Influential Factors Affecting the Intention to Utilize Advance Care Plans (ACPs) in Thailand and Indonesia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Advance Care Planning

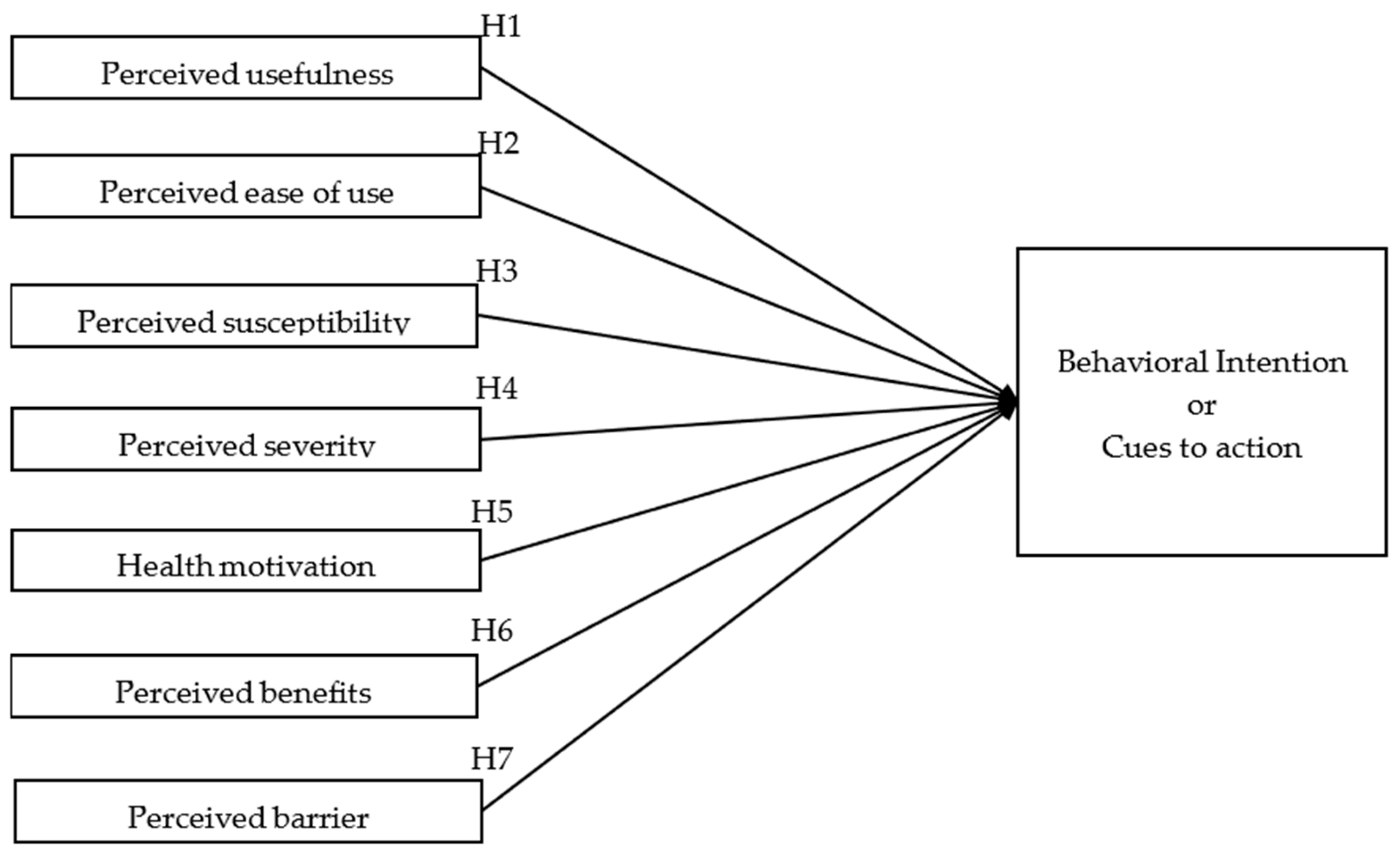

2.2. Proposed Conceptual Framework

2.2.1. Perceived Usefulness

2.2.2. Perceived Ease of Use

2.2.3. Perceived Susceptibility

2.2.4. Perceived Severity

2.2.5. Health Motivation

2.2.6. Perceived Benefits

2.2.7. Perceived Barriers

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design

3.2. Participants

3.2.1. Recruitment

3.2.2. Sample Size and Characteristics

3.2.3. Measures

3.2.4. Procedures

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Validity and Reliability

4.3. Testing Hypothesis

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| ACP | Advance care plan/planning |

| ACPs | Advance care plans |

| TAM | Technology acceptance model |

| UTAUT | Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology |

| HBM | Health belief model |

| PU | Perceived the usefulness |

| PEOU | Perceived ease of use |

| PSU | Perceived susceptibility |

| PSE | Perceived severity |

| HM | Health motivation |

| PBE | Perceived benefits |

| PBA | Perceived barriers |

| BI | Behavioral intention |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| AVE | Average variance extracted |

