Comparative Analysis of Stakeholder Integration in Education Policy Making: Case Studies of Singapore and Finland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Understanding Stakeholder Integration in Educational Policymaking

3. Methods

4. The Singapore and Finland Models of Education Governance

4.1. The Singapore Model: Centralized Governance System

Stakeholder Engagement Strategies

4.2. The Finland Model: Decentralized Governance System

Stakeholder Engagement Strategies

5. Comparing Stakeholder Roles in the Singaporean and Finnish Educational Systems

6. Conclusions

7. Recommendations

- -

- Variability in engagement—stakeholder engagement is not monolithic and can manifest in various forms influenced by the governance model in place;

- -

- Impact on education outcomes—the active and intentional engagement of primary stakeholders, namely, teachers, parents, and students, has a direct and significant impact on educational outcomes and student performance;

- -

- Contextual flexibility—as the two nations demonstrate, successful stakeholder engagement is feasible in centralized and decentralized policy contexts;

- -

- Preparedness and respect for stakeholders—both nations highly respect their teachers and invest heavily in professional development to prepare stakeholders for meaningful participation in policy formulation and implementation;

- -

- Linking stakeholder engagement to economic objectives—effective stakeholder engagement with the private sector is crucial for aligning educational objectives with economic needs and creating a workforce to meet current and future challenges.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OECD. Implementing Education Policies Improving School Quality in Norway The New Competence Development Model; OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Joshua, A.A. Principals and parents partnership for sustainable quality assurance in Nigerian secondary schools. Int. Proc. Econ. Dev. Res. 2014, 81, 140. [Google Scholar]

- Ayeni, A.J. Improving school and community partnership for sustainable quality assurance in secondary schools in Nigeria. Int. J. Res. Stud. Educ. 2012, 1, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.J.J. Leading Effectively for K-12 School Improvement. In Leading and Managing Change for School Improvement; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gichohi, G.W. Stakeholder involvement in schools in 21st century for academic excellence. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2015, 3, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mashau, T.S.; Kone, L.R.; Mutshaeni, H.N. Improving participation in quality education in South Africa: Who are the stakeholders? Int. J. Educ. Sci. 2014, 7, 559–567. [Google Scholar]

- Ainscow, M. Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nord. J. Stud. Educ. Policy 2020, 6, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, J.; Hollweck, T. Inclusion and equity in education: Current policy reform in Nova Scotia, Canada. Prospects 2020, 49, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, M.E. A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondinelli, D.A.; Nellis, J.R.; Cheema, G.S. Decentralization in developing countries. World Bank Staff. Work. Pap. 1983, 581, 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Conyers, D. Decentralisation and development: A framework for analysis. Community Dev. J. 1986, 21, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinn, N.; Welsh, T. Decentralization of Education: Why, When, What and How? UNESCO: Paris, France, 1999; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000120275 (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Mwinjuma, J.S.; Hamzah, A.; Basri, R. A Review of Characteristics and Experiences of Decentralization of Education. Int. J. Educ. Lit. Stud. 2015, 3, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hanushek, E.A.; Link, S.; Woessmann, L. Does school autonomy make sense everywhere? Panel estimates from PISA. J. Dev. Econ. 2013, 104, 212–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- al Farid Uddin, K. Decentralisation and Governance. Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, S.P. The New Public Governance? Emerging Perspectives on the Theory and Practice of Public Governance, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; p. xv. [Google Scholar]

- Honig, M.I. New Directions in Education Policy Implementation: Confronting Complexity; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, E.M. Educational Decentralization: Issues and Challenges. 1997. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mark-Hanson-7/publication/44832286_Educational_Decentralization_Issues_and_Challenges/links/5575eacd08aeb6d8c01ae79f/Educational-Decentralization-Issues-and-Challenges.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Bacchus, K. Some problems and challenges faced in decentralizing education in small states. In Policy, Planning and Management of Education in Small States; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1993; pp. 76–93. [Google Scholar]

