The Third Transitional Identity of Migrant Adolescents. The Case of Hotel House, an Italian Multi-Ethnic Skyscraper-Ghetto

Abstract

:1. Introduction

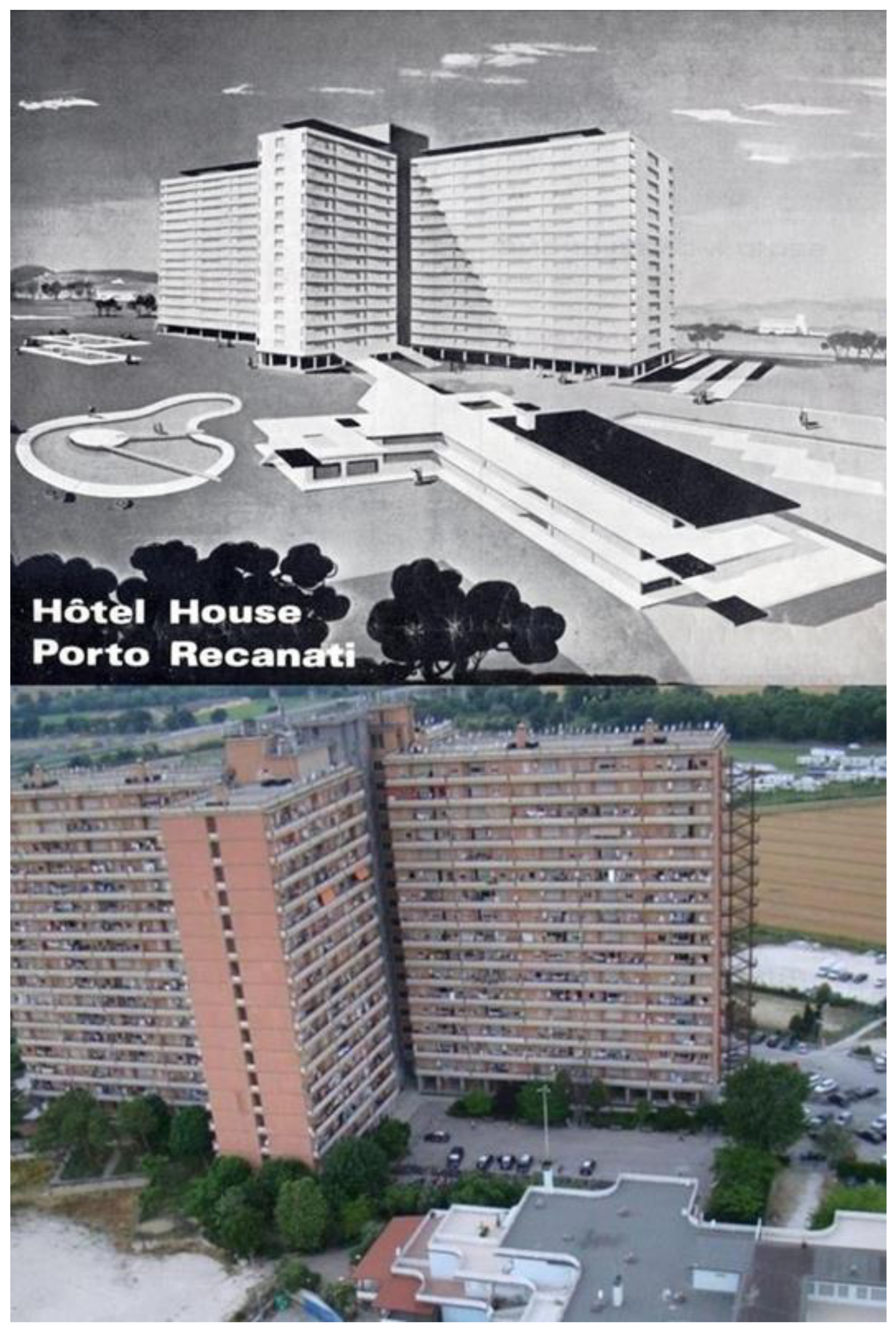

Hotel House is the most fascinating and perplexing building in Italy: a semi-derelict tower block that has become synonymous, in the Italian imagination, with drug dealing, prostitution and clandestine migrants. Nobody knows how many people live here. In the summer, when large numbers of Bangladeshi and Senegalese people come to the area to work as beach vendors, the number probably surpasses 3000.

