Family and Youth Development: Some Concepts and Findings Linked to The Ecocultural and Acculturation Models †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

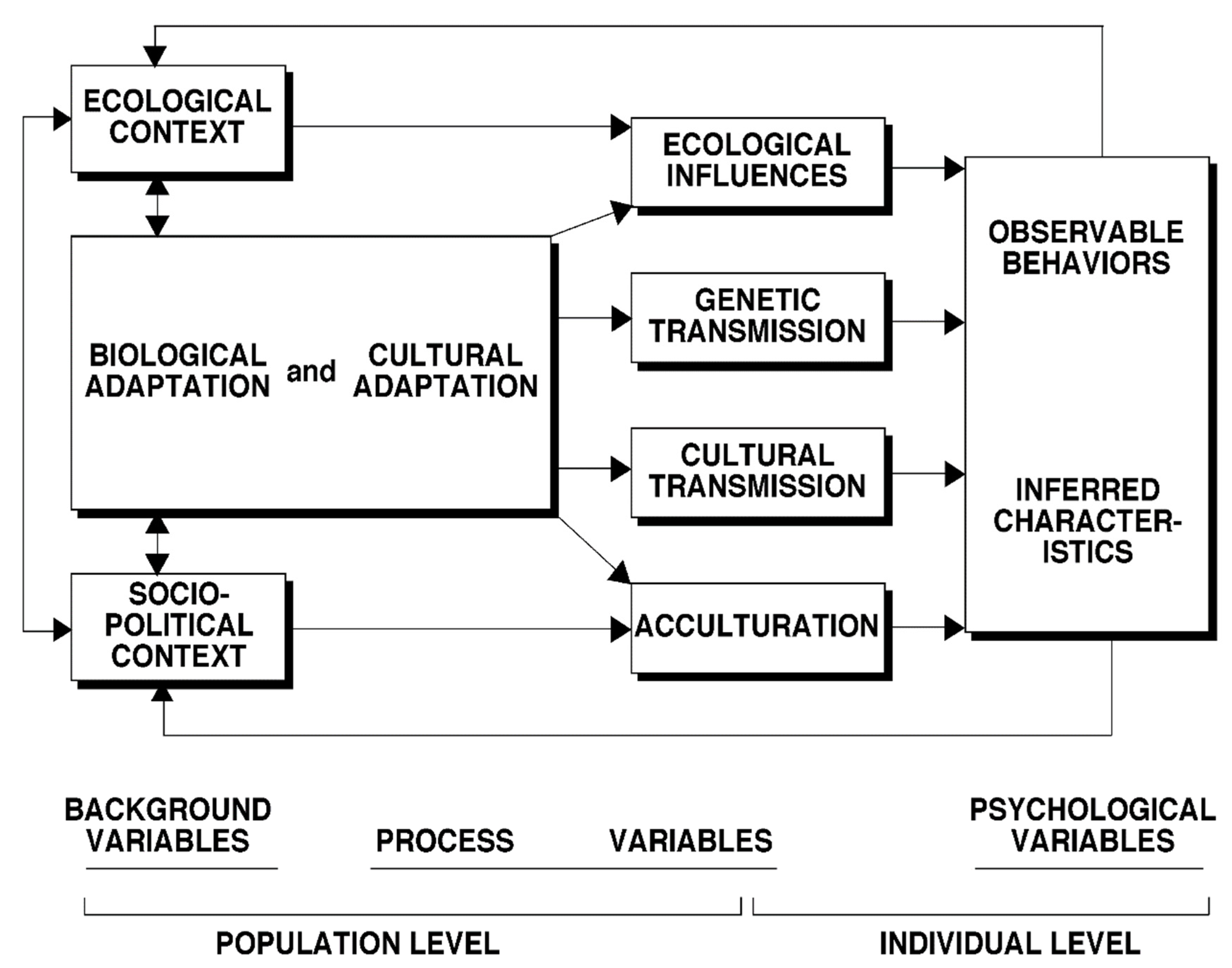

2.1. Ecocultural Approach

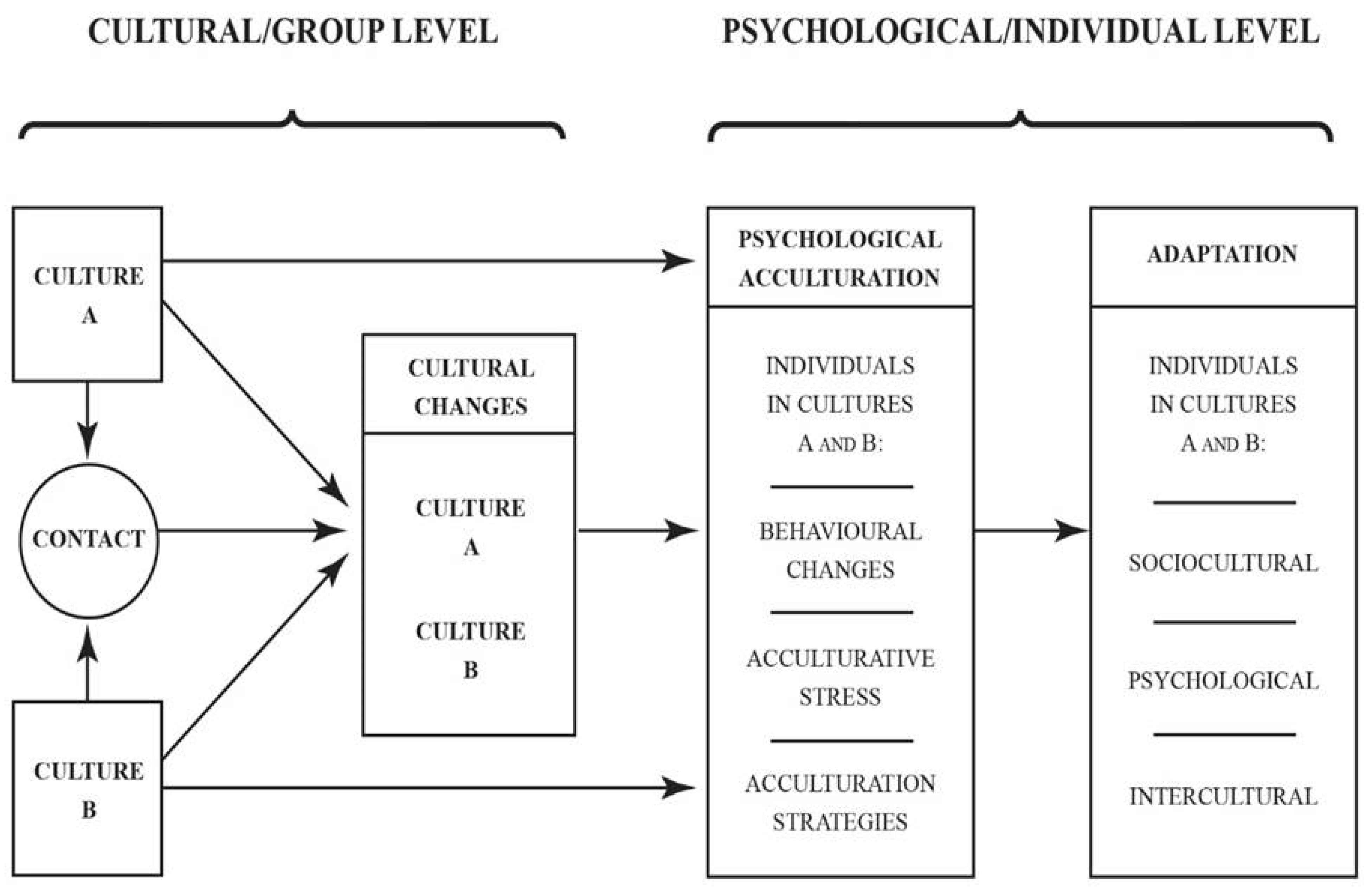

2.2. Acculturation and Adaptation

2.3. Acculturation Strategies

2.4. Acculturation and Cultural Transmission

3. Results and Discussion: Some Empirical Examples

3.1. Enculturation

3.2. Family Structure

3.3. Families across Cultures

3.3.1. Affluence

3.3.2. Family Roles

3.3.3. Family Relationship Values

3.4. Immigrant Youth

4. Conclusions and Implications

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Motti-Stefanidi, F.; Berry, J.W.; Chryssochoou, X.; Sam, D.L.; Phinney, J. Positive immigrant youth adaptation in context: Developmental, acculturation, and social psychological perspectives. In Capitalizing on Migration: The Potential of Immigrant Youth; Masten, A., Liebkind, K., Hernandez, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 117–158. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological systems theory. Ann. Child Dev. 1989, 6, 185–246. [Google Scholar]

- Super, C.M.; Harkness, S. The development niche: Aconceptualization at the interface of child and culture. Int. Behav. Dev. 1986, 9, 545569. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting, J.W.M. A model for psychocultural research. In Culture and Infancy: Variations in the Human Experience; Leiderman, P.H., Tulkin, S.R., Rosenfeld, A., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Vliert, E. Climates Create Cultures. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2007, 1, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Vliert, E. Human Cultures as Niche Constructions Within the Solar System. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2016, 47, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Welzel, C.; Kruse, S.; Brieger, S.A.; Brunkert, L. The Cool Water Effect: Geo-Climatic Origins of the West’s Emancipatory Drive. 2021. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3 (accessed on 17 November 2022).

