The Self-Administered Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Supplements and Antioxidants in Cancer Therapy and the Critical Role of Nrf-2—A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

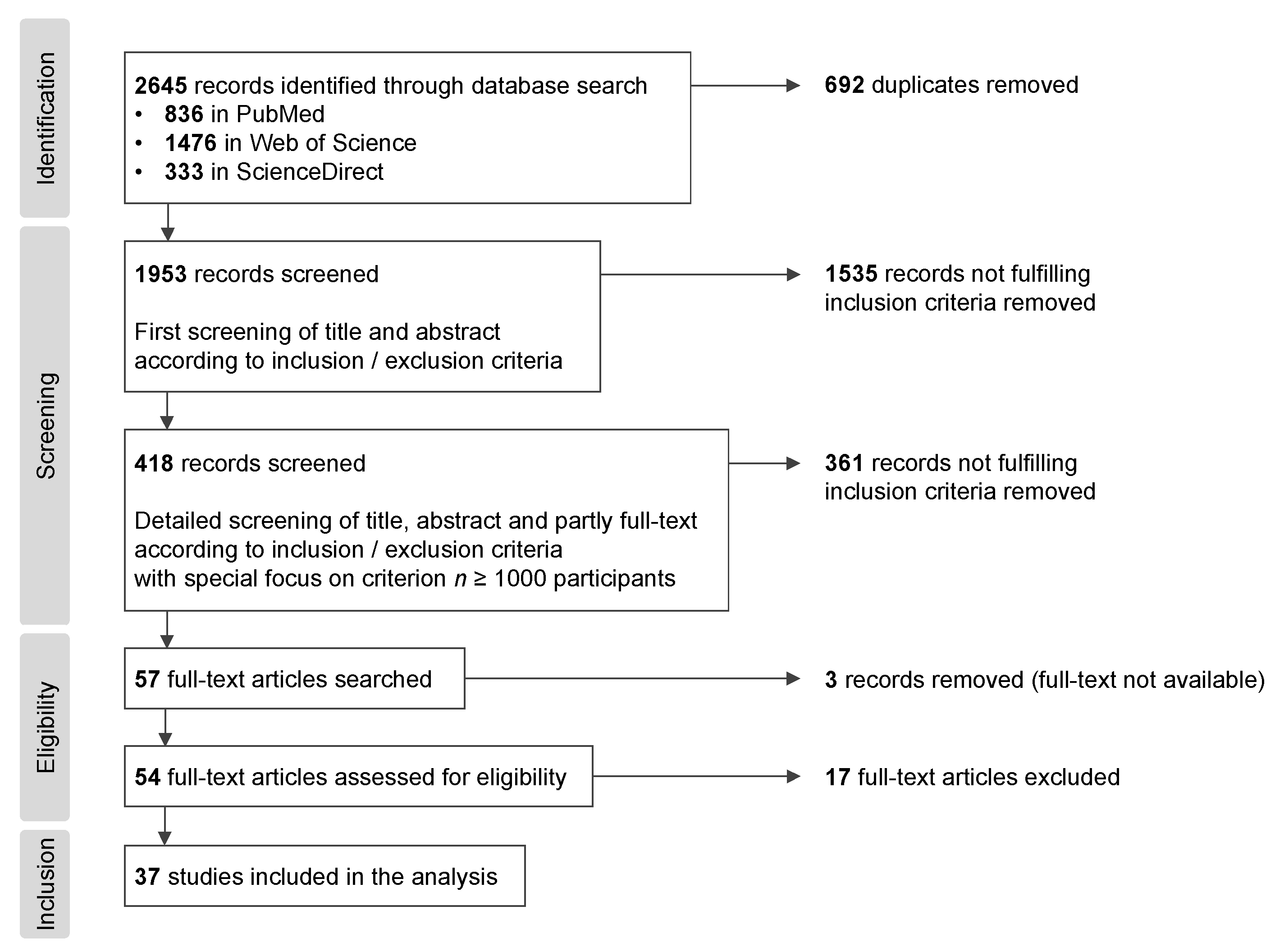

2. Systematic Review on the Self-Administered Use of CAM Supplements and Antioxidants by Cancer Patients

2.1. Materials and Methods

- They focused on the use of CAM providers, modalities requiring a skilled practitioner, or treatments administered by non-medical personnel;