1.1. The Context for Hotel House

High-concept architectural projects that have, over time, become dystopian citadels for drug dealers and an Italian and immigrant underclass. These are places where honest destitution mixes with criminal wealth, and where the Italian state often appears to have lost control completely. Today it’s almost inconceivable that a local would buy a flat here, but there’s still a regular turnover of immigrants attracted by the dirt-cheap property and the presence of so many compatriots. It’s a place of strange speculation: when things are this cheap, both the poor and those who exploit them see an opportunity (flat now costs only €6000). For as long as everything is in private hands, the state is unwilling or unable to intervene [5].

1.2. Identity Formation in 1.5 Generation Migrants

2. Aims of the Study

- measures the levels of self-concept clarity, perception of self-determination, ethnic group identification in Hotel House, relationships with mother and father and depression or satisfaction with one’s life;

- evaluates the impact of self-concept clarity, self-determination, ethnic group identification and relationship with the parents on the depressive symptoms or satisfaction with life.

- A lack of self-concept clarity, lower life satisfaction or self-determination, difficult relationships with parents or with ethnic group, disorder symptoms especially with growth and mostly girls compared to boys;

- Self-concept clarity, self-determination, identification with ethnic group and attachment with parents as protective factors against depression, which in turn increases life satisfaction.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

3.2. Procedure

3.3. Measures

- Self-Concept Clarity Scale (SCC) [25]: It consists of 12 items, scored on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A sample item is as follows: ‘In general, I have a clear sense of who I am and what I am’. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.73.

- Self-Determination Assessment Scale [26]: It consists of 14 items, scored on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (someone else makes decisions on my behalf) to 5 (it is always me who makes decisions). A sample item is as follows: ‘I make my own decisions’ Cronbach’s alpha was 0.77.

- Short version of the Identification Scale [27]: This scale was used to assess the positive identification processes in the group. It consists of six items with a response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A sample item is as follows: ‘The success of my ethnic group in Hotel House is also my success’. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.77.

- Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA) [28]: It is a self-reporting tool aimed at measuring the quality of the relationships between adolescents and their fathers (12 items) and mothers (12 items). A six-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (completely untrue) to 6 (completely true), was used. The singled-out factors measured three dimensions in the relationship between adolescents and their parents: trust, communication and alienation, recoded as closeness. Some sample items are as follows: ‘My father/mother respects my feelings’ (trust); ‘I talk to my father/mother about my problems and worries’ (communication); ‘My father/mother does not care much about me (Reverse)’ (closeness). The reliability of the factors, based on value of Cronbach’s alpha, was adequate: trust on father and mother = 0.79; communication with father = 0.76; communication with mother = 0.78; closeness with father = 0.71; closeness with mother = 0.71.

- The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) [29]: This tool was used to assess depressive symptoms. The CDI is a self-report questionnaire aimed at screening subclinical depressive symptoms among children and adolescents. The CDI consists of 27 items, scored on a three-point scale: 1 (false), 2 (a bit true) and 3 (very true). A sample item is as follows: ‘I am sad all the time’. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91.

- The Satisfaction with Life Scale [30]: It is a short, five-item instrument, with a response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). It measures global cognitive judgments of satisfaction with one’s life. The following is an example: ‘I am satisfied with my life.’ Cronbach’s alpha was 0.71.

