Abstract

Aimed at understanding how pastoralist livelihoods are affected within the Northwest Region of Cameroon, this article explores the nexus of social justice, indigenous know-how, livelihoods, social security, and sustainability through a political ecology lens. Through a qualitative case study based on in-depth interviews with 59 key informants, this study departs from existing literature by exploring the linkages that exacerbate risks and vulnerabilities for pastoralist livelihoods. We situate the contending issues through emerging data and analysis, which highlight indigenous elements that sustain pastoralist livelihoods (coping strategies and sustenance) and identify diversified barriers that impede pastoralists’ sense of social justice and community-mindedness. Other intersecting pointers identified relate to environmental interactions, social security, sustainability, and decision-making within local and national governance mechanisms that either enhance or impede sustainable development. We proposed a social justice ecosystem framework (SJEF) that uncovers the enmeshments of social justice, social security, indigenous know-how, and livelihoods, with implications for sustainable development. The framework makes a compelling case for co-produced policies; implementing symbiotic social justice-based policies is mandatory, encapsulating thriving aspects of pastoralists’ unique traditions, which are often missed by governments and agencies in social community development planning and sustainable development initiatives.

Keywords:

social justice; pastoralists; livelihoods; indigenous; political ecology; ecosystem; gender; sustainability 1. Introduction

Developing-country households face an increasingly challenging set of shocks including economic, political, and health inequalities, which present multiple threats to livelihoods and well-being [1,2,3]. These risks have been exacerbated by climate change in recent decades, with enormous implications for food security and agrarian livelihoods [4]. In Africa, climate change is having direct impacts on agriculture and food security, as well as on the economy. The Sahel region and Horn of Africa are particularly affected by a combination of different shocks and risks. By 2030, up to 118 million people will be exposed to drought, floods, and extreme heat, hindering progress in alleviating poverty [5].

Pastoralists are people for whom livestock rearing is their primary economic and livelihood activity; however, the future viability of pastoral livelihoods poses great challenges for achieving many of the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [6]. In pastoral societies, herders are mobile with livestock, targeting the patchy availability of grazing areas, while other household members remain sedentary for parts of the year [7]. Pastoralists deploy a myriad of livelihood strategies within their social and ecological contexts to cope with risks and vulnerabilities. However, socio-economic factors, such as changes in land tenure, agriculture, and sedentary activities, lead to fragmentation of pastoral systems [8]. The challenge is to ensure policies improve household livelihoods [9], with livelihood diversification being crucial for stabilizing household income [10]. A 2021 UN report highlights widespread knowledge gaps and detrimental policies that exacerbate livelihood problems in pastoralist systems [11]. As Smith and Frankenberger [2] opine, there is a growing need to strengthen the evidence base for interventions and programming approaches that bolster households’ resilience to shocks. That is the focus of this study, which seeks to gain insights into the social justice systems of pastoralist communities in Cameroon’s Northwest Region.

With 23.4 million pastoralists in the Horn of Africa, 14.8 percent of the region’s population relies on pastoralism [5,11,12] which is threatened by climate change [13]. These climatic events cause large-scale displacements of people, contributing to national and subregional instability and poverty. Higher levels of displacement and food insecurity exacerbate volatility and reverse the progress made in socio-economic development over the past decade [5].

SDG 1.3 calls for governments to ‘implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all’. Achieving the SDGs entails building social justice and security in marginalized, poverty-stricken, and under-resourced communities. Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want, outlined a socio-economic transformation of Africa within 50 years; the Abidjan Declaration-Advancing Social Justice: Shaping the future of work in Africa, adopted by ILO [12], calls for extending sustainable social protection coverage progressively [1,2,3]. However, there is a deficit in policy around understanding social justice and livelihood shocks—a key component of poverty reduction strategies [5,11,14]. Only 17.4 percent of the population in Africa are recipients of at least one social protection benefit; accelerating coverage remains a very high priority [12]. Therefore, embedding social justice-based policies [15] and extending social protection in these particularly fragile contexts warrants strengthening institutions [5,12].

Owing to the importance of livestock systems for sustaining rural livelihoods, there is a clear need for empirical, micro-level analyses of the processes by which pastoral communities understand and use coping or adaptation pathways in response to these effects. This study aligns with the FAO’s [16] conceptualization of pastoralism as a livelihood activity in which pastoralists derive income and sustenance, primarily from cattle rearing and other agricultural activities, subject to unpredictable climate change events and incidents. From this definition, we surmise that social justice issues are central to pastoralist livelihood strategies. Therefore, mapping differential aspects of vulnerability and formulating a social justice framework to cater to these livelihood shocks in ambulant pastoralist communities cannot be ignored [1].

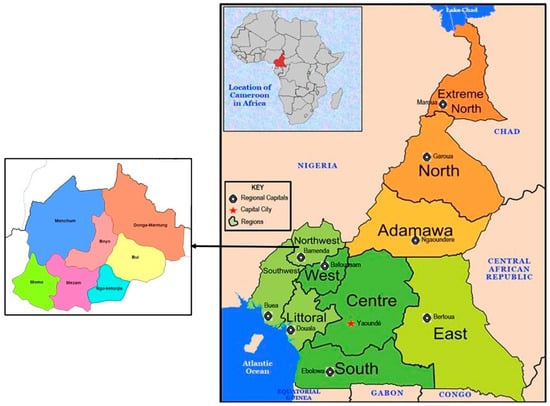

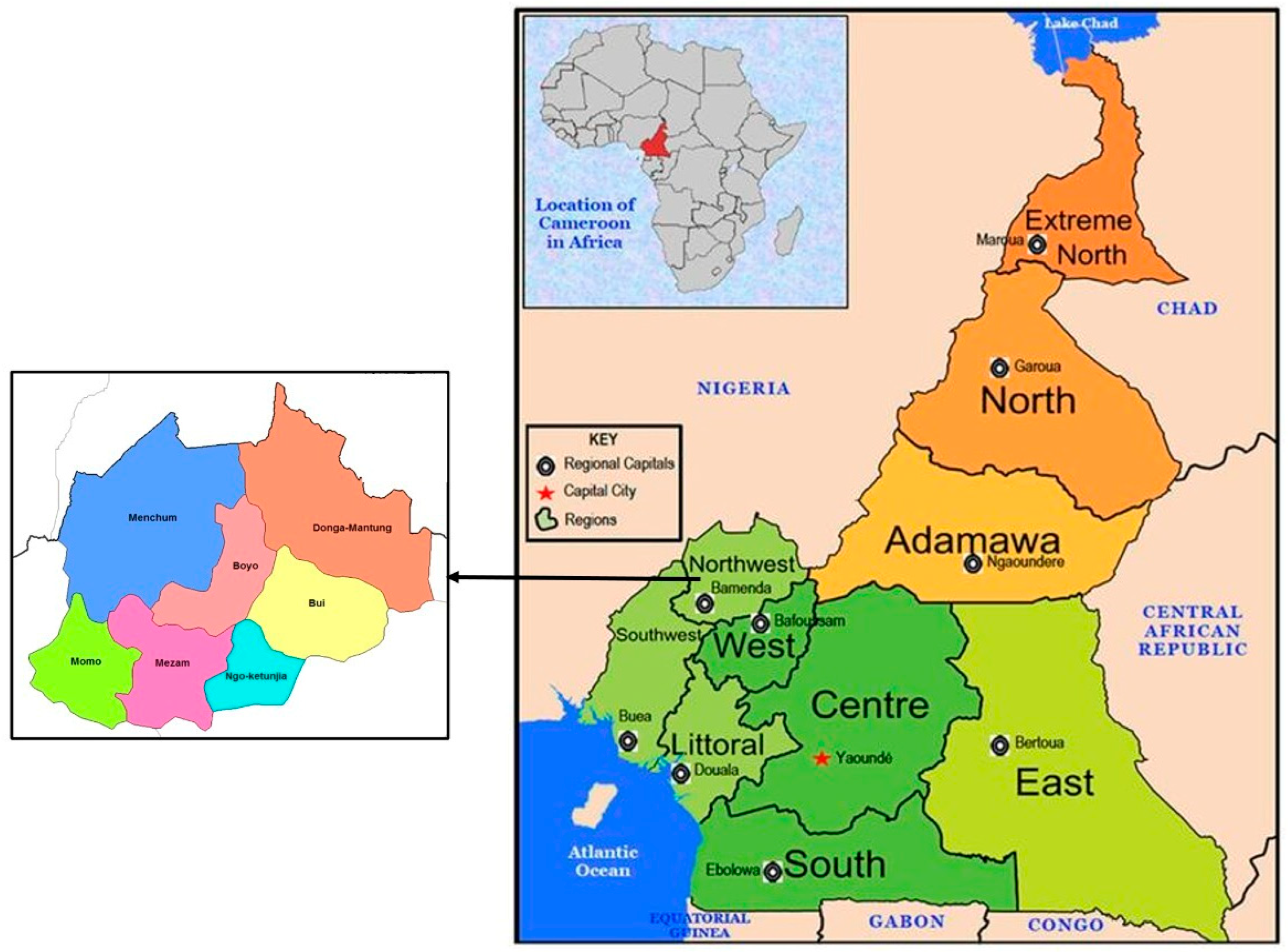

Focusing on pastoralists in Cameroon’s Northwest Region (Figure 1), this study aimed to assess how social justice and sustainable development initiatives enable or hinder pastoralists’ livelihoods. The study’s objectives are firstly, to explore how social justice and pastoralist livelihoods are regimented through indigenous know-how. Secondly, to discern the conditions for social justice/security and coping strategies affecting pastoralist livelihoods. Thirdly, to uncover the implications of political ecology (human-–environment nexus and governance decisions) on pastoralist livelihoods; and lastly, we envision the proposal of a social justice ecosystem framework based on empirical data and theoretical analysis.

