1. Introduction

Geology as a scientific discipline is a relatively young science although it does have a strong historical component [

1] according to numerous treatises published in the mid-1950s [

2] in which its character as a Historic Science is emphasized [

3,

4]. However, it also reflects a clearly economic outlook with a long tradition in the literature given its evident implications in the powerful oil industry [

5] and the industry of ornamental rocks and precious stones, which have more recently been joined by the tourism industry. The latter exploits the interest aroused by geological and geomorphologic heritage as a tourist attraction [

6] to promote a new tourist category, i.e., geotourism [

7,

8,

9]. This category focuses in particular on rural tourism, which includes an ever-wider range of possibilities.

Studies on geological heritage and geodiversity as a result of a new way of understanding the role of man in his relationship with the Earth, and how both elements can be exploited to be transformed into a tourist resource, are relatively recent. This facilitates their economic exploitation and consequently their sustainable development.

The term “geodiversity” was first used in a Spanish context at the IV National Meeting of the Geological Heritage Commission of the Spanish Geological Society when some authors made the first conjectures on this concept and also put forward other new ones such as “geoconservation”. At this meeting Durán et al. (1998) [

10] expounded a series of reflections on this term and others related to it, such as those of ecological geology and geoconservation. With the intention of establishing a unified definition to serve as a reference, some authors carried out a revision of the most frequently used definitions of geodiversity. Among these we can highlight that of Nieto (2001) which defines geodiversity as the number and variety of sedimentary and tectonic structures, geological material, minerals, rocks, fossils, and soils which constitute the substratum of a region, on which organic activity, including anthropic activity, is established [

11]. For his part, Gray (2004) [

12] considers it to be the natural range of diversity of geological traits (rocks, minerals, and fossils), geomorphologic traits (landforms and processes) and soils, including their relationships, properties, interpretations, and systems. More recently and in the Spanish context, geodiversity has been defined from a legislative point of view as the entire variability of live organisms from any source, including among others land and marine ecosystems and other aquatic ecosystems of which they form part; it includes diversity within each species, between species, and of ecosystems [

13]. In contrast, geological heritage is separate from geodiversity, although they are closely related terms especially in the variety and number of places of geological interest but not in their value [

14].

The literature reveals a certain contrast between both concepts, in such a way that some authors attempt to clarify that “geodiversity aims to analyze the variability and the number of geological elements in a region regardless of their value. In other words, it is not necessary for them to be outstanding in this sense but simply for them to be present and to constitute a class sufficiently different from others to be considered a different case. While therefore in the analysis of geological heritage an essential factor is the establishing of the parameters for measuring the value of the elements allowing the comparison of cases and studies, in geodiversity it is convenient to establish classes which allow us to distinguish when an element is different from others in order to subsequently analyze its variety, frequency, and distribution” ([

14], p. 1303).

Geological heritage is an essential resource for geosciences, geoeducation [

15,

16], and naturally for geotourism [

17]. This heritage stands out because geotourist attractions as a whole differ in their physical visibility, their interpretation, and their aesthetic attraction, which are parameters determining the perception of visitors and therefore their importance as a tourist resource [

18].

Noteworthy are different studies that highlight the significance of the geosites towards developing geotourism as an activity aimed at those who desire to widen their geological knowledge. Furthermore, one could outline its application for geo-specialists and geo-experts aimed at professional training, linked to the oil industry [

19]. However, the notion of geosites as appropriate resources for the development of the tourism industry [

20] from a comprehensive viewpoint [

21,

22]. This studies cover a wide range of fields, ranging from a geographic standpoint to both geological and geomorphological ones [

23,

24], although they share a common goal, the search for rural development [

25], sustainability [

26] and, naturally, geoconservation [

27].

For the purposes of this research which concentrates on geotourism, it is considered appropriate to take as a valid reference that referring to geological heritage. Owing to this it is vital to understand two concepts which closely depend on the same, i.e., the geopark and the geosite.

The philosophy which is generated by the concept of the geopark arose for the first time during the I International Symposium on the Protection of the Geological Heritage held in Digne in France in 1991. This event saw the International Declaration of the rights of the Memory of the Earth in which the importance of geological heritage was stressed as a means of promoting sustainable local development by means of a global network of territories with geology of exceptional value. As early as 1997 the Earth Science Division of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) presented a specific program on geoparks [

28]. This type of territories was subsequently defined as “unified geographical areas where sites and landscapes of international geological significance are managed with a holistic concept of protection, education and sustainable development” ([

29], p. 3).

