1. Introduction

The question of academic freedom and the wider issue of freedom of speech and the need to limit speech, indeed, at times, to criminalise it, has developed as an area of interest and concern over the last decade both within educational theory and academia more generally [

1,

2,

3]. Indeed, concerns that universities are becoming institutions prone to limit rather than expand ideas led the UK education secretary, Gavin Williamson, to promote the need for students to be exposed to, rather than protected from, “outlandish, provocative or uncomfortable ideas” [

4]. Indeed, such are the concerns about academic freedom that the British government plans for a ‘free speech champion’ to regulate England’s campuses.

In the past, key concerns about academic freedom related to external pressure from conservative groups, churches and governments or to economic pressure—something that led to the American Association of University Professors writing the 1915 Declaration of Principles, regarding the principles on academic freedom and tenure (see

Appendix A). By contrast, today it appears that most forms of pressure that limit academic freedom come from within the university; from practices and processes developed to support the “student experience” and protect student wellbeing. A recent Civitas report [

5], for example, found that 86 percent of British universities faced either severe or moderate free speech restriction. Key to most of the restrictions were policies, practices and forms of activism within the academy itself.

The Civitas report argues that today most of the measures that limit academic freedom come in the form of, e.g., free speech policies that actually limit speech; from what is described as a form of “cancel culture”; internal incidents of regulations related to particularly sensitive issues like that of “transphobia”; and university policies around bullying and harassment, where “personal offence”, for example, is claimed by a staff member or student. Where there is external pressure on British universities this, it is argued, comes largely in the form of online “activism” and “shaming” via social media, rather than from traditional and conservative institutions.

With regard to the discussion about perceived differences in the approach taken by Russell Group universities and post-1992 universities—where the latter are seen as being potentially more restrictive [

6]—the Civitas report found that there was little difference between these university sectors in terms of levels of restrictions on academic freedom, with Oxbridge universities being among the most restrictive within the UK.

Within sociology, a key reason for the trend towards regulating academic freedom and freedom of speech relates to the cultural and political relegation of freedom as a “first order principle” in comparison to that of safety [

7]. Safety, it is argued, has become a new moral absolute that constantly expands its remit and incorporates the idea of “psychological safety”, where words themselves are understood as a form of “harm”. When it comes to the contestation between freedom and safety, Frank Furedi argues, the “securitisation of freedom” means that “freedom needs to be regulated to minimize attendant risks and harms”.

Within legal theory we find that for over three decades, concerns have been raised about the expanding meaning of harm, something that is understood to have developed most significantly since the late 1980s [

8]. This elevation of harm, Furedi argues, is interconnected with what he calls a “therapeutic culture” [

9,

10]. For Ecclestone, this elevation of harm within a therapeutic culture, and within education, places an emphasis upon “emotional harm” and risks, placing safety ahead of freedom with regard to academic practices [

11].

