Abstract

This study investigates the influence of graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs) and the formation of nanosized Al4C3 on the tribological performance of hot extruded aluminum-based nanocomposites. Al/GNP nanocomposites with varying GNP contents (0, 0.1, 0.5, and 1.1 wt.%) were fabricated through powder metallurgy, including ball milling, compaction, and hot extrusion at 500 °C, which was designed to facilitate the formation of nanosized carbides during the extrusion process. The effect of GNPs and nanosized carbides on the tribological properties of the composites was evaluated using dry friction pin-on-disk tests to assess wear resistance and the coefficient of friction (COF). Microstructural analyses using scanning electron microscopy and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy confirmed the uniform distribution of GNPs and the formation of nanosized Al4C3 in the samples. Incorporating 0.1 wt.% GNPs resulted in the lowest wear mass loss (1.40 mg) while maintaining a stable COF (0.52), attributed to enhanced lubrication and load transfer. Although a higher GNP content (1.1 wt.%) resulted in increased wear due to agglomeration, the nanocomposite still demonstrated superior wear resistance compared to the unreinforced aluminum matrix. These findings underscore the potential of combining nanotechnology with precise processing techniques to enhance the wear and friction properties of aluminum-based composites.

1. Introduction

Aluminum Metal Matrix Composites (AMMCs) are integral to industries such as automotive, aerospace, and electronics, owing to their advantageous properties: high strength-to-weight ratio, low density, and outstanding thermal and electrical conductivity [1]. These characteristics make aluminum a preferred material for applications where weight reduction without compromising strength is crucial [2,3].

To further enhance aluminum’s mechanical and tribological properties, reinforcing it with various materials has emerged as a promising approach. Reinforcements such as Al2O3 [4], known for its hardness and wear resistance; SiC [5,6], which offers high thermal stability and strength; and B4C, recognized for its exceptional hardness and low density, are frequently employed in AMMCs. Additionally, composite coatings on aluminum and its alloys, such as nanocomposite coatings [7,8], ceramic coatings [9,10], and ceramic coatings [11], are widely used to enhance surface hardness and wear resistance. Graphite is another common reinforcement due to its self-lubricating properties and ability to reduce the COF effectively [12,13]. Graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs) are renowned for their exceptional mechanical strength, high surface area, and excellent lubricating properties [14,15]. These characteristics make GNPs an attractive reinforcement material in composite fabrication. Incorporating GNPs into aluminum matrices can significantly enhance load transfer capabilities, improve wear resistance, and reduce the COF [16]. Studies have shown that aluminum composites reinforced with GNPs exhibit superior mechanical and tribological behaviors, making them suitable for high-performance engineering applications.

Fathy et al. demonstrated the superior mechanical and tribological properties of hybrid Al-Al2O3/GNP nanocomposites synthesized using the electroless deposition of nickel-coated reinforcements [17]. Their work achieved remarkable improvements in compressive strength, hardness, and wear resistance, attributing these enhancements to the mechanical robustness and self-lubricating properties of GNPs, along with the prevention of detrimental Al3C4 phase formation. Similarly, Ghazaly et al. showed that AA2124-GNP composites, fabricated via powder metallurgy, exhibited an optimal tribological performance at 3 wt.% graphene reinforcement, transitioning from a severe to a mild wear regime compared to unreinforced aluminum [18]. Expanding on these findings, Mishra et al. analyzed the wear behavior of Al-GNP composites and reported that 1 wt.% GNPs maximized hardness and wear resistance, with homogeneous microstructures contributing to the composite’s stability [19]. Kumar and Xavior further explored the fatigue and wear properties of Al6061-GNP composites, revealing improved surface hardness and reduced mass loss under varying loads, owing to the dispersion of graphene flakes through ultrasonication and ball milling [20]. Innovative manufacturing methods also play a key role in enhancing AMMC properties. Bao et al. utilized ultrasonic-assisted casting followed by T6 heat treatment to fabricate ADC12-GNP composites, achieving a 63.3% reduction in wear rate and significant improvements in surface roughness and coefficient of friction due to self-lubrication and nanoscale precipitate interactions [21]. Similarly, Wu et al. utilized selective laser melting (SLM) to produce AlSi10Mg-GNP composites, reporting a 42.9% reduction in wear rate and substantial hardness improvements, demonstrating the versatility of GNP reinforcements in AMMCs [22]. Additionally, Cygan et al. incorporated multilayered graphene and graphene oxide into alumina matrix composites using spark plasma sintering (SPS). Their results highlighted a 53.3% reduction in wear rate for 1 wt.% GNP composites, emphasizing the synergy between alumina and graphene-family materials for tribological performance [23].

Despite these advancements, incorporating GNPs into aluminum matrices introduces challenges. One critical issue is the formation of Al4C3 carbides at the interface between GNPs and aluminum during composite production. Al4C3 is a brittle and thermodynamically unstable compound that weakens interfacial bonding and causes localized stress concentrations. Studies have confirmed interfacial reactions in C/Al composites, leading to Al4C3 phase formation [24,25]. This interfacial reaction has recently drawn significant attention as a key factor influencing both interfacial properties and mechanical performance [26,27]. Interestingly, Al4C3 has been shown to enhance load transfer efficiency due to its anchoring effect and the transformation of interfacial bonding from mechanical to strong chemical bonding [28,29,30]. Understanding the role of Al4C3 in shaping the tribological properties of aluminum–GNP composites is essential. Research demonstrates that adding 3 wt.% graphene to aluminum composites reduces the wear rate by 34% and lowers the COF by 25%. However, higher graphene content, such as 5 wt.%, can lead to agglomeration, resulting in increased wear rates [31].

A notable research gap is present in the investigation of AMMCs reinforced with GNPs. While existing studies primarily focus on broader tribological characteristics or utilize different fabrication techniques, the combined influence of controlled GNP content (0, 0.1, 0.5, and 1.1 wt.%) and nanosized Al4C3 formation, achieved through a specific powder metallurgy process involving ball milling, compaction, and hot extrusion at 500 °C, has not been investigated.

The originality of this study lies in its investigation of the combined effects of varying GNP content and the in situ formation of nanosized Al4C3 carbides on the tribological performance of aluminum-based nanocomposites. Previous research, including the works of Ghazaly et al. [18] and Mishra et al. [19], has predominantly focused on broader tribological properties or specific GNP concentrations without addressing the simultaneous effects of nanosized Al4C3 formation during processing. Unlike earlier studies that utilized alternative fabrication techniques such as selective laser melting (Wu et al. [22]) or ultrasonic-assisted casting (Bao et al. [21]), this research employs powder metallurgy coupled with hot extrusion at 500 °C to facilitate the controlled formation of nanosized Al4C3 carbides. This method allows for precise evaluation of the interplay between reinforcement distribution, carbide morphology, and tribological performance. This study investigates the influence of GNPs and the formation of nanosized Al4C3 on the tribological performance of hot-extruded Al-based nanocomposites. Al/GNP nanocomposites with varying GNP content (0, 0.1, 0.5, and 1.1 wt.%) were fabricated through powder metallurgy techniques, including ball milling, compaction, and hot extrusion at 500 °C, which facilitated the in situ formation of nanosized carbides during the extrusion process. Microstructural analyses conducted using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) confirmed the uniform distribution of GNPs within the Al matrix and the formation of nanosized Al4C3. The wear characteristics were compared to those of a prior study [32], which investigated the effects of GNPs and predominantly micron-sized Al4C3 on the tribological performance of aluminum-based nanocomposites. These composites were fabricated through extrusion at 400 °C, followed by annealing at 610 °C for 3 h to promote Al4C3 formation. This comparison highlights the impact of processing conditions and nanoscale carbide formation on the COF and wear rate of the composites, providing new insights into optimizing the tribological properties of Al/GNP nanocomposites.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Fabrication

