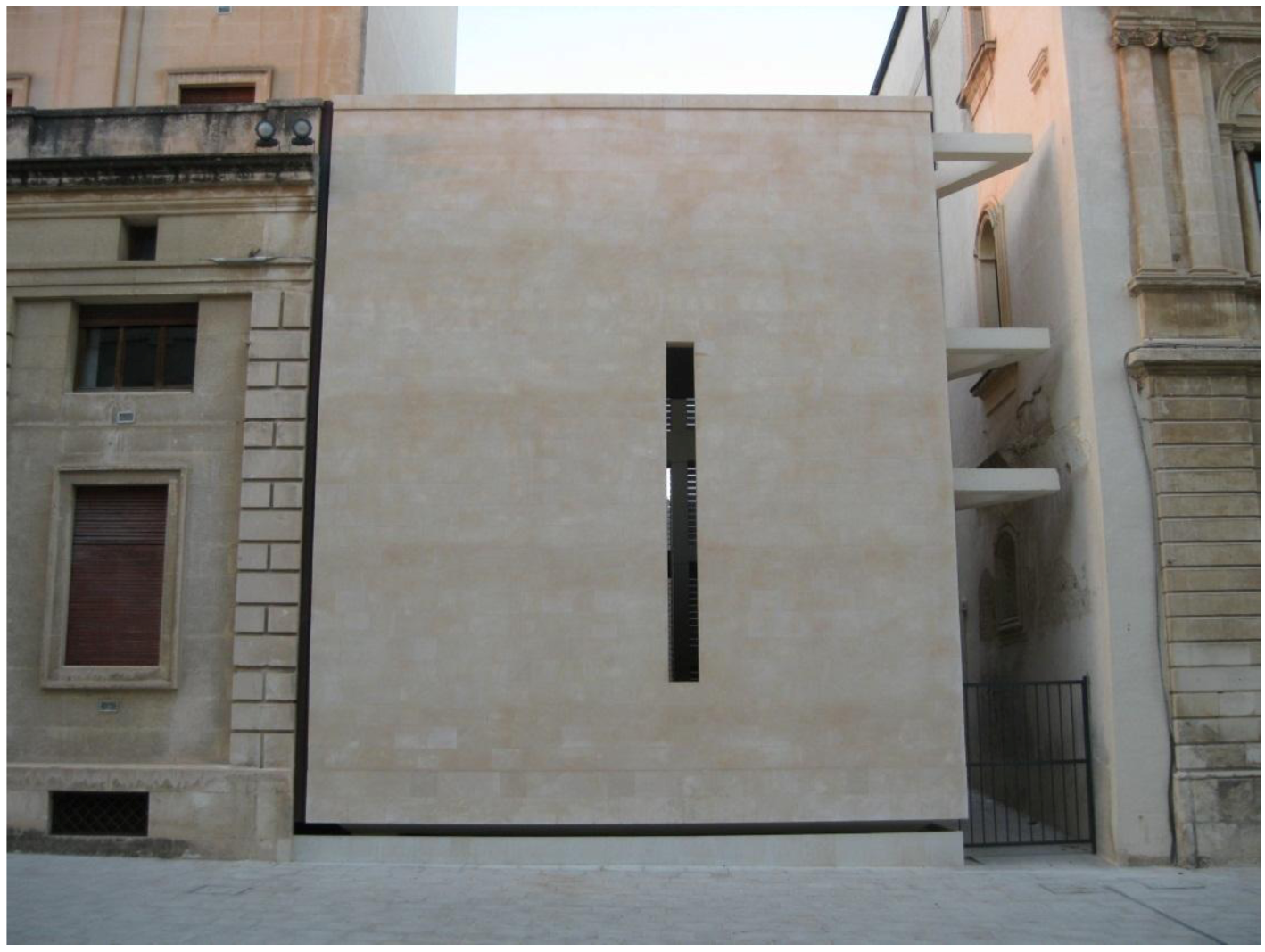

Syracuse Limestone: From the Past a Prospect for Contemporary Buildings

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Study Case

2. Experimental Section

| Sample | Address | Microclimatic zone | Taking zone | Weather conditions | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C.1.1.1 | Lungomare Alfeo, 20 | Z.1 | h = 1.50 m | sunny, hot | macroscopic fossils |

