Surf Tourism in Uncertain Times: Resident Perspectives on the Sustainability Implications of COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study Backround

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surfers as Environmental Stewards

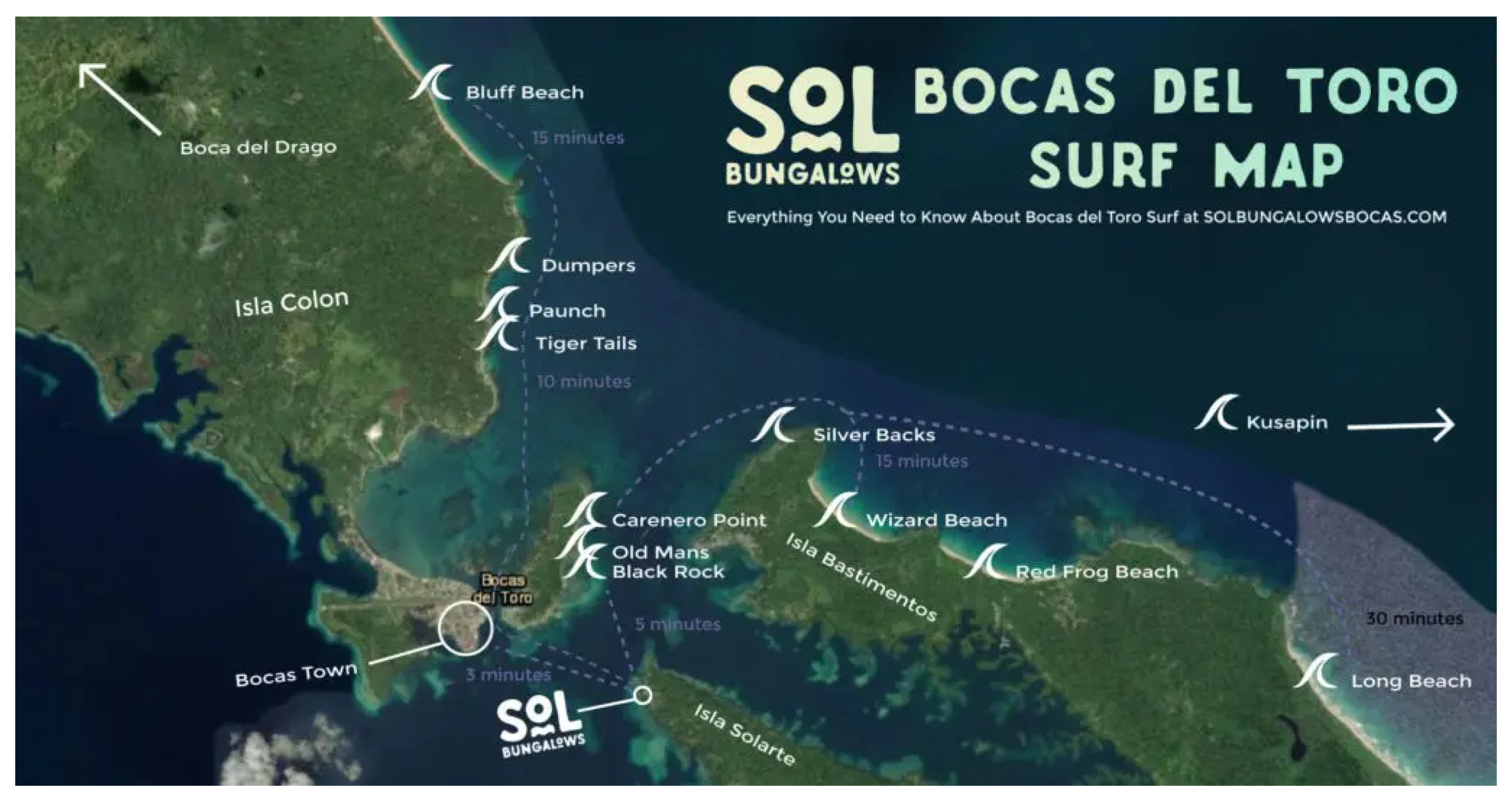

In the late 2000s, there was hardly anyone here surfing, which was incredible. We kept finding good waves and looking further for more on boats and stuff…. The wave we call Dumpers now is because all the trash in town was collected and just dumped at the end of the road there on the beach—it wasn’t buried or anything. Some of us still surfed it by boat, but it was gross honestly. Surfers eventually got together and convinced the government to clean that up and promised it would be good for not only surf tourism but all tourism. It is actually kind of funny that visiting surfers think it’s called Dumpers because the wave is dumpy or heavy. They have no clue that there was literally medical waste on the beach where they are surfing.