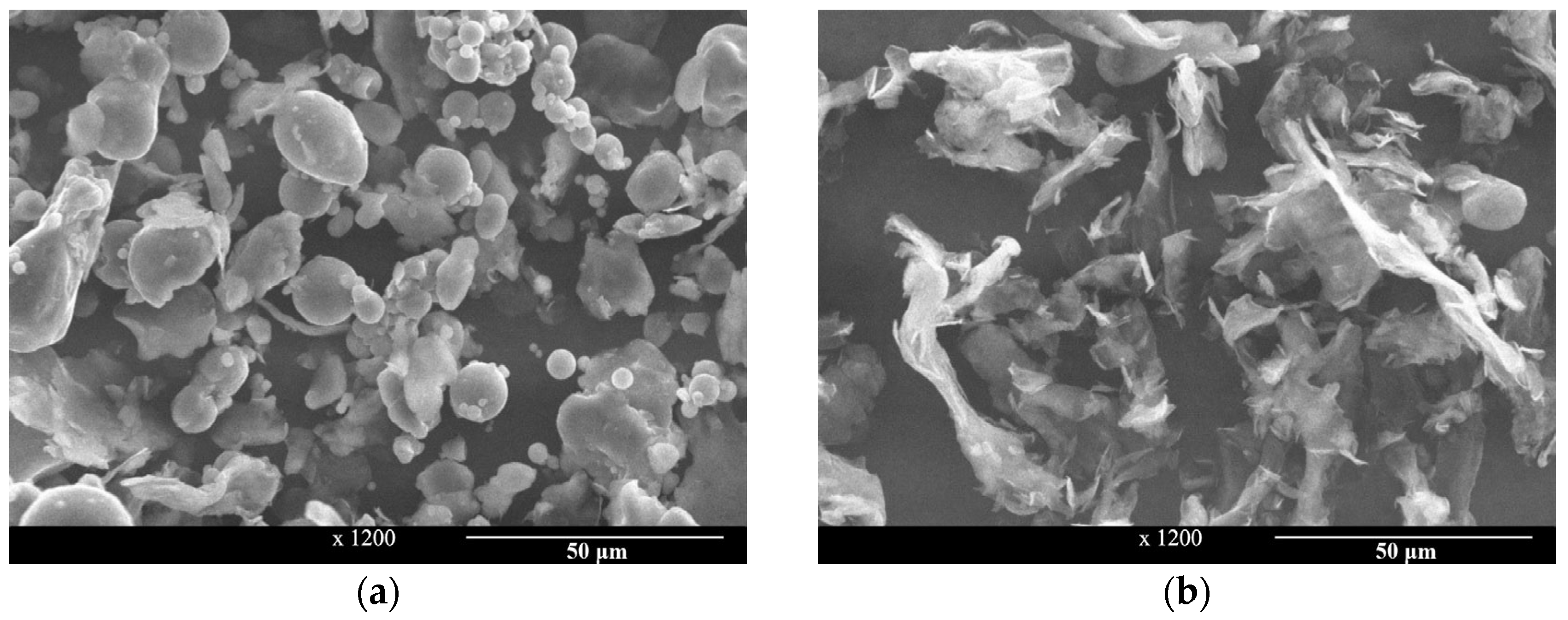

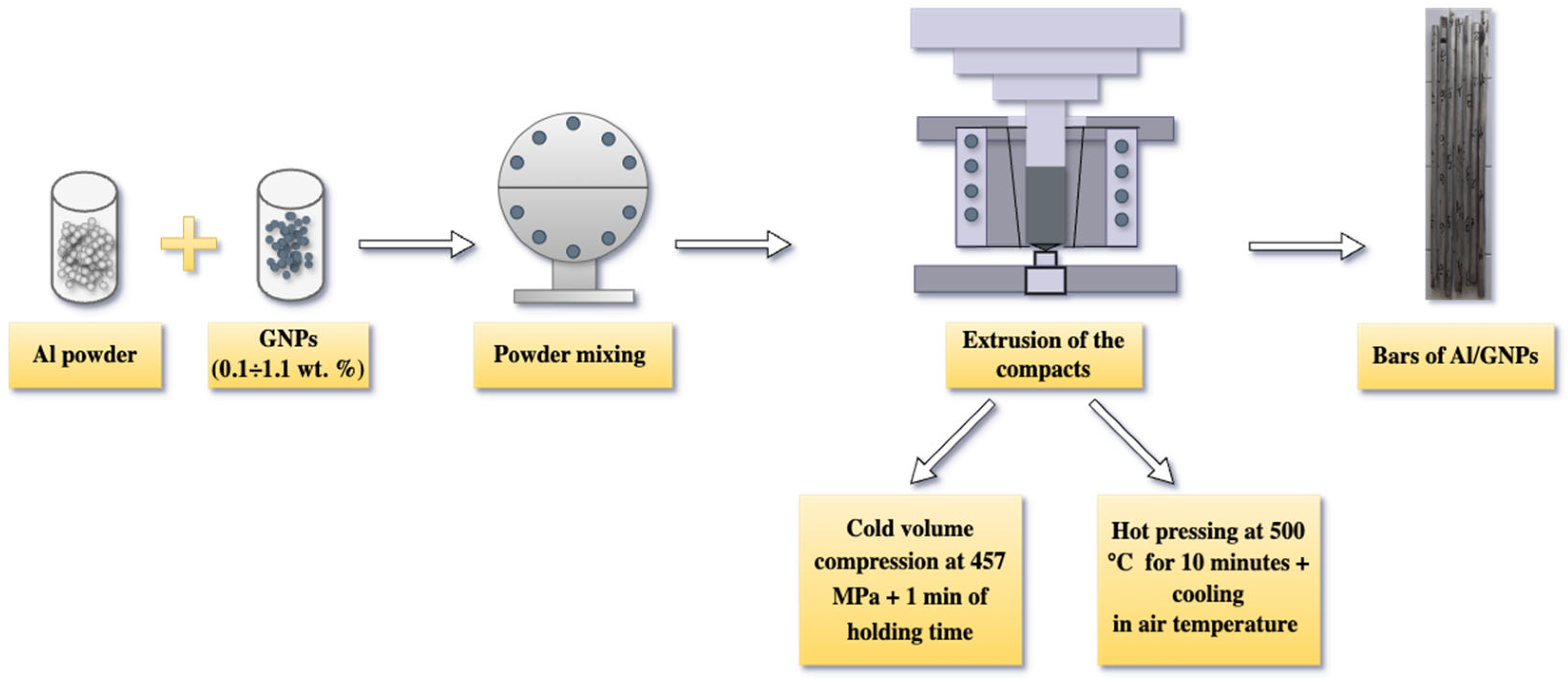

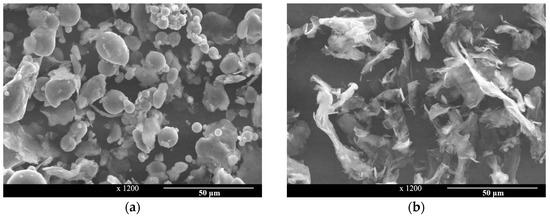

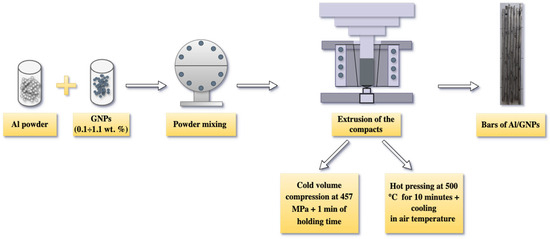

The nanocomposite materials consisted of Al powder with a purity of 99.5% and an average particle size of 37 µm (Figure 1a), and GNPs with a thickness of 6–8 nm and purity of 99.5% (Figure 1b). The Al powder and graphene nanoplatelets were mixed using a planetary agate ball mill equipped with 7 balls, each weighing 11.6 g. The milling parameters were as follows: speed of 700 revolutions per minute, milling time of 30 min, at room temperature, in an argon atmosphere. Four different compositions were prepared with GNP content at 0, 0.1, 0.5, and 1.1 wt.%, each mixture weighing 300 g. This study builds upon previous research [33,34] that investigated aluminum–graphene composites fabricated via powder metallurgy. Prior findings [34] demonstrated that Al4C3–graphene interfaces are coherent, providing a precondition for carbide nucleation on GNPs when the crystal orientation relationship between them is Al4C3(008)//C(002). The coherent boundary between the two phases also serves as a prerequisite for the strength of their connection. Li et al. [35] synthesized in situ nano-Al4C3 in CNT/Al composites, achieving high strength and exceptional ductility via friction stir processing. The improvement in ductility and strength is attributed to the strong Al4C3–Al interface and nanoscale size. However, the focus of this work was to develop nanocomposites featuring nanosized carbides as a result of the in situ reactions during the extrusion process. To achieve this, the compacts were heated to 370 °C for 20 min, followed by preheating the mold to 500 ± 10 °C, where the compacts remained for 4.5 min before being extruded under a pressure of 457 MPa for 60 s per piece. The final products were aluminum-based nanocomposite bars reinforced with GNPs, 12 mm in diameter, cooled in air. The formation of nanosized carbides during extrusion at 500 °C, resulting from the reaction between graphene and aluminum, was successfully achieved, eliminating the need for additional annealing of the extrudates at higher temperatures. Figure 2 illustrates the production process scheme for the Al/GNP nanocomposites.

Figure 1.

SEM images of the powders used for the fabrication of the nanocomposites: (a) Al powder with a purity of 99.5% and an average particle size of 37 µm; (b) GNPs with a thickness of 6–8 nm and a purity of 99.5%, adopted from [32].

Figure 2.

Fabrication process scheme of hot-extruded Al/GNP nanocomposites at 500 °C.

2.2. Characterization Methods

The extruded rods were characterized using SEM with EDS and subsequently subjected to dry sliding wear testing. The samples were wet ground in longitudinal sections on grinding paper with grit sizes ranging from 320 to 3000, followed by a two-step polishing process using an OPS suspension from Struers. The microstructure was examined by etching with a 0.5% HF water solution, and observations were made using scanning electron microscopy. SEM and EDS analyses were conducted using a HIROX SH-5500P SEM (Hirox Japan Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a ‘QUANTAX 100 Advanced’ EDS system (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). The operating conditions included an accelerating voltage of 20 kV, a working distance of 3–7 mm, and a secondary electron detector.

The Vickers microhardness of the composite cross-sections was quantified utilizing a Polyvar Met optical microscope (Reichert Jung, Vienna, Austria) integrated with a semi-automated micro-Vickers hardness measurement system (Micro-Duromat 5000, Reichert Jung, Vienna, Austria). Measurements were obtained using a calibrated Vickers indenter, characterized by a diamond pyramid with an apex angle of 136°. A standardized load of 0.05 kgf was applied for a dwell time of 10 s, followed by an additional 10 s of sustained pressure to ensure uniform indentation depth and minimize viscoelastic effects. Tribological properties were evaluated under dry sliding conditions using a Ducom TR-20 rotary (pin/ball-on-disk) tribometer (Ducom Instruments Pvt. Ltd., Bangalore, India). Test specimens were machined from the extruded rods on a lathe to achieve a height of 20 mm and a diameter of 12 mm, minimizing structural flaws that could affect wear behavior. The test parameters for the dry sliding wear tests were selected based on a prior study that evaluated annealed Al/GNP nanocomposites [32]. Specifically, a pin-on-disk system was utilized with a load of 30 N, a linear velocity of 0.9 m∙s⁻1, and a sliding distance of 540 m, and a counter disk made of EN-31 steel with a hardness of 62 HRC.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructural Characterization