A major problem impeding the effectiveness of social justice and social security has been the importation of ‘Western’ social protection programs, without considering their relevance to the local demographic’s social, cultural, and economic needs [17]. Through the prism of political ecology, we explore literature and policy on pastoralist livelihoods, challenges, and opportunities. The implementation of policies to enhance social justice through empowering poor farmers, pastoralists, and the landless [3] is crucial. Such policies provide guidance to relevant stakeholders, to help them better understand how pastoralists can be supported.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 1 presents the introduction, background context, and study objectives. Section 2 provides a snapshot and details of Fulani pastoralists—a brief history, placement, numerosity, customary habits, social structure, and livelihood strategies, including a map of the study area. Section 3 explicates the theoretical framework of the paper and focuses on literature related to social justice, political ecology, and indigenous knowledge. Section 4 provides an overview of the research methodology, including the data collection process and fieldwork in Northwest Cameroon. Section 5 presents the findings and results based on interview insights regarding livelihood strategies and challenges faced by pastoralists. Section 6 synthesizes the emerging findings and presents the proposed social justice ecosystem framework—a nexus of social justice, indigenous know-how, livelihoods, social security, and sustainability from a political ecology lens. Section 7 presents the discussion, informed by the field data and emerging policy perspectives. Finally, Section 8 provides a conclusion and pathways for sustainable development.

2. Pastoralism in Cameroon and Context of the Study

Cameroon is a lower–middle-income country located on the coast of Central Africa (Figure 1); the total population is expected to reach 50 million by 2050 [18]. According to the Ministry of Livestock, Fisheries, and Animal Industries [19], there are approximately six million cattle in Cameroon, distributed over the mountainous northwest region, the Adamawa plateau, and the Northern regions of Cameroon. With over 1.5 million inhabitants, Cameroon’s Northwest Region (the case study of this research) is home to approximately 100,000 Fulani pastoralists [20].

Figure 1.

Map of Cameroon showing the northwest region and study area. Adapted from [21].

Figure 1.

Map of Cameroon showing the northwest region and study area. Adapted from [21].

In Cameroon, Fulani pastoralists constitute about 12% of Cameroon’s population of over 25 million people, and there are approximately six million cattle in Cameroon, distributed over the mountainous northwest region, the Adamawa plateau, and the Northern regions of Cameroon [19]. These pastoralists navigate grazing sites predominantly used for subsistence agriculture, putting them on a collision course with farmers. Clashes between pastoralists and host communities aggravate the vulnerability and sustainability of livelihoods, exacerbating the already weak social security systems in pastoralist communities. Hence, the relevance of our study lies in advocating for a social justice framework that targets communities battling with social protection and sustainable livelihoods [3], highlighting the pressing need for a paradigm shift in pastoralism science and policy [22], as corroborated through a review of related literature.

With livestock (cattle rearing) as a significant livelihood activity, the Fulani pastoralists of the Western Highlands of Cameroon are a subgroup of the Fulbe, a wider pastoral group whose members are dispersed across sub-Saharan Africa. They migrated and settled in the northwest region in the early twentieth century at different times, in migratory waves. Since arriving in the region, they have experienced different stages of transformation due to changing socio-economic, political, and ecological conditions, which have influenced their nomadic lifestyle and ambulant activities spread across geographical areas of the region (Figure 1). In terms of customary habits, social structure, and livelihood strategies, Fulani pastoralists have moved from a purely nomadic lifestyle that involved cattle rearing as a permanent placement, to seasonal migration with cattle herds and families, and then to a semi-nomadic lifestyle, involving forward and backward movements to previous settlements at the end of each transhumance season. Recently, Fulani pastoralists have adopted a more sedentary community lifestyle, with seasonal movement of herders and cattle during dry periods [3].

The ongoing conflict in the anglophone regions has ravaged communities and disrupted livelihoods [23,24], with mechanisms of service provision and social justice increasingly fragmented [8]. The case of pastoralist communities is notable, warranting an investigation, hence the basis of this research. Historical accounts link the Lamidat of Sabga (established in 1905), a precursor to herder settlements in the region [25]. Since then, the growing number of drylands has rendered pastoralists vulnerable, exacerbated by protracted herder–farmer conflicts and reduced access to grazing land in Northwest Cameroon [26]. In search of pasture for their cattle, pastoralists navigate grazing sites where subsistence agriculture is predominant, thereby putting them on a collision course with farmers. Indeed, Fulani pastoralists in the region are susceptible to recurrent skirmishes with neighboring farming communities.

Over the years, social groups/associations have emerged within the pastoralist communities to resolve livelihood-related socio-economic challenges. Amongst them is the Mbororo Social, Cultural, and Development Association (MBOSCUDA)—an umbrella organization in pastoralist communities created to scale up social justice and sustainable development by deploying Pulaaku—a cultural repertoire of value systems, social norms, and traditions.

We argue that social justice issues are central to pastoralist livelihood strategies in the Northwest Region of Cameroon. Enhancing pastoral resilience hinges on buffering the social justice systems, which can enable Cameroon to reverse progress made in socio-economic development over the past decade. Therefore, this article takes the social justice debate further, often omitted in the literature on farmer–herder conflicts in Africa. As Manzano et al. [22] recently noted, the need for a paradigm shift in pastoralism science and policy is pressing. The social justice angle is the pursuit of this study.

3. Theoretical Framing: Insights from Political Ecology and Indigenous Knowledge

Political ecology theory is shaped by concerns for justice within marginalized groups [27]. Issues such as resource challenges, poverty and inequality, local context, and the uneven distribution of livelihoods are prominent [28]. Equally important is how indigenous communities cope with a set of broader political–economic processes [29]. Harrill [30] (p. 670), for example, characterizes political ecology as an inquiry into “the causes and consequences of environmental change to facilitate sustainable development through the reconstruction of social and political systems”. From a political ecology standpoint, the emphasis is on “the importance of complex dynamic interactions into the study of relationships between human society, the ecological web and the physical environment” as “neither politics nor the environment operates as a dependent or an independent variable; they are interdependent” [31] (p. 372).

Within this study, political ecology enables a response to fluctuating livelihoods and how social justice is shaped in terms of power relations between pastoralists and a nexus of socio-environmental conditions they confront, with implications on sustainability. A political ecology perspective offers a valuable lens as it exposes the nexus of social justice, inequality, poverty, and power in reproducing ecosystems and systemic economic inequalities [32].

Indigenous knowledge encompasses a broad set of practices passed down through generations, guiding communities’ daily interactions with the natural world. These practices may be old and traditional or may include innovations [33,34]. To move away from pigeonholing knowledge, understanding indigenous knowledge presents a counter perspective to often hegemonic, Western views of development and sustainability. Schech [35] stressed the importance of including ethnicity, history, gender inequality, culture, and indigenous knowledge in development initiatives. Indigenous knowledge-based practices are envisioned as a roadway to a secure future led by environmental justice [36]. In this direction, Chilisa [37] argued for the decolonization of social research in non-Western developing countries. This study aims to present the particularities of livelihoods inherent within pastoralist communities through an envisioned framework based on indigenous approaches to social justice and social security.

