Let’s Play Democracy, Exploratory Analysis of Political Video Games

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Government and Ludic Experience

1.2. Videogames and Politics

1.3. Pandora’s Box: Online Multiplayer Video Games in Politics

2. Materials and Methods

- Separation of powers: independence of the executive, legislative, and judicial governments’ branches.

- Pluralism of political parties: electoral system that guarantees free and fair elections.

- Territorial decentralization: mutual limitation, delegating the administrative functions of the State.

- Guarantee of concrete freedoms: a system of protection of the rule of law, maintaining as precepts the basic freedoms of expression, conscience assembly, personal freedom, the right to property, equality, non-discrimination, the rights to life, education, work, culture, and health.

- Social justice: it has repercussions in compensating for the distribution of wealth, fairness of the judicial system and equality of opportunities.

- Serious games: provide learning to the player [60].

- -

- Persuasive games: convince the player about a position, idea or proposal, prescribing attitudes and provoking specific effects [61].

- -

- Expressive games: sensitize the player and create awareness by exploring cultural, social and psychological problems with the aim of creating empathy about a situation.

- Entertainment games: based exclusively on fun [61].

3. Results

3.1. Democratic Criteria in Video Games

- -

- Die Partei: political pluralism/social justice. The participation of three political parties that ideologically dispute the public spaces, in addition, the reflection of social justice is kept in evidence in the narrative when the law of the strongest is emphasized.

- -

- The Weimar Republic: political pluralism/guarantee of freedoms. Although it is a bipartisan dispute between only two ideological factions, it highlights the contrast of the strategies applied for the economic development of the Republic, delving into decision-making and variables to maintain the quality of life.

- -

- Femida: separation of powers/guarantee of liberties/social justice. Although the central axis is to propose the equitable distribution of justice, it also demonstrates the importance of freedom of expression and the separation of the powers of the State in the correspondence of exercising impartiality in the resolutions of the State.

- -

- Socratic Democracy: pluralism of political parties/social justice. Acting as a ruler in Greece, providing for the selection of different options that strengthen or diminish its popularity with the voters. It seeks to compete under the notion of bipartidism by balancing between decisions that generate acceptance among the different social levels.

- -

- Some Democracy Under Shower: separation of powers/social justice. During the dialogues of the video game, the characters express the preponderance of the division of powers to maintain the correct development of democracy. On the other hand, social justice is evidenced in the development of the gameplay through a metaphor about the equitable distribution of “water”.

- -

- God Bless Democracy: separation of powers/political pluralism/territorial decentralization/guarantee of freedoms. This is one of the most complete video games in this specific sample. Basically, it is about winning elections through slogans for California, North Texas, South Texas, Florida, New York, and the Lake Countries. To achieve this, the messages must be tailored to the characteristics of the voters.

- -

- Endless Democracy: political pluralism/guarantee of freedoms. It portrays the competitiveness of bipartisanship in terms of obtaining votes by controlling the sending of messages to potential voters subdivided into 8 groups. Freedom of choice is a condition for any democracy; therefore, the purpose of this experience is to keep the democratic game balanced for both political forces.

- -

- Time for Democracy: political pluralism/social justice. A videogame contextualized in Spain that seeks to understand the notion of political rotation in the government of the majority for the new generations symbolized through the fall of a dictatorship.

- -

- How to Rig an Election: separation of powers/guarantee of freedoms. The independence of the electoral power with respect to the executive power over the counting of votes is shown. On the other hand, the aim is to demonstrate the veracity of the postal voting by collecting them throughout the game, evading the police controls in charge of confiscating them.

- -

- Keep Everybody Happy: territorial decentralization/guarantee of freedoms. The aim is to harmonize the coexistence between 4 different groups, trying to improve their position, happiness and values by adapting them to their respective needs within the established environment.

