Abstract

The impact of dietary phytoestrogens on human health has been a topic of continuous debate since their discovery. Nowadays, based on their presumptive beneficial effects, the amount of phytoestrogens consumed in the daily diet has increased considerably worldwide. Thus, there is a growing need for scientific data regarding their mode of action in the human body. Recently, new insights of phytoestrogens’ bioavailability and metabolism have demonstrated an inter-and intra-population heterogeneity of final metabolites’ production. In addition, the phytoestrogens may have the ability to modulate epigenetic mechanisms that control gene expression. This review highlights the complexity and particularity of the metabolism of each class of phytoestrogens, pointing out the diversity of their bioactive gut metabolites. Futhermore, it presents emerging scientific data which suggest that, among well-known genistein and resveratrol, other phytoestrogens and their gut metabolites can act as epigenetic modulators with a possible impact on human health. The interconnection of dietary phytoestrogens’ consumption with gut microbiota composition, epigenome and related preventive mechanisms is discussed. The current challenges and future perspectives in designing relevant research directions to explore the potential health benefits of dietary phytoestrogens are also explored.

1. Introduction

In the past decades, the research regarding the beneficial or adverse effects of phytoestrogens present in the human diet has intensified, due to their estrogenic or anti-estrogenic potential in humans and animals [1,2,3]. Phytoestrogens are found in a wide variety of foods, including soy-based products, fruits, vegetables and dairy products [4,5,6]. A huge list of health benefits, including a reduced risk of osteoporosis, hormone-dependent cancers, cardiovascular diseases and brain disorders, as well as decreased menopause symptoms, is often ascribed to phytoestrogens. However, they can act as endocrine disruptors, being able to induce adverse health effects, as well [7,8]. Based on their presumptive beneficial effects on human health, the amount of phytoestrogens consumed in the daily diet has increased considerably worldwide [9,10]. Nowadays, a plethora of dietary supplements based on phytoestrogens has overflowed the market, and their consumption has reached high levels, especially within the female population. Thus, there is a growing need for relevant scientific data regarding their impact on human health.

Indeed, new insights of phytoestrogens’ bioavailability and metabolism have been unveiled, and a more complex image of biological activities of absorbed phytoestrogens and their metabolites has emerged [11,12,13]. The phytoestrogens can be active in the human body as free molecules or as gastrointestinal tract (gut) metabolites, being able to interfere with the endogenous estrogen signaling and associated cellular processes [2].

In general, the key factors that are affecting the bioavailability of phytoestrogens are the age and gender of individuals, food matrices, dose frequency and the ADME (absorption, tissue distribution, metabolism and excretion process) properties. Each class of dietary phytoestrogens (e.g., isoflavones, coumestans, prenylflavonoids, lignans and stilbenes) has its own structural particularities, and studies regarding their bioavailability and metabolism are still far from being completed. An important inter-and intra-population heterogeneity of final metabolites production have been observed in human population [14,15]. Their metabolism is mediated both by tissue enzymes and gut microbiota, either prior to absorption or during enterohepatic circulation [16,17]. Only a small percentage (5–10%) of ingested phytoestrogens can reach the small intestine and are available for absorption into enterocytes and then enters into systematic circulation towards target tissues [18,19]. A substantial part of them undergoes extensive metabolization across the liver, small and large intestines, where they are transformed into metabolites with various chemical structures and bioactivities [12,20,21]. The beneficial effects of phytoestrogens on human health are now considered to be partially influenced by their metabolites, such as S-equol, O-demethylangolensin (O-DMA), enterolignans and stilbenes derivatives. In some cases, these metabolites have greater biological activities and sometimes have different impacts on targeted tissues than their precursors [12,21].

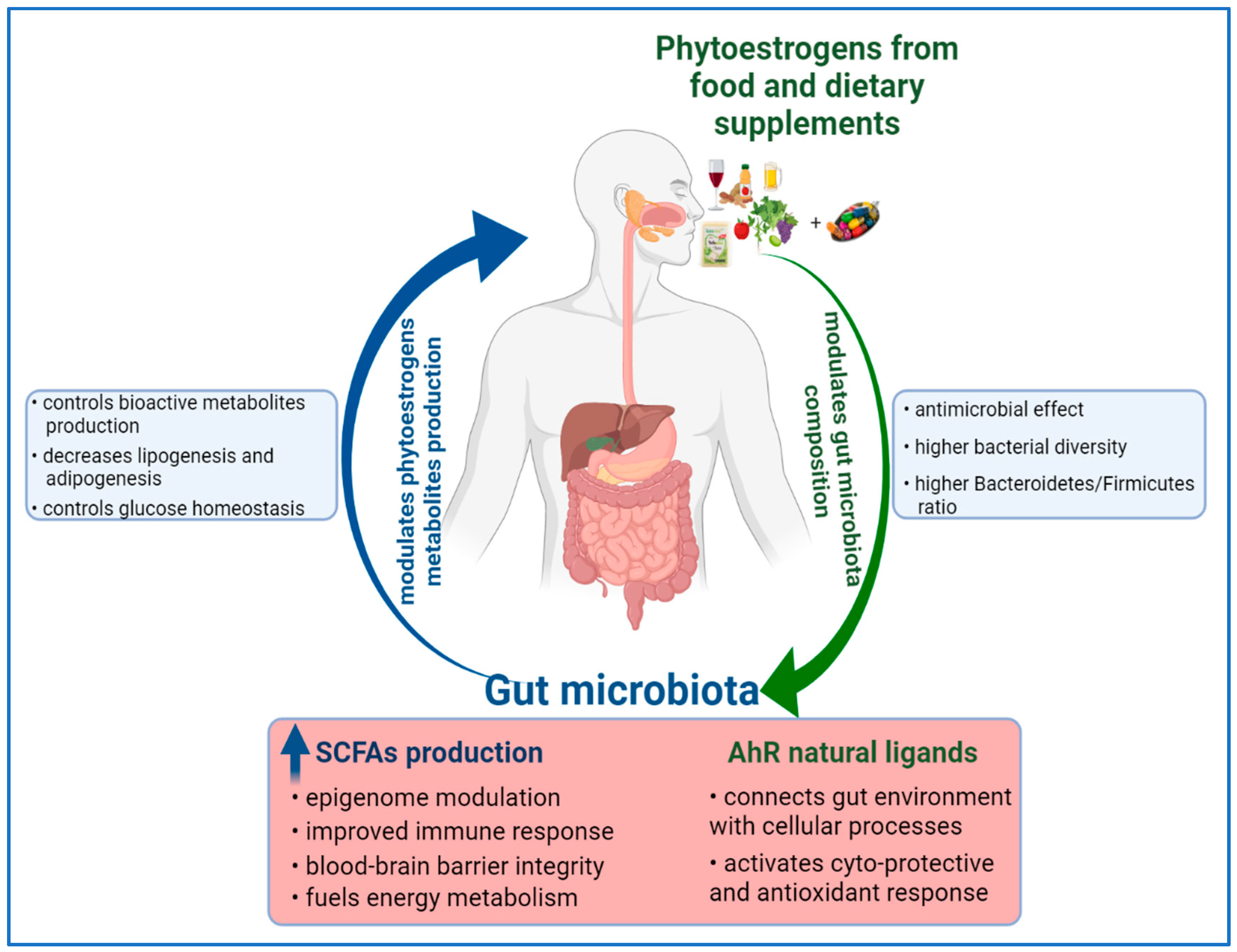

On the one hand, the composition of gut microbiota can influence the metabolism of phytoestrogens; on the other hand, phytoestrogens and their metabolites can modulate and reshape the gut microbial composition [13]. Understanding their reciprocal influence, and by deciphering the molecular basis of phytoestrogens and microbiome interaction, it can be the key to elucidate their influence on human health.

For many decades, epidemiologic studies have been trying to find associations between dietary components and disease risks. Nevertheless, multiple factors, such as variations in daily consumption patterns of individuals, results based on empirical analyses on predetermined sets of dietary components and human genetics and metabolism heterogeneity have led to inconsistent results. Despite strong preclinical evidence, the association of dietary phytoestrogens with human disease risks has not yet clearly demonstrated [1,7]. Recently, the European Food Safety Authority has indicated that isoflavones intake of 35–150 mg/day is safe and that there is no concern of possible adverse effects in peri-and post-menopausal women [22]. Moreover, new reports have concluded that consumption of phytoestrogens and its correlation with circulating metabolites is not reliable because of high inter-individual variabilities of microbiota composition and genetic polymorphism of phase-I and -II enzymes [12,23].

