Elemental Segregation and Solute Effects on Mechanical Properties and Processing of Vanadium Alloys: A Review

Abstract

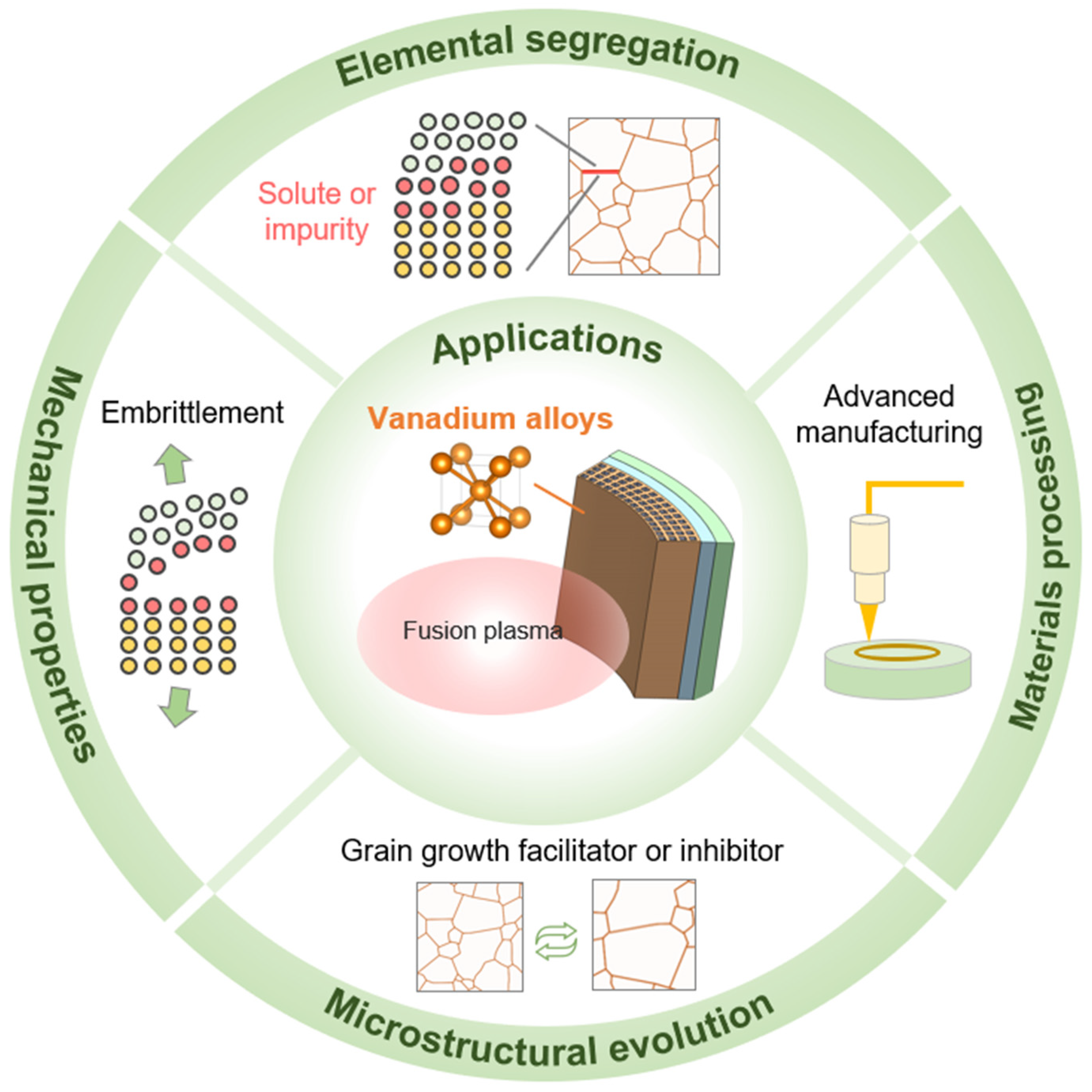

1. Introduction

2. Solute Segregation Behavior in Vanadium

2.1. Segregation to Grain Boundaries

2.2. Segregation to Sample Surfaces

2.3. Segregation to Voids

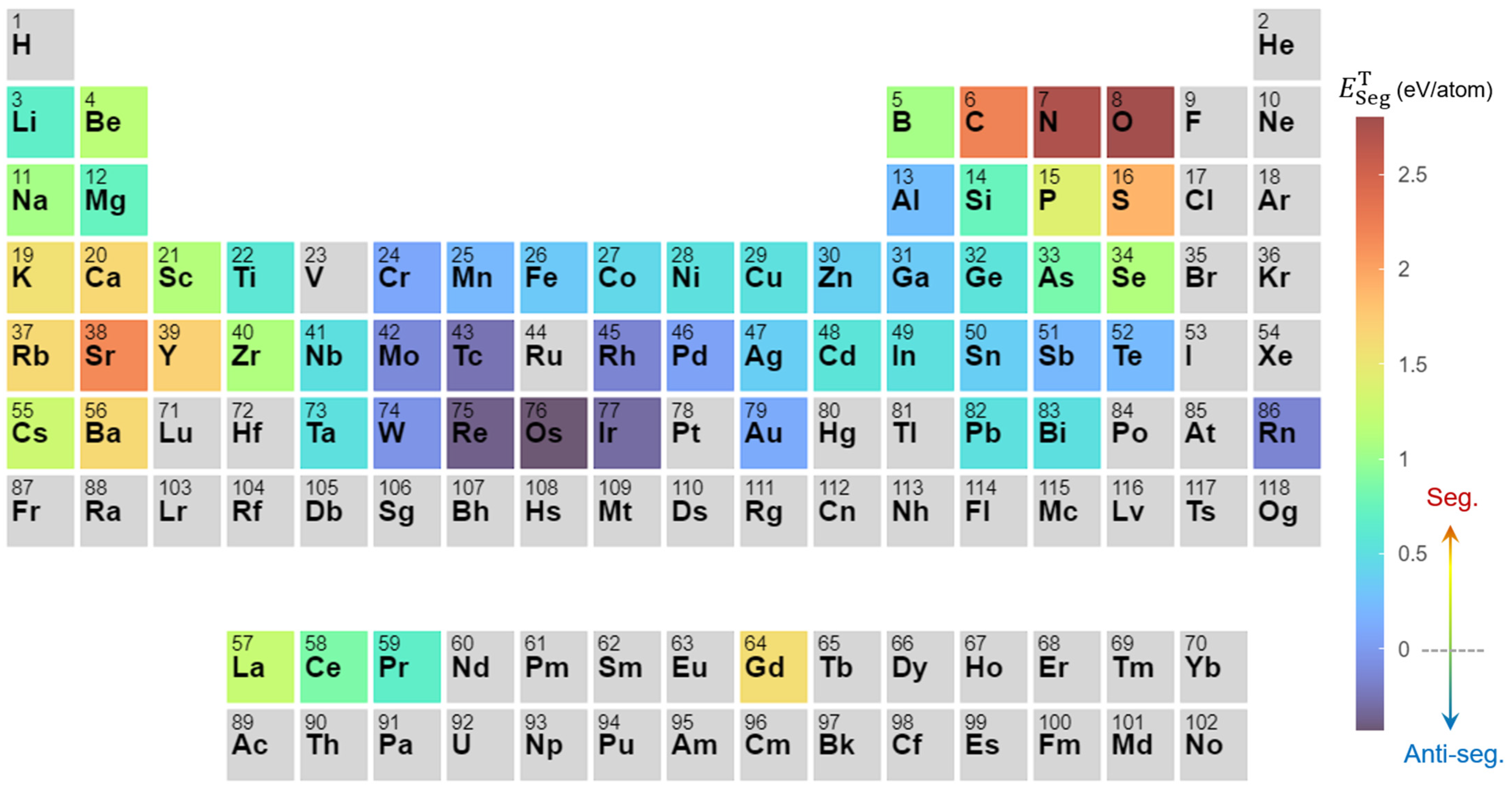

2.4. Theoretical Calculations on Segregation Behavior

3. Solute or Impurity Effects on Mechanical Behaviors of Vanadium Alloys

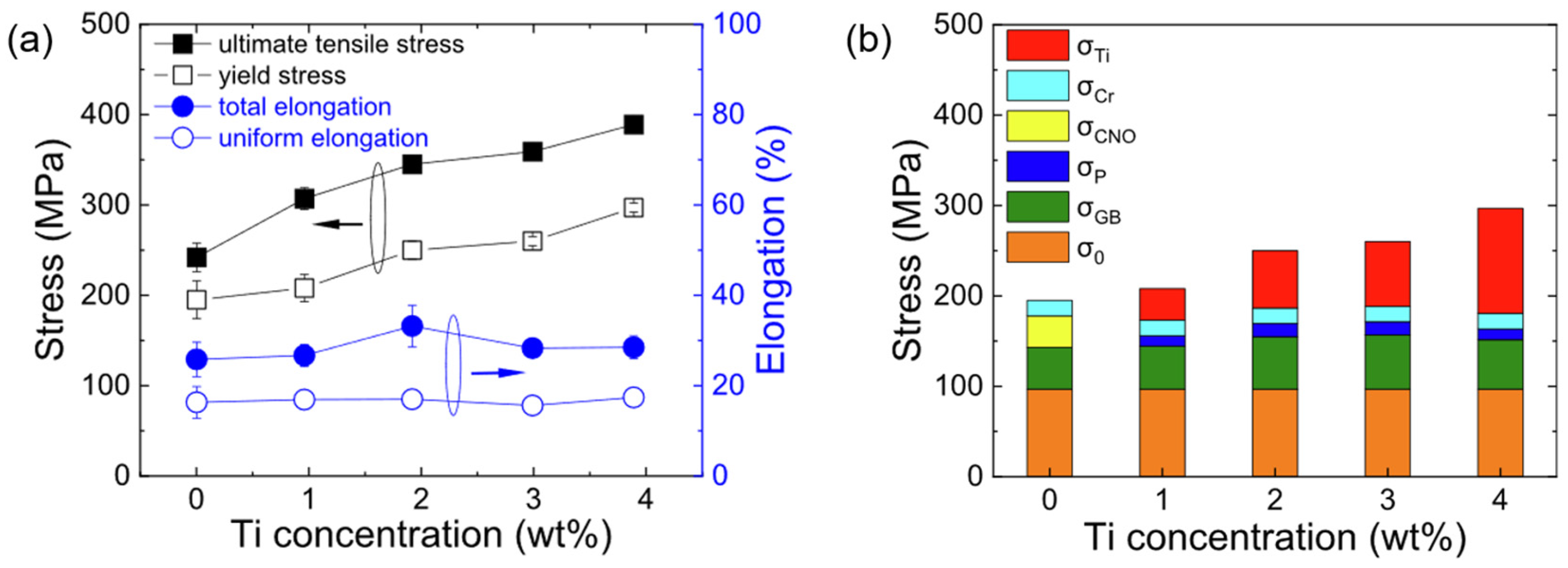

3.1. Strength and Hardness of Vanadiums Alloys

3.2. Ductility of Vanadiums Alloys

3.3. Ductile-to-Brittle Transition Behaviors in Vanadiums Alloys

3.4. Creep Properties of Vanadiums Alloys

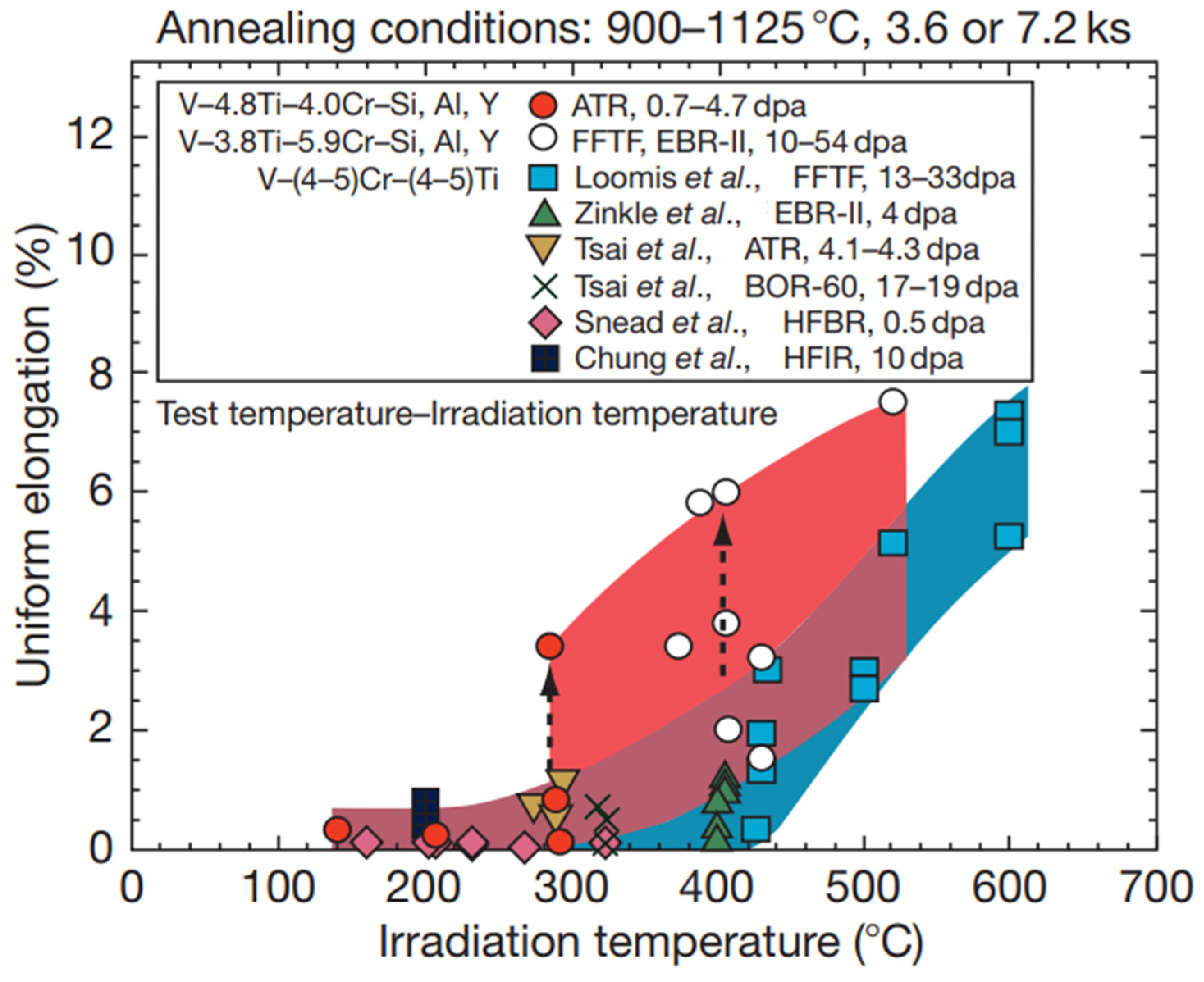

3.5. Mechanical Performance Under Irradiation

3.6. Theoretical Calculations of Solute or Impurity Effects on Mechanical Behavior of Vanadium

4. Solute or Impurity Effects on Microstructure Evolution of Vanadium Alloys

4.1. Grain Growth Inhibition

4.2. Grain Growth Acceleration

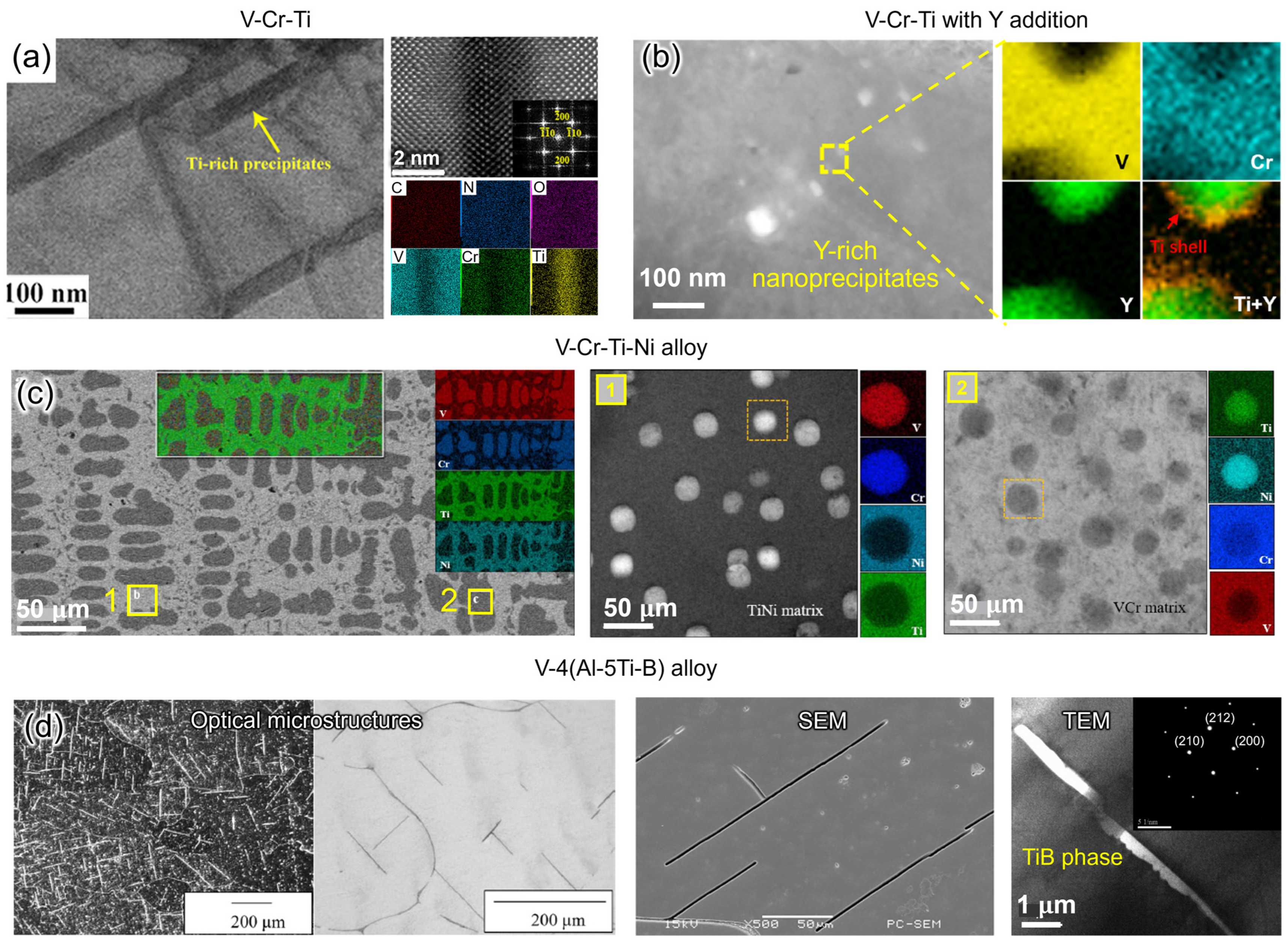

4.3. Precipitation Morphology with Solute or Impurity

5. Manufacturing of Vanadium Alloys

5.1. Conventional Manufacturing of Vanadium Alloys

5.2. Advanced Manufacturing of Vanadium Alloys

6. Future Perspectives

6.1. Experimental Studies on Vanadium Alloys

- Nanocrystalline vanadium alloys: Nanocrystalline alloys always exhibit excellent thermal stability [87,88,89]. Since YS is inversely dependent on grain sizes, developing V alloys with nanosized grains can give rise to much stronger materials. Furthermore, segregation of certain solute elements to GBs can effectively stabilize the nanocrystalline structure due to thermodynamic and/or kinetic stabilization effects. As a result, the high-temperature strength of V alloys can be significantly improved, allowing a much wider operating window for fusion reactor applications.

- Mechanical performance in extreme environments: Thermal creep performance, helium embrittlement, and irradiation embrittlement are critical issues that dictate the operational temperature limits of V-based alloys, particularly in nuclear applications. Further investigation is necessary to understand these phenomena under extreme environments, supported by the fast development of materials testing and characterization techniques, and explore the potential for expanding operational temperature ranges through the development of improved alloys.

- High-entropy (HE) vanadium alloys: Due to the large compositional space, high-entropy alloys (HEAs) appear to exhibit exceptional mechanical properties and performance [128,129,130]. Designing V-based HEAs may be a new design strategy to overcome the current issues of V alloys for fusion energy applications [30,131,132,133,134].

