1. Introduction

Evolution of mobile technologies influences all public areas in both developing and developed countries. Rapid changes in marketing of mobile technologies have turned to the creation of new abilities in both e-government and e-participation. Connectivity of mobile phone and internet has developed the phenomenon of m-government that fostered transformation of public services [

1]. Goyal and Purohit [

1], Trimi and Sheng [

2], Almarashdeh and Alsmadi [

3], Mpinganjira [

4] revealed many advantages of mobile government (later in this paper—MGov) such as better and faster availability, more personalization and democracy, real in time dialog, cost effectiveness and simplicity, corruption prevention, emergency response, efficiency, etc.

MGov influences improvement of e-government and requires some specific adaptation or rebuilding to mobile applications such as website design, layout, content, etc. The mobile communication is used as a complementary perspective to explain user acceptance of MGov services [

5].

MGov user base is comprised of all classes of people as it requires little technological knowledge [

6]. MGov creates and/or extents the ability for remote citizens to accept public services and public information, as well as functioning to solve their everyday life problems within their municipality or even nationally. New mobile applications lead public servants as well as citizens to learn and innovate in order to participate in a public life.

Local governors, while receiving on time announcements on important local issues (i.e., rubbish, road accidents, etc.) from citizens, may react faster or in other words, may increase the quality of public services and thus achieve higher quality in the particular living environment. This active collaboration may develop and strengthen local governance (de facto) which is meant as a prerequisite for happier society. Therefore, we argue that MGov would play a significant role (especially on the level of municipal governance) in bringing a benefit to both citizens and local public authorities.

In agreement with Al Thunibat, Zin and Sahari) who state that “services should be delivered in ways with which the public is already familiar and/or in which users are actively engaged“ [

7] (p. 104) we argue that MGov is closely related to learning (or gaining the new knowledge) that leads to the changes in individual, social and public attitudes, understanding and behaviour. It means that the learning (or gaining the knowledge) about MGov should occur in all levels of the municipal structure.

Most papers on MGov are grounded on the behaviour theory and mostly analyse the issues of attitudes and behaviours of the general public, individuals and society [

4,

5]. Therefore, Al-Hubaishi, Ahmad and Hussain [

8] emphasize the role of public authorities, stating that the primary responsibility of government is both to deliver essential community services and to provide information access to citizens while using technological tools.

We argue that it is not enough for only the society members to be aware of mobile applications. Contemporary IT knowledge and skills as well as the attitudes, understanding and behaviour of public authorities seem to be much more important for effective and high-quality government processes. In other words, we argue that public leaders should be more concerned about developing MGov.

Shareef et al., [

6] state that in many countries “public-service systems enjoy a monopoly and suffer no competitive pressure to achieve efficiency and effectiveness”. However, on the contrary, the democratic world with its directives makes changes to the social environment whilst trying to engage the private sector in public service systems for higher competitive pressure and therefore for higher service quality. Thus, for instance, in the EU (that is democratic in its origin) we probably deal with some other issues in the MGov field. Pilot research of websites of Lithuanian municipalities revealed that only 33 of all 60 have adopted their web sites to mobile applications. We perceive that the main issue of such a situation is a gap in specific knowledge and the skills of local public leaders both in mobile applications and MGov. It is worth noting that Lithuania stands on the leading position in EU considering the IT network and speed of the internet.

Therefore, we face the question: how do we foster the knowledge about (and improve the skills regarding) mobile applications among the public leaders for more effective MGov? That would lead to more active m-participation.

Hung, Chan and Kuo [

5], Kotler, Kartajaya and Setiawan [

9] emphasize social marketing as a useful tool for correction or change of societal behaviours and attitudes towards innovations and solution of modern problems. They propose applying marketing communication to service acceptance.

Three levels of social marketing are defined [

10] to be used for the different stakeholders.