We just got plastic bags and straws banned and we were beginning to see benefits, but now there are masks turning up on the side of the road and in the water. It’s not terrible here, but you still hate to see it and it bums you out. We surf to forget about the pandemic for a bit each day and that kind of trash has a way of reminding you.

Only surfers have installed proper boat moorings that keep anyone from dropping anchor or doing any damage to reefs. The moorings in the protected area are impractical and no one uses them and key snorkel reefs are a free for all, but surfers got that part right. We are aren’t great at a lot of things, but are pretty good at protecting our breaks.

Lots of development is happening on land around Paunch and there really isn’t anything we can do about it, but once they started drilling into the reef, an environmental protest erupted. We committed to stopping the encroachment into the water by any means possible.

3.2. Overcrowding, Overdevelopment and Sacrifice Zones

I hate to sound sensible, but if foreigners hadn’t moved here and started businesses and bars and promoted tourism etc., none of this damaging development on the coast would have happened and the waves would not be so crowded. We have to share the blame… Sucks, but I’m a part of the problem as well so I’m not pointing fingers.

I don’t think people understand how delicate surf-breaks are. People just keep building and building around them like it will have no impact. I thought it was illegal to build on the ocean side of the road, period. But now there is a trendy restaurant-bar and a house right there on the beach and people are clearing more land. And the pandemic just seems to have accelerated land purchases and construction, rather than slowed it. Things that have been sitting for sale for years are getting gobbled up right now.

Most of the surf boat drivers know the deal, you take the tourists to Paunch or Crowdenero (actually called Carenero). They aren’t secrets anymore. We just have to deal with them being crowded. It sucks because these are the only two consistent waves that we have—people might say otherwise, but it is just not true. It looks on paper like there are all these waves here and most of the waves getting all the press rarely break. So, people come here thinking they are going to surf this barrel or that wave they see in surf videos or Instagram, but in reality, they are going to surf Paunch and Carenero mostly, with the rest of us.

3.3. Community Tensions and the Possible Emergence of a New Surf Ethic

I understand people need to make a living, but making a living off of surfing requires you to pimp out the sport and the place where you live. I get why people do it, you surf, you want make money doing it, blah blah. But they are actively ruining what we have here and then they look around like they don’t know what’s going on. Particularly during the pandemic with surf businesses advertising that its uncrowded and safe and offering deals to visit. It exposes what they have been doing for years as selfish and damaging to the image of the place. If the crowds keep getting worse and more development comes, I am getting out of here.

This guy has 20 k followers and is blasting the interwebs with photos of how good and empty the waves are. He’s calling it COVIDtopia—guaranteeing waves when the reports look good and offering two-for-one deals. Then they come and he wants to drop 10 surfers off at the break at one time. They ran this guy out of Carenero so he keeps coming to Paunch. I am shocked some of the more senior locals haven’t ran him out of here yet as well, but I think it’s because something about the pandemic has caused the tourists to be super polite and respectful. They seem to acknowledge that dropping 10 guys off is shitty and they don’t paddle-battle or act entitled, but its bad form by the business owner. As long has he gets his, that’s all that matters to guys like that.

Surfers are selfish. I hate to admit, but when I first heard they were shutting down Panama, my first thought was, at least we will be able to surf without tourists for once. Little did I know, they would be patrolling with police boats making sure we didn’t surf and then people found ways to convince tourists to come as soon as they were able. And locals would surf ten-hours per day. In short, the silver lining was a nice thought, but not a reality. The surf was a crowded as ever.

We kind of all know surfing is growing here and that’s the way it is. Every winter is busier than the one before. But it was quietly understood that you don’t talk about the small summer window that we get here. It’s always kinda been the time for locals who keep around when everyone else leaves. Surf businesses are getting desperate and using the vulnerable time to break the code. And I think people are accepting of it because we feel bad that tourism has been battered during the Pandemic.

The tourists coming in talk about how terrible the pandemic has been where they live and are just so happy to be in a beautiful place surfing and enjoying life. It’s cool to hear them say this and that they don’t want any problems just want to show respect and have a good time. COVID-19 has been bad here too in many ways, but the respect people are showing gives me hope that surfers are seeing things differently. Maybe people will start showing the respect they expect at their home-breaks.

