Abstract

Although a fair amount of research around older adults’ perception of digital technology exists, there is only a moderate amount of research investigating older people’s reactions and sense-making in real-world contexts with emerging digital tools. This paper reports on the constructivist research approach used by the author, which initiated co-production with participants to gather older and younger adults’ reactions towards digital video connectivity during a series of design research interventions. For this, the author had built a research tool, the Teletalker kiosks (TT), which connected two locations using digital live video to provide a ‘window into the other space’. Participants, if they wished, could activate the volume with a designed mechanism aimed at non-computer literate people, which was used in order to speak to each other. The three connections were between an older people’s charity day centre and the university, between two locations at the university, and between two-day centres in the U.K. The returns collected revealed overall positive reactions towards video connectivity by younger adults and mixed reactions by older adults. The design for the volume mechanism did not work as expected for both groups. The interventions also brought out opinions and conformity dynamics within groups of older adults and attitudes by younger audiences towards older people. More research is needed to understand these reactions and attitudes in comparable contexts.

1. Introduction

Digital connectivity plays a pivotal role in many people’s lives and its uptake is increasing. A total of 77% of Europeans use the Internet at least once a week and 65% of Europeans do so every day or almost every day [] (p. 4). Forty two percent of Europeans use social media every day or almost every day []. Pew Research [] reports that 100% of Americans age 18–29 years use the Internet, and 96% of this age group owns a smart phone. In comparison, only 67% of American adults over 65 years use the Internet, and even fewer (42% of those who access the Internet) report owning a smart phone []. However, technology use and digital connectivity is still limited for adults over 75 years of age. For example, in the United States, 44% of adults aged 80 and above use the Internet and 17% of this user group own a smart phone []. Whilst in the U.K. 53% of adults aged ≥75 years old report not to use the Internet at all [].

Digital connectivity has many benefits [,,,], one of them is to support contact with relatives and friends [,]. The advantages of maintaining social contact are particularly of interest to the older user group, who are more at risk of being socially isolated [,,]. Social isolation is defined by a lack of quality and quantity of social ties as well as low social participation and support [,]. Although risks of social isolation in younger generations will also continue to exist despite technology, the differences in user and usage numbers indicate a potentially greater issue, namely, the segregation between communication channels and user groups. This lack of interaction between user groups is likely to feed into the age segregation/ageism cycle [,,].

A considerable amount of literature has been developed around the topic of the digital divide [,,,,,], digital spectrum [], or grey divide [], which discusses the disproportional distribution of digital technology usage within populations. The following Section 1.1 discusses the concept of the ‘digital divide’ to highlight the importance for an ongoing debate and need for more contextual research that this paper provides an example of.

Disadvantages of being digitally disconnected include lack of information and communication, restricted access to services, and missing out on economic advantages [,].

Older adults are not a homogenous group and vary highly in their abilities and circumstances despite the same age in nomination [,,,,,]. Reasons why older people choose not to go online or let usage lapse appear to be due to a lack of perceived benefits, interest, skills, or knowledge and access [,,,,,,]. Moreover, technology adoption by this age group seems to be based on a complex set of interrelated factors concerning social, attitudinal, and physical circumstances, as well as digital literacy and usability of the technologies [] (p.1).

It is now well established that online video is one of the benefits of digital connectivity to support contact with relatives and friends []. Research shows how video calling is especially of benefit to families who live geographically far apart [] and how video calls allow for virtual family visits with a sense of actually being there [].

It is further well-known that the group of older adults is growing in the western world and Asia, with the oldest group (80+) being the fastest growing demographic group globally; it is projected to increase threefold from 137 million in 2017 and to 425 million in 2050 []. However, this group compared to younger older adults (people aged 65–79) are more likely to be unhealthy and institutionalized []. Despite its growth, there has been little research conducted to understand their experiences, barriers, and enablers associated to their digital interests [,], which is frequently due to access, recruitment, and consent [,,].

Research in the disciplines of design research, Human Computer Interaction (HCI), gerontology, and gerontechology has highlighted the issue of digital technology adoption and frequently argued for participatory approaches to the design process to ensure the target audience is understood and feels involved [,]. However, it has yet to be fully established in what way co-designing processes influence the actual use of technology later on [,].

The number of research studies on the topic of older adult users has considerably increased since 2010 []. Although a large number of research still takes place in labs or only with user involvement at certain points of the design process, there is an emerging trend of research, which involves older adults with technology use in real-life context [,,,,] or in the making or designing of digital technology [,,,]. With new approaches such as vignethnographes [], netnography [], and extended group interviews working with a key informant [], as well as established approaches such as observation, the relationships between (older) users and real-life context has been examined from buying train tickets at Austrian ticketing machines [], taking part in digital exercise games [], googling (health) information [], and to comparing family solidarity by information and communication technology (ICT) usage in two different countries [].

This paper introduces a form of community gerontology and co-production by describing real environmental design research interventions using online digital video. The author employed a constructivist design research approach involving older and younger participants in real-life settings [], which is also called ‘in-the-wild’ research in the discipline of HCI. When conducting this type of research, ‘embodiment’ is a key concept for the experience by the participants as well as by the researcher. Embodiment is “concerned with the social and physical context of the body in structuring cognition and how the world is experienced” [] (p. 60). Capturing the experience, attitudes and challenges in situ of the intervention can reveal insights and dynamics between people, technology, and context, which otherwise may stay hidden with more traditional research approaches.

The term ‘dynamics’ in the context of this paper is employed to describe the evolving action processes within a system and it refers to the concept of “social life as dynamic streams of action with social interaction instead of mental calculation as the mechanism through which it [the social life] proceeds” [] (p.1103). In the context of this paper, ‘communication’ and ‘interaction’ are defined through the way in which the authors of [] refer to a single communicational unit: “a communication” and to a series of messages exchanged between persons as “interaction”, whilst collaboration occurs when two or more people are handling a common object whilst exchanging messages [].

This paper is distinctive because it provides an account of employing a constructive design approach by initiating a co-design and co-produced approach, in addition to reporting the embodied knowledge gained through interventions. The use of the term intervention derives from a social science perspective as it is employed akin to an action research approach, where the process is to identify a problem and to design an experimental intervention to gain insights into the problem or to solve it. The work presented in this paper is of interdisciplinary nature. It intersects at the fields of design, social sciences, gerontechnology, gerontology such as environmental gerontology and community gerontology, interaction design, and communication studies because it elicits reactions from population groups, which otherwise do not mix naturally due to social segregation []. It will predominantly be for the benefit of design research (due to the description of the artefact and design process) and gerontology. Given the interdisciplinary nature of this work, it will also support bringing organisations, third sectors actors, and academia together to learn about design techniques and processes, as well as about how people understood and appropriated the artefact and the interactions carried out []. Contributions of this research can be understood as one small step towards establishing a policy for creating “spaces where young, middle-aged and older people from all walks of life can get to know each other enough to build mutual respect, develop cooperative relationships, and reignite the norm of human-heartedness” [] (p. 332).