Downstream social marketing is directed to the individuals,

mid-stream social marketing—to the social groups and

upstream social marketing—to the decision makers, politics and administrators. While agreeing with the above statements, we argue that upstream social marketing would firstly foster local public authorities to gain the specific knowledge and skills and secondly to influence the employment of mobile applications for MGov in municipalities, as these locally governed territories are mostly interrelated with the concept of governance.

Thus, in our paper, we revealed the benefit of the MGov for the local upstream audience and proposed the theoretical model of upstream social marketing for the successful MGov on a municipal level. The model distinguishes two important aspects: (i) possible external marketers (those from IT business) and (ii) marketing content (motivating theses) categorized by 7P marketing mix (consisting of seven P elements: Product, Price, Place or physical evidence, Promotion, Participants or people, Processes, Political power).

2. Materials and Methods

Mobile government as a higher level of e-government has already found its place in the field of research interest of contemporary public administration (see authors cited in this paper), but following interdisciplinarity challenges, we also decided to pay our attention to the discourse of social marketing that seems to have an increasing interest among the researchers of public sector (see authors cited in this paper).

Our study contributes to the upstream social marketing by building on the new proposals for mobile government. The choice of the research methodology is based on a pluralist position. E-government is undergoing a transition period, the vegetational existence of e-delivery of public services per se may be questioned. Thus, a study on modelling implementation of MGov in post-industrial society provides the possibility tof identifing the following holistic features:

Topical, stable, and conjunctural;

Universal and local;

Specific and common, both empirical and normative perspectives in the context of the upstream social marketing.

Various aspects of MGov have been widely discussed in Western democracies, except models of implementing MGov in the upstream social marketing context. The aims of the article are new, topical, and significant for the development of public administration behavioural theory and e-government culture.