- Adolfsson, C.-H.; Alvunger, D. Power dynamics and policy actions in the changing landscape of local school governance. Nord. J. Stud. Educ. Policy 2020, 6, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androniceanu, A.; Ristea, B. Decision making process in the decentralized educational system. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 149, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çınkır, Ş. Perceptions of educational stakeholders about decentralizing educational decision making in Turkey. Educ. Plan. 2010, 19, 22–36. [Google Scholar]

- Padayachee, A.; Naidu, A.; Waspe, T. Structure and governance of systems, stakeholder engagement, roles and powers. In Twenty Years of Education Transformation in Gauteng 1994 to 2014; African Minds: Cape Town, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hail, M.A.; Al-Fagih, L.; Koç, M. Partnering for sustainability: Parent-teacher-school (PTS) interactions in the Qatar education system. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOE. Overview of Singapore Education System; MOE: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, K.H.; Tan, C.; Chua, J.S. Innovation in education: The ”teach less, learn more” initiative in Singapore schools. In Innovation in Education; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 153–171. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, Y.C.; LIM, F.V. Teach Less, Learn More? Unravelling the Paradox with People Development. Hong Kong. 2006. Available online: http://edisdat.ied.edu.hk/pubarch/b15907314/full_paper/1115649590.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Gomez, J.; Ooi, C.-S. Introduction: Stability, Risks and Opposition in Singapore. Cph. J. Asian Stud. 2006, 23, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwek, D.; Teng, S.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Chan, M. Policy and pedagogical reforms in Singapore: Taking stock, moving forward. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2020, 40, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, O.-S.; Liu, W.-C.; Low, E.-L. Teacher education in the 21st century. In Teacher Education in the 21st Century; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, T.W.; Choy, B.H. STEM Education in Singapore. In Singapore Math and Science Education Innovation: Beyond PISA; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.H.; Gopinathan, S. Centralized decentralization of higher education in Singapore. In Centralization and Decentralization: Educational Reforms and Changing Governance in Chinese Societies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 117–136. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, K.h. Decentralization and marketization of education in Singapore: A case study of the school excellence model. J. Educ. Adm. 2003, 41, 348–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Ng, P.T. Dynamics of change: Decentralised centralism of education in Singapore. J. Educ. Chang. 2007, 8, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOE. Communications and Engagement Group. Available online: https://www.moe.gov.sg/about-us/organisation-structure/ceg (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Khong, L.Y.L. Schools Engaging Parents in Partnership: Supporting Lower-Achieving Students in Schools; National Institution of Education: Singapore, 2016; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/68028934/Schools_engaging_parents_in_partnership_Supporting_lower_achieving_students_in_schools (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- MOE. Parent Support Group; MOE: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pak Tee, N. The Singapore school and the school excellence model. Educ. Res. Policy Pract. 2003, 2, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.H.; Gurr, D.; Drysdale, L. Successful school leadership: Case studies of four Singapore primary schools. J. Educ. Adm. 2016, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britannica. Finland; Britannica: Edinburgh, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Valtioneuvosto. The Government and Parliament. Available online: https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/government/the-government-and-parliament (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- OECD. Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development; OECD: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ylönen, M.; Salmivaara, A. Policy coherence across Agenda 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals: Lessons from Finland. Dev. Policy Rev. 2021, 39, 829–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lähteenoja, S.; Schmidt-Thomé, K.; Päivänen, J.; Terämä, E. The Leadership and Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals in Finnish Municipalities. In Sustainable Development Goals for Society Vol. 1: Selected Topics of Global Relevance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 203–217. [Google Scholar]

- PMO. Government Report on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Sustainable Development in Finland—Long-Term, Coherent and Inclusive Action; Prime Minister’s Office: Helsinki, Finland, 2017.