- Advanced manufacturing (AM) of vanadium alloys: Owing to the rapid prototyping capability of AM, there is an increase in research interests in applying AM techniques to fabricate existing or develop novel V alloys. More research is needed to investigate the resulting microstructure and performance of V alloys compared to those produced by conventional electron-beam melting and wrought approaches and optimize the best procedure.

6.2. Theoretical and Computational Studies on Vanadium Alloys

- First-principles calculations: DFT calculations are extensively used to investigate the fundamental mechanisms of solute effects on mechanical properties and their segregation behaviors. For GB segregation, most prior DFT studies calculated the ESeg of solute atoms based on highly simplified boundary structures, such as Σ3(111) twin boundary and Σ5(210) or (310) symmetric-tilt GBs [28,46,47,54,82]. However, in real polycrystalline V alloys, the majority of GBs are asymmetric and randomly distributed. Therefore, future computational research should focus on the segregation behaviors at random and general GBs, such as asymmetric boundaries.

- Atomistic simulations: Although DFT calculations can predict the segregation tendencies of solute or impurity atoms to defect regions, such as GBs, they are typically performed at zero (0) K and in the dilute limit. Moreover, the high computational cost of DFT calculations restrict simulation to small cells, containing only tens to a few hundreds of atoms. To investigate segregation behavior at more realistic conditions (e.g., 700 °C in fusion reactors), atomistic simulations using hybrid Monte Carlo/molecular dynamic (MC/MD) simulations at NVT or NPT ensembles are highly necessary for studying segregation behaviors at random GBs.

- Machine learning/artificial intelligence (ML/AI): For MD simulations, accurate interatomic potentials (IAPs) are essential. However, there are not many existing IAPs for V-related systems on the NIST website [135,136]. The classical IAPs, such as the embedded atom method (EAM) and modified EAM (MEAM), may not be sufficiently accurate for predicting materials properties of V alloys. Therefore, developing ML-based IAPs, such as SNAP, MTP, and DLP, is a promising research direction for future atomistic modeling of V alloys.

- ML/AI techniques can be also applied to predict convoluted structure–property-processing relationships in V alloys, especially in multicomponent (e.g., high-entropy) V alloys with large compositional spaces [137]. Since a high-fidelity materials database is the foundation of any ML study, developing high-throughput computational frameworks for DFT and MD simulations is necessary.

- CALPHAD and ICME approach: CALPHAD is one of the most widely used theoretical methods for alloy design. With the advances of integrated computational materials engineering (ICME) [138], the multiscale materials simulations method can be integrated to CALPHAD to accelerate the development of advanced V alloys with improved interfacial properties and decipher the structure–property-processing relationships in V alloys [139].

- Defect phase diagram: Understanding solute–defect interactions is important for designing novel V alloys with improved properties for fusion applications. A highly effective method to studying these interactions is to construct “defect phase diagrams” [140,141,142,143,144]. Similar to traditional bulk phase diagrams, defect states can also be mapped as a function of bulk composition and temperatures under various thermodynamic conditions. Since defect phase diagrams are increasingly recognized as fundamental materials tools for bulk phase diagrams, developing these defect diagrams for V alloys could potentially be an emergent area for future research.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, D.L.; Chung, H.M.; Loomis, B.A.; Matsui, H.; Votinov, S.; Van Witzenburg, W. Development of vanadium-base alloys for fusion first-wall—Blanket applications. Fusion Eng. Des. 1995, 29, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muroga, T.; Chen, J.M.; Chernov, V.M.; Kurtz, R.J.; Le Flem, M. Present status of vanadium alloys for fusion applications. J. Nucl. Mater. 2014, 455, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, R.J.; Abe, K.; Chernov, V.M.; Kazakov, V.A.; Lucas, G.E.; Matsui, H.; Muroga, T.; Odette, G.R.; Smith, D.L.; Zinkle, S.J. Critical issues and current status of vanadium alloys for fusion energy applications. J. Nucl. Mater. 2000, 283–287, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muroga, T.; Nagasaka, T.; Abe, K.; Chernov, V.M.; Matsui, H.; Smith, D.L.; Xu, Z.Y.; Zinkle, S.J. Vanadium alloys—Overview and recent results. J. Nucl. Mater. 2002, 307–311, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, R.J.; Abe, K.; Chernov, V.M.; Hoelzer, D.T.; Matsui, H.; Muroga, T.; Odette, G.R. Recent progress on development of vanadium alloys for fusion. J. Nucl. Mater. 2004, 329–333, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Chernov, V.M.; Kurtz, R.J.; Muroga, T. Overview of the vanadium alloy researches for fusion reactors. J. Nucl. Mater. 2011, 417, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muroga, T. 4.12—Vanadium for Nuclear Systems. In Comprehensive Nuclear Materials; Konings, R.J.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 391–406. [Google Scholar]