| VIF | Variance inflation factor |

| HTMT | Heterotrait–Monotrait |

Appendix A

| Construct | Measurement Items | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived usefulness (PU) | PU1 | Using the health care application improved my everyday life quality | [102] |

| PU2 | Using the health care application enhanced my effectiveness on taking care of myself and my family | ||

| PU3 | I found the health care application useful in my everyday life | ||

| Perceived ease of use (PEOU) | PEOU1 | Learning to use the health care application is easy for me | [58,103] |

| PEOU2 | My interaction with the health care application has been understandable | ||

| PEOU3 | It is easy to become skillful at using the health care application | ||

| Perceived susceptibility (PSU) | PSU1 | It is likely that I will get a chance to have a palliative care giver. | [63] |

| PSU2 | I feel knowledgeable about my risk of getting a chance to have a palliative care giver | ||

| PSU3 | Perceived chances of contracting with some serious disease? | ||

| Perceived severity (PSE) | PSE1 | I feel that without this advance care plan application I won’t be able to return to my normal life because of the worry. | |

| PSE2 | I feel that if I do not use this application, I will have anything to precaution. | ||

| PSE3 | I will have to pay more for medical bills, if I have nothing to warn me with health condition. | ||

| Health Motivation (HM) | HM1 | Regularly the healthy behaviors have become the fundamental of my habits. | [70] |

| HM2 | I believe it’s a good thing I can do to feel better about myself in general. | ||

| HM3 | I think there are more important things to do than staying healthy. | ||

| Perceived Benefits (PBE) | PBE1 | The ACP application makes me feel safe and secure of health condition. | [72] |

| PBE2 | This service will facilitate the society. | ||

| PBE3 | This service will reduce the severity of health conditions. | ||

| Perceived Barriers (PBA) | PBA1 | This service will be difficult for me to use if available only on smartphones/tablets. | |

| PBA2 | This service will be difficult for me to access if offered exclusively in English. | ||

| PBA3 | I feel unsecure to disclose my personal data. | ||

| Behavioral Intention or Cues to action (BI) | BI1 | I am interested and expect to use this ACP application in the future. | |

| BI2 | I plan to use this ACP application in the future. | ||

| BI3 | I predict I will use this ACP application in the future. |

Appendix B. Discriminant Validity

- a.

- Fornell–Larcker

| BI | HM | PBA | PBE | PEOU | PSE | PSU | PU | |

| BI | 0.808 | |||||||

| HM | 0.464 | 0.803 | ||||||

| PBA | 0.222 | 0.310 | 0.861 | |||||

| PBE | 0.599 | 0.457 | 0.202 | 0.795 | ||||

| PEOU | 0.524 | 0.454 | 0.143 | 0.51 | 0.79 | |||

| PSE | 0.514 | 0.427 | 0.214 | 0.534 | 0.459 | 0.807 | ||

| PSU | 0.532 | 0.472 | 0.253 | 0.502 | 0.466 | 0.526 | 0.774 | |

| PU | 0.564 | 0.452 | 0.177 | 0.571 | 0.496 | 0.488 | 0.475 | 0.768 |

- b.

- Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT)

| BI | HM | PBA | PBE | PEOU | PSE | PSU | PU | |

| BI | ||||||||

| HM | 0.614 | |||||||

| PBA | 0.290 | 0.383 | ||||||

| PBE | 0.823 | 0.622 | 0.260 | |||||

| PEOU | 0.729 | 0.629 | 0.185 | 0.723 | ||||

| PSE | 0.701 | 0.576 | 0.268 | 0.740 | 0.637 | |||

| PSU | 0.753 | 0.665 | 0.349 | 0.726 | 0.671 | 0.743 | ||

| PU | 0.814 | 0.644 | 0.231 | 0.840 | 0.735 | 0.705 | 0.709 |

- c.