4. Results

Regression Analysis

5. Discussion and Conclusions

| (1) | |

| 1I: | Adesso cosa pensi, di preciso di questa tua esperienza? |

| What do you specifically think now about this experience of yours? | |

| 2G: | Adesso, non vorrei né lasciare Italia né Bangladesh. |

| Now, I wouldn’t like to leave either Italy or Bangladesh. | |

| 3 | Vorrei stare in mezzo. Stare in tutte due parti. Veramente. |

| I would like to stay in between. Stay in both parts. Really. |

| (2) | |

| 1I | Tu invece D, cosa vorresti fare? |

| What would you like to do, D? | |

| 2D | Io voglio andare in un altro Paese. |

| I want to go to another country. | |

| 3I | Dove? |

| Where? | |

| 4F | In Canada. |

| In Canada. | |

| 5D | No in Canada. (In un posto) più bello d’Italia. |

| No in Canada. (In a place) more beautiful than Italy. | |

| 6G | Io pure mi sa che me ne vado. |

| I think I’m going away too. | |

| 7I | Cos’è che non ti piace dell’Italia? |

| What don’t you like about Italy? | |

| 8D | Che c’è crisi. |

| That there is a crisis. |

- When self-determination increases, depression decreases;

- Regarding attachment with parents, when the father’s closeness increases, depression decreases and life satisfaction increases. Mother’s closeness is only negatively associated with depression.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Additional Notes