Right now, there are really no other tourists here than surfers which isn’t surprising because all the restrictions needed to come in and there is a curfew, and nothing is open. But seeing surfers navigate it all to get here for our waves helps to remind us that tourism will come back one day and with it, some sense of normalcy. I’m actually glad they are here, which I have never said before. The problem seems to be us locals have too much time and are surfing too much. You know, people who usually work a lot and surf when they can, are just camped out at the beach surfing three times a day. That seems to be causing more crowding than the visitors, but the vibe is good. I think the pandemic has helped everyone realize that surfing is essential to us, but there are bigger things to worry about than fighting over waves.

Yes, visiting surfers have been respectful. They stay away from people, wear masks, and don’t party like they used to. I don’t think anyone has much negative to say about them. Less people are talking about the reality though. They are only visiting high-end all-inclusive surf resorts or staying in foreign owned apartments and just going to the grocery store. Basically, the waves stay crowded, but hardly anyone benefits. Bocas is already basically a big grocery story. I don’t see that changing with how tourism looks today.

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mach, L.; Ponting, J. Establishing a pre-COVID-19 baseline for surf tourism: Trip expenditure and attitudes, behaviors and willingness to pay for sustainability. Ann. Tour. Res. Impirical Insights 2021, 2, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestanza-Ramón, C.; Jiménez-Caballero, J. Nature tourism on the Columbian-Ecuadorian Amazonian border: History, current situation and challenges. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebli, A.; Volgger, M.; Taplin, R. A two-dimensional approach to travel motivation in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, S. Adventure travel and tourism after COVID-19—Business. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 646–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reineman, D.; Koenig, K.; Strong-Cvetich, N.; Kittinger, J. Conservation opportunities arise from the co-occurrence of surfing and key biodiversity areas. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Fluker, M. Behavioural market segments among surf tourists: Investigating past destination choice. J. Sport Tour. 2003, 8, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, C. Polluted leisure and blue spaces: More-than-human concerns in Fukushima. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2019, 45, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robinson, L.; Jarvie, J. Post-disaster community tourism recovery: The tsunami and Arugam Bay, Sri Lanka. Disasters 2008, 32, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurtner, Y. After the Bali bombing—The long raod to recoverty. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2004, 19, 56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Old, J. Transnational surfistas: Surf transnationalism in Nicaragua’s Emerald Coast. In Proceedings of the 6th Biennial Global Wave Conference, Gold Coast, Australia, 10–14 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Laderman, S. Empire in Waves: A Political History of Surfing; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wavelength. Surfing in the time of Ebola. Wavelenght Magazine. 18 July 2016. Available online: https://wavelengthmag.com/surfing-in-the-time-of-ebola/ (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Buckley, R. Surf tourism and sustainable development in Indo Pacific Island—Recreational capacity management and case study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2002, 10, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sotomayor, S.; Barbieri, C. An exploratory examination of serious surfers: Implications for the surf tourism industry. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, L.; Monterrubio, C.; Osorio, M. Social representations of surf tourism’s impacts in Mexico. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2021, 11, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towner, N.; Milne, S. Sustainable surfing tourism development in the Mentawai islands, Indonesia: Local stakeholder perspectives. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2017, 14, 503–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, D.; Ponting, J. Sustainable surf tourism: A community centered approach in Papua New Guinea. J. Sport Manag. 2013, 27, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.; Jiang, Y. A review of research on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.; Park, J.; Li, S.; Song, H. Social costs of tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifpour, M.; Walters, G.; Ritchie, B. Risk perception, prior knowledge, and willingness to travel: Investigating the Australian tourist market’s risk perceptions towards the Middle East. J. Vacat. Mark. 2014, 20, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, B.; Al-Ansi, A.; Lee, M.; Han, H. Impact of health risk perception on avoidance of international travel in the wake of a pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 985–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cañizares, S.; Cabeza-Ramírez, J.; Muñoz-Fernández, G.; Fuentes-García, F. Impact of the perceived risk from Covid-19 on intention to travel. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 970–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajibaba, H.; Gretzel, U.; Leisch, F.; Dolnicar, S. Crisis-resistant tourists. Ann. Tour. 2015, 53, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Senbeto, D.; Hon, A. The impacts of social and economic crises on tourist behaviour and expenditure: An evolutionary approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, M. Risk and uncertainty in travel decision-making: Tourist and destination perspective. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowforth, M.; Munt, I. Tourism and Sustainability: Development and New Tourism in the Third World, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, I.; Maity, P. COVID-19 outbreak: Migration, effects on society, global environment and prevention. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, Y.; Karkour, S.; Ichisugi, Y.; Itsubo, N. Evaluation of the economic, environmental, and social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Japanese tourism industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. World Tourism Barometer and Statistical Annex. 2021. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/epdf/10.18111/wtobarometereng.2021.19.1.1 (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Lenzen, M.; Sun, Y.; Faturay, F.; Ting, Y.; Geschke, A.; Malik, A. The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szromek, A.; Kruczek, Z.; Walas, B. Stakeholders’ attitudes towards tools forsustainable tourism in historical cities. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittichainuwat, B.; Chakraborty, G. Perceived travel risks regarding terrorism and disease: The case of Thailand. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, C.G. From Temporary Migrants to Permanent Attractions: Tourism, Cultural Heritage, and Afro-Antillean Identites in Panama, Tuscaloosa; University of Alabama Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Runk, J. Indigenous land and environmental conflicts in Panama: Neoliberal multiculturalism, changing legislation, and human rights. J. Lat. Am. Geogr. 2012, 11, 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, A. Lifestyle migration to Bocas del Toro Panama: Exploring migration strategies and introducing local implications of the search for paradise. Int. Rev. Soc. Res. 2013, 3, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spalding, A.K. Towards a political ecology of lifestyle migration: Local perspectives on socio-ecological change in Bocas del Toro, Panama. R. Geogr. Soc. 2020, 52, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longboard, R. Surf Scene: The Pioneers of Bocas. The Bocas Breeze, 1 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Suman, D.; Spalding, K. Coastal Resources of Bocas del Toro, Panama: Tourism and Development Pressures and the Quest for Sustainability; University of Miami: Coral Gables, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, C. Surf deja a Costa Rica más de 400 mil millones al año. La Prensa Libre, 5 January 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, A. Help Save on of the Caribbean’s Best Waves. Surfer Magazine, 9 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fadda, N. Entrepreneurial behaviours and managerial approach of lifestyle entrepreneurs in surf tourism: An exploratory study. J. Sport Tour. 2020, 24, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.; Bicudo, P. Surfing tourism plan: Madeira Island case study. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 16, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hritz, N.; Franzidis, A. Exploring the economic significance of the surf tourism market by experience level. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 7, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, L. Surf tourism destination governance in Bocas del Toro, Panama: Understanding how actors in the surf tourism system shape destination development. In Proceedings of the Conference presentation at the National Environment and Recreation Research Symposium, Annapolis, MD, USA, 7–9 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 4th ed.; AltaMira Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 387–412. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, G.R. Methodologies and methods. In Handbook of Tourism Studies; Jamal, T., Robinson, M., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 672–692. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, N.; Foemmel, E. Participant observation. In Handbook of Research Methods in Tourism: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches; Dwyer, L., Gill, A., Seetaram, N., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 377–391. [Google Scholar]