1.1. Disussing the Digital Divide

The early common misconception of the digital divide was a rather simplistic dichotomous model of people who have and have not access to information and communication technology (ICT) in the information society []. The study in [] examined theoretically the origins of the digital divide and traced it back to the centre-left social inclusion policy agenda of the 1980/1990s. The author of [] found the different access levels to ICT in the population reflected existing social structures, where typically the privileged experienced more benefits. He called for the political recognition that crucial issues of the digital divide are not just technological and cannot simply be overcome by providing everybody access to ICT. The study in [] took stock of 5 years of digital divide research (2000–2005) and discussed the four successive types of access: motivational, physical, skills, and usage. The author of [] observed a shift of attention from physical access to skills and usage.

In 2002, Lenhart & Horrigan [] reviewed data collected by telephone survey and focus groups (n = 2745) through the Pew Internet Project []. The authors [] developed with the results a model to indicate that ICT use consists of a spectrum of non-users and users, which is made up of broadband users (13%), uninterrupted dial-up users (20%–30%), intermittent users (16%-28%), net dropouts (10%), net evaders (8%), and truly unconnected (24%).

Additionally, in 2002 a government initiative provided the infrastructure for a whole town of 27,000 inhabitants (9000 households) near Atlanta. Working with data from the post implementation survey, [] examined the planned use of ICT, in this case internet access provided through the television set. The authors of [] analysed 451 usable responses (sent to 3500 households), which represented two population groups, the socio-economically advantaged and socio-economically disadvantaged. The study in [] found that the advantaged group had a higher tendency to respond to personal network exposure, whereas entertainment represented a key factor in motivating the disadvantaged to use ICT. The study in [], similar to that of [], concluded “even when technology is made available, disadvantaged individuals still need to deal with psychological and material barriers that are not addressed directly by technology centred interventions” [] (p.112). Although this research worked with a fairly large population sample and was well structured, there were limitations. One point of criticism can be given around the issue of accessing the Internet only through the TV set. Families could not watch and use the Internet at the same time. Undoubtedly this competition between the two media will have had an effect on the usage, considering the role of TV watching in each of the population groups.

The researchers in [] performed secondary analysis of Eurostat survey data, which focused on the member states of the European Union. The data included the daily use of computers for the last 3 months and the average use of the Internet at least once per week. The authors of [] examined two main dimensions of the digital inequality, which were skills (level of formal education was selected as variable of the skill dimension) and autonomy (population density was selected as variable). Results showed that northern European countries employ more intense use of ICTs than the southern part of Europe. In particular, Greece seemed to have low percentages in terms of the daily use of computers and the average use of the Internet. At the time of the research of [], the authors stated that Greece’s network infrastructure still needed to be improved, and that their education systems needed to be modernised. The authors stipulated that internet and computer use was higher in northern parts of Europe because there was higher family income, younger people were more quickly introduced to ICT at school, there were more effective and efficient ICT training systems, and was better developed network infrastructure. This research only looked at one type of access and only with secondary data, it could not offer more insights in why people in southern Europe use ICT and the Internet less than northern Europeans.

The study in [] examined the inequalities using the Internet and ICT between age groups, with special attention given to the oldest members of society. A representative random sample of a total of 1105 Swiss seniors were interviewed either by phone or with a paper questionnaire. Statistical analysis showed that gender differences in usage disappeared when other variables were controlled for, and that social contact has manifold influence on internet use. The study in [], like the study in [], found that encouragement by family and friends are a strong predictor for internet use. The study in [] suggests that the access divide is the first gap, yet it is an important gap for 70 plus year olds because lack of access and further hurdles such as the specific use and retained use of applications and software still exists.

The authors of [] analysed general patterns of access and ICT literacy of Swedish citizens aged 65–85 years old. A postal survey was sent to 2000 Swedes, and 1264 respondents filled in the questionnaire digitally or sent it by mail. The study in [] found a positive correlation between levels of material, discursive and social resources, and access to ICT, which indicated that with a greater amount of resources, the average number of ICT devices increased. Furthermore, the study in [] found that with increasing age, economic (e.g., income), discursive (e.g., English language skills), and social (e.g., social network) resources decreased, which furthermore implies a decrease in access and literacy. It needs to be noted that ICT literacy is not like conventional literacy; in contrast to conventional literacy, ICT literacy needs to be updated regularly because technology keeps on changing interfaces and functions.

The last two studies, [,], were carried out in northern European countries, which are already highly adapted to ICT and internet use. It would be interesting to see how southern European countries compare with their older population (70+). Overall this discussion of the literature demonstrates how the debate around the digital divide has moved on from rather simplistic distinctions to more sophisticated models of analysis. The author prefers referring to unequal access and use of digital communication technologies rather than the term ‘digital divide’.

In the author’s view, this digital inequality frequently mirrors the structures of inequalities in society, which includes a generational issue, as with age, the resources to access digital media such as the social network of technology users, income, and cognitive abilities are more likely to decline. Furthermore, the unequal access and use of digital technology is shifting with time and with the development of newer technologies and software (e.g., mobile phones to access the Internet has overtaken the desktop computer). Therefore, continuous research is required to understand the changes in access and use, but not only with research addressing numbers of use, but also with qualitative and contextual research to understand the complex social exchanges and attitudes around digital media use or lack of use. This paper provides such an example by having built a digital research tool to connect different age groups and locations in real-world environments and by involving participants in interacting with it.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aims and Objectives

The aim of this research was to design an artefact that could support online social interaction for and with older people. There were two research questions involved in building the Teletalker artefact (TT):

- How could the benefits of online video connectivity be demonstrated to older adults?

- What type of interface and interaction mechanisms in the artefact are intuitive to older adults?

After building the TT artefact, as it is described in Section 2.3 and Section 2.4, the author conducted three rounds of in-the-wild interventions in the U.K., which will be described in Section 2.5.1.

The research questions for placing the TT in-the-wild are:

- How was the TT concept received by the audiences and did they use it? (social science level)

- Was the hand mechanism intuitive to switch the sound on? (engineering level)

- How did the TT in-the-wild interventions involve people in the design of online social interaction? (design level)

The following sections describe the theoretical underpinning of the research, then the research tool before continuing with the research procedure for the in-the-wild design interventions.

2.2. Theoretical Underpinning

Constructive design research (CDR) [] was chosen and implemented to move away from Frayling’s three categories of ‘research for design’, ‘research about design’, and ‘research through design’ []. CDR builds on exemplary design research [] and involves the construction of an artefact, which can be anything externalized such as a prototype, a system, a space, product, or a service and is employed in some form of workshop, intervention, experiment, or evaluation (the latter could also be an exhibition).

CDR has its roots in the fields of engineering, social sciences, art, and design and is divided between three places of research: the laboratory, the field, and the showroom. CDR uses the steps of firstly iteratively planning, secondly acting either by producing the artefact and/or by carrying out a form of evaluation, thirdly observing, and fourthly reflecting whilst drawing from interdisciplinary knowledge [,]. The author’s application of constructive design research for the TT research involved the making of the artefact (which is described in Section 2.3 and Section 2.4) and placing the artefact in the wild, where it was used as a ‘tool’ to elicit reactions in a similar manner to technology probes []. The interpretative process is described in Section 2.5.3. The author would like to emphasize that the nature of research with design research interventions is context-dependent and returns are not repeatable, even if interventions are carried out in similar conditions. Some noteworthy examples of constructive design research interventions are Dunne and Raby’s [] DesignNoir: the secret life of electronic objects, photostroller [], the CoMotion bench [], the Megafobia V-armchair thrill seeking intervention [], and Blythe’s [] ludic engagement activities in a care home. The latter included the video window, which supports the fifth design principle for the TT in Section 2.3. The benefits of such an approach entail explorations of nexus of experiences and potentially uncovering new connections in an imagined as well as in the real world, externalization of critical thinking, mutual learning for persons involved, as well as the development of new questions [,,].