References

- Huang, C.Y.; Cheah, C.S.; Lamb, M.E.; Zhou, N. Associations between parenting styles and perceived child effortful control within Chinese families in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Taiwan. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2017, 48, 795–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schwartz, S.J.; Meca, A.; Cano, M.Á.; Lorenzo-Blanco, E.I.; Unger, J.B. Identity Development in Immigrant Youth. Eur. Psychol. 2018, 23, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phalet, K.; Fleischmann, F.; Hillekens, J. Religious Identity and Acculturation of Immigrant Minority Youth toward a Contextual and Developmental Approach. Eur. Psychol. 2018, 23, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, L. Il Ghetto. Il Funzionamento Sociale e Psicologico Della Segregazione; Res Gestae: Milano, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T. An Unsolved at Italys Most Notorious Towerblock. 31 July 2018. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/jul/31/an-unsolved-at-italys-most-notorious-tower-block (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Meca, A.; Sabet, R.F.; Farrelly, C.M.; Benitez, C.G.; Schwartz, S.J.; Gonzales-Backen, M.; Picariello, S. Personal and cultural identity development in recently immigrated Hispanic adolescents: Links with psychosocial functioning. Cult. Divers. Ethnic. Minor. Psychol. 2017, 23, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, C.; Burns, T.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Pinfold, V.; Priebe, S. Social exclusion and mental health. Conceptual and methodological review. Br. J. Psychiatry 2007, 191, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regione Marche. I Numeri ISTAT Sull’immigrazione. 2019. Available online: https://www.regione.marche.it/News-ed-Eventi/Post/51993/I-numeri-Istat-sull-immigrazione-2019 (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Cancellieri, A. Hotel House; Professionals Dreamers: Trento, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Viminale. 10 March 2019. Available online: http://www.interno.gov.it (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- Crocetti, E.; Schwartz, S.J.; Fermani, A.; Meeus, W. The Utrecht Management of Identity Commitments Scale (U-MICS): Italian Validation and Cross-National Comparisons. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 26, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.J.; Vignoles, V.L.; Brown, R.; Zagefka, H. The identity dynamics of acculturation and multiculturalism: Situating acculturation in context. In Handbook of Multicultural Identity; Benet-Martínez, V., Hong, Y.Y., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosic, A.; Mannetti, M.; Sam, D.L. The role of majority attitudes towards out-group in the perception of the acculturation strategies of immigrants. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2005, 29, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatier, C. Ethnic and national identity among second-generation immigrant adolescents in France: The role of social context and family. J. Adolesc. 2008, 31, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, E.W. Cultural Values and Coparenting Quality in Families of Mexican Origin. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2018, 49, 1523–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, L.; Rania, N.; Tassara, T.; Cardinali, P. Family routine behaviours and meaningful rituals: A comparison between Italian and migrant couples. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2016, 44, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermani, A.; Muzi, M.; Crocetti, E.; Meeus, W. I genitori sono importanti per la chiarezza del concetto di Sé? Studenti e lavoratori a confronto: Psicol. Clin. e dello Svilupp. 2016, 1, 55–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut, R.G. Assimilation and its discontents: Between rhetoric and reality. Int. Migr. Rev. 1997, 31, 923–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alcántara, C.; Estevez, C.D.; Alegría, M. Latino and Asian Immigrant Adult Health: Paradoxes and Explanations. In Oxford Handbook of Acculturation and Health; Schwartz, S.J., Unger, J.B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakash, O.; Nagar, M.; Shoshani, A.; Zubida, H.; Harper, R.A. The effect of acculturation and discrimination on mental health symptoms and risk behaviors among adolescent migrants in Israel. Cultur. Divers. Ethnic. Minor. Psychol. 2012, 18, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J. The social identity theory of ingroup behaviour. In Psychology of Ingroup Relations; Worchel, S., Austin, W., Eds.; Nelson Hall: Chicago, IL, USA, 1986; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales-Backen, M.A.; Bámaca-Colbert, M.Y.; Allen, K. Ethnic identity trajectories among Mexican-origin girls during early and middle adolescence: Predicting future psychosocial adjustment. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 52, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocetti, E.; Schwartz, S.J.; Fermani, A.; Klimstra, T.; Meeus, W. A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Identity Statuses between Two European Countries. Eur. Psychol. 2012, 17, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crocetti, E.; Fermani, A.; Pojaghi, B.; Meeus, W. Identity Formation in Adolescents from Italian, Mixed, and Migrant Families. Child. Youth Care Forum 2011, 40, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.D.; Trapnell, P.D.; Heine, S.; Katz, I.M.; Lavalle, L.F.; Lehman, D.R. Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates and cultural boundaries. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soresi, S.; Nota, L.; Ferrari, L. Autodeterminazione e scelte scolastico-professionali: Uno strumento per l’assessment. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia dell’Orientamento 2004, 5, 26–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner, G.E.; Ashforth, B.E. Evidence toward an expanded model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armsden, G.C.; Greenberg, M.T. The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 1987, 16, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, M. The Children’s Depression Inventory. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1985, 21, 995–998. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fermani, A.; Crocetti, E.; Meeus, W. Attaccamento ai genitori e disagio emotivo in adolescenti appartenenti a famiglie italiane, miste e migranti: Un approccio multi-metodo. Studi Familiari 2010, 2, 22–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cicei, C.C. Examining the association between self-concept clarity and self-esteem on a sample of Romanian students. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 4345–4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crocetti, E.; Van Dijk, M.P. Self-Concept Clarity. In Encyclopedia of Adolescence; Levesque, R., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanier, M.L.; Mattucci, N.; Santoni, C. Luoghi di Inclusione, Luoghi di Esclusione. Realtà e Prospettive dell’Hotel House di Porto Recanati; EUM: Macerata, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bongelli, R.; Riccioni, I.; Vincze, L.; Zuczkowski, A. Questions and epistemic stance: Some examples from Italian conversations. Ampersand 2018, 5, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemiec, C.P.; Lynch, M.F.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Bernstein, J.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The antecedents and consequences of autonomous self-regulation for college: A self-determination theory perspective on socialization. J. Adolesc. 2006, 29, 761–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Promoting self-determined school engagement: Motivation, learning, and well-being. In Educational Psychology Handbook Series. Handbook of Motivation at School; Wenzel, K.R., Wigfield, A., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2009; pp. 171–195. [Google Scholar]

- Dion, K.K.; Dion, K.L. Gender and cultural adaptation in immigrant families. J. Soc. Issues 2001, 3, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villano, B.; Zani, B. Processi psicosociali nelle esperienze di migrazione. In Prospettive di Psicologia Culturale; Mazzara, B.M., Ed.; Carocci: Roma, Italy, 2007; pp. 177–195. [Google Scholar]