- Evers, C. Polluted Leisure. Leis. Sci. 2019, 41, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, T.; Thomas, H. Qualitative Interviewing; Sage: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Junek, O.; Killion, L. Grounded Theory. In Handbook of Research Methods in Tourism: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches; Dwyer, L., Gill, A., Seetaram, N., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 325–338. [Google Scholar]

- Ponting, J. Consuming Nirvana: An Exploration of Surfing Tourist Space. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Technology Sydney, Ultimo, Australian, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, D.; Ponting, J. STOKE Certified: Initiating sustainability certification in surf tourism. In Handbook on Sport, Sustainability, and the Environment; McCullough, B., Kellison, T., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 301–316. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo, M.; Levine, A.; Espejel, I. A transdisciplinary framework proposal for surf break conservation and management: Bahia de Todos Santos World Surfing Reserve. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 168, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, T. Surf travel: The elephant in the room. In Sustianable Stoke: Transitions to Sustainability in the Surfing World; Borne, G., Ponting, J., Eds.; University of Plymouth Press: Plymouth, UK, 2015; pp. 200–213. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, L.; Abbott, J.A. Representation, Identity, and Environmental Action among Florida Surfers. Southeast. Geogr. 2009, 49, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, F.; Pintassilgo, P.; Pinto, P. Environmental Awareness of Surf Tourists: A Case Study in the Algarve. J. Spat. Organ. Dyn. 2015, 3, 102–113. [Google Scholar]

- Krause. Pilgrimage to the Playas: Surf Tourism in Costa Rica. Anthropol. Action 2012, 19, 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mach, L. Surf-for-development: An exploration of program recipient perspectives in Lobitos, Peru. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2019, 43, 438–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarfe, B.E.; Healy, T.R.; Rennie, H.G.; Mead, S.T. Sustainable management of surfing breaks—An overview. Reef J. 2009, 1, 44–73. [Google Scholar]