- Loria, E.A. Some aspects of vanadium metallurgy in reference to nuclear reactor applications. J. Nucl. Mater. 1976, 61, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.L.; Loomis, B.A.; Diercks, D.R. Vanadium-base alloys for fusion reactor applications—A review. J. Nucl. Mater. 1985, 135, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.-B.; Zhao, J.-J.; Zou, T.-T.; Li, R.-H.; Zheng, P.-F.; Chen, J.-M. A review of solute-point defect interactions in vanadium and its alloys: First-principles modeling and simulation. Tungsten 2021, 3, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Deng, L.; Wang, L.; Tang, J.; Deng, H.; Hu, W. The effect of solutes on the precipitate/matrix interface properties in the Vanadium alloys: A first-principles study. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2018, 153, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, P.-T.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.-Z.; Yang, X.-S.; Li, J.-F.; Liu, X.; Le, G.-M.; Huang, X.-F.; Yue, G.-Z. Solution and aging behavior of precipitates in laser melting deposited V-5Cr-5Ti alloys. J. Cent. South Univ. 2021, 28, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Yang, S.; Zhang, M.; Ding, J.; Long, Y.; Wan, F. Formation and evolution of platelet-like Ti-rich precipitates in the V–4Cr–4Ti alloy. Mater. Charact. 2016, 111, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, K.; Iwasaki, M. A replica technique for extracting precipitates from neutron-irradiated or thermal-aged vanadium alloys for TEM analysis. J. Nucl. Mater. 2014, 449, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Le, G.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Xia, S.; Li, X. Grain morphologies and microstructures of laser melting deposited V-5Cr-5Ti alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 745, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameda, J.; Bloomer, T.E.; Lyu, D.Y. Grain boundary segregation of impurities in neutron irradiated and thermally aged vanadium alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 1998, 258–263, 1482–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, R.J.; Hamilton, M.L.; Li, H. Grain boundary chemistry and heat treatment effects on the ductile-to-brittle transition behavior of vanadium alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 1998, 258–263, 1375–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-T.; Tang, X.-Z.; Fan, Y.; Guo, Y.-F. The interstitial emission mechanism in a vanadium-based alloy. J. Nucl. Mater. 2020, 533, 152121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnuki, S.; Gelles, D.S.; Loomis, B.A.; Garner, F.A.; Takahashi, H. Microstructural examination of simple vanadium alloys irradiated in the FFTF/MOTA. J. Nucl. Mater. 1991, 179–181, 775–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, J.; Wiffen, F.W. Swelling and Microstructural Changes in Irradiated Vanadium Alloys. Nucl. Technol. 1976, 30, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelles, D.S.; Stubbins, J.F. Microstructural development in irradiated vanadium alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 1994, 212–215, 778–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnuki, S.; Takahashi, H.; Kinoshita, H.; Nagasaki, R. Void formation and precipitation in neutron irradiated vanadium alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 1988, 155–157, 935–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boev, A.O.; Aksyonov, D.A.; Kartamyshev, A.I.; Maksimenko, V.N.; Nelasov, I.V.; Lipnitskii, A.G. Interaction of Ti and Cr atoms with point defects in bcc vanadium: A DFT study. J. Nucl. Mater. 2017, 492, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diercks, D.R.; Loomis, B.A. Alloying and impurity effects in vanadium-base alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 1986, 141–143, 1117–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Dingreville, R.; Boyce, B.L. Computational modeling of grain boundary segregation: A review. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2024, 232, 112596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, B.A.; Kestel, B.J.; Gerber, S.B. Solute Segregation and Microstructural Evolution in Ion-Irradiated Vanadium-Base Alloys. In Radiation-Induced Changes in Microstructure: 13th International Symposium (Part I); ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1987; p. STP955-EB. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelles, D.S.; Ohnuki, S.; Loomis, B.A.; Takahashi, H.; Garner, F.A. A microstructural explanation for irradiation embrittlement of V-15Cr-5Ti. J. Nucl. Mater. 1991, 186, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.-S.; Shim, J.-H.; Jung, W.-S.; Lee, B.-J. Computational screening of alloying elements for the development of sustainable V-based hydrogen separation membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 497, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Nagasaka, T.; Tokitani, M.; Muroga, T.; Kasada, R.; Sakurai, S. Effects of titanium concentration on microstructure and mechanical properties of high-purity vanadium alloys. Mater. Des. 2022, 224, 111390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, P.J.; Carruthers, A.W.; Fellowes, J.W.; Jones, N.G.; Dawson, H.; Pickering, E.J. Towards V-based high-entropy alloys for nuclear fusion applications. Scr. Mater. 2020, 176, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhu, T.; Wang, D.; Zhang, P.; Song, Y.; Ye, F.; Wang, Q.; Jin, S.; Yu, R.; Liu, F.; et al. Effect of Vacancy Behavior on Precipitate Formation in a Reduced-Activation V−Cr−Mn Medium-Entropy Alloy. Materials 2023, 16, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.-G.; Madakashira, P.P.; Suh, J.-Y.; Han, H.N. Effect of oxygen and nitrogen on microstructure and mechanical properties of vanadium. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 675, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnuki, S.; Takahashi, H.; Shiba, K.; Hishinuma, A.; Pawel, J.E.; Garner, F.A. Influence of transmutation on microstructure, density change, and embrittlement of vanadium and vanadium alloys irradiated in HFIR. J. Nucl. Mater. 1995, 218, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeyama, T.; Takahashi, H.; Ohnuki, S. Effect of substitutional and interstitial elements on void formation in neutron-irradiated vanadium alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 1982, 108–109, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, P.R.; Wiedersich, H. Segregation of alloying elements to free surfaces during irradiation. J. Nucl. Mater. 1974, 53, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedersich, H.; Okamoto, P.R.; Lam, N.Q. A theory of radiation-induced segregation in concentrated alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 1979, 83, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, R.; Gold, R.E. Evaluation of V-15Cr-5Ti specimens after neutron irradiation in the MFE-2 experiment, Phase 1 Final Report. Westinghouse Electr. Corp. Adv. Energy Syst. Div. 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Diercks, D.R.; Smith, D.L. Alloy Development for Irradiation Performance, Progress Report: Period Ending. DOE/ER-0045/14; 1985; p. 177.