Geosites are of scientific interest as a result of their geology or geomorphology which may serve multiple purposes. These include research, conservation, education, and naturally sustainable development as a consequence of tourism development [

30,

31,

32]. Indeed, geoparks are beginning to be recognized as tourist destinations at which multiple synergies are exploited and which attract very varied tourist types [

33,

34]. Along these lines, some authors stress the presence of two types of geotourists, latent ones who seek novel tourist experiences, and archetypical ones who seek opportunities to develop knowledge [

35]. This geotourism is therefore a lesser known form of rural tourism which is based on traveling to and enjoying places with a unique geological character. It thus contributes towards the local development of places where this form of tourism is put into practice [

36].

Even though there is no single definition of geotourism, there is some agreement in the literature when the predominance of two clearly differentiated approaches is mentioned. On the one hand we have the geographical approach which is more generic and on the other hand the geological or geomorphologic approach, which is much more specific. Nevertheless, the latter conceptualization includes learning and geoconservation as essential principles ([

37], p. 11).

Geotourism is one of the most novel concepts in the discipline of tourism and is based on the conservation of geological heritage and geodiversity when these are managed in a sustainable manner. Nevertheless, geotourism includes many other aspects such as transport, accommodation, services at the destination, and recreation in addition to planning and management [

38].

Despite the importance of the role of geoparks and consequently of geosites as pillars which can support endogenous tourism development as reflected in numerous publications, very few references analyze the demand of these areas. There is therefore a certain lack of information, in particular if the great variety of both geoparks and locations is taken into account.

Given the scarcity of studies characterizing the tourist demand of these spaces, this study proposes a specific analysis taking as an example the Villuercas–Ibores–Jara geopark in Spain and based on a study of the demand which aims to find out the attraction capacity of this geopark for tourists or for visitors.

The initial hypothesis of the study takes as a starting point the affirmation that geotourism in the territory of the Villuercas–Ibores–Jara geopark in Spain is in an embryonic stage after over 8 years since its declaration and the investment made in promoting it. Nevertheless, we consider that its resources can directly benefit from the synergies emanating from other forms of tourism which this territory receives, which is essentially due to the fact that a plural and complementary demand exists. To confirm this hypothesis, the following objectives are established: becoming familiar with the motivations for the demand which brings visitors to the area, analyzing their mobility, and finally finding out whether there are marked differences between the behavior of tourists and visitors.

The novelty of the study lies in the differentiation between tourists and visitors who are attracted by this area and the determination of their overnight stay areas. This would obtain the internal attraction capacity generated by the geopark, which has been calculated by an analysis of networks.

3. Results

The analysis carried out based on the surveys reflects 3 different results according to whether we are concerned with visitors to the geopark as a whole or when only tourists or only visitors are taken into account (

Figure 3). A distinction is therefore made between those who spend the night in the settlements located in the same and those who spend at least one night in other places of Extremadura or not even that. The number of visitors as a whole is also analyzed to as to have a reasonable idea of the differences between various types of tourist demand.

The number of visitors as a whole is used to determine the attraction capacity of the area analyzed for those who take advantage of their stay in or their passage through Extremadura to get to know it. In addition, we analyze the demand from those with a profile clearly linked to geotourism. These are people for whom geotourism is one of the motivations for traveling to the area, although it is rarely the only one.

3.1. Visitors to the Geopark. Tourists vs Visitors

The surveys carried out at the network of tourist offices of Extremadura show that the visitors to the geopark have a profile in which visitors (69.73%) are more numerous than tourists (30.27%). It can be inferred from this that it is a very attractive destination for those staying in other places in the region. This shows the need for understanding the area’s capacity for attracting visitors. This shows the need to understand the capacity of the area to attract visitors, since it enables action in two distinct directions. On the one hand, it is required to focus on the need to attract tourists who stay overnight on the tourist accommodations located on the geopark to increase its profitability. On the other hand, there is a need to conduct a specific research regarding the place of provenance of those tourists who do not lodge at a geopark tourist accommodation, inasmuch as it would ease the process of generating specific products for their stay facilities with the aim of promoting organized trips, with specialized guides or rangers to take them around the main attraction points of the geopark. Furthermore, this has the potential to gain more control over the visits taking place in this area, with the intention of encouraging sustainable practices, given that the abovementioned venues combine geology and geomorphology with an indigenous flora and fauna, which have to be protected from the uncontrolled visits that occasionally take place.