| C.1.2.1 | Passeggio Aretusa | Z.1 | h = 0.97 m | sunny, no wind | - |

| C.1.2.2 | Passeggio Aretusa | Z.1 | h = 1.80 m | sunny, no wind | thin sheet break |

| C.2.1.1 | Belvedere S. Giacomo, 3 | Z.2 | h = 2.00 m | cloudy | - |

| C.2.2.1 | Largo della Gancia, 1 | Z.2 | h = 1.30 m | sunny | - |

| C.2.3.1 | Nizza, 28 | Z.2 | h = 1.00 m | cloudy, N-E wind | - |

| C.3.1.1 | Della Maestranza, 97 | Z.3 | h = 2.20 m | sunny, no wind | surface deposit, high vehicular traffic |

| C.3.2.1 | Roma, 52 | Z.3 | h = 1.80 m | sunny, no wind | high vehicular traffic |

| C.4.1.1 | Resalibera, 6 | Z.4 | h = 1.70 m | cloudy, E-O wind | |

| C.4.3.1 | Vittorio Veneto, 64 | Z.4 | h = 1.40 m | sunny, high N-S wind | - |

| C.4.4.1 | Vittorio Veneto, 50 | Z.4 | Door jamb, ground floor | sunny, high N-S wind | - |

| C.5.1.1 | R. Lanza, 14 | Z.5 | h = 1.60 m | sunny, no wind | - |

| C.5.2.1 | Eritrea, 6 | Z.5 | Paramento h = 1.60 m | sunny, no wind | high vehicular traffic |

| Sample | Conductivity (µS) | Prevalent decay |

|---|---|---|

| C.1.1.1 | 91.8 | alveolization—surface erosion |

| C.1.2.1 | 80.7 | surface erosion |

| C.1.2.2 | 82.5 | surface erosion |

| C.2.1.1 | 68.5 | alveolization |

| C.2.2.1 | 135 | lack of parts |

| C.2.3.1 | 66.7 | lack of parts |

| C.3.1.1 | 132.6 | black crusts |

| C.3.2.1 | 109 | black crusts |

| C.4.1.1 | 85.2 | alveolization |

| C.4.3.1 | 56.4 | surface erosion |

| C.5.1.1 | 87.8 | surface erosion—lack of parts |

| C.5.2.1 | 97.6 | black crusts |

- Water absorption [7], drying [8] and capillary uptake [9] were determined by weighing the samples (three samples per lithotype) at regular intervals. The absorption coefficient, drying index, real and apparent density, saturation coefficient, degree of pore interconnectivity, and open porosity were calculated from the obtained weight values.

- Following the UNI method reported in [10], 15 test cycles of salt crystallization were performed, with a solution of 14% Na2SO4・10H2O, on 3 limestone samples per group. In every cycle, the samples were observed to evaluate progressive deterioration.

- Mechanic properties were evaluated by following standard methodologies [11].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Historic Façade Analysis

- Wackestones and packstones, a fine-grained limestone, heterogeneous for the presence of fossil, with a light cream or beige color (the so-called “Palazzolo stone”) or with yellowish color (the so-called “Noto stone”) belonging to the Formation of Palazzolo;

- Grainstone, an oolitic white limestone, fossil-rich for the 90%, with massive structure or stratified, belonging to the Formation of Carrubba Mountain;

- A greyish limestone of organic origin, very rich of shells fossils, called “lumachella”, belonging to the Formation of Carrubba Mountain;

- A compact and small-grained limestone, with heterogeneous structure, with yellowish (limestone of Melilli) or whitish color (limestone of Syracuse) belonging to the Formation of Climiti Mountains;

- An organic limestone with yellow sands (the so-called “giuggiulena stone”) extracted from the organic limestone layer (called “level Panchina”) inside the deposits of the Medium and Superior Pleistocene.

