramid fibers, with the addition of lubricant-impregnated graphite (Chetra 1777 MS). This packing has high chemical resistance and good dry-running properties due to low friction. This material is typically used in centrifugal pumps, mixers, and valves in areas such as the (petro)chemical industry, food industry, and wastewater treatment [25]. Table 2 contains the material properties of the packings.

Table 2.

Material properties of tested packing materials [24,25].

2.2. Counterface (Shaft) Materials

Two shaft materials were selected for the counterface discs. The first material is low-alloyed tempering steel, 34CrNiMo6 (EN 1.6582 [16]). This material is turned from a 50 mm rod to discs with a thickness of 5 mm. This material has a high tensile strength (~1000 MPa), hardness (360 HB), and good fatigue resistance (140 J, 20 °C ISO V 148-1:2006 [26]) and is commonly used in machine construction and the automotive industry for components such as shafts and gears [27].

The other counterface material is polyetheretherketone (PEEK) (SKF Ecopaek); the material properties are included in Table 1. PEEK is an ultra-high-performance polymer with high tensile strength, stiffness, high heat distortion temperature, and good sliding and friction properties [23].

2.3. Thrird-Body Abrasives

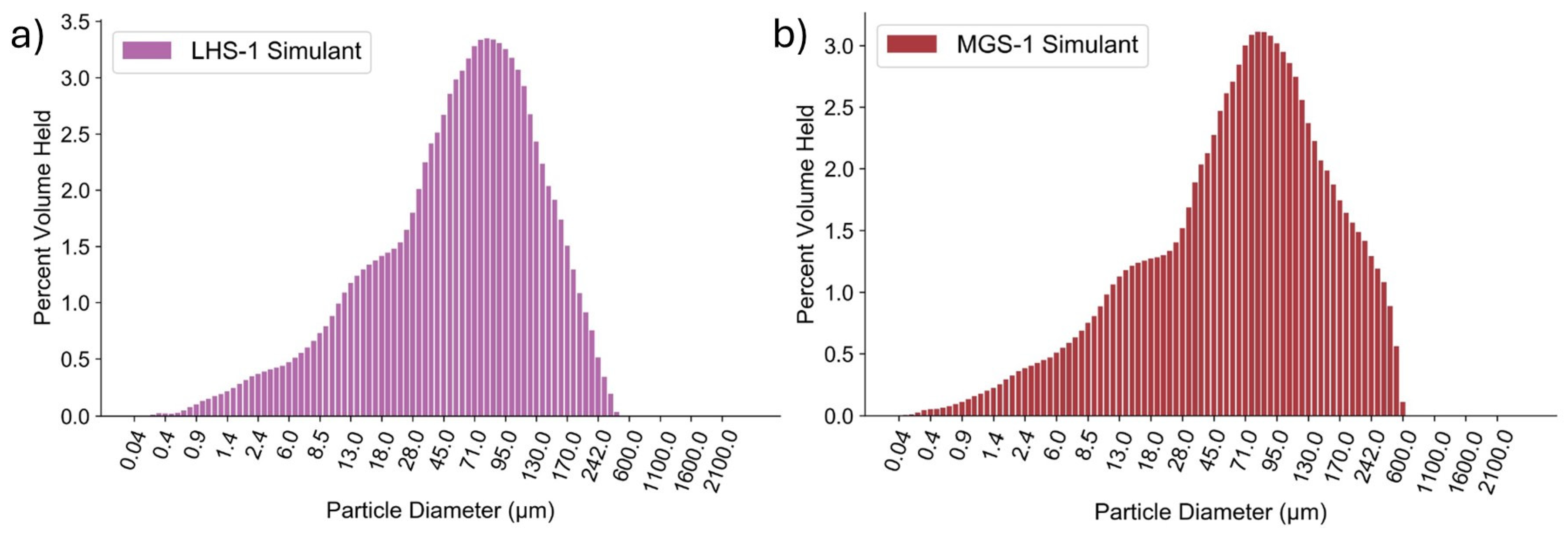

Three different external abrasives were selected for the three-body abrasion tests. Two regolith simulants correspond to lunar and Martian extraterrestrial soils. The first is the Lunar Highland Simulant (LHS-1) regolith. The mineralogy of this simulant is mainly anorthosite (74.4 wt%) and glass-rich basalt (24.7 wt%) [22]. The particle size (diameter) is shown as a function of the percent volume held in Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Particle diameter distribution in function of volume of (a) Lunar Highland regolith simulant [28] and (b) Mart Global regolith simulant [29].

The second regolith is Mars Global Simulant (MGS-1). This simulant is more mixed, with a mineral composition of anorthosite (27.1 wt%), glass-rich basalt (22.9 wt%), pyroxene (20.3 wt%), and olivine (13.7 wt%) [22]. The particle size (diameter) is shown as a function of the percent volume held in Figure 1b).

To understand the different influences of extraterrestrial regolith simulants compared to commonly encountered abrasives on Earth, quartz sand was selected as a reference. N°1 Quartz F46 (0.1–0.5 mm) was provided by Euroquartz (Euroquartz NV, Hermalle-Sous-Argenteau, Belgium). The main mineral of this soil is quartz, and the chemical composition consists mainly of silica (>96 wt%), providing 7 Mohs hardness with naturally rounded, irregular particles. The bulk chemistry and basic characteristics of the tested external particles are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Bulk chemical composition and characteristics of abrasive particles [28,29,30].