In recent years, emerging evidence has highlighted the role of dietary bioactive compounds in modifying the epigenome by directly or indirectly engaging in epigenetic mechanisms controling gene expression [24]. Epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation, histone post-translational modifications, chromatin remodeling and noncoding RNAs expression, represent the link between genotype and phenotype. Each epigenetic mechanism is reversible and is controlled by specific protein classes which attach, dislodge or maintain specific chemical groups that can signal the initiation or inhibition of gene transcription [25]. These proteins, along with chemical marks attached to DNA, RNA and histones, represent the epigenome, a complex regulatory network that modulates chromatin structure and genome function [26]. When this regulatory circuit is discontinued, normal physiological functions are affected, leading to carcinogenesis or occurrence of other chronic diseases [27]. The epigenome is a dynamic network that undergoes continuously modifications in space and time, stimulated by internal and external factors [26,28]. Environmental factors, including diet, can remodel the epigenome during lifespan from embryonic stage until aging in a beneficial or detrimental way. Many dietary components display several biological activities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticancer properties that might play a significant role in chronic disease prevention [24]. Importantly, strong scientific evidence implies that consumption of dietary phytochemicals can maintain the epigenome at normal parameters that support a healthy phenotype, and also it can reverse abnormal gene expression [24,29]. For example, it has been demonstrated that dietary phytochemicals can influence the DNA methylation patterns by altering the substrates and cofactors of 5-Methylcytosine (5mC) reaction, or by inhibiting the enzymes of one-carbon metabolism and by blocking the proteins involved in DNA methylation/demethylation activity [29,30].

The present review discusses the new insights regarding dietary phytoestrogens’ bioavailability and metabolism, pointing out the diversity of their gut metabolites and the complexity of metabolic pathways, followed by each class of phytoestrogens (e.g., isoflavones, coumestans, prenylflavonoids, lignans and stilbenes). In addition, it draws attention to emerging scientific data that sustain the epigenetic modulator capacity of each class of dietary phytoestrogens and their metabolites and the generated impact on several cellular and molecular processes connected with human health. The interconnection of dietary phytoestrogens with gut microbiota, epigenome and related oxidative stress events is presented. In-depth studies of dietary phytoestrogens and their metabolites mechanisms of action at the molecular level can represent an effective approach to undestand how to reverse aberrant epigenetic modifications, reshape gut microbiota and suspend abnormal cellular functions, which consequently will prevent and/or attenuate chronic diseases.

2. Phytoestrogens—General Data

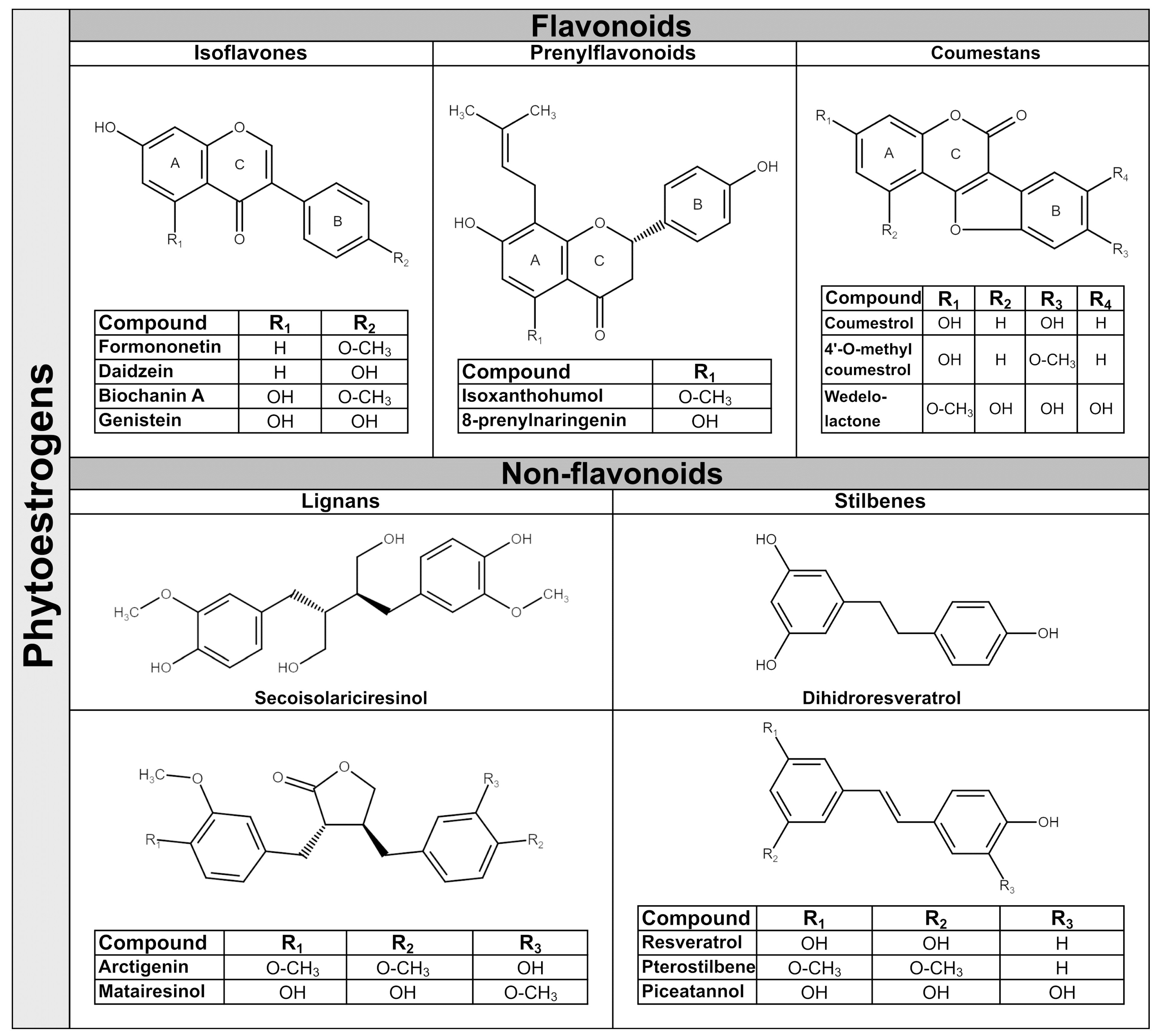

Phytoestrogens are synthesized in plants as secondary metabolites during stress-cultivation conditions and UV radiation, and as a response to pathogens attack. They have antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral and antioxidant properties in plants [31]. The amounts of phytoestrogens produced by a plant increases significantly during extreme growing conditions [32], and by growing the plant in an organic environment [33]. In general, a single plant often contains more than one class of phytoestrogens. For example, the soy bean is rich in isoflavones, whereas the soy sprout is a potent source of coumestrol, the main representative of coumestans class [34]. In terms of chemical structure, phytoestrogens are nonsteroidal polyphenols having several common characteristics with mammalian hormone, estradiol. The structural prerequisite for phytoestrogen molecule to bind the estrogen receptor is the presence of phenolic rings and a pair of hydroxyl groups separated with a similar distance, as in the case of estradiol molecule [35]. The phytoestrogens have been categorized in flavonoids and non-flavonoids. Flavonoids consist of a fifteen-carbon skeleton organized in two benzene rings (A and B) linked by a heterocyclic pyran structure (C) as C6–C3–C6, as Figure 1 shows. The basic flavonoid skeleton can have numerous substituents, including hydroxyl groups usually present at the 4′, 5′ and 7 positions. Most of plant flavonoids have sugar molecules attached to their aglycones, so they mainly exist as glycosides [36]. Further subclassification of flavonoids in isoflavones, coumestans and prenylflavonoids is based on structural differences in the connection between the B and C rings, as well as the degrees of saturation, oxidation and hydroxylation of the C ring [36]. Non-flavonoid phytoestrogen’s structure consists of phenolic acids in either C6–C1 (benzoic acid) or C6–C3 (cinnamic acid) conformations, and are represented mainly by lignans and stilbenes [36].

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of representative dietary phytoestrogens.

2.1. Isoflavones

Isoflavones are the main subgroup of plant flavonoids that is found in the Leguminosae family, including soy (Glycine max L.), red clover (Trifolium pratense L.), alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) and species of Genista [37]. They have diphenol structures and are produced in higher plant through the phenylpropanoid pathway. Two of most important isoflavones have similar structures; thus, daidzein differs from genistein by lacking a hydroxyl group at C5 position [38]. The representative dietary phytoestrogens’ chemical structures are presented in Figure 1.

Isoflavones are found often in plants as glycosides (genistin, daidzin and glycitin) and in a lower amount as aglycones (genistein, daidzein, glycitein), or as 4′ methylated derivative aglycones (biochanin A and formononetin) [36,39]. The presence of hydroxyl groups and sugars increases their solubility in water, whilst methyl groups confer to them lipophilicity [40]. In the human diet, the main source of isoflavones are soy and soy-derived products, but small quantities of isoflavones are also found in chickpeas, beans, fruits, vegetables and nuts [6,41]. In Western countries, the cow’s milk and dairy products contain significant amounts of isoflavones [5]. Due to their pleiotropic activities, isoflavones are considered as a natural alternative for the treatment of estrogen decrease-related conditions during menopause, cardiovascular diseases and other hormone disorders [42].

