Incorporating Survey Perceptions of Public Safety and Security Variables in Crime Rate Analyses for the Visegrád Group (V4) Countries of Central Europe

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Criminal Statistics and Public Perceptions: Data, Mapping, and Analytics

2.2. Urban Security Management: Social Control Policies and Strategies

2.3. Smart Safety and Security Governance in the Digital Age

3. Research Questions

3.1. Main Objectives

3.2. Research Questions

3.3. Hypotheses

4. Methodology

4.1. Data Analysis and Analyzed Questionnaire

4.2. Ethical Aspect of Study

4.3. Definition of Variables

5. Results

Crime Rates and Safety Perceptions: A Spatiotemporal Analysis of V4 Countries (2013–2019)

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hipp, J.R. Assessing crime as a problem: The relationship between residents’ perception of crime and official crime rates over 25 years. Crime Delinq. 2013, 59, 616–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardanaz, M. Mind the Gap: Bridging Perception and Reality with Crime Information; American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Spicer, V.; Song, J.; Brantingham, P. Bridging the perceptual gap: Variations in crime perception of businesses at the neighborhood level. Secur. Inform. 2014, 3, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, U.; Toth, P.; David, F. A Comparative Review On Public Safety And Security Indicator(S) Gaps In Smart Cities’ Indexes. In Proceedings of the 12th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Online, 23–25 September 2021; pp. 621–630, ISBN 978-1-6654-2494-3. [Google Scholar]

- Judt, T. Ill Fares the Land; Penguin: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goold, B.J. Privacy rights and public spaces: CCTV and the problem of the “unobservable observer”. Crim. Justice Ethics 2002, 21, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, G.V.; Parycek, P.; Falco, E.; Kleinhans, R. Smart governance in the context of smart cities: A literature review. Inf. Polity 2018, 23, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, F.; Useche, S.; Faus, M.; Esteban, C. Does Urban Security Modulate Transportation Choices and Travel Behavior of Citizens? A National Study in the Dominican Republic. Front. Sustain. Cities 2020, 2, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solymosi, R.; Buil-Gil, D.; Vozmediano, L.; Guedes, I.S. Towards a Place-based Measure of Fear of Crime: A Systematic Review of App-based and Crowdsourcing Approaches. Environ. Behav. 2020, 53, 1013–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, J. Integrating Sketch Maps with GIS to Explore Fear of Crime in the Urban Environment: A Review of the Past and Prospects for the Future. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2012, 39, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butot, V.; Bayerl, P.S.; Jacobs, G.; de Haan, F. Citizen repertoires of smart urban safety: Perspectives from Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 158, 120164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulumello, S. The multiscalar nature of urban security and public safety: Crime prevention from local policy to policing in Lisbon (Portugal) and Memphis (the United States). Urban Aff. Rev. 2018, 54, 1134–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, B.; Wood, J. Urban security, from nodes to networks: On the value of connecting disciplines. Can. J. Law Soc. Rev. Can. Droit Société 2007, 22, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, D.M.; Bernstein, D. Benefits and Best Practices of Safe City Innovation; Center for Technology Innovation at Brookings: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobi, Á.; Pődör, A. GIS-Based Statistical Analysis of Detecting Fear of Crime with Digital Sketch Maps: A Hungarian Multicity Study. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, T. The effectiveness of a police-initiated fear-reducing strategy. Br. J. Criminol. 1991, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozmediano, L.; Azanza, M.; Villamane, M. Desarrollando y Probando Una App Para Analizar La Influencia de La Se-guridad Percibida En La Movilidad a Pie: Un Trabajo Multidisciplinary Con Profesorado y Alumnado de Psicología e Ingeniería. Educ. Base Para Los Objet. Desarro. Sosten. Grupo 2017, 4, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Mohler, G.; Porter, M.D. Rotational Grid, PAI-Maximizing Crime Forecasts. Statistical Analysis and Data Mining. ASA Data Sci. J. 2018, 11, 227–236. [Google Scholar]