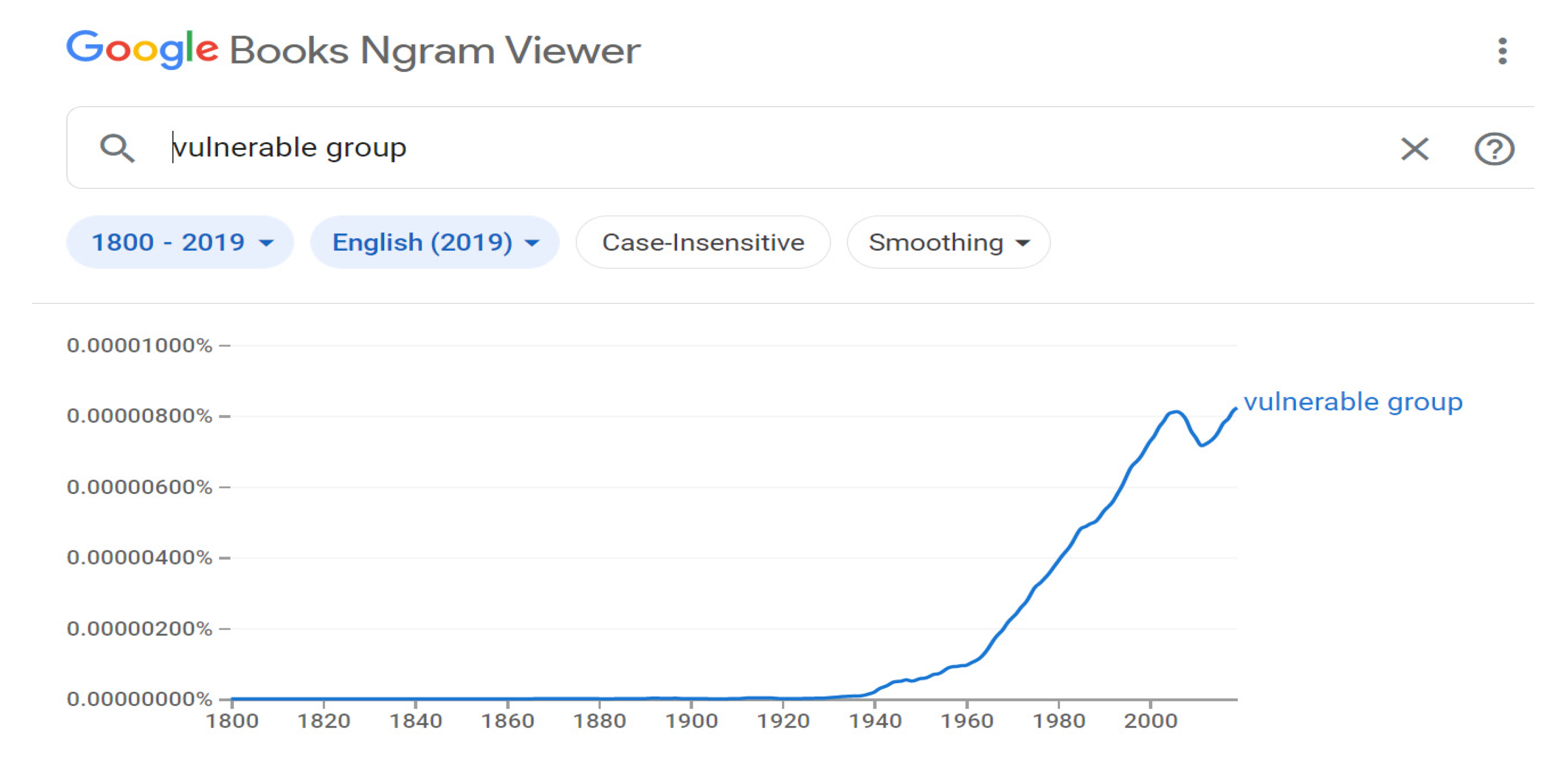

One way to think about this development is to examine the way in which the idea of ‘vulnerability’ has expanded as a category through which we understand not only the nature of specific ‘vulnerable groups’ but, more generally, how the idea of the ‘vulnerable subject’ has become a more universal framework for understanding the human condition [

12].

Studies of student vulnerabilities are often engaged with through a psychological lens and, to some extent, are taken at face value where, for example, stress levels of students are studied in and of themselves to better understand the student experience [

13]. In this paper, we take a sociological approach that addresses the idea of student vulnerability as part of a cultural script, or a culturally constructed discourse within the therapeutic culture. Once established as a norm, in contradistinction to the robust liberal subject, or indeed to government minister’s pronouncements, the trend within universities is to understand students as primarily vulnerable subjects who need ‘safe spaces’, to protected them from certain ideas and to protect their emotional wellbeing [

14].

4. The Therapeutic University

The most comprehensive study of the significance of ‘vulnerability’ within universities comes in the book by Kathryn Ecclestone and Dennis Hayes entitled, The Dangerous Rise of Therapeutic Education [

50]. Here they incorporate an analysis of educational theory with the changing therapeutic practices within universities and the increasing elevation of the idea of vulnerability as a framework for governance and the management of both staff and students. In the chapter The therapeutic university, Ecclestone and Hayes argue that there are four processes that encourage vulnerability within universities: the elevated concerns about the vulnerability of students and staff, the rise of counselling courses, a new therapeutic philosophy of education and the rise of therapeutic teacher training. Additionally, they note that vulnerability takes a specific form within the academy, specific to the perceived emotional risk of dealing with intellectual ideas [

50] (p. 86).