- Berry, J.W. Human Ecology and Cognitive Style: Comparative Studies in Cultural and Psychological Adaptation; Sage/Halsted: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W. Ecological perspective on human behaviour. In Socio-Economic Environment and Human Psychology; Uskul, A., Oishi, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W. Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2005, 29, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, A.S.; Kunst, J.R.; Sam, D.L. Climatic effects on the sociocultural and psychological adaptation of migrants within China: A longitudinal test of two competing perspectives. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 22, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgas, J.; Mylonas, K.; Bafiti, T.; Poortinga, Y.H.; Christakopoulou, S.; Kagitcibasi, C.; Kodiç, Y. Functional relationships in the nuclear and extended family: A 16-culture study. Int. J. Psychol. 2001, 36, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgas, J.; Berry, J.W.; van de Vijver Kagitcibasi, C.; Poortinga, Y.H. (Eds.) Family Structure and Function: A 30 Nation Psychological Study; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Georgas, J.; Berry, J.W. An ecocultural taxonomy for cross-cultural psychology. Cross-Cult. Res. 1995, 29, 121–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgas, J.; van de Vijver, F.; Berry, J.W. The ecocultural framework, ecosocial indices and psychological variables in cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psyc. 2004, 35, 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagitcibasi, C. Family, Self and Human Development Across Cultures, 2nd ed.; LEA: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kagitcibasi, C.; Ataca, B. Value of Children and Family Change: A Three Decade Portrait From Turkey. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 54, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redfield, R.; Linton, R.; Herskovits, M.J. Memorandum on the study of acculturation. Am. Anthropol. 1936, 38, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, T.D. Psychological acculturation in a tri-ethnic community. South-West J. Anthropol. 1967, 23, 337–350. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, G.M.; Iturbide, M.I.; Raffaelli, M. Proximal and remote acculturation: Adolescents’ perspectives of biculturalism in two contexts. J. Adolesc. Res. 2019, 35, 431–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, K.; Berry, J.W. Generational differences in acculturation among Asian families in Canada. Int. J. Psychol. 2001, 36, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatier, C.; Berry, J.W. The role of family acculturation, parental style and perceived discrimination in the adaptation of second generation immigrant youth in France and Canada. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 5, 159–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataca, B.; Berry, J.W. Psychological, sociocultural and martial adaptation of Turkish immigrant couples in Canada. Int. J. Psychol. 2002, 37, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, D.L.; Berry, J.W. (Eds.) Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W.; Hart Hansen, J.P. Problems of family health in Circumpolar regions. Arct. Med. Res. 1985, 40, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.; Zheng, Y.; Berry, J.W. Differences in resilience by acculturation strategies: A study with Qiang nationality following the 2008 Chinese earthquake. Int. J. Emerg. Ment. Health 2016, 17, 573–580. [Google Scholar]

- Kruusvall JVetik, R.; Berry, J.W. The strategies of inter-ethnic adaptation of Estonian Russians. Stud. Transit. States Soc. 2009, 1, 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W. Acculturation as varieties of adaptation. In Acculturation: Theory, Models and Some New Findings; Padilla, A., Ed.; Westview: Boulder, CO, USA, 1980; pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W. Immigration, acculturation and adaptation. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 1997, 46, 5–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W. (Ed.) Mutual Intercultural Relations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vedder, P.; Berry, J.W.; Sabatier, C.; Sam, D. The intergenerational transmission of values in national and immigrant families: The role Zeitgeist. J. Youth Adolesc. 2009, 38, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barry, H.; Child, I.; Bacon, M. Relation of child training to subsistence economy. Am. Anthropol. 1959, 61, 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W.; Phinney, J.S.; Sam, D.L.; Vedder, P. (Eds.) Immigrant Youth in Cultural Transition: Acculturation, Identity and Adaptation Across national Contexts; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Georgas, J. Changing family values in Greece: From collectivism to individualism. J. Cross-Cult. Psyc. 1989, 20, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W.; Sabatier, C. Acculturation, discrimination, and adaptation among second generation immigrant youth in Montreal and Paris. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2010, 34, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W.; Phinney, J.S.; Sam, D.L.; Vedder, P. Immigrant youth Acculturation, identity and adaptation. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2006, 55, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmitz, P.; Schmitz, F. Correlates of acculturation strategues: Personality, coping and outcomes. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2022, 53, 875–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berry, J.W. Family and Youth Development: Some Concepts and Findings Linked to The Ecocultural and Acculturation Models. Societies 2022, 12, 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060181

Berry JW. Family and Youth Development: Some Concepts and Findings Linked to The Ecocultural and Acculturation Models. Societies. 2022; 12(6):181. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060181

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerry, John W. 2022. "Family and Youth Development: Some Concepts and Findings Linked to The Ecocultural and Acculturation Models" Societies 12, no. 6: 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060181

APA StyleBerry, J. W. (2022). Family and Youth Development: Some Concepts and Findings Linked to The Ecocultural and Acculturation Models. Societies, 12(6), 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060181