2.2. Prenylflavonoids

Prenylflavonoids structure contains a flavonoid skeleton that has attached at position 8 of A ring a lipophilic prenyl chain [43]. Prenyl chains appear in various forms, and the most notable are 3,3-dimethylallyl substituent, geranyl, 1,1-dimethylallyl and their moieties. The presence of hydrophobic prenyl radical increases prenylflavonoids cellular uptake and biological functions by accelerating interactions with the phospholipid layers of cellular membranes or hydrophobic target proteins. Therefore, they are considered to be more biologically active than corresponding flavonoids. Prenylflavonoids have a narrow distribution in plants in several families, including Families of Leguminosae (Glycyrrhiza glabra), Cannabaceae (Humulus lupulus L.), Berberidaceae (Epimedium brevicornum M.), Rutaceae and Moraceae [44]. The most studied prenylflavonoids are those found in hops (Humulus lupulus L.), the main raw material for beer production. The representative hop’s prenylflavonoids are xanthohumol (XN); isoxanthohumol (IX), which is produced during the brewing process from XN; 6-prenylnaringenin (6-PN); and 8-prenylnaringenin (8-PN) [43]. In particular, 8-PN can be derived from desmethylxanthohumol (DMX) in the brew kettle, yet it can be converted from IX by human microbiota and by liver enzymes [45]. Other prenylflavonoids which have aroused interest in recent years are icariin, a prenylated flavonol glycoside present in Herba epimedii that has been used in Chinese traditional medicine for centuries [46]; and glabridin, which is considered a Glycyrrhiza glabra species-specific compound. Glabridin is a prenylated isoflavan with a pyran-substitution at the A-ring and with a high content in dried roots of licorice [47]. As hops are used in beer production, so beer is representing the main source of dietary prenylflavonoids, with IX the major hop prenylflavonoid present in human diet up to 3.44 mg/L [48]. Hops extracts are used in traditional medicine as an antifungal and antibacterial remedy, also to treat insomnia or stomach pain. Recently the hop’s phytoestrogens have gained increasing interest due to their stronger biological activities compared with isoflavones [49]. The presence of prenyl chains allows the prenylflavonoid molecules to interact with the hydrophobic pocket of the estrogen receptors based on in silico modeling studies [50]. The 8-PN is a selective phytoestrogen which has a higher affinity for ERα, having only a 70-times-lower affinity compared to 17β-estradiol [48]. Similar to all other phytoestrogens, prenylflavonoids exert also antioxidant and antitumor activities with greater potential than isoflavones or their flavonoids precursors [51].

2.3. Coumestans

Coumestans are produced by oxidation of pterocarpan, a precursor of isoflavonoid phytoalexins from plants, and consist of a benzoxazole fused to a chromen-2-one structure [52]. The coumestans are found mainly in Leguminosae family, including alfalfa (Medicago sativa), red and white clover (Trifolium pratense or repens) and soybean (Glycine max) [34]. The most-documented coumestans is coumestrol, which is abundant in all species mentioned above. Coumestrol, in addition to flavonoid structure, has a furan ring in the junction between the C and B rings and hydroxyl groups at the C4 and C7 carbons, similar to the structure of estradiol [53]. Interestingly, the coumestrol can be produced in plants from daidzein under stresses conditions such as germination, fungal infection, or chemical elicitors [54]. Other coumestans present in food or medicinal plants are 4′-methoxycoumestrol, repensol, wedelolactone and their derivates [52]. Wedelolactone, the active ingredient of herbal medicine derived from Asteraceae family, has been extensively used in South American native medicine as snake antivenom [55]. In traditional Chinese medicine, coumestans are used to treat septic shock and in Indian Ayurvedic medicine as a treatment for liver diseases, skin disorders and viral infections [56]. Coumestrol is considered the most potent phytoestrogen with an affinity for mammalian estrogen receptors only 10–20 times lower than 17β-estradiol [53]. In addition, its antioxidant activity is considerably higher than genistein and daidzein [57]. Coumestans are less common in human diet than isoflavones, but they are present in food plants, including split peas, pinto and lima beans, spinach, broccoli, brussels and soybean sprouts with amounts between 0.025 and 281 mg/kg fw [4].

2.4. Lignans

Lignans have a wide distribution in plants, being present in more than 55 plant families, including Lauraceae family, especially genera of Machilus, Ocotea and Nectandra; and others such as Annonaceae, Orchidaceae, Berberidaceae and Schisandraceae [58]. They are found throughout the plant tissue, namely in roots, rhizomes, fruit, stems, leaves and seeds, with the highest concentrations found in flaxseed [58]. Their biosynthesis originates from the metabolism of phenylalanine with the production of monolignol, the lignan and lignin precursor. Even though lignans are not considered to be dietary fiber, by sharing the same precursor with lignin, an insoluble fiber present in all plant cell walls, can influence lignans’ metabolization [59]. Structurally, lignans are stereospecific dimers of monolignol interconnected between the C8 and C8′ positions, and further linked to either, lactone or carbon bonds. They possess a large structural diversity and are present in plants as aglycones, glycosides with one or more sugar groups, esterified glycosides or as bio-oligomers [60]. Pinoresinol (PINO) is the precursor of the most abundant plant lignans secoisolariciresinol (SECO) and of matairesinol (MAT), which is a dibenzylbutyrolactone. SECO has a dibenzylbutane structure and its diglucoside form, Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) accounts for over 95% of the total lignans found in flax [61]. Several other lignans characterize plant foods, including lariciresinol (LARI), medioresinol (in sesame seeds, rye and lemons), syringaresinol (in grains), sesamin and sesamolin (in sesame seeds) [4]. Other lignans, such as arctigenin, have a dibenzylbutyrolactone structure, which is the main component of Arctium lappa, being used in Japanese Kampo medicine for its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antiviral activity [62]. Plant lignans are known to display a wide range of biological functions, including weak estrogenic and cardioprotective activities, as well as anti-estrogenic and anticarcinogenic properties [17]. In general, plant lignans are considered to be precursors of more bioactive molecules, known as mammalian lignans, enterolactone (ENL) and enterodiol (END), which are produced by colonic microbiota. Plant lignans are the principal source of dietary phytoestrogens of Western diet [63].

2.5. Stilbenes

Stilbenes are non-flavonoids containing two phenyl moieties connected by an ethylene bridge that generates two isomers (cis and trans), with trans-isomer as the most stable and biologically active [64]. They are synthetized through the phenylpropanoid-acetate pathway in response of plant’s defense system, as in the case of flavonoids. More than 400 stilbene compounds have been identified in plants, with various structures from monomers to octamers with different substituents, such as glycosyl, hydroxyl, methyl or isopropyl radicals. A high content of stilbenes has been found in species such as Gnetaceae, Pinaceae, Cyperaceae, Fabaceae, Moraceae and Vitaceae [64]. The most studied stilbenes are the monomeric ones, including resveratrol, pterostilbene and piceatannol. They are naturally occurring in fruits, mostly in grapes, berries and peanuts [65]. In general, the occurrence of stilbenes in human diet is limited, but represents an important part of phytoestrogens intake by people consuming a Mediterranean diet or who regularly are drinking wines. Resveratrol is a trans 3,5,4′-trihydroxystilbene and exists mostly as piceid, its glycosidic form, in red and white grape juice [66]. The red-grape juices contain high amounts of trans-piceid, followed by cis-piceid and trans-resveratrol [66]. Piceatannol as a trans 3,4,3′,5′-tetrahydroxystilben that is naturally present in both red and white grapes, berries, passion-fruit seeds and white tea [67]. During the wine fermentation process through hydroxylation, the resveratrol is converted to piceatannol [68]. Pterostilbene is the 3,5-dimethoxy analogue of resveratrol which is found in Dalbergia and Vaccinium species. The presence of the two methoxy groups makes pterostilbene molecule more liposoluble, increasing its bioavailability as compared to resveratrol [69]. The stilbenes are known for their antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cardiovascular and neuroprotection properties [70].

3. Bioavailability and Metabolism of Dietary Phytoestrogens

The absorption rate of dietary phytoestrogens is determined primarily by their chemical structure and by factors such as molecular size and solubility, extent of glycosylation, hydroxylation, acylation and degree of polymerization [71]. In general, their absorption rate is low, signaling intense metabolism with the formation of metabolites by gut microbiota or by enzymes from liver. Most of ingested phytoestrogens are in glycosidic forms (e.g., isoflavones, lignans and stilbenes), and the first step of their metabolism is their conversion into corresponding aglycones. Metabolism of dietary phytoestrogens in humans follows the detoxification steps of drugs through two phases. Phase I consists of mainly oxidation and hydroxylation reactions catalyzed by enzymes such as cytochrome P450s and flavin-containing monooxygenases [72]. Phase II consists of conjugation reactions, resulting in metabolites with small polar molecules attached that facilitate their excretion in urine or bile [73]. Most of the phase-II metabolites are usually less active or completely inactive than phase I metabolites. Further, the free aglycones and part of gut metabolites can be re-conjugated subsequently by phase-I and -II enzymes within enterocytes and hepatocytes to increase their solubility in body’s fluids [74]. From this reason, there is a high percentage of conjugated metabolites in human plasma. In the case of isoflavones, almost 75% of them are glucuronide conjugates, approximatively 24% are sulfated and only 1% are free aglycones [15]. Once in the bloodstream, phytoestrogens and their metabolites can reach target tissues and, later on, are excreted in urine or bile. Moreover, the metabolites can be de-conjugated by microbiota to release the free aglycones, which are absorbed by the intestine via enterohepatic re-circulation or finally are excreted in feces [20,72]. Bacterial strains from gut are able to catalyze an array of reactions that play key roles in the metabolism of phytoestrogens, including hydrolysis of esterified and conjugated bonds, deglycosylation (removal of sugar moieties), demethylation (substitution of a methyl by a hydroxyl group), dehydroxylation (reduction of hydroxyl groups), dehydrogenation and reduction. In the following subsections, the metabolism of each class of dietary phytoestrogens is presented, pointing out the relevant scientific data gained in the past years.