In general, the analysis of the visitors reflects similar characteristics (

Table 4) despite the differentiation between tourists and visitors according to whether they stay at any of the 19 settlements of the geopark or not. Nevertheless, very specific differences can also be observed. It can be seen that there is a marked parity between men and women in the case of visitors, while there is a significant difference among those who spend the night in the geopark. In this latter case women account for 57.9%, while men are limited to 40.7%.

Likewise, it is well-known that tourists are older than visitors, which is confirmed because when the age of the cohorts increases the percentages are higher. Indeed, those older than 56 represent 30.5% of visitors compared with 45.1% of tourists, with the reverse being true in the case of those aged under 46. Apart from this, tourists tend to travel more as a couple (54.6% compared with 46.2%), while visitors traveling alone are more numerous than tourists (7.1%, compared with 1.9%).

When the main motivations for the demand for traveling to the geopark are analyzed there are coincidences between tourists and visitors, especially among those which are less representative (

Table 5). However, the differences are greater in some cases such as that of rural tourism, which is a motivation mentioned by 59.0% of visitors compared with 67.1% of tourists. Similar differences can be observed regarding cultural visits, which are mentioned by 79.4% of visitors and 85.0% of tourists. Nevertheless, the greatest contrast is detected when a motivation with a strong link to the geopark is analyzed, i.e., visiting mines, caves, or geological formations. In this case, the visitors who choose this option are limited to 23.6% while tourists increase to 37.9%.

The places chosen by visitors to the geopark to spend the night logically show differences between visitors and tourists (

Table 5). Among the former it can be seen that the main tourist towns of Extremadura are those from which most travelers reach this destination, especially if they are distant. In this sense it is noteworthy that 13.5% have stayed in Caceres, 10.0% in Plasencia, 8.0% in Mérida, and 7.6% in Trujillo. In other words, 43.1% of the visitors traveling to this area have stayed at the 4 major tourist destinations of Extremadura. However, the tourists who spend the night in the geopark tend to stay at Guadalupe (78.0%) or Cañamero (22.6%) or in both places. Some have even also spent the night at one of the towns with the most tourism development such as those mentioned above during their stay in Extremadura, which gives a profile of a circuit tourist who takes advantage of his stay to get to know various destinations and stay in them. This shows us once more that the geopark is attractive to tourists and to visitors who spend the night in places outside the area analyzed.

This brief analysis of the tourism demand reflected by those visiting the geopark gives us a rough idea of the profile of the traveler who comes to this area, in which the most striking aspect is the difference between tourists and visitors according to whether they spend the night at any of the establishments in the area analyzed or not. In the same way it is made clear that visitors, whether tourists or visitors, have multiple reasons for traveling, owing to which in most cases we are concerned with tourists who enjoy cultural visits, especially to Guadalupe, and at the same time practice rural tourism and complement it with gastronomy. Moreover, in the cases of both tourists and visitors a certain interest in enjoying rivers and reservoirs, sites of geological interest, and even birdwatching is detected.

If we resort to drawing up a linear correlation array which compares the replies reflected by the demand from visitors, it is evident that we can speak of common characteristics which serve to clearly differentiate tourists (

Table 6). On the other hand, we have those which have a clear link with nature tourism as there are significant correlations when we compare motivations for tourism in rivers, gorges, or reservoirs with birdwatching or observing the sky and in part with practicing rural tourism. On the other hand, a well-defined group appears which only shows interest in cultural tourism, which is closely related to gastronomy and oenology. Moreover, there is also a very peculiar group, geotourists, the essential motivation of which is visiting mines, caves, and geological formations but which at the same time takes advantage of the stay to enjoy highly active tourism, watching birds or observing the sky or carrying out aquatic activities given the presence of rivers, gorges, and reservoirs, and at the same time enjoying gastronomy or oenology, although they do not tend to make cultural visits.