- Gozzoli, C.; Regalia, C. Migrazioni e Famiglie. Percorsi, Legami e Interventi Psicosociali; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Poggioli, D. Minori Migranti Che Raggiungono I Familiari Dopo la Separazione e Suicidio: Fattori di Rischio e di Protezione. 16 March 2019. Available online: http://www.prevenzionesuicidio.it/fattoririschio2.html (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- Atti Parlamentari. 10 March 2019. Available online: http://www.camera.it/_dati/leg17/lavori/documentiparlamentari/indiceetesti/022bis/019/00000009.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- Cicognani, E. Psicologia Sociale e Ricerca Qualitativa; Carocci: Roma, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zucchermaglio, C.; Alby, F.; Fatigante, M.; Saglietti, M. Fare Ricerca Situata in Psicologia Sociale; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fermani, A.; Cavagnaro, E.; Staffieri, S.; Carrieri, A.; Stara, F. Can psychological wellbeing be a predictor of change through travel? An exploratory study on young Dutch travellers. Tourismos 2017, 12, 72–103. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | All municipality data referring to 2018 were collected by one of the authors of this paper, who personally checked the municipal registers. |

| 2 | The source for all the descriptions about history and the architectural features of the Hotel House was Cancellieri [9]. |

| 3 | In this article we limit ourselves to presenting only two exemplary excerpts because the qualitative analysis of the whole corpus of in-depth interviews is still in progress. The letters I and G in extract (1) stand for the interviewer and the girl’s name respectively; similarly, the letters D, F, G in extract (2) stand for the names of the participants, which have been removed to ensure their anonymity. |

| 4 | See also [35]. |

| Citizenship | Males n (%) | Females n (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Senegalese | 308 (18.3%) | 75 (4.5%) | 383 (22.8%) |

| Pakistani | 262 (15.6%) | 66 (3.9%) | 328 (19.5%) |

| Bangladeshi | 199 (11.8%) | 114 (6.8%) | 313 (18.6%) |

| Nigerian | 52 (3.1%) | 25 (1.5%) | 77 (4.6%) |

| Moroccan | 28 (1.7%) | 26 (1.5%) | 54 (3.2%) |

| Afghan | 36 (2.1%) | 0 | 36 (2.1%) |

| Macedonian | 17 (1.0%) | 10 (0.6%) | 27 (1.6%) |

| Indian | 16 (1.0%) | 4 (0.2%) | 20 (1.2%) |

| Italian | 156 (9.3%) | 105 (6.2%) | 261 (15.5%) |

| Tunisian | 72 (4.3%) | 50 (3.0%) | 122 (7.3%) |

| Algerian | 13 (0.8%) | 6 (0.4%) | 19 (1.1%) |

| Chinese | 8 (0.5%) | 6 (0.4%) | 14 (0.8%) |

| Egyptian | 4 (0.2%) | 2 (0.1%) | 6 (0.4%) |

| Romanian | 2 (0.1%) | 3 (0.2%) | 5 (0.3%) |

| Dominican | 1 (0.1%) | 4 (0.2%) | 5 (0.3%) |

| Argentinian | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 2 (0.1%) |

| Bosnian | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Brazilian | 1 (0.1%) | 0 | 1 (0.1%) |

| French | 0 | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Ghanaian | 1 (0.1%) | 0 | 1 (0.1%) |

| Eritrean | 0 | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Maliana | 1 (0.1%) | 0 | 1 (0.1%) |

| Moldovan | 1 (0.1%) | 0 | 1 (0.1%) |

| Ukrainian | 0 | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Hungarian | 0 | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| 11–14 Early Adolescents n = 54 | 15–19 Middle Adolescents n = 37 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males n = 32 M (SD) | Females n = 22 M (SD) | Males n = 27 M (SD) | Females n = 10 M (SD) | |

| Self-concept clarity | 2.55 (0.60) a | 2.78 (0.73) a | 2.60 (0.63) a | 2.56 (0.75) a |