2.4. Test Methodology

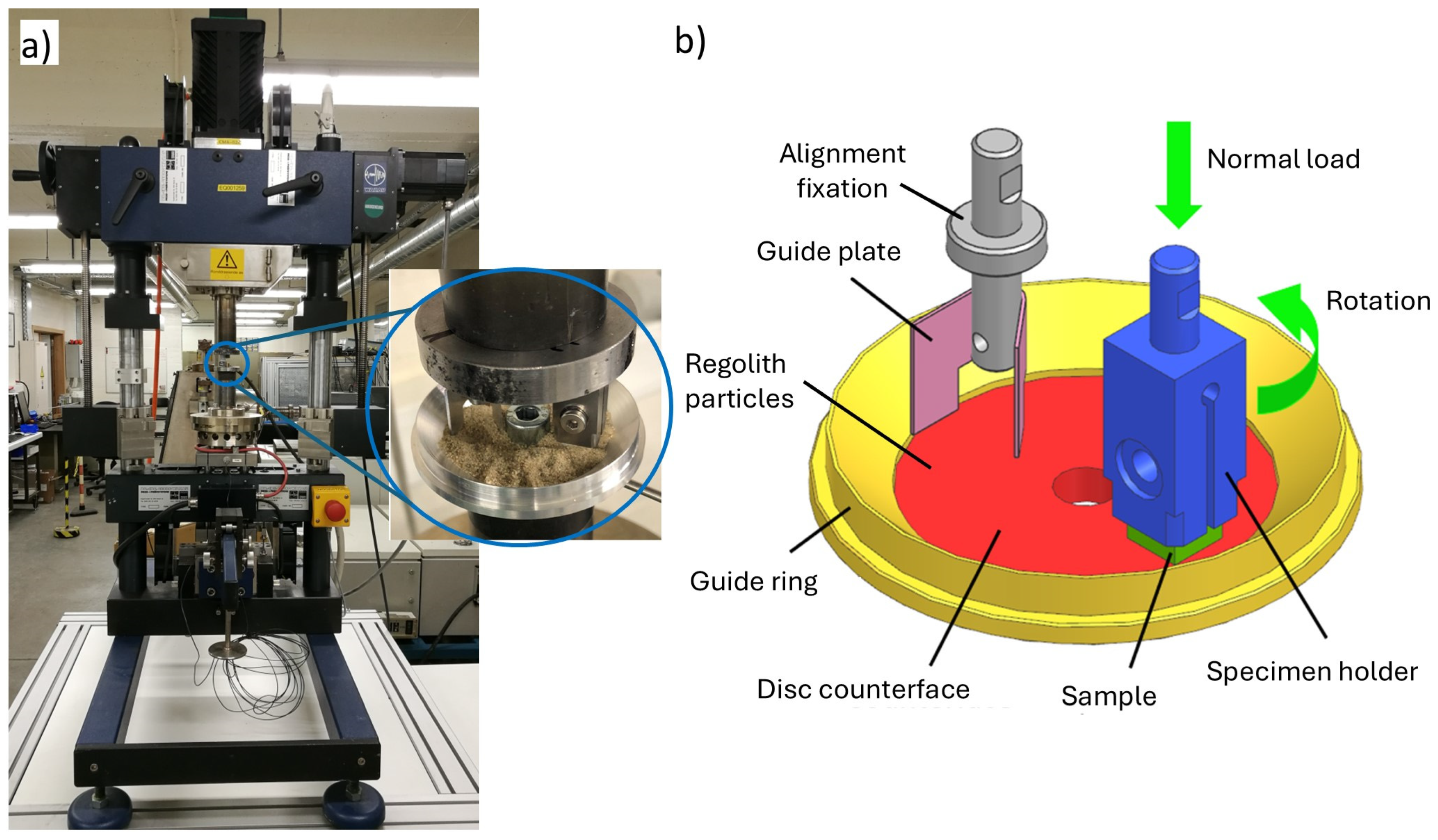

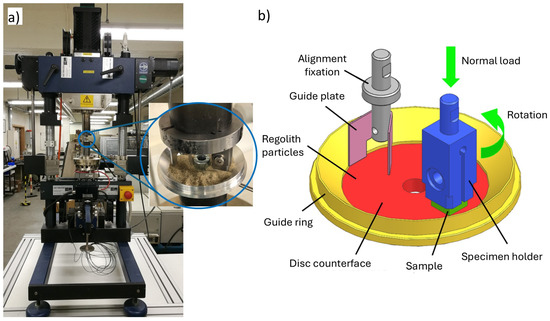

The experiments were performed with a Wazau TRM 1000 tribometer using a pin-on-disc configuration. The fixed cubic polymer samples were rotated on a radius of 15 mm on the stationary counterface disc with a diameter of 50 mm, resulting in a wear track centreline diameter of 30 mm. The pin specimen did not rotate around its own axis. Different regoliths were introduced to investigate three-body abrasion of the samples. The used test setup is shown in Figure 2a, and the 3D contact model with the main machine parts can be seen in Figure 2b. The guide ring served to keep the abrasive particles on top of the counterface, while the guide plate ensured the pushing of the fresh regolith in the rotation path of the specimen. The regolith volume was equal among the tests. The bulk temperature of the counterface below the contact was measured under the counterface (5 mm) using a thermocouple. The counterface discs were characterized by an average surface roughness (Ra) of 1.0 ± 0.1 μm. The grinding of the counterface disc was performed in a spiral pattern so that the polymer sample slid over the counterface along the direction of the grooves. This simulates a seal radially sliding over a rotating shaft. The surface roughness of the discs was measured with a Hommel Tester T1000 (Viernheim, Germany), type 240853.

Figure 2.

(a) Test setup and (b) model of pin-on-disc assembly with the installed regolith guide plates and ring.

The mass of the pin samples was registered with Ohaus AX324 (Parsippany, NJ, USA) with 0.0001 g resolution before and after the wear tests. To eliminate the presence of the not embedded, loose external particles from the pin specimen surface, the worn samples were wiped with a soft brush and with the help of pressurized air. The polymer samples were conditioned before and after the wear tests at room temperature and RH 45 ± 0.3% for 48 h. The height reduction was also tracked with a digital caliper with 0.01 mm resolution. Before each wear test, the polymer materials were cleaned with isopropanol, while the steel counterfaces were wiped with acetone and then isopropanol. At the start of the test, the pin specimen was lowered on top of the counterface, after which the external particles were introduced and uniformly spread along the surface of the counterface. All machine parts (guide ring, plates, sample holders, etc.) were thoroughly cleaned with isopropanol after each test to ensure no particle contamination from the different external particles. Each test was repeated three times. The test conditions were selected to resemble operational conditions documented for Martian and lunar rovers, such as the Perseverance rover, which uses similar dynamic rotary seals [12,13,14]. The force exerted by a spring-energized seal against the shaft under low atmospheric pressures is primarily determined by the spring load, typically ranging from 1 to 50 N. For an NBR spring-energized lip seal with a nominal shaft diameter of 70 mm, an estimated contact force of 32 N is reported by Stakenborg [31], which values appear consistent with the test result reported by Shen et al. [19] and Huang et al. [32]. The lip seal specimens were tested with 0.5 MPa contact pressure, corresponding to 25 N load and 0.2 m/s sliding speed. For the packings, the load was reduced to 0.2 MPa. The sliding distance was set to 500 m; however, two PTFE+AF packing specimens were torn apart in the first few initial meters (PTFE+AF packings on 34CrNiMo6 with MGS-1 soil and PTFE+AF packings on PEEK with LHS-1 soil). These specimens are considered failed and not suitable for the applied tribosystem. Surface roughness and topography analyses, both pre-test and post-mortem, were performed using a Keyence VR-5200 (Osaka, Japan) wide-area 3D measurement system.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Wear Investigation