- Nummenmaa, L.; Hari, R.; Hietanen, J.K.; Glerean, E. Maps of subjective feelings. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 9198–9203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounadi, O.; Ristea, A.; Araujo, A.; Leitner, M. A systematic review on spatial crime forecasting. Crime Sci. 2020, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, N.; Lukinbeal, C. Comparing Police and Residents’ Perceptions of Crime in a Phoenix Neighborhood using Mental Maps in GIS. Yearb. Assoc. Pac. Coast Geogr. 2010, 72, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, D.; Ray, H. (Eds.) Images of the urban environment. In Images of the Urban Environment; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, L.W.; Caplan, J.M.; Piza, E. Risk clusters, hotspots, and spatial intelligence: Risk terrain modeling as an algorithm for police resource allocation strategies. J. Quant. Criminol. 2011, 27, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugato, M.; Favarin, S.; Bosisio, A. Isolating Target And Neighbourhood Vulnerabilities In Crime Forecasting. Eur. J. Crim. Policy Res. 2018, 24, 393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Maciejewski, R.; Towers, S.; McCullough, S.; Ebert, D.S. Proactive Spatiotemporal Resource Allocation and Predictive Visual Analytics for Community Policing and Law Enforcement. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2014, 20, 1863–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.M. The ‘Surveillance Society’ Questions of History, Place and Culture. Eur. J. Criminol. 2009, 6, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R.G. Holistic strategy for urban security. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2004, 10, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhan, D.; Kwan, M.P.; Zhang, W.; Fan, J.; Yu, J.; Dang, Y. Assessment and determi-nants of satisfaction with urban livability in China. Cities 2018, 79, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.; Bradford, B.; Hough, M.; Kuha, J.; Stares, S.; Widdop, S.; Fitzgerald, R.; Yordanova, M.; Galev, T. Developing European indicators of trust in justice. Eur. J. Criminol. 2011, 8, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šelih, A. Crime and crime control in transition countries. In Crime and Transition in Central and Eastern Europe; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Altindag, D.T. Crime and unemployment: Evidence from Europe. Int. Rev. Law Econ. 2012, 32, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelnovo, W.; Misuraca, G.; Savoldelli, A. Smart Cities Governance: The Need for a Holistic Approach to Assessing Urban Participatory Policy Making. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2016, 34, 724–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GruszczyŃska, B. Crime in Central and Eastern European Countries in the Enlarged Europe. Eur. J. Crim. Policy Res. 2004, 10, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skog, D.A.; Henrik, W.; Johan, S. Digital disruption. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2018, 60, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.; Henfridsson, O.; Lyytinen, K. Research commentary—The new organizing logic of digital innovation: An agenda for information systems research. Inf. Syst. Res. 2010, 21, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Lyytinen, K.; Majchrzak, A.; Song, M. Digital Innovation Management: Reinventing innovation management research in a digital world. MIS Q. 2017, 41, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichman, R.G.; Dos Santos, B.L.; Zheng, Z. Digital innovation as a fundamental and powerful concept in the information systems curriculum. MIS Q. 2014, 38, 329-A15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilson, D.; Lyytinen, K.; Sørensen, C. Research commentary—Digital infrastructures: The missing IS research agenda. Inf. Syst. Res. 2010, 21, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.D.; Bowers, K.J. The Burglary as Clue to the Future: The Beginnings of Prospective Hot-Spotting. Eur. J. Criminol. 