| Sample | Classification according to Folk | Classification according to Dunham | Formation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | |||

| C.1.1.1 | biomicrarenite | Wackestone | Palazzolo (2 lithotypes: Palazzolo stone and Noto stone) |

| C.1.2.1 | biomiclutite | Wackestone | |

| C.1.2.2 | biomiclutite | Wackestone | |

| C.2.1.1 | biomiclutite | Wackestone | |

| C.4.1.1 | biomicrarenite | Wackestone | |

| C.5.1.1 | biomicrarenite | Wackestone | |

| Group B | |||

| C.4.3.1 | oosparudite | Grainstone | Carrubba Mountain |

| Group C | |||

| C.4.4.1 | “Lumachella”—macroscopic identification | Carrubba Mountain | |

| Group D | |||

| C.2.3.1 | biomicrudite | Packstone | Climiti Mountains (2 lithotypes: limestone of Syracuse and limestone of Melilli) |

| C.3.1.1 | biosparudite | Grainstone | |

| C.5.2.1 | biomicrudite | Packstone | |

| Group E | |||

| C.2.2.1 | biomicrudite | Packstone | “level Panchina” |

| C.3.2.1 | biomicrudite | Packstone | |

2.2. Quarry Stone Analysis

| Sample | Quarry | γ | ΔM/Mmax (%) | CI (%) | Porosity (%) | Mi (g/cm2) | CA | Ms | Crash (n. cycle) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climiti Mountains Formation | |||||||||

| Priolo stone | Mostringiano SICS | ||||||||

| P1 | 2.14 | 6.94 | 6.96 | 15 | - | - | - | - | |

| P2 | 2.06 | - | - | - | 0.85 | 0.008 | - | - | |

| P3 | 2.06 | - | - | - | - | - | 8.72 | NO | |

| P4 | 2.22 | 4.92 | 4.94 | 11 | - | - | - | - | |

| P5 | 2.24 | - | - | - | 0.54 | 0.005 | - | - | |

| P6 | 2.25 | - | - | - | - | - | 5.10 | NO | |

| Palazzolo Formation | |||||||||

| Noto stone | Porcari Tolentino | ||||||||

| N1 | 1.61 | 17.03 | 17.10 | 27 | - | - | - | - | |

| N2 | 1.63 | - | - | - | 1.39 | 0.013 | - | - | |

| N3 | 1.72 | - | - | - | - | - | 8.61 | 7 | |

| Palazzolo stone | Camelio Bagnato | ||||||||

| PL1 | 1.80 | 12.48 | 12.59 | 22 | - | - | - | - | |

| PL2 | 1.79 | - | - | - | 1.20 | 0.011 | - | - | |

| PL3 | 1.81 | - | - | - | - | - | 8.04 | 9 | |

4. Conclusions

- It is a natural material used for centuries in this context, which gives the opportunity to recover and to hand down the local construction traditions and furthermore ensures the possibility to try new ones;

- Compared to other building materials, such as concrete or ceramic bricks, the productive process has a low environmental impact, it is not harmful and it involves a low consumption of energetic resources;

- Now it is a material available in abundance, that produces smaller quantities of gray energy [23] in comparison to other materials as concrete or bricks, used more frequently;

- It guarantees less transportation costs as it is a local material;

- It is a material that lasts for a long time;

- Maintenance, substitution and selective demolition are possible according to the construction technique used and, besides, it is possible to recycle part of the material for grinding and the consequent production of inerts and sand.

References and Notes

- Pavan, V. Dove va a Finire L’architettura di Pietra. [in Italian]. Available online: http://www.architetturadipietra.it/wp/?p=1312 (accessed on 19 June 2009).

- Sariisik, A.; Sariisik, G.; Senturk, A. Characterization of physical and mechanical properties of natural stones affected by ground water under different ambient conditions. Ekoloji 2010, 19, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Marzal, R.M.; Scherer, G.W. Mechanisms of damage by salt. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 2010, 331, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Il Centro Storico di Ortygia, [in Italian]; [CD-ROM]; Comune di Siracusa: Siracusa, Italy, 2000.

- Altavilla, C.; Ciliberto, E. Cultural Heritage Materials: An XPS Approach; Nova Science: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UNI-EN, Beni Culturali—Materiali Lapidei Naturali ed Artificiali. Determinazione del Contenuto di Sali Solubili; [in Italian]; CNR-ICR: Roma, Italy, 2003; EN-11087.

- Assorbimento D’acqua per Immersione Totale. Capacità di Imbibizione; [in Italian]; CNR-ICR: Roma, Italy, 1981; NORMAL 7/81.

- Misura Dell’indice di Asciugamento (Drying Index); [in Italian]; CNR-ICR: Roma, Italy, 1988; NORMAL 29/88.