2.3. The Research Tool – the Teletalker (TT)’s Design Principles

The author iteratively planned the making of the artefact by sketching and researching materials and interaction mechanisms. The latter was done by the author by researching online, speaking with experts, and by physically trying different combinations, that is, tinkering []. The TT artefact was built in response to the theoretical framework, which was developed in order to answer the first two research questions. The theoretical framework underpinning the TT was based on eight principles derived out of the literature from a range of disciplines such as HCI, philosophy, sociology, psychology, and design research:

Firstly, the TT installation served to create a social space [] in a public and safe place providing a platform for interaction (rather than a service that required to be used), which could also be described as an online presence system.

The second principle embraced the idea of people spending time in groups. The space around each TT kiosk allowed for usage in small groups [] rather than a single person using the digital system at home. This meant a novice user could try the technology together with someone more experienced, and this in turn could remove potential first time anxieties and create shared experiences.

Thirdly, the TT concentrated on only a few simple interactions (in this case the view, the mechanism to switch volume on and off and the potential subsequent face-to-face (video) communication) to draw out one of the major benefits of online connectivity []. By concentrating only on the video connectivity, the author aimed to avoid overwhelming the novice user with numerous interactions options.

The fourth principle was based on familiarity. Using the analogy of TV watching, an activity everybody is familiar with, it avoided stigmatization [,]. Stigmatization occurs when the person using it feels different to other people by having to use the technology []; therefore, stigmatization leads to low technology adoption rates [].

The fifth principle was based on feeling instantly rewarded rather than going through the effort of having to learn a new system []. Even without interacting through the TT, the digital view can be described as instantly rewarding [,].

The sixth principle aimed at intrinsic motivation. Having a (novel) view feeds into playful intrinsic motivation and curiosity and conversations play into humans’ need to be nurtured and have a sense of belonging [,].

The seventh principle included playfulness. The view, the volume mechanism and potential interaction allowed for ludic engagement or interpassivity. The latter is a term used by [] to describe an older adults’ interest in potentially interacting, but it appears as passivity from the outside.

The eighth principle for the TT was for it to not to be equipped with explicit information on how to use it, or anything similar, in order to invite reaction and interaction [,].

Designers deal with wicked problems and employ abductive thinking in the development of their artefacts []. For example, when designers plan to address the topic of loneliness or social isolation, they find themselves in a specific conundrum where they cannot explicitly design for this, as being ‘lonely’ is generally perceived as a taboo and no one would like to be exposed as being lonely. The author on the one hand aimed to design the TT to be usable by anyone without digital literacy skills, which are predominately older people, but at the same did not want the TT to appear as a ‘design’ for an older person. Furthermore, the TT system aimed to be attractive and enticing for younger audiences too.

Many social interactions are born out of everyday interactions such as gardening, shopping, or walking the dog [,]. These everyday interactions provide people with opportunities to talk, which can also be seen as a ‘ticket to talk’ [,]. Considering these opportunities, the author saw the TT design interventions as an event itself, which could have been the provided ticket to talk through the TT to initiate conversations [].

2.4. The TT Technical Set-up

The setup of the TT artefact consisted of two wooden cased kiosks, each showing a large monitor, but hiding the computer and other peripherals to reduce complexity and to focus solely on the digital video connectivity.

The two kiosks were connected to each other using Skype, which was constantly on and provided a view into the other location, that is, the kiosk screen acted like a window into another world. The author chose Skype over other software options for video connectivity (e.g., Ovovoo, Googlehangouts) because it was able to be set to full-screen without any distracting frames or icons. The author later worked on bespoke presence software for the TT, but this was not the focus of this paper, although more could be found here [website] http://www.teletalker.org/>.

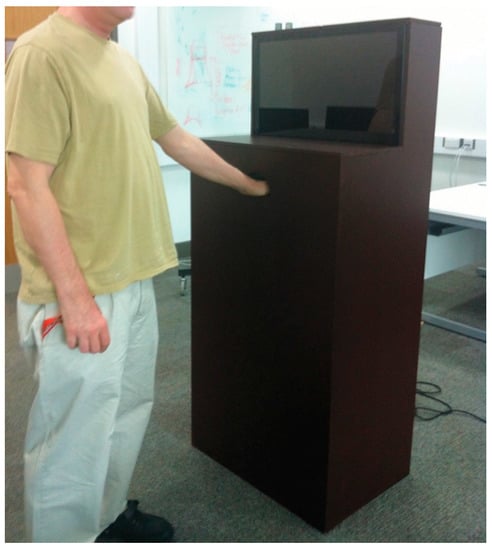

The two 27 inch screen computers ran Skype (muted by default), an arduino sketch, and Processing (a Java based programming language). Attached to the computer was the arduino board, to which a light-dependent resistor (LDR) and a 270 ohm resistor were connected. The analogue sensor, the LDR, constantly took values, and the arduino sketch fed values to Processing. When a person’s hand covered the LDR, the values decreased and Processing unmuted Skype to allow conversation (see Figure 1). As soon as the hand was taken out of the hole of the TT (and the LDR uncovered), Skype was muted again.

Figure 1.

A person demonstrating height of the Teletalker (TT) kiosk and use of the volume mechanism. When a person placed their hand into the hole, the volume was turned on. Permission granted by Dr Marianne Markowski.

The kiosks were painted chocolate brown to be reminiscent of the style of a 1930–1950 TV set such as the 1936 TV Baird T5. This TV analogy was employed in communications around the design research interventions because people of any age were likely to be familiar with TV watching.

2.5. Procedure

The following section describes firstly the locations, durations, and contexts to the in-the-wild design research intervention; secondly the type of participants involved; thirdly the data collection methods; and lastly the approaches to data analysis.

2.5.1. The Three Design Research Interventions

The author carried out three design research interventions by placing the TT kiosks in three different contexts for connections.

Intervention 1 consisted of a 4-day-long design research intervention to video-connect a day centre by a major charity supporting older people with the entrance hall of a university (see Figure 2). The aim was to connect younger people (i.e., students) and older adults (day centre clients) by providing a window into each other’s world. The researcher’s expectation was that the TT was intrinsically curiosity evoking and people would like to try it out without much prompting []. Furthermore, the author expected people to talk about the TT as a ‘ticket-to-talk’ during the intervention [,].

Figure 2.

The TT kiosk at the university’s location in the main entrance hall. The TT provides a view into the day centre. Permission granted by Dr Marianne Markowski.

Intervention 2 comprised a 5-day-long design research intervention to video connect a university café (see Figure 3) with another part of the university, which meant connecting people of any age who visited these respective areas of the university. The purpose of this round of design intervention were to see whether the improved hand mechanism and signage were working and whether the TT proposition was curiosity-evoking for people to try it out in this setup. During this intervention, the TT kiosks were switched on and frequently left without a person manning them as a potential conversation partner.

Figure 3.

TT kiosk at the university’s cafe. A research aide communicates through the TT with students. Permission granted by Dr Marianne Markowski.