2004, 1, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariel, B.; Sutherland, A.; Henstock, D.; Young, J.; Drover, P.; Sykes, J.; Megicks, S.; Henderson, R. Report: Increases in police use of force in the presence of body-worn cameras are driven by officer discretion: A protocol-based subgroup analysis of ten randomized experiments. J. Exp. Criminol. 2016, 12, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourabi, H.; Nam, T.; Walker, S.; Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Mellouli, S.; Nahon, K.; Pardo, T.A.; Scholl, H.J. Understanding Smart Cities: An Integrative Framework. In Proceedings of the 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Makhoul, N. From Sustainable to Resilient and Smart Cities. In IABSE Reports; International Association for Bridge and Structural Engineering (IABSE): Zurich, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, D.B.; Moretti, A.; Shlomo, N.; Medina, J. Worry about crime in Europe: A model-based small area estimation from the European Social Survey. Eur. J. Criminol. 2019, 18, 274–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, E.; Jackson, J.; Farrall, S. Reassessing the Fear of Crime. Eur. J. Criminol. 2008, 5, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseloni, A.; Zarafonitou, C. Fear of Crime and Victimization: A Multivariate Multilevel Analysis of Competing Measurements. Eur. J. Criminol. 2008, 5, 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kury, H. Postawy Punitywne i Ich Znaczenie Punitive Attitudes and Their Meaning. In Mit Represyjności Albo o Znaczeniu Prewencji Kryminalnej; Czapska, J., Kury, H., Eds.; Zakamycze: Krakow, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Public Database VDB. n.d. Czso.Cz. Available online: https://vdb.czso.cz/vdbvo2/faces/en/index.jsf?page=vystup- (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- BSR. n.d. Bsr.Bm.Hu. Available online: https://bsr.bm.hu/Document (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Polska Policja. n.d. “Statystyka”. Statystyka. Available online: http://statystyka.policja.pl/ (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Poland: Recorded and Detected Crimes 2021. n.d. Statista. Available online: http://www.statista.com/statistics/1120240/poland-recorded-and-detected-crimes/ (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Annual Budget of Frontex in the EU 2005–2021. n.d. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/973052/annual-budget-frontex-eu/ (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- N.d. Statistics.Sk. Available online: https://statdat.statistics.sk (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Van der Woude, M.; Barker, V.; Van Der Leun, J. Crimmigration in Europe. Eur. J. Criminol. 2017, 14, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N.d. Europeansocialsurvey.org. Available online: https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/ (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Levay, M. Social Exclusion: A Prosperous Term in Contemporary Criminology; Social Exclusion and Crime in Central and Eastern Europe. Ann. U. Sci. Bp. Rolando Eotvos Nomin. 2006, 47, 119. [Google Scholar]