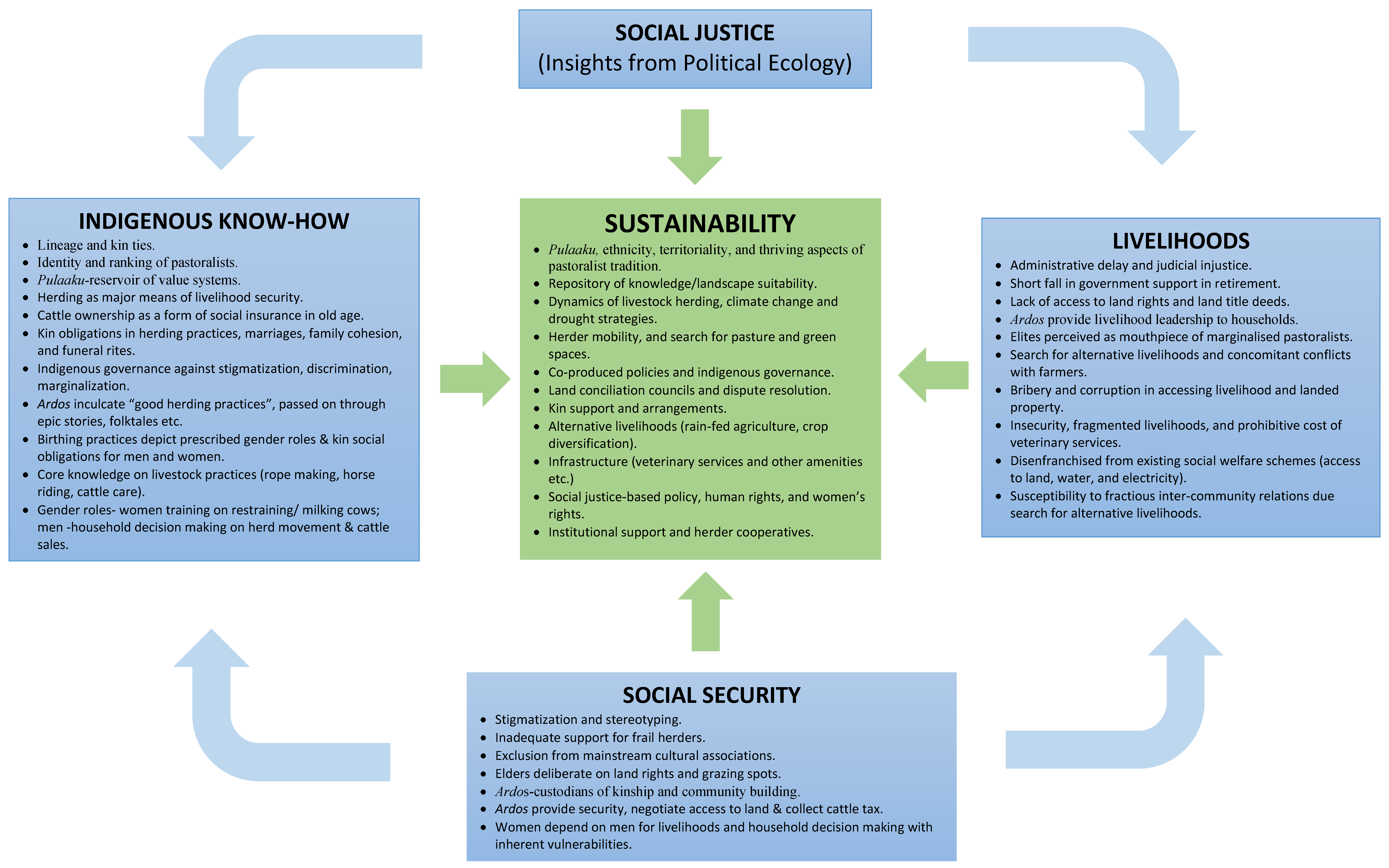

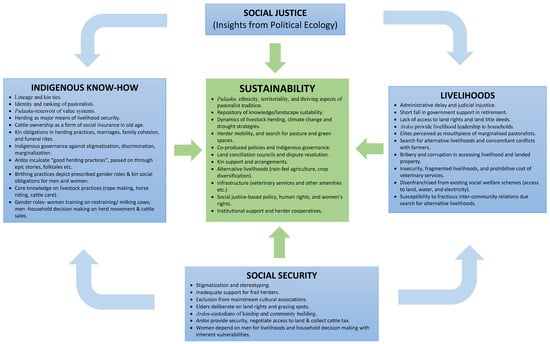

Notably, political ecology is perceived as an approach to investigating human–environment relationships that problematize the economic and political processes affecting access to, and use of, land and resources [38]. Blaikie’s work on political ecology demonstrated the nexus between environmental knowledge and the mutual dependency of social values. As an analytical lens for understanding and explaining environmental change and its impact on people, Blaikie’s political–ecological insights are relevant to this paper, from the political imperative and desire to rectify social injustices within communities [39]. Blaikie [27] posited that political ecology offers a paradigmatic shift from the structural to a more interactionist way of understanding society and the environment where aspects of group dynamics, position in political economy, source of power, interest and aims, the means to reach aims, and issues of exclusion and marginalization require careful consideration. The underpinning argument is that ecological change cannot be understood without linking the economic and political institutions/structures within which it is embedded. With a solid political imperative and desire to correct social injustices, we follow through these paradigm shifts in the SJEF (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Envisioned social justice ecosystem framework (SJEF) for enhancing livelihoods and sustainability. Source: Authors (developed from empirical data and insights from political ecology).

Blaikie’s [40] (p. 208) conceptualization of a political ecology for developing countries and the typology of hunter–cultivators as focal points of interest resonate with this article. There is a strong connection between how policy and environmental discourse can be used to address challenges facing socially vulnerable populations [39]. We argue that Blaikie’s pragmatic co-production of environmental knowledge and social values provides a viable means of building socially just environmental policy applicable to pastoralist communities in this research. Fundamentally, political ecology theory offers a valuable lens to understand the nexus of social justice, social security, and sustainable development within the context of persistent farmer–herder conflicts in Northwest Cameroon [26]. The role of Indigenous know-how in seeking solutions and capacity building warrants further investigation.

Governments in the global South have missed opportunities to integrate indigenous systems with statutory, formal state provisions [17], creating a spiral of disadvantage for pastoralists, undermining social justice and sustainable development. Through the lens of social justice, insights into indigenous know-how can be acquired on the need for local communities to formalize ‘social rights’. That is the case in many African traditions that have integrated indigenous know-how into their social justice systems via village-led institutions and traditional governance [15]. In addition, feminist political ecology offers insights into how power and other structural factors impact environmental issues and human–environment interactions [41]. Within this study, this perspective provides a valuable entry point to understand ways of addressing structural inequalities, particularly land ownership, and use of natural resources, critical in addressing gendered vulnerabilities as part of a process of gender-transformative change [42], imperative for sustainable development in pastoralist communities.

In ascertaining the connection between indigenous know-how, social justice, and their implications for social policy and practice, we argue that gendered livelihood strategies, as espoused in Table 1 below, are central to conceptualizing social justice within pastoralist communities based on contextual realities. As Chambers [43] advocated, such realities entail respecting people’s realities and listening to their views and priorities to improve livelihoods. Arguably, the enduring value of community agency in African traditions is centered around a social justice framework that enhances social development outcomes. Essentially, this study examines community-based social justice/security, where indigenous know-how is undeniably central to pastoralist livelihoods.

Table 1.

Gendered livelihood strategies in pastoralist community.

Social Justice and Sustainable Development in Pastoralist Communities

Though there is no consensus on a definition of social justice, the core principles of equity, fair access to services, and equality of opportunity are central to this study. Within the context of pastoralist–farmer interactions, Devereux [44] (p. 9) conceptualizes social justice as: “social equity to protect people against social risks such as discrimination and abuse”. The European Report [3] on Social Protection for Inclusive Development advocated for inclusion efforts that enhance the capability of the marginalized to access social insurance and assistance—both components of social security coverage. Thus, social justice systems and protection programs will be required to mitigate chronic poverty and reduce vulnerability [5,12,14]. Embedding social justice-based policies and extending social protection in these particularly fragile contexts warrants strengthening institutions [12,15].

Sustainable Development Goal 1.3 calls for governments to “implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all”. Achieving the sustainable development goals (SDGs) entails building social justice and social security in marginal, poverty-stricken, and under-resourced communities. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed stark gaps, notably among workers in the informal economy [12], including pastoralist communities of Northwest Cameroon, where social justice mechanisms remain problematic. Hence, the AU calls for advancing social justice in all communities [45] and progressively extending sustainable social protection coverage [5,11,12].