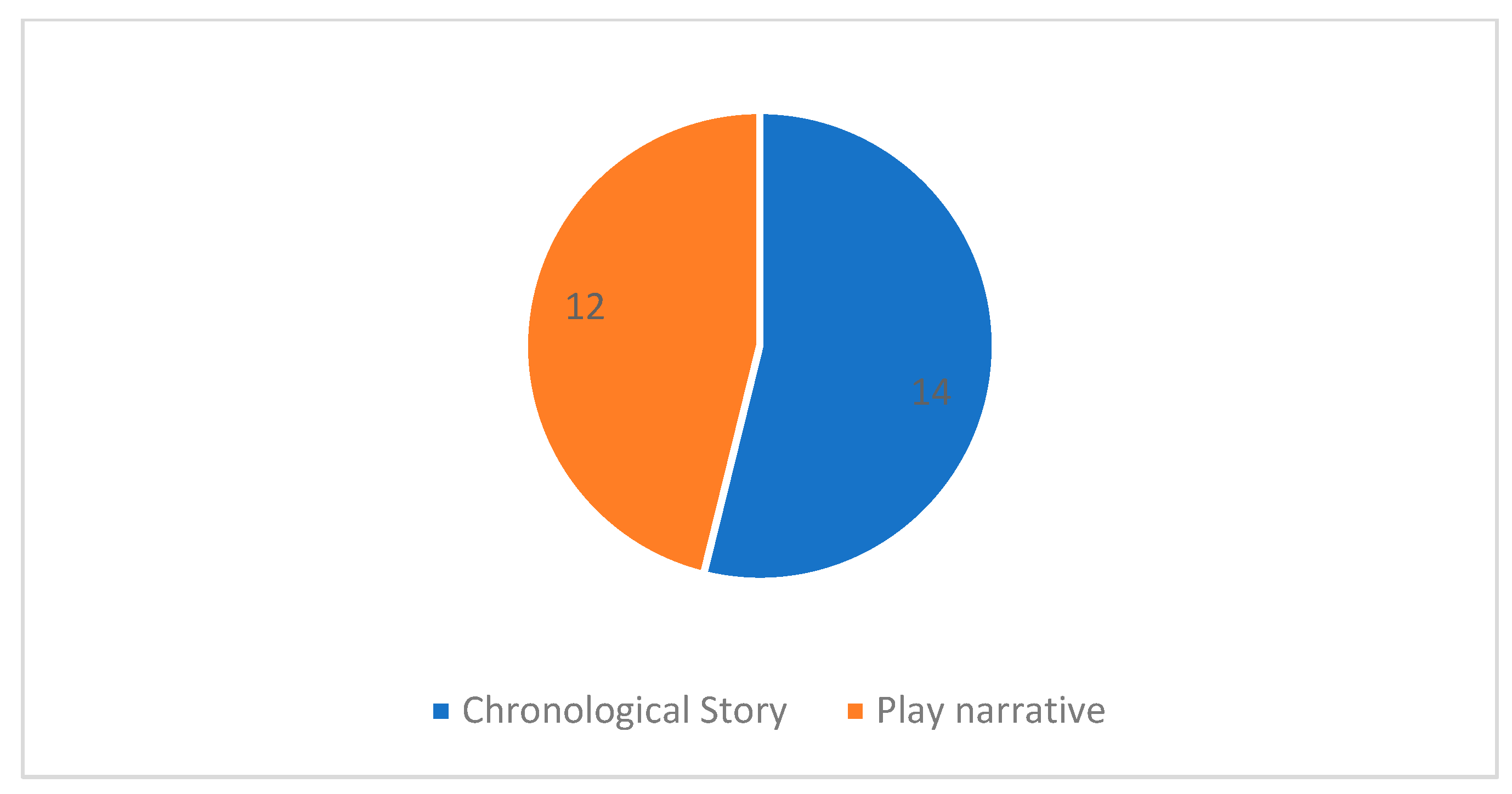

3.2. Typology of Democracy Video Games

3.3. Structure and Key Components of Democracy Video Game Design

3.3.1. Mechanics

3.3.2. Dynamics

3.3.3. Aesthetics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brinson, P.; ValaNejad, K. Subjective documentary: The cat and the coup. In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, Raleigh, NC, USA, 29 May–1 June 2012; pp. 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Azqueta, C. Características democráticas en videojuegos de simulación de gobierno. Obra Digit. 2022, 22, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, P. Gobernando el Vacío: La Banalización de la Democracia Occidental; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bogost, I. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames; MIT Press, EEUU: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, L.G.; Lmhoff, D.; Godoy, J.; Cena, M.; Ferreira, P. Videojuegos y socialización política: Evaluación del potencial de los videojuegos para promover aprendizajes sociopolíticos. Cuad. Cent. Estud. Diseño Y Comunicación. Ens. 2021, 130, 151–168. Available online: https://bit.ly/3i5Er2A (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Zamaróczy, N. Are We What We Play? Global Politics in Historical Strategy Computer Games. Int. St. Persps. 2017, 18, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrier, K. Designing role-playing video games for ethical thinking. Educ. Technol. Res. and Develop. 2016, 65, 831–868. Available online: https://bit.ly/3AyhKuD (accessed on 16 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Dishon, G.; Kafai, Y. Connected civic gaming: Rethinking the role of video games in civic education. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2019, 6, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraci, R.M.; Recine, N. Enlightening the galaxy: How players experience political philosophy in Star Wars: The Old Republic. Games Cult. 2014, 9, 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exmeyer, P.; Boden, D. The 8-Bit Bureaucrat: Can Video Games Teach Us About Administrative Ethics? Pub. Integrity 2020, 22, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfister, E.; Winnerling, T.; Zimmermann, F. Democracy Dies Playfully. Three Questions—Introductory Thoughts on the Papers Assembled and Beyond. Gamevironments 2020, 13, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, D. “eXplore, eXpand, eXploit, eXterminate”: Affective Writing of Postcolonial History and Education in Civilization V. G. Stud. 2016, 16, 409–424. Available online: https://bit.ly/3tP5kuE (accessed on 17 November 2022).