- They investigated dietary patterns, dietary intake (of vitamins and antioxidants), or nutrient status;

- They investigated dietary supplements as a therapy or an intervention in a clinical trial;

- They administered oral nutritional supplements (ONSs) as part of treatment to prevent malnutrition;

- They investigated dietary supplement use in relation to cancer risk or incidence;

- Participants were not cancer patients/survivors (e.g., persons with high cancer risk);

- Information on CAM use was not retrieved from participants (e.g., if it derived from medical records instead of surveys);

- Surveys were conducted with oncologists, nurses, or healthcare professionals (not cancer patients).

2.2. Results and Discussion

| Author | Study Type, Study/Cohort, Participants, Country | Population | Treatment | CAM Use | Dietary Supplement/Vitamin Use | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PART A | |||||||

| Chen et al. [55] | Survey in a cohort study SBCSS 5046 China | Women with breast cancer Average age [a]: 54 years | Chemotherapy: 91.1% of participants Hormone therapy (tamoxifen): 51.9% Radiotherapy: 32.1% | CAM use after diagnosis: 97.2% of participants | Supplement use after diagnosis: 77.2% of participants Melatonin: 0.6% Vitamins: 36.7% | ||

| Conway et al. [62] | Cross-sectional study ASCOT 1049 United Kingdom | Cancer patients recruited from National Health Service sites 38% male, 62% female Mean age: 64 years | Dietary supplement use (24 h dietary recall): 40.0% of participants Multivitamins/minerals: 8.3% Turmeric: 1.9% Vitamin C: 2.6% Vitamin D: 7.7% | ||||

| Greenlee et al. [53] | Cohort study Pathways 1000 United States | Women with breast cancer Average age [a]: 60 years | Treatment received 4 to 6 months after diagnosis Chemotherapy: 44.0% of participants Hormone therapy: 40.3% Radiotherapy: 34.3% Surgery: 97.2% | CAM use history: 96.5% of participants CAM use between diagnosis and study enrolment: 86.1% | CAM product use between diagnosis and study enrolment Herbal and botanical supplements [b]: 47.5% of participants Green tea: 40.9% Omega-3 fatty acids: 33.7% Botanicals or other natural products [c]: 63.8% of participants who received chemotherapy | ||

| Greenlee et al. [54] | Cohort study Pathways 2596 United States | Women with breast cancer Median age [a]: 61 years | Vitamin/mineral supplement use after diagnosis: 82.0% of participants Beta-carotene: 1.7% Multivitamins: 60.8% Selenium: 3.1% Vitamin A: 3.1% Vitamin C: 24.7% Vitamin D: 43.1% Vitamin E: 11.6% | Average doses of vitamin/mineral supplements excessed IOM dietary reference intakes by far notable increases in the mean consumption of certain vitamin/mineral supplements after diagnoses among continuous users | |||

| Huang et al. [56] | Survey in a cohort study SBCSS 1047 China | Women with breast cancer Mean age [a]: 54 years | Former treatment Chemotherapy: 93.1% of participants Hormone therapy (tamoxifen): 47.5% Radiotherapy: 33.0% Surgery: 99.5% | Regular [d] supplement use Multivitamins: 10.5% of participants Vitamin A: 1.2% Vitamin C: 6.5% Vitamin D: 0.6% Vitamin E: 2.9% | |||

| John et al. [63] | Cross-sectional study NHIS 2012 2977 [e] United States | Cancer survivors39% male, 61% female | CAM use during past 12 months CAM (other than vitamins/minerals): 37.9% of participants CAM and/or vitamins/minerals: 78.5% | Vitamins and mineral use during past 12 months: 40.5% of participants | Cancer survivors were more likely to report use of CAM therapies including vitamins/minerals than cancer-free individuals | ||

| Kristoffersen et al. [64] | Survey in a cohort study Tromsø study 2015–2016 1636 [e] Norway | Cancer patients and survivors 47% male, 52% female Mean age: 68 years (patients) and 65 years (survivors) | CAM [f] use during past 12 months: 29.0% of participants | CAM supplement use during past 12 months Herbal medicines/natural/herbal remedies: 17.4% of participants | No difference in overall CAM use between cancer patients, cancer survivors, and cancer-free individuals | ||

