Teaching the Greek Language in Multicultural Classrooms Using English as a Lingua Franca: Teachers’ Perceptions, Attitudes, and Practices

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Migration in the European and the Greek Context

2.2. The Role of L1 in Teaching Students with a Refugee/Migrant Background

2.3. The English Language

3. Methodology

- What are teachers’ perceptions and attitudes toward the use of ELF in teaching L2 Greek in this context?

- What are teachers’ reported practices regarding the use of ELF to teach L2 Greek in multicultural classrooms in formal primary education in Greece?

3.1. Participants

3.2. Data Collection Methods

4. Findings

4.1. Questionnaire Findings Regarding Teachers’ Perceptions and Attitudes

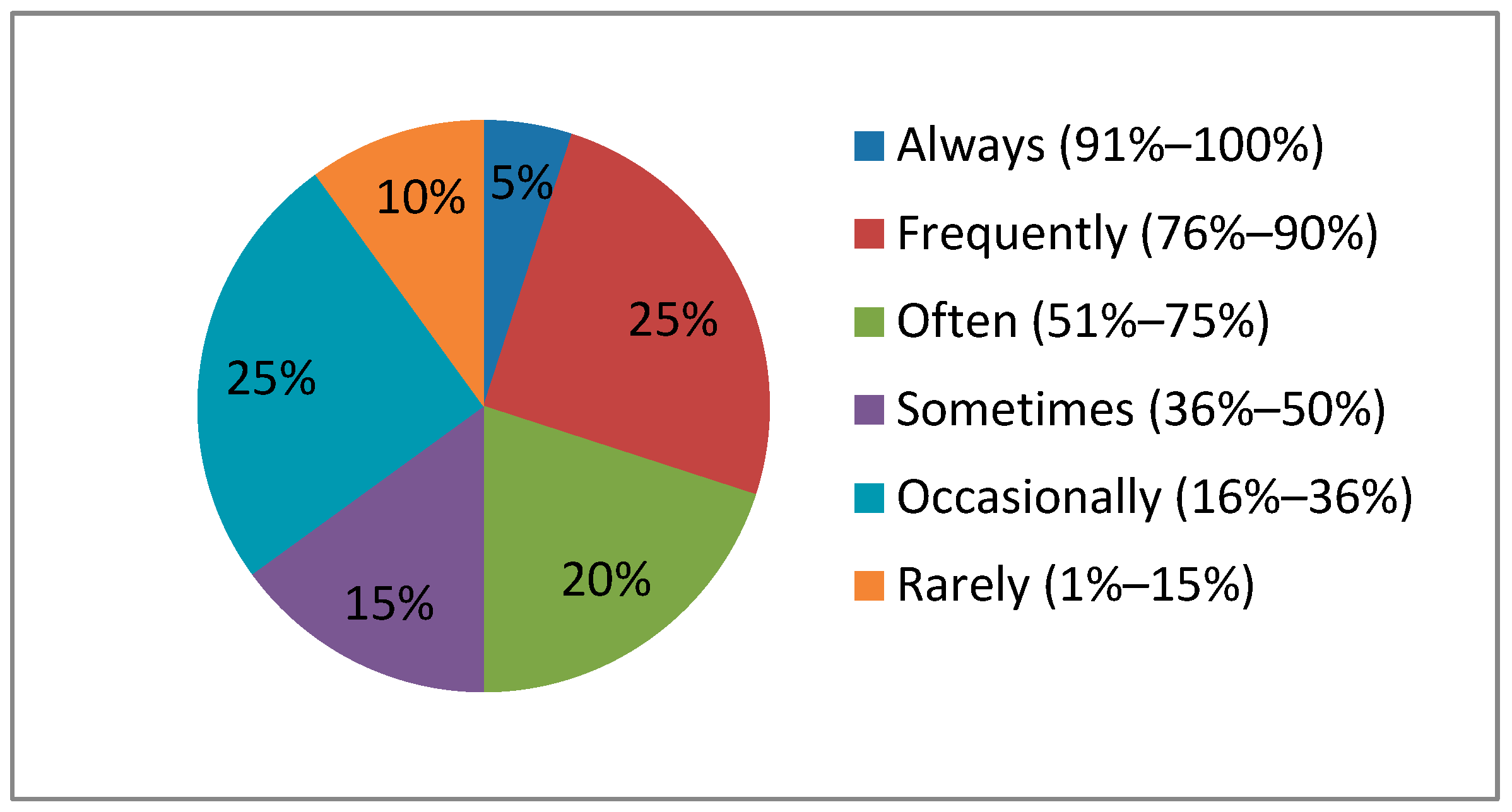

4.2. Questionnaire Findings Regarding Teachers’ Practices

4.3. Written Accounts Findings Regarding Teachers’ Practices

Sometimes I translate difficult words like ‘revolution’ or ‘slavery’ in order to make them understand historical events or the contexts.(T1)