- Cross-loading

| BI | HM | PBA | PBE | PEOU | PSE | PSU | PU | |

| BI1 | 0.801 | 0.341 | 0.047 | 0.497 | 0.455 | 0.413 | 0.414 | 0.480 |

| BI2 | 0.815 | 0.392 | 0.272 | 0.500 | 0.394 | 0.410 | 0.447 | 0.467 |

| BI3 | 0.808 | 0.393 | 0.219 | 0.452 | 0.422 | 0.423 | 0.429 | 0.419 |

| HM1 | 0.461 | 0.863 | 0.302 | 0.406 | 0.400 | 0.381 | 0.448 | 0.403 |

| HM2 | 0.327 | 0.778 | 0.209 | 0.391 | 0.349 | 0.340 | 0.293 | 0.394 |

| HM3 | 0.299 | 0.765 | 0.220 | 0.294 | 0.339 | 0.299 | 0.379 | 0.278 |

| PBA1 | 0.213 | 0.305 | 0.896 | 0.179 | 0.115 | 0.179 | 0.238 | 0.167 |

| PBA2 | 0.206 | 0.274 | 0.885 | 0.214 | 0.142 | 0.231 | 0.230 | 0.184 |

| PBA3 | 0.143 | 0.208 | 0.799 | 0.112 | 0.112 | 0.132 | 0.178 | 0.089 |

| PBE1 | 0.539 | 0.417 | 0.133 | 0.839 | 0.445 | 0.446 | 0.425 | 0.468 |

| PBE2 | 0.440 | 0.356 | 0.226 | 0.773 | 0.433 | 0.417 | 0.408 | 0.447 |

| PBE3 | 0.440 | 0.309 | 0.131 | 0.771 | 0.334 | 0.412 | 0.363 | 0.449 |

| PEOU1 | 0.429 | 0.362 | 0.062 | 0.435 | 0.806 | 0.371 | 0.398 | 0.376 |

| PEOU2 | 0.437 | 0.384 | 0.193 | 0.384 | 0.815 | 0.401 | 0.368 | 0.411 |

| PEOU3 | 0.372 | 0.329 | 0.079 | 0.391 | 0.746 | 0.309 | 0.337 | 0.390 |

| PSE1 | 0.416 | 0.369 | 0.171 | 0.431 | 0.372 | 0.807 | 0.459 | 0.369 |

| PSE2 | 0.423 | 0.363 | 0.205 | 0.458 | 0.391 | 0.828 | 0.474 | 0.392 |

| PSE3 | 0.405 | 0.300 | 0.143 | 0.404 | 0.347 | 0.786 | 0.338 | 0.421 |

| PSU1 | 0.471 | 0.368 | 0.131 | 0.417 | 0.422 | 0.453 | 0.822 | 0.436 |

| PSU2 | 0.412 | 0.390 | 0.233 | 0.408 | 0.372 | 0.430 | 0.801 | 0.375 |

| PSU3 | 0.340 | 0.341 | 0.246 | 0.334 | 0.271 | 0.325 | 0.692 | 0.274 |

| PU1 | 0.430 | 0.341 | 0.089 | 0.445 | 0.414 | 0.336 | 0.381 | 0.771 |

| PU2 | 0.434 | 0.379 | 0.161 | 0.456 | 0.376 | 0.378 | 0.375 | 0.772 |

| PU3 | 0.437 | 0.321 | 0.157 | 0.416 | 0.353 | 0.409 | 0.341 | 0.762 |

References

- Harper, S. Economic and Social Implications of Aging Societies. Science 2014, 346, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, J.W. Challenges for Middle-Income Elders in An Aging Society. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 865–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. World Social Report 2023: Leaving No One behind in an Ageing World; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Roberson, L.B.; Parker, K.A.; Ivanov, B.; Hester, E.B. Feasibility and Acceptability of Curricula to Promote Healthy Eating in the Golden Years. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2023, 51, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa, A.L.; Miranda, B.; Acosta, I. Links Between Mental Health and Physical Health, Their Impact on the Quality of Life of the Elderly, and Challenges for Public Health. In Understanding the Context of Cognitive Aging; Angel, J.L., López Ortega, M., Gutierrez Robledo, L.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollset, S.E.; Goren, E.; Yuan, C.-W.; Cao, J.; Smith, A.E.; Hsiao, T.; Bisignano, C.; Azhar, G.S.; Castro, E.; Chalek, J.; et al. Fertility, Mortality, Migration, and Population Scenarios for 195 Countries and Territories from 2017 to 2100: A Forecasting Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 2020, 396, 1285–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molassiotis, A.; Leung, A.Y.M.; Zhao, I.Y. Call for Urgent Actions in Societies and Health Systems in the Western Pacific Region to Implement the WHO Regional Action Plan on Healthy Ageing. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 2374–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Global Population Growth and Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Khavinson, V.; Popovich, I.; Mikhailova, O. Towards Realization of Longer Life. Acta Bio. Medica Atenei Parm. 2020, 91, e2020054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.M.; Milstein, A. Contributions of Health Care to Longevity: A Review of 4 Estimation Methods. Ann. Fam. Med. 2019, 17, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, N.; Sherratt, R.S.; Elhajj, I.H. Directing and Orienting ICT Healthcare Solutions to Address the Needs of the Aging Population. Healthcare 2021, 9, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ESCAP. Overview of Levels and Trends in Population Ageing, Including Emerging Issues, and Their Impact on Sustainable Development in Asia and the Pacific; ESCAP/MIPAA/IGM.3/2022/1; United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and World Health Organization: Bangkok, Thailand, 2022; Available online: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/event-documents/MIPAA_2022_IGM.3_1_E_reissued.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Chongsuvivatwong, V.; Phua, K.H.; Yap, M.T.; Pocock, N.S.; Hashim, J.H.; Chhem, R.; Wilopo, S.A.; Lopez, A.D. Health and Health-Care Systems in Southeast Asia: Diversity and Transitions. Lancet 2011, 377, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, T.Y.; Tran, T.L.; Prueksaritanond, S.; Isidro, J.; Setia, S.; Welluppillai, V. Integrated Health Care Systems in Asia: An Urgent Necessity. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 2527–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshon, J.M.; Risko, N.; Calvello, E.J.; Stewart De Ramirez, S.; Narayan, M.; Theodosis, C.; O’Neill, J.; for the Acute Care Research Collaborative at the University of Maryland Global Health Initiative. Health Systems and Services: The Role of Acute Care. Bull. World Health Organ. 2013, 91, 386–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manero, A.; Crawford, K.E.; Prock-Gibbs, H.; Shah, N.; Gandhi, D.; Coathup, M.J. Improving Disease Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment Using Novel Bionic Technologies. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2023, 8, e10359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, A.; Bayly, J.; Penfold, C.; Lin, C.; Oluyase, A.O.; Hocaoglu, M.B.; Murtagh, F.E.M.; Koffman, J. Comment on: “Advance” Care Planning Reenvisioned. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 1177–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedini, C.; Biotto, M.; Crespi Bel’skij, L.M.; Moroni Grandini, R.E.; Cesari, M. Advance Care Planning and Advance Directives: An Overview of the Main Critical Issues. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 34, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, M.S.; Anderson, B.; Cole, A.; Lyon, M.E. Documentation of Advance Directives and Code Status in Electronic Medical Records to Honor Goals of Care. J. Palliat. Care 2020, 35, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.; Hwang, K.; Watt, J.; Batchelor, F.; Gerber, K.; Hayes, B.; Brijnath, B. How Are Older People’s Care Preferences Documented towards the End of Life? Collegian 2020, 27, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischhoff, B.; Barnato, A.E. Value Awareness: A New Goal for End-of-Life Decision Making. MDM Policy Pract. 2019, 4, 238146831881752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sable-Smith, A.; Arnett, K.R.; Nowels, M.A.; Colborn, K.; Lum, H.D.; Nowels, D. Interactions with the Healthcare System Influence Advance Care Planning Activities: Results from a Representative Survey in 11 Developed Countries. Fam. Pract. 2018, 35, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Bynum, J.P.W.; Zhang, L.; Grodstein, F.; Stevenson, D.G. Predictors of Advance Care Planning in Older Women: The Nurses’ Health Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.-T.; Chen, C.-M.; Chung, M.-C.; Tsai, P.-Y.; Liu, Y.-T.; Tang, F.-C.; Lin, Y.-L. Important Factors Influencing Willingness to Participate in Advance Care Planning among Outpatients: A Pilot Study in Central Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 5266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pairojkul, S.; Raksasataya, A.; Sorasit, C.; Horatanaruang, D.; Jarusomboon, W. Thailand’s Experience in Advance Care Planning. Z. Für Evidenz Fortbild. Qual. Im Gesundheitswesen 2023, 180, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martina, D.; Kustanti, C.Y.; Dewantari, R.; Sutandyo, N.; Putranto, R.; Shatri, H.; Effendy, C.; Van Der Heide, A.; Van Der Rijt, C.C.D.; Rietjens, J.A.C. Advance Care Planning for Patients with Cancer and Family Caregivers in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study. BMC Palliat. Care 2022, 21, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirscht, J.P. The Health Belief Model and Predictions of Health Actions. In Health Behavior; Gochman, D.S., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1988; pp. 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, R.J.; Karsh, B.-T. The Technology Acceptance Model: Its Past and Its Future in Health Care. J. Biomed. Inform. 2010, 43, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.; Donnelly, S.; Morton, S.; Murphy, S. 293 Advance Care Planning in Older Persons Mental Health, Insights from Interdisciplinary Healthcare Professionals. Age Ageing 2023, 52 (Suppl. 3), afad156.232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canny, A.; Mason, B.; Atkins, C.; Patterson, R.; Moussa, L.; Boyd, K. Online Public Information about Advance Care Planning: An Evaluation of UK and International Websites. Digit. Health 2023, 9, 20552076231180438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuusisto, A.; Santavirta, J.; Saranto, K.; Haavisto, E. Healthcare Professionals’ Perceptions of Advance Care Planning in Palliative Care Unit: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, R.S.; Meier, D.E.; Arnold, R.M. What’s Wrong with Advance Care Planning? JAMA 2021, 326, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.-H.; Lee, C.; Yoo, J. Culture Differences in Advance Care Planning and Implications for Social Work Practice. Innov. Aging 2021, 5 (Suppl. 1), 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobylarz, F.; Kim, H.; Zafar, A.; Lin, H.; Lopez, M.; Jarrín, O. Advanced Care Planning Services Billing Encounters among Medicare Beneficiaries Who Died in 2019. Innov. Aging 2023, 7 (Suppl. 1), 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, L.W.; O’Donnell, A. Advanced Care Planning. JACC Heart Fail. 2015, 3, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudore, R.L.; Lum, H.D.; You, J.J.; Hanson, L.C.; Meier, D.E.; Pantilat, S.Z.; Matlock, D.D.; Rietjens, J.A.C.; Korfage, I.J.; Ritchie, C.S.; et al. Defining Advance Care Planning for Adults: A Consensus Definition from a Multidisciplinary Delphi Panel. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 53, 821–832.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, A.J.; Luckett, T.; Clayton, J.M.; Gabb, L.; Kochovska, S.; Agar, M. Advance Care Planning in Different Settings for People with Dementia: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Palliat. Support. Care 2019, 17, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishikawa, Y.; Hiroyama, N.; Fukahori, H.; Ota, E.; Mizuno, A.; Miyashita, M.; Yoneoka, D.; Kwong, J.S. Advance Care Planning for Adults with Heart Failure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2020, CD013022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fink, R.M.; Somes, E.; Brackett, H.; Shanbhag, P.; Anderson, A.N.; Lum, H.D. Evaluation of Quality Improvement Initiatives to Improve and Sustain Advance Care Planning Completion and Documentation. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2019, 21, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowels, D.; Nowels, M.A.; Sheffler, J.L.; Kunihiro, S.; Lum, H.D. Features of U.S. Primary Care Physicians and Their Practices Associated with Advance Care Planning Conversations. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2019, 32, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahan, R.D.; Tellez, I.; Sudore, R.L. Deconstructing the Complexities of Advance Care Planning Outcomes: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go? A Scoping Review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lum, H.D.; Brungardt, A.; Jordan, S.R.; Phimphasone-Brady, P.; Schilling, L.M.; Lin, C.-T.; Kutner, J.S. Design and Implementation of Patient Portal–Based Advance Care Planning Tools. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2019, 57, 112–117.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allsop, M.J.; Chumbley, K.; Birtwistle, J.; Bennett, M.I.; Pocock, L. Building on Sand: Digital Technologies for Care Coordination and Advance Care Planning. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2022, 12, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neale, J.; Onions, S.; Still, G. P-39 Integrated Care System (ICS) Approach to Digital Transformation of Advance Care Planning. In Poster Presentations; British Medical Journal Publishing Group: London, UK, 2021; p. A24.