| Laengler et al. [65] | Cross-sectional study (retrospective) 1063 Germany | Pediatric cancer patients [g] recruited from a cancer registry | CAM use after diagnosis: 34.5% of participants Biologically based practices: 18.2% | Dietary supplement use after diagnosis: 12.2% of participants Megavitamins [h]: 3.1% | |||

| Lapidari et al. [66] | Survey in a cohort study CANTO 5237 France | Women with breast cancer Mean age: 56 years | Chemotherapy: 54.0% of participants Hormone therapy: 80.1% Radiotherapy: 90.6% Surgery (breast): 99.9% | Oral CAM [i] use At or after diagnosis: 23.0% of participants At diagnosis: 11.3% After diagnosis: 11.6% (13.3% of 2829 receiving chemotherapy, 11.8% of 4743 receiving radiotherapy) | Use at or after diagnosis Dietary supplements: 5.4% of participants Herbal supplements: 2.4% Vitamins/minerals: 5.6% | ||

| Lee et al. [67] | Cross-sectional study 1852 South Korea | Cancer survivors recruited from cancer survivor clinics 31% male, 69% female | Chemotherapy: 42.7% of participants Hormone therapy: 27.4% Radiotherapy: 35.6% Surgery: 98.8% | Long-term [j] dietary supplement use: 15.7% of participants (17.1% of 791 receiving chemotherapy, 19.1% of 660 receiving radiotherapy) Multivitamins: 6.9% of participants Omega-3 fatty acids: 3.7% Vitamin C: 5.0% Vitamin D: 3.3% | |||

| Li et al. [52] | Cross-sectional study (serial) NHANES 1999–2014 4023 [e] United States | Cancer survivors 41.8% male, 58.2% female | Botanical dietary supplement use during past 30 days: 15.5 to 23.6% of participants, 18.8% of participants from 1999 through 2014 in total | Higher prevalence of botanical dietary supplement use among patients with cancer in each NHANES cycle | |||

| Loquai et al. [68]; Loquai et al. [69] | Cross-sectional study 1089 Germany | Patients with melanoma recruited from skin cancer centers 46% male, 46% female Mean age: 59 years | Former or current treatment (specified information): 30.8% BRAF-inhibitor: 2.7% Chemotherapy: 2.6% Interferon: 23.8% Ipilimumab: 0.6% Radiotherapy: 3.7% | Current CAM use: 41.0% of participants Biological-based CAM [k]: 25.9% (28.1% of 335 with former or current treatment) | Current CAM supplement use Chinese herbs and teas: 6.4% of participants Dietary supplements: 14.9% Selenium: 6.8% Vitamins: 10.4% | 7.3% of participants (23.9% of 335 with former or current treatment) were at risk of interactions between biological-based CAM and cancer treatment | |

| Luc et al. [70] | Cross-sectional study 5418 [e] United States | Cancer patients registered in the DBBR 40% male, 60% female | Supplement use at enrolment Multivitamins: 50.6% of participants Supplement use during past ten years Beta-carotene: 4.1% of participants Lutein: 2.8% Lycopene: 2.0% Melatonin: 3.0% Selenium: 5.6% Vitamin A: 7.9% Vitamin C: 33.0% Vitamin D: 27.4% Vitamin E: 24.8% | Higher prevalence of supplementation among cancer-free controls | |||

| Mao et al. [71] | Cross-sectional study NHIS 2002 1904 [e] United States | Cancer survivors 38% male, 62% female | CAM use during past 12 months: 39.8% of participants Biological-based CAM [l]: 21% | CAM supplement use during past 12 months Megavitamin: 4.4% of participants Natural products/herbs: 19.4% | Higher prevalence of CAM among cancer survivors (similar to other participants with chronic illnesses) | ||

| Mao et al. [72] | Cross-sectional study NHIS 2007 1471 [e] United States | Cancer survivors 42% male, 59% female | CAM use during past 12 months: 43.3% of participants Biological-based CAM: 26.0% | CAM supplement use during past 12 months Herbs: 23.2% of participants | Higher prevalence of CAM among cancer survivors | ||