Similarly, there is a deficit in policy around understanding social justice and livelihood shocks—a key component of poverty reduction strategies [11,14,46]. A social justice agenda to guarantee human rights, provide income security through livelihood strategies, ensure affordable access to essential services, and other support for marginalized groups such as older adults and persons with disabilities, with the primary aim of alleviating poverty and exclusion remains conflated [11,12]. In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), social security provisions premised on formal, state-organized systems cover only small segments of citizens [17,45]. This falls short of the minimum requirements espoused by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 3.1). Given the limited coverage, the role of social protection as a sustainable development strategy is now widely recognized as a universal approach to achieving SDGs [12,47].

Aspects of vulnerability and formulating a social justice framework to cater to livelihood shocks in ambulant pastoralist communities cannot be ignored [1]. Sabates-Wheeler [48] argues that understanding rights is a determinant of social protection, particularly for forcibly displaced populations. Extending social security coverage is now widely recognized as an effective human rights and policy issue, as it addresses extreme deprivation and vulnerability in marginalized communities [5]. The notion of social justice revolves around human rights, inclusion, and addressing the discrimination that affects social protection for marginalized groups [49], including pastoralists. Indigenous safety nets and informal social security mechanisms, which are often instrumental in mitigating the negative impacts of shocks in pastoralist enclaves, are rudimentary and outside the scope of state administrative mechanisms.

In guaranteeing old age security, pastoralists rely on social and family networks–kinship-based systems and other agencies based on the principles of solidarity and reciprocity [15,17]. However, development policy has yet to respond sufficiently from a social justice lens in challenging forms of inequality, promoting the right to participation and self-determination based on developing strengths [50]. A significant problem impeding the effectiveness of social justice and social security has been the importation of ‘Western’ social protection programs without consideration of their relevance to local demographic, social, cultural, and economic needs [17]. From a human rights perspective, a reframed social justice agenda should uphold and promote well-being and dignity, recognizing inner strengths, distributing resources, and challenging unjust policies and practices [15,50].

4. Methodology

This study adopted a qualitative research methodology, informed by a case study and inquiry-based approach grounded in empirical evidence gathered from semi-structured interviews conducted in the Northwest Region of Cameroon (Figure 1). In-depth interviews were conducted between October and November 2022, with the aid of research assistants, involving 59 participants and key informants. In this exploratory study, we interviewed 59 informants (n = 59) through purposive sampling deemed appropriate, which covered the broad spectrum of the community and institutions operating within the region. Out of the total number of 59 informants, there were different subgroups with forty-one (n = 41) being Fulani pastoralists aged 35 to over 50 years, seven (n = 7) were female members of pastoralist households, six (n = 6) were community leaders and elders in charge of pastoralist governance structures, three (n = 3) were local administrative officials representing ministries of agriculture, livestock and animal husbandry, rural and community development, and two (n = 2) were officials from the pastoralists cultural and development association (MBOSCUDA). Participants were drawn from rural pastoralists’ enclaves of Sabga, Jakiri, and Wum—significant localities of the northwest region and cattle grazing hubs. We obtained ethical approval from relevant local authorities, and individual consent and approval were sought from participants and informants through a consent form and participant information sheet, with an explanation of the research process, permitting informants to opt in or out of the research.

A purposive sample represented the most appropriate method of reaching pastoralist groups spread throughout the northwest region. Purposive sampling enables the “selection of participants or sources of data to be used in a study, based on their anticipated richness and relevance of information concerning the study’s research questions” [51] (p. 311). The sampling strategy was contextually appropriate, covering the spatial administrative units and diverse grazing sites. The sample represents an opposite reflection of pastoralist community layers of power and kin dynamics. The female interviewees were recruited with the assistance of Ardo (Fulani/pastoralist leader), owing to the regulated kin regime in place. Semi-structured interviews enable data to be collected rigorously and methodically while allowing the interviewer to modify the sequence or wording of questions where necessary [52].

A purposive sample enabled the researchers to focus on designated enclaves, using open-ended questions to explore the social dynamics and assess the viability of social justice, informal social security, and kinship arrangements primarily driven by pastoralists themselves. Given the variations in living patterns among Fulani pastoralists, purposive sampling was suitable for capturing diverse perspectives from dispersed pastoralist settlements. By focusing on a target population and specific group, the researchers were able to generalize results that can be replicated and informed by the desired information sought [52].

Semi-structured interviews and case study approaches align with the rigor of small case studies, grounded in case study logic. This technique can yield more reliable data for in-depth, interview-based studies [53]. Small [54] avers that case studies do not only generate theory but also somehow speak to empirical conditions in other cases not observed. The challenge is to make these cases contextually relevant, allowing respondents to freely express their experiences, which are captured in direct quotations. In a case study, sampling applies to selecting cases and data sources “that best help us understand the case” [55] (p. 56). The case is made that ethnographic researchers facing today’s cross-methods discourse and critiques should adopt alternative epistemological assumptions better suited to their unique questions, rather than retreating to models designed for statistical research [54]. Given the diversity of pastoral systems, the questions were framed to explore the sustainability of mutual support arrangements within the communes and how pastoralists cope and adapt to social changes.

Viewpoints from the data generated were authenticated and triangulated with community members and other participants from the sampled locations. The MBOSCUDA officials interviewed provided insight into existing partnerships with other agencies. The MBOSCUDA served as a focal point for the initial engagement of research participants and pathways into the community. There were no conflicts of interest as the research process was explained, consent was agreed upon, and confidentiality was assured with selected interviewees.

English, Pidgin English, and the local Fulani dialect were used as mediums of expression to gather information, and a translator was used when the informant opted to speak in the local dialect. Interviews were tape-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed in conjunction with the research questions and aims of the study. To shed light on ‘invisible aspects’ in pastoralist communities, the translator helped administer the semi-structured interviews and other observations. The questions and themes explored centered around livelihood implications from indigenous practices and structures, gender and livelihood strategies, challenges, ecological factors affecting pastoralists’ livelihoods, the setup of social justice, social security, and implications for sustainability, in tandem with decision-making (external and internal) affecting pastoralist livelihoods. Qualitative data were analyzed thematically, in line with emerging themes related to the study’s aims (see Table 2).

A limitation of the study was the possibility of accurate information lost in translation services; however, this was mitigated through further authentication of interview transcripts with other vital participants and officials of MBOSCUDA.

5. Findings and Results

Based on the aims of the study and research questions, emerging themes gleaned from the interviews are presented here and triangulated with existing literature. In analyzing the results, we used (n = ) to represent the total number of informants, and the various subgroups as highlighted in the methodology. Indigenous institutions and practices such as the Pulaaku and Ardo (Fulani leader) connected with social justice in pastoralist communities, gendered livelihood strategies, challenges of implanting social justice, social security, and the implications on livelihoods and sustainable development are x-rayed.

5.1. Traditional Governance and Kin Arrangements in Pastoralist Communities

The two MBOSCUDA participants (n = 2 subgroup) and five community elders (n = 6 subgroup) in charge of pastoralist governance structures highlighted that the Pulakuu represents a cultural repertoire of value systems, social norms, and traditions central to traditional/local administration and social justice in pastoralist communities. Further inquiries revealed that the Pulaaku is negotiated through kin reciprocity, which hinges on culture and the template for pastoralists’ herding practices to regulate customary and social relations. Eight respondents (n = 2 and n = 6 subgroups) mentioned that the code sanctions good animal husbandry, communal obligations, and a ‘social obligation contract’. Furthermore, the research gathered that the pulaaku has four tenets: munyal (fortitude in adversity and ability to accept misfortune), hakkilo (sound common sense and manners), semteende (reserve and modesty in personal relations) and neddaaku (dignity) (MBOSCUDA official, informant). For pastoralists, pulaaku conveys uniqueness and difference; it dictates kin norms regarding dignity, social resilience, humility, endurance, secrecy, and communal solidarity [8,9,26].

Similar findings indicate that the pulaaku helps maintain an ethnic boundary around the Fulani category [26]. Identity consciousness remains an ideology of racial and cultural distinctiveness and superiority that uniquely ranks pastoralists from other ethnic groups [56]. From our findings, we deduce that Fulani herders equate their pastoral way of life to ethnicity and heritage, which implicitly enforces lineage bonds. A pastoralist (n = 41 subgroup) stated: “We can only retain lineage social bonds through our kindred social ties. Pastoralists marry within pastoralist groups, often with ‘close relatives’, to preserve pulaaku and herds”.

Most informants (n = 46) agreed that preserving the pulaaku is primordial in kin arrangements; an MBOSCUDA Official (n = 2 subgroup) stated: ‘Other ethnic groups see Fulani as uneducated, primitive ‘aku’ people, whilst the Fulani look down on the natives in rural areas as haabe, meaning people who are poor’.