- Rehn, L.E.; Okamoto, P.R. Phase Transformations During Irradiation; Nolfi, F.V., Ed.; Applied Science Publishers: London, UK, 1983; p. 247. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, S.C.; Rehn, L.E.; Nolfi, F.V. Irradiation-induced void swelling and solute segregation in a V-ion-irradiated V-15 wt % Cr bcc alloy. J. Nucl. Mater. 1978, 78, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, K.; Kimura, A.; Matsui, H. Swelling behavior of V–Fe binary and V–Fe–Ti ternary alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 1998, 258–263, 1431–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, B.A.; Smith, D.L.; Garner, F.A. Swelling of neutron-irradiated vanadium alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 1991, 179–181, 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, K.; Tone, K.; Onitsuka, T.; Ishigami, T. Effect of Ti addition on microstructural evolution of V–Cr–Ti alloys to balance irradiation hardening with swelling suppression. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2018, 15, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, H.; Nakajima, H.; Yoshida, S. Microstructural evolution in vanadium alloys by fast neutron irradiation. J. Nucl. Mater. 1993, 205, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhang, P.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, J. First-principles study of the behavior of O, N and C impurities in vanadium solids. J. Nucl. Mater. 2013, 435, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zou, T.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, J. Effect of interstitial impurities on grain boundary cohesive strength in vanadium. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2015, 110, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Kong, X.-S.; You, Y.-W.; Liu, W.; Liu, C.S.; Chen, J.-L.; Luo, G.N. Effect of transition metal impurities on the strength of grain boundaries in vanadium. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 120, 095901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, X.; Zhao, J.; Zheng, P.; Chen, J. Atomic investigation of alloying Cr, Ti, Y additions in a grain boundary of vanadium. J. Nucl. Mater. 2016, 468, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Tang, J.; Deng, L.; Li, W.; Wang, L.; Deng, H.; Hu, W. Precipitate/vanadium interface and its strengthening on the vanadium alloys: A first-principles study. J. Nucl. Mater. 2019, 527, 151821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Meng, F.-X.; Ning, B.-Y.; Zhuang, J.; Ning, X.-J. A diffusion model for solute atoms diffusing and aggregating in nuclear structural materials*. Chin. Phys. B 2017, 26, 126601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Berbenni, S.; Medlin, D.L.; Dingreville, R. Discontinuous segregation patterning across disconnections. Acta Mater. 2023, 246, 118724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejček, P.; Hofmann, S. Entropy-Driven Grain Boundary Segregation: Prediction of the Phenomenon. Metals 2021, 11, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Medlin, D.L.; Dingreville, R. Disconnection-Mediated Transition in Segregation Structures at Twin Boundaries. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 6875–6882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Jin, S.; Yan, W. Effects of hydrogen in a vanadium grain boundary: From site occupancy to mechanical properties. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 2013, 56, 1389–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.-B.; Jin, S.; Zhang, Y.; Shu, X.-L.; Niu, L.-L. Role of helium in the sliding and mechanical properties of a vanadium grain boundary: A first-principles study. Chin. Phys. B 2014, 23, 056104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.-S.; Oh, J.-Y.; Shim, J.-H.; Suh, J.-Y.; Yoon, W.Y.; Lee, B.-J. Design of sustainable V-based hydrogen separation membranes based on grain boundary segregation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 12031–12044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zou, T.; Zhao, J.; Zheng, P.; Chen, J. Effect of helium and vacancies in a vanadium grain boundary by first-principles. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2015, 352, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ding, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, P.; Mei, X.; Huang, S.; Zhao, J. Atomistic understanding of helium behaviors at grain boundaries in vanadium. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2019, 158, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, M.; Fernandez, B.; Munoz, A.; Leguey, T.; Pareja, R.; Ballesteros, C. Titanium segregation mechanism in deformed vanadium-titanium alloys. Philos. Mag. Lett. 2001, 81, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lütjering, G.; Williams, J.C.; Gysler, A. Microstructure and mechanical properties of titanian alloys. In Microstructure and Properties of Materials; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 2000; pp. 1–77. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, W.J. Optimising mechanical properties in alpha+beta titanium alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1998, 243, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrod, D.L.; Gold, R.E. Mechanical properties of vanadium and vanadium-base alloys. Int. Met. Rev. 1980, 25, 163–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimomura, T.; Kainuma, T.; Watanabe, R. Mechanical properties of vanadium-niobium alloys. J. Less Common Met. 1978, 57, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainuma, T.; Iwao, N.; Suzuki, T.; Watanabe, R. Effects of oxygen, nitrogen and carbon additions on the mechanical properties of vanadium and V/Mo alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 1979, 80, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromm, E.; Hörz, G. Hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, and carbon in metals. Int. Met. Rev. 1980, 25, 269–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasaka, T.; Takahashi, H.; Muroga, T.; Tanabe, T.; Matsui, H. Recovery and recrystallization behavior of vanadium at various controlled nitrogen and oxygen levels. J. Nucl. Mater. 2000, 283–287, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babitzke, H.R.; Asai, G.; Kato, H. Columbium-Vanadium Alloys for Elevated Temperature Service. In High Temperature Refractory Metals, Part 2, Proceedings of the Metallurgical Society Conference, New York, NY, USA, 27–29 June 1966; Fountain, R.W., Maitz, J., Richardson, L.S., Eds.; Gordon and Breach: London, UK, 1966; p. 433. [Google Scholar]

- Rajala, B.R.; Van Thyne, R.J. The development of improved vanadium-base alloys for use at temperatures up to 1800 °F. J. Less Common Met. 1961, 3, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satou, M.; Chuto, T.; Abe, K. Improvement in post-irradiation ductility of neutron irradiated V–Ti–Cr–Si–Al–Y alloy and the role of interstitial impurities. J. Nucl. Mater. 2000, 283–287, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, C.V.; Scott, T.E. Relation between hydrogen embrittlement and the formation of hydride in the group V transition metals. Metall. Trans. 1972, 3, 1715–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eustice, A.L.; Carlson, O.N. Effect of hydrogen on the tensile properties of iodide vanadium. Trans. Met. Soc. AIME 1961, 221. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/biblio/4017193 (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- Li, H.; Hamilton, M.L.; Jones, R.H. Fusion Materials: Semiannual Progress Report for Period Ending. DOE/ER-0313/17; 1995; p. 165.