3.1. Isoflavones

Generally, the isoflavones are present in food as glycosides and, to a less extent, as deglycosylated molecules. However, the fermentation process used to obtain specific soy products can increase the concentration of aglycones in processed soy. Once ingested, the glycosidic isoflavones can be hydrolyzed along whole gut by either brush-border enzyme of gut mucosa [75] or by β-glucosidases of different bacterial species, such as Bifidobacteria, Escherichia coli and Lactobacillus. As studies with human subjects have revealed, aglycones are more likely to be absorbed in the small and large intestines, due to their higher lipophilicity and lower molecular weight than the parent glycosides [76,77]. The occurrence of biphasic appearance of isoflavones in plasma, as well as in urine, has been reported [18]. The first peak appears at two hours after isoflavones intake and may represent the rapid transformation of glycosides into aglycones. The second peak appears 6–8 h later and could be accounted for 90% of total isoflavones, corresponding to further biotransformation by gut microbiota of unabsorbed isoflavones [78]. Once the aglycones reached the colon, they can be converted into more or less bioactive metabolites than their precursors. For example, daidzein is hydrogenated to dihydrodaidzein and further converted to O-DMA and/or S (−) equol, depending on the presence of specific bacteria strains in the human colon [18]. The S-equol is structurally similar to 17β-estradiol and has a higher estrogenic activity in comparison with daidzein or other isoflavones [79]. In contrast, O-DMA is less similar to endogenous estradiol and consequently has a lower estrogenic activity and seems to be less biological active than S-equol or daidzein [80]. Genistein is first reduced to dihydrogenistein, and then to 6′-hydroxy-O-DMA (6′-OH-O-DMA), which can be degraded to 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-propanoic acid [81]. However, it should be noted that one bacterial strain, Slackia isoflavoniconverten, can convert genistein to 5-hydroxy-S-equol, a compound that shows a higher antioxidant activity than genistein [82]. Notably, some of isoflavone’s metabolites can be reconverted to aglycones in blood, assisted by efflux transporters. While genistein glucuronide can be re-transformed to genistein, the sulfate conjugates cannot be modified [83]. While the formation of S-equol is well documented, little is known regarding the relevance of the degradation of genistein to 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-propanoic acid or to trihydroxybenzene in humans [19].

Formononetin and biochanin A can be demethylated by the intestinal microbiota or by hepatic microsomal enzymes to corresponding free aglycones [39]. Moreover, small amounts of their glucuronide and sulfate metabolites with methoxy group at the 4′-position were identified in plasma and bile of animals and in human cells [84]. In addition, in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that the red clover’s isoflavones have different biological activities in comparison with their demethoxylated aglycones [85].

Not all human individuals harbor intestinal bacteria that are capable of metabolizing daidzein to biological active S-equol [79], whilst the majority of animal species consuming plants rich in isoflavones can produce S-equol [86]. Observational studies showed that only 30% of the Western population is able to produce S-equol, in comparison with the Asian population, where approximatively 60–70% of individuals are S-equol producers [15,87]. Hitherto, several species of bacteria capable of producing S-equol have been identified, including Streptococcus intermedius, Ruminococcus productus, Eggerthella sp. Julong732, Adlercreutzia and Slackia equolifaciens [12,88]; however, the abundance of Asaccharobacter celatus and Slackia isoflavoniconvertens in the individual’s gut microbiota might play a significant role [89]. One study found that a consortium of Lactobacillus mucosae, Enterococcus faecium and Finegoldia magna EPI3 Veillonella sp. was able to produce S-equol in the presence of colonic fermentation products, such as poorly digestible carbohydrates, but not when fructo-oligosaccharides were added in culture [90]. The Clostridium species, which are widespread in human population, are considered to be responsible for isoflavones’ degradation, including daidzein conversion to O-DMA [13]. Interestingly, the probiotic Lactobacilus rhamnosus JCM 2771 has the capacity to produce genistein from daidzin, affecting the production of S-equol [91]. Human dietary-intervention studies using prebiotics or probiotics in order to increase the S-equol production have shown inconsistent results [87].

S-equol first appearance in plasma is at eight hours after isoflavones ingestion and remains present even 48 hours after intake [77]. In humans, plasma or serum levels of free isoflavones are different depending on the duration and the type of diet. Plasma levels of genistein have been reported to be at 7–18 nM in individuals consuming standard Western diets, with a measurably five-times-higher level in individuals consuming vegetarian diets and for high-soy-diet consumers, reaching hundreds of nanomolars [92]. For example, the serum concentration in Japanese postmenopausal women is, on average, 500 nM for genistein, 250 nM for daidzein and 58 nM for S-equol [93]. Importantly, the apparent isoflavones bioavailability is higher in children than adults, higher in healthy people in comparison with individuals with chronic illness and increased in adults who were exposed to isoflavones rich diet during early periods of life [78].

Pharmacokinetics studies of S-equol in animals and humans have proven similar metabolism, including rapid absorption [79]. S-equol has the lowest affinity for serum protein, a high affinity for the estrogen receptors and the highest antioxidant activity of all the isoflavones and their metabolites studied until now. More investigations are needed to characterize the impact of different forms of equol, of racemic equol from commercial nutritive supplements versus intestinal production, as well as the effect of equol conjugates on human health.

3.2. Prenylflavonoids

Hop’s prenylflavonoids have shown a slow to moderate rate of absorption through the intestinal epithelium in animal and human studies [94]. In stomach, chalcone XN can be converted to IX by gastric acid. After that, unaltered XN or IX can reach the small intestine where they accumulate into enterocytes and enter the systemic circulation more slowly than 8-PN [51,94]. In vitro studies have indicated that the phase-II conjugation as glucuronidation and, to lesser extent, sulfation predominates over phase-I metabolism for all tested prenylflavonoids [51]. Moreover, IX can be transformed by liver microsomes to 8-PN at a lower rate, but in the colon this transformation by microbiota is higher, with a conversion efficiency close to 35% [95]. Therefore, the demethylation of IX by the microbiota is the predominant pathway of 8-PN production in humans. The human bacterial strain of Eubacterium limosum has been found responsible for 8-PN production. In germ free rats the intestinal administration of this bacterial strain resulted in an increase of up to 80% in 8-PN production after IX ingestion [96]. Notably, Eubacterium species are also butyrate producers in humans [97], the butyrate being a metabolite capable to act as inhibitor of histone deacetylases, important proteins part of epigenome [98]. Indeed, the particular strain of E. limosum was observed to increase the butyrate production along with 8-PN ones in animal studies [96]. As in the case of daidzein conversion to S-equol, there is an inter-individual variation in humans producing 8-PN from IX. So, individuals can be categorized as poor, moderate and strong producers of 8-PN depending on their phenotypic differences that might affect the pathways of biotransformation of prenylflavonoids [16]. Moreover, the polymorphism of metabolic enzymes can influence the 8-PN biotransformation. For example, enzyme CYP1A2, which is responsible for O-demethylation of IX to generate 8-PN, presents a high genetic polymorphism in human population [23]. As a consequence, the plasma concentration of prenylflavonoids and their metabolites varies between individuals. The 8-PN is the most biological active prenylflavonoid, and its production by human microbiota represents an additional contribution to overall phytoestrogens content in humans after beer ingestion.

The common structure of icariin is 8-prenylkaempferol, with two radicals attached, in which one radical is rhamnose and the other glucose. Removal of rhamnose results in icariside I, while removal of glucose radical produces icariside II. The aglycone form of icariin is icaritin, which can be metabolized into desmethylicaritin by demethylation reaction. In animal models the formation of icariin metabolites depended on the route of administration, icariside II being the main metabolite after oral intake and it is less present if icariin was intravenously administrated [46]. Interestingly, in human studies icariside I was not detected, the only metabolites produced by human bacteria were icariside II, icaritin and desmethylicaritin [99]. Moreover, the pharmacokinetic reports showed a peak of icaritin at 8 h after Epimedium extract intake, suggesting that the conversion of icariin to its aglycone takes place primarily at intestinal level [100]. Indeed, under anaerobic conditions the intestinal bacteria (Streptococus sp. and Enterococcus sp.) transform icariin to icariside II [101], and the Blautia sp. is responsible for producing hydrolyzed metabolites, icaritin and desmethylicaritin, which both exhibit estrogenic properties [99]. The tissues distribution has been studied only in animal models. A dependence of gender was observed, with high accumulation of absorbed icariin in liver and lung of male rats, and in females, the accumulation was mainly in uterus [46]. Nevertheless, more investigations should be made in order to clarify the metabolism of Epimedium bioactive compounds, the plant being considered to have a strong therapeutic potential for human health.