5.2. Indigenous Know-How in Pastoralist Communities

Fifty-seven informants (n = 57) affirmed that indigenous know-how in pastoralist communities is implemented through the Ardorate (apex of local administration under the tutelage of the Fulani leader). The interviewees (n = 46) perceived the Ardorate as the ‘social justice powerhouse’ in pastoralist communities. They clarified that the Ardos at the helm of the Ardorate are respected pastoralists charged with dispensing social justice. Ardos operate within the Ardorate and provide guided leadership in micro enclaves between households and broader power structures of the Lamido—superior title holder responsible for tax collection and fostering relations with the state.

This finding aligns with that of Mbih et al. [57], who ascertained that Ardos are custodians of kinship and pillars in community building and fostering inter-community relations with other ethnic groups and farming communities. Usually, the Ardorate comprises a group of grazing families from the same lineage. The Ardo’s authority principally relates to cattle rather than territory. In line with kin support, the significant duties of Ardos (primarily elders) include the protection of subjects’ interests, negotiating with local chiefs and administrative authorities for access to land, and collecting cattle tax (jangali) from herders within the Ardorate. Other secondary data sources reveal that pastoralists perceive their minority status as a protected characteristic reinforcing the notion of contested citizenship [58]. The analysis of interview transcripts indicates that Ardos regulate the political economy and foster social bonds, enhanced through indigenous structures of kin governance (n = 36).

Similar indigenous structures exist in other African countries. Akin to the Ardorate is the council of elders of grazing associations in Kenya (jaarsa mata dedha), saddled with political, social, and decision-making functions in synergy with the government [50]. Similarly, the Afar herders of Ethiopia cope with the severity of drought through customary and clan elders who meet, whenever necessary, and communicate policies, evaluate, and decide when to allow access to preserved grazing areas [59].

Further inquiries revealed that kin obligations follow a structured pattern, with Ardos managing herding practices, legitimating marriages, family cohesion, child upbringing, deaths, and funeral rites. Most of the respondents (n = 49) asserted that since cattle is a lifeblood in livelihoods, Ardos inculcated good herding practices taught in Fulani schools and passed on through epic stories, folktales, and songs. Whilst kin arrangements conjure a sense of common ancestry, its traditional resilience is tested, as intimated in subsequent sections.

5.3. Pastoralists Livelihood Strategies

Caring for livestock is central to social justice and kin social security obligations. A participant (Ardo-Fulani chief, n = 6 subgroup) affirmed: ‘Mbororos are proud of their tradition; cattle are everything to us. The lineage earns a livelihood from cattle. Cattle confers respect with both men and women guarding the herds.’ Herds are integral to pastoralists and a significant means of livelihood security [59], enabling pastoralists to address livelihood challenges.

Our research found that social justice is implemented in pastoralist communities through kinfolks participating in livelihood task descriptors. A critical analysis of the interview transcripts sieved gendered livelihood strategies from the respondents as shown in Table 1.

Critically, our analysis shows that the task descriptors could be blurred depending on settlement patterns. Apart from child-rearing and guaranteeing food security, social justice is leveled up through gendered strategies for men and women to sustain the lineage. An informant (n = 7 subgroup) recounted:

“Women left home to reside with their parents before their first delivery and stayed over for at least one to two years after delivery. These women learned how to use herbs. During the naming ceremony, the baby’s head was shaved after being soaked in a bowl of milk, and a sheep was slaughtered”.

These intrinsic birthing practices point to prescribed gender roles and kin social obligations for women [60]. Practically, in all African pastoral communities, women play the traditional role of livestock rearing, processing milk, selling dairy products, and maintaining households. Yet, they do not own valuable property, are the least educated, and are excluded from decision-making processes, resource management, and allocation [5,14].

We contend that implementing social justice mechanisms is central to pastoral livelihoods. Through social justice mechanisms such as community social events, core knowledge of livestock practices and smallholder farming are shared. Indeed, pastoral communities rely on systems of indigenous knowledge of rangeland management to make decisions that influence livelihoods [61]. Some informants (n = 26) conveyed that herders are trained in cattle grazing and other skills such as rope making, horse riding, and cattle care. Female livelihood skills include preparing dairy products such as milk, cheese, butter, and snacks. A female (n = 7 subgroup) stated: “We build girls’ skills on how to milk cows and restrain calves when extracting milk. We also demonstrate domestic tasks such as cooking, cleaning and fetching water to ensure stable households when pastoralists are on the move”.

Similarly, amongst the Samburu of Kenya, a patrilineal society, livestock inheritance primarily entails the transfer of livestock from fathers to sons, thus ensuring that property stays in the lineage. At many points during life, livestock is bartered: at birth, initiation to warriorhood, before marriage, and finally, upon the father’s death. Women are caregivers for livestock that their sons ultimately inherit [60].

5.4. Pastoralists Livelihood Challenges

Based on information voiced by the participants, a constellation of challenges was listed as undermining pastoralist livelihoods. The main challenges identified were limited access to land (n = 51), continuous search for fertile green spaces and pasture (n = 55), regular clashes with farming groups when livelihood activities crisscross (n = 42), shrinking water resources (n = 26), drought and dry environment increasing the journey time to look for pasture (n = 29), corrupt nature in arbitration of herder–farmer conflicts (n = 17), suspicion and lack of respect from farming communities (n = 11), limited state social security provision (n = 19), risk of cattle theft (n = 35), and poverty (n = 57) made worse by raging conflict in the region (n = 51).

These vulnerabilities, that exacerbate pastoralists’ susceptibility to fractious inter-community relations, align with their lifestyle. Due to declining green pastures, some cattle owners move beyond pastoralist settlements to seek pasture. When resources are exhausted elsewhere, they seek new grazing opportunities, adding to demographic pressures on land, with perennial farmer–herder problems forcing herders out of ‘permanent’ settlements. Exacerbated by ever-shrinking pasture and water resources, this often led to farmer–herder skirmishes, which threatened traditional livelihoods due to growing pressures on land and recurrent droughts.

Research evidence elsewhere suggests that climate variability has also forced pastoralists to relocate from traditional grazing lands [62]. As conceptualized by Chambers [44], vulnerability has two sides: an external side of risks, shocks, and stress to which an individual or household is subject (climate variability in this context), and an internal side, which is defenselessness, meaning a lack of means to cope with damaging loss. Livelihood changes occur among pastoralists, but the most prevalent are diversification into agriculture and intensification of livestock production. As access to land remains contentious, pastoralists with larger herds engage in food production, putting them on a collision course with local farming communities [42]. An interviewee (n = 41 subgroup) said: “Our biggest problem stems from neighboring farmers due to tensions about cattle trespass and destruction of food crops. We struggle to find grazing areas. This insecurity weakens our chances of securing income”.

This finding is not unique to this study, as incidents of crop damage by pastoral animals are escalating into violent conflicts between herders and farmers [62]. In most cases, pastoralists pay veterinary professionals with little or no support from the government due to false beliefs of pastoralists as wealthy citizens. A female informant (n = 7 subgroup) was worried about declining income from dairy farming: “Our trade is plunging due to frequent conflicts with crop farmers. Though cattle are our lifeline, we need to find suitable markets, which means additional movement to urban areas to sell our dairy products”.

These livelihood challenges articulated by the respondents are worsened by the endemic conflicts in the northwest region, which have seriously damaged the region’s economy [23] and continue to disrupt markets with implications for sustainable livelihoods [24]. Furthermore, ethnic tensions are triggering conflicts with neighboring farming communities that affect livelihoods. Ethnicity remains a crucial marker of marginalization for pastoralists [54], as they endure spatial isolation and political marginalization in many African countries [5]. A worsening sense of vulnerability is evident, as one pastoralist (n = 41 subgroup) put it:

“Grazing lands are constantly threatened; we now travel longer distances to search for pasture. Also, there are many cattle diseases, and we need frequent intervention from veterinary technicians, which is costly”. On gaining access to land via legal means, an interviewee intimated: “Even when we go to Court to present our case, we do not get justice as we are always seen as occupiers with no land rights and deeds”.

To mitigate the livelihood challenges, senior elders often meet and discuss the migration of livestock, protection of the community from raids, and stresses induced by droughts. In bolstering support for pastoralists, an MBOSCUDA leader (n = 2 subgroup) explained: “Pastoralists are largely stigmatized and could benefit from literacy programs. In communities where projects are undertaken, women and young men could benefit from literacy programs and micro-credit schemes”.

These interconnected factors and social perceptions compound the fragility within pastoralist enclaves, exacerbated by protracted farmer–herder conflicts. These factors threaten the viability of kin social justice arrangements. The recurrent conflicts take a heavy toll on pastoralism in the Horn of Africa, engendering volatility of social security [14,45]. Such conflicts have resulted in deaths and the destruction of cattle and food crops, heightening the dislocation of livelihoods and the rural economy.