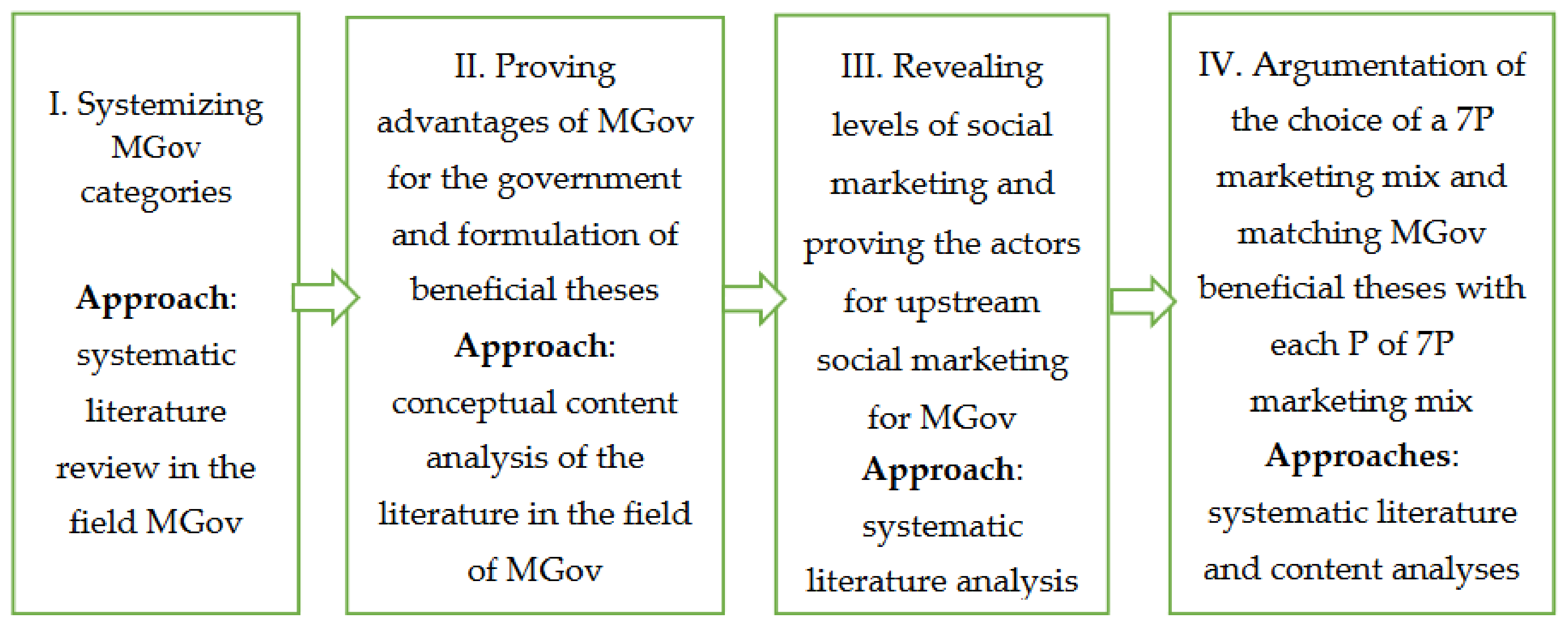

A systematic literature review in the fields of mobile governance and social marketing was used in this paper. We analysed specific papers on these two topics as there are no studies combining both discourses.

In the first subsection, we firstly proposed categories of mobile governance (systemized categories) and after that defined its benefit, linking specific advantages to each category. In the second subsection, we revealed important aspects of social marketing: goals; marketing levels for different stakeholders. We also explained our choice of 7 P marketing mix for service (including public services) marketing.

The aim of our research is to clarify related, adequate, and optimal models of implementing MGov. The research is based on three traditional challenges: to critically evaluate the past, to qualify the present, and to foresee the norms and the perspective. In order to reach this aim, the method of logical clasification and distribution was applied and the following criterias were taken into consideration: the aspect of analogical m-government destiny, the aspect of mature m-government experience, and the aspect of technological and administrative activity and historical and topical potential.

Mid-stream and upstream marketing levels have been neglected by social marketers in general [

10] therefore, we predicted a similar situation in the MGov marketing field.

We decided to shed light on the upstream social marketing for MGov on the municipal level (as municipalities are the most important substances for the welfare of society) and predict the following:

Hypothesis 1. For success of MGov its benefits need to be aware not only for individuals or society members (down and mid-stream audiences), but also for policy formers and other decision makers (upstream audience).

Hypothesis 2. Upstream social marketing is important and should be used to foster MGov among the upstream audience on municipal level.

Hypothesis 3. Marketers of IT business may play a role as upstream social marketers while fostering MGov with a categorized thesis matched to 7P marketing mix.

After the pilot literature review, we found out that the benefit of MGov was revealed only for the downstream audience. There is a lack of research specific to the upstream audience (or the government bodies) who play the primary role in the construction of the public governance. Therefore, we used the literature analysis to find any definitions or inscriptions concerning the advantages for a government. All collected data was grouped (or systemized) into specific categories, and specific theses proving the theoretical benefit for the government bodies were related to an appropriate category of MGov. An approach of conceptual content analysis was also used to distract these advantages as beneficial theses. These theses later were matched with the appropriate P of 7P marketing mix.

We not only constructed the theoretical model for the fostering MGov on the local upstream level but also proposed both responsible actors and possible marketing content (theses) based on the scientific arguments. The marketing content for promoting the MGov innovation was constructed on the frame of 7P marketing mix that is very appropriate for all services including those of public sector. Characteristics of each 7P dimension as well as the marketing theses were constructed on the analysed theories and systemized in relation to the concept of benefits of MGov. The theses we have proposed emphasize the exceptional benefit of MGov for upstream audience (see

Figure 1).

3. Results

3.1. Mobile Government for More Effective E-Government

The scientists analysing the contemporary trends of m-government development through the world have identified a number of advantages in this area. Most papers researched the phenomenon from the citizens’ perspective, emphasizing change of their behaviours and attitudes towards MGov. However, what is less explored by researchers is the MGov perspective from the point of view of the government. What are the advantages of the MGov for a government as a whole? Why is it important for the government to start using MGov tools? In this paper, we are looking for new meanings, attitudes, values and emotions as engines for changes, sharing experiences of effective MGov for a government.