Intervention 3 comprised a 1-day-long design research intervention (just before Christmas) to video-connect two day centres of the same charity with each other (see Figure 4). This meant connecting two comparable groups of older people. This intervention was timed to take place just before Christmas so that the purpose for the TT became the opportunity for visitors and staff of the day centres to wish each other festive greetings and to admire each other’s decorations.

Figure 4.

TT kiosk at day centre 2. The TT kiosk shows a view into day centre 1. Permission granted by Dr Marianne Markowski.

2.5.2. Recruitment of Participants

The participants of the in-the-wild interventions were mostly at random and self-selected depending on the locations where the TT kiosks were placed. In the first intervention, participants were clients from the day centre (location of one of the TT kiosk) and students, university staff, as well as visitors who specifically came to see the TT at the university location. Day centre clients were regular visitors of the centre and who were given lunch whilst on the premises. The majority of the day centre clients were female, over 75 years old, with no computer experience and had some type of mobility impairment. There were two groups of clients, the first visited Tuesday and Thursday, the second Wednesdays and Fridays. Each group comprised around 35-40 clients. In this respect, there was a total of 80 potential TT users who were day centre clients and around 10 day centre staff or volunteers who were working there while the intervention took place. A minimum of 11 participants interacted directly and communicated through the TT with students or staff at the university’s location.

The university had a total of 23,000 enrolled students, however, not all students were always present on campus. The TT was placed in the main entrance hall of the main building, where students and staff could find seating areas, an information desk, and a café. At busy times, the entrance hall could easily accommodate several hundreds of students and staff. A minimum of 25 participants interacted directly and communicated through the TT with day centre clients or with research staff.

The second intervention took place in the Art and Design building of the university. At peak times, the café served around 60 people (with seats). The second TT kiosk was placed in the hallway on the second floor. There the footfall of students and staff was considerably less, possibly not more than 50 people throughout the day. During this intervention, at least 32 participants (students or staff) interacted directly through the TT.

The third intervention connected two day centres for 1 day. One centre was from the first intervention, the other was about 3 miles located from the first. The second centre also had an average daily attendance by 35-40 clients; all mostly over 75 years old, with no computer experience, being mainly females, and having some type of mobility experience. Similar to the first intervention, there was a total of 90 potential users (day centre clients and staff); however, technical issues made it impossible to speak through the TT, and thus approximately 20 participants (mainly staff) interacted through the TT by waving and using gestures.

2.5.3. Data Collection

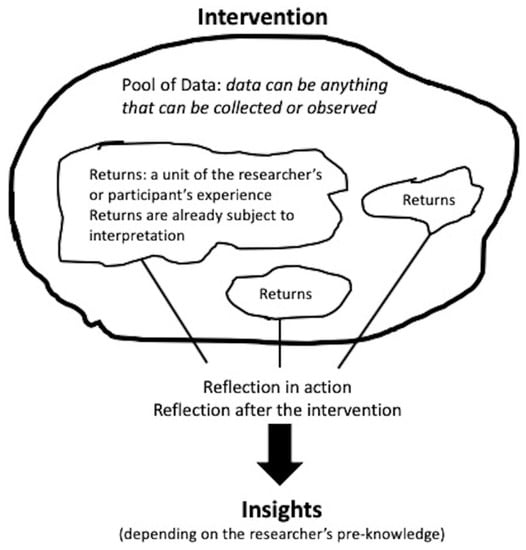

During each of the design research interventions, the author collected returns, which were clusters of direct feedback, notes, observations, and reported experiences (see Figure 5). The returns were captured in a form of personal note taking, reported peer observations, feedback sheets, as well as exit interviews after the use of the TT and video recordings of TT use with consent by participants. The term returns (akin to probes [,,,]) was chosen because data collection in-the-wild is complex and the aim was to gain insights rather than collect facts. The author could not claim that the notetaking was complete or exhaustive. Often, it was not clear which returns were of relevance until after the intervention and reflection had taken place.

Figure 5.

Diagram to visualize the relationship between data and returns. The researcher experienced the pool of data and collected returns whilst applying reflection-in-action and reflection after the intervention to draw out insights.

Knowledge and insights around the research were gained by simply being there. The author also had to apply reflection-in-action when dealing with technical problems or other unexpected events. Because design research interventions are resource intensive (people, material, and time) the author had different forms of data collection opportunities with each intervention.

In the first intervention, the author had support to conduct video recordings with participants, held conversations with users before and after using the TT, gathered impressions, took photographs, and collected observations by others. In the second intervention, the author had little support and was only able to observe and interact with people through the TT herself. The author further held conversations and prompted students to interact with each other through the TT. Feedback forms were also left with the TT kiosks.

For the third intervention, the author had access to research aides, who could interact through the TT as a conversation partner (if needed), teach participants about using the hand mechanism, and explain the TT concept. The author further prepared feedback forms to be filled in and held some conversations with potential participants.

2.5.4. Data Analysis

After each intervention, the returns were collated and the author reflected on them. Each cluster of returns was categorised into the following three aspects (social science, engineering, and design; similar to []), addressing the three research questions as stated in Section 2.1:

- Social science: returns on use and behaviour by people as well as users’ attitudes and motivations;

- Engineering: returns on suitability of the technology, natural interaction, and affordance of the volume mechanism;

- Design: returns on inspirations for future placements, applications, feedback on forms, and style improvements.

A full list of returns with aspect groupings and interpretations by the author can be found in Appendix A.

Seven video recordings of conversations, which had taken place through the TT, were analysed using a thematic coding approach [,] (p.475ff). Using Inqscribe software to transcribe the video recording, deductive analysis was first applied by looking for conversation content about the TT (i.e., the ticket-to-talk concept), and then inductive analysis was carried out by searching for patterns such as introduction elements and questions which going beyond small talk. Grouping the results together on the basis of the elements of the conversations established four themes:

- Conversation about the TT itself (i.e. ticket to talk concept);

- Small talk;

- Reminiscence;

- Future-directed personal questions.

2.5.5. Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was granted by Middlesex University’s Arts and Education Ethics Committee on 6 June 2012. A supplementary file is supplied, evidencing the approval.

3. Results

Results from the design research interventions were manifold, addressing the different aspects (social science, engineering, design) that are presented in more detail with each intervention below. These results also implicitly addressed the design principles on which the TT was based. Overall, it can be said that the design principles one and two—these being the having of a digital social space in a public space that could be used in groups—was positively confirmed during the interventions by attracting some groups of older adults to the university location and by research aides supporting day centre clients using the TT.

Furthermore, the concept of connecting two disparate places and having a view into it without having to learn much new technology was intriguing for the vast majority of participants (design principles three, four, five, and seven). However, when information around the context was not sufficiently provided (design principle eight), the TT kiosks attracted less interest and even a rejection by older participants. Considering the lack of the context information and an explanation on how to use the volume mechanism, design principle six was also not successfully externalised.

Nevertheless, the view into another space, especially in the first intervention, educated participants at the university location about day centres. Furthermore, the interventions elicited some reactions and attitudes towards older people, which could be labelled as ageist. Non-verbal communication took place through the TT, such as waving between participants, mostly when participants knew each other. Any verbal communication through the TT was predominantly small talk and not about the TT, as originally expected by the author. Technical problems overshadowed the experience of the TT, whilst it became clear that the hand mechanism was not intuitive for any person of any age. The following individual results sections (Section 3.1, Section 3.2, and Section 3.3) start with returns addressing the social sciences aspects first, then the engineering and design returns. It needs to be noted that some returns fitted into several aspects; the full list of returns with groupings and interpretations can be found in the Appendix A - for the 1st intervention: Table A1, for the 2nd Intervention: Table A2 and Table A3 and for the 3rd Intervention: Table A4.