We argue that the co-production of solutions with local farming communities is vital in ensuring pastoral livelihoods due to variability in dryland farming systems. As GIZ [1] (p. 16) notes, embracing the diversity of existing sedentary and mobile farming systems and reflecting and strengthening their interactions is essential. Furthermore, literacy programs and other micro-credit schemes would empower and build on the capability of pastoralists to develop indigenous solutions. Additionally, donor organizations like DFID UK and Village AID UK could conduct baseline research, aligning development aid with livelihood needs identified by pastoralists.

5.5. Environmental Impact and Sustainable Development Initiatives

All interviewees (n=59) voiced concerns that environmental threats posed by climate change are significant obstacles to sustainable development initiatives. From a political ecology and social justice lens, we argue that the pressure from land use and transhumance activity where farmers safeguard cultivable land, and pastoralists search for pasture triggers herder–farmer conflicts. These pressures impact pastoralist livelihoods, making them vulnerable to varied environmental impacts. As highlighted in the literature [5,9], livestock is a fundamental form of pastoral capital and wealth with implications for sustainability and resilience when susceptible to varied weather and climatic conditions. As most interviewees (n = 41) noted, soil degradation leading to reduced pasture growth for cattle has been causing spilling effects: “We go a long way to find pasture. Also, we must arrange for veterinary care; the forward and backward movements create conflicts with crop farmers”. From the quotations and voices of participants, it is surmised that environmental pressures on grazing land affect pastoral social networks, reciprocal rights, and obligations [8].

We deduce from the findings that mobility is central to livelihood strategies in pastoralist communities, with cattle movement in vast areas that experience different landscapes and environmental conditions. Therefore, knowledge of the different grazing areas is essential. Consequently, herders’ knowledge and landscape suitability repositories are disseminated through folklores, fostering interactions between their livestock and the environment. Oba [61] describes incantations and songs of bravery, survival, and resilience deemed a form of social insurance, which are bequeathed to the lineage. The cattle folklore describes livestock watering, grazing movements, and coping with environmental stress [63].

The findings also show that the capacity to recover after droughts, climate variability, and change remains a challenge to resilience in pastoralist communities. Commenting on limited assistance despite the environmental impacts on their livelihoods, an informant (n = 41 subgroup) said: “Our cattle remain our history, identity, social security, culture and mode of subsistence, yet we do not get much support from the state”. Addressing vulnerability to droughts and other shocks to promote capacity is a significant concern for pastoral settlements in the dry lands of SSA [8,47].

As outlined above, expanding income opportunities is crucial to reducing shocks to pastoral livelihoods. Activities threatening the resilience of pastoral systems have been documented, including land loss from neighboring agriculturalists’ encroachment [9]. The loss of crucial resources, especially of dry season grazing areas and watering points, poses a considerable challenge to pastoralism [57].

Without the certainty of staying long in an area that pastoralists find temporarily suitable for grazing, an informant (n = 41 subgroup) stated: “We live in fear of being chased away from our land. Though we pay cattle tax (jangali), we have no electricity or water. Cattle is our sole way of survival”. Other concerns include the difficulties of accessing essential social services. Healthcare facilities are essentially out of reach for a clear majority in sedentary settlements, though semi-ambulant pastoralists live in enclaves with limited access to electricity and running water.

5.6. Social Justice and Sustainability

The dominant perception of social justice gleaned from the informants relies on a sense of community relations and building safety nets to minimize the impacts of social change. A female pastoralist (n = 7 subgroup) stated how pastoralists are wary of the knock-on effects of social change:

“We depend on men for livelihoods; if men are affected by a drop-in cattle activity and movements further from the homestead, then these uncertainties transfer unto women; we feel the pain too as social bonds are broken and financial insecurity looms as we rely on sales of milk, cheese, butter, and other dairy products to add to household income”.

Empirical evidence suggests that pastoralists feel disenfranchised from existing social welfare schemes in neighboring farming communities. Land contestations between pastoralists and crop farmers continue to engender tensions between these space partners. A respondent (n = 41 subgroup) highlighted the difficulty of having justice in court cases concerning their livelihood activity:

“Even when we go to Court to present our case, we do not get justice; we are seen as occupiers with no land rights and deeds…The lingering court sessions impact our kin support as the lineage is taken off normal herding practices to show up as witnesses in lengthy court proceedings”.

A similar study revealed that the protracted dissonance and delaying tactics deployed by administrative authorities through fruitless commissions of inquiry have not helped redress farmer herder conflicts [26].

Regarding long-term livelihood security, an informant (n = 41 subgroup) stated:

“We have limited government support in old age. Most of our children do not have public service jobs. Though we pay taxes, we do not have access to water, health centers, electricity, and veterinary services.’ On social security, he stated: ‘Providing old age protection is a problem. Frail herders are unable to walk for long distances in search of green pasture, so their livelihood is threatened. In addition, diseases affect our cattle, we are looked down upon as ‘strangers’ and ‘foreigners’ regarding land, and access to veterinary services is costly”.

A related issue of human rights emerged from the findings: A respondent (n = 41 subgroup) said: ‘We have no land rights as we are classed as intruders, foreigners. It is even worse as administrative authorities, through inspection fees dupe us.’ Additionally, the shoddy delivery of critical services, not helped by tenuous access to land, exacerbates tensions and strains with pastoralists’ kin arrangements. Kindred and kin protection is a vital form of old-age social insurance. Pastoralists consider kinship to be a ‘lifeline’ in preserving the identity of heritage. A pastoralist (n = 41 subgroup) noted: “Through our heritage support system, we can fight against stigmatization, discrimination, marginalization, exploitation, and oppression, impacting on us through land conflicts and evictions”.

The evidence suggests that due to the challenges of social justice and insecurity plaguing pastoralists, they are trying to access social services through unorthodox means. An informant (n = 41 subgroup) expressed this view: “Local people accuse us of offering bribes to administrative officials. We feel exploited as we give money and get empty promises in return”. Concerned with livelihood diversification that may bring uncertainty and insecurity, a female pastoralist stated: “Our men are looking to move away from cattle; it is now expensive to care for animals. When things go wrong through cattle diseases, we feel ‘strangled”.

Another social justice/security dimension emerged from interviews: buffering kin arrangements can guarantee social justice. A MBOSCUDA official (n = 2 subgroup) articulated this view: “Our interaction with other neighboring farming communities means we must maintain peaceful co-existence. We can learn from the model of Njangi (rotating credit and saving associations), a notable activity of pooling finances, which can improve credit allocation for younger pastoralists”.

Participants’ concerns echoed above resonate with Midgley [17], who contends that though governments are still the primary sponsors of social protection in the Global South, there are limited rates of social insurance coverage, inadequate funding, and administrative challenges impeded by a shortfall in social investments. External interventions and other institutions strongly affect pastoralists’ livelihood strategies [10], warranting a rethink of social justice-based policy options. Furthermore, Midgley [17] posited that formal security schemes serve the needs of workers in regular employment but ignore those earning a living in informal and subsistence agricultural sectors, akin to pastoralist livelihoods.

To mitigate these social justice and sustainability risks, we believe that realizing the human rights of mobile pastoralists to social security requires political will and good intentions. Pastoralists can achieve such rights through national legal institutions and regional and international legal regimes. In addition, targeted social safety net programs, addressing social changes and other factors creating vulnerability, will be needed to mitigate long-term shocks.

5.7. Pastoralist Livelihoods and Decision-Making

There is evidence of pastoralist involvement in livelihood decision-making in various ways, such as bribing the authorities. A pastoralist (n = 41 subgroup) noted: “We are wrongly perceived by farming communities as wealthy and influential, so they feel we can manipulate administrative authorities, but we are left out of government schemes”. Also, pastoralists are susceptible to political marginalization by their leaders; a respondent held: “We have elite pastoralists who are the perceived mouthpiece of marginalized pastoralists; however, these elite exploit us for their political gain”.

Furthermore, the research found that some Ardos feel relegated from mainstream activities of MBOSCUDA, considering their significant role in grassroots mobilization. Younger pastoralists feel alienated from externally driven projects, as echoed by a pastoralist (n = 41 subgroup): “Most external projects focus more on cattle, and there is no thought around how our livelihoods are impacted and the changes we need to make”.

Insights into the findings prove that familial arrangements depict a structure of decision-making. At household levels, the male family head oversees cattle ownership. Household roles within ‘compounds’ (larger households) are distributed per gender and age. Older men are responsible for all aspects of decision-making and activities regarding movement, health, and sale of cattle. Spouses of the family head have ‘milking rights’ and not the authority to sell cattle. Respect for elders is entrenched in kin reciprocity, which resonates with prevalent forms of informal social security. Apart from the Ardos, other community leaders (Nyako) are revered. An interviewee (n = 7 subgroup) stated: “Younger herders pay huge respect to a Nyako. They are required to assist with basic needs like fetching water, washing, dispatching messages, and looking after herds of cattle as directed by the Nyako”.