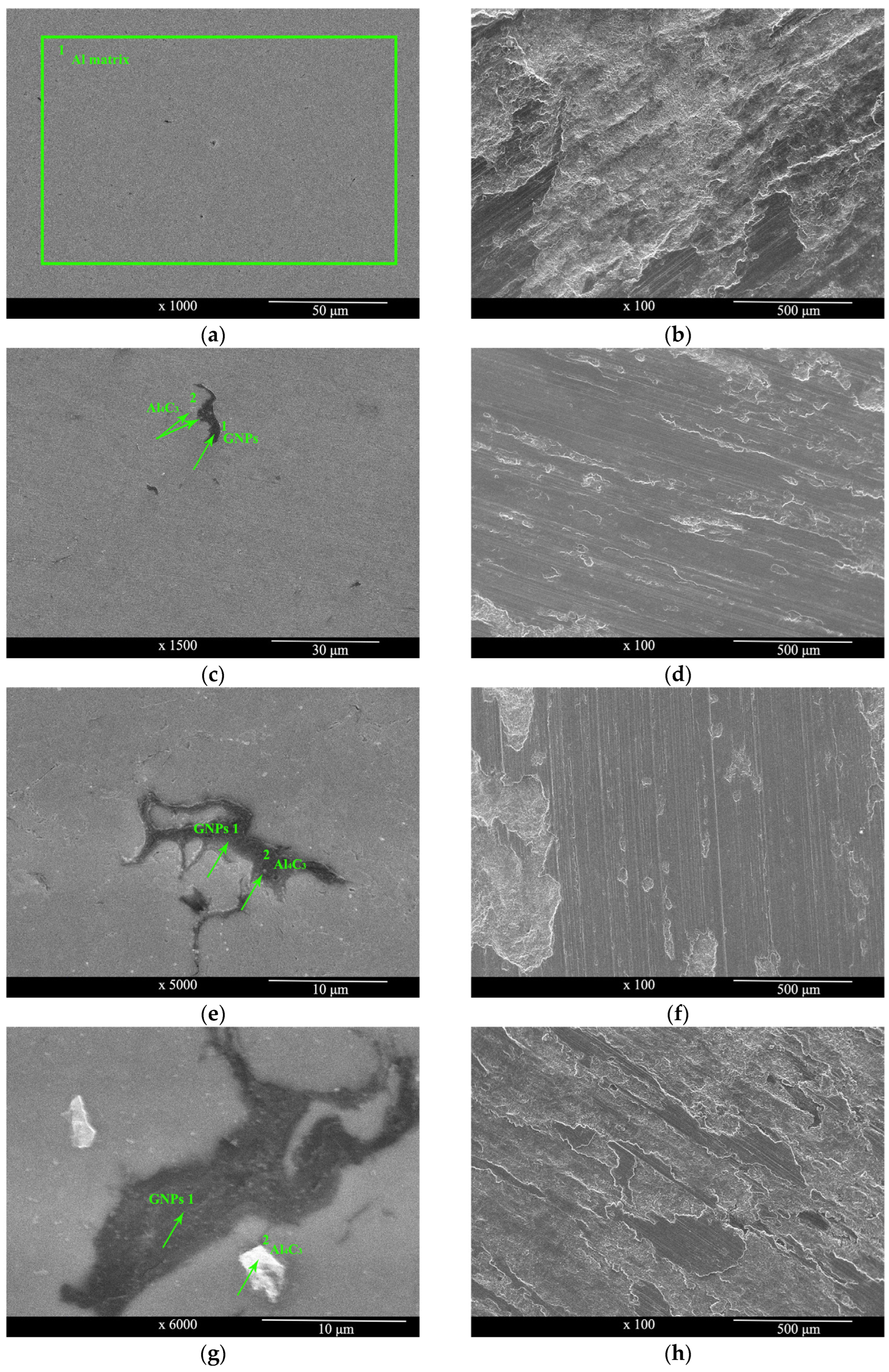

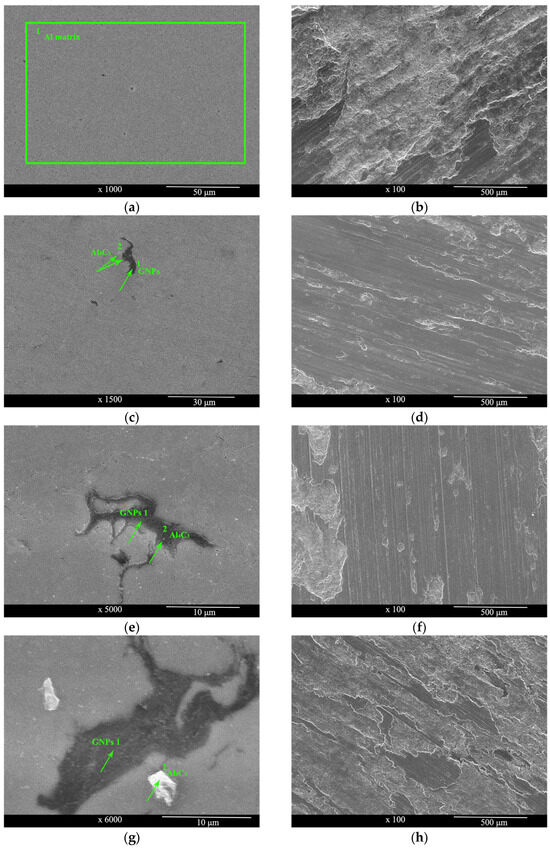

The microstructural characterization of non-annealed Al/GNP nanocomposites, as illustrated in Figure 3 and analyzed using EDS data from Table 1, provides valuable insights into the influence of GNP content on wear performance and material properties. Each SEM image highlights specific regions of interest, particularly the distribution of GNPs, the formation of Al4C3 carbides, and the changes in surface morphology before and after wear tests. The corresponding EDS results further elucidate the elemental composition within these zones, revealing the complex interplay between the aluminum matrix and the reinforcing GNPs.

Figure 3.

SEM images of surfaces with numbered zones corresponding to EDS analysis for the following materials: (a) Al, before wear test; (b) Al, after wear test; (c) Al with 0.1 wt.% GNPs, before wear test; (d) Al with 0.1 wt.% GNPs, after wear test; (e) Al with 0.5 wt.% GNPs, before wear test; (f) Al with 0.5 wt.% GNPs, after wear test; (g) Al with 1.1 wt.% GNPs, before wear test; (h) Al with 1.1 wt.% GNPs, after wear test.

Table 1.

EDS analysis results (in mass norm. %) of Al/GNPs (0–1.1 wt.%) prior to wear testing, focusing on regions 1–2 as highlighted in Figure 3.

For pure Al (Figure 3a,b), the SEM image before the wear test (Figure 3a) shows a smooth and homogeneous surface typical of unreinforced Al, with no visible secondary phases or particles. The EDS analysis confirms the composition is 100% aluminum, as expected. However, after the wear test (Figure 3b), the surface exhibits severe plastic deformation with pronounced grooves and roughness, indicating substantial material loss. This behavior aligns with the wear test results, where pure Al showed the highest mass wear (3.95 mg) and a relatively high COF of 0.58.

With the addition of 0.1 wt.% GNPs (Figure 3c,d), the microstructure undergoes noticeable changes. Before the wear test (Figure 3c), the SEM image reveals the presence of Al4C3 carbides and dispersed GNPs. EDS analysis for this region shows two distinct zones: Zone 1 contains 86.45% carbon and 13.55% Al, indicating a GNP-rich area, while Zone 2 shows a more balanced composition of 50.86% carbon and 49.14% Al, indicative of Al4C3 carbide formation due to aluminum–carbon interactions. After the wear test (Figure 3d), the surface displays finer grooves compared to pure aluminum, indicating improved wear resistance. However, the COF increased to 0.62 compared to 0.58 for pure Al. This increase can be attributed primarily to the agglomeration of Al4C3 carbides, which likely altered the surface characteristics and influenced the wear behavior. These carbide clusters would have increased interfacial shearing during sliding, contributing to a higher COF. Despite this, the addition of 0.1 wt.% GNPs significantly reduced mass wear to 1.40 mg—a 64.6% reduction compared to pure aluminum. The relatively fine dispersion of GNPs and the formation of a lubricating tribolayer during wear mitigated wear damage but could not fully offset the friction-increasing effect of the carbide.

At 0.5 wt.% GNPs (Figure 3e,f), the microstructure before the wear test (Figure 3e) shows better GNP dispersion but still features some agglomeration and Al4C3 carbides. The EDS analysis highlights Zone 1 with 68.41% carbon and 31.59% aluminum, indicating the presence of GNP-rich areas, while Zone 2 is predominantly aluminum (90.44%) with minimal carbon (9.56%), revealing the presence of Al4C3 carbides and dispersed GNPs. Notably, the carbides appear visibly larger in the SEM image compared to the 0.1 wt.% GNP sample, suggesting more significant clustering of Al4C3 particles. After the wear test (Figure 3f), the wear surface displays more defined grooves than the 0.1 wt.% GNP sample, but the wear resistance remains superior to pure Al. The wear results show a mass wear of 1.85 mg, which is significantly higher than the 1.40 mg observed for the 0.1 wt.