Analysis of scientific literature allowed us to admit that most authors do not differentiate the m-government advantages into categories. However, our analysis proposed the possibility of categorizing them into function-driven advantages of m-government for the government. Here we highlight and further describe interrelated major function-driven advantages: (i) mobility of government, (ii) carrots, sticks and sermons, (iii) encouraging coproduction, (iv) digital administration, (v) non-constrained infrastructure.

Mobility of government. Since the beginning of the New Public Management, it has been argued that governments should deliver public services by using flexible, transparent, customer-oriented, access free, managerial approaches (contracting-out; public services one-stop-shops). Indeed, mobile technologies allow the government to provide the services 24/7, battery-power permitting, with an internet-enabled device [

11,

12,

13]. MGov creates conditions to move the service together with the customer, on the contrary, in the past, the service points moved to reach the clients (remote workplaces; service centres in rural areas, etc.).

Carrots, Sticks and Sermons. According to Vedung [

14] a government has capacity to choose among three public policy instruments in the implementation of the policy: economic means (carrots); regulations (sticks) and information (sermons). Indeed, the mobile government may enjoy the possibility of using all three-policy instruments too. Carrots, in the case of m-government, can be understood as

economic means in kind that according to Vedung [

14] are perceived as provision of goods and service. The capacity to provide services through smart phone applications and GPS service has been explained by many researchers in the field [

2,

12,

15,

16]. The regulatory power of m-government is interlinked with information provision to the residents. Different government programmes may be equipped with opportunities to spread information about the programme existence and features through the smart phones. That allows the government to save time while passing information [

1]. On one hand, m-government can effectively communicate with residents through their smart phones in case of urgent messages, crisis management, educating and informing them about benefits [

17,

18]. On the other hand, the residents always have their smartphones close to them. Therefore MGov can “keep in touch” with residents by providing on time information regarding different regulations, describing required actions or appropriate behaviours of individuals by being accountable, responsive, transparent and even

crazy like Estonia [

19,

20]. In other words, the government is now able to correct or influence the behaviour and attitude of the society very quickly. Even the trust in technology is growing [

21].

Encouraging co-production. Government has financial resources, power and influence for encouraging co-production of the public services. According to Ostrom [

22], co-production is a process in which input (staff, infrastructure, resources) is used for the production/provision of goods and services. This process involves individuals who are not public employees. Ostrom [

22] notes that all public goods and services are potentially provided through regular service providers and customers. Ingrams argues that m-government “

can boost coproduction and citizens participation” [

13] (p. 158), that, according to some sources [

1,

2,

15,

23], allows it to become cost-effective by saving resources on data gathering, sending stamped letters, decreases data entry errors, and provides faster and less erroneous processing of data. Citizens’ engagement in the delivery of the public services through the MGov makes public servants’ everyday work more effective.

Digital administration. Authors depict MGov as the core of the

new digital administration of m-government. Szabo [

12] provides an example that there is no need for the new digital administration to sit daily in the office. According to the author: “

even a committee meeting can be held either on a train with mobile devices” [

12] (p. 73). However, Alraja [

24] (with no clarification of what may be the reason: age, experience, organizational culture, etc.) opposes that social influence from the family, friends, partners, etc. may impact administrators’ decisions concerning the adoption of digital tools. However most authors [

13,

16,

23,

25] argue, that coordination of data and branches, communication between different layers of government and internal processes become better due to MGov potential. Direct access to databases, protocols, registers [

15] (that was challenging even in the time of the diffusion of citizen services centres development) become available in the case of better delivering of the public services.

Non-constrained infrastructure. One of the issues most often raised by researchers is the infrastructure constraints for the countries with poor wired infrastructure [

2,

16]. The investment into the MGov serves for better connectivity (i.e., wireless) that creates more equal conditions to provide public services and allows them to reach remoted territories [

2]. Delivery of e-public services through mobile devices eliminates access restrictions and ensures services that are demand-driven.