- Bronowska, K.; Sławik, K. Przestępczość a środki masowego przekazu. Problemy Współczesnej Kryminalistyki 2003, 6, 257–273. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, S.C. The value of reducing fear: An analysis using the European Social Survey. Appl. Econ. 2006, 38, 115–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidov, E. A Cross-Country and Cross-Time Comparison of the Human Values Measurements with the Second Round of the European Social Survey. Surv. Res. Methods 2008, 2, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leman-Langlois, S. Introduction: Technocrime. In Technocrime: Technology, Crime and Social Control; Leman-Langlois, S., Ed.; Willan Publishing: Cullompton, UK, 2008; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hungarian Central Statistical Office. n.d. Ksh.Hu. Available online: https://www.ksh.hu/justice (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- n.d. Europa.Eu. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/crim_off_cat$DV_348/default/table?la (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Polizeiliche Kriminalstatistik (PKS). n.d. Bundeskriminalamt. Available online: https://bundeskriminalamt.at/501/ (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- World Development Indicators; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

| Spearman’s Rho Correlations | CR19 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman’s rho | CR19 | Correlation coefficient | 1.000 |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.0 | ||

| N | 6642 | ||

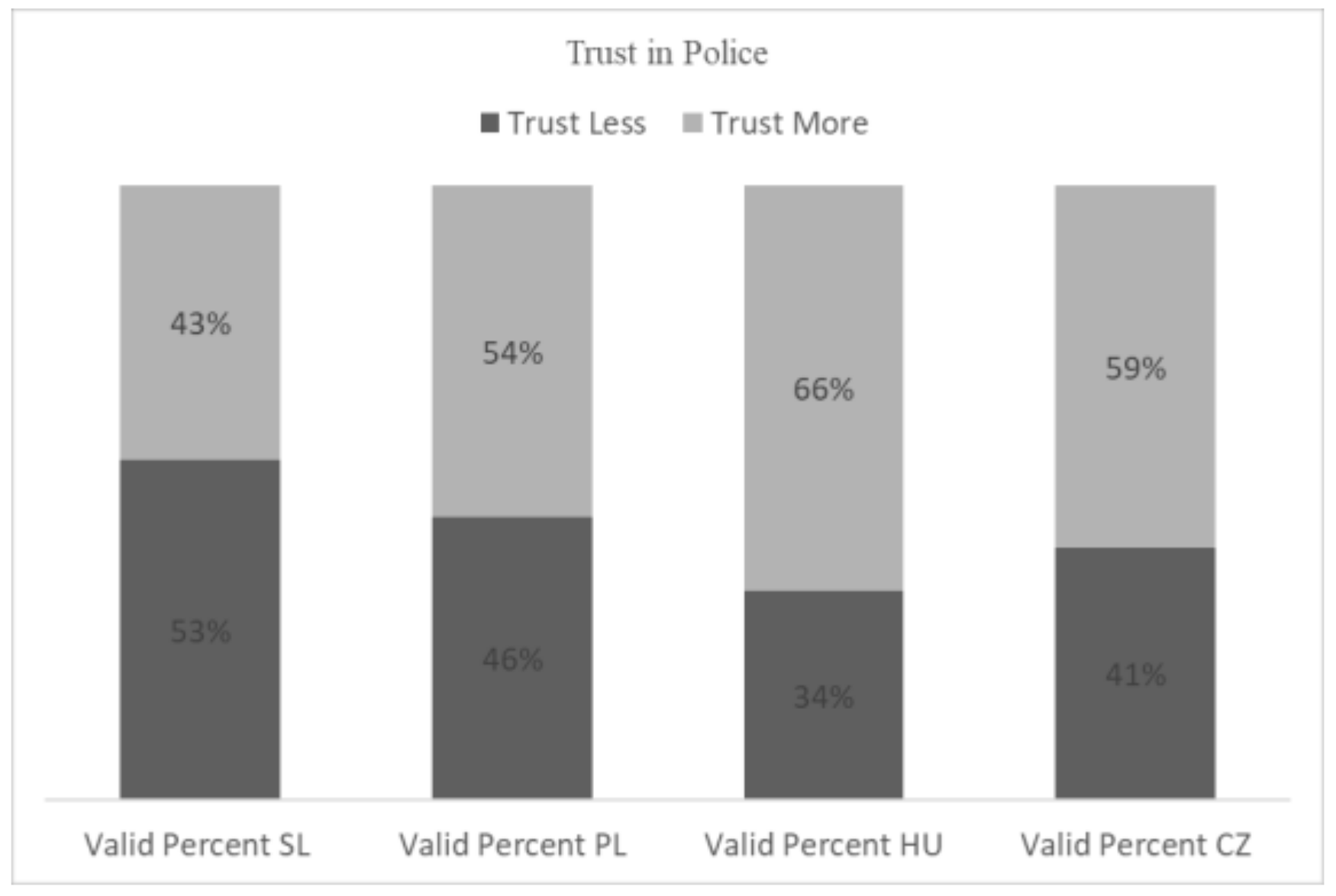

| Trust in the police | Correlation coefficient | 0.068 ** | |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.000 | ||

| N | 6569 | ||

| Respondent’s sequence number in cumulative dataset | Correlation coefficient | 0.107 ** | |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.000 | ||

| N | 6642 | ||

| Respondent or household member was a victim of burglary/assault in the last 5 years | Correlation coefficient | 0.031 * | |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.013 | ||

| N | 6615 | ||

| Feeling of safety when walking alone in the local area after dark | Correlation coefficient | −0.133 ** | |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.000 | ||

| N | 6563 | ||

| Importance of living in secure and safe surroundings | Correlation coefficient | 0.009 | |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.484 | ||

| N | 6526 | ||

| Importance of doing as told and following rules | Correlation coefficient | 0.045 ** | |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.000 | ||

| N | 6467 | ||

| Importance of a government that is strong and ensures safety | Correlation coefficient | 0.056 ** | |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.000 | ||