- UNI-EN, Metodi di Prova per Pietre Naturali. Determinazione del Coefficiente di Assorbimento D’acqua per Capillarità; [in Italian]; EN-1925; CNR-ICR: Roma, Italy, 2000.

- UNI-EN, Metodi di Prova per Pietre Naturali. Determinazione Della Resistenza Alla Cristallizzazione dei Sali; [in Italian]; CNR-ICR: Roma, Italy, 2001; EN-12370.

- UNI-EN, Determinazione Della Resistenza a Compressione; [in Italian]; CNR-ICR: Roma, Italy, 2000; EN-1926.

- Lo Giudice, A.; Mazzoleni, P.; Pezzino, A; Punturo, R.; Russo, L.G. Building stone employed in the historical monuments of Eastern Sicily (Italy). An example: The ancient city centre of Catania. Environ. Geol. 2006, 50, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montana, G.; Oddo, I.A.; Randazzo, L.; Valenza, M. The growth of “black crusts” on calcareous building stones in Palermo (Sicily): A first appraisal of anthropogenic and natural sulphur sources. Environ. Geol. 2008, 56, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havelcova, M.; Sykorova, I.; Trejtnarova, H.; Zeman, A. Carbon air pollution reflected in deposits on chosen building materials of Prague Castle. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 4606–4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciliberto, E.; La Delfa, S.; Panarello, S. Characterization of black scabs and role of atmospheric pollutants on their formation. In Tecniche di Analisi di Materiali nei Beni Culturali; Brai, M., Casaletto, M.P., Maccotta, A., Schillaci, S., Eds.; Carbone: Palermo, Italy, 2007; pp. 131–136. [Google Scholar]

- Torok, A. Black crusts on travertine: Factors controlling development and stability. Environ. Geol. 2008, 56, 583–594. [Google Scholar]

- Moropoulou, A.; Bisbikou, K.; Torfs, K.; van Grieken, R.; Zezza, F.; Macri, F. Origin and growth of weathering crusts on ancient marbles in industrial atmosphere. Atmos. Environ. 1998, 32, 967–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciliberto, E.; Fragalà, I.; Spoto, G. Analizing a Sicilian Renaissance Portal. Anal. Chem. 1995, 67, 249A–253A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciliberto, E.; Spoto, G. X ray photoelectron spectroscopy and auger electron spectroscopy. In Modern Analytical Methods in Art and Archaeology; Ciliberto, E., Spoto, G., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Volume 155, pp. 363–404. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, B.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X. Interaction of calcium and phosphate in apatite coating on titanium with serum albumin. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 2499–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squarcialupi, M.C.; Bernardini, G.P.; Faso, V.; Atrei, A.; Rovida, G. Characterisation by XPS of the corrosion patina formed on bronze surfaces. J. Cult. Herit. 2002, 3, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, C.; Cultrone, G.; Pezzino, A.; Russo, L.G.; Uroševič, M. Influence of pore system characteristics on limestone vulnerability: A laboratory study. Environ. Geol. 2008, 54, 1271–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In this case, grey energy is the sum of all energy required to produce goods, like material extraction, transport, manufacture, assembly, installation, dis-assembly, deconstruction and/or decomposition as well as human and secondary resources.

- Senosiain, J. Bio-Architecture; Elsevier Architectural Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, F.L. The Natural House; Bramhall House: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Buono, V. Pietre Agglomerate tra Natura e Artificio [in Italian]; Blog Architettura di pietra. Available online: http://www.architetturadipietra.it/wp/?p=1212 (accessed on 19 June 2009).

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Giuffrida, A.; Ciliberto, E. Syracuse Limestone: From the Past a Prospect for Contemporary Buildings. Geosciences 2013, 3, 159-175. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences3020159

Giuffrida A, Ciliberto E. Syracuse Limestone: From the Past a Prospect for Contemporary Buildings. Geosciences. 2013; 3(2):159-175. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences3020159

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiuffrida, Alessia, and Enrico Ciliberto. 2013. "Syracuse Limestone: From the Past a Prospect for Contemporary Buildings" Geosciences 3, no. 2: 159-175. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences3020159

APA StyleGiuffrida, A., & Ciliberto, E. (2013). Syracuse Limestone: From the Past a Prospect for Contemporary Buildings. Geosciences, 3(2), 159-175. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences3020159