- Martínez, J.A.M. Mensajes políticos y derechos humanos en los videojuegos. Commun. Pap. 2021, 10, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planells, A. Mundos posibles, grupos de presión y opinión pública en el videojuego Tropico 4. Trípodos 2015, 37, 167–181. Available online: https://bit.ly/3EuRlyM (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Manin, B. Los Principios del Gobierno Representativo; Alianza Editorial: Spain, Madrid, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Puente, H.; Sequeiros, C. Goffman y los videojuegos: Una aproximación sociológica desde la perspectiva dramatúrgica a los dispositivos videolúdicos. Rev. Esp. Soc. 2019, 28, 289–304. Available online: https://bit.ly/3Ub5szn (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Mainer, B.; Martínez, C.; Puente, H. Videojuegos y Educación. Aprender a Través de Los Géneros Narrativos; Universidad Francisco de Vitoria: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hjorth, L. Games and Gaming (An Introduction to New Media); Berg, EEUU: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Vigilar y Castigar; Siglo XXI: Madrid, Spain, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Sequeiros Bruna, C.; Puente Bienvenido, H. Democracia, deslegitimación y cambio social: El videojuego como dispositivo de cuestionamiento político. Barataria, Rev. Cast.-Manch. Cien. Soc. 2020, 29, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín Gutiérrez, I.; Hinojosa Becerra, M.; Ruiz San Miguel, J. Newsgames en Ecuador. Correspond. Anál. 2018, 8, 121–145. Available online: https://bit.ly/3tIDmk0 (accessed on 18 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Positech Games. Democracy 3. Positech Games. 2013. Available online: https://bit.ly/3i154G3 (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Stardock. The Political Machine. Ubisoft. 2004. Available online: https://bit.ly/3hT1yNS (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Verlumino Studios. The Political Process. Early Access. Verlumino Studios. 2019. Available online: https://bit.ly/3i4b54X (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Akbar, F.; Kusumasari, B. Making public policy fun: How political aspects and policy issues are found in video games. Pol. Policy Futur. Educ. 2022, 20, 646–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L. Politics of fun and participatory censorship China’s reception of Animal Crossing: New Horizons. Convergence 2022, 13548565221117476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iNK Stories. 1979 Revolution: Black Friday. iNK Stories. 2016. Available online: https://bit.ly/3goRlZc (accessed on 13 November 2022).