Glabridin is the prenylated isoflavonoid from licorice which binds to the human ER with about the same affinity as genistein [47]. It is highly unstable under basic conditions and has an inhibitory activity on several human cytochrome P450 enzymes [102]. In reconstituted cytochrome P450 isoforms experiments the glabridin inhibition was a time-, concentration-and NADPH-dependent process, with 50% inhibition at 7 and 12 μM concentration [102]. The inhibition was found to be irreversible through dialysis, and for one isoform the inhibition was associated with the destruction of the heme moiety [102]. Moreover, reports showed that the glabridin is a substrate of the intestinal p-glycoprotein P-gp/MCR1 and this along with hepatic glucuronidation could explain its very low bioavailability compared with other phytoestrogens, even in small rodents (7.5%) [103]. Human studies have showed that a dose of standardized licorice extract up to 1200 mg/day for 4 weeks is safe, and pharmacokinetics of glabridin was linear through all investigated period of time [104]. The inactivation of the major cytochrome P450s by glabridin were supposed to be minimal [104], but the presence of other flavonoids in the licorice extract may additively or synergistically inactivate the phase-I enzymes. Despite several documented studies, the pharmacokinetic parameters of glabridin and its metabolism are far from being elucidate, and further studies will be necessary to better define its bioavailability, the existence of potential bioactive metabolites and the precise profile of its P450 interactions.

3.3. Coumestans

There are no systematic studies on coumestans absorption and metabolism in humans, and the few in vivo studies have reported that coumestrol and wedelolactone have low bioavailability in comparison with genistein and daidzein [105,106]. However, the coumestans could go through an intense metabolic process in the human gut, similar to isoflavones. In rats orally feed with wedelolactone for 3 weeks, approximatively 15–20% of wedelolactone was in unconjugated form and an extensive phase-I metabolism was observed [107]. For coumestrol a maximum concentration of unconjugated molecules was detected 4 h after single oral dose, with approximatively of 70 nM/L in plasma of rats which dropped to 15 nM/L almost 8 h after feeding [105]. Moreover, in vitro experiments have revealed that wedelolactone undergoes glucuronidation, methylation, sulfation and oxidative metabolism after 3 h of incubation with rat hepatocytes [107]. Even that wedelolactone has three phenolic hydroxyl groups attached on its skeleton, glucuronate metabolites were preferentially formed [107]. No specific gut metabolites of coumestans have been reported until now, but the future research probably will bring new insides.

3.4. Lignans

The beneficial effect of lignans on human health is stemmed from bioactivities of enterolignans END and ENL which are exclusively produced by the gut microbiota. The END and its oxidation product ENL exert numerous health benefits against breast, colon and prostate cancer, osteoporosis, cardiovascular diseases, hyperlipidemia and menopausal syndrome [108,109]. The complexity and diversity of lignan molecules require a supplemental series of reactions in order to facilitate their absorption in humans, in comparison with flavonoids. In contrast to isoflavones, lignans did not appear in blood immediately after ingestion which suggests a slower rate of absorption and more intense metabolization. Reports based on in vitro experiments, in simulating conditions of the stomach and small intestine, have been showed that lignans such as SDG are resistant to acid hydrolysis [110]. Indeed, the majority of plant lignans suffers marginal alteration during gastric and small intestine passage [111]. However, their deglycosylation may occur via the action of brush border enzymes of small intestine as suggested by the in vivo appearance of SECO in plasma, 5–7 h after the intake of food rich in SDG. Moreover, maximum serum concentrations of END and ENL were attained after 12–24 and 24–36 h, respectively [112]. Therefore, a little amount of aglycones is absorbed in small intestine, with a significant portion of ingested lignans reaching the large intestine for further transformation by the local microbiota [17]. The lignans metabolism has proved to be a multiple-step process catalyzed by a diversity of microbacterial strains. In vitro fermentation experiments with human bacteria species and in vivo studies including dietary interventions in humans have identified a consortium of at least 28 species of bacteria involved in enterolignans production [17,71]. For example, the initial step of SDG metabolism, the deglycosylation can be catalysed by three Bacteroides sp. (B. distasonis, B. fragilis and B. ovatus) and two strains of Clostridium (C. cocleatum and C. saccharogumia) [113]. Demethylation of its aglycone requires other bacterial strains, including Butyribacterium methylotrophicum, Eubacterium (E. callanderi and E. limosum), Blautia producta and Peptostreptococcus productus [88,111]. Dehydroxylation of SECO is catalysed by Clostridium scindens and Eggerthella lenta and the dehydrogenation of END to ENL, and closure of the lactone ring involves bacterial strain of Lactonifactor longoviformis [[88,111]. In general, the diglucosides or glycated lignans are following the multi steps metabolism of SDG and for most of them SECO is the intermediate aglycone form. The transformation of arctiin, to its aglycon arctigenin, and then to ENL requires an extra demethylation reaction [17]. Interestingly, the bacteria Ruminococcus R. sp. END-1 isolated from human has been able to oxidize enantioselectively (−)-END to (−)-ENL. Moreover, the bacterial strain showed demethylation and deglycosylation activities, and by co-incubation with Eggerthella sp. SDG-2 were able to transform arctiin and SDG to (−)-ENL and (+)-END, respectively [114]. Although lignans are widely present in human diet, only few of them can be converted with high efficiency into enterolignans, mainly those with lactone and furan-based structures [115,116]. MAT, LARI and PINO have similar rate of conversion, around 55–65%, in comparison with SDG and SECO which have the highest rate of conversion [115]. In contrast isolariciresinol, also a flaxseed lignan is not converted to either END or ENL [115]. Notably, the bacterial strains capable to generate enterolignans are generally widespread in human population, so no significant inter-population variability has been observed, as in the case of S-equol or 8-PN production. The main factors controlling the plant lignan’s bioactivation in humans are diet, transit time, intestinal redox state and drugs uptake. All these can affect the composition of microbiota and the activities of bacterial strains responsible for enterolignans production [17,106]. Importantly, the microbial dehydrogenation of END to generate ENL is the crucial step in dietary lignans metabolism and the shift toward a major production of ENL is desirable because its stronger association with health benefits [17]. Serum or urinary ENL concentration varies considerably in humans depending mainly on dietary preference and ranges typically between 0.1 and 10 μM [117]. There is a relatively limited information of their tissue distribution and largely it comes from preclinical evaluations of rodent models. In general, all dietary phytoestrogens and their metabolites accumulate in highly perfused tissues such as the liver, intestine, kidney and lung and are present predominantly in their conjugated forms [118]. The preclinical data on mice and rats have revealed that liver contains the majority of the tissue lignans, approximatively 55% of total absorbed lignans. After prolonged exposure to SDG, the concentrations of lignans in skin and kidneys have increased, indicating tissue accumulation. For females, a higher lignan concentrations in heart and thymus has been observed [119]. Moreover, other reports had shown that flaxseed lignans co-administrated with isoflavones can produce more END in plasma than daidzein, and the enterolignans were also present in prostate and breast tissues [119]. Furthermore, clinical studies have demonstrated that the levels of ENL in cancer-free patients are significantly higher than those measured in patients with breast cancer [63,109]. This observation along with other evidence strongly suggests that stable ENL levels can be associated with a reduced risk of hormone-dependent cancers [108,120].

3.5. Stilbenes

Resveratrol is a lipid-soluble compound with a high cellular membrane permeability, but its low water solubility (< 0.05 mg/mL) affects its oral bioavailability [121]. Even though its systemic bioavailability is low, detectable level of resveratrol in epithelial cells along aerodigestive tract has been observed [122]. At intestinal level, resveratrol can undergo passive diffusion or can bind to membrane transporters [121]. If it is present in bloodstream as free molecule, almost 90% of them can form complexes with albumin and lipoproteins based on in vitro and in vivo experiments and human studies [123]. However, these complexes can be dissociated by cellular receptors of albumin and lipoproteins allowing free resveratrol to pass cellular membranes and so to improve its absorption and tissue distribution. The stilbenes are present in wine and grape juice, mainly as trans-piceid, a glycosidic compound [66]. Whilst trans-resveratrol can passively diffuse the cell membrane, trans-piceid has seen accumulating in cells and tissues to a lesser extent, due to the presence of its sugar radical. Just after passing the brush border membrane, trans-piceid is hydrolyzed by cytosolic or bacterial β-glucosidases releasing trans-resveratrol [124]. An extremely rapid resveratrol conjugation takes place in the intestine and liver, and this intense metabolism seems to be the rate-limiting step of resveratrol’s bioavailability. More than 20 of its derived metabolites have been identified in animals and humans being produced by the major metabolic pathways [125]. The glucuronide and sulphate conjugates from phase-II metabolism are the most abundant [122,125]. Their plasma levels were reported to be higher compared with the ingested resveratrol, according with data from animal and in human studies [21]. The most studied is resveratrol’s reduced derivate, dihydro-resveratrol (DHR), which has a double bond hydrogenated placed between the two phenolic rings. In addition to DHR, two other metabolites have also been identified in human urine: 3,4′-dihydroxy-trans-stilbene and 3,4′-dihydroxybibenzyl (lunularin) [14]. As in the case of the other phytoestrogens there is a large variation between individuals, some are exclusively lunularin or DHR producers, and others are capable to produce both metabolites, and they are called mixed producers [14]. In vitro fermentation experiments have associated the lunularin producers with a higher abundance of Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Verrucomicrobia and Cyanobacteria species and individuals with a lower abundance of Firmicutes could be either DHR or mixed producers [14]. Two bacterial strains Slackia equolifaciens and Adlercreutzia equolifaciens, which can produce S-equol from daidzein, have been found to be able to convert trans-resveratrol to DHR [14]. The biological activities of resveratrol metabolites have recently begun to be investigated and DHR seems to be more effective antioxidant than Vitamin E analogue, Trolox [126]. Further studies of resveratrol metabolism and the biological relevance of its metabolites are considered to be crucial for elucidating the mechanism behind resveratrol health benefits.