| Micke et al. [73] | Cross-sectional study 1013 Germany | Cancer patients receiving radiotherapy recruited from radiotherapy centers 53% male, 47% female Median age: 60 years | Radiotherapy: 100% of participants [m] | CAM use during last 4 weeks before treatment: 59.0% of participants | Supplement use before treatment [n] Selenium: 10% of participants Vitamins: 18% | ||

| Miller et al. [74] | Cross-sectional study CHIS 2001 1844 [e] United States | Cancer patients 33% male, 67% female | Dietary supplement use during past 12 months Herb or botanical: 41.0%/48.9% of 268 cancer only participants/1576 cancer patients with chronic illness Multivitamin: 44.1%/53.0% of 268/1576 Single-vitamin: 54.9%/66.3% of 268/1576 | Higher prevalence of supplement use in adults with cancer or other chronic conditions | |||

| Miller et al. [75] | Survey in a cohort study Penn State Survivor Study 1233 United States | Cancer survivors33% male, 67% female Mean age: 55 years | Regular [o] dietary supplement use during past month: 73.0% of participants Antioxidants [p]: 40% Calcium/vitamin D: 40% Herbal preparations: 21% Multivitamin-multimineral: 62% | ||||

| Pedersen et al. [76] [q] | Survey in a cohort study Nationwide cohort study of Danish women treated for early-stage breast cancer 3343 Denmark | Women with breast cancer treated with surgery Median age: 56 years | Chemotherapy (CEF or CMF) (current): 43.2% of participants Hormone therapy (TAM or TAM + FEM): 62.2% (37.6% current) Radiotherapy: 79.1% (43.8% former) Surgery: 99.8% [m] | CAM use after diagnosis: 40.1% of 3254 participants [r] (49.4% of participants with current chemotherapy; 32.2% of participants with former radiotherapy) | CAM product use after diagnosis Dietary or vitamin supplements: 27.5% of 3254 participants Herbal medicine: 9.6% of 3254 | ||

| Pedersen et al. [77] | Survey in a cohort study Nationwide cohort study of Danish women treated for early-stage breast cancer 2920 Denmark | Women with breast cancer treated with surgery | Treatment received Chemotherapy: 41.9% of participants Radiotherapy: 78.7% Hormone therapy: 64.4% Surgery: 100% [m] | CAM use [s] since participating in first survey: 49.8% of participants | CAM supplement use since participating in first survey Dietary/nutrition supplements: 31.0% of participants Herbal medicine: 11.3% | Higher prevalence of CAM use in believers | |

| Pouchieu et al. [78] | Survey in a cohort study NutriNet-Santé Study 1081 France | Cancer survivors 32% male, 68% female Average age: 60 years | Dietary supplement use after diagnosis: 51.4% of participants Current dietary supplement use: 40.9% Beta-carotene: 4.3% Lutein: 2.9% Lycopene: 0.8% Omega-3 fatty acids: 5.2% Polyphenols: 7.5% Retinol: 5.6% Selenium: 10.6% Vitamin C: 16.2% Vitamin D: 23.2% Vitamin E: 14.7% Zeaxanthin: 1.2% Other herbal supplements: 3.1% | 7 to 8% of 1081 participants (18% of 442 participants with current use of dietary supplements) reported practices with potential adverse effects | |||

| Rosen et al. [79] | Cross-sectional study 1327 United States | Patients with thyroid cancer 11% male, 89% female of 1266 participants [t] Mean age: 47 years | CAM use (except prayer/multivitamins): 74.3% of 1266 participants | CAM supplement use Herbal supplements: 18.5% of 1327 participants Herbal tea: 25.0% Multivitamin/megamultivitamin: 48.4% | |||

| Tank et al. [80] | Cross-sectional study 1217 Germany | Cancer patients recruited from ambulatory cancer care centers 49% male, 51% female Average age: 68 years | Treatment received Oncological medication: 71.9% of participants Radiotherapy (only): 2.4% Surgery (only): 4.6% | Dietary supplement use at study entrance: 47.2% of participants Herbal and botanical supplements: 12.6% of participants Multivitamins: 12.0% Omega-3 fatty acids: 5.7% Selenium: 4.1% Vitamin C: 9.4% Vitamin D: 10.9% Vitamin E: 3.4% | |||