- Rad, S.R. Politics of Language in Video Games: Identity and Representations of Iran. Int. J. Persian Lit. 2021, 6, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradox Interactive. Hearts of Iron. 2022. Available online: https://bit.ly/3gkZPRi (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Ubisoft Montreal. Assassin’s Creed III. Ubisoft. 2012. Available online: https://bit.ly/3UZBf7n (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Wills, J. “Ain’t the American Dream Grand”: Satirical play in Rockstar’s Grand theft auto V. Eur. J. Am. Stud. 2021, 16, 17274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKernan, B. Digital Texts and Moral Questions About Immigration: Papers, Please and the Capacity for a Video Game to Stimulate Sociopolitical Discussion. Games Cult. 2021, 16, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, J.; Hernández Pérez, J.F.; Khan, S.; Cano Gómez, A.P. Game Perspective-Taking Effects on Players’ Behavioral Intention, Attitudes, Subjective Norms, and Self-Efficacy to Help Immigrants: The Case of “Papers, Please”. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2018, 21, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxis Emeryville. SimCity. Electronic Arts. 2013. Available online: https://bit.ly/3EUnrWo (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- Limbic Entertainment. Tropico 6. Kalypso Media. 2019. Available online: https://bit.ly/2x0CDNj (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Playrix Entertainment. Township. 2011. Available online: https://bit.ly/3i2nbeK (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Firaxis Games. Civilization VI. 2016. Available online: https://bit.ly/3gsbMVe (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Paradox Development. Europa Universalis IV. Paradox Interactive. 2013. Available online: https://bit.ly/2MbvdNB (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- Paradox Development. Victoria II. Paradox Interactive. 2010. Available online: https://bit.ly/3XzkUIq (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Paradox. Crusader Kings III. 2020. Available online: https://bit.ly/3gsuxrq (accessed on 17 November 2022).

- Ensemble Studios. Age of Empires IV. 2017. Available online: https://bit.ly/3Vh7ZZv (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Blue Byte. Anno 1800. Ubisoft. 2019. Available online: https://bit.ly/3XoOSig (accessed on 19 November 2022).

- López Gómez, S.; Fernández Lanza, S. Video games to encourage participation and social commitment. Pedagog. Social. Rev. Interuniv. 2021, 39, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R. The Tearoom. 2017. Available online: https://bit.ly/3tODU7Q (accessed on 19 November 2022).

- Rahimabad, R.M.; Rezvani, M.H. Identifying Factors Affecting the Empathy of Players in Serious Games. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Serious Games Symposium, ISGS, Tehran, Iran, 25 November 2021; Volume 2021, pp. 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, S. “Liberty for Androids!”: Player choice, politics, and populism in detroit: Become human. Eur. J. Am. Stud. 2021, 16, 17360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawers, N.C.; Demetrious, K. All the animals are gone? The politics of contemporary hunter arcade games. Continuum 2010, 24, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, G.A.H. Videojuegos políticos: Una forma diferente de entender la política. Razón Y Palabra. 2007, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Neys, J.; Jansz, J. Political Internet games: Engaging an audience. Eur. J. Commun. 2010, 25, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-García, S.; Chicharro-Merayo, M.; Vicent-Ibáñez, M.; Durántez-Stolle, P. The politics that we play. Culture, videogames and political ludofiction on steam. Index Comun. 2022, 12, 277–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente, H.; Sequeiros, C. Poder y vigilancia en los videojuegos. Teknokultura 2014, 11, 405–423. Available online: https://bit.ly/3gndMxR (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Weihl, H. Dissonance, truth and the political limits of possibility in MMOs. J. Gaming Virtual Worlds 2014, 7, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IGG. Lords Mobile. 2016. Available online: https://bit.ly/3EwyFPl (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Hommadova Lu, A.; Carradini, S. Work–game balance: Work interference, social capital, and tactical play in a mobile massively multiplayer online real-time strategy game. New Media Soc. 2020, 22, 2257–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankoski, P.; Staffan, B. Game Research Methods: An Overview; ETC Press, EEUU: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, G.; Martínez, N.E.L. La observación, un método para el estudio de la realidad. Xihmai 2012, 7, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Iñiguez, E. La verdadera democracia: Las características indispensables. Rev. Estud. Políticos 2005, 127, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer-Carías, A.R. Democracia. Sus elementos y componentes esenciales y el control del poder. Nuria González Martín (Compil. ) Gd. Temas Para Obs. Elect. Ciudad. 2007, 1, 171–220. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, L.; Woldenberg, J. Principios y Valores de la Democracia; Instituto Federal Electoral: México City, México, 1997.