| N | 6490 | ||

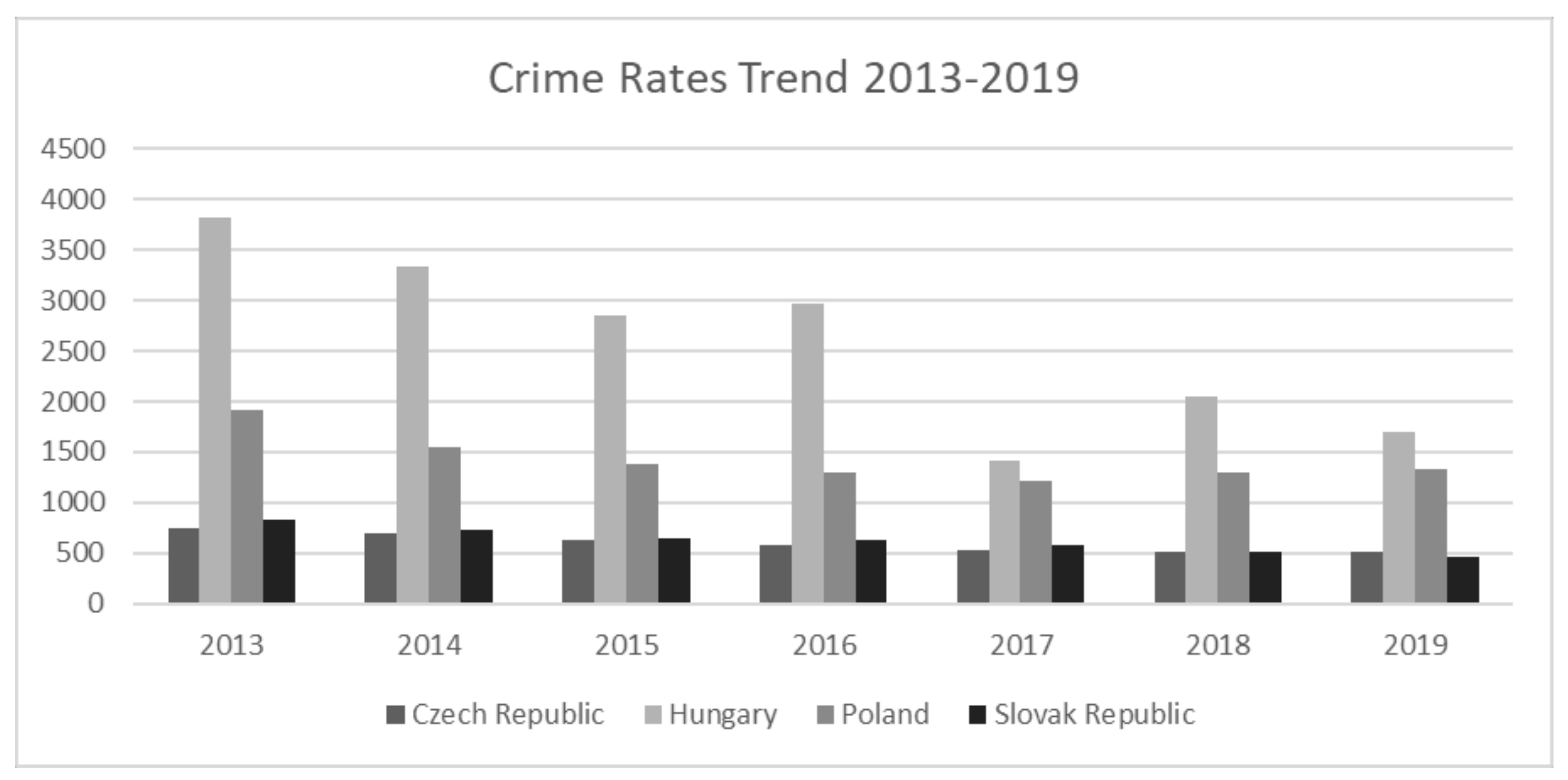

| Crime Count | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Czech Republic | 77,976 | 72,825 | 65,569 | 61,423 | 55,705 | 54,448 | 55,594 |

| Hungary | 377,829 | 329,575 | 280,113 | 290,779 | 138,199 | 199,830 | 165,648 |

| Poland | 727,700 | 589,100 | 522,500 | 490,300 | 463,900 | 491,700 | 507,200 |

| Slovak Republic | 44,753 | 39,938 | 34,780 | 33,822 | 31,286 | 27,568 | 25,123 |