- Chung, H.M.; Loomis, B.A.; Smith, D.L. Development and testing of vanadium alloys for fusion applications. J. Nucl. Mater. 1996, 239, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Han, W.-Z. Oxygen solutes-regulated low temperature embrittlement and high temperature toughness in vanadium. Acta Mater. 2024, 273, 119983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Arsenault, R.J. The effect of oxygen on the dislocation structures in Vanadium. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1973, 12, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Jiang, S.; Wang, S.; Hui, X.; Wu, Y.; Gault, B.; Kontis, P.; et al. Enhanced strength and ductility in a high-entropy alloy via ordered oxygen complexes. Nature 2018, 563, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.M.; Loomis, B.A.; Smith, D.L. Creep properties of vanadium-base alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 1994, 212–215, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, M.; Fukumoto, K.; Matsui, H. Effects of purity on high temperature mechanical properties of vanadium alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 2004, 329–333, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, P.M.; Zinkle, S.J. Temperature dependence of the radiation damage microstructure in V–4Cr–4Ti neutron irradiated to low dose. J. Nucl. Mater. 1998, 258–263, 1414–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Fukumoto, K.-i.; Ishigami, R.; Nagasaka, T. Microstructural changes in He-irradiated V-Cr-Ti alloys with low Ti addition at 700 °C. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2024, 38, 101605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, K.-i.; Miura, S.; Kitamura, Y.; Ishigami, R.; Nagasaka, T. Correlation between Microstructural Change and Irradiation Hardening Behavior of He-Irradiated V–Cr–Ti Alloys with Low Ti Addition. Quantum Beam Sci. 2021, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Song, K.; Sun, M.; Xu, B.; Ma, H.; Lv, X. Effect of impurities on elastic properties and grain boundary strength of vanadium: A first principles study. Vacuum 2024, 225, 113252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Luo, F.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Li, F.; Xie, Z.; Lin, W.; Guo, L. Effect of yttrium content on microstructure and irradiation behavior of V-4Cr-4Ti-xY alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 2022, 559, 153480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Ma, B.; Wang, J.; Luo, L.; Wu, Y. Investigation of the Y Effect on the Microstructure Response and Radiation Hardening of PM V-4Cr-4Ti Alloys after Irradiation with D Ions. Metals 2023, 13, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, R.; Diao, S.; Wan, F.; Zhan, Q. Plasticity improvement and radiation hardening reduction of Y doped V-4Cr-4Ti alloy. J. Nucl. Mater. 2022, 560, 153508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Luo, F.; Zhang, W.; Guo, L.; Lin, W.; Yin, Z.; Cao, J. Inhibition of Ti-rich precipitates and improvement of the irradiation resistance in V-4Cr-4Ti by adding La element. J. Nucl. Mater. 2024, 591, 154927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detor, A.J.; Schuh, C.A. Grain boundary segregation, chemical ordering and stability of nanocrystalline alloys: Atomistic computer simulations in the Ni–W system. Acta Mater. 2007, 55, 4221–4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, J.M.; Hopkins, E.M.; Hattar, K.; Abdeljawad, F.; Boyce, B.L.; Dingreville, R. Stability of immiscible nanocrystalline alloys in compositional and thermal fields. Acta Mater. 2022, 226, 117620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeljawad, F.; Lu, P.; Argibay, N.; Clark, B.G.; Boyce, B.L.; Foiles, S.M. Grain boundary segregation in immiscible nanocrystalline alloys. Acta Mater. 2017, 126, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.L.; Pundt, A.; Kirchheim, R. Hydrogen-induced accelerated grain growth in vanadium. Acta Mater. 2018, 155, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Shi, X.-B.; Sun, B.-L.; Wang, H.-C.; Doland, M.; Song, G.-S. Microstructural development of vanadium–nickel crystalline alloy membranes. Rare Met. 2021, 40, 1932–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hao, L.; Shen, S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Yang, K.; Shen, T.; Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Fu, E. The effect of chemical ordering and coherent nanoprecipitates on bubble evolution in binary-phase vanadium alloys after He ion irradiation. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 212, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Feng, Z.; Xu, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, B.; Wang, Q.; Huang, H. Effect of Al-5Ti-1B refiner content on the microstructure and mechanical properties of V-x(Al-5Ti-1B) alloys for hydrogen purification. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1005, 176144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. Selective laser melting additive manufacturing of advanced nuclear materials V-6Cr-6Ti. Mater. Lett. 2017, 209, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W.R.; Smith, J.P. Fabrication of a 1200 kg ingot of V–4Cr–4Ti alloy for the DIII–D radiative divertor program. J. Nucl. Mater. 1998, 258–263, 1425–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muroga, T.; Nagasaka, T.; Iiyoshi, A.; Kawabata, A.; Sakurai, S.; Sakata, M. NIFS program for large ingot production of a V–Cr–Ti alloy. J. Nucl. Mater. 2000, 283–287, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.Y.; Chen, J.M.; Zheng, P.F.; Nagasaka, T.; Muroga, T.; Li, Z.D.; Cui, S.; Xu, Z.Y. Fabrication using electron beam melting of a V–4Cr–4Ti alloy and its thermo-mechanical strengthening study. J. Nucl. Mater. 2013, 442, S336–S340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasaka, T.; Muroga, T.; Tanaka, T.; Sagara, A.; Fukumoto, K.; Zheng, P.F.; Kurtz, R.J. High-temperature creep properties of NIFS-HEAT-2 high-purity low-activation vanadium alloy. Nucl. Fusion 2019, 59, 096046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.F.; Chen, J.M.; Nagasaka, T.; Muroga, T.; Zhao, J.J.; Xu, Z.Y.; Li, C.H.; Fu, H.Y.; Chen, H.; Duan, X.R. Effects of dispersion particle agents on the hardening of V–4Cr–4Ti alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 2014, 455, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, V.K.; Sinnaeruvadi, K. Rapid Synthesis of V-4Cr-4Ti Alloy/Composite by Field Assisted Sintering Technique. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2016, 57, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Mai, S.; Wang, D.; Song, C. Investigation into spatter behavior during selective laser melting of AISI 316L stainless steel powder. Mater. Des. 2015, 87, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmelzer, J.; Rittinghaus, S.-K.; Gruber, K.; Veit, P.; Weisheit, A.; Krüger, M. Printability and microstructural evolution of a near-eutectic three-phase V-based alloy. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 34, 101208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, K.; Biesiekierski, A.; Wen, C.; Li, Y. 5—Powder metallurgy in manufacturing of medical devices. In Metallic Biomaterials Processing and Medical Device Manufacturing; Wen, C., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 159–190. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.D.; Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Ma, T.D. Microstructure and properties of V–5Cr–5Ti alloy after hot forging. Fusion Eng. Des. 2018, 127, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Jóni, B.; Ribárik, G.; Ódor, É.; Fogarassy, Z.; Ungár, T. The Microstructure and strength of a V–5Cr–5Ti alloy processed by high pressure torsion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 758, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossbeck, M.L.; King, J.F.; Alexander, D.J.; Rice, P.M.; Goodwin, G.M. Development of techniques for welding V–Cr–Ti alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 1998, 258–263, 1369–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasaka, T.; Grossbeck, M.L.; Muroga, T.; King, J.F. Comparison of Impact Property of Japanese and US Reference Heats of V-4CR-4TI After Gas-Tungsten-ARC WELDING. Fusion Technol. 2001, 39, 664–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossbeck, M.L.; King, J.F.; Hoelzer, D.T. Impurity effects on gas tungsten arc welds in V–Cr–Ti alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 2000, 283–287, 1356–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muroga, T.; Heo, N.