The definitions above may be systemized thematically as the possible benefit of MGov (see

Table 1). The government in general and the municipal government in particular (as having the closest engagement with society) somehow need to be informed about this benefit.

3.2. The Main Aspects of Social Marketing for MGov

Kotler is famous as an originator of marketing theory who later also developed a phenomenon of social marketing. According to the marketing theory, the main goal of business marketing is to increase business market or to sell more goods and services in order to fulfil interests of shareholders and consumers. Therefore the authors [

26] point out that businesses use the marketing technics to benefit a company and its stakeholders.

Social marketing in opposition to business marketing develops fundamental concepts to solve social problems [

26]. This kind of marketing is directed at the welfare of society while changing or improving social environment.

The discourse of social marketing has been analysed in various papers [

10,

27]. The authors revealed that social marketing has a profound positive impact on various social issues: i.e., public health, injury prevention, environment, community involvement, financial well-being [

28], public infrastructure, physical activity, water quality, substance misuse, use of non-custodial sentences [

29], etc.

The authors argue that social marketing is more difficult than commercial marketing. For instance, provided (marketed) goods look cool and tasty for consumers, thus satisfying their needs. While efforts to make changes in the consumption habits or changes in the attitudes towards harmful, addictive behaviour (social marketing) is usually a big challenge. However, there is the rare individual who is eager to consciously and voluntary to give up an addictive behaviour, change to a comfortable lifestyle, establish new habits, learn a new skill, etc.

Lee and Kotler systemized definitions of social marketing [

28]. These definitions revealed that the

phenomenon contains of many characteristics. It may be charactered as being the sustained over time process/activity, planned approach or a way to use commercial marketing strategies, marketing principles and techniques for social innovations or modern solutions that may overgo the barriers and improve social well-being. Social marketing is used by governments and non-profit organizations in order to engage and empower the individuals and target audiences for the positive changes.

Despite the originating roots of social marketing in early 1970s, the term is still “a mystery to most” [

28] (p. 2). Thus, we decided to emphasise some important aspects of this phenomenon.

Examples of goals of social marketing in various papers allow them to be divided into two main groups related to the behaviour (voluntary or involuntary) change: (i) goals for fostering a new type of positive behaviour for saving the lives, preventing health issues, etc.; (ii) goals for stopping harmful behaviour that leads to negative outcomes for the individuals or even society (see

Table 2). In many cases, social marketing stands against and tries to withstand business marketing in order to either release or re-influence the behaviour and attitude both of individuals and society that have been formed under the influence of business marketing.

Dibb and Carrigan [

10], Khajeh et.al, [

26], Lee and Kotler [

28], Gordon [

29] differentiate target audiences for practicing the social marketing into three levels: (i) downstream marketing audience; (ii) mid-stream marketing audience and (iii) upstream marketing audience. The authors point out different influence goals associated with these audiences. The selection of a target audience is based on different criteria including prevalence of the social problem, ability to reach the audience, readiness for change and other factors (see

Table 3).

According to Lee and Kotler [

28], Gordon [

29] in most cases, social marketing principles and techniques are used by those who are responsible for influencing public policy, rules, behaviours or to improve public health, prevent injuries, etc. In other words, it is mostly used (or intended to be used) by the government, administrators or other decision makers (

upstream audience), who apply social marketing directly to the individuals (

downstream audience) or social groups (mid-stream marketing). However, the authors also state that these upstream people are not social marketers by their profession, or they even may not have appropriate knowledge on the specific marketing topic. For instance, Al -Hubaishi, Ahmad and Hussain [

8] remind us that the primary responsibility of government is both to deliver essential community services and to provide information access to citizens while using technological tools. Although, these authorities (or some of them) may not be aware of the principles, adaptation or benefit of particular technological tools (MGov in our case). Therefore, we recognize a lack of guidance for successful upstream social marketing, and a more systemic approach that could alter the structural environment in which pro social change is sought [

10,

29].