From all this it can be inferred that visitors to this area have a dual profile, on the one hand practicing typically cultural tourism and on the other active tourism linked to nature with a clear preference for geotourism.

3.2. Geotourists vs the Remainder of Visitors

A comparative analysis of those who affirm that they practice geotourism and the remainder of the visitors to the geopark reflects significant similarities to that existing between tourists and visitors (

Table 7). It is not for nothing that most tourists in this sector declare that they visit caves, mines, and geological formations. This is therefore a type of generic demand from tourists existing in the area analyzed and a significant difference cannot be established between both types of visitors.

The analysis of the motivations and the overnight stay locations reveals significant differences between geotourists and other visitors (

Table 7). In this sense visiting mines, caves, and geological formations stands out as an essential reason for traveling to the geopark, which is obvious as it is the only area in Extremadura where Appalachian relief can be contemplated, apart from its recognition as a world geopark by the UNESCO. It is clear that geotourists seek the enjoyment of this type of spaces and take advantage of their stay in Extremadura to carry out other activities like any other kind of traveler; there is also a certain coincidence between them. During their stay in Extremadura they therefore visit places with a recognized cultural heritage; it should not be forgotten that the Real Monasterio de Guadalupe, which is a world heritage site, is located within the geopark, in addition to other tangible or intangible cultural resources. They also tend to practice rural tourism and tourism related to water in rivers or gorges and reservoirs and naturally to enjoy the rich and varied gastronomy. It can also be seen that birdwatching and observing the sky are activities which attract numerous visitors.

It is, therefore, clear that geotourists differ from the remainder of visitors to the geopark only in certain aspects, which are not socioeconomic but rather regarding behavior, habits, and preferences (

Table 8). This fact reveals that those who visit this area do so for very varied reasons, from which it can be understood that they have a mixed vocation in which the desire to visit geosites naturally stands out. They do not however miss the chance of enjoying the cultural heritage and the gastronomy. Moreover, natural landscapes attract considerable interest, not only as a result of their geological and geomorphologic peculiarities but also their rich fauna and flora.

All this constitutes irrefutable proof of the fact that the area analyzed has more than enough characteristics to attract visitors, not only those who intend to spend the night at any of its 19 towns and villages; they also captivate tourists who are staying in more distant places. According to the survey, 41.4% of the geotourists polled spend the night in the area at the two emblematic settlements within the geopark. To be precise, 30.5% do so in Guadalupe and 10.9% in Cañamero, although the main tourist destinations of Extremadura also stand out as overnight centers, including Caceres (9.1%), Plasencia (7.6%), and Mérida (6.9%).

The remainder of visitors, i.e., those other than geotourists, are governed by the same rules when choosing where to spend the night. In this case, 20.9% spend at least one night in Guadalupe and 5.3% do so in Cañamero, which makes clear the great difference between both types of demand. Likewise, the volume of tourists who have stayed in other places in Extremadura reveals some significant differences which affect the main tourist destinations of the autonomous region. These discrepancies can be observed in those who spend the night in Caceres, the figure for which rises to 12.9% (+3.8%), or Trujillo which attains 7.5% (+3%). The obvious reason is that the destination of the latter variety of tourists is the settlement of Guadalupe and more precisely its emblematic monument, the Real Monasterio de Santa María of Guadalupe.

3.3. Attraction Capacity of the Geopark for Visitors

If we consider the volume of visitors traveling in the geopark or spending the night there, it is significant that most of the travelers polled have not spent the night in the area. Indeed, 87.1% of the latter come from the 40 main destinations of Extremadura. In their turn, 30.4% of them have spent at least one night in Guadalupe or Cañamero, the two settlements which account for a large part of the accommodation available. In contrast, 56.7% have stayed outside the geopark. The remainder of the towns of the region which provide visitors to the area under study represent 12.9% of the demand and their effect is low. For this reason, the analysis of mobility has only included the towns which contribute 0.1% to the tourism system of this area.

As can be observed in the analysis of the flow of visitors (

Table 9), Guadalupe appears as the settlement where more overnight stays are recorded as 23.6% of those visiting the geopark pass at least one night there. The important role played by this town is due to its large number of beds and its tradition as a center for pilgrims [

24] in combination with its important cultural heritage. It is also significant that 6.8% of the visitors stay in Cañamero within the geopark, although this town cannot compete with the rich tourism potential of Guadalupe.