Inter-related to these developments, the authors note the increasing infantilisation of students, the presumption that they cannot cope without some form of counselling and a move to think about students in classrooms and tutorials as potentially vulnerable [

50] (p. 87).

A new type of ‘support’ is now offered to students, and within this framework of therapeutic support, education itself—course work, essays and exams—are understood through the prism of “stress”. In other words, in part at least, the pursuit of knowledge has been pathologized. Consequently, the expectation of learning and the sense of excitement or striving associated with university life now competes with an institutionalised anxiety about the potentially damaging dimension of learning itself.

Facing criticism and contested ideas, Ecclestone and Hayes note, can now be seen as problematic. Quoting a ‘Guide to Students’ from counselling services, they note how subjects, like sociology, are seen as potentially stress inducing because they encourage students to “re-examine areas of their lives which have previously seemed unproblematic” [

50] (p. 92). Almost any challenge, pressure or even just changes in the lives and learning of students can now be reimagined as psychologically harmful, they argue.

Assisting these developments and this problematised approach to education, they note the increasing development of therapeutic education as a thing in itself, with university courses not only in counselling but also in ‘emotional literacy’ and ‘emotional well-being’ that have proliferated over the last two decades. By 2007, they noted that 517 colleges and universities were offering therapy related courses, a development that facilitated the accreditation of specific forms of therapeutic careers and that, more generally, helped to develop a “therapeutic ethos” within universities [

50] (p. 94), an ethos that is, again, in part, interconnected to the sense of the student as emotionally constituted and psychologically vulnerability.

Struggling to defend the classical idea of the university as a place specifically for the development of knowledge, enlightenment and the pursuit of truth, Ecclestone and Hayes note that academics like Stephen Rowland, who are attempting to develop a new philosophy of education, also adopt a form of emotionalism. Unable to defend the pursuit of knowledge as a thing in itself, Rowland falls into an alternative form of therapeutics in his defense of “intellectual love” and the “love [of] one’s subject” [

50] (p. 96). Rowland, they recognise, wants to defend subject based knowledge and the pursuit of truth but feels he can only do this by retreating inwards, into the inner world of emotions (of love) to do so.

The elevation of emotions and emotionalism in universities, they argue, undermines the ‘disinterested’ nature of academic life that is necessary for the pursuit of truth. What Ecclestone and Hayes are suggesting is that the pursuit of knowledge needs the individual to step outside of themselves, as best they can, to be a public individual rather than a private self, a thinking being rather than an emotional being, someone who stands above an issue and attempts to analyse it dispassionately rather than someone who is not capable of standing outside of themselves and their feelings. Today, the trend is for the inner focused perspective to become institutionalised through the various therapeutic process, practices and the shifting ethos within the academy.

Taking all of these developments together, what we end up with is a situation where the important act of skepticism and criticism of any and all ideas can be reinterpreted, from a feelings perspective, as a form of offense, and as hurtful. Consequently, the logic is for universities to encourage the inevitable clash of feelings to be examined and adjudicated through administrative processes and procedures, leading to a situation where disciplinary measures are triggered and used to regulate ‘offensive’ ideas and issues that emerge within the classroom.

Astutely predicting the therapeutic trends within universities, Ecclestone and Hayes argue that,

“None of these changes has anything positive to contribute to academic life. And they will get a firmer hold on the academy as the new generation of teacher-trained lecturers enters the profession influenced by sessions that emphasise the emotional side of working in higher education. Emotions, after all, cannot be questioned: they just are

One result is that academic freedom is weakened through this prism of vulnerability, due, in part, to the elevated significance given to the subjective feelings of students, or at least, some students. The outcome is the potential for “emotion wars”, where the most ‘hurt’ and ‘offended’ individuals increasingly come to determine the limits of intellectual engagement.