| Velentzis et al. [81] | Survey in a cohort study DietCompLyf study 1560 United Kingdom | Breast cancer patients 100% female | Treatment received Chemotherapy: 46.2 to 51.9% [u] of participants Hormone therapy: 85.3% Radiotherapy: 85.6 to 91.3% [u] Surgery: 94.3 to 100% [u] | Dietary supplement use after diagnosis: 62.8% of participants Multivitamins and minerals: 33.7% Estrogen botanical supplements: 8.4% Vitamin C: 14.6% | Significant increase in the use of supplements, multivitamins and minerals, vitamin C, and estrogen botanical supplements after diagnosis | ||

| Walshe et al. [82] | Survey in a cohort study Cancer Survival Study 1323 Australia | Cancer survivors 58% male, 41% female Median age: 63 years | Treatment received Chemotherapy: 32.8% of participants Hormone therapy: 16.6% Radiotherapy: 28.8% Surgery: 71.5% | Use of biologically based CAM [v] in relation to cancer diagnosis or treatment: 26.4% of participants | Use in relation to cancer diagnosis or treatment Herbal treatments: 8.0% of participants Nutritional supplements or vitamins: 23.1% | Higher prevalence of biologically based CAM use among survivors who received chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or other treatments | |

| Yalcin et al. [83] | Cross-sectional study 1499 Turkey | Cancer patients recruited from an outpatient clinic 28% male, 72% female | Treatment received Chemotherapy: 90% of participants Radiotherapy: 53% Surgery: 70% | CAM use: 95.7% of participants | CAM product use: 4.0% of participants Herbal preparations: 2.8% Vitamins: 0.7% | ||

| Zirpoli et al. [59] | Survey in a cohort study S0221 1249 United States | Patients with breast cancer under treatment 100% female Mean age [w]: 51 years | Treatment: 100% of participants [m] | Supplement use during treatment Multivitamins: 43.2% of 1238 participants Omega-3 fatty acids [x]: 12.6% of 1234 Vitamin C: 11.9% of 1238 Vitamin D: 25.4% of 1239 Vitamin E: 6.4% of 1238 | |||

| Zirpoli et al. [60] | Survey in a cohort study S0221/DELCaP 1225 (1068 completing the second questionnaire) United States | Breast cancer patients under treatment | Treatment received Chemotherapy: 100% of participants [m] | Dietary supplement use during chemotherapy Multivitamin: 44.4% of 1062 participants Omega-3 sources: 13.0% of 1062 Vitamin C: 12.5% of 1060 Vitamin D: 24.8% of 1061 Vitamin E: 6.9% of 1060 | |||

| Zuniga et al. [84] | Survey in a cohort study (serial) CaPSURE 7989 United States | Patients with prostate cancer Average age [a]: 66 years | CAM use after diagnosis: 56% of participants Oral CAM [y] use: 50% | CAM supplement use after diagnosis Vitamins/minerals: 50% of participants Antioxidants: 32% Herbs: 24% Green tea: 11% Multivitamins: 40% Omega-3 fatty acids [z]: 24% Selenium: 8% Vitamin A: 6% Vitamin C: 17% Vitamin D: 21% Vitamin E: 15% | Increase in overall CAM use, use of multivitamins (minor), and use of omega-3 fatty acids Decrease in use of vitamin E, selenium, and lycopene | ||

| PART B | |||||||

| Ambrosone et al. [58] | Cohort study DELCaP (S0221) 1134 United States | Patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy | Chemotherapy: 100% of participants [m] Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, paclitaxel | Supplement use during treatment Antioxidants [aa]: 17.7% of 1132 participants Carotenoid: 1.0% of 1134 Melatonin: 2.1% of 1132 Multivitamins: 43.8% of 1134 Omega-3 fatty acids: 12.6% of 1134 Vitamin A: 2.3% of 1134 Vitamin C: 12.2% of 1134 Vitamin D: 24.6% of 1134 Vitamin E: 6.7% of 1134 | Antioxidants ↑ risk of recurrence (p = 0.06) Antioxidants ↑ mortality (p = 0.14) Vitamin B12 ↑ risk of recurrence * (p < 0.01) Vitamin B12 ↑ mortality * (p < 0.01) Iron (during chemotherapy) ↑ risk of recurrence * (p < 0.01) | ||