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, C.; Smets, T.; Monnet, F.; Pivodic, L.; De Vleminck, A.; Van Audenhove, C.; Van Den Block, L. Publicly Available, Interactive Web-Based Tools to Support Advance Care Planning: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e33320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, V. Innovation Diffusion. In Wiley International Encyclopedia of Marketing; Sheth, J., Malhotra, N., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhakami, A.S.; Slovic, P. A Psychological Study of the Inverse Relationship Between Perceived Risk and Perceived Benefit. Risk Anal. 1994, 14, 1085–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, N.D. Perceived Probability, Perceived Severity, and Health-Protective Behavior. Health Psychol. 2000, 19, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkhalifa, A.M.E.; Ahmed, B.H.; ELMobarak, W.M. Factors That Influence E-Health Applications from Patients’ Perspective in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: An Exploratory Study. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 109029–109042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.; Hegarty, F.; Amoore, J.; Blackett, P.; Scott, R. Health Technology Asset Management. In Clinical Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.T.; Rogers, W.A. Developing a Healthcare Technology Acceptance Model (H-TAM) for Older Adults with Hypertension. Ageing Soc. 2023, 43, 814–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Adwan, A.S.; Li, N.; Al-Adwan, A.; Abbasi, G.A.; Albelbisi, N.A.; Habibi, A. Extending the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to Predict University Students’ Intentions to Use Metaverse-Based Learning Platforms. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 15381–15413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, V.; Bala, H. Technology Acceptance Model 3 and a Research Agenda on Interventions. Decis. Sci. 2008, 39, 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Luximon, Y.; Qin, M.; Geng, P.; Tao, D. The Determinants of User Acceptance of Mobile Medical Platforms: An Investigation Integrating the TPB, TAM, and Patient-Centered Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 10758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.J.; Chun, J.U.; Song, J. Investigating the Role of Attitude in Technology Acceptance from an Attitude Strength Perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2009, 29, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldosari, B. User Acceptance of a Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) in a Saudi Arabian Hospital Radiology Department. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2012, 12, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Chau, P.H.; Cheung, D.S.T.; Ho, M.; Lin, C. Preferences for End-of-life Care: A Cross-sectional Survey of Chinese Frail Nursing Home Residents. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 1455–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, M.-H.; Liu, H.-C.; Joo, J.Y.; Lee, J.J.; Liu, M.F. Critical Care Nurses’ Knowledge and Attitudes and Their Perspectives toward Promoting Advance Directives and End-of-Life Care. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janz, N.K.; Becker, M.H. The Health Belief Model: A Decade Later. Health Educ. Q. 1984, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saffari, M.; Sanaeinasab, H.; Rashidi-jahan, H.; Aghazadeh, F.; Raei, M.; Rahmati, F.; Al Zaben, F.; Koenig, H.G. An Intervention Program Using the Health Belief Model to Modify Lifestyle in Coronary Heart Disease: Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2023. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Paoli, M.M.; Manongi, R.; Klepp, K.-i. Factors Influencing Acceptability of Voluntary Counselling and HIV-Testing among Pregnant Women in Northern Tanzania. AIDS Care 2004, 16, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T.; Martina, D.; Heide, A.V.D.; Korfage, I.J.; Rietjens, J.A. The Role of Acculturation in the Process of Advance Care Planning among Chinese Immigrants: A Narrative Systematic Review. Palliat. Med. 2023, 37, 1063–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.K.; Fried, T.R.; Costello, D.M.; Hajduk, A.M.; O’Leary, J.R.; Cohen, A.B. Perceived Dementia Risk and Advance Care Planning among Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 1481–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, L.S.; Breitbart, W.; Prigerson, H.G. “My Family Wants Something Different”: Discordance in Perceived Personal and Family Treatment Preference and Its Association with Do-Not-Resuscitate Order Placement. J. Oncol. Pract. 2019, 15, e942–e947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, H.E.; Duke, S.; Richardson, A. Paediatric Advance Care Planning in Life-Limiting Conditions: Scoping Review of Parent Experiences. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2023, 13, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Kiekhofer, R.E.; Hooper, S.M.; Dulaney, S.; Possin, K.L.; Chiong, W. Goals of Care Conversations and Subsequent Advance Care Planning Outcomes for People with Dementia. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2021, 83, 1767–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Iwanaga, M.; Roth, R.; Hamasaki, T.; Greimel, E. Psychometric Validation of the Motivation for Healthy Eating Scale (MHES). Psychology 2013, 4, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnet, F.; Diaz, A.; Gove, D.; Dupont, C.; Pivodic, L.; Van Den Block, L. The Perspectives of People with Dementia and Their Supporters on Advance Care Planning: A Qualitative Study with the European Working Group of People with Dementia. Palliat. Med. 2024, 38, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dujardin, J.; Schuurmans, J.; Westerduin, D.; Wichmann, A.B.; Engels, Y. The COVID-19 Pandemic: A Tipping Point for Advance Care Planning? Experiences of General Practitioners. Palliat. Med. 2021, 35, 1238–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Steen, J.T.; Nakanishi, M.; Van Den Block, L.; Di Giulio, P.; Gonella, S.; In Der Schmitten, J.; Sudore, R.L.; Harrison Dening, K.; Parker, D.; Mimica, N.; et al. Consensus Definition of Advance Care Planning in Dementia: A 33-country Delphi Study. Alzheimers Dement. 2023, 20, 1309–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niculaescu, C.-E.; Sassoon, I.K.; Landa-Avila, I.C.; Colak, O.; Jun, G.T.; Balatsoukas, P. Using the Health Belief Model to Design a Questionnaire Aimed at Measuring People’s Perceptions Regarding COVID-19 Immunity Certificates. Public Glob. Health 2021. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlewood, J.; Hinchcliff, R.; Lo, W.; Rhee, J. Advance Care Planning in Rural New South Wales from the Perspective of General Practice Registrars and Recently Fellowed General Practitioners. Aust. J. Rural Health 2019, 27, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results; Statistical Papers—United Nations (Ser. A), Population and Vital Statistics Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarte, J.M.; Barrios, E.B. Estimation Under Purposive Sampling. Commun. Stat.-Simul. Comput. 2006, 35, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongco, M.D.C. Purposive Sampling as a Tool for Informant Selection. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2007, 5, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A.E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Kale, S.; Chandel, S.; Pal, D. Likert Scale: Explored and Explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.-C.; Lin, I.-C. Performance Evaluation of an Information Technology Intervention Regarding Charging for Inpatient Medical Materials at a Regional Teaching Hospital in Taiwan: Empirical Study. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2020, 8, e16381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobe, B.; Morgan, D.L. Assessing the Effectiveness of Video-Based Interviewing: A Systematic Comparison of Video-Conferencing Based Dyadic Interviews and Focus Groups. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2021, 24, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agić, Z.; Đurović, V.; Išaretović, S. Experiences of Students and Professors in Online Teaching during Pandemics. EMC Rev.-Časopis Za Ekon.-APEIRON 2022, 23, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, H.; Ivanova, J.; Wilczewski, H.; Ong, T.; Ross, N.; Bailey, A.; Cummins, M.; Barerra, J.; Bunnell, B.; Welch, B. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap): A Survey of User Preferences and Needs for Health Data Collection. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 12, e49785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, H.; Mondal, S.; Ghosal, T.; Mondal, S. Using Google Forms for Medical Survey: A Technical Note. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Physiol. 2019, 5, 216–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurulhuda, J.; Sharifah, A.M.R.; Azzuhana, R.; NurZarifah, H.; Khairil, A.A.K. Vehicle Kilometer Travelled by Online Survey. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2020, 10, 1131–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J. The Need for Improved Ethics Guidelines in a Changing Research Landscape. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2019, 115, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepperd, J.A.; Pogge, G.; Hunleth, J.M.; Ruiz, S.; Waters, E.A. Guidelines for Conducting Virtual Cognitive Interviews During a Pandemic. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e25173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satria Nugraha, Y.; Rusdjijati, R.; Abdul Hakim, H.; Edhita Praja, C.B.; Wicaksono, M.P.; Praditama, D.A. Urgensi Rancangan Undang-Undang Perlindungan Pekerja Informal: Analisis Hak Atas Kesehatan. Fundam. J. Ilm. Huk. 2023, 12, 334–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garson, G.D. Partial Least Squares: Regression and Structural Equation Models; Statistical Publishing Associates: Asheboro, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Taherdoost, H. Validity and Reliability of the Research Instrument; How to Test the Validation of a Questionnaire/Survey in a Research. SSRN Electron. J. 2016, 5, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.C.; Gabbe, S.G.; Kemper, K.J.; Mahan, J.D.; Cheavens, J.S.; Moffatt-Bruce, S.D. Training on Mind-Body Skills: Feasibility and Effects on Physician Mindfulness, Compassion, and Associated Effects on Stress, Burnout, and Clinical Outcomes. J. Posit. Psychol. 2020, 15, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. The Results of PLS-SEM Article Information. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2018, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S. Health Care in Aged Population: A Global Public Health Challenge. J. Med. 2019, 20, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sixsmith, A. Technology and the Challenge of Aging. In Technologies for Active Aging; Sixsmith, A., Gutman, G., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inokuchi, R.; Hanari, K.; Shimada, K.; Iwagami, M.; Sakamoto, A.; Sun, Y.; Mayers, T.; Sugiyama, T.; Tamiya, N. Barriers to and Facilitators of Advance Care Planning Implementation for Medical Staff after the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Overview of Reviews. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e075969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardhiah, A.; Farisha, N.; Yuan, W.P.; Tony, F.N. Investigating the Influence of Perceived Ease of Use and Perceived Usefulness on Housekeeping Technology Intention to Use. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 12, 1306–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQueen, A.; Kreuter, M.W. Women’s Cognitive and Affective Reactions to Breast Cancer Survivor Stories: A Structural Equation Analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010, 81, S15–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheeran, P.; Harris, P.R.; Epton, T. Does Heightening Risk Appraisals Change People’s Intentions and Behavior? A Meta-Analysis of Experimental Studies. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 511–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumaedi, S.; Bakti, I.G.M.Y.; Rakhmawati, T.; Widianti, T.; Astrini, N.J.; Damayanti, S.; Massijaya, M.A.; Jati, R.K. Factors Influencing Intention to Follow the “Stay at Home” Policy during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Health Gov. 2020, 26, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Mannan, M.; Rahman, M.M. The Intention to Quit Smoking: The Impact of Susceptibility, Self-Efficacy, Social Norms and Emotional Intelligence Embedded Model. Health Educ. 2018, 118, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calisir, F.; Calisir, F. The Relation of Interface Usability Characteristics, Perceived Usefulness, and Perceived Ease of Use to End-User Satisfaction with Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) Systems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2004, 20, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Country | ||