In the ‘Preface to the Classic Edition’ of The Dangerous Rise of Therapeutic Education, Kathryn Ecclestone and Dennis Hayes note that the pursuit of knowledge will potentially be undermined through changes within universities that elevate the anxiety about the “psychologically damaging consequences” of knowledge itself. Already, they noted, Buckingham University was being promoted as Britain’s first “positive” or “mindful” university. We find that by 2018, Sam Gyimah, the conservative minister for universities, gave an “ultimatum to vice-chancellors on student mental health, warning them it is not good enough to suggest that university is about academic education and nothing else”. As Ecclestone and Hayes note, this idea that universities, from the top down, must elevate the importance of mental wellbeing is not simply an add on to the pursuit of knowledge but turns this pursuit of knowledge into a potential problem for ‘vulnerable’ students. The pursuit of knowledge, they note, within this therapeutic framework, increasingly becomes something that is seen as “oppressive” [

50] (p. ix).

5. Findings

The nine interviews with lecturers in Scotland and England occurred in the first four months of 2021. The limited number of participants makes this a pilot project that can hopefully be built upon. Initially, three colleagues who I had worked with were contacted. All three were strong advocates of academic freedom and subsequently passed on details of (four) colleagues they thought it would be worth talking to about their experiences regarding academic freedom. From these four additional participants, a further two lecturers were passed on to me, thus developing a snowball sample of nine individuals, all of whom work in the humanities. Covering disciplines from politics and psychology to law and sociology, it is worth noting that it is often lecturers who discuss current social and political issues within their course who have the greatest concerns regarding limits to academic freedom. Due to Covid-19 restrictions these interviews took place via Zoom and through a number of telephone conversations. Consequently, there were some limitations to the interactive and personal nature of one-to-one in person interviews, but these were not felt to have limited the discussions or the nature of the interviews.

Despite some of the interviewees having expressed concerns about academic freedom prior to the interviews, when pushed to discuss the daily routine and experience of university life, most would talk about their work as “generally okay”, or even “weirdly fine”. The weirdness reflected, in part, to the fact that all lecturers spoken to were aware of the discussion about restrictions on academic freedom and all but two would see themselves as being strongly in favour of this freedom. Overall, the bulk of the time spent by these academics was not within a framework where the threat to academic freedom was a constant concern.

Psychology lecturer Carol, for example, explained, “I’m fine, more or less happy to cover any topic, as long as I’m well prepared. I think things are worse in the US. Although it’s becoming more of a thing, perhaps in general life over here, more than in academia”. Similarly, criminologist Christine said she “had not experienced any direct limits,” noting that it was, “more low level than that”.

For all of the lecturers, even those most concerned about academic freedom, limits to this freedom, at least at the level of teaching, was rarely overt. Stephanie, another psychologist, who taught in the area of mental health explained that she had, “never been told what to teach or what not to teach”.

One area where direct, or potentially direct censorship was experienced was with lecturers who taught Chinese students. China have passed a law making it possible for them to arrest anyone in the world who enters China and who is believed to have said something that threatens ‘national security’. The potential threat to Chinese students who express opinions while in the UK, and also to UK staff who teach in China, was felt to be considerable.

Paul, who teaches politics to Chinese students, explained that, “British universities have said nothing in relation to academic freedom and tend to want to stop you being too critical of China”.

Again, however, this limit was “rarely explicit”, more in the form of, “subtle concerns about guest speakers or things being “‘too’ political”. Paul had raised concerns about this with management but explained that, “My university tries to ignore it”, but “when you’re teaching international relations or politics you don’t want the Chinese students to say anything in case they’re put at risk”. For Paul, the irony was that with all the talk about ‘staff wellbeing’, when a serious risk of this nature comes along, “lecturers are exposed”, concerns raised are “never resolved”, and the university is “completely complicit”.

5.1. Controversy

Despite Carol, Christine and Stephanie all noting that things are ‘generally okay’ in their day-to-day work, they were also conscious that if the subject was controversial, they either found barriers to their work or felt nervous about how colleagues and management would react.