% sample. This increase can be attributed to the larger Al4C3 carbides, which may contribute to higher wear rates under dry sliding wear conditions. The diminishing returns with increased GNP content highlight the adverse effects of carbide agglomeration on the material’s wear resistance. Nevertheless, the COF remains relatively low at 0.61, demonstrating that the reinforcing effects of GNPs are still beneficial, albeit less pronounced than at lower GNP concentrations. While the GNPs contribute to reducing friction, the larger carbides overshadow these effects, resulting in the higher wear observed at 0.5 wt.% GNPs.

At the highest GNP concentration (1.1 wt.%, Figure 3g,h), the microstructure reveals the significant agglomeration of GNPs and Al4C3 carbides before the wear test (Figure 3g). EDS analysis confirms the presence of highly carbon-rich regions (Zone 1: 81.80% carbon, 18.20% aluminum) alongside Al4C3-dominant zones (Zone 2: 67.06% aluminum, 32.94% carbon). The Al4C3 particles are visibly larger compared to those in the 0.1 and 0.5 wt.% nanocomposites and appear to form distinct agglomerates. These Al4C3 agglomerates act as stress concentrators, significantly reducing the effectiveness of the reinforcement. After the wear test (Figure 3h), the surface shows increased roughness with clear evidence of particle pull-out, leading to slightly higher mass wear (2.70 mg) and a COF of 0.56. Despite the slightly lower COF compared to the 0.1 wt.% and 0.5 wt.% composites, the COF value remains within the deviation range observed for the other nanocomposites, indicating no significant improvement in friction behavior at this GNP concentration. The contact surface is visibly the worst among the nanocomposites but still better than that of the unreinforced aluminum material. This performance indicates that excessive GNP content promotes the formation of larger Al4C3 carbides and their agglomeration, which compromises both wear resistance and overall mechanical properties.

The microstructural characterization of non-annealed Al/GNP nanocomposites highlights the influence of GNP content on wear performance and material properties. Pure Al shows a smooth surface before wear, with significant plastic deformation and roughness after wear, resulting in the highest mass wear (3.95 mg) and a COF of 0.58. The addition of 0.1 wt.% GNPs introduces Al4C3 carbides and GNP dispersions, reducing the mass wear to 1.40 mg—a 64.6% reduction—despite a slight COF increase to 0.62 due to carbide agglomeration. At 0.5 wt.% GNPs, better GNP dispersion is observed, but larger Al4C3 carbides lead to increased mass wear (1.85 mg). At 1.1 wt.% GNPs, excessive GNP content results in significant Al4C3 agglomeration, acting as stress concentrators, leading to the highest roughness and mass wear among the nanocomposites (2.70 mg) and no significant improvement in COF (0.56). While GNP addition improves wear resistance compared to pure Al, excessive concentrations compromise mechanical properties due to larger carbide formations and their agglomeration. These findings align with studies such as that conducted by Wu et al. [22], who identified an optimal GNP content of around 0.3 wt.% for Al–GNP composites, beyond which agglomeration and reduced performance were observed. Similarly, Ghazaly et al. [31] reported that incorporating a high fraction (5 wt.%) of graphene caused significant agglomeration and higher wear rates. Zhang et al. [36] further demonstrated that 1 vol.% GNSs reinforcement significantly refined Al grains and improved the reinforcement distribution in the matrix, highlighting the importance of balancing reinforcement content to optimize mechanical and tribological properties. While GNP addition improves wear resistance compared to pure Al, excessive concentrations compromise mechanical properties due to larger carbide formations and their agglomeration.