- Lavonen, J. Governance decentralisation in education: Finnish innovation in education. In Revista De Educación a Distancia (RED); Finland; 2017; Available online: https://www.um.es/ead/red/53/lavonen.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Risku, M. A historical insight on Finnish education policy from 1944 to 2011. Ital. J. Sociol. Educ. 2014, 6, 36–68. [Google Scholar]

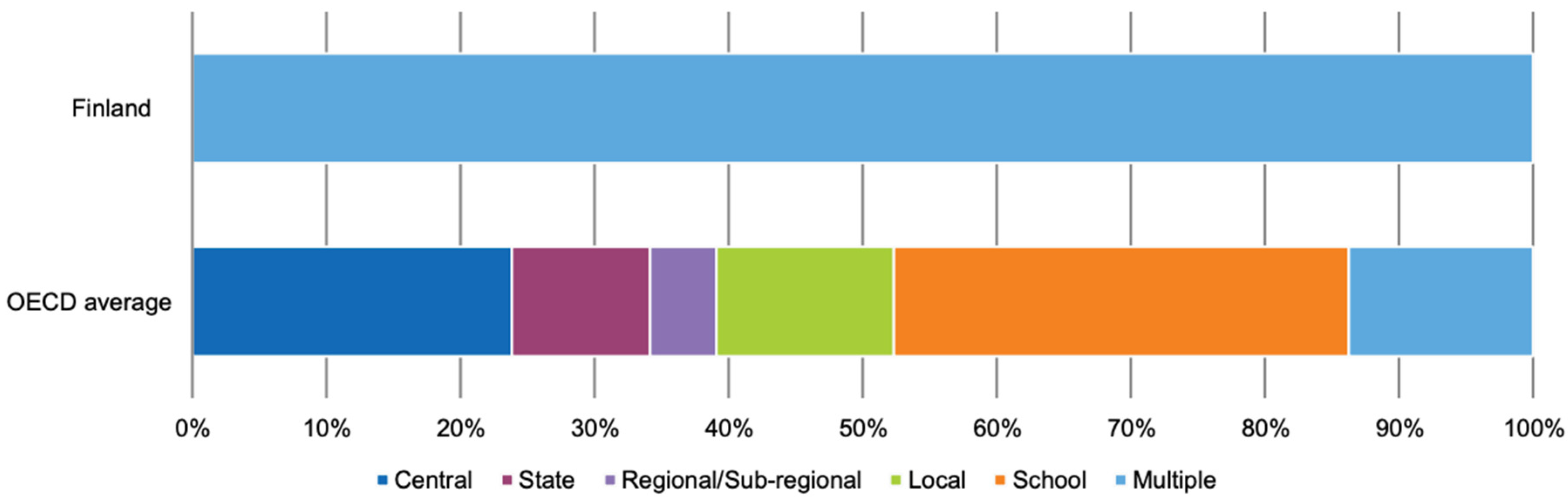

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2020 Finland; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Education Policy Outlook Finland; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- EDUFI. Education in Finland; EDUFI: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ustun, U.; Eryilmaz, A. Analysis of Finnish Education System to Question the Reasons behind Finnish Success in PISA. Online Submiss. 2018, 2, 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, H. Review of research: The education system in Finland: A success story other countries can emulate. Child. Educ. 2014, 90, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, H. Education Reforms for Equity and Quality: An Analysis from an Educational Ecosystem Perspective with Reference to Finnish Educational Transformations. Cent. Educ. Policy Stud. J. 2021, 11, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FINEEC. Information Production on Focus Areas. Available online: https://karvi.fi/en/fineec/information-production-on-focus-areas/ (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- FINEEC. Development of Operations. Available online: https://karvi.fi/en/fineec/development-of-operation/ (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- Kauko, J.; Varjo, J.; Pitkänen, H. Quality and evaluation in Finnish schools. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- FINEEC. Stakeholder Survey 2022. Available online: https://www.karvi.fi/fi/sidosryhmakysely-2022 (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- OECD. PISA 2018 Results; OECD publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Renko, V.; Johannisson, J.; Kangas, A.; Blomgren, R. Pursuing decentralisation: Regional cultural policies in Finland and Sweden. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2022, 28, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.Y.; Dimmock, C. How a ‘top-performing’Asian school system formulates and implements policy: The case of Singapore. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2014, 42, 743–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.K. Beyond decentralization: Changing roles of the state in education. In Centralization and Decentralization: Educational Reforms and Changing Governance in Chinese Societies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Sclafani, S.K. Singapore chooses teachers carefully. Phi Delta Kappan 2015, 97, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gareis, C.R. Teacher Effectiveness in Singapore: Valuing Teachers as Learners. In International Beliefs and Practices That Characterize Teacher Effectiveness; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 192–226. [Google Scholar]