Christine, for example, who found her job, “weirdly fine”, also believed that one of her papers that was challenging aspects of critical race theory was dropped from a special edition of a journal because, “BLM [Black Lives Matter] had just kicked off”. She explained that following a conference presentation, she had been encouraged to write the paper, but the editor then explained that they would have to “send it to someone who knows more than we do about the subject! Then I heard nothing, and the journal was published without my paper. I think they were hoping I would just go away. Basically, I think they were saying we’re not publishing it because it makes us feel uncomfortable”.

For Christine, who talked about ‘low level’ pressure from her line manager, there was a conservatism regarding political issues, “even issues to do with culture and local councils’ economic priorities. If you even debate these critically at all, there’s background noise from your boss. They don’t say don’t do it, but there’s definitely a kind of ‘I’d rather you didn’t’ vibe to the whole thing”.

Law lecturer, James, described the experience of his colleague, Marcus, who had been “ostracised by people in the division who called him racist”. Marcus’ work questioned the narrative of Islamophobia surrounding a major government initiative. “Once it kicked off, he had three journals refuse to publish his work. People would talk about him behind his back, undermining him. He challenged them on the whole dignity of work policy. Some of the others care about their academic freedom but couldn’t give a shit about others. Academic[s] are in their personal silos. Yeah, defend their free speech but not others”.

Carol, who was “more or less happy to cover any topic”, also admitted that when it came to potentially controversial topics and how management and even some colleagues would react, she was, “worried how much they would be on your side. Would they back you?” Carol’s concern about the “general climate”, was elevated by examples she found within the British Psychological Society blog where there was a tendency for people to “pile-on rather than discuss things”. With one particular example, she explained that there had been a “massive pile-on, from quite senior academics”, against a colleague who “was taking issue with Black Lives Matter”. Carol said, “It felt almost cult like,” and explained after a pause that, “I’m worried about the direction BPS is going. I found it quite unsettling”. Carol was also conscious of the discussion about ‘decolonising the curriculum’ which wasn’t a major concern but was something that meant she felt the possibility of external pressure being used to ensure she adopted certain writers on her course that she would not automatically use. She explained that she was, “unsure what’s going to happen” with the decolonisation process and was concerned about “potentially being told to incorporate something [into the curriculum]”.

Christopher, a statistics lecturer working in England is another example of someone whose day-to-day work was “fine”, but he noted that he was more conscious now about certain topics. “I use examples, on the stats course, of dichotomous variables that divide things into two parts, and I used to use sex as an example. But I’ve stopped using it in case the trans issue is raised, or they say I’m being coercive, and that’s not an argument I want to have”. For Christopher, despite his general support for his work and the university, this self-censoring represented, “something quite problematic”.

Christopher, discussing his statistics students explained, “I’ve an email here from a student wanting to know if she can use the ‘N’ word in her dissertation. She’s looking at [the band] NWA. I didn’t know what to tell her”. Criminologist, Christine, noted, “I self-censor a bit with some staff and some students. I’m a bit wary of identity issues”.

Architecture lecturer, Alex, felt there were certain issues that were restricted or limited in some form, “like the environment”. Alex, whose work questions aspects of environmentalism within architecture, again explained that “it was less about direct restrictions [than] that some of my work is ignored in the division. It’s not like there’s a barrier but you can tell that nobody wants to discuss it or have a discussion or presentation about it”. Within architecture, Alex felt that the professional body, the Royal Institute of British Architects, that oversaw the degree programme, had adopted a certain uncritical approach to environmentalism within the profession and was, “dictating content”, and that, “academia does what it’s told”, by this professional body. Consequently, issues and ideas developed out with academia, in a professional organisation with its own pressures, were potentially limiting certain perspectives on this course.

Malcolm, who occasionally acted as a union representative for lecturers, explained that he’d come across “a few cases where the equalities framework was being used by human resources and management with issues around race and the trans[exual] question”. He believed that, “They seem to want to find a reason to limit what lecturers say. They feel obliged under equalities [legislation]”. None of the cases discussed by Malcolm had resulted in disciplinary proceedings but these cases took the form of “semi-informal chats”. For Malcolm there was a “balancing act for the university” regarding student wellbeing, often seen in relation to the Equalities Act, and academic freedom. “It’s definitely a form of pressure,” he explained.