Outside the territory of the geopark it can be observed that an important number of visitors stay at the main tourist towns of Extremadura, owing to which they usually make use of a day or travel to and from their habitual places of residence in order to pass through the study area. These population centers include in particular Caceres, Plasencia, Mérida, and Trujillo, despite the distance between them and the main reception center, Guadalupe. It should be stressed that between 11.8% of the tourists of Caceres and 6.7% of those lodging in Trujillo decide to travel to this area for varied reasons, albeit always related to nature, cultural heritage, and naturally the local gastronomy.

As the number of tourists of any of the towns of Extremadura decreases, their capacity to divert tourists to the geopark evidently falls sharply. Indeed only 14 towns of Extremadura provide over 1% of visitors to this space, which if we omit the 2 settlements located in the area under study accounts for 48.7% of the total number of travelers. This confirms a major concentration in the origin of the travelers.

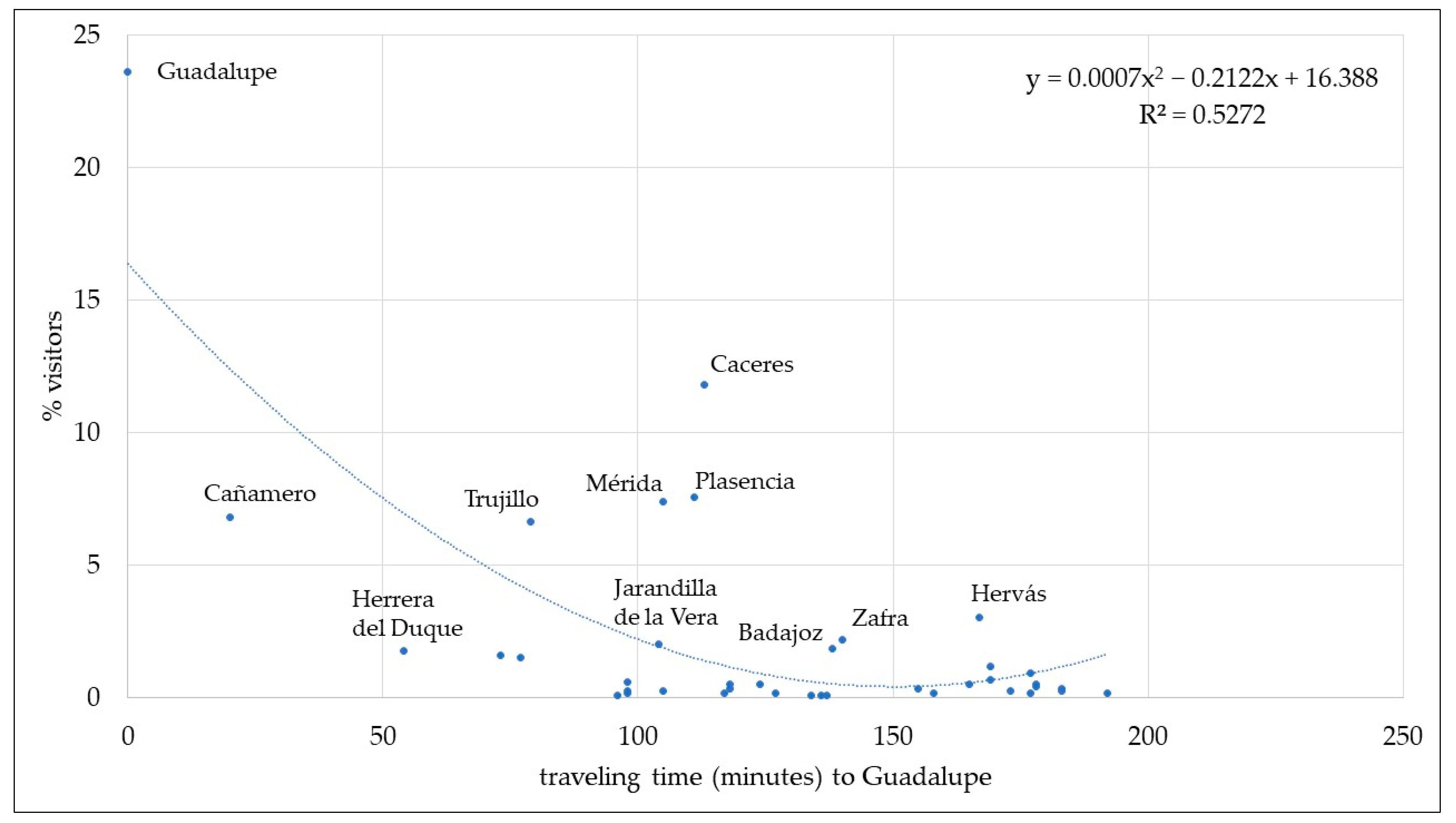

When the overnight stay locations of the visitors are compared with travel times to Guadalupe, in the Villuercas–Ibores–Jara geopark (

Figure 4) it is clear that interest in their visit falls significantly. This sharp drop is related to two aspects—distance and the number of tourists staying in areas sending visitors. Indeed, it is clear that the most tourist-orientated towns of Extremadura, such as Caceres which in 2017 received a total of 312,930 tourists; Mérida which received 260,153; Plasencia with 102,908 and Trujillo with 96,522 [

56] are those diverting the largest number of visitors to the geopark. However, the travel time from the overnight stay locations to the geopark also plays an important role. Indeed, without considering who stay in the area under study, it is observed that there is a sharp drop as travel time increases, a circumstance contrasted at other destinations [

59].

The fastest routes connecting the overnight stay area with Guadalupe reveal a situation very similar to that previously described, in which it is noteworthy that the most significant percentages of origin start from the main tourist destinations. Likewise, it is clear that an increase in travel time is an important factor to dissuade visitors from traveling to the geopark (

Figure 5).

The specific analysis of the various motivations for traveling shows once again that the capacity for attracting visitors is very varied and depends to a large extent on aspects such as the volume of tourists captured by the overnight stay locations and by proximity. In contrast, as can be observed the differences are not great in the case of the various reasons for making the visit. This is clearly noticeable in the case of visits to caves, mines, or geological formations (

Figure 6a), a priori the strong point of the geopark, although as has been mentioned it also holds a noteworthy cultural (