Due these arguments, we agree with Khajeh, Dabestani and Fathi [

26], that social marketing should focus much more on an upstream audience in an attempt to influence policy formers, public administrators, political leaders and other public decision makers. Thus, we argue that in the case of MGov, upstream marketing, principles and techniques firstly should be focused on changing understanding, attitudes and behaviours of those in front lines.

We agree that this indeed should be challenging, as according to Gordon [

27] upstream social marketing not only involves different techniques but researchers also “may be reluctant to enter the socio-political arena”. To follow social marketing relations to other scientific fields [

29], we would point out that for the effective outcome of upstream social marketing for MGov, the subject might be also associated with public sector marketing (that is most often counted on to support utilization of governmental agency products and services and increase compliance with policies) and with education (because social marketers may use education as a tactic focusing on increasing awareness and understanding) as well as utilising theories and models from other disciplines. Further research should be done to practically prove these associations.

3.3. Upstream Social Marketers for Municipal MGov

Thunibat [

7] explained that services should be delivered in ways with which the public or society are already familiar (in other words the audience of all three levels should have appropriate specific knowledge). It means that individuals, social groups and public decision makers somehow need to learn about MGov or to gain the new knowledge. So, someone who already has knowledge about MGov should appear on the “government’s stage” and in some way share this knowledge, that finally could serve as a stimulant or influencer for MGov innovation in a particular territory.

Hung [

5] proposed the marketing communication to be applied to service acceptance. Several studies based on behavioural theories for MGov revealed that change of behaviour is influenced by: (i) self-efficacy (individual attitude, personal needs, etc.) and/or (ii) facilitating conditions (external influencers, marketing communication, etc.)

Kotler [

9] emphasized social marketing to be very useful for correction or change of society’s behaviour and attitude towards innovations and solution of modern problems. MGov as the contemporary innovation (or in other words higher level of e-government) requires change of the attitude of all individuals, societal groups and policy formers in order to improve co-production and corporate social responsibility that leads to public well-being. Therefore, we argue that social marketing is a very useful technique (the way or tool) for promotion and facilitation of MGov among society in a particular territory for more active m-participation.

Agreeing with Gordon, Dibb and Carrigan [

10] that social marketing is more focused on individuals, we argue that individuals have already gained enough knowledge and skills to use mobile applications and would employ them for MGov if only such ability existed. Therefore, the main concentration should be both on the upstream audience who are responsible for this innovative ability to come to the reality and the upstream social marketing that would foster their learning, knowledge and skills about MGov.

Chan [

30], Yamin and Utami [

31], Terruso [

32], Schultze [

33] and Baldersheim et.al, [

34] emphasized the importance of local authorities in the creation of public welfare. This allows us to state that governance is most effectively and efficiently applied on the municipal level. Upstream social marketing for MGov could change the attitudes and behaviours of policy formers, public decision makers towards MGov and therefore more effective local governance.

Lee and Kotler [

28] pointed out

public sector agencies (i.e., WHO

1, ministries, state sectoral agencies, departments, non-profit organizations) who usually manage social marketing and act as external professionals in a public area, but do it in a way that is not always consciously coordinated. The authors also distinguished the role of professionals working in for profit organizations in the positions of corporate philanthropy or corporate social responsibility as useful partners for social marketing.

Gordon [

29] explored the arguments from both social cognitive and social learning theories stating that the change of attitude and behaviour is governed by the immediate environment and the wider social context. In the case of MGov, the external influencers (i.e., marketers) acting on the particular territory may impact on the upstream audience of this territory accordingly, if only both sides are in good relationship or co-operation (i.e., the model of public private partnership). This model would be especially beneficial for the public sector where there is no tradition to employ social marketing in the organization’s structure.

Simasius, a mayor of Lithuanian capital Vilnius, has expressed his thoughts about the partnership in the field of smart city, explaining that experimenting in local government is a dangerous thing, but to allow businesses to experiment in the city is very important for contemporary city development [

35]. This allows us to treat businesses that are engaged in technological developments of the city, as the possible external influencers or a marketers for upstream MGov. Such businesses may, in parallel, both manage business marketing techniques and do social upstream marketing motivating upstream audience.