3.2. Wear Behavior and Microhardness

The tribological performance of the non-annealed Al–GNP nanocomposites was evaluated under dry sliding wear conditions using a pin-on-disk tribometer. The test specimens were machined with a height of 20 mm and a diameter of 12 mm to minimize structural flaws. Testing was conducted at room temperature with a normal load of 30 N, a sliding speed of 0.9 m∙s⁻1, and a total sliding distance of 540 m. An EN-31 steel disk with a hardness of 62 HRC served as the counter surface. The wear performance was assessed by measuring mass loss using a high-precision analytical balance, and the COF was recorded during testing. The results were compared to previously reported annealed Al/GNP samples [32], comparing the effects of annealing on the COF and mass wear across varying GNP concentrations.

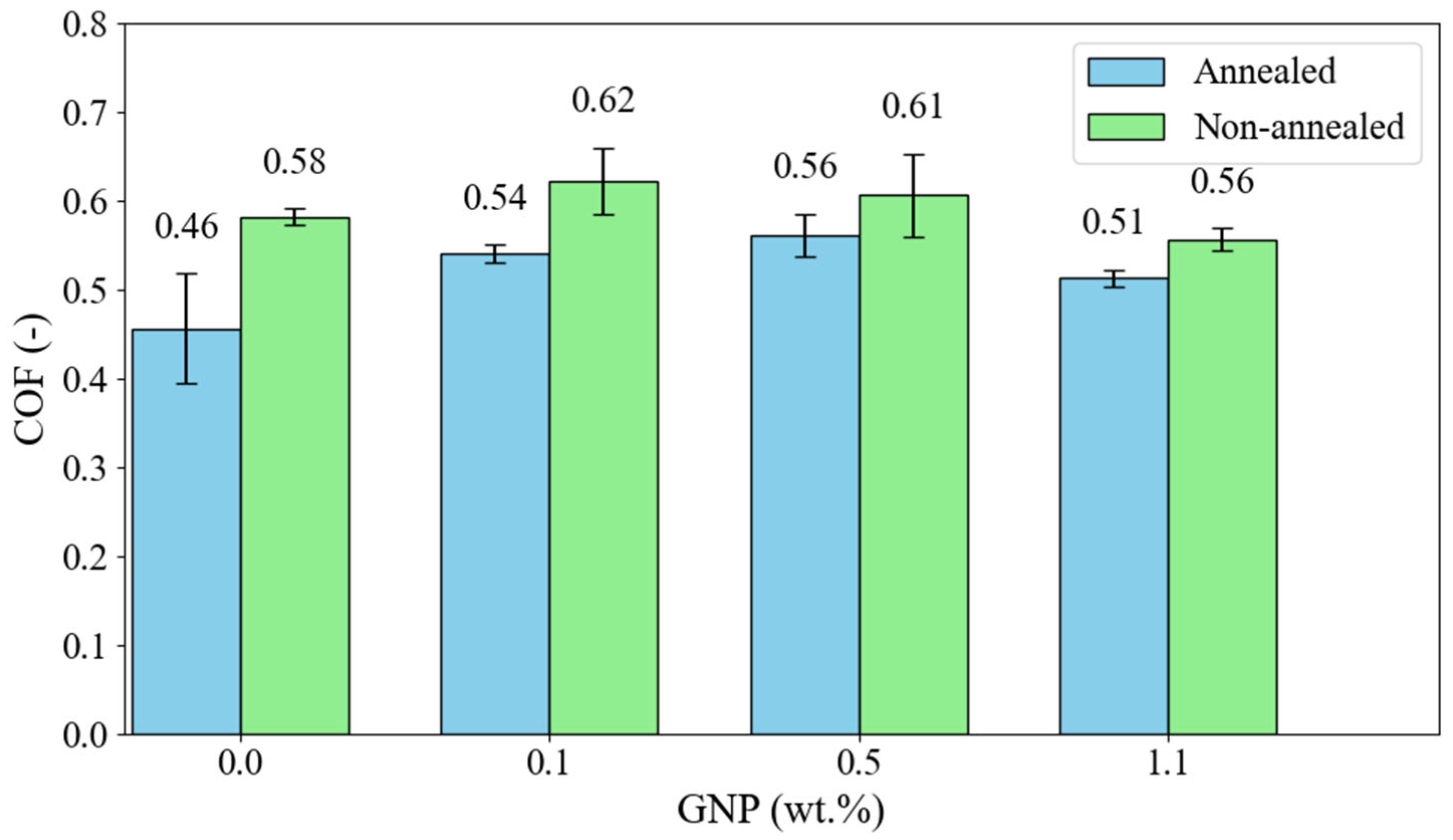

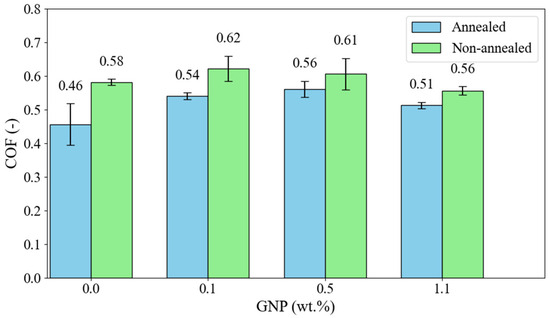

Figure 4 presents the COF vs. sliding distance test results for Al with GNPs (0–1.1 wt.%) under dry sliding friction conditions at room temperature, conducted at a 30 N load, 0.9 m∙s⁻1 sliding speed, and a 540 m sliding distance, including both annealed and non-annealed materials. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the COF values for annealed and non-annealed Al–GNP nanocomposites. The annealing process consistently reduced the COF across all GNP concentrations, with the most pronounced effect observed in pure aluminum (0 wt.% GNPs). Non-annealed samples exhibited a COF of 0.58, which was 26.1% higher than the annealed samples (0.46). This indicates that annealing enhances the surface interaction by refining the matrix structure, potentially leading to improved load distribution during dry sliding wear tests. At 0.1 wt.% GNP, the COF for non-annealed samples was 0.62, 14.8% higher than the annealed samples (0.54). This difference diminished further with increasing GNP content; at 0.5 wt.% GNPs, the non-annealed samples showed a COF of 0.61, only 8.9% higher than annealed samples (0.56). At the highest GNP concentration (1.1 wt.%), the COF difference narrowed further to 9.8% (0.56 for non-annealed vs. 0.51 for annealed samples). These results suggest that annealing enhances frictional performance, particularly in pure aluminum and composites with low GNP content, possibly by promoting better GNP–matrix bonding and a more uniform microstructure.

Figure 4.

COF vs. sliding distance test results for Al with GNPs (0–1.1 wt.%) under dry sliding friction conditions at room temperature. The wear tests were conducted at a 30 N load, 0.9 m∙s−1 sliding speed, and a 540 m sliding distance. Results include both annealed and non-annealed materials.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the COF for annealed and non-annealed Al–GNP nanocomposites at varying GNP contents (0–1.1 wt.%).