| Self-determination | 2.86 (0.75) a | 2.24 (0.86) a,b | 2.88 (1.21) a | 1.12 (0.76) b |

| Group identification | 3.44 (0.94) a | 3.65 (0.55) a | 3.41 (0.83) a | 3.57 (1.19) a |

| Father attachment | ||||

| Trust | 4.97 a (0.72) | 4.82 a (1.11) | 4.26 a (1.46) | 4.2 a (1.58) |

| Communication | 4.27 a (1.14) | 4.00 a (0.93) | 3.89 a (1.39) | 3.87 a (0.86) |

| Closeness | 4.73 b (1.14) | 4.40 b (0.92) | 4.42 b (1.33) | 3.30 a (1.42) |

| Mother attachment | ||||

| Trust | 5.08 a (1.09) | 4.88 a (1.22) | 4.95 a (1.06) | 4.60 a (1.57) |

| Communication | 4.47 a (1.16) | 4.32 a (1.26) | 4.24 a (1.18) | 4.47 a (0.82) |

| Closeness | 5.02 a (1.03) | 4.82 a (1.20) | 4.78 a (1.26) | 4.02 a (1.25) |

| Depression | 1.23 (0.23) a | 1. 45 (0.26) a | 1.33 (0.31) a | 1.90 (0.22) b |

| Satisfaction | 3.81 (0.56) b | 3.72 (0.56) a,b | 3.66 (0.44) a,b | 3.28 (0.53) a |

| Total n = 91 | Depression | Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|

| Self-concept clarity | 0.01 (0.19) | −0.05 (−0.05) |

| Self-determination | −0.20 * (0.20) | 0.14 * (0.14) |

| Identification | 0.13 (0.09) | 0.02 (0.06) |

| Father attachment | ||

| Trust | −0.07 (−0.17) | 0.17 (0.22) |

| Communication | 0.07 (0.01) | −0.16 (0.04) |

| Closeness | −0.28 * (−0.38 ***) | 0.28 * (0.26 **) |

| Mother attachment | ||

| Trust | −0.09 (−0.07) | 0.03 (0.11) |

| Communication | 0.07 (0.08) | 0.06 (0.03) |

| Closeness | −0.19 * (−0.37 ***) | 0.05 (0.22 *) |

| R2 | 0.26 *** | 0.16 * |

| Depression | Life Satisfaction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff B | Sig. | Exp(B) | Coeff B | Sig. | Exp(B) | |

| Gender (ref females) | ||||||

| Males | −2.017 | 0.000 *** | 0.133 | 0.687 | 0.137 | 1.987 |

| Constant | 1.273 | 0.003 ** | 3.571 | −0.788 | 0.039 * | 0.455 |

| Case numbers | 91 | 91 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fermani, A.; Riccioni, I.; Vincze, L.; Cingolani, G.; Bongelli, R. The Third Transitional Identity of Migrant Adolescents. The Case of Hotel House, an Italian Multi-Ethnic Skyscraper-Ghetto. Societies 2021, 11, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11020051

Fermani A, Riccioni I, Vincze L, Cingolani G, Bongelli R. The Third Transitional Identity of Migrant Adolescents. The Case of Hotel House, an Italian Multi-Ethnic Skyscraper-Ghetto. Societies. 2021; 11(2):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11020051

Chicago/Turabian StyleFermani, Alessandra, Ilaria Riccioni, Laura Vincze, Giorgio Cingolani, and Ramona Bongelli. 2021. "The Third Transitional Identity of Migrant Adolescents. The Case of Hotel House, an Italian Multi-Ethnic Skyscraper-Ghetto" Societies 11, no. 2: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11020051

APA StyleFermani, A., Riccioni, I., Vincze, L., Cingolani, G., & Bongelli, R. (2021). The Third Transitional Identity of Migrant Adolescents. The Case of Hotel House, an Italian Multi-Ethnic Skyscraper-Ghetto. Societies, 11(2), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11020051