Another interesting resveratrol metabolite is piceatannol, which is resulting from hydroxylation reaction catalyzed by phase-I enzymes in liver microsomes and human lymphoblasts [127]. Additionally, piceatannol can be taken directly from diet, being present in high amount in fruits, including grapes, and white tea [67]. Furthermore, following resveratrol administration in mice models the piceatannol was present in high amount as resveratrol metabolite in plasma, skin, and liver tissues [128]. Moreover, after 5 weeks of resveratrol intake, piceatannol was found as a product of phase-I metabolism in the small intestine of mice [129]. The piceatannol is more stable than resveratrol during metabolism probably due to the presence of an additional hydroxyl group located at the 3′-carbon. Furthermore, piceatannol has similar biological effects as resveratrol, and some data have shown that is more potent than its precursor [68].

Pterostilbene has a higher bioavailability compared to resveratrol (80% versus 20%) due to the presence of two methoxy groups on its structure, which confers an increased lipophilicity and a better oral absorption [69]. Notably, pterostilbene through phase-II conjugation is transformed mainly in sulfate metabolites [130]. Using human liver microsomes to assess resveratrol and pterostilbene glucuronidation, most pterostilbene (75%) was unchanged in comparison with 32% of resveratrol which remained unconjugated [131]. Pterostilbene has shown suitable pharmacokinetic parameters with no significant toxic effects. Moreover, a high content of pterostilbene has been detected in various tissues, including in brain, proving that it has good blood–brain partition coefficient [69]. Overall, the bioavailability and organs and tissues’ distribution of pterostilbene is higher than resveratrol; thus, it can be considered to be a more bioactive molecule even at a low blood and plasma concentration.

All the aforementioned compounds with existing Chemical Abstracts Services (CAS) numbers are listed in Table S1, available in the Supplementary Materials section.

4. The Relationship between Dietary Phytoestrogens and Gut Microbiota: Impact on Human Health

The association between dietary patterns and prevention of disease is probably due to the biological effects (either synergistic or cumulative) of the various components from diet. A number of interrelated biological processes, such as inflammation or immune function, microbiome and metabolites profiles, epigenetic mechanisms, oxidative stress, and metabolic and hormonal responses, have been reported to be modulated by specific diet constituents [2]. The impact of dietary patterns on these biological mechanisms just started to be characterized, and the accumulating evidence suggests that bioactive nutrients can modulate them and consequently can influence human health [2,3,7].

As presented in the previous section, each class of phytoestrogens can be transformed by gut microbiota generating bioactive metabolites and some of them will exert different or stronger biological activities than their parent precursors [85]. In terms of estrogenic capacity of ingested phytoestrogens, their bioconversion may increase the estrogenic potency up to tens or hundreds of times. Regularly, the human diet contains only small amounts of prenylflavonoids, such as 8-PN, but gut microbiota can transform an amount of 4 mg/L of IX (from beer) into 8-PN, resulting in a approximatively 100 times higher exposure of the host to estrogenic metabolites [132]. A diet rich in lignans can expose individuals to up to 75 times to more bioactive metabolites as enterolignans, with potential estrogenic activity [132]. Ingestion of 13.5 g of flaxseed per day for 6 weeks has been reported to lead to micromolar concentrations of ENL and END conjugates in human plasma, being up to 1000–10,000 times higher than the plasma level of the circulating endogenous estrogens [106,116]. Although phytoestrogens are acting as weaker estrogens or anti-estrogenic compounds, their plasma concentrations can be three times higher than endogenous estradiol after daily consumption of two meals based on soy products [133]. In this case, the dietary phytoestrogens more likely may act as endocrine-disrupting agents, inducing negative effects on human health. Therefore, it is important to know the content of phytoestrogens in human diet, and how the phytoestrogens and their metabolites can influence biological processes in human body. In addition to estrogenic or anti-estrogenic activities, phytoestrogens might exert beneficial antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antitumor activities, yet the knowledge of possible adverse effects induced by the ingested amount are required. Thus, the content of phytoestrogens from our daily meals should be known, and in the next section, we present the latest information about total phytoestrogens amount from some dietary sources.

4.1. The Content of Phytoestrogens in Food

More than 300 phytoestrogens have been detected in a large range of legumes, vegetables, fruits and berries, cereals, nuts, alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverage, as well as in processed food products or dairy products [4,5,37]. The phytoestrogens content in raw food varies substantially, being typically as low as a few micrograms per 100 g, yet sometimes can reach levels of hundreds of milligrams per 100 g, as presented in Table 1. It is boteworthy that the reported data are in a broad range mainly because of different methods used for quantification of each class of phytoestrogens. Moreover, as mentioned before the plants are producing phytoestrogens in variable quantities depending on stress conditions and cultivars [31]. Moreover, the data on the content of coumestans, prenylflavonoids and stilbenes in raw or processed food are rather limited, and more information is needed in this regard.

Table 1.

Dietary source of phytoestrogens (mg/100 g or mg/100 mL).

As Table 1 shows, one food source can contain several classes of phytoestrogens, yet other phytochemicals with biologic activities are presumed to be present. Whole soybean can contain large amounts of isoflavones, along with coumestans and lignans [4]. The flax and sesame seeds have the highest concentration of lignans, mainly SDG and sesamin, but also isoflavones and traces of coumestans [134,135]. Notably, relatively large quantities of phytoestrogens have been found in dairy products, mostly microbiota’s metabolites such as S-equol and ENL from cattle feed with red clover and forages rich in lignans [71]. When feeding cattle with red clover, the level of S-equol in milk can range between 15 and 650 g/L; moreover, larger quantities of S-equol were identified in organic milk in comparison with conventionally produced milk [5,6].

An extensive European study has described the phytoestrogens intake and the food sources, highlighting their variability in European diet as depending on regions and lifestyle characteristics [9]. In the Mediterranean diet, which is considered to be the healthiest one, the main contributing dietary phytoestrogens were lignans (58.1–67.3%), isoflavones (30.4–37.9%) and coumestans (1.5–3.3%), followed by enterolactone (0.7–0.8%) and S-equol (0.2–0.3%) from dairy products [9]. In Europe, USA and Canada, the consumption of phytoestrogens comes mainly from tea, coffee, wine, fruits, and vegetables with an average intake of 2 mg/day [19]. Whilst, in Asian populations isoflavones from soy-based food and lignans from green tea are the main source of phytoestrogens, with a daily intake from 16 to 70 mg/day, but sometimes can reach 120 mg/day [42].

As mentioned, the food matrices have strong influence on the absorption of phytoestrogens [81]. They are present mostly in glycosidic forms in raw food, so are being less absorbed in humans [76,112]. Western diet consumers are eating more non-fermented soy products, such as soy milk and tofu containing primarily the glycosidic isoflavones, whilst in traditional Asian diet predominates the fermented soy products with high content of aglycones, which are absorbed rapidly [4]. Moreover, the simple preparation of food can destroy the chemical structures of phytoestrogens and consequently alter their biological activity. For lignans, a high roasting temperature had caused degradation of both aglycone and glycosidic structures of rye and sesame seeds [138]. To conserve the nutritionally content of lignans during production of processed foods, several aspects should be taken into consideration such as their chemical structures, water content and the applied temperatures [138]. Whether mixtures of phytoestrogens present in daily meals at relevant doses can synergize or antagonize with endogenous estrogens is still under debate, yet the important role of the gut microbiota with regard to the bioavailability and bioactivity of phytoestrogens just started to be unveiled [132,139].