A typical example in one of the last lessons was related to the order of the words in the sentence (subject-verb-object). A student of mine who started learning Greek in October (8 years old) has difficulty in understanding this word order in simple sentences and I told her to have in mind the very simple and useful sentence ‘I LOVE YOU’. The same happens in Greek; the subject usually enters first, then the verb, and finally the object.(T4)

One example that I remember was during the Carnival. I was explaining this day to my students and a boy from Syria mentioned the word ‘Halloween’. Based on that reference, we continued the discussion with more students and they mentioned words [in English] like costumes, pumpkins, and spiders.(T7)

4.4. Metaphor Elicitation Findings

4.5. Interview Findings Regarding Teachers’ Perceptions and Attitudes

It definitely makes it easier and I feel better, otherwise there could be no lesson. I don’t speak Russian; they don’t speak Greek at a good level, so there could not be a lesson. Therefore, English is very useful and, as I see it, the children are happy with English as they seem to understand. Otherwise, they would not understand.(T1)

Yes, of course, they feel more secure. They feel that they can confront this difficult situation. Sometimes they make connections directly between the English and the Greek language.(T4)

They are proud of it. They keep telling me that they are good at using English and they feel happy.(T2)

They are happy because they see it [speaking English] as a game.(T5)

It helps but not in learning Greek terminology but in communication. […] It helps a lot in some cases in which students already speak English well.(T7)

Interrupting the lesson to explain something to five students in English interrupts the flow of the lesson and this is time consuming.(T4)

4.6. Interview Findings Regarding Teachers’ Practices

These children come to school without speaking Greek. Therefore, the first approach is always in English, but unfortunately, many children do not understand this language. […] I am talking specifically about refugees because it is very difficult to communicate with them. For example, I learned some Russian to communicate with the immigrants from the Soviet Union. On the contrary, I cannot do the same with the refugees because they speak too many different languages and dialects. In these cases, English is the key to communicate with them, with the refugees.(T2)

If I want to explain something, I will say the word or the phrase first in English and then I will translate these phrases into Greek. For example, when I want to teach children about food, I will say this word in English ‘Food’ so as to be sure that my learners understand the meaning. I also use simpler vocabulary that is frequently used. For example: ‘let’s go’. Therefore, I translate vocabulary, especially during my students’ first days at school.(T5)

We very often use the English language to teach Greek but it is also useful in history. For example, when I want to teach the tenses in Greek, during the history lesson I sometimes use the past tenses of English in order to make them understand this grammatical phenomenon.(T4)

We also use English to raise phonological awareness. When I try to teach them the sound/d/in Greek, I tell them the word ‘dog’ and they understand the phonological rules.(T2)

5. Discussion

5.1. ELF as a Facilitator and Promoter of Self-Confidence and Inclusion

5.2. Teachers’ Reported Practices Involving ELF

5.3. Pedagogical Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferguson, G. The Practice of ELF. J. Engl. A Ling. Fr. 2012, 1, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifakis, N.C.; Fay, R. Integrating an ELF pedagogy in a changing world: The case of Greek state schooling. In Latest Trends in ELF Research; Archibald, A., Cogo, A., Jenkins, J., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars: London, UK, 2011; pp. 285–298. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, J. Repositioning English and Multilingualism in English as a Lingua Franca. Englishes Pract. 2015, 2, 49–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kostoulas, A. Ιδεολογικοί μηχανισμοί προτυποποίησης στα διδακτικά εγχειρίδια αγγλικής γλώσσας [Ideological standardisation processes in ELT coursebooks]. In Ιδεολογίες, γλωσσική επικοινωνία και εκπαίδευση [Ideologies, Linguistic Communication and Education]; Motsiou, E.V., Gana, E., Kostoulas, A., Eds.; Gutenberg: Athens, Greece, 2021; pp. 162–189. [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira, S. Critical perspectives of Brazilian teachers on English as a lingua franca. In Social Justice, Decoloniality, and Southern Epistemologies within Language Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nunan, D. The impact of English as a global language on educational policies and practices in the Asia-Pacific region. In Learner-Centered English Language Education; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 164–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mol, C.; De Valk, H. Migration and immigrants in Europe: A historical and demographic perspective. In Integration Processes and Policies in Europe; Garcés-Mascareñas, B., Penninx, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham Switzerland, 2016; pp. 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNHCR. Situation Mediterranean Situation. 2023. Available online: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Sakellis, Y.; Spyropoulou, N.; Ziomas, D. The Refugee Crisis in Greece in the Aftermath of the 20 March 2016 EU-Turkey Agreement; European Social Policy Network: Brussels, Belgium, 2016; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. Greece Factsheet—September 2021 [EN/EL]—Greece. 2021. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/greece/unhcr-greece-factsheet-september-2021-enel (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Atkinson, D. The Mother Tongue in the Classroom: A Neglected Resource? ELT J. 1987, 41, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, V. Using the First Language in the Classroom. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 2001, 57, 402–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. L1 Use in L2 Vocabulary Learning: Facilitator or Barrier. Int. Educ. Stud. 2008, 1, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, B. The Use of English as a Lingua Franca in the Japanese Second Language Classroom. J. Engl. A Ling. Fr. 2018, 7, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J. Intercultural Education and Academic Achievement: A Framework for School-Based Policies in Multilingual Schools. Intercult. Educ. 2015, 26, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O.; Kleyn, T. Translanguaging with Multilingual Students: Learning from Classroom Moments; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hornberger, N.H. The Continua of Biliteracy and the Bilingual Educator: Educational Linguistics in Practice. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2004, 7, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eurydice Report. In Integrating Students from Migrant Backgrounds into Schools in Europe: National Policies and Measure; Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA), Education and Youth Policy Analysis, Cop: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Manoli, P.; Mouti, A.; Kantzou, V. Children with a Refugee and Migrant Background in the Greek Formal Education: A Study of Language Support Classes. Multiling. Acad. J. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2021, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mattheoudakis, M.; Chatzidaki, A.; Maligkoudi, C. Greek teachers’ views on linguistic and cultural diversity. Sel. Pap. ISTAL 2017, 22, 358–371. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. The Most Spoken Languages Worldwide in 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/266808/the-most-spoken-languages-worldwide/#statisticContainer (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Kachru, B.B.; Nelson, C.L. World Englishes. In Sociolinguistics and Language Education; McKay, S., Hornberger, N., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; pp. 71–102. [Google Scholar]