| Greenlee et al. [50] | Cohort study LACE 2264 United States | Women with breast cancer with completed treatment Average age: 58 years | Completed treatment: 100% of 2254 participants [m] Chemotherapy: 57.2% Hormone therapy: 80.5% Radiotherapy: 63.0% | Antioxidant-containing supplement [ab] use after diagnosis: 80.8% of participants Beta-carotene: 6% Combination carotenoids: 7% Lycopene: 1% Multivitamins: 70% Selenium: 7% Vitamin C: 40% Vitamin E: 48% | Vitamin C [ac] ↓ risk of recurrence * (p = 0.03) Vitamin E [ac] ↓ risk of recurrence * (p = 0.02) Vitamin E [ac] ↓ all-cause mortality * (p = 0.05) Carotenoids [ac] ↑ breast cancer mortality * (p = 0.01) Carotenoids [ac] ↑ all-cause mortality * (p = 0.01) | ||

| Inoue-Choi et al. [85] | Cohort study IWHS 2118 United States | Cancer survivors 100% female Average age: 79 years | First cancer treatment Chemotherapy: 16.8% of participants Hormone therapy: 22.5% Immunotherapy: 2.3% Radiotherapy: 22.2% Surgery: 93.3% Current treatment: 11.0% | Dietary supplement use during the past 12 months: 84.6% of participants Beta-carotene: 2.3% Multivitamins: 63.8% Selenium: 4.2% Vitamin A: 5.2% Vitamin C: 27.0% Vitamin D: 12.0% Vitamin E: 31.0% | Supplements, multivitamins - mortality Multivitamins ↓ mortality * (high diet quality) (p = 0.02) Multivitamins + other supplements ↑ mortality * (low diet quality) (p = 0.02) Folic acid ↑ mortality * (low diet quality) (p = 0.006) | ||

| Nechuta et al. [57] | Cohort study SBCSS 4877 China | Women with breast cancer | Treatment received within 6 months after diagnosis Chemotherapy: 92.2% of participants Hormone therapy (tamoxifen): 51.7% Radiotherapy: 32.7% | Vitamin supplement use after diagnosis: 36.4% of participants (29.8% of 4497 during chemotherapy; 26.2% of 1597 during radiotherapy) Antioxidants [ad]: 28.3% (22.2% of 4497 during chemotherapy; 20.9% of 1597 during radiotherapy) Multivitamins: 11.0% Vitamin A: 1.7% Vitamin C: 15.3% Vitamin D: 0.4% Vitamin E: 6.1% | Vitamins [ae] ↓ risk of recurrence * (p = 0.06) Vitamins [af] ↓ mortality * (p = 0.05) Antioxidants [ae] ↓ risk of recurrence * (p = 0.02) (participants with no radiotherapy) Antioxidants [af] ↓ mortality * (p = 0.001) (participants with no radiotherapy) Vitamin E [ae] ↓ risk of recurrence * (p = 0.04) Vitamin E [af] ↓ mortality * (p = 0.05) Vitamin C [af] ↓ risk of recurrence * (p = 0.01) Vitamin C [af] ↓ mortality* (p = 0.009) | ||

| Poole et al. [51] | Cohort study ABCPP: SBCSS, LACE, WHEL, NHS 12,019 United States, China | Breast cancer survivors 100% female Mean age [a]: 57 years | Regular [ag] supplement use after treatment: 60.6% of participants Multivitamins: 16.6% (65% of 1999 multivitamin users received chemotherapy; 56% received radiotherapy) Any other single supplement [ai]: 43.9% (60% of 5279 single-supplement users received chemotherapy; 56% received radiotherapy) | Vitamins [ae]–risk of recurrence Vitamins [ae]–mortality Antioxidants [ah] ↓ all-cause mortality * | |||