3.1.1. Lip Seal Specimen

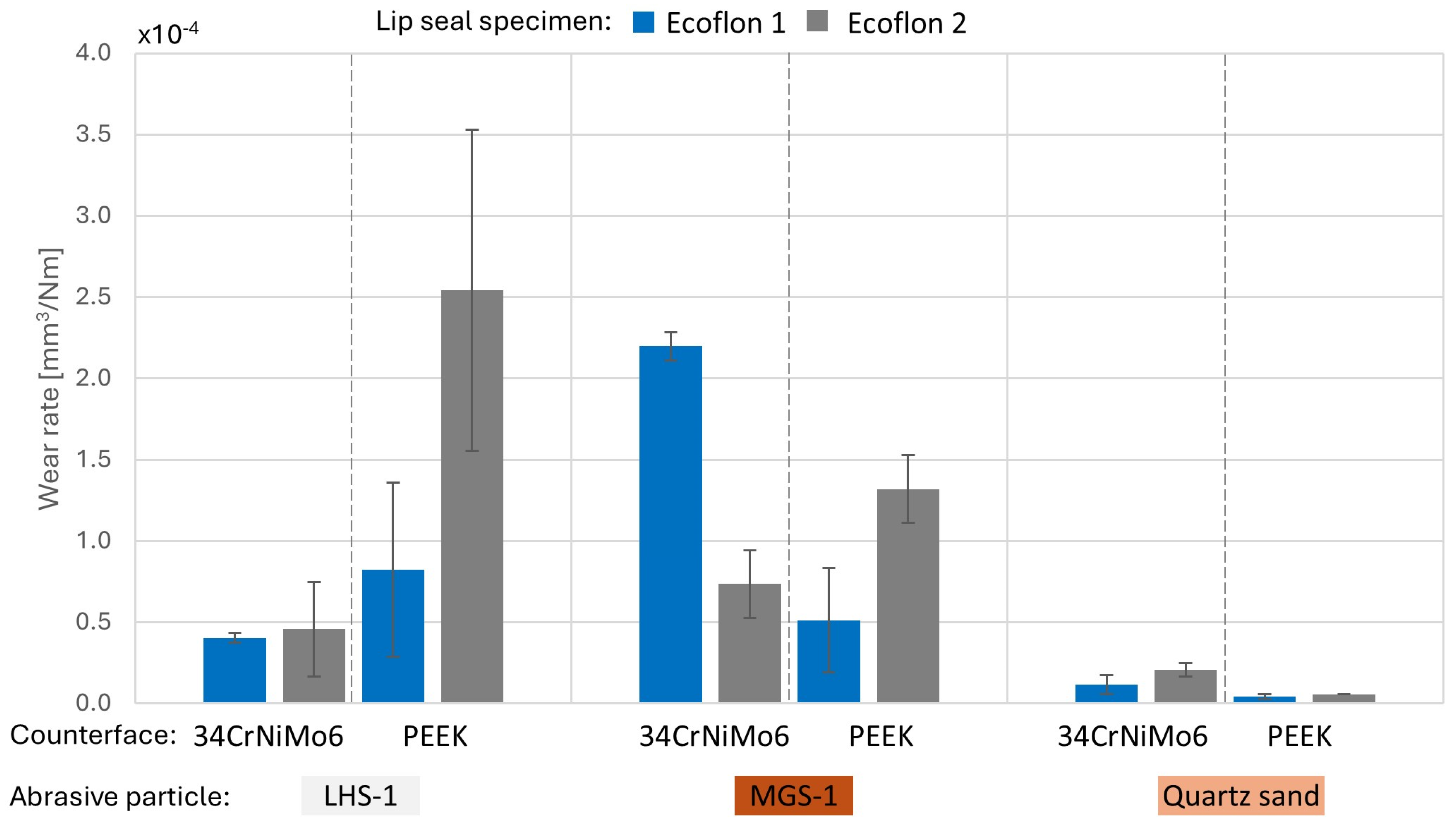

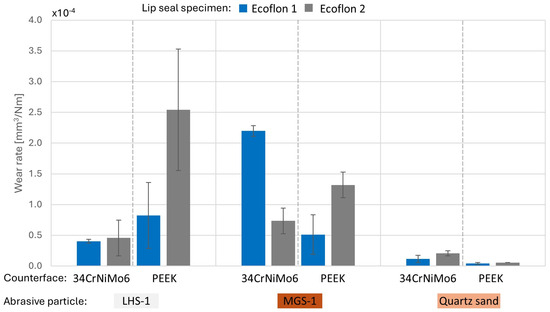

Due to the weight of the embedded particles in the polymer sample adding to the total measured mass, the mass loss does not give an accurate representation of the wear rate. In the wear test, results not only from the material loss from the specimen but also the gain from the embedded particles are evaluated together. The specific wear rate of polymers was calculated by dividing the measured mass loss by the density of the polymer, with the applied normal load and the sliding distance. The results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Wear rate [mm3/Nm] of tested lip seal materials.

Similar to the research by Amenta et al. [33] in the case of two-body abrasion tribosystems, the wear rate of the reinforced PTFE is above the neat PTFE. However, when testing on the steel counterface with Martian regolith, this was not the case. LHS-1 and MGS-1 regoliths have a more significant impact on the wear rate of PTFE-based materials than the reference quartz sand. PEEK counterface seemed to cause more wear on the seal specimen than 34CrNiMo6. It could be possibly explained by the more pronounced regolith particle embedding in the softer counterface, acting as a two-body system. It was confirmed from the visual inspection of the counterfaces that the PEEK was more covered with embedded regolith particles. Furthermore, in the case of PEEK, adhesion also contributes to the wear process, further degrading the seal material. Although it would result in a more prevalent tribo-layer, it is damaged by the third-body abrasive particles, and the beneficiary effects are mitigated.