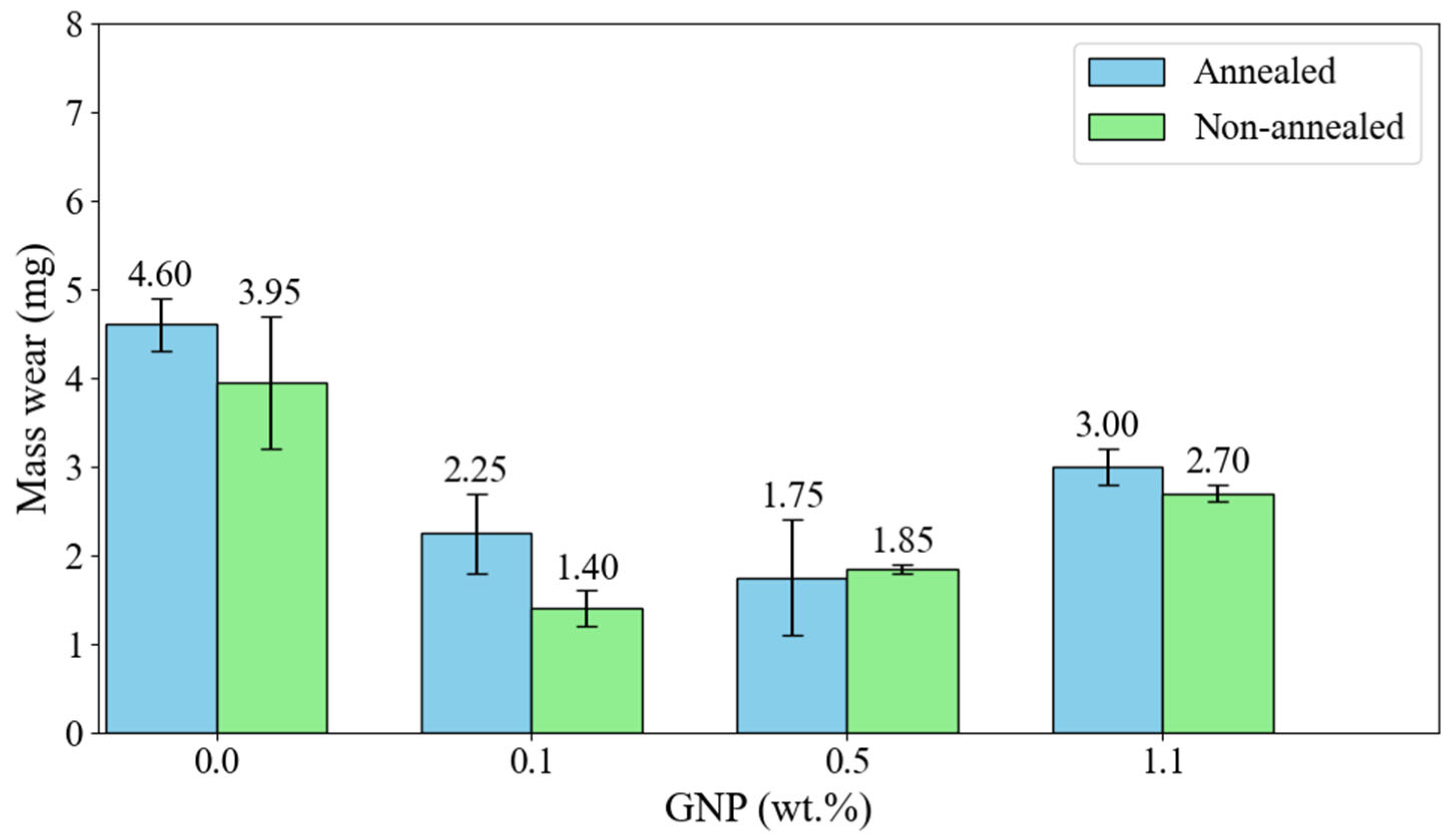

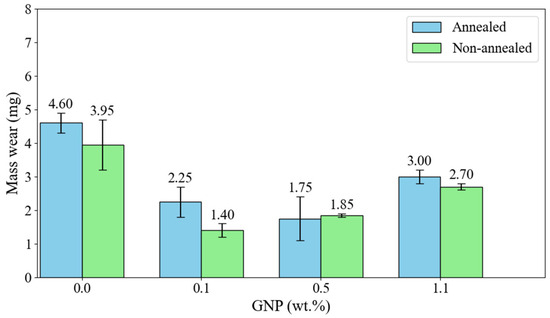

Figure 5 shows the mass wear results for Al with GNPs (0–1.1 wt.%) under dry sliding friction conditions at room temperature, conducted at a 30 N load, 0.9 m∙s⁻1 sliding speed, and a 540 m sliding distance, including both annealed and non-annealed materials. Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for the mass wear (mg) of annealed and non-annealed Al–GNP nanocomposites. Mass wear trends revealed a more complex relationship between annealing, GNP content, and tribological performance. For pure aluminum (0 wt.% GNPs), annealed samples exhibited 16.5% higher mass wear than non-annealed samples (4.60 mg vs. 3.95 mg), likely due to microstructural changes such as grain refinement induced by annealing, which may reduce hardness in the absence of reinforcements. At 0.1 wt.% GNPs, this trend became even more pronounced, with annealed samples showing 60.7% higher mass wear (2.25 mg vs. 1.40 mg). The higher wear in annealed samples could be attributed to the thermal treatment altering the matrix-reinforcement interaction, reducing the effectiveness of GNPs in mitigating wear. Interestingly, the trend reversed at 0.5 wt.% GNPs, where annealed samples exhibited 5.7% lower mass wear compared to non-annealed samples (1.75 mg vs. 1.85 mg). This reversal suggests that at intermediate GNP concentrations, annealing enhances the stress transfer capabilities of the GNPs and improves their dispersion within the matrix, resulting in better wear resistance. At 1.1 wt.% GNP, the trend shifted again, with annealed samples showing 11.1% higher mass wear than non-annealed samples (3.00 mg vs. 2.70 mg). The excessive GNP content likely led to agglomeration and the formation of larger Al4C3 particles in both cases, but the annealing process may have exacerbated this effect. These results are consistent with prior research [32] on the tribological performance of GNP-reinforced composites.

Figure 5.

Mass wear results for Al with GNPs (0–1.1 wt.%) under dry sliding friction conditions at room temperature. The wear tests were conducted at a 30 N load, 0.9 m∙s⁻1 sliding speed, and a 540 m sliding distance. Results include both annealed and non-annealed materials.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of the mass wear (mg) for annealed and non-annealed Al–GNP nanocomposites at varying GNP contents (0–1.1 wt.%).

The considerations of the results highlight the critical role of GNP content in influencing the wear resistance and COF of Al–GNP nanocomposites. Optimal performance is achieved through a balance between adequate GNP dispersion and the minimization of agglomeration and Al4C3 carbide clustering, which can act as stress concentrators and reduce reinforcement efficiency. The interplay between microstructural features and experimental conditions underscores the importance of precise control over GNP content and processing techniques to optimize tribological properties. These findings emphasize the need to tailor reinforcement levels to avoid diminishing returns at higher concentrations, ensuring practical applicability in engineering contexts.