5.2. Low Level Cultural Filtering

Some of the examples given above involve what lecturers felt was a direct form of limits on speaking or writing, particularly around controversial issues. Most of the concerns, however, were more ‘low level’ and part of a ‘climate’ or what psychology lecturer Stephanie described as a form of “cultural filtering”.

Stephanie was conscious of certain issues of controversy but was also, due in part to her mental health teaching, sensitive to the ‘wellbeing framework’ that encouraged what she called a form of “cultural filtering” of work within the academy. Stephanie said, “I’m glad I’m not on Twitter because of the trans stuff. It’s a dark place.” Regarding academic work she noted that, “It’s more self-censoring. It’s not specific, more a kind of culture. I don’t want to get on the wrong side of the student body or the uni[versity]’s corporate message”.

The corporate message, for Stephanie, incorporated a range of ‘consumer’ issues that overlapped and were part of the equality framework. This can be synthetised with the expression “need to look after student wellbeing”. “We’ve moved from guidance of knowledge to wellbeing monitors,” she explained. “I’ve never been told, but with all the emails about it and the idea of not damaging the wellbeing of all student. How can you know everything that can set someone off? It’s like we’re guardians of their wellbeing. I don’t do it but some of my colleagues put disclaimers on slides. I sometimes do a ‘if anyone has been affected’ type statement, like on the TV, at the end of lectures. I guess I feel pressure to say, ‘support is available’, it’s kind of good practice. But it’s back covering. I worry about questioning the narrative of trauma, but my students need to think about this, they might become mental health nurses! Perhaps it’s my own lack of confidence?”

Part of the ‘culture’ was both an anxiety about whether managers and colleagues would defend you if you discussed a controversial topic, but this was also related to concerns about the ‘student body’.

Law lecturer James explained that his colleague, Jim, “says lecturers are now scared of students. Some of them leave their doors open when they have meetings with individual students”. James was animate about this. Referring to Agent Smith, the main antagonist in the Matrix film trilogy who can enter anybody within the Matrix and turn them into the enemy, James asserted, “I think of every student as a potential Mr. Smith. You censor yourself with your students, of course you do”. James’ distrust of his students was replicated and perhaps influenced by his concern about his colleagues. “This environment is not an environment of trust, where you can trust colleagues. They watch every word you say, so I have nothing to do with them”. For James, his experiences within the university were situated in the “neoliberal, no such thing as society world. We’re all fragmented. Individuals”.

Christine’s university encouraged students to use a specific webpage where you can anonymously report problematic incidents or events related to Covid-19 and issues of equality, diversity and offence. “It’s more the culture it creates,” she noted, “it distracts. Existing policies could be used. I guess I just don’t like the idea of ratting on other people anonymously, even if it’s well meant. Especially if the university then feels it has to do something [such as] investigate. It’s not a healthy environment”.

Malcolm was concerned that, “universities should embrace people like [Jordan] Peterson. You want academics to challenge everything but that’s not what’s happening”. Media Studies lecturer, Neve, who had been critical of certain transgender policies, explained that in a meeting with human resources, “they explained that I had a pastoral role, and if any student felt that they couldn’t approach me about a harassment issue, then I was in breach of contract. They didn’t do anything. Just making me ‘aware’. I mean they accepted I wouldn’t discriminate, and I’d do my job but if a student wouldn’t approach me because of something I said, that’s it. Breach of contract, because of a feeling. What can you do with that?”

Neve, in a partial defense of her university, explains that, “I suspect lots of complaints, they bat back, but it’s partly self-preservation. They worry if the issue becomes an issue they’ll be seen as partly responsible. It’s managerial. They’d rather controversies just went away”.

Christopher was concerned about the perceived need to be or seen to be sympathetic to the experiences of students. “If I want to look at issues in the news, like sectarianism, and want to discuss the myth of sectarianism. Will this mean I can be said to be unsympathetic if someone in the class has experienced sectarianism. Am I unsympathetic to the experience? Does it mean we can’t challenge the equalities framework–the legal and political framework. Seems very damaging to me”.