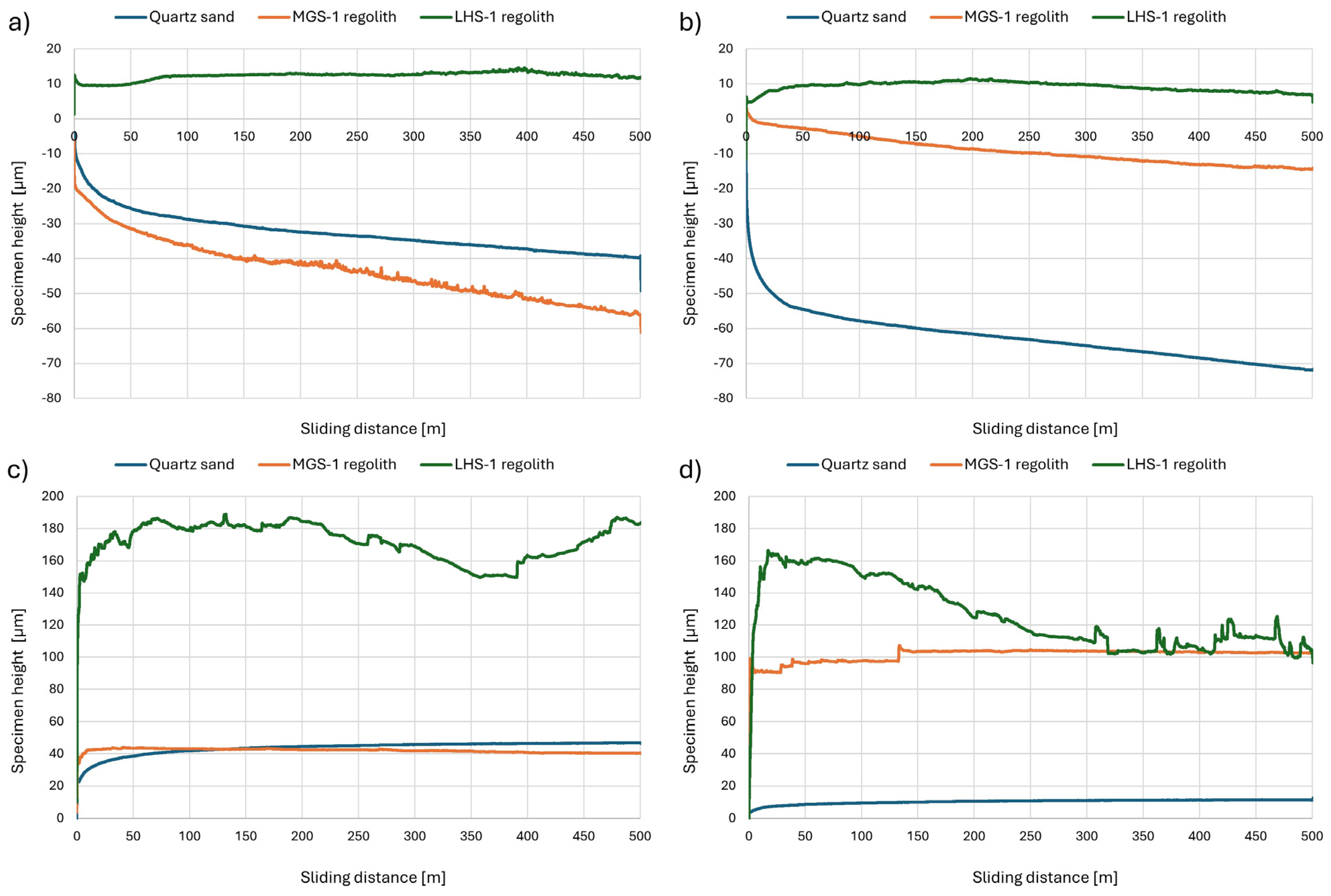

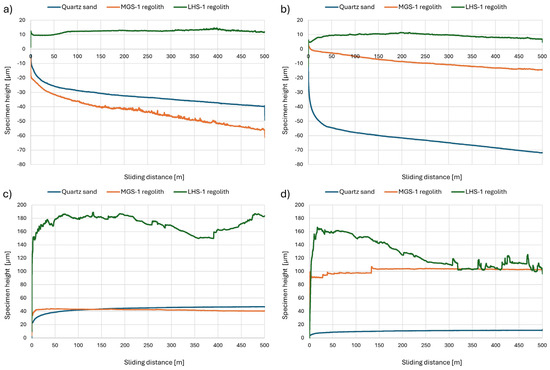

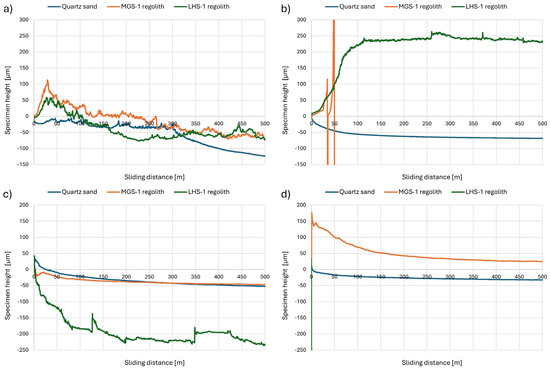

The specimen height was continuously registered during the sliding. Figure 4 shows the different test cases. The specimen height is not only influenced by the wear of the sample but also by the infiltrated and embedded third-body particles, as well as the formed tribo-layer on the counterface.

Figure 4.

Effect of external abrasive particles on the wear of lip seal specimens. (a) PTFE on 34CrNiMo6 counterface, (b) PTFE+GF+MoS2 on 34CrNiMo6 counterface, (c) PTFE on PEEK counterface, and (d) PTFE+GF+MoS2 on PEEK counterface.

The initial height increase at the start of the tests was the highest (~10–180 µm) in the case of the LHS-1 regolith, suggesting that the specimen was running on a layer of particles. The quartz sand had a reduced effect on the initial run setting. Not only the particle size and angularity are responsible for this, but also the packing density of the external regolith. In the case of the steel counterface tests, a clear decreasing trend could be established for the seal specimen height with increasing sliding distance.

For the PEEK counterfaces, the trend is not so straightforward due to the additional adhesion mechanism, e.g., in the case of LHS-1 regolith on PEEK with PTFE seal specimen, around ~380 m, the specimen height starts to increase. This could be attributed to the dynamic three-body mechanism, with a balance of constant adhering transfer layer formation with particle embedding compensated with wear and tear-off of the layer. In the case of lunar regolith and steel counterface, the general three-body abrasion process was observed on a smaller scale. The process starts with a short running-in period of ~10–20 m, where the micro geometry of the softer specimen is transformed, and the roughness peaks are adjusted. The third-body particles enter the contact zone, leading to an increase in wear (displacement between counterface and pin sample). This converges into a dynamic process, a cyclic equilibrium state (steady state). The particles slide and roll between the contacting surfaces and may get embedded. Then, they abrade the surface material to the point where it breaks apart, allowing new particles to enter the contact zone and embed again.

In the case of Martian regolith, the wear does not increase substantially before decreasing again, as with the LHS-1 particles. Rather, it displays a logarithmic decreasing trend. After the running-in period, a tribofilm is formed, decreasing the wear rate. The formed tribo-layer lowers the wear rate by reducing direct contact between the pin and counterface by protecting the polymer from the counterface asperities [34]. The transfer layer is formed during the running-in phase by depositing polymer material in the roughness valleys of the counterface. Hence, the contact transitions from a polymer/steel contact to a polymer/partial polymer/partial steel contact. Research shows that MoS2 as a filler has a beneficial effect on the formation and durability of the transfer layer [35,36], which could be confirmed by comparing the results of neat PTFE with MGS-1 on steel counterface (Figure 4a) and with PTFE+GF+MoS2 specimen with MGS-1 on steel counterface (Figure 4b).

When investigating the tests on the PEEK counterface with lunar/Martian regolith, the increase in specimen height is more significant than with a steel counterface. This shows that the PEEK countersurface allowed particles to enter the contact zone, which embeds more easily in the PEEK surface than in steel, making it easier to embed in the pin samples. As a result, a thicker regolith layer lifts the pin from the PEEK disc more permanently than on the steel surface.

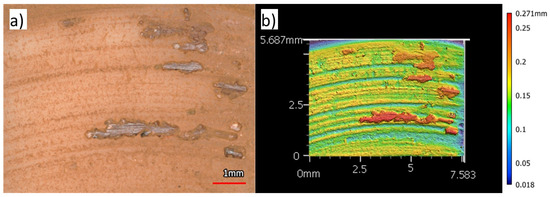

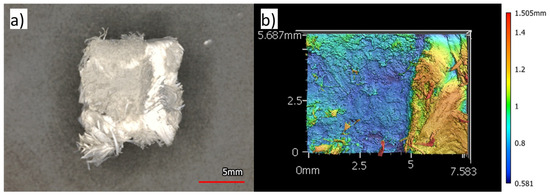

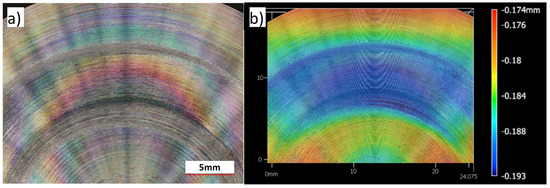

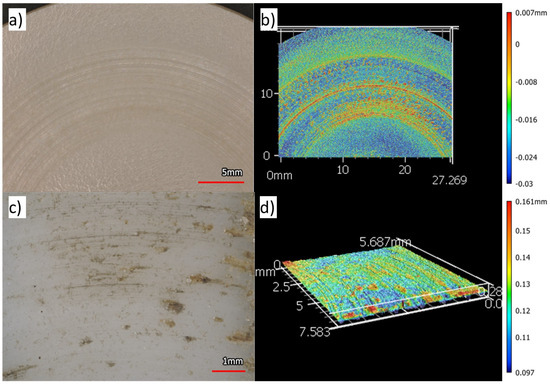

Figure 5 shows an example of the Martian regolith-covered PTFE seal surface, indicating a formed transfer layer, as well as embedded external particle agglomerates.