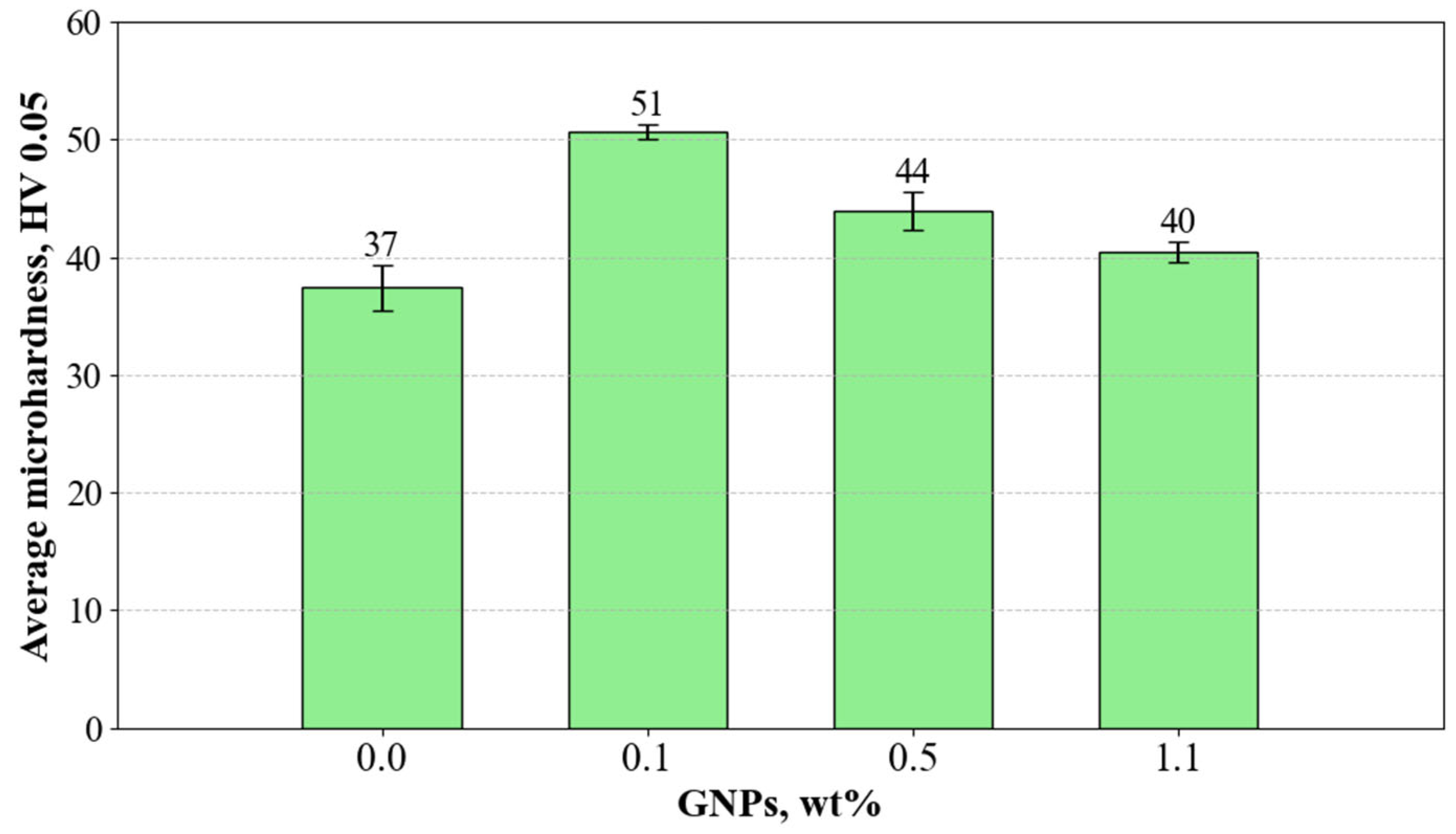

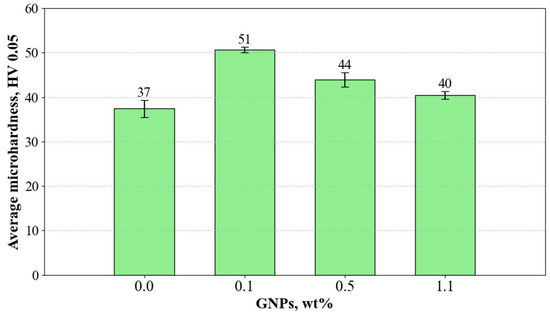

The microhardness of the Al–GNP nanocomposites obtained through hot extrusion, as shown in Figure 6, reveals significant variations with changing GNP content. The pure aluminum sample exhibits the lowest average microhardness (37 HV), indicative of its unreinforced structure. The addition of 0.1 wt.% GNP results in the highest microhardness (51 HV), which can be attributed to the uniform dispersion of GNPs and the formation of nanosized Al4C3 carbides. At 0.5 wt.% GNPs, the microhardness decreases slightly to 44 HV, likely due to the partial agglomeration of GNPs. This trend continues at 1.1 wt.% GNPs, where excessive GNP content further increases agglomeration and clustering, resulting in a microhardness of 40 HV. These findings suggest that while the addition of GNPs improves the hardness of the composite, maintaining an optimal GNP content is crucial to avoid diminishing returns caused by agglomeration and clustering.

Figure 6.

Average microhardness (HV 0.05) of Al-GNP nanocomposites with varying GNP contents (0.0, 0.1, 0.5, and 1.1 wt.%) obtained through hot extrusion.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the tribological properties under dry sliding wear conditions of hot-extruded Al/GNP nanocomposites fabricated at 500 °C using powder metallurgy techniques and evaluated the effects of GNP content and in situ nanosized Al4C3 formation during extrusion. The non-annealed composites’ wear results were compared with those obtained under the same testing conditions for annealed Al/GNP nanocomposites. The results reveal several key findings:

Microstructural Insights:

- The incorporation of GNPs into the aluminum matrix and the in situ formation of nanosized Al4C3 carbides were successfully achieved through extrusion at 500 °C.

- SEM and EDS analyses confirmed the uniform distribution of GNPs and the formation of the Al4C3 particles. However, with increasing GNP concentrations, the Al4C3 particles became visibly larger, and at higher concentrations (1.1 wt.%), agglomeration and the formation of larger Al4C3 clusters were observed, which acted as stress concentrators.

- Microhardness measurements showed that 0.1 wt.% GNPs led to the highest hardness (51 HV) due to uniform dispersion and nanosized Al4C3 formation, while higher GNP contents (0.5 and 1.1 wt.%) resulted in decreased hardness due to agglomeration and clustering effects.

Tribological Performance:

- Non-annealed nanocomposites exhibited improved wear resistance compared to pure aluminum. The addition of 0.1 wt.% GNPs resulted in a significant reduction in mass wear (64.6%) compared to pure Al, demonstrating the reinforcing effects of GNPs and the formation of a lubricating tribolayer.

- However, excessive GNP content (1.1 wt.%) resulted in increased wear and compromised performance due to agglomeration and carbide clustering.

- Annealing consistently reduced the COF across all GNP concentrations, with the most pronounced effect observed in pure aluminum. For instance, the COF of annealed pure aluminum (0.46) was 26.1% lower than that of non-annealed pure aluminum (0.58). Among the nanocomposites, the best COF results were observed at 1.1 wt.% GNPs for both annealed (0.51) and non-annealed (0.56) samples.

- Mass wear trends were more complex. Non-annealed composites outperformed annealed counterparts at lower GNP contents, particularly at 0.1 wt.% GNPs, where the non-annealed sample exhibited significantly lower mass wear of 1.40 mg compared to 2.25 mg for the annealed sample. This highlights the superior wear resistance of the non-annealed composite at this concentration. At 0.5 wt.% GNPs, the trend reversed slightly, with the annealed sample showing marginally better wear resistance (1.75 mg) compared to the non-annealed sample (1.85 mg).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K. and R.L.; methodology, M.K, R.L, V.P. and R.D.; software, M.K, R.L, V.P. and R.D.; validation, M.K, R.L, V.P. and R.D.; formal analysis, M.K. and R.L.; investigation, M.K. and R.L.; resources, M.K. and R.L.; data curation, M.K. and R.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K. and R.L.; writing—review and editing, M.K. and R.L.; visualization, M.K, R.L, V.P. and R.D.; supervision, R.L.; project administration, R.L.; funding acquisition, R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the BULGARIAN NATIONAL SCIENCE FUND, Project KΠ–06–H57/17 “Fabrication of aluminum–graphene nanocomposites by powder metallurgical method and investigation of their nano-, microstructure, mechanical and tribological properties”.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the European Regional Development Fund within the OP Science and Education for Smart Growth 2014–2020, Project CoE “National Center of Mechatronics and Clean Technologies” (BG05M2OP001-1.001-0008), for providing the SEM equipment. Special appreciation is also extended to Daniela Shouleva, from the Space Research and Technology Institute at Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, for her assistance in mixing the powders in a planetary mill.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sambathkumar, M.; Gukendran, R.; Mohanraj, T.; Karupannasamy, D.K.; Natarajan, N.; Christopher, D.S. A Systematic Review on the Mechanical, Tribological, and Corrosion Properties of Al 7075 Metal Matrix Composites Fabricated through Stir Casting Process. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Chen, X.; Li, Y. Fabrication, Properties, and Applications of Open-Cell Aluminum Foams: A Review. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 62, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chak, V.; Chattopadhyay, H.; Dora, T.L. A Review on Fabrication Methods, Reinforcements and Mechanical Properties of Aluminum Matrix Composites. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 56, 1059–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beder, M.; Varol, T.; Akçay, S.B. Impact of High Al2O3 Content on the Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Wear Behavior Al–Cu–Mg/Al2O3 Composites Prepared by Mechanical Milling. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 38610–38631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadhu, K.K.; Prajapati, P.K.; Mandal, N.; Sahoo, R.R. Tribo-Mechanical Evaluation of SiC-Reinforced Wear-Resistant Aluminium Composite Fabricated through Powder Metallurgy. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 42, 111184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhu, J.; Li, G.; Guan, F.; Yu, Y.; Fan, Z. Enhanced Mechanical Properties of 6082 Aluminum Alloy via SiC Addition Combined with Squeeze Casting. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 88, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkov, V.; Valov, R.; Simeonova, S.; Kandeva, M. Characteristics and properties of chromium coatings with Diamond nanoparticles deposited directly on aluminum alloys. Arch. Foundry Eng. 2020, 20, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidikova, N.; Sulowski, M.; Madej, M.; Valov, R.; Petkov, V. Mechanical Properties of Composite Coatings of Chromium and Nanodiamonds on Aluminum. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 145, 05012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K.; Motallebzadeh, A.; Kakooei, S.; Nguyen, T.A.; Behera, A. (Eds.) Advanced Ceramic Coatings; Elsevier Series on Advanced Ceramic Materials; Elsevier—Health Sciences Division: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2023; ISBN 9780323996594. [Google Scholar]