4.2. Reciprocal Modulation between Dietary Phytoestrogens and Gut Microbiota

The community of microorganisms populating human guts represents microbiota and their collective genomes form the microbiome which encodes a number of genes with more than 100 times larger than human genome [140]. Moreover, the microbiome of two different individuals is highly different compared to their genomic variation; thus, the genome identity in humans is about 99.9% [141], and gut microbiome can be just up to 10–20% identical [142]. Diet composition has a definite role in the taxonomic and functional profile of the microbiota, and it consequently influences the microbiome. Furthermore, many dietary components are metabolized by commensal or symbiotic gut microbes into bioactive molecules that could support cellular mechanisms for disease prevention. Increasing evidence suggests that the gut microbiome can influence chronic disease predisposition and has a definite role for maintaining the well-being of individuals [2]. A plant-based diet can induce the development of diverse and more stable microbial strains with a favorable impact on human health. Phytoestrogens, as well as plant polyphenols, have increased Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus population in human guts, which can induce anti-pathogenic and anti-inflammatory effects, along with cardiovascular protection [11]. Interventional studies have also established that changing from a carnivorous diet to a plant-based one is resulting in a gradual decrease in abundance of Alistipes, Bilophila and Bacteroides, as well as all bile-tolerant symbiotic microorganisms; and an increase in Firmicutes, which preferentially metabolizes plant polysaccharides [11]. Importantly, the Firmicutes species are responsible for converting trans-resveratrol to lunularin [14]. By assuming a short-term consumption of diets based exclusively on animal or plant products, the microbial community structure can be rapidly altered, and thus the overall microbial gene expression is changed with impact on human health [143]. Therefore, a diet should be balanced, containing different nutritional components able to support the needs of a healthy human body.

The consumption of phytoestrogens can modulate the gut microbiota composition. A variation in microflora species between S-equol and non-S-equol producers has been observed in several human studies [13]. In addition, an association of S-equol production with the quantitative increase of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Lactobacillus–Enterococcus, which are two dominant species of human colonic bacteria, is indicating that some phytoestrogens might selectively modulate intestinal environment through their metabolites [13]. Recent data have shown that a diet enriched in fibers (e.g., flaxseed gums) induces an anti-obesity effect, along with alteration of microflora community in obese rats and mice [144,145]. The lignan based diet has decreased the relative abundance of Clostridiales, and enriched the colonic microbiota with species such as Clostridium and Enterobacteriaceae [144]. The anti-obesity effect in mice has been associated with an increased abundance of the Clostridia genus, which is capable of producing a high level of butyrate [145]. The resulting shift in gut microbiota composition has restored the necessary levels of butyrate and lactic acid, leading to the modulation of gene expression of colonic enteroendocrine cells [145]. Lignan-based diets have improved the colon health, and as several in vivo and interventional studies have demonstrated, they have induced the modulation of gut microbial structure and increased the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) [13]. Similar to lignans, the stilbenes intake can modulate gut microbiota composition, specifically by increasing the ratio of Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes species, along with decreasing the abundance of Clostridium genus and Lachnospiraceae family [146]. Along with gut modulation, a decrease of expression of genes involved in fatty acid synthesis, lipogenesis and adipogenesis; improved carbohydrate metabolism; glucose homeostasis; and lower diabetes risk can be achieved [146,147]. However, there are in vivo studies which have reported no impact of resveratrol supplementation on the ratio of Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes species, and yet the bioactivity of resveratrol on metabolic syndromes has been observed [148].

Moreover, phytoestrogens, as phenolic compounds, may have antimicrobial activity and can interact with the pathogen bacterial strains [149]. Consequently, they might modulate the diversity of the colonic microflora by inhibiting the pathogens, or by increasing the beneficial bacterial populations, thus contributing to the improved health of the individual.

Convincing evidence to support a link between diet and microbiome in cancer prevention comes from studies on dietary patterns with a high intake of fibers. Dietary fibers undergo bacterial fermentation in the colon to yield butyrate, which acts as a histone deacetylase inhibitor and is able to suppress the growth of colorectal cancer cells in vitro [150]. High fiber intake also encourages the growth of bacteria species that can transform the fibers into other SCFAs, such as acetate and propionate, which, along with butyrate, have an impact on human epigenome [151,152]. As mentioned, the Eubacterium limosum strain converts IX to 8-PN [95], but it is capable of producing butyrate in humans [97]. The SCFAs have positive health effects, such as improved immunity response, blood–brain barrier integrity, provision of energy substrates, intestine homeostasis and epigenome modulation [11]. Furthermore, the SCFAs can act as endogenous ligands for two group of orphan G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), also known as free fatty acid receptors (FFARs). The discovery of SCFAs’ capacity to bind and activate FFAR2/GPR43 and FFAR3/GPR41 unveiled the multiple ways of which metabolism and immune system are interconnected [153]. These two free fatty acid receptors are expressed in several human cell types related to the immune system, adipose tissues, gut and in pancreatic β-cells [154]. Moreover, FFAR3/GPR41 appears to be highly expressed in the neurons of sympathetic and enteric nervous system, where upon activation by SCFAs accumulating in the intestine, FFAR3/GPR41 can be signaling to the brain via neural circuits to regulate intestinal gluconeogenesis [154]. Functional expression of FFARs in the nervous system implies a possible connection between nutritional status and autonomic nervous system function. These recent findings demonstrate that free fatty acid receptors might mediate the beneficial effects of SCFAs, with an impact on intestinal homeostasis, energy metabolism, immune system function and neuronal signaling.

Furthermore, phytoestrogens have a direct influence on the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), which is an important factor in intestinal homeostasis [155]. The AhR, known as a ligand-activated transcription factor, is able to integrate microbial and gut metabolites’ signals, along with environmental and dietary stimuli into complex transcriptional networks in a cell-type and context-specific approach [156]. Isoflavones are natural ligands of AhR, with biochanin A and formononetin having the more potent agonist activities [157]. Moreover, prenylated flavonoids, such as icaritin, 6-PN and 8-PN, but not IX, are exhibiting a unique agonist potential in comparison with their parent precursors by selective upregulation of the P450 1A1-mediated estrogen detoxification pathway [158]. Phytoestrogens can produce ligands for AhR, therefore connecting gut lumen environment and cellular processes with the impact on human health by activating cyto-protective and antioxidant responses [159].

In conclusion, the phytoestrogens-based diet might exert health benefits or adverse effects to the host via modulation of gut microbiota. Likewise, the gut microbiota can influence the phytoestrogen metabolites production, with impact on human health, as Figure 2 shows.

Figure 2.

Reciprocal modulation between dietary phytoestrogens and gut microbiota.

In-depth studies to identify new colonic microbes and their enzymes involved in the metabolism of each class of phytoestrogens are critical for understanding their beneficial or adverse effects on human health. Moreover, the synergistic or cumulative effects that can be induced by different types of phytoestrogens absorbed in human body should be studied, both in terms of modulating the bacterial microflora and their influence on different cellular processes.

5. Epigenetic Modulator Capacity of Dietary Phytoestrogens

Dietary phytoestrogens and their metabolites are known for their capacity to interact with estrogen receptors, which are expressed widely in the human cells; however, other important biological activities have been highlighted [7,24,63]. The major mode of action by which phytoestrogens exert their possible health effects is based on their estrogenic or anti-estrogenic activity by binding to estrogen receptors. In Table 2, we present several dietary phytoestrogens which are able to imodulate estrogen-depending signaling pathways.

Table 2.

Estrogenic effects of dietary phytoestrogens.

Resveratrol metabolites could be more efficient antioxidants than their precursors [126], and the prenylflavonoids can induce an antioxidant response much stronger than parent isoflavones [158]. Coumestrol is considered the most potent phytoestrogen, and in addition, its antioxidant activity is considerably higher than genistein and daidzein [57]. Moreover, S-equol has a strong affinity for estrogen receptors and also the highest antioxidant activity among isoflavones [79]. Recently, in a study on adults’ lignans consumption, ENL and END levels from plasma have been inversely associated with markers of chronic inflammation, such as C-reactive protein [174]. The mechanisms underlying the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of phytoestrogens are still being investigated [139], but scientific evidence in recent years interconnected these properties with the potential ability of phytoestrogens to act as epigenetic modulators [7,175]. Epigenetic mechanisms control gene expression, and by modulating one mechanism, phytoestrogens can act on several genes and thus can influence signaling pathways and complex cellular processes. Mainly, the phytoestrogens are affecting the activities of proteins part of epigenome regulatory mechanism, including DNA-methyltransferases (DNMTs), DNA-demethylases (TETs, TDGs), histone deacetylases (HDACs), histone-acetylases (HATs), histone methyltransferases (HMTs) and histone demethylases (HDMs) [25,26,176]. The DNA methylation process is carried out by DNMTs and occurs at CpG islands, which are short DNA sequences located at gene promoters or in noncoding regions scattered throughout the genome. DNMT3A and DNMT3B proteins catalyze the addition of a methyl group to cytosine at five positions (5-mC), whilst DNMT1 maintains the somatic inheritance of DNA methylation during cell division [26].