- Kachru, B.B. World Englishes and Culture Wars; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ife, A. A role for English as Lingua Franca in the foreign language classroom? In Intercultural Language Use and Language Learning; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Antón, M.; DiCamilla, F. Socio-Cognitive Functions of L1 Collaborative Interaction in the L2 Classroom. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 1998, 54, 314–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantzou, V.; Vasileiadi, D.M. On Using Languages Other Than the Target One in L2 Adult Language Education: Teachers’ Views and Practices in Modern Greek Classrooms. J. Lang. Educ. 2021, 7, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R. The Study of Second Language Acquisition; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Grounded Theory in Global Perspective. Qual. Inq. 2014, 20, 1074–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R.; Barkhuizen, G. Analyzing Learner Language; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kramsch, C. Metaphor and the subjective construction of beliefs. In Beliefs about SLA: New Research Approaches; Kalaja, P., Barcelos, A.M.F., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaja, P.; Barcelos, A.M.; Aro, M.; Ruohotie-Lyhty, M. Beliefs, Agency and Identity in Foreign Language Learning and Teaching; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D. The use of English as a lingua franca in teaching Chinese as a foreign language: A case study of native Chinese teachers in Beijing. In Language Alternation, Language Choice and Language Encounter in International Tertiary Education; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 161–177. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, T. English as a Multilingua Franca and ‘Trans-’ Theories. Englishes Pract. 2022, 5, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, H. The role of native language in the teaching of the FL grammar. J. Educ. 2012, 1, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ulug, M.; Ozden, M.S.; Eryilmaz, A. The Effects of Teachers’ Attitudes on Students’ Personality and Performance. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 30, 738–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Positive Stance of the Use of English | |

|---|---|

| Using English in My Class Is… | |

| Metaphors | Explanation |

| a lifesaver | because it helps me teach anything easier and faster |

| an ice cream | because my students love it and always want it |

| a bridge | because it helps communication in many cases when they lack the linguistic skills in Greek |

| a godsend | because it helps students in moments when they reach a dead end in the learning process |

| a key | because with it I can unlock any comprehension hindrance |

| a mystery game | because English is the key to solve the mystery |

| a helper | because we use it as a common language of communication |

| traveling abroad using a dictionary | because it helps me communicate with people from different places |

| a tool to communicate | because students might come from different countries, therefore English is fairer to them |

| Negative Stance of the Use of English | |

|---|---|

| Using English in My Class Is… | |

| Metaphors | Explanation |

| a disaster | because my students are not familiar with English |

| the open sea | because Greek and English function in a very different way and this doesn’t help my kids to guide themselves around and understand how Greek should work |

| the tower of Babel | because everyone speaks its own language |

| Neutral Stance of the Use of English | |

|---|---|

| Using English in My Class Is… | |

| Metaphors | Explanation |

| a role-play | because students have a different attitude when they speak |

| a common secret | because everybody knows it |

| a necessary evil | because it helps a lot with difficult concepts but it slows the learning process |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giannakou, A.; Karalia, K. Teaching the Greek Language in Multicultural Classrooms Using English as a Lingua Franca: Teachers’ Perceptions, Attitudes, and Practices. Societies 2023, 13, 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13080180

Giannakou A, Karalia K. Teaching the Greek Language in Multicultural Classrooms Using English as a Lingua Franca: Teachers’ Perceptions, Attitudes, and Practices. Societies. 2023; 13(8):180. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13080180

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiannakou, Aretousa, and Kyriaki Karalia. 2023. "Teaching the Greek Language in Multicultural Classrooms Using English as a Lingua Franca: Teachers’ Perceptions, Attitudes, and Practices" Societies 13, no. 8: 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13080180