Figure 5.

(a) Optical microscopy and (b) 3D topography of PTFE lip seal sample tested on PEEK with MGS-1 regolith.

3.1.2. Wear of Packings

The packings have an uneven surface topography, which allows particles to be easily introduced in the contact zone, and this could explain the experienced fluctuations in the wear graphs. The trapped particles contribute to the increased mass of the samples after the test. For this reason, the wear rate is not representative of the wear of the PTFE and PTFE+AF packings and will not be taken into account. A wear analysis will be based on the online registered height of the specimen and the post-test surface analysis.

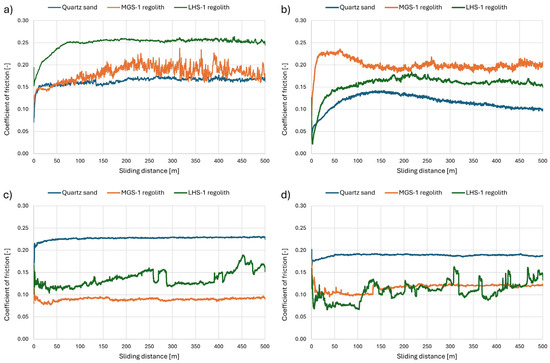

Figure 6 shows the effect of external abrasive particles on the wear of packing specimens. The wear of the packing samples on steel counterfaces (Figure 6a,b) varies more compared to the lip seal samples in Figure 4. The range of height loss extends from 20–60 µm for lip seal to 250–400 µm for packing materials. Some graphs show a sudden increase/decrease in the specimen height, indicating a sudden layer removal from the packing due to abrasion. An example of this is visible in the case of neat PTFE packing tests on steel counterface with quartz particles (Figure 6a), where a sudden drop in specimen height occurred at ~300 m sliding distance, indicating loss of material. It could be linked to the partial removal of the top layer of the packing sample, as shown in Figure 7. Also, the dislocated fibers might roll under the packing sample, causing the registered height to rise. When the fibers and soil particles are removed from the contacting area, the packing sample height lowers again.

Figure 6.

Effect of external abrasive particles on the wear of packing specimens. (a) PTFE on 34CrNiMo6 counterface, (b) PTFE+AF on 34CrNiMo6 counterface, (c) PTFE on PEEK counterface, and (d) PTFE+AF on PEEK counterface.

Figure 7.

(a) Optical image and (b) 3D topography of the partially removed surface layer of a pure PTFE packing sample tested on 34CrNiMo6 steel with quartz sand.

The data from the PTFE+AF specimen tested on steel with MGS-1 regolith and the PTFE+AF specimen tested on PEEK with LHS-1 are incomplete. The tests have been attempted more than three times, but the specimen was always torn apart immediately after start or after reaching a maximum of ~30–50 m sliding; therefore, these packing seal materials are not considered suitable for Martian or lunar conditions. The data are shown until the point of failure indicated by a sudden drop of >1000 µm in the specimen height. The lines show an increase in displacement just before the point of failure, suggesting that many particles were suddenly introduced in the contact zone. This led to an increase in the CoF and, ultimately, the failure of the pin sample with a torn top layer. The term failure rather than the wear of the two packing specimens gives a more accurate approach to the nature of the failure. When comparing the braided structure of natural PTFE with its composite version, it was observed that the disintegration and slipping of the braided fibers in the composite specimens occurred more rapidly. This accelerated degradation is attributed to the impregnation of the composite fibers with a mixture of solid lubricant and wax, which reduced inter-fiber friction compared to natural PTFE fibers. The enhanced sliding behavior of the composite resulted in an increased specific surface area, facilitating the accumulation of regolith within the impregnated lubricant.

Figure 6c,d indicate the result with the PEEK counterface. Similar to the conclusion concerning the range of the height loss in the case of steel counterface, testing on PEEK resulted in more broad values compared to the lip seal specimen. The range increases from 100–200 µm to 250–400 µm for the lip seals and packing samples, respectively. When testing PTFE+AF with MGS-1 on the PEEK counterface, the particles were immediately introduced in the contact area at the start of the test, increasing the height (wear) displacement to ~180 µm. In general, LHS-1 regolith caused more fluctuations and particle embedding (Figure 6b) or wear (Figure 6c) than other external particles.

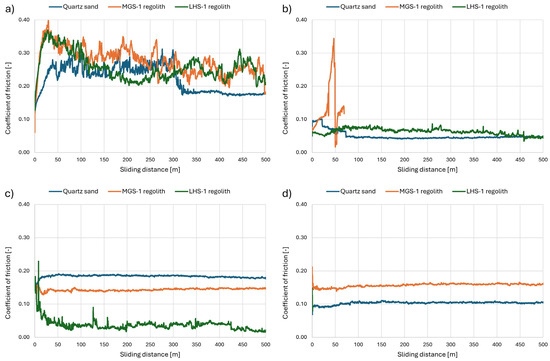

3.2. Friction Analysis

Figure 8 shows the influence of external abrasive particles on the coefficient of friction of the lip seal specimen. The friction curves showcase the main friction components: adhesion and surface deformation, which are influenced by the embedding and erratic movement of regolith particles. These effects vary according to the properties of the contacting surfaces and the tribological system. This complex third-body phenomenon has been extensively described in the literature [37]. In the initial stages of the sliding in all test systems, during the running-in, the regolith particles enter the contact zone with varying dynamics. Subsequently, a macro-trend emerges, representing the dynamic equilibrium of friction. This equilibrium is characterized by localized transient behaviors influenced by the specific attributes of the tribological system. On steel surfaces, quartz sand resulted in a relatively uniform third-body mechanism. The distinct compositions and adhesion characteristics of LHS-1 and MGS-1 regoliths led to contrasting friction patterns between the natural and composite PTFE lip seal specimens. The lower grain-embedding capability of the harder composite PTFE resulted in more consistent friction with MGS-1 regolith compared to natural PTFE pin. In the case of the PEEK countersurface, the higher adhesion tendency between the polymers prevailed, particularly in the presence of quartz sand, while in the case of LHS-1, the process was characterized by friction instability.

Figure 8.

Effect of external abrasive particles on the coefficient of friction of lip seal specimens. (a) PTFE on 34CrNiMo6 counterface, (b) PTFE+GF+MoS2 on 34CrNiMo6 counterface, (c) PTFE on PEEK counterface, and (d) PTFE+GF+MoS2 on PEEK counterface.

Figure 9 shows the effect of external abrasive particles on the coefficient of friction for packing specimens. The tests with packing specimens were only partially suitable for studying friction differences since the structural integrity of the braided structure is broken during sliding. Unlike the block sealing material tests, these experiments were influenced by the complex, inhomogeneous 3D surface formed by the woven fibers. These fibers, with micro- and macro-grooves, deform differently under normal loads depending on whether they are natural or composite PTFE braids. The gaps between the fibers act as localized traps, effectively retaining regolith particles and slowing their movement through the contact zone, similar to the principle of a labyrinth seal. While beneficial for sealing purposes, these trapped abrasive particles intensify countersurface cutting and friction instability, depending on the type of regolith. Figure 9a,c illustrate these phenomena, which are particularly pronounced with natural PTFE braided pins on PEEK surfaces when LHS-1 regolith was applied. On the steel surfaces, the integrity of the composite packing pins was prematurely lost due to the fiber separation, preventing the completion of the measurements.