3.1. Results of the First Intervention – Connecting Younger People with Older People

The returns show a mixture of reactions towards the TT on both locations (social science aspect). The concept of providing a window into another location and thus demonstrating the benefits of digital video connectivity seemed to have worked (design principles three and four). The view into another space made people curious, and several returns reported people waving to each other through the TT (design principles six and seven). Returns showed that university staff and students learnt about the ‘inside’ of a day centre and what kind of activities older adults do there (design principle five).

Participants at the day centre were informed about the research through their newsletter, notices on the door, as well as the day centre management team promoting the intervention through conversations. Those who felt informed about the research did not object to the TT, and some took part in conversations with university staff and students. However, one day centre client questioned why they were connected to a university. In her view, she felt that she did not have anything in common with students, which meant that design principle six did not apply to her.

On day two, one particular day centre client, who had been on holiday, did not feel informed about the research and objected to it. Her view negatively influenced the opinions of other day centre clients on that day. The dynamics in this group changed from previously not commenting on the TT towards expressing negative feelings about the TT. The TT was labelled “big brother” and a “ghastly thing”. Due to these reactions, the TT was moved to the hallway of the day centre for the final day of research.

Without any signage, the author found that people at the university location were very unlikely to approach the TT nor the research team (design principle eight was not working). Even after signs were made, the research team had to be present and actively invite students or staff to try out the TT and elicit their reactions, with the exception of some older female participants who came to the university’s location because they were informed through the charity’s newsletter about the TV-like artefact through which one could speak (see Figure 6). In the author’s conversation with these women, who were all members of a local community club, it became clear that they differentiated themselves from the day centre clients “as still fit”, which implied a belittling attitude towards day centre clients, who had less abilities and independence than they did. Another notable attitude observed was held by two young students, who came especially to see the “old dudes” by looking at the TT screen and which they found “cute”. These students, however, did not choose to speak through the TT with day centre clients nor with our research team; they stood nearby for a little while to look at the screen before moving on.

Figure 6.

Three women (to the right of the TT) from a local community club using the TT. The three older women from the community club came to try out the TT because they had read about the ‘Talking TV’ in the charity’s newsletter. Permission granted by Dr Magnus Moar.

The returns showed that the hand mechanism was not intuitive (engineering aspect), whereas the view was intuitive. This meant that the third design principle only partly worked. Most people expected the sensor to act as a switch rather than a contact point. The mechanism was learnable, but due to unfamiliarity, the mechanisms’ affordances [,,] were unclear.

Regarding returns on the design aspect, participants at the university site were willing to share ideas on future users of the TT (see Appendix A Table A1: Returns 4, 9, 10, 13, 21). Some of the students suggested employing the TT in the service and information industry (e.g., train time information, John Lewis Department store, McDonald’s drive-thru), to connect different countries, switching views and camera angles. The style and look of a jukebox were proposed and included modernizing the look and feel of the kiosks because it is something that young and old are familiar with (addressing design principle four).

Members of the local community club imagined their club connected with places such as the library or other clubs to share what they do. Day centre clients, who had tried the TT, did not offer any design suggestions. However, some of the day centre staff suggested connecting the kiosk to public places such as the library to provide a view into another public place where people of different ages gather.

TT Conversation Results

Results focusing on the TT conversations collected a total of 27 conversations, with 17 conversations taking place between the research team members and the day centre clients. Eight conversations took place between students and the day centre clients with a further two conversations between a university staff member and day centre clients.

However, only seven conversations were video recorded and subsequently analysed using the thematic coding approach [,]. Results showed that the idea of the TT as a ticket-to-talk in itself did not work (only two instances were recorded, and these instances were prompted by the research team member). Conversations consisted of mainly small talk where the social elements such as people laughing and smiling at each other to build a rapport were more important than the content []. Small talk was the largest category and theme; it included asking for each other’s name, asking about the day and how one feels, observing the environment, bringing up universal topics such as the weather, and looking for common interests. Usually the younger member in the conversation would ask the initial questions. One example of a TT small talk conversation is presented here:

Member of the research team: Are you here tomorrow?Day centre client: Tuesdays and Thursdays.Member of the research team: Tuesdays and Thursdays.Day centre client: Yeah.Member of the research team: No, am going back home tonight. I’m not living in London.Day centre client: Ahh.Member of the research team: I’m living in France.Day centre client: Oh you’re lucky the weather is better there.Member of the research team: Whoa, in the north of France it’s just like here, isn’t it?Day centre client: Ah (chuckle).Member of the research team: It’s near Lille. Have you been to Lille?(inaudible)Day centre client: Aw that’s better.(inaudible)Day centre client: Sunny June, but I don’t know what happened this month.Member of the research team: (chuckle).Day centre client: Turned out all that horrible.

Furthermore, in the analyzed conversations, there were two instances of reminiscence; one referred back to what had been on the site where the university was built now and the other was about the client’s experience arriving in London when he immigrated. There was only one instance of a future-directed personal question asked by a day centre client to a student, when she asked “Will you get a job when you have finished?”. Overall, day centre clients asked only a few questions, which fell into the theme of small talk such as “what is your name?”, “aren’t you tall?”, and “how do you do?”.

3.2. Results of the Second Intervention – Connecting Younger with Younger People

The second intervention aimed to verify the TT concept to work as a tool for evoking curiosity and playful interactions between young people (design principles six and seven). At this stage, the hand mechanism had been improved to work more smoothly and instructions were added onto the kiosks on the basis of previous feedback and observations from the first intervention. Loudspeakers were implemented to improve the volume levels.

Social science and design returns showed that there was positive interest in the concept of connecting various university locations visually, as well as connecting disparate places such as a mosque and a church (See Appendix A Table A3).

Although in the previous intervention students appeared more curious than older audiences in wanting to try out the TT, it became clear that the TT kiosk alone did not entice people to come and interact with it, which meant that design principle eight did not work to entice people to explore the TT. A potentially interested person needed instant feedback when using the TT, for example by someone waving or speaking, otherwise the person chose not to continue. Social science returns showed that people appropriated the TT for their own needs; in this respect, design principle eight worked, as it gave users the freedom to appropriate. One example is a member of staff who praised the existence of the TT on the second floor because it was a tool for him to check the length of the queues at the café (see Appendix A Table A2: return 4). Some students communicated non-verbally through the TT by holding up messages, which left the author wondering whether sound was needed at all.

Despite available instructions on the hand mechanism, the engineering returns made clear that the mechanism was not intuitive, but that instead it restricted participants’ gesture movement because they could only use one hand while speaking. Furthermore, intermittent issues of poor sound quality remained, alongside background noises, which had a negative effect on the overall experience.

3.3. Results of the Third Intervention – Connecting Older with Older People

On this particular day, technical issues resulted in the volume mechanism not working efficiently, and the TT could only be used for a visual connection and mainly social science returns were collected. This visual connection was positively received by the day centre 2 staff, who were very pleased to wave and mouth messages to fellow staff at the day centre 1 Age UK Barnet – Meritage Centre. This confirmed design principles one, two, three (the view only), five, six, and seven. However, the day centre 2 clients seemed less keen to approach the TT and wave to fellow clients at day centre 1.