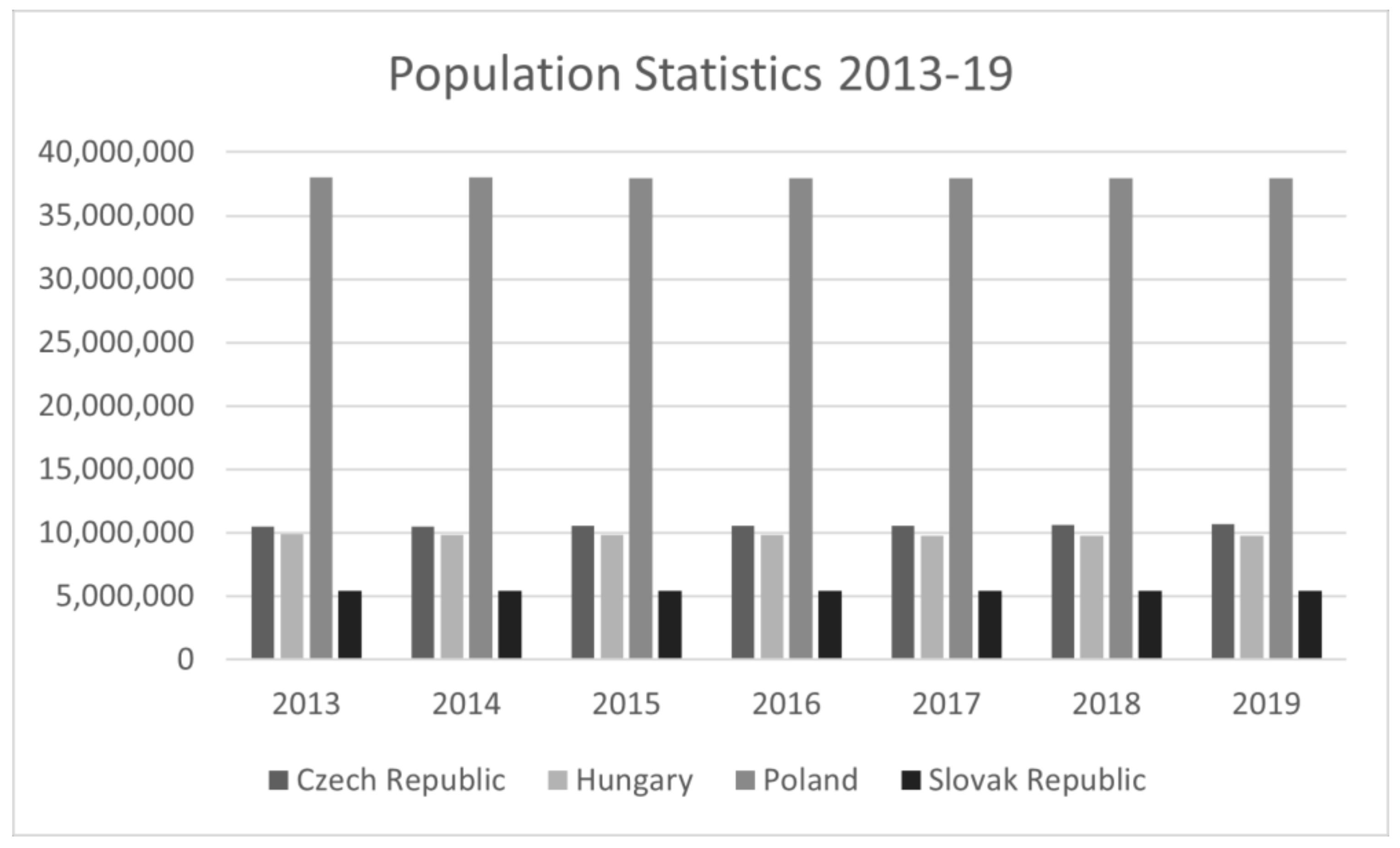

| Population 1 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

| Czech Republic | 10,514,272 | 10,525,347 | 10,546,059 | 10,566,332 | 10,594,438 | 10,629,928 | 10,671,870 |

| Hungary | 9,893,082 | 9,866,468 | 9,843,028 | 9,814,023 | 9,787,966 | 9,775,564 | 9,771,141 |

| Poland | 38,040,196 | 38,011,735 | 37,986,412 | 37,970,087 | 37,974,826 | 37,974,750 | 37,965,475 |

| Slovak Republic | 5,413,393 | 5,418,649 | 5,423,801 | 5,430,798 | 5,439,232 | 5,446,771 | 54,54,147 |

| Crime Rates | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

| Czech Republic | 741.6205 | 691.9012 | 621.7394 | 581.3086 | 525.7948 | 512.2142 | 520.9396 |