Besides the Nyako (most senior), the Ndotijo (family head) are esteemed for their duty of care to the lineage. According to Oba [61], such a status is noticeable amongst the Matheniko indigenous institutions of Ethiopia, where decision-making is the prerogative of the elders–senior age set (kathiko). These tensions undermine kin support and resilience with implications for inclusiveness in decision-making. Akin to South Africa, Matthews [64] applies a human rights perspective to conceptualizing and implementing the national social protection system as it interacts with labor policy. Focusing on the concept of non-discrimination, Mathew points to gendered and racial discrimination in the labor market, which perpetuates the exclusion of Black South African women from accessing social protection.

6. Social Justice Ecosystem Framework (SJEF)

Figure 2 is the proposed SJEF that synthesizes the key findings through social justice as the overarching theme, informed by political ecology theory. The other key themes are indigenous know-how, livelihoods, and social security, with sustainability at the center. The peripheral themes are interconnected, and all relate/link back towards sustainability, which is at the framework’s core and aligned with the research objectives.

Table 2.

Research objectives, emergent themes, and a summary of the emerging findings gleaned from the participants (n = 59).

Table 2.

Research objectives, emergent themes, and a summary of the emerging findings gleaned from the participants (n = 59).

| Research Objectives | Emergent Themes | Summary of Emerging Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Explore how social justice and Pastoralist livelihoods are regimented through Indigenous know-how | Indigenous Know-how | The pulaaku is a cultural repertoire of value systems, social norms and traditions central to traditional/local administration and social justice in pastoralist communities. |

| The pulaaku has four tenets: fortitude in adversity and ability to accept misfortune, sound common sense and manners, reserve and modesty in personal relations and dignity. | ||

| For pastoralists, pulaaku dictates kin norms regarding dignity, social resilience, humility, endurance, secrecy, and communal solidarity. | ||

| The pulaaku helps in defining a sense of identity, ethnicity, and territoriality. | ||

| Herders equate their pastoral way of life to the heritage, which implicitly enforces lineage bonds. | ||

| Identity consciousness helps to uniquely separate out pastoralists from other ethnic groups. | ||

| Pastoralists retain lineage social bonds through kindred social ties through intra marriages. | ||

| While other ethnic groups view herders as uneducated & primitive, herders consider other ethnic groups, especially in rural areas as poverty-stricken. | ||

| Indigenous Governance | Ardos work within the Ardorate and provide guided leadership in micro enclaves, located between households. | |

| Ardos are custodians of kinship, and pillars in community building and fostering inter-communal relations. | ||

| The Ardo’s authority includes protecting land rights, negotiating with local chiefs/administrative authorities for access to grazing land, and collecting cattle tax from herders within the Ardorate. | ||

| Elder Herders’ councils deliberate on land disputes and access to grazing areas. | ||

| Herding is transferred via lineage and integral to pastoralists livelihood security | ||

| Kin obligations follow a structured pattern with Ardos managing herding practices, legitimating marriages, family cohesion, child upbringing, deaths, and funeral rites. | ||

| Discern the conditions for Social Justice/Security and coping strategies impacting Pastoralist Livelihoods | Livelihood Strategies | Pastoralists are proud of earning a livelihood from cattle rearing, which is connected to their lineage. |

| Cattle herds are integral to pastoralists and a major means of income and livelihood security. | ||

| Ardos inculcate “good herding practices” taught in Fulani schools and passed on through epic stories, folktales, and songs. | ||

| Gendered task descriptors facilitate pastoralist livelihoods strategies. | ||

| Pastoralist communities have intrinsic birthing practices, prescribed gender roles and kin social obligations. | ||

| Through community social events, core knowledge on livestock practices is shared like training younger herders on cattle grazing and other skills like rope making, horse riding and cattle care. | ||

| Young pastoralist women are trained in restraining and milking cows, including cooking; cleaning and fetching water to ensure a stable household. | ||

| Livelihood Challenges | With shrinking pastures, pastoralists are constantly seeking new grazing opportunities which adds to demographic pressures on land, resulting in perennial farmer-herder problems. | |

| Elderly and Frail herders are unable to walk for long distances in search of green pasture and rely on younger herders. | ||

| Ethnic tensions and land disputes are often a trigger for concomitant conflicts with farming communities which jeopardizes livelihoods. | ||

| Pastoralists encounter problems finding suitable markets for their produce including dairy products. | ||

| When diseases affect cattle, pastoralists are stigmatized as ‘strangers’, and/or ‘foreigners’ and incur very costly veterinary services. | ||

| In comparison with other ethnic groups, pastoralists feel stigmatized for being uneducated; literacy programs are a pressing need. | ||

| Pastoralists rely on lineage/heritage support systems to fight against stigmatization, discrimination, marginalization, exploitation, and oppression. | ||

| Pastoralists’ grazing lands are constantly under threat, and they must travel longer distances to search for pasture, including the high cost of veterinary services in treating their cattle. | ||

| Pastoralists are often engaged in lingering court sessions that keep them away from their livelihood activity. | ||

| Uncover the implications of Ecology (human-environment nexus | Environmental Impact and Sustainable development initiatives | Pastoralist livelihoods are vulnerable to varied environmental conditions. |

| Pastoralist repositories of knowledge and landscape suitability are disseminated through folklore fostering interactions between livestock and the environment. | ||

| Land degradation exacerbates movements over long distances in search of good pastures with limited access to veterinary services in remote areas. | ||

| Cattle folklore describes livestock watering, grazing movements and coping with environmental stress. | ||

| Pastoralists feel disenfranchised from accessing land, water and electricity available to other communities. | ||

| In search of suitable grazing areas, pastoralists are constantly in fear of being chased away from areas found to be suitable for herding. | ||

| Recovery after droughts, climate variability and change remain a challenge to resilience in pastoralist communities. | ||

| Social Security and Sustainability concerns | Women depend on men for livelihoods decisions and suffer disproportionately, if risks and vulnerabilities are not addressed. | |

| Pastoralists feel left out of existing social welfare schemes, available in other ethnic communities. | ||

| Kindred and kin protection are vital forms of social insurance in retirement. | ||

| Pastoralists have limited government support in retirement even though they pay taxes to the state. | ||

| To facilitate access to social services, pastoralists offer bribes to administrative officials, albeit being exploited by gaining little in return. | ||

| Accused of using unorthodox means like bribing officials to access land and forms of social security. | ||

| Feeling of not receiving fair judgements in Court since they are perceived as occupiers without land rights. | ||

| Pastoralists are complaining of not having land rights because they are considered intruders or foreigners even by administrative authorities. | ||

| Pastoralists receive minimal social support from the state. | ||

| Livelihoods and Decision-Making | Pastoralists perceived by other ethnic communities as wealthy, influential, and able to manipulate administrative authorities | |

| Men in herder households are responsible for decision-making and activities regarding cattle movement, access to health, and sale of cattle while their spouses have milking rights. | ||

| Pastoralist elites who are the mouthpiece of their community are perceived to be exploiting their peers. | ||

| Youthful herders feel relegated from mainstream activities of MBOSCUDA and feel projects do not focus on their livelihood concerns. |

7. Discussion

From the findings synthesized in Table 2, it is evident that pastoralist livelihoods are impacted by multifaceted factors, with implications for social justice in pastoralist communities from a political ecology perspective. As disclosed by interviewees, social justice instruments are difficult to deploy in fractious relations with local farming communities and other intersecting factors, undermining livelihoods in pastoralist communities [65]. Government support through tailored welfare and development packages for pastoralist communities is in short supply, even though pastoralists pay cattle tax (jangali). That is why pastoralists feel disenfranchised and deem their relationship with institutional authorities distant. Unarguably, human development and food security indicators remain low. The provision of public services in pastoral zones is fragile and generally far lower than in other areas of a given country [5]. As the findings reveal, mobility is the backbone of pastoralism. Yet, local/government agencies, donors, and international stakeholders have not recognized the need to design, implement or fund projects and programs considering asset diversification and income generation [1]. Diminished herding and limited livelihood diversification strategies have not spurred external intervention, which is minimal and unsettling for social justice mechanisms to work effectively. Overall, the findings show pastoral systems are under many constraints, and potential risks and vulnerabilities have intensified. Pastoralists struggle to adapt and remain flexible [8] but need support [1].