Figure 9.

Effect of external abrasive particles on the coefficient of friction of packing specimens. (a) PTFE on 34CrNiMo6 counterface, (b) PTFE+AF on 34CrNiMo6 counterface, (c) PTFE on PEEK counterface, and (d) PTFE+AF on PEEK counterface.

3.3. Surface Analysis

The post-mortem 3D topography analysis revealed a reduction in surface height within the wear track of the counterface disc materials attributed to abrasion caused by the polymer sample with the external particles. An example is shown in Figure 10, where the blue region represents the wear track with reduced surface height.

Figure 10.

Post-mortem (a) macro image and (b) 3D surface topography of 34CrNiMo6 steel counterface tested in PTFE+GF+MoS2 with LHS-1 regolith tribosystem.

The scale bar in the 3D images highlights the difference in height between the wear track and the unaffected surface. Across all steel counterfaces, the lip seal samples resulted in a surface height reduction of approximately 0.01 to 0.02 mm, regardless of the regolith type. In comparison, the packings caused a larger reduction between 0.02 and 0.03 mm. Within the wear track, the average surface roughness of Ra of the steel counterfaces also decreased by approximately 0.1 µm. Abrasion likely removed the roughness peaks, smoothing the surface and lowering roughness compared to the unaffected areas. Furthermore, adhesion may have facilitated the formation of a polymer transfer layer on the steel counterface, with possible compaction of regolith particles deposited in surface valleys. The reduction of ~25% in the mean roughness depth (Rz) values on the steel surfaces indicates this phenomenon. For the steel counterfaces, the wear tests produced an evenly distributed wear track with no distinct grooves or peaks. Both lip seal and packing samples exhibited minimal transfer layers. No significant differences were observed between the pure PTFE and PTFE+GF+MoS2 lip seal samples or between the pure PTFE and PTFE+AF packing samples. The observed visible discoloration of the wear track is likely due to the adhesion of regolith particles, as the color of the wear tracks closely matched that of the respective regoliths. This effect was more noticeable on PEEK counterfaces than on steel. While the steel counterfaces showed limited wear, the pin samples, especially the lip seal samples, displayed clear signs of abrasion (Figure 11).

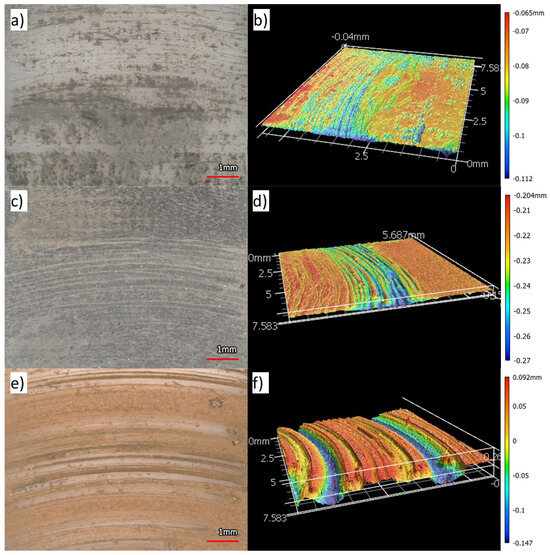

Figure 11.

Post-mortem optical microscopy and corresponding 3D topography of tested pin specimens. (a,b) PTFE on steel counterface with quartz sand, (c,d) PTFE+GF+MoS2 on steel counterface with LHS-1 lunar regolith, and (e,f) PTFE on steel counterface with MGS-1 regolith.

The steel counterfaces showed no clear evidence of embedded particles, regardless of regolith or seal material. As the PTFE lip seal samples are softer, hard particles tend to create grooves or are embedded in the lip seal surface rather than in the steel. This caused significant wear on the lip seal surface with visible grooves, adhesion of small dust particles, and embedding of larger particles. Quartz soil caused only minor abrasion and adhesion on the lip seal samples, resulting in slight scratches and discoloration. Lunar regolith produced deeper grooves and small embedded particles on the lip seal surface. The Martian regolith resulted in the most severe effect, with large cuts and visible embedded particles on the lip seal surface (Figure 11).

The PEEK counterface was more susceptible to abrasion than steel. Embedded particles and adhesion of smaller dust particles were observed. Moreover, PEEK had a notable impact on the embedding of abrasive particles in the lip seal surfaces. Larger particles from lunar and Martian regoliths were often embedded in the lip seal samples, as shown in Figure 12 and Figure 13. The PTFE+GF+MoS2 composite displayed larger embedded particles than pure PTFE. The PTFE/PEEK sliding tests clearly demonstrated the three-body abrasion mechanism, where abrasive particles penetrated the lip seal surface and subsequently cut into the PEEK surface. Unlike steel, the PEEK surface exhibited signs of embedded and adhered quartz soil particles.

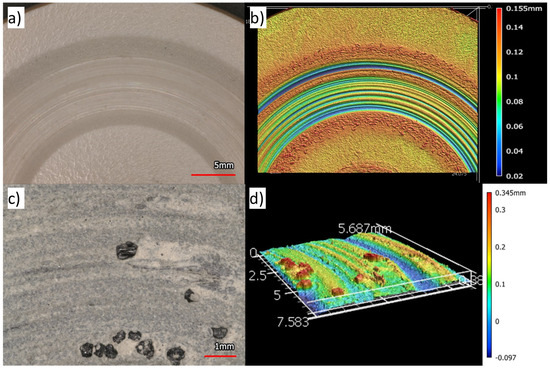

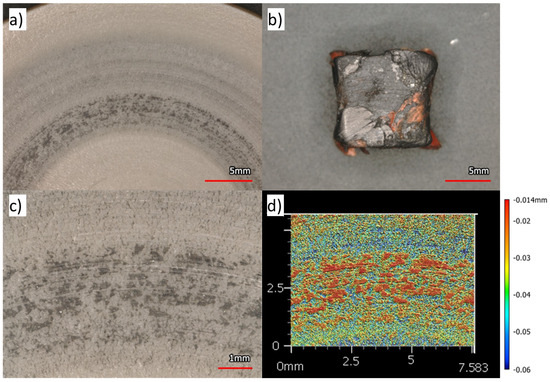

Figure 12.

Post-mortem (a) macro image and (b) 3D surface topography of PEEK counterface tested in PTFE+GF+MoS2 with LHS-1 regolith tribosystem and the embedded LHS-1 particles in the PTFE+GF+MoS2 pin: (c) optical image and (d) 3D topography.

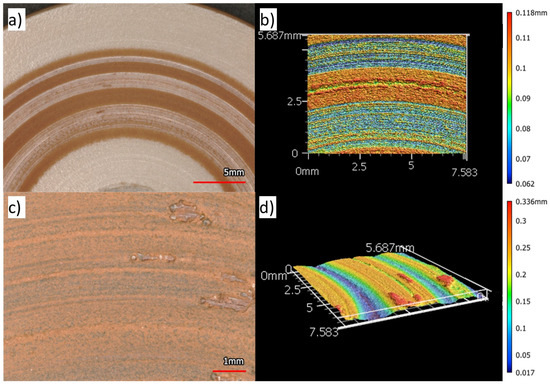

Figure 13.