Figure 6b) and natural heritage (

Figure 6c). Despite this circumstance, it can be observed that the capacity for attracting geotourists is stronger but is not so wide-ranging, although in the case of generic rural and cultural tourism the opposite is true; it is less intense but attracts visitors who are staying in more distant places.

4. Discussion

The results obtained allow the confirming of the initial hypothesis proposed at the start of the study, in which it was assumed that geotourism was incipient in the area analyzed. It is not for nothing that the geopark itself was recognized as such in 2011 although it did not acquire the status of a UNESCO world geopark until 2015. Despite the repeated attempts of various public administrations, this theme has not a widespread effect on the tourism demand as is reflected by two undisputable facts. The first is that in 2017 the geopark received only 34,891 travelers who gave rise to 56,744 overnight stays [

56], and the second is that although it captures a large number of visitors, they pay more attention to cultural tourism than to geotourism. This is collaborated by the fact that even among geotourists 81% stated that they made cultural visits.

The presence of a demand divided between cultural and rural tourism has been a constant both if we consider visitors and tourists or geotourists with the remainder of visitors. This may however be a real competitive advantage if it is considered that numerous tourism resources come together in this area and above all if the relationships between the reasons given by the tourist to visit the area are analyzed. In them a clear relationship can be observed between all the activities that can be linked to the rural world. Indeed, the geotourist also recognizes that he practices generic rural tourism and takes part in activities such as birdwatching or the observation of the sky, in addition to enjoying local rivers and reservoirs and those further afield. A demand of this kind may mean a major shakeup if it is capable of generating a specific tourism product which is capable of arousing greater interest in a space such as this, where one can enjoy nature in general and geology and geomorphology in addition to getting to know the huge architectural and cultural heritage which it boasts [

33].

It is curious that several companies specializing in free-time activities operate in the area, which is no doubt appreciated by the tourists who spend the night there, but there is a lack of a specific product capable of transforming visitors into tourists owing to the fact that they stay in other places where scarcely any information on the geopark can be found. This means that an excellent opportunity is being lost to promote this space to take better advantage of the accommodation infrastructure which in 2017 offered a total of 1387 beds, of which barely 13% are occupied as an annual average [

56].