- Malinen, O.-P.; Väisänen, P.; Savolainen, H. Teacher education in Finland: A review of a national effort for preparing teachers for the future. Curric. J. 2012, 23, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnanen, M.; Palviainen, Å. Finnish teachers as policy agents in a changing society. Lang. Educ. 2018, 32, 428–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, C.Y.; Cheung, A.C. School engagement and parental involvement: The case of cross-border students in Singapore. Aust. Educ. Res. 2014, 41, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khong, L.Y.-L.; Ng, P.T. School–parent partnerships in Singapore. Educ. Res. Policy Pract. 2005, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Männistö, P.M.; Moate, J. A phenomenological research of democracy education in a Finnish primary-school. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, B.L.; Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C.; Purnell, L.; De Colle, S. Stakeholder theory: The state of the art. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2010, 4, 403–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, M. Developing a robust system for upskilling and reskilling the workforce: Lessons from the SkillsFuture movement in Singapore. In Anticipating and Preparing for Emerging Skills and Jobs: Key Issues, Concerns, and Prospects; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, M.; Taal, R.; Sim, W. SkillsFuture: The roles of public and private sectors in developing a learning society in Singapore. Powering A Learn. Soc. Dur. Age Disrupt. 2021, 58, 195. [Google Scholar]

- Toni, A.; Vuorinen, R. Lifelong guidance in Finland: Key policies and practices. In Career and Career Guidance in the Nordic Countries; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 127–143. [Google Scholar]

| Sector | Stakeholder |

|---|---|

| School Level | Educators |

| School leaders | |

| Community Level | Parents |

| Students | |

| Community members | |

| Unions | |

| NGOs | |

| Media and news agencies | |

| Community bloggers | |

| Government Level | Parliament members |

| Representatives of other ministries | |

| Government agencies | |

| Private Sector | Employers |

| Industry associations | |

| Training providers |

| Criteria | Singapore | Finland |

|---|---|---|

| Policy Context | ||

| Governance Structure | Centralised | Decentralised |

| Key Education Policies and Initiatives | ‘Teach Less, Think More’ and ‘Thinking Schools’ | ‘Lifelong Learning’ |

| National Education Priority | Economic development and social cohesion | Equality, quality, efficiency and well-being |

| Stakeholder Engagement Strategies | ||

| Teachers | Limited formal representation but active in school-level decisions | Teachers involved in policy formation at multiple levels |

| Parents and Students | Active in school activities, indirectly engaged in policy development and implementation through school-level discussion groups | Actively involved, often through advisory boards |

| Private Sector and NGOs | Actively involved in lifelong learning initiatives ‘SkillsFuture’ | Actively involved in lifelong learning initiatives and vocational education and training programs |

| Challenges | ||

| Representation in Policymaking | The limited representation of teachers in formal councils. Teachers, parents and students are more enablers than agents of policy initiatives. | A consensus-driven model may slow down policy decisions |

| Inclusivity and Diversity | Focusing on high achievement could marginalise certain groups. | Balancing equality with excellence |

| Adaptability | Rigidity due to the centralised structure | May struggle with rapid policy changes due to multiple stakeholder inputs |

| Country | Global Ranking | PISA (2018) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reading | Mathematics | Science | ||

| Singapore | 2 | 549 | 569 | 551 |

| Finland | 7 | 520 | 507 | 522 |

| OECD Average | 487 | 489 | 489 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Thani, G. Comparative Analysis of Stakeholder Integration in Education Policy Making: Case Studies of Singapore and Finland. Societies 2024, 14, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14070104

Al-Thani G. Comparative Analysis of Stakeholder Integration in Education Policy Making: Case Studies of Singapore and Finland. Societies. 2024; 14(7):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14070104

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Thani, Ghalia. 2024. "Comparative Analysis of Stakeholder Integration in Education Policy Making: Case Studies of Singapore and Finland" Societies 14, no. 7: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14070104