5.3. Day to Day

Despite many of the academics noting that academic freedom or the lack of it was not a constant concern at work, there were, nevertheless, a number of concerns raised about aspects of day-to-day work that did appear to impinge upon this freedom.

Module handbooks or descriptors, according to Paul, were, “weighed down with so much other stuff, on diversity policies, safety and ethical issues, disability and discrimination policies, and so much stuff on ‘types of learning’. We’ve got a ten-page document about how to write a module handbook. It mentions ‘learning’ about fifty times, explaining how to be ‘inclusive’ and ‘accessible’ to diverse needs and spells out that this is legal. It’s like a contract or a legal document, [it] talks about data protection issues and resources being used legally, all to ensure the correct learning experience”. Paul concluded by noting that, “it’s in every module. And then at the end, there’s your stuff, your teaching material, the actual course itself, hidden away. It’s deprioritising the academic voice. There’s so much guff, the core content is tiny, lectures are virtually invisible. The message the students get is that academic content is small. I doubt they read it but it’s a symbolic form of marginalising the importance of academic significance”.

Neve noted a similar problem in terms of module descriptors and talked about the, “Academic standards people, people who go over and over new descriptors. There’s loads of them employed. Just paperwork. It’s supposed to make you accountable. But they don’t really care”.

Other concerns were raised about the pressure of student feedback and with lower expectations on students to cope with work. Christine and James both raised concerns about management telling them they were being too “domineering” when marking. Both were questioned about student feedback where the lecturers were accused of asserting a “right answer” to certain questions. Stephanie felt that “student feedback is a powerful thing”. Carol felt that feedback was “generally okay but there is a culture about how to package it a certain way”. She continued, “There’s an underestimation of what students can take. Tough love perhaps, as a means of helping them grow–sometimes–too low an expectation of what students can handle”. Christine thought that, “It’s a bit of a pain, some students can’t work in groups or do certain things they’d be expected to in the real world, being allowed off assessments. Students at our place seem to regulate their relationship with the university through their wellbeing. We can’t mark for poor grammar for a lot of the students, but I do a bit. We’ve taken on administrative roles now, pastoral roles, like guidance teachers, we’re kind of expected to deal with mental health issues. It seems like this mental health approach is more the relationship between students and our university. I kind of worry about this a bit because it undermines the knowledge content and how you relate to it”.

6. Conclusions

As we ‘go to press’, two campaigns have just started to have lecturers ‘cancelled’; one aims to sack the supposed anti-Semite Professor David Miller; the other targets the claimed Islamophobe Professor Steven Greer. In the petition against the latter, it is argued that Bristol University must act upon its “policies to protect its students,” something that must be ‘‘balanced’ with “academic freedom”. Here the speech quotes around academic freedom are used to question the very idea of academic freedom, something that comes a distant second to the need for universities to do as they claim and protect their students.

Are universities places that, as the UK education secretary Gavin Williamson suggests, should be open to outlandish, provocative or uncomfortable ideas? Moreover, is the ideal of academic freedom promoted in the Declaration of Principles, on academic freedom and tenure, a reality? If not, what are the barriers to this?

The research here would suggest that there are new limits and restrictions that academics face. These are rarely generated by external forces where overt restrictions are enforced, although we do see this with the example of China. Where there are thought to be direct limits on work, these came in the form of academic journals not publishing certain ‘controversial’ work, although this cannot be proven to be the case. The Prevent Strategy and the Equalities Act 2010 could be seen as external restrictions, although nobody here mentioned Prevent. The equalities framework on the other hand was mentioned by a number of the interviewees, and this framework of engaging with the idea of being ‘offended’, often with reference to ‘protected characteristics’, does appear to be of some significance [

51].

University equality and diversity policies discuss the need to ensure ‘dignity and respect’, something that is related to concerns about ‘harassment and bullying’. Many universities attempt to deal with these problems through “mandatory diversity awareness training”; but what if dignity and respect is understood to relate to ideas or even attitudes of lecturers? Does this create a crossover of diversity-based issues with a human resource management of student wellbeing?