| Hungary | 3819.123 | 3340.354 | 2845.801 | 2962.893 | 1411.928 | 2044.179 | 1695.278 |

| Poland | 1912.976 | 1549.785 | 1375.492 | 1291.28 | 1221.599 | 1294.808 | 1335.951 |

| Slovak Republic | 826.7089 | 737.0472 | 641.2477 | 622.7814 | 575.1915 | 506.1347 | 460.622 |

| Czech Republic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

| Illegal production and possession of narcotics, psychotropic substances, and poisons; spreading of addiction | 2522 | 2854 | 2708 | 2833 | 2837 | 2868 | 3103 |

| Evasion of alimony payments | 11,154 | 9803 | 8160 | 7339 | 6063 | 5249 | 5272 |

| Cruelty to a person sharing the dwelling or house | 291 | 285 | 252 | 255 | 252 | 235 | 226 |

| Murder | 121 | 132 | 112 | 96 | 75 | 99 | 74 |

| Bodily harm, brawling | 4528 | 2971 | 2870 | 2993 | 2780 | 2822 | 2738 |

| Robbery | 1388 | 1106 | 1007 | 908 | 775 | 763 | 764 |

| Rape and sexual abuse | 535 | 529 | 515 | 593 | 557 | 580 | 600 |

| Theft, embezzlement, fraud | 25,052 | 23,032 | 18,847 | 16,819 | 15,398 | 14,364 | 14,162 |

| Traffic offences | 16,903 | 16,715 | 16,055 | 18,698 | 13,840 | 14,337 | 15,935 |

| Other offences | 50,460 | 48,516 | 45,770 | 43,165 | 38,939 | 39,068 | 40,727 |

| Total crime | 77,976 | 72,825 | 65,569 | 61,423 | 55,705 | 54,448 | 55,594 |

| Poland | |||||||

| Year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

| Recorded crimes | 727,700 | 589,100 | 522,500 | 490,300 | 463,900 | 491,700 | 507,200 |

| Detected crimes | 406,900 | 317,800 | 275,500 | 272,700 | 281,000 | 319,200 | 332,800 |

| Hungary | |||||||

| Year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

| Grand total | 377,829 | 329,575 | 280,113 | 290,779 | 138,199 | 199,830 | 165,648 |

| Slovak Republic | |||||||

| Year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

| Crimes of violence | 6003 | 5637 | 5686 | 6382 | 6132 | 5781 | 5540 |

| Murder | 78 | 72 | 48 | 60 | 80 | 67 | 76 |

| Robbery | 836 | 680 | 539 | 526 | 469 | 475 | 410 |

| Battery | 2017 | 1955 | 1862 | 1632 | 1618 | 1599 | 1526 |

| Rape | 91 | 87 | 87 | 82 | 96 | 99 | 97 |

| Property crimes | 38,750 | 34,301 | 29,094 | 27,440 | 25,154 | 21,787 | 19,583 |

| Burglary | 11,167 | 9427 | 6862 | 6260 | 5720 | 4529 | 3695 |

| Motor vehicle theft | 2431 | 2297 | 1932 | 1671 | 1524 | 1339 | 1042 |

| Total | 44,753 | 39,938 | 34,780 | 33,822 | 31,286 | 27,568 | 25,123 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghani, U.; Toth, P.; Fekete, D. Incorporating Survey Perceptions of Public Safety and Security Variables in Crime Rate Analyses for the Visegrád Group (V4) Countries of Central Europe. Societies 2022, 12, 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060156

Ghani U, Toth P, Fekete D. Incorporating Survey Perceptions of Public Safety and Security Variables in Crime Rate Analyses for the Visegrád Group (V4) Countries of Central Europe. Societies. 2022; 12(6):156. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060156

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhani, Usman, Peter Toth, and Dávid Fekete. 2022. "Incorporating Survey Perceptions of Public Safety and Security Variables in Crime Rate Analyses for the Visegrád Group (V4) Countries of Central Europe" Societies 12, no. 6: 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060156

APA StyleGhani, U., Toth, P., & Fekete, D. (2022). Incorporating Survey Perceptions of Public Safety and Security Variables in Crime Rate Analyses for the Visegrád Group (V4) Countries of Central Europe. Societies, 12(6), 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060156