The author held conversations with some of the day centre 2 clients. The author learned clients were not keen to interact with the day centre 1 clients because they felt that day centre 1 had received more attention in regards to resource allocation such as more exercise classes (see Appendix A Table A4: return 2.). At the same time, at day centre 2, two clients who had previously experienced the TT waited patiently to use it again and were disappointed when they found out that the sound was not working (for these two participants design principle six and seven seemed to have worked well).

Due to time constraints, the author was not able to address the issue of the non-intuitive hand mechanism, other than making sure that a research team member at each location was always present to be a conversation partner and to assist with the use of the hand mechanism.

Although feedback forms were prepared, it became quickly clear that these were not useful, because of at least two reasons. Reason one was that the technical performance clouded the overall experience of the TT and reason two was that day centre clients had difficulties (poor vision, tremor, wrist pain) and therefore a resistance to filling in paper forms by themselves.

4. Discussion

This paper presented the constructivist research approach and the research tool employed, as well as the context, setup, and the results for the design research interventions.

The results listed above demonstrate the multi-facetted nature of returns gained during this type of real environmental research. The following section discusses some of the returns, which are likely to be of interest of this readership. Namely, the reactions towards the TT and how the concept of a window and “talking TV” was received; secondly, attitudes and dynamics between similar and disparate groups; and finally the intuitiveness of the TT interaction mechanism. Readers should bear in mind that all the returns collected were bound to the context of the design research interventions and would not have not occurred in the same way if the setup had been simulated in a usability lab, for example.

4.1. Reactions towards the TT

The first intervention was the most ‘educational’ connection of two different places. Staff and students learned about the activities taking place in a day centre, the type of adults visiting and working there, as well as the look of the interior. Even without interacting with day centre clients, university participants had a view into it. At the same time, only few day centre clients showed explicit curiosity about students and university staff by trying out the TT. Other everyday centre clients did not seem to feel enticed this way. The latter supports research findings where older adults do not engage with technology if they do not perceive it as beneficial, and develop negative attitudes towards it with increasing age [,,,].

In particular, one client felt uninformed about the research and developed a negative attitude towards the TT as feeling overlooked, similar to the concept of ‘big brother’. Here, it seemed that lack of information about the research intensified the negative attitudes towards the digital video technology. Research around attitudes towards telepresence robots argues that prior experience of telepresence artefacts can influence attitudes and potentially reduce anxiety [].

At the same time, at the university location, students and staff did not appear to be concerned about the ‘big brother’ aspect, which may have to do with the fact that they are more in contact with the ubiquitous use of screens in university buildings, but also by the omnipresence of Closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras and screens on buses and shopping malls [,,,].

Providing context around the TT interventions was important in order to attract and support interaction between people and for their experience of the TT. During the second intervention, it became clear that the view into the other place and the location of the TT were crucial to attract interest. As returns showed, there was an interest in connecting unusual places or locations useful for the service industry. Artistic interventions and telematic experiences such as the telecstroscope [], the ‘Hole in Space’ [], and ‘telematic dreaming’ [], which partly inspired this research, attracted intergenerational audiences and created a reciprocal feeling of presence. However, those interventions did not use an audio connection for the other location, an aspect that was important to the author of the TT because it gave participants some form of control; however, the necessity of this was questionable in hindsight.

The context information, which described the TT as a form ‘talking TV’, attracted some adults of the local neighbourhood. When participants at the university location tried the TT with the audio connection, they volunteered the ideas for uses of the TT such as help desks or information desks where a friendly face-to-face conversation for advice could be combined with remote locations. An applied example of this would be the First Ontario Union bank using a video calling facility for their ATMs [], as well as Barclays Bank, Nat West, and RBS having introduced a video calling banking service based on using an app in the U.K.

4.2. Attitudes towards and by TT Participants

As discussed above, not all day centre clients were interested in trying out the TT, nor were they interested in talking to students or university staff. This may already be the result of age segregation, where the interest in connecting with other age groups reduces through lack of contact with other age groups [,]. Some clients of the Tuesday and Thursday group were keener than others who attended the same days. The thematic analysis of the recorded conversations revealed that small talk was dominant. One of the uses of small talk is about finding a connection between the participants []. As this intervention setup was not connecting groups on the basis of their interests, but simply because digital technology made it possible and the connection was curiosity evoking, it was understandable that participants did not share any in-depth personal topics. Overall, it was observed that older adults asked fewer questions than their younger conversation partners. Whether this was due to the speediness in asking questions by younger conversation partners or founded on a lack of curiosity remains speculative. Literature around curiosity and age is sparse and yet divided, with some arguing that the level of curiosity does not change with increasing age [,], whereas more recent literature postulates that curiosity naturally reduces with age []. It needs to be noted that a unifying definition of curiosity does not exist to date and curiosity is often conflated with information- or sensation-seeking behaviour and showing interest [].

One participant objected to the TT being switched on, and other day centre clients seemed to follow this person’s opinion despite having been informed about the research previously. It seemed that group dynamics and thus group opinion and consensus were very much influenced by people with certain dominance. If these ‘gate-keeper’ day centre clients were not content with something, other clients would not speak against their opinion. The topic of group conformity has been examined in the literature mainly with regards to political attitudinal change [,,] and where group size matters as to whether a person is more likely or not to align their opinion with the group. There is further literature around the delicate balancing act a facilitator needs to perform when working with older adults in groups [], but literature directly relevant to the ‘gate-keeper’ observation, that is, where one person dominates a group of adults with their opinion, was not found. Certainly, group dynamics where some people show domineering personalities exists also in groups of students or working groups, but it appeared to be a more extreme case with the day centre clients. The latter had been discussed with the day centre management after the intervention.

Similarly, a negative attitude was expressed in the third intervention where day centre 2 clients did not to have anything to do with day centre 1 clients. Although it had nothing to do with the older adults per se, it was about the feeling that the other centre had preferential treatment (i.e., it received more resources). The feeling implied disinterest and thus resistance to take a look through the TT. One step up from disinterest to belittling and direct ageism were two returns noted in the first intervention. The women from the local community club differentiated themselves from day centre clients because they could still walk and were fit. With their comments, there was a belittling attitude towards the ‘poor’ day centre clients, who have to attend because they have no independence anymore. Although ageism is a common occurrence in people’s everyday life, it is an under-researched topic. North and Fiske provide a brief overview of extant theories explaining ageism on four levels: individual, interpersonal, evolutionary, and socio-cultural theories [].

This behaviour mentioned above by the local community club women could be explained with the Social Identity theory, which focuses on the relationship between personal identity and group identity, together with the need to feel positive about one’s group []. Another evolutionary theory on ageism considers ageism as hardwired in people, starting from a young age [,,]. This might explain the ageist commentary by the two young students who thought seeing “old dudes” was a spectacle and something to find “cute”. Although it was not meant maliciously, it was certainly objectifying the day centre clients into something else. This return leaves the author wondering whether the two students would talk in the same way about their older relatives or whether they were only prompted to see “old dudes” as “cute” by the TT intervention. However, [] reports that there are indications that ageist behaviours are less common in interactions with family members and friends than with others, and the authors argue that “in today’s Western societies, the family represents the only truly age-integrated social institution” [] (p. 354).