- Ratan, R.A.; Ritterfeld, U. Classifying serious games. In Serious Games; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Trépanier-Jobin, G. Differentiating serious, persuasive, and expressive games. Kinephanos April Spec. Issue 2016, 107–128. [Google Scholar]

- King, D.; Delfabbro, P.; Griffiths, M. Video game structural characteristics: A new psychological taxonomy. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2010, 8, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lope, R.P.; Medina-Medina, N. A comprehensive taxonomy for serious games. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2017, 55, 629–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amory, A. Game object model version II: A theoretical framework for educational game development. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2007, 55, 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walk, W.; Görlich, D.; Barrett, M. Design, dynamics, experience (DDE): An advancement of the MDA framework for game design. In Game Dynamics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hunicke, R.; Leblanc, M.G.; Zubek, R. MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research. In Proceedings of the Challenges in Games AI Workshop, Nineteenth National Conference of Artificial Intelligence, San Jose, CA, USA, 25–29 July 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Merchán-Romero, J.; Torres-Toukoumidis, A. Types of Gameplay in Newsgames. Case of Persuasive Messages about COVID-19. J. Media 2021, 2, 746–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, C.A. Theoretical coding in grounded theory methodology. Grounded Theory Rev. 2009, 8, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cheresky, I. El Nuevo Rostro de la Democracia; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, J.; Ridgway, J.; Weber, F. Educación estadística, democracia y empoderamiento de los ciudadanos. Rev. Paradig. 2021, 42, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil de Zúñiga, H.; Molyneux, L.; Zheng, P. Social media, political expression, and political participation: Panel analysis of lagged and concurrent relationships. J. Commun. 2014, 64, 612–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zackariasson, P.; Wilson, T.L. (Eds.) The Video Game Industry: Formation, Present State, and Future; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rodhan, N. The social contract 2.0: Big data and the need to guarantee privacy and civil liberties. Harvard Int. Rev. 2014, 16, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Yeates, N. Globalization and social policy: From global neoliberal hegemony to global political pluralism. Glob. Soc. Policy 2002, 2, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, E. The New Separation of Powers: A Theory for the Modern State; OUP: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, N. Videogames, persuasion and the War on Terror: Escaping or embedding the military—Entertainment complex? Political Stud. 2012, 60, 504–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genvo, S. Defining and Designing Expressive Games. J. Media Stud. Pop. Cult. 2016, 90–106. [Google Scholar]

| Gamejolt | ||

|---|---|---|

| N° | Title | Maker |

| 1 | The Democracy Times | Agar3s |

| 2 | BrazilianikMakia | Fayvit |

| 3 | Die Partei | AD1337 |

| 4 | Democracy Cat | Locatise |

| 5 | Venti Mesi | We are Muesli |

| 6 | The Weimar Republic | Africacrossgames |

| 7 | Ending Apartheid | Africacrossgames |

| 8 | Arrival of Democracy | Brikasoft |

| 9 | Slava Ukraini! | Africacrossgames |

| 10 | Femida | Loznevoy |

| 11 | Operation: Forklift | Technocrat |

| Itch.io | ||

| 12 | Save democracy in Greece | Gkrsss |

| 13 | Democracy Battle | WombatSpecialist |

| 14 | Socratic Democracy | Pedrorns |

| 15 | Some democracy under shower | Matote |

| 16 | Wave of Democracy | Arhpositive |

| 17 | God Bless Democracy | Barsweik |

| 18 | Your Cat lives in a Democracy | Jonathan Giroux |

| 19 | Endless Democracy | Alon Tzrafi |

| 20 | Time for Democracy | Guillem Serra |

| 21 | Tragedy of TV | GGHF |

| 22 | Little Fat Boy | Alambik |

| 23 | How to Rig and Election | Political Games |

| 24 | Pledge to a New Tomorrow | Fort Condor Productions |

| 25 | Keep Everybody Happy | Daniel Schulz |

| 26 | Beneath the Surface of Democracy | Cat in the Dark |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torres-Toukoumidis, A.; Gutiérrez, I.M.; Becerra, M.H.; León-Alberca, T.; Curiel, C.P. Let’s Play Democracy, Exploratory Analysis of Political Video Games. Societies 2023, 13, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13020028

Torres-Toukoumidis A, Gutiérrez IM, Becerra MH, León-Alberca T, Curiel CP. Let’s Play Democracy, Exploratory Analysis of Political Video Games. Societies. 2023; 13(2):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13020028

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorres-Toukoumidis, Angel, Isidro Marín Gutiérrez, Mónica Hinojosa Becerra, Tatiana León-Alberca, and Concha Pérez Curiel. 2023. "Let’s Play Democracy, Exploratory Analysis of Political Video Games" Societies 13, no. 2: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13020028

APA StyleTorres-Toukoumidis, A., Gutiérrez, I. M., Becerra, M. H., León-Alberca, T., & Curiel, C. P. (2023). Let’s Play Democracy, Exploratory Analysis of Political Video Games. Societies, 13(2), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13020028