| Indonesia | 238 | 50.4 |

| Thailand | 234 | 49.5 |

| Age (Years) | ||

| 30–35 | 112 | 25.9 |

| 36–40 | 156 | 35.9 |

| 41–45 | 101 | 23.3 |

| 46–50 | 52 | 12.0 |

| 51–55 | 35 | 8.1 |

| 56–60 | 16 | 3.7 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 176 | 37.3 |

| Female | 296 | 62.7 |

| Education Level | ||

| Non-Educated | 12 | 2.5 |

| Higher Education/College | 77 | 16.3 |

| Diploma | 123 | 26.1 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 199 | 42.2 |

| Master’s Degree | 54 | 11.4 |

| Doctoral | 7 | 1.5 |

| Occupation | ||

| No Occupation | 6 | 1.3 |

| Private Sector Employee | 113 | 23.9 |

| Government Employee | 143 | 30.3 |

| Entrepreneur/Self-Employed | 158 | 33.5 |

| Student | 31 | 4.63 |

| Healthcare Professional | 21 | 4.4 |

| Indicator | Questions | Outer Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha (alpha) | Composite Reliability (rhoC) | AVE | VIF | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PU | Perceived usefulness | 0.653 | 0.812 | 0.591 | |||

| PU1 | Using the health care application improved my everyday life quality | 0.771 | 1.288 | Valid | |||

| PU2 | Using the health care application enhanced my effectiveness on taking care of myself and my family | 0.772 | 1.283 | Valid | |||