4.3. Developing an Intuitive Ineraction Mechanism

Every constructive design researcher faces the challenge of designing something that should be telling the user intuitively by form and shape what it can do, but users have never actually done any interaction with it before, especially not in in public. By the third intervention, it was clear that the hand mechanism to control the volume did not work for participants of any age.

In addition, due to volume functionality, many additional issues with the digital video technology occurred. The quality and speed of the sound was easily affected, not least by digital bandwidth issues at the day centre locations. Would a view-only connection (i.e., the screen only) be enough to demonstrate the benefits of digital connectivity? It was the intention to give control to participants by providing the hand mechanism and by letting them choose to speak or not.

However, the TT interventions in those locations brought out the fact that people seemed to enjoy communicating non-verbally (waving smiling, mouthing words) and by holding up messages. Having a view into another space appeared to be intuitive, although it needed contextual information as to where it was connecting to and why. The analogy to ‘a talking TV’ was helpful in order to communicate about the TT interventions. Nevertheless, despite the familiarity of the ‘TV watching’ concept, the analogy did not seem enough to easily convey the idea that one can talk through the TT as well (and how to use the hand mechanism).

4.4. Limitations of the Research

Several limitations should be considered concerning the scholarly work presented here. Design research interventions using two kiosks at two different locations are resource (time, material, and people)-intensive and prone to many real-world interruptions such as technical problems. This is likely to affect how the researcher and researching team can collect returns. For example, in the TT research, a difference in the form and amount of returns could be noted in the first intervention (observations, notetaking, but also video recordings), then second (mainly observations), and finally in the third intervention (mainly observations and conversations).

Additionally, and out of the author’s control, there was unexpected building work on the university site and the high noise levels made conversations through the TT difficult to hear. Furthermore, there were technical issues with the Wi-Fi connection and Skype in the first and third interventions, which did not help the conversational flow in the first and prevented any verbal conversation in the third intervention.

Because the ethics committee decided a member of the researching team had to attend the TT kiosk at the university location to protect the day centre clients from potentially misbehaving students, who could, for example, pull faces, belch, or get undressed in front of older adults, the author was more likely to collect returns from the university side than at the day centre, where someone was not always there to observe. The author held conversations through the TT with participants from the day centre, but this made note-taking difficult.

Additionally, due to the nature of the constructivist research, and where the researcher was present at the artefact, the Hawthorne effect as well as the novelty effect needed to be considered when reflecting on the returns.

Finally, the actual number of interventions with a fully working research tool and the number of participants directly interacting with the TT was comparatively little when considering the potential access to the fairly large number of students and day centre clients.

4.5. Proposed Recommendations

On the basis of the scholarly work presented here, several recommendations are proposed in a bid to move this field of research and engagement forward, by undertaking a series of future works:

- Consider undertaking a scoping review in order to synthesize existing and recently published work on intergenerational communication and digital video presence. Like the aforementioned art interventions [,,] operated without sound, it is questionable that hearing each other is necessary when these interaction points are placed in public locations. For communications scholars and gerontologists, but also for policymakers, it might be interesting to video connect, without audio, public intergenerational places such as plazas, shopping malls, or two separate parks in order to observe who and how people interact through the system (e.g., []).

- In addition, future work may wish to employ the TT kiosks (or a modified version) and place them where the context is specific and purposeful. For example, the TT kiosks could connect two selected groups, such as one of older adults and one of younger adults who share similar interests but could not easily travel to each other’s location. One idea could be to connect an arts and crafts club in England with an arts and crafts club in Wales. Creatives, media practitioners, and community workers would benefit from learning whether reactions towards video connectivity and attitudes towards older people are repeated or comparable in this context.

- Future work may consider undertaking a scoping review to synthesise existing and recently published work on intergenerational communication and ageism. As Drury et al. [] suggests, people live in an increasingly age-segregated society []. Knowledge needs to be synthesized in order to understand which strategies are effective to uncover and reduce ageist attitudes, as well as whether digital technological interventions such as YouTube, Facebook, and videogames [,,,] may help positive intergenerational communication, as noted by Marston and van Hoof [] across age-friendly cities and communities. Policy makers will benefit from learning about these strategies to break the age segregation/ageism cycle.

- Research approaches involving constructive design research or co-production are beneficial in uncovering the differing power levels of participants involved [,,] and discriminating attitudes held [] (p.8), and should be adopted more frequently by researchers in order to elicit knowledge and collaboration to enrich the variety of approaches applied in disciplines such as gerontology and communication studies.

- Future research employing constructive design research intervention it is beneficial to have a people-rich research team, consisting of researchers from various disciplines in order to help capture returns and interpreting the data from different perspectives and theories. When carrying out real environmental research, explicit attention needs to be paid to the information being provided before and after the intervention to entice, attract, and involve participants. Researchers may need to seek out the opinions of leading individuals to explain about the research intervention in detail to avoid unnecessary resistance to participation.

5. Conclusions

The design research interventions collected a variety of social science, engineering, and design returns, which implicitly addressed the design principles for the TT. Design principles one and two were successfully demonstrated by having brought the technology to younger adults and older adults at the day centres. By placing the TT system with older adults, who may not be computer literate, they experienced online video connectivity and potentially its benefits (design principle three). However, not all day centre clients experienced the benefits of the TT, mainly due to technical problems, lack of information around the interventions, and lack of interest to interact with people at the other location. The latter worked against design principles six, seven, and eight.

Having a view into another space was highly intuitive (design principle five). Intrinsically, it attracted curiosity by participants, especially if there was some ‘action’ to see on the screen (design principle six). At the same time, the TT kiosks also elicited negative attitudes towards being seen and was labelled “big brother” by day centre clients.

The TT kiosk hid all peripheral items and showed only the screen and one mechanism to control the volume. Hiding the complexity of the interface was well received (design principle three and four). However, the designed mechanism to control volume was not intuitive for older adults nor younger adults and would need to be improved.

This paper brought out the complexities of carrying out design research interventions in the wild, and the multi-layered information the researcher could gather in order to gain insights for future work. The research presented here is distinctive because it reveals reactions towards online video connectivity as well as attitudes and group dynamics between older adults and younger adults. The research intersects in the fields of design, social sciences, gerontechnology, gerontology such as environmental gerontology and community gerontology, interaction design, and communication studies by providing an example of constructive design research, which connected population groups that otherwise do not mix naturally. It specifically contributes to design research with the built TT system and the process of conducting design research interventions. The returns collected and experiences created with the in-the-wild interventions are likely to be of interest to gerontology and social sciences. Connecting disparate population groups who otherwise do not mix is of benefit in uncovering attitudes and group dynamics, which are important to know for policymakers, practitioners, and researchers so that further strategies to break down the age segregation/ageism cycle can be developed.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all my research team members for supporting me during the design research interventions, and all the participants and the charity that made the connections possible. I also would like to express my gratitude to Hannah R. Marston for guiding me with the development of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Collected Returns

Observation Type/perspective:

- Engineering (E)—comments and feedback on the mechanism or functionality of the TT.

- Social science (SS)—learnings around the people.

- Design (D)—aspirations and desires what to use the TT for, and suggestions on its form, look and feel.