-J.; Nagasaka, T.; Watanabe, H.; Nishimura, A.; Shinozaki, K. Heterogeneous Precipitation and Mechanical Property Change by Heat Treatments for the Laser Weldments of V-4Cr-4Ti Alloy. Plasma Fusion Res. 2015, 10, 1405092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, N.J.; Nagasaka, T.; Muroga, T.; Nishimura, A.; Shinozaki, K.; Takeshita, N. Metallurgical and mechanical properties of laser weldment for low activation V–4Cr–4Ti alloy. Fusion Eng. Des. 2002, 61–62, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, N.-J.; Nagasaka, T.; Muroga, T.; Nishimura, A.; Shinozaki, K.; Watanabe, H. Mechanical Properties of Laser Weldment of V-4Cr-4Ti Alloy. Fusion Sci. Technol. 2003, 44, 470–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsisar, V.; Nagasaka, T.; Le Flem, M.; Yeliseyeva, O.; Konys, J.; Muroga, T. Impact properties of electron beam welds of V–4Ti–4Cr alloys NIFS-HEAT-2 and CEA-J57. Fusion Eng. Des. 2014, 89, 1633–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, L.-W.; Fu, H.-Y.; Chai, Z.-J.; Zheng, P.-F.; Wei, R.; Zhang, M.; Chen, J.-M. Dissimilar-metal bonding of a carbide-dispersion strengthened vanadium alloy for V/Li fusion blanket application. Tungsten 2020, 2, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandl, E.; Heckenberger, U.; Holzinger, V.; Buchbinder, D. Additive manufactured AlSi10Mg samples using Selective Laser Melting (SLM): Microstructure, high cycle fatigue, and fracture behavior. Mater. Des. 2012, 34, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetlizky, D.; Das, M.; Zheng, B.; Vyatskikh, A.L.; Bose, S.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Schoenung, J.M.; Lavernia, E.J.; Eliaz, N. Directed energy deposition (DED) additive manufacturing: Physical characteristics, defects, challenges and applications. Mater. Today 2021, 49, 271–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.D.; Meiners, W.; Wissenbach, K.; Poprawe, R. Laser additive manufacturing of metallic components: Materials, processes and mechanisms. Int. Mater. Rev. 2012, 57, 133–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Bai, P.; Zhao, Z. Manufacturing feasibility and forming properties of V-6Cr-Ti alloy by selective laser melting. Acta Tech. 2017, 62, 875–884. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.L.; Li, J.F. Fabrication and Analysis of Vanadium-Based Metal Powders for Selective Laser Melting. J. Miner. Mater. Charact. Eng. 2018, 6, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Deng, P.; Karadge, M.; Rebak, R.B.; Gupta, V.K.; Prorok, B.C.; Lou, X. The origin and formation of oxygen inclusions in austenitic stainless steels manufactured by laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 35, 101334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauzon, C.; Raza, A.; Hryha, E.; Forêt, P. Oxygen balance during laser powder bed fusion of Alloy 718. Mater. Des. 2021, 201, 109511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, T.; Kurishita, H.; Kobayashi, S.; Nakai, K. High temperature deformation of V-1.6Y-8.5W-(0.08, 0.15)C alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 2009, 386–388, 602–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuno, T.; Kurishita, H.; Nagasaka, T.; Nishimura, A.; Muroga, T.; Sakamoto, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Nakai, K.; Matsuo, S.; Arakawa, H. Effects of grain size on high temperature creep of fine grained, solution and dispersion hardened V–1.6Y–8W–0.8TiC. J. Nucl. Mater. 2011, 417, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurishita, H.; Oda, S.; Kobayashi, S.; Nakai, K.; Kuwabara, T.; Hasegawa, M.; Matsui, H. Effect of 2wt% Ti addition on high-temperature strength of fine-grained, particle dispersed V–Y alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 2007, 367–370, 848–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, T.; Kurishita, H.; Furuno, T.; Nagasaka, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Nakai, K.; Matsuo, S.; Arakawa, H.; Nishimura, A.; Muroga, T. Uniaxial creep behavior of nanostructured, solution and dispersion hardened V–1.4Y–7W–9Mo–0.7TiC with different grain sizes. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 528, 7843–7850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Hu, C.; Yan, Q.; Luo, J. Discovery of electrochemically induced grain boundary transitions. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q.; Hu, C.; Luo, J. Creating continuously graded microstructures with electric fields via locally altering grain boundary complexions. Mater. Today 2024, 73, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillon, O.; Gonzalez-Julian, J.; Dargatz, B.; Kessel, T.; Schierning, G.; Räthel, J.; Herrmann, M. Field-Assisted Sintering Technology/Spark Plasma Sintering: Mechanisms, Materials, and Technology Developments. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2014, 16, 830–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, E.P.; Raabe, D.; Ritchie, R.O. High-entropy alloys. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019, 4, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.F.; Wang, Q.; Lu, J.; Liu, C.T.; Yang, Y. High-entropy alloy: Challenges and prospects. Mater. Today 2016, 19, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Luo, J. Data-driven prediction of grain boundary segregation and disordering in high-entropy alloys in a 5D space. Mater. Horiz. 2022, 9, 1023–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barron, P.J.; Carruthers, A.W.; Dawson, H.; Rigby, M.T.P.; Haigh, S.; Jones, N.G.; Pickering, E.J. Phase stability of V-based multi-principal element alloys. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 38, 926–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liaw, P.K.; Zhang, Y. A Novel Low-Activation VCrFeTaxWx (x = 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 1) High-Entropy Alloys with Excellent Heat-Softening Resistance. Entropy 2018, 20, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carruthers, A.W.; Shahmir, H.; Hardwick, L.; Goodall, R.; Gandy, A.S.; Pickering, E.J. An assessment of the high-entropy alloy system VCrMnFeAlx. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 888, 161525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.L.; Li, X.W.; Sun, B.R.; Xin, S.W.; Shen, T.D. Low activation V–Fe–Cr–Mn high-entropy alloys with exceptional strength. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 860, 144243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.A.; Tavazza, F.; Trautt, Z.T.; Buarque de Macedo, R.A. Considerations for choosing and using force fields and interatomic potentials in materials science and engineering. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2013, 17, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, L.M.; Trautt, Z.T.; Becker, C.A. Evaluating variability with atomistic simulations: The effect of potential and calculation methodology on the modeling of lattice and elastic constants. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 26, 055003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, K. Machine-Learning-Based Composition Analysis of the Stability of V–Cr–Ti Alloys. J. Nucl. Eng. 2023, 4, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi Wang, W.; Li, J.; Liu, W.; Liu, Z.-K. Integrated computational materials engineering for advanced materials: A brief review. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2019, 158, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, C.; Basu, J.; Ramachandran, D.; Mohandas, E. Alloy design and microstructural evolution in V–Ti–Cr alloys. Mater. Charact. 2015, 106, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Medlin, D.L.; Dingreville, R. Stability and mobility of disconnections in solute atmospheres: Insights from interfacial defect diagrams. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2025, 134, 016202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zuo, Y.; Chen, C.; Ong, S.P.; Luo, J. Genetic algorithm-guided deep learning of grain boundary diagrams: Addressing the challenge of five degrees of freedom. Mater. Today 2020, 38, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Luo, J. First-order grain boundary transformations in Au-doped Si: Hybrid Monte Carlo and molecular dynamics simulations verified by first-principles calculations. Scr. Mater. 2019, 158, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, T.P.; Schuh, C.A. Phase and defect diagrams based on spectral grain boundary segregation: A regular solution approach. Acta Mater. 2024, 265, 119584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehranchi, A.; Zhang, S.; Zendegani, A.; Scheu, C.; Hickel, T.; Neugebauer, J. Metastable defect phase diagrams as roadmap to tailor chemically driven defect formation. Acta Mater. 2024, 277, 120145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elements | Grain Boundary (GB) | Sample Surface | Void Surface | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti |

|

| N/A | [26,27] |

| Cr |

|

|

| [19,26,27,40,44] |

| Fe |

|

|

| [26,34] |

| Ni |

|

|

| [21,26,34] |

| Nb | N/A | N/A |

| [34] |

| Mo |

|

|

| [26] |

| W |

|

|

| [19,26] |

| C |

| N/A | N/A | [17] |

| N |

| N/A | N/A | [17] |

| O |

| N/A | N/A | [17] |

| Si | N/A | N/A |

| [17] |

| P |

| N/A | N/A | [17] |

| S |

|

| N/A | [17,32,37,38] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lei, T.; Hu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X. Elemental Segregation and Solute Effects on Mechanical Properties and Processing of Vanadium Alloys: A Review. Metals 2025, 15, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15010096

Lei T, Hu C, Zhang Q, Wang X. Elemental Segregation and Solute Effects on Mechanical Properties and Processing of Vanadium Alloys: A Review. Metals. 2025; 15(1):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15010096

Chicago/Turabian StyleLei, Tianjiao, Chongze Hu, Qiaofu Zhang, and Xin Wang. 2025. "Elemental Segregation and Solute Effects on Mechanical Properties and Processing of Vanadium Alloys: A Review" Metals 15, no. 1: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15010096

APA StyleLei, T., Hu, C., Zhang, Q., & Wang, X. (2025). Elemental Segregation and Solute Effects on Mechanical Properties and Processing of Vanadium Alloys: A Review. Metals, 15(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15010096