| PU3 | I found the health care application useful in my everyday life | 0.762 | 1.253 | Valid | |||

| PEOU | Perceived ease of use | 0.699 | 0.832 | 0.624 | |||

| PEOU1 | Learning to use the health care application is easy for me | 0.806 | 1.391 | Valid | |||

| PEOU2 | My interaction with the health care application has been understandable | 0.815 | 1.408 | Valid | |||

| PEOU3 | It is easy to become skillful at using the health care application | 0.746 | 1.303 | Valid | |||

| PSU | Perceived susceptibility | 0.666 | 0.817 | 0.599 | |||

| PSU1 | It is likely that I will get a chance to have a palliative care giver. | 0.822 | 1.345 | Valid | |||

| PSU2 | I feel knowledgeable about my risk of getting a chance to have a palliative care giver | 0.801 | 1.382 | Valid | |||

| PSU3 | Perceived chances of contracting with some serious disease? | 0.692 | 1.217 | Valid | |||

| PSE | Perceived severity | 0.733 | 0.849 | 0.652 | |||

| PSE1 | I feel that without this advance care plan application I won’t be able to return to my normal life because of the worry. | 0.807 | 1.452 | Valid | |||

| PSE2 | I feel that if I do not use this application, I will have anything to precaution. | 0.828 | 1.530 | Valid | |||

| PSE3 | I will have to pay more for medical bills, if I have nothing to warn me with health condition. | 0.786 | 1.389 | Valid | |||

| HM | Health motivation | 0.73 | 0.844 | 0.645 | |||

| HM1 | Regularly the healthy behaviors have become the fundamental of my habits. | 0.863 | 1.450 | Valid | |||

| HM2 | I believe it’s a good thing I can do to feel better about myself in general. | 0.778 | 1.425 | Valid | |||

| HM3 | I think there are more important things to do than staying healthy. | 0.765 | 1.440 | Valid | |||

| PBE | Perceived benefits | 0.709 | 0.837 | 0.632 | |||

| PBE1 | The ACP application makes me feel safe and secure of health condition. | 0.839 | 1.443 | Valid | |||

| PBE2 | This service will facilitate the society. | 0.773 | 1.366 | Valid | |||

| PBE3 | This service will reduce the severity of health conditions. | 0.771 | 1.361 | Valid | |||

| PBA | Perceived barriers | 0.828 | 0.896 | 0.742 | |||

| PBA1 | This service will be difficult for me to use if available only on smartphones/tablets. | 0.896 | 2.074 | Valid | |||

| PBA2 | This service will be difficult for me to access if offered exclusively in English. | 0.885 | 1.991 | Valid | |||

| PBA3 | I feel unsecure to disclose my personal data. | 0.799 | 1.707 | Valid | |||

| BI | Behavioral intention or cues to action | 0.734 | 0.850 | 0.653 | |||

| BI1 | I am interested and expect to use this ACP application in the future. | 0.801 | 1.416 | Valid | |||

| BI2 | I plan to use this ACP application in the future. | 0.815 | 1.467 | Valid | |||

| BI3 | I predict I will use this ACP application in the future. | 0.808 | 1.477 | Valid |

| Hypothesis | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | Code | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived usefulness -> Behavioral Intention | 0.189 | 0.181 | 0.053 | 3.584 | 0.000 *** | H1 | Significant |

| Perceived ease of use -> Behavioral Intention | 0.150 | 0.154 | 0.064 | 2.319 | 0.010 ** | H2 | Significant |

| Perceived susceptibility -> Behavioral Intention | 0.153 | 0.152 | 0.056 | 2.737 | 0.003 ** | H3 | Significant |

| Perceived severity -> Behavioral Intention | 0.105 | 0.105 | 0.054 | 1.931 | 0.027 * | H4 | Significant |

| Health Motivation -> Behavioral Intention | 0.073 | 0.075 | 0.057 | 1.283 | 0.100 | H5 | Not Significant |

| Perceived Benefits -> Behavioral Intention | 0.241 | 0.240 | 0.062 | 3.866 | 0.000 *** | H6 | Significant |

| Perceived Barriers -> Behavioral Intention | 0.034 | 0.036 | 0.031 | 1.107 | 0.134 | H7 | Not Significant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Futri, I.; Ketkaew, C.; Naruetharadhol, P. Influential Factors Affecting the Intention to Utilize Advance Care Plans (ACPs) in Thailand and Indonesia. Societies 2024, 14, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14080134

Futri I, Ketkaew C, Naruetharadhol P. Influential Factors Affecting the Intention to Utilize Advance Care Plans (ACPs) in Thailand and Indonesia. Societies. 2024; 14(8):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14080134

Chicago/Turabian StyleFutri, Irianna, Chavis Ketkaew, and Phaninee Naruetharadhol. 2024. "Influential Factors Affecting the Intention to Utilize Advance Care Plans (ACPs) in Thailand and Indonesia" Societies 14, no. 8: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14080134