(Note: not all returns fell neatly into one category)

Any names are shortened to one letter (e.g., M) and these were randomly assigned to assure anonymity.

Table A1.

Returns from the first in-the-wild intervention.

Table A1.

Returns from the first in-the-wild intervention.

| Day | No. | Returns | Type: Engineering (E), Social Science (SS), Design (D) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | 1 | I explain to the helper of the research team how the hand mechanism works. Although he listened, he thought that it worked like a switch where one puts the hand in to switch the sound on and the hand in again to switch the sound off. | E | Expected the mechanism to work like a switch (and not like a contact point where you had to leave your hand in there). |

| Day 1 | 2 | A member of the university staff learnt through a TT conversation with person M. (in her 70s) about the game “Hoy”. The university staff member later explained that he had no idea what older people do in day centres and felt that he learnt something new through the conversation and having a view into the day centre. | SS | The older conversant was happy to share about hobbies/activities in her life. University staff learnt what people do in day centres. |

| Day 1 | 3 | Students were hesitant to put their hand into the hole: “I wouldn’t put my hand in there. I’d expect to find a keyboard”. “You need to tell me who it is connected to”. | E D | The hole was not inviting as a mechanism. Expectations by students were to have a keyboard for typing rather than speaking. The ambiguity of the kiosk and mechanism created a need for information. |

| Day 1 | 4 | Three women from a local community group came to see the Teletalker after reading the announcement in the charity’s newsletter. Their reactions were, “really easy to use”, “really simple”. They liked the idea of visual connection with sound and could see their group connected to the over-50s club or with the library. They describe themselves as “still fit”, in comparison to the clientele that has to go to the day centre. | E D SS | The kiosk, mechanism, and concept were perceived as “easy to use” by active older people. Aspirations to connect their group to places of social and public activity. Distinguishing attitude by active older people towards day centre clients. |

| Day 1 | 5 | At the day centre, person A. (in her 80s, female) asked me quietly “Why”? In her view, students and older people did not have the same interests and she would not know what to talk about. She was not interested in trying the TT. | SS | The concept of connecting (and speaking to) students was not attractive to all day centre clients. Not enough commonality or reason to interact with each other. |

| Day 1 | 6 | Three daycentre clients tried out the TT and held small talk with members of the researching team. I had to help with placing their hands over the hole for the sensor to work. | SS E | (Some) interest in exchanging/trying out the TT by day centre clients. Mechanism to switch the sound on and to keep it on was not intuitive. |

| Day 2 | 7 | On Wednesdays, a different group of clients came to the day centre. A woman of this group complained that she had not been informed about the research (as she was on holiday) and that she was not interested in being involved. Although I tried explaining to her what the research was about and that she did not have to be using the TT or even be near it, she did not warm to the idea. She did not accept compromises such as moving the Teletalker to a different point in the room where she would not been seen. Her objection to the TT created negativity and suspicion from other day centre clients towards the TT, which meant that I decided to keep the TT switched off at the day centre for the day. | SS | The day centre client, who felt not well informed enough about the research took an opposing position and was not prepared to make compromises. The dynamics in the day centre changed because this woman was opinion-leading. Her peers followed her suspicious attitude towards the research. In conversation with the day centre management team, I learnt how clients have their preferences in seats and activities. The management team had observed opinion leaders around the tables who strongly influence the dynamics towards activities. |

| I installed myself with a laptop in the university building and connected to the TT (university kiosk). | ||||

| Day 2 | 8 | Some people waved, but no one came to talk to me through the TT. | SS | The view attracted some interest, but people were hesitant to try out the TT. |

| Day 2 | 9 | One student said after trying the TT, “Not very hygienic to put your hand in there”. She wanted a movable camera and to update the style of the kiosk, stating, “It doesn’t look modern”. She would have liked to have the TT like a help desk service in an office. | E D | The hole mechanism deterred people from using it. Form and style of the kiosk not attractive enough for this student. Movable camera as added functionality to improve the view. Aspirations to use it as a help desk. |

| Day 2 | 10 | One of the students suggested giving the TT the look of a jukebox, as this would be something to connect young and old. Another student suggested having a switch to change locations for the view. | D E | “Jukebox” design as a connecting point for young and old. Switching the view into different locations as added functionality to make the TT proposition more attractive. |

| Day 3 | 11 | Reaction by a member who works with vulnerable older people was initial disappointment, “It is chunky, in the open and what’s the difference to Skype?”. He expected the TT to connect, by a “hand push”, children to their grandparents in a care home. A person of the day centre management team defended the TT, “It’s a very good way of introducing older people to technology and it’s not about people staying at home.” | D E SS | The form and functionality disappointed this particular person (who had increased expectations because we had several conversations beforehand). He expected a simple video telephone with one button to speak and to be used in a quiet place. Day centre management understood that demonstrating the TT in the day centre is about bringing technology to places where older and mostly computer illiterate people meet. |

| Day 3 | 12 | A student looked all the way around the TT to see how it worked and he was impressed by the hand mechanism. | E D | The bespoke volume mechanism made a student curious. |

| Day 3 | 13 | Another student in favour of the TT suggested to connect different countries (e.g., India with the U.K.). | D | Aspirations to have a connection or view into a different country (similar suggestion to return 10). |

| Day 3 | 14 | Member of university staff conversed with three daycentre clients through the TT. One of the day centre clients used it for the second time and became comfortable with the hand mechanism. | SS E | Interest in interacting with people and trying out the technology was generated and maintained by having an interesting conversation partner (member of university staff). One older person learnt how to use the hand mechanism. |

| Day 3 | 15 | Two young students went straight to the TT at university. One said, “It’s here where you can watch old people and speak to the old dudes.” The other answered, “how cute”. | SS | (Patronising) attitude by young people towards older people. The TT was an exciting event for them. |

| Day 3 | 16 | Two more women from the local club (see return no. 4) came to see the TT, but problems with the sound quality made it impossible for them to experience a conversation through the TT. They searched around the TT to see how the connection worked. | D E | The TT was curiosity evoking, despite the sound not working. A functional prototype with good sound quality was crucial to generate an enjoyable experience. |

| Day 4 | 17 | The TT was moved into the hallway of the Age U.K. day centre, near the reception desk. Some Friday day clients were part of the Wednesday group, who previously rejected the TT (return 7). I could hear that they were pleased that they were not overheard playing bingo and that the “ghastly thing”, the “big brother” thing, was removed from the main hall. | SS D | Negative attitudes towards the TT with regards to being seen and heard were expressed. |

| Day 4 | 18 | Q. (in his 70s), a volunteer for the day centre reception desk (not computer literate), was sceptical of the TT. He did not really want to have the “thing” near him. I played “kleine Nachtmusik” on YouTube and demonstrated how the hand mechanism worked. This changed his attitude. He enjoyed being in control of switching the music on and off by simply placing his hand over the little hole, or, as I showed him, by placing a piece of paper there to black out the light. He was a big fan of Mozart and used to play music himself. | SS E | Initial negative attitude towards the TT was changed by finding something that interested Q., i.e., classical music. The hand mechanism was attractive once Q. understood it. The idea to use a piece of paper made the mechanism act like a switch. |

| Day 4 | 19 | Q. spoke through the TT with a younger member of the researching team. | SS | Q. was pro-active and opened up to cross-generational conversations. |