These circumstances show that specific action is still needed with a view to encouraging knowledge of the geopark, starting by showing the geosites as points of specific interest and gradually generating a “geoculture” among visitors, and above all creating specific products at the main tourism points of Extremadura, which divert an important proportion of visitors towards this space.

From this derives the need to become familiar with the real attraction capacity which this area has for other visitors spending the night in various places in Extremadura, an aspect which has been neglected in the specific literature on the geopark. This mainly focuses on the geological and geomorphological aspects, although just very recently, it has started focusing on the touristic demand as well as on the characteristics and features from the visitors of this destination [

60].

Owing to this reason, the study we present here makes an important contribution as certain facts which were assumed by the experts and not been demonstrated have been corroborated. In contrast however, it has been shown that the geopark has a peculiar tourism demand which is open to the enjoyment of the resources offered by the destination, but also boasts a noteworthy capacity of attraction for travelers lodging in towns such as Caceres, Mérida, Trujillo, and Plasencia, the 4 main destinations of the region. However, specific products have not been designed in these towns, owing to which the need is emphasized for creating them and thus avoiding unorganized travel by tourists and possibly without enjoying the great richness of this space. As can be observed, it is a case of generating products which aim to achieve two objectives. On the one hand, the capturing of tourists, and on the other encouraging knowledge and enjoyment of this area, and making use of the synergies that may exist with the activity companies operating in the geopark. This would also contribute towards the rational and sustainable use of the resources, in particular when one of the main attractions of the area is that of its natural surroundings.

It is, therefore, noteworthy that the resources available are more than sufficient to attract a varied group of visitors, as is shown by the reasons for traveling to Extremadura and by extension to the geopark. However, the resources are not made use of correctly, owing to which this is one of the main circumstances which could be a follow-up to this study.

According to the results of this research, it is viable to consider that once geotourism, in different areas, and its pertinent demand are analyzed, examining the place of origin of the visitors would be recommended, since that would serve as a base for measuring the attraction capacity and, above all, to promote touristic politics aimed at the design of product orientated towards the characteristics of those visitors and to offer them in their overnight stay accommodations. By doing so, it might be possible not only to enhance the touristic experience, but also to allow for a sustainable development and endogenous to the analyzed area.

Obviously, the previously shown result focus on the analysis of a specific geopark and cannot be generically extrapolated to the rest, since the casuistry is severely different. However, there may be a chance to replicate the methodology proposed in the study to other geoparks with common characteristics: low incidence on tourism, poor geological knowledge of visitors and locals or the presence of other tourism resources. This methodology would imply a discriminatory analysis of the characteristics that define both tourists and visitors. At the same time, this differentiated analysis can be considered to be a necessary element and be addressed from the perspective of tourists’ mobility on their destinations.

5. Conclusions

The main conclusions obtained from this research concentrate on the combined analysis of the tourism demand, and more specifically on its characteristics, in addition to the capacity of the geopark for attracting visitors.

Firstly, it has been confirmed that there are only minor differences between tourists and visitors in the area under study, basically those of certain age groups, gender, and origin. These differences are not sufficient to establish a clear separation unless the main reasons for the journey are analyzed. In this case, a clear division can be appreciated between typically cultural and rural tourists.

Secondly, it was found that those with a profile similar to that of the geotourist only show clear differences in their motivation for traveling, as they mention visits to caves, mines, and geological formations as a reason for traveling to the destination.

Thirdly, it has been detected that the geopark has a power of attraction for visitors spending the night in other places, i.e., the main tourist destinations of Extremadura. In other words, its attraction capacity has a direct relationship with the tourist importance of the overnight stay locations, although the duration of the journey also acts as a considerable limitation. Indeed, when travel time exceeds 2 h the percentage of visitors who have spent the night in other places of the region decreases. Moreover, there are no significant differences in the attraction capacity of this area for cultural or rural tourists, as the area studied has excellent examples of both kinds of resources.

Fourthly and finally, it is concluded that there are no tourism products to encourage traveling to this destination from the main tourism points of Extremadura, which would lead to a considerable improvement of the main parameters defining the tourism system of the geopark.