Controversial ideas and issues were important in terms of the potential for staff to be or to feel that they had limits placed upon them or where they felt they should limit themselves. However, this is unlike the Chinese example, where the Chinese Government is looking at particular ideas that are seen as harmful to the state. Here, in the UK, it is the perceived harm to the student that appears to raise most concerns and potentially limit the freedom of academics to use their own judgement in their day-to-day activities. Any idea that is understood to make students feel ‘uncomfortable’ or ‘excluded’ becomes possible grounds for concern and possibly even administrative and management intervention. More generally, it is not simply that certain ideas are problematised but certain academic behaviours are also labelled as being ‘unsympathetic’ or ‘domineering’ and are regulated in terms of marking, feedback or expectations of correct lecturing practices.

Although some of those interviewed talked about being ‘scared’ of students, the term scared seems, at times, to be too extreme, and in general, it would be more accurate to talk about a low-level form of anxiety or unsureness amongst the lecturers. This is related to particular issues, like racism or transgender questions that impacted on lecturers in terms of self-censoring with students, and also to a nervousness with regard to both management and fellow staff member not ‘having your back’.

A nervousness also related, for some, with what was seen as the human resources management of ‘diversity and equality’ issues within the wellbeing framework. Here, as Ecclestone and Hayes have observed, we find a more therapeutic form of management, where the emotional wellbeing of students is understood to be threatened by lecturers whose ideas are seen to be lacking ‘respect’ or threatening the ‘dignity’ and therefore the wellbeing of students.

The wellbeing framework, and the need to protect vulnerable students, in this respect, appears to be a significant factor that impacts academic freedom. Nevertheless, it is rare for this to come in the form of an overt or directed challenge to individual lecturers, although this appears to be increasing, and high-profile cases help to create a climate of anxiety. More generally, we find a form of cultural filtering, a consciousness of appropriate behaviour, assisted by a symbolic squeezing out of the knowledge framework by a myriad of procedures and ‘correct’ forms of learning, for instance when writing module handbooks, marking, giving feedback and in some cases when giving lectures.

Rather than the use of overt force, here we find a ‘softer’ form of limits, as the guidance of knowledge is supplemented and to some degree usurped by the need to become wellbeing monitors. This, to some extent, can be described as a form of walking on egg-shells, where an unsureness of openness about certain issues with students and with colleagues and management coalesces with new ‘respectful’ ways to relate to student wellbeing. The result is that day-to-day aspects of work have become framed less through professional judgement of what is best for education and the development of knowledge and more with reference to what is ‘appropriate’ and ‘inclusive’ and ‘supportive’ of the ‘student experience’ and their emotional wellbeing.

Within this climate, regardless of what Gavin Williamson says, making students feel ‘uncomfortable’ can be problematic. Concerns about student wellbeing can limit what issues and ideas lecturers engage with. Indeed, making students feel uncomfortable is antithetical to an approach that engages with the student body through the prism of vulnerability. This is particularly problematic, giving the potential pedagogical benefits of challenging students’ perspectives, even when this is potentially awkward or unpleasant for the student. In this respect, where universities engage with students as vulnerable, we find a new form of pressure or cultural filtering. Consequently, the very practices that are understood to benefit the wellbeing of the student may well act to prevent students from really learning.

A final observation with regard to the pursuit of truth and academic freedom: The ideal of academic freedom encourages an open-ended, experimental and risk-taking approach to university education and research that results in an externally oriented approach to knowledge that is open to criticism. Today, the culture of universities appears to be far more risk averse, more closed to certain questions and even behaviours, something that is more introspective—inner rather than externally oriented—increasingly concerned with the inner-self, the emotional wellbeing of students and with the therapeutic management of the student experience. Rather than encouraging a spirit of discovery, this approach encourages the opposite (concealment) where risks are there to be avoided or managed rather than pushed and explored. If the vulnerable student becomes central to ‘good practices’ within universities, freedom for academics, in more and more areas of their work will become increasingly problematic. Indeed, academic freedom becomes a problem, a risk, a source of potential anxiety for students, managers and lecturers—academic freedom becomes antithetical to the ‘good’ university.