- Nazer, D. The tragic comedy of the surfers’ commons. Deakin Law Rev. 2004, 9, 655–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Da Rosa, S.; dos Anjos, A.; de Lima Pereira, M.; Junior, M. Image perception of surf tourism destination in Brazil. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 6, 1111–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belyea, C. The Pathfinder Diaries; Lulu Publishing Services: Morrisville, NC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Usher, L.; Gomez, E. Surf localism in Costa Rica: Exploring: Exploring territoriality among Costa Rica and foreign resident surfers. J. Sport Tour. 2016, 20, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, L.; Kerstetter, D. Residents’ perceptions of quality of life in a surf tourism destination: A case study of Las Salinas, Nicaragua. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2014, 14, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towner, N.; Lemarie, J. Localism at New Zealand surfing destinations: Durkheim and the social structure of communities. J. Sport Tour. 2020, 24, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, K. The American Surfer: Radical Culture and Capitalism; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, N.; Brown, D. Surfing and Social Theory: Experience, Embodiment and Narrative of the Dream Glide; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ratten, V. Entrepreneurial intentions of surf tourists. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, L.; Walmsley, A.; Beaumot, E.; Sutton, C. ‘Just want to surf, make boards and party’: How do we identify lifestyle entrepreneurs within the lifestyle sports industry? Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 917–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemelin, H.; Dawson, J.; Stewart, E.; Maher, P.; Lueck, M. Last-chance tourism: The boom, doom, and gloom of visiting vanishing destinations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvani, A.; Lew, A.; Perez, M. COVID-19 is expanding global consciousness and the sustainability of travel and tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, L.; Ponting, J. Governmentality and surf tourism destination governance. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1845–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouso, S.; Borja, A.; Fleming, L.; Gomez-Baggethun, E.; White, M.; Uyarra, M. Contact with blue-green spaces during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown beneficial for mental health. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756, 143984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, M.; Oyekanmi, K.; Gibson, A.; South, E.; Bocarro, J.; Hipp, J. Nature Prescriptions for Health: A Review of Evidence and Research Opportunities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, E.; Kindermann, G.; Domegan, C.; Carlin, C. Blue care: A systematic review of blue space interventions for health and wellbeing. Health Promot. Int. 2018, 35, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nichols, W.J. Blue Mind: The Surprising Science That Shows How Being Near, in on, or under Water Can Make You Happier, Healthier, More Connected, and Better at What You Do; Hachette Book Group: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Caddick, N.; Smith, B.; Pheonix, C. he effects of surfing and the natural environment on the wellbeing of combat veterans. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 35, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Janiri, D.; Carfì, A.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Bernabei, R.; Landi, F.; Sani, G.; COVID GA; Post-Acute Care Study Group. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Patients after Severe COVID-19 Infection. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 567–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, R.C.; Guitart, D.; Shakeela, A. Contested surf tourism resources in the Maldives. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 64, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, L.; Ponting, J. A nested socio-ecological systems approach to understanding the implications of changing surf-reef governance regimes. In Lifestyle Sports and Public Policy; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S.A.; Assenov, I. Developing a surf resource sustainability index as a global model for surf beach conservation and tourism research. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 19, 760–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponting, J.; McDonald, M.; Wearing, S.L. De-constructing wonderland: Surfing tourism in the Mentawai Islands, Indonesia. Soc. Leis. 2005, 28, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scheske, C.; Rodriquez, M.A.; Buttazzoni, J.; Strong-Cvetich, N.; Gelcich, S.; Monteferri, B.; Rodriquez, L. Surfing and marine conservation: Exploring surf-break protection as IUCN protected area categories and other effective area-based conservation measures. Aquatic Conservation: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2019, 29, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mach, L.J. Surf Tourism in Uncertain Times: Resident Perspectives on the Sustainability Implications of COVID-19. Societies 2021, 11, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030075

Mach LJ. Surf Tourism in Uncertain Times: Resident Perspectives on the Sustainability Implications of COVID-19. Societies. 2021; 11(3):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030075

Chicago/Turabian StyleMach, Leon John. 2021. "Surf Tourism in Uncertain Times: Resident Perspectives on the Sustainability Implications of COVID-19" Societies 11, no. 3: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030075

APA StyleMach, L. J. (2021). Surf Tourism in Uncertain Times: Resident Perspectives on the Sustainability Implications of COVID-19. Societies, 11(3), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030075