As a sequel to the risks and vulnerabilities, research elsewhere [60] has documented pastoralists’ transformation process through a sustainable development approach. Our proposed SJEF underlines the importance of considering pastoralists’ livelihoods from political ecology and indigenous lens, and advocates for internal and external mandates for intervention and implementation. This is also justified by Loewe [66], who posits that governments and international development agencies should recognize that “the broader goals of social protection can only be achieved when the different components of the social protection system talk to each other and are synchronized across policies, programs, and the delivery chain”. (p. 23). We argue that the tripartite linkages between indigenous know-how, social justice and political ecology established in the SJEP is a possible “social justice/protection system” required to safeguard pastoralists’ livelihoods.

It is averred that social protection policies and programs have a crucial role in promoting the resilience of marginal populations living in dryland regions [1,46]. The political ecology perspective is relevant as policy on environmental factors could address the challenges plaguing vulnerable pastoralist communities [45]. Although pastoral systems are clearly under numerous constraints and risks have intensified, pastoralists are adapting and trying to remain flexible [8]. Governance of local risks is crucial in enabling pastoralist communities to address livelihood shocks.

Such governance strategies may include core assessments on aspects of vulnerability to inform a reevaluation of local-level development policies. In this vein, documenting, demarcating, and monitoring farming plots, designated grazing areas, and green pasture hubs is paramount to minimizing herder–farmer conflicts. Inevitably, these forms of support risk being diluted further due to pressures on land, urbanization, and climate change, which are unsettling [1]. Nevertheless, other mitigating measures like targeting pastoralists through vital social services, deploying social workers, literacy schemes, and other forms of social assistance informed by needs identification and problem-solving strategies are necessary to build on pastoralists’ inner strengths and resources.

Equally, greater access to veterinary services, primary education, youth vocational programs, essential services, and infrastructure development such as roads, drinkable water, power supply, schools, and health clinics, especially for sedentary pastoralists, are crucial. These services will better equip the Ardorate to fulfill its social justice mandate. Service delivery models could incorporate targeted literacy programs, distance learning, alternative solutions in community health, and other development strategies that can bolster pastoralists’ knowledge and skills in best herding practices. With the pastoralists’ livelihood challenges, the availability of veterinary services and public health infrastructure could stem the tide of out-migration by the younger generation seeking such amenities away from neglected pastoralist settlements.

Environmental concerns and climate change emerged as significant contending factors impacting livelihoods. Government interventions could focus on revitalizing livestock conditions to augment resilient pastoral systems, such as restocking and safeguarding their rights regarding mobility and transhumance during peak seasonal cultivation and grazing periods. This requires participatory policymaking and implementation to ensure the right to self-determination is mandatory [54], building on the expertise of pastoralists [1]. A valuable way of guaranteeing social justice requires helping pastoralists diversify their activities and mitigate the risks associated with climate variability. Ministerial departments involved could upgrade services and infrastructure (roads, water, power supply, rural employment) to address inequality and increasing levels of poverty, out-migration, and urbanization, which are forcing pastoralists out of their enclaves, and, in the process, diminishing the potential pool of human capital for buffering livelihood shocks.

Since cattle are at the heart of kin reciprocity and resilience, introducing more resistant cattle breeds, training in improving milk quality and production levels, and herding other animals such as goats, sheep, and chickens would allow pastoralist households to generate more income. Smith and Frankenberger [2] opine that resilience projects can optimize impacts on households’ ability to recover from livelihood shocks by layering interventions in a cross-sectoral approach. As captured in the SJEF, we argue that resilience-building measures from early warning systems, humanitarian aid, water development, service provision, and income diversification must be better targeted [1,3].

From the interviews, an indigenous approach to pastoralist administration and governance is imperative. In this light, the Ardos (Fulani leaders) are key players and stakeholders in upholding pastoralist traditions and establishing linkages with other communities. Therefore, a social justice ecosystem approach, calibrated around the Pulaaku, offers an indigenous governance system and allows pastoralists to build a sustainable social justice system. Pastoralist kin solidarity that has existed for generations is integral to livelihoods. Nevertheless, such traditional safety nets and informal mechanisms are increasingly fragmented due to livelihood challenges and unplanned external interventions. Efforts to secure demarcated grazing sites for seasonal herding practices and land rights are central to kin solidarity and resilience in buffering livelihood shocks.

Secured access to land and other ways of securing livelihoods would guarantee social justice for everyone. While grazing permits obtained from the Ministry of Livestock could be a way out, land demarcation for pastoralists, in consultation with neighboring communities, is essential. Partnership policies to embed innovation, information transfer, and adaptation of livestock and herding practices in synergy with pastoralists, MBOSCUDA, and government departments such as Health, Agriculture and Rural Development, Livestock and Veterinary, Education, and Social Affairs, in tandem with development agencies would enhance livelihoods. Moreover, to improve veterinary care for ambulant pastoralists, governments, and other development partners could coordinate aid packages based on needs identification, documentation of migratory routes, and the best interventions to cater to these alterations. Mobile veterinary, educational, and healthcare services could be provided to improve livelihoods in sedentary communities, thereby enhancing sustainability.

Human rights issues require attention, therefore, the protection of human rights for indigenous populations, advocated by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, squares with the mandate of promoting social justice. The protection of pastoralist groups and their unique ethnic, cultural, and linguistic identity within the territories in which they live is vital. While sustainable development is essential in pastoral areas, it should not undermine pastoral livelihoods. External interventions should be co-created and implemented [10,62], with a mix of periodic short-term and long-term support that builds on pastoralist infrastructure [66]. From the proposed SJEF, embedding social justice to guarantee sustainable development requires a co-partnership approach with institutional authorities from a political ecology perspective, recognizing pastoralist traditions that have proved socially resilient.

Opportunities for joint-up project planning with state services, development agencies, and other donor organizations could create an atmosphere of meaningful partnership. A study on dairy sellers in Northwest Cameroon by Provost et al. [67] recommended extending dairy training within functional cooperatives, increasing on-farm diversification of crop and livestock activities, and supporting the agribusiness potential of the youth in non-urban settings. In addition, providing pastoralists access to cooperative societies and credit unions would provide financial stability. Thriving aspects of pastoralist traditions could be co-produced and implemented without crowding out pre-existing indigenous approaches. Therefore, consulting the tiered leadership structure within pastoralist communities is important for externally driven interventions to succeed. Projects should be adaptable to specific needs and circumstances [19]. Fundamentally, recalibrating the government policy approach to pastoralism and community development is mandatory to enhance livelihoods and sustainability.

In resolving social vulnerabilities visible in pastoralist communities, policies should be premised on a problem-solving model, co-existence with neighboring farming communities through local decision-making, and active participation of local chiefs and Ardos. This would enable pastoralists to buffer livelihood shocks and address inherent vulnerabilities, enhancing sustainable development. The ILO [12] ‘Social Security Floor’ initiative (recommendation 202), which establishes a minimum level of social protection for all citizens, remains unimplemented. These efforts could cater to many low-income families, usually based on social assistance principles [17] (p. 187).

8. Conclusions and Pathways for Sustainable Development

This paper explores pastoralists’ livelihood challenges to understand the enmeshments of social justice, indigenous knowledge, and sustainability. Through a qualitative case study and informed by theorization of political ecology and indigenous knowledge, we have shed light on the challenges of implementing a social justice/security system affecting pastoralist livelihoods. Pastoralist livelihood strategies are intricately connected with cattle herding and traditional social/indigenous structures that enable or hinder livelihoods and sustainable development. A compendium of factors exacerbating risk and vulnerability within pastoralist communities are related to pressure on grazing land due to shrinking pasture, ethnic tension/conflict between pastoralists and host farming communities, barriers in accessing veterinary services, stigmatization, and the issue of ambulant/long distances trave, in search for green pasture. The emergent findings, anchored on political ecology theory, indicate that pastoralists’ livelihoods are vulnerable to environmental and climatic conditions, whilst indigenous know-how is instrumental in pastoralists’ adaptation to these environmental stressors and other intersecting factors. From a policy angle, there is ample evidence of the role of government in fostering community-level decision-making that enables pastoralists, who feel disenfranchised, to be more involved in community development ventures. Pastoralists’ livelihoods are undermined by a lack of access to essential livestock services, including land, water, and pasture.

It is clear that pastoralists’ livelihoods are gendered, and women rely on men for their livelihoods; however, the exclusion from social welfare schemes, unavailability of old-age insurance, and discriminatory treatment hit women the hardest. Pastoralists wrestle with other challenges, including vying for land rights, perennial herder–farmer conflicts, and environmental and climate change threats, jeopardizing livelihoods and social justice and undermining sustainability in pastoralist communities.