3.4. Content of Upstream Social Marketing for Municipal MGov

We suppose that to find the right marketing content would be a challenge for the external managers as there is no practical experience yet.

In the first part of this paper we systemized the theoretical aspects and defined the benefit of MGov (see

Table 1). Therefore, we suggest that these beneficial aspects may be transformed into motivating theses for upstream marketing (as a content) and used by external influencers (i.e., marketers) for the change of behaviour of upstream audience towards MGov. According to Gordon [

29], Jackson and Ahuja [

36] traditional marketing mix (4P: Product, Price, Place, Promotion) may not work on an upstream level: marketing principles may be applied not in a comprehensive manner. The authors insist that alternative marketing and wider use of tools (i.e., media advocacy, relationship building, stakeholder engagement, creation of motivational exchanges, promotion, public relations, etc.) are required. Agreeing with the authors, we decided to construct the marketing theses on 7Ps marketing mix that was accepted by Kotler and Keller [

36] and that is very appropriate in the field of services (see

Table 4).

4. Discussion

Mobile government has evolved due to technological innovations, and social marketing may be a very useful technique (the tool) for promotion and facilitation of that innovation among different audiences of the society in a particular territory for more active m-participation. The main concentration for the benefit of MGov should be done both on the upstream audience, who are responsible for creating this innovative ability, and the upstream social marketing.

The cities and municipalities play important roles in the context of governance, therefore the success of MGov is more aware on this level. However, policy formers and decision makers are not marketers by profession and there is sometimes no tradition to employ marketers in the public systems. Hitech business marketers then may act as external influencers or social marketers for MGov if only both sides are in good relationship or co-operation. The model of Public Private Partnership (known as PPP) may work in this case. Also, implementation of this model may have some restrictions or limitations in different countries, even democratic (e.g., Lithuania).

The social marketers also should be ready for some challenges that may occur while implementing MGov marketing strategy for political leaders and motivating them to accomplish a large social change, if to agree with Dibb and Carrigan [

10].

It has been proven in a number of studies that MGov provides many benefits for citizens. The authors argue that MGov also should become the goal for each modern government. However, for the government in general, the use of the MGov as the continuous process is usually ignored at scientific discussions. According to our findings, there are five function-driven advantages of MGov that make government flexible, transparent, customer-oriented, cost-effective, coordinating, demand-driven and powerful. Indeed, the list of benefits is not exhaustive, thus further literature analysis or even empirical researches may reveal more of them.

Social marketing in most cases stands against business marketing and serves for society wellbeing. The techniques of this marketing are used for change of attitudes and behaviours of different audiences in public life. In the context of marketing, these audiences are categorized into downstream, mid-stream and upstream audiences. Different audiences mean differentiation in social marketing content and its strategical application. Upstream social marketing is least analysed by researchers because, as they say, it is challenging to research the socio-political field and policy formers from outside the field. Nevertheless, upstream audience plays a very important role in modern public life. Therefore, open discussions among scientists or together with the political partners on how to tackle these challenges would be very useful both for further development of the theoretical topic and setting this theory into the practice of a contemporary governance. Systemic approach of upstream social marketing should be developed for the structural innovative changes of the whole social environment.

Motivation of upstream audience to foster the MGov on the territory they govern should be organized according to the marketing mix strategy based on the 7Ps. In this paper we proposed the theoretical frame for this strategy. Indeed, further empirical research is necessary to practically test the ratio of each “P” per se and in any unique territory (municipality) before developing the specific upstream social marketing mix strategy for MGov. Therefore, the lack of empirical studies may be considered both as some limitation of our study and as a challenge for the future papers.

We propose that this study is the very beginning in recognition of this interdisciplinary topic. Therefore, further studies should be directed not in one of the scientific fields (i.e., marketing, public administration, politics, digitalization, etc.) but in association with other theories and models, such as education, learning, knowledge management, social behaviour, public services, public sector marketing, etc.