Combinations of histone post-translational modifications are able to signal different modifications on chromatin regions and create transcriptionally activated or repressed gene expression sites [177]. Although the epigenome has not been completely elucidated, histones’ lysine’s acetylation (H3K9ac, H3K14ac and H4K16ac) and trimethylation (H3K4me3) are able to establish transcriptionally active sites; instead, H3K9me3, H3K27me3 and H4K20me1 are signaling the silencing of gene expression [177,178]. The heterochromatin regions can become unpacked when the positive charge of the lysine residues from histone tails are acetylated by HATs. As a consequence, the chromatin accessibility to transcription factors and RNA polymerase II increases, resulting in gene expression. On the other hand, HDACs can restore the compact chromatin by erasing the histone acetylated marks. Deacetylation of a lysine residue from histones may allow its further modification by HMTs, and also intermediate the recruitment of DNMTs for reinforcing the close chromatin status. Together, these epigenetic changes will enable a progressive decrease in the accessibility of DNA to the transcription machinery and hence an increasing transcriptional silencing [25].

Several classes of HDACs are using histones, as well as non-histone proteins as substrate for deacetylation reaction. A particular class of HDACs, the sirtuins family, possesses two enzymatic activities, namely mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase and NAD+ dependent deacetylase, and is involved in the regulation of many cellular processes [179]. One of the most remarkable members of sirtuins family is SIRT1, which can deacetylate both histones and a wide range of non-histone proteins. SIRT1 has a preference to deacetylate the lysine 16 of histone H4 (H4K16ac). This epigenetic mark has been linked to the regulation of cell-cycle progression, active transcription, DNA repair and DNA replication [180]. Moreover, hypoacetylation of H4K16, along with hypomethylation of H4K20, has been proposed as a hallmark of human cancers [181]. By exercising its deacetylation activity, SIRT1 acts as a chromatin modifier, transcriptional regulator and metabolic regulator. Thus, it modulates important cellular functions, such as apoptosis, cell growth, cellular senescence, oxidative stress response, metabolism and tumorigenesis [179,180].

Another layer of epigenetic mechanism with an impact on gene expression is represented by small and long non-coding RNAs (microRNAs and lncRNAs) which are able to modulate gene expression without changing DNA sequences. Noncoding RNAs are not translated into proteins, being considered part of the regulatory mechanism of gene expression at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. Notably, the expression of non coding RNAs is under the control of epigenetic regulation mechanisms, including DNA methylation, RNA modification and post-translational modification of histone [182,183]. MicroRNAa (miRNAs) are short RNA sequences with ∼22 nucleotides of lengths, which are acting as epigenetic modulators, by affecting the protein levels of the target mRNAs without modifying the gene sequences [182]. They can bind to target messenger RNAs (mRNAs) through nucleotide complementarity, after which the protein translation is terminated by its mRNA degradation. MiRNAs are considered to be the fine-tuning regulators of protein expression, which can establish the timing and the level of specific protein expression.

The lncRNAs are RNA transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides that are considered to be important regulators of the epigenome. Their molecular mechanism of action depends on cellular localization and the type of interacting molecules; thereby, lncRNAs can be classified as signal, decoy, guides or scaffold [183]. Signal lncRNAs regulate transcriptional activity or signaling initiation, whilst decoy lncRNAs bind and titrate out gene regulatory elements, such as proteins, mRNAs and miRNAs. Nuclear lncRNAs can bind transcription factors or chromatin modifiers proteins (e.g., DNMTs, HATs, HDACs and PcGs), whereas, in the cytoplasm, they function as a sponge to attract proteins and miRNA/RISC complexes away from their targets [183,184]. Acting as scaffolds, lncRNAs can coordinate the formation of distinct epigenetic regulatory complexes on specific chromatin regions, dictating their active or inactive transcriptional status. They have the ability to guide protein complexes to both close and distant genomic loci which allow them to regulate gene expression on a genome-wide scale [184]. In conclusion, as epigenetic modulators, lncRNAs can increase or repress transcriptional activity by controlling the deposition of histone marks and DNA methylation pattern on chromatin regions. The reciprocal interconnection of non-coding RNAs with epigenetic pathways appears to form a feedback loop that have an extensive influence on gene expression throughout the genome. Therefore, any dysregulation may affect physiological and pathological processes and will contribute to a variety of diseases.

Emerging scientific data suggest that a diet rich in vegetables and fruits can significantly reduce the risk of chronic disease development, due to the action of nutrition bioactive constituents, which can regulate the gene expression [176,185]. Remarkably, many phytochemicals, including phytoestrogens, may act through epigenetic mechanisms, such as modulation of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), histone deacetylases (HDACs) activities and non-coding RNA expression [24,30,176]. In the next sections, the epigenetic modulator capacity of phytoestrogens and of their metabolites is presented, underlining their mode of action with effect on different biological processes.

5.1. Isoflavones

Isoflavones have been intensely studied in connection with their epigenetic modulator potential in chronic diseases, especially in cancers. Genistein is acting as a chemotherapeutic agent in various cancer cells, modulating cell proliferation, apoptosis and metastasis [186]. Indeed, anticancer properties of genistein have been associated with re-expression of tumor-suppressor genes that were methylation-silenced during carcinogenesis [175,187]. For instance, genistein reversed hypermethylation of ATM, APC, BRCA1 and PTEN tumor-suppressor genes and restored the ER expression in ER positive and triple-negative breast cancer cells by inhibiting the DNMTs’ activities [188,189]. In general, the BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations imply a high risk of breast and ovarian cancers, yet their epigenetically silenced promoters are found frequently in many types of cancers [189]. Moreover, in the case of ER positive cells, genistein epigenetically had re-expressed BRCA1, but also acted as antagonist of AhR [190]. In addition, genistein and daidzein treatment of breast cancer cells decreased the expression levels of MeCP2 protein [191], which have a methyl-CpG-binding (MBD) domain that recognizes and binds to 5-mC regions of DNA. The daidzein gut metabolite, S-equol, at physiological concentration of 2 µM and after long-term treatment, was acting as demethylation agent of BRCA1 and 2 promoters in breast cancer cells but not in normal mammary gland cell line [192]. In general, isoflavones have shown DNA demethylating capacity, with genistein as the most potent among tested isoflavones, by reducing the promoter methylation of genes involved in preventing cancer development [187,190,191,193,194].

The epigenetic modulation capacity of isoflavones has been observed in correlation with histone posttranslational modifications. Thus, genistein treatment can affect different epigenome modifier proteins, including histone deacetylase (HDACs) and histone H3 Lys 9 methyltransferase (HMT) by reducing their enzymatic activities in cervical cancer cells [194]. The two most studies isoflavones (genistein and daidzein) and the metabolite S-equol have been reported to demethylate transcriptional repression marks, such as H3K9me3 and H3K27me3, concomitant with modulating the EZH2 protein expression, which is controlling and maintaining the repressed chromatin status in breast cancer cells [195]. Moreover, epigenetic marks, such as H3K4ac and H4K8ac, signaling the active chromatin, became hyper-acetylated, accompanied by increased expression of transcriptional activators P300 and SRC3 [195]. Another study reported that genistein alone or in combination with trichostatin A can reactivate ERα expression in the ER negative cells. An enhancement of ERα expression and increased global H3K9, H3 and H4 acetylation, along with decreased DNMT1 expression and HDAC activity, were observed [196]. Furthermore, mice exposed to a long-term genistein diet resulted in having a high expression of ERα in spontaneous breast tumors, preventing the occurrence of a more aggressive ER-negative type of breast cancer [196]. The protective effect of genistein can be assumed to be at least in part due to its epigenetic modulator capacity, since HDACs activity was significantly reduced in mice breast tumors [196]. Studies on genistein treatment of precancerous and fully developed breast cancer cells have shown an increased expression of tumor-suppressor genes p16 and p21 through enrichment of transcriptional active markers, such as acetyl-H3, acetyl-H4 and H3K4me3 [188]. Moreover, genistein induced a stronger anti-proliferative effect and pro-apoptotic response in precancerous cells than in breast cancer cells [188], which might suggest that its anticancer properties could be more effective at an early stage of tumorigenesis. In addition, the genistein-enriched diet has prevented tumorigenesis and inhibited cancer development in breast-cancer mice xenografts [188]. Isoflavones can modulate miRNAs expression with impact on their anticancer activity. In vitro studies have demonstrated that onco-miRNAs expression, such as miR-155, can be significantly reduced by treating breast cancer cells with physiological concentration of 1–10 µM genistein [197]. Conversely, the expression levels of miR-155 targets were upregulated in response to genistein treatment, including pro-apoptotic and anti-proliferative proteins: FOXO3, PTEN, casein kinase and p27 [197]. Recently, Lynch et al. have demonstrated that the long-term treatment of PC3 prostate cancer cell line with 40 µM genistein has induced hypomethylation of miR-200c gene/cluster resulting in increased expression of miR-200c [198]. Furthermore, genistein can modulate the expression of tumor-suppressor Smad4 in prostate cancer cell lines via multiple epigenetic mechanisms. Thus, genistein can downregulate miR-1260b that targets Smad4, or genistein can induce DNA methylation and histone modifications at Smad4 gene promoter in prostate and renal cancer cells [199,200].