Post-mortem (a) macro image and (b) 3D surface topography of PEEK counterface tested in PTFE+GF+MoS2 with MGS-1 regolith tribosystem and the embedded MGS-1 particles in the PTFE+GF+MoS2 pin: (c) optical image and (d) 3D topography.

Figure 12a,b show the combined effects of abrasion and adhesion within the wear track on a PEEK counterface tested with PTFE+GF+MoS2 with LHS-1 regolith. Abrasion had a more pronounced impact on the PEEK counterface material due to its lower hardness compared to 34CrNiMo6 steel. Clear, distinct grooves could be identified on the pin surface, formed by harder lunar regolith particles embedded in the PTFE composite pin, as shown in Figure 12c,d.

The abrasion and adhesion zones on PEEK counterfaces were more pronounced in the case of the PTFE+GF+MoS2 lip seal samples tested with Martian regolith, as shown in Figure 13a,b. Hard abrasive particles penetrated the surface of the PTFE composite more easily than the virgin PTFE lip seal samples when sliding on the PEEK counterface, regardless of the regolith type. The surface of the PTFE+GF+MoS2 pin is shown in Figure 13c,d.

The Martian regolith caused limited embedding of hard particles on the PEEK surface, as the larger particles were primarily embedded in the lip seal samples. This resulted in an uneven surface, with distinct zones of abrasion and adhesion on the PEEK counterface. The adhesive zones had smooth surfaces with no embedded particles, whereas the abrasive zones on the PEEK surface contained embedded hard particles. The opposite was true for the lunar regolith, where the adhesive zones along the edges of the wear track had a higher concentration of embedded particles (discoloration in optical images) compared to the abrasive zones in the center of the wear track. The extraterrestrial regolith particles were embedded in the lip seal surface, creating grooves in the PEEK counterface. The edges of the lip seal samples were also worn off. 3D surface topography of PEEK counterface tested with PTFE and quartz sand and the embedded several quartz particles in the PTFE pin are highlighted in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Post-mortem (a) macro image and (b) 3D surface topography of PEEK counterface tested with PTFE and quartz sand and the embedded several quartz particles in the PTFE pin: (c) optical image and (d) 3D topography.

The packing samples caused similar effects on the PEEK counterface as on the steel surfaces. Regolith particle adhesion to the PEEK surface was less significant with packing samples. The transfer layer was minimal, and no significant roughness peaks or valleys formed due to abrasion or adhesion. Only the PTFE+AF/PEEK/Quartz tribosystem showed clear graphite adhesion on the PEEK surface, as shown in Figure 15. The packing samples did not produce significant grooves on the PEEK surface. This indicates that while particles entered the packing/PEEK contact zone more easily, they did not penetrate deeply enough to form grooves on either surface. The packing samples seemed to provide some protection to both the PEEK and steel shaft surfaces from abrasion and particle embedding. However, the packing material itself showed limited wear resistance, as evident from clear signs of layer removal and fiber detachment.

Figure 15.

(a) Macro image of PEEK counterface, (b) macro image of PTFE+AF packing sample, (c) optical microscopy, and (d) 3D topography of the wear track on PEEK tested with quartz.

The results further highlight the benefit of incorporating external packing materials in the tribosystem. Overall, the wear behavior of the seals was significantly influenced by the material composition and environmental conditions. PTFE filled with 15 wt% glass fiber and 5 wt% molybdenum disulfide (PTFE+GF+MoS2) enhances wear resistance and reduces friction compared to unfilled PTFE under similar abrasive conditions. PEEK counterfaces exhibited greater susceptibility to embedded particles, facilitating three-body abrasion mechanisms. The inclusion of fillers, e.g., glass fiber in PTFE, was observed to improve the formation of protective tribo-layers, mitigating direct material loss and enhancing durability under dynamic contact conditions. The effect of the specific abrasive environment is further investigated. The quartz sand, characterized by its larger particle size, caused increased vibrations during sliding but resulted in minimal particle embedding. Its spherical shape particles likely rolled between the surfaces, reducing wear and penetration. Neither steel nor PEEK counterfaces showed significant grooves or particle embedding, and the wear rates for both seals were the lowest among all tested conditions.

The LHS-1 regolith exhibited greater adhesion than quartz, causing dust to adhere to surfaces and particles to embed in lip seals and PEEK counterfaces. This led to the formation of grooves and higher material removal, particularly on PEEK, which, combined with lunar regolith, resulted in the highest wear rate for the PTFE+GF+MoS2 samples. Steel counterfaces, in contrast, had relatively low wear rates. An adhesive layer formed at the edges of the wear tracks in lip seal tests, with less pronounced effects in packings.

The Martian MGS-1 regolith was the most adhesive, causing significant adhesion on both counterfaces and seals. Particle embedding was more prominent in lip seals than packings. Steel counterfaces showed minimal effects, while PEEK had uneven zones with distinct areas of abrasion and adhesion. MGS-1 regolith caused the highest wear rates for pure PTFE lip seals sliding on steel. The CoF was similarly influenced by the lunar and Martian regolith.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the wear and friction performance of PTFE-based lip seals and packings for potential use in extraterrestrial applications (e.g., rovers), focusing on combinations of different seal materials, shaft materials, and abrasive particles. The specific wear rate and coefficient of friction (CoF) were found to be highly dependent on the tribosystem.

The steel counterfaces showed minimal wear and no significant embedding of particles across all tested conditions. Hard particles tended to create grooves or embed in the softer PTFE lip seal surfaces, particularly with lunar and Martian regoliths, which caused increased wear and visible abrasion. Quartz soil caused only minor abrasion and adhesion, resulting in the lowest wear rates among all tribosystems. Its larger, spherical particles rolled between surfaces rather than penetrating them, contributing to minimal embedding or damage.

PEEK counterfaces were more prone to abrasion and embedding compared to steel. Abrasive particles from lunar and Martian regoliths are frequently embedded in the lip seals and occasionally cut into the PEEK surface, highlighting a clear three-body abrasion mechanism. Martian regolith was found to be the most adhesive, causing substantial adhesion on both PEEK and polymer surfaces, leading to uneven wear zones on PEEK with distinct regions of abrasion and adhesion. Lunar regolith exhibited higher particle stickiness than quartz and created grooves and embedded particles in lip seal surfaces. While Martian regolith led to higher wear rates for pure PTFE lip seals sliding on steel, lunar particles caused a significant increase in wear rates on PEEK counterfaces, with adhesive zones forming along the edges of the wear tracks.

The friction behavior of lip seals stabilized after a running-in period of approximately 100 m of sliding. Steel counterfaces produced higher coefficients of friction with lunar and Martian regoliths (0.17–0.25) compared to PEEK (0.10–0.14). Quartz soil resulted in the lowest CoF and wear rates for all combinations.

Packing samples exhibited limited particle embedding, as embedded particles were typically removed along with the outer fiber layer during wear. Packing samples also displayed fluctuating friction due to their uneven surface structure and layer detachment. However, they provided additional protection to counterfaces, reducing overall particle intrusion and wear.