- Pancrecious, J.K.; Deepa, J.P.; Jayan, V.; Bill, U.S.; Rajan, T.P.D.; Pai, B.C. Nanoceria Induced Grain Refinement in Electroless Ni-B-CeO2 Composite Coating for Enhanced Wear and Corrosion Resistance of Aluminium Alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 356, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.G.; Wang, C.; Jiang, Y.; Li, H.; Lu, G.; Wang, Z.X. Microstructure and Properties of Al2O3/TiO2 Nanostructured Ceramic Composite Coatings Prepared by Plasma Spraying. J. Alloys Compd. 2012, 544, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, K.; Vasanthakumar, P. Mechanical Properties of Al-Cu Alloy Metal Matrix Composite Reinforced with B4C, Graphite and Wear Rate Modeling by Taguchi Method. Mater. Today 2019, 18, 3150–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.S.; Kordijazi, A.; Rohatgi, P.K.; Nosonovsky, M. Application of Triboinformatics Approach in Tribological Studies of Aluminum Alloys and Aluminum-Graphite Metal Matrix Composites. In The Minerals, Metals & Materials Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 41–51. ISBN 9783030925666. [Google Scholar]

- Rashad, M.; Pan, F.; Yu, Z.; Asif, M.; Lin, H.; Pan, R. Investigation on Microstructural, Mechanical and Electrochemical Properties of Aluminum Composites Reinforced with Graphene Nanoplatelets. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2015, 25, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabandeh-Khorshid, M.; Omrani, E.; Menezes, P.L.; Rohatgi, P.K. Tribological Performance of Self-Lubricating Aluminum Matrix Nanocomposites: Role of Graphene Nanoplatelets. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2016, 19, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Singh, S.; Angra, S. Dry Sliding Wear and Microstructural Behavior of Stir-Cast Al6061-Based Composite Reinforced with Cerium Oxide and Graphene Nanoplatelets. Wear 2023, 516–517, 204615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy, A.; Abu-Oqail, A.; Wagih, A. Improved Mechanical and Wear Properties of Hybrid Al-Al2O3/GNPs Electro-Less Coated Ni Nanocomposite. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 22135–22145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazaly, A.; Seif, B.; Salem, H.G. Mechanical and Tribological Properties of AA2124-graphene Self Lubricating Nanocomposite. In Light Metals 2013; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 411–415. [Google Scholar]

- Kishore Mishra, T.; Kumar, P.; Jain, P. Effects of Graphene Content on the Wear Properties of Aluminum Matrix Composites Prepared by Powder Metallurgy Route. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, in press. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.G.P.; Xavior, M.A. Fatigue and Wear Behavior of Al6061–Graphene Composites Synthesized by Powder Metallurgy. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2016, 69, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Yan, H. Influence of T6 Heat Treatment on the Microstructure and Tribological Properties of ADC12-GNPs Composites. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2023, 140, 110497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhao, Z.; Bai, P.; Zhao, W.; Li, Y.; Liang, M.; Liao, H.; Huo, P.; Li, J. Wear Resistance of Graphene Nano-Platelets (GNPs) Reinforced AlSi10Mg Matrix Composite Prepared by SLM. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 503, 144156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cygan, T.; Petrus, M.; Wozniak, J.; Cygan, S.; Teklińska, D.; Kostecki, M.; Jaworska, L.; Olszyna, A. Mechanical Properties and Tribological Performance of Alumina Matrix Composites Reinforced with Graphene-Family Materials. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 7170–7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, P.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Meng, Q.; Tan, X.; Xiu, Z.; Qiao, J.; Yu, Z.; Wu, G. Microstructure and Tensile Properties of 5083 Al Matrix Composites Reinforced with Graphene Oxide and Graphene Nanoplates Prepared by Pressure Infiltration Method. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2018, 109, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, E.; Li, J.; He, C.; Zhao, N. Investigation of the Evolution and Strengthening Effect of Aluminum Carbide for In-Situ Preparation of Carbon Nanosheets/Aluminum Composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 764, 138139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Yamaguchi, T.; Kikuchi, K.; Nomura, N.; Kawasaki, A. Effectively Enhanced Load Transfer by Interfacial Reactions in Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube Reinforced Al Matrix Composites. Acta Mater. 2017, 125, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Shen, J.; Ye, X.; Imai, H.; Umeda, J.; Takahashi, M.; Kondoh, K. Solid-State Interfacial Reaction and Load Transfer Efficiency in Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs)-Reinforced Aluminum Matrix Composites. Carbon N. Y. 2017, 114, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, B.; Liu, K.; Xiong, W.; Wu, X.; Sun, J. Strengthening Effect Induced by Interfacial Reaction in Graphene Nanoplatelets Reinforced Aluminum Matrix Composites. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 845, 156282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Mikulova, P.; Fan, Y.; Kikuchi, K.; Nomura, N.; Kawasaki, A. Interfacial Reaction Induced Efficient Load Transfer in Few-Layer Graphene Reinforced Al Matrix Composites for High-Performance Conductor. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 167, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Tan, Z.; Fan, G.; Zhang, Z.; Xiong, D.-B.; Guo, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D. Nucleation and Growth Mechanisms of Interfacial Carbide in Graphene Nanosheet/Al Composites. Carbon N. Y. 2020, 161, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ghazaly, A.; Anis, G.; Salem, H.G. Effect of Graphene Addition on the Mechanical and Tribological Behavior of Nanostructured AA2124 Self-Lubricating Metal Matrix Composite. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2017, 95, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolev, M.; Lazarova, R.; Petkov, V.; Mourdjeva, Y.; Nihtianova, D. Investigating the Effects of Graphene Nanoplatelets and Al4C3 on the Tribological Performance of Aluminum-Based Nanocomposites. Metals 2023, 13, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarova, R.; Mourdjeva, Y.; Nihtianova, D.; Stefanov, G.; Petkov, V. Fabrication and Characterization of Aluminum-Graphene Nano-Platelets—Nano-Sized Al4C3 Composite. Metals 2022, 12, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourdjeva, Y.; Karashanova, D.; Nihtianova, D.; Lazarova, R. Microstructural Characteristics of Al4C3 Phase and the Interfaces in Al/Graphene Nanoplatelet Composites and Their Effect on the Mechanical Properties. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2024, 33, 11607–11616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, Y.; Yan, D.; Tan, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, K. In Situ Synthesized Nano-Al4C3 Reinforced Aluminum Matrix Composites via Friction Stir Processing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 2658–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Wu, H.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, Z. Effect of Graphene on the Tribolayer of Aluminum Matrix Composite during Dry Sliding Wear. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 358, 907–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).