The wear rates observed in this study were strongly dependent on the tribosystem. While quartz soil posed minimal abrasive challenges, the introduced extraterrestrial lunar and Martian regoliths led to higher wear rates (~100–450%). These findings highlight the importance of selecting tribosystem components based on the specific abrasive environment. The combination of lip seals and external packings could enhance tribosystem performance by mitigating particle intrusion and protecting counterfaces from excessive wear, particularly in extraterrestrial applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Á.K. and G.K.; methodology: Á.K. and A.C.; software: J.C.P. and A.C.; investigation: A.C. and Á.K.; data curation: A.C. and J.C.P.; writing—original draft preparation: Á.K. and A.C.; writing—review and editing: G.K. and P.D.B.; supervision: P.D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from the first/corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Barkó György for providing the regolith materials and Róbert Keresztes and Tonino Vandecastele for their support in the preparation of the test specimens.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nikas, G.K. Friction and Wear of Seals. In Friction, Lubrication, and Wear Technology; ASM International: Almere, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, F.; Haas, W. A New Approach to Analyze the Hydrodynamic Flow in Sealing Aids—PTFE-Lip Seals with Spiral Grooves. Tribol. Trans. 2007, 50, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Shevchenko, S.; Radchenko, M.; Shevchenko, O.; Radchenko, A. Methodology of Designing Sealing Systems for Highly Loaded Rotary Machines. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Hu, J. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Study on Sealing Performance and Frictional Property of Rotary Lip Seal. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 2021, 9922521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diany, M.; Bouzid, A.H. An experimental-numerical procedure for stuffing box packing characterization and leak tests. J. Tribol. 2011, 133, 12201-1–12201-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuraev, A.S.; Turdiyev, S.A.; Jurayev, S.T.; Salimova, S.S.Q. Characteristics of packing gland seals in hydraulic systems of quarry excavators and results of comparative analysis of experimental tests. Vibroeng. Procedia 2024, 54, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, B.; Kirschmann, D.; Haas, W.; Bertsche, B. Accelerated testing of shaft seals as components with complex failure modes. In Proceedings of the Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium (RAMS), San Jose, CA, USA, 25–28 January 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, D.E. Design aspects of modern rotary shaft seals. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 1999, 213, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Kawakami, S. Effect of various fillers on the friction and wear of polytetrafluoroethylene-based composites. Wear 1982, 79, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedkar, J.; Negulescu, I.; Meletis, E.I. Sliding wear behavior of PTFE composites. Wear 2002, 252, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudresh, B.M.; Ravikumar, B.N. Investigation on Three body Abrasive Wear Behavior of Polyamide66/Polytetrafluroethylene(PA66/PTFE) Blends. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 2503–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, M. Perseverance Rover Corer Railizer Mechanism Development for Drill Feed and Stabilization. In Proceedings of the IEEE Aerospace Conference Proceedings 2022, Big Sky, MT, USA, 5–12 March 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker Hannifin Corp. PTFE Seal Design Guide. Available online: https://www.parker.com/literature/Packing/Packing%20-%20Literature/Catalog_PTFE-Seals_PDE3354-GB_1103.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Space Exploration|Bal Seal Engineering. Available online: https://www.balseal.com/space-exploration (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- McCook, N.L.; Burris, D.L.; Dickrell, P.L.; Sawyer, W.G. Cryogenic friction behavior of PTFE based solid lubricant composites. Tribol. Lett. 2005, 20, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 10088-1:2023; Stainless Steels—Part 1: List of Stainless Steels. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Yuan, X.D.; Yang, X.J. A study on friction and wear properties of PTFE coatings under vacuum conditions. Wear 2010, 269, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, I.R.; Handschuh, M.J. Preliminary Assessment of Seals for Dust Mitigation of Mechanical Components for Lunar Surface Systems. In Proceedings of the 40th Aerospace Mechanisms Symposium (2010), Cocoa Beach, FL, USA, 12–14 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, M.; Li, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Xiong, G. Abrasive wear behavior of PTFE for seal applications under abrasive-atmosphere sliding condition. Friction 2019, 8, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpagazehe, J.N.; Street, K.W.; Delgado, I.R.; Higgs, C.F. An experimental study of lunar dust erosive wear potential using the JSC-1AF lunar dust simulant. Wear 2014, 316, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalácska, G.; Barkó, G.; Shegawu, H.; Kalácska, Á.; Zsidai, L.; Keresztes, R.; Károly, Z. The Abrasive Effect of Moon and Mars Regolith Simulants on Stainless Steel Rotating Shaft and Polytetrafluoroethylene Sealing Material Pairs. Materials 2024, 17, 4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkó, G.; Kalácska, G.; Keresztes, R.; Zsidai, L.; Shegawu, H.; Kalácska, Á. Abrasion Evaluation of Moon and Mars Simulants on Rotating Shaft/Sealing Materials: Simulants and Structural Materials Review and Selection. Lubricants 2023, 11, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thermoplastics|SKF. Available online: https://www.skf.com/group/products/industrial-seals/materials/thermoplastics (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- CHETRA 1788|Chetra. Available online: https://chetra.hu/tomitozsinor-grafittomites-aramidtomites-x/chetra-1788/ (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- CHETRA 1777 MS|Chetra. Available online: https://chetra.hu/tomitozsinor-grafittomites-aramidtomites-x/chetra-1777-ms/ (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- ISO 148-1:2016; Metallic Materials—Charpy Pendulum Impact Test. ISO: Geneva, Switzerlan, 2016.

- 34CrNiMo6. Available online: https://steelnavigator.ovako.com/steel-grades/34crnimo6/ (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Lunar Highlands—(LHS-1) High-Fidelity Moon Dirt Simulant for Education and Research. Available online: https://spaceresourcetech.com/collections/lunar-simulants/products/lhs-1-lunar-highlands-simulant (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Mars Global(MGS-1) High-Fidelity Martian Dirt Simulant for Education and Research. Available online: https://spaceresourcetech.com/collections/martian-simulants/products/mgs-1-mars-global-simulant (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Dried Quartz Sand. Available online: https://www.euroquartz.be/producten/dried-quartz-sand/?lang=en (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Stakenborg, M.J.L. On the sealing mechanism of radial lip seals. Tribol. Int. 1988, 21, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Ma, S.; Zhang, M.; Yang, J.; Wang, D.; Zhang, L.; Xu, J. Wear Evolution of the Glass Fiber-Reinforced PTFE under Dry Sliding and Elevated Temperature. Materials 2019, 12, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenta, F.; Bolelli, G.; Pedrazzi, S.; Allesina, G.; Santeramo, F.; Bertarini, A.; Sassatelli, P.; Lusvarghi, L. Sliding wear behaviour of fibre-reinforced PTFE composites against coated and uncoated steel. Wear 2021, 486-487, 204097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briscoe, B. Wear of polymers: An essay on fundamental aspects. Wear 2021, 486–487, 204097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.T.; Top, M.; Pei, Y.T.; De Hosson, J.T.M. Wear and friction performance of PTFE filled epoxy composites with a high concentration of SiO2 particles. Wear 2015, 322–323, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, T.; Andersen, T.L.; Thorning, B.; Horsewell, A.; Vigild, M.E. Changes in the tribological behavior of an epoxy resin by incorporating CuO nanoparticles and PTFE microparticles. Wear 2008, 265, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descartes, S.; Berthier, Y. Rheology and flows of solid third bodies: Background and application to an MoS1.6 coating. Wear 2002, 252, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).