| Saquib et al. [61] | Cohort study WHEL 2562 United States | Breast cancer survivors 100% female | Prior systemic treatment: 94.3% of 3086 WHEL participants | Dietary supplement use during past 24 h: 85% of participants Antioxidant: 9.8% of 2909 WHEL participants receiving systemic treatment Herbals: 26.0% Herbals (phytoestrogens): 6.9% Multivitamin/mineral: 52.9% Vitamin A: 1.7% Vitamin C: 41.6% Vitamin D: 1.8% Vitamin E: 46.0% | CAM/supplements–risk of recurrence (participants who received systemic treatment) | ||

| Skeie et al. [86] | Cohort study Norwegian Women and Cancer cohort study 2997 Norway | Cancer patients with solid tumors 100% female Mean age [a]: 58 years | Dietary supplement use before diagnosis: 47.1% of participants Occasional use: 10.6% Daily use: 36.5% | Dietary supplements [aj] ↓ mortality * (lung cancer patients) | |||

2.2.1. CAM Supplement Use by Cancer Patients

2.2.2. Possible Adverse Effects of CAM Supplement Use by Cancer Patients

3. The Critical Role of Nrf-2-Keap I in the Interplay between CAM Supplements and Cancer Therapy

3.1. The Nrf-2-Keap I System in ROS Homeostasis and Cancer Drug Resistance

3.1.1. Nrf-2-Keap I as ROS Sensor

3.1.2. Nrf-2 Dual Role in Cancer

3.1.3. Nrf-2 in Cancer Cell Resistance

3.2. Nrf-2 Activation by Cancer Drugs and the Role of CAMS

3.2.1. Main Targets of Cancer Drugs and ROS Production as a Side-Effect

- How do CAMSs, and especially antioxidants, interact with the Nrf-2 pathway during cancer therapy?

- Do CAMSs induce Nrf-2 activation followed by an adaptive stress response of healthy cells or do CAMSs even help the tumor cells acquire resistance?

- What lessons did we learn from clinical studies with antioxidants as adjuvants in cancer therapy?

- In consequence, how do CAMSs interact with anticancer drugs and radiotherapy and influence their success in cancer therapy?

3.2.2. Anthracyclines

3.2.3. Platin-Based Cytostatics

3.2.4. Taxanes

3.2.5. Alkylating Anticancer Drugs

3.2.6. Radiation Therapy

3.3. Recent Clinical Trials with Combined Cancer and Adjuvant Antioxidant Therapy

4. Conclusions

5. Recommendations and Outlook

- Dose-dependent pharmacokinetic studies with combined CAMS along with radiation and/or chemotherapy.

- An establishment of stable biomarkers for drug resistance

- Large-scale studies with cancer patients taking self-administered supplements

- Healthcare professionals need to strengthen communication with cancer patients on the use of CAMSs, especially during anticancer therapy

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Fact Sheet Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- GCO; IARC; WHO. Fact Sheet All Cancers 2020. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/39-All-cancers-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cancer (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Cancer Research UK. Cancer Survival Statistics. Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/survival (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- IARC. International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership (ICBP) Cancer Survival in High-Income Countries (SURVMARK-2). Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/survival/survmark/ (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Global trends in cancer incidence and mortality. In World Cancer Report. Cancer Research for Cancer Prevention; Wild, C.P., Weiderpass, E., Stewart, B.W., Eds.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IARC. Trends in Age-Standardized Incidence, Mortality Rates (25–99 Years) and 5-Year Net Survival (15–99 years), Colorectal, United Kingdom, Both Sexes. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/survival/survmark/visualizations/viz2/?cancer_site=%22Colorectal%22&country=%22United+Kingdom%22&agegroup=%22All%22&gender=%22All%22&interval=%221%22&survival_year=%225%22&measures=%5B%22Incidence+%28ASR%29%22%2C%22Mortality+%28ASR%29%22%2C%22Net+Survival%22%5D (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Bayat Mokhtari, R.; Homayouni, T.S.; Baluch, N.; Morgatskaya, E.; Kumar, S.; Das, B.; Yeger, H. Combination therapy in combating cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 38022–38043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tang, S.M.; Deng, X.T.; Zhou, J.; Li, Q.P.; Ge, X.X.; Miao, L. Pharmacological basis and new insights of quercetin action in respect to its anti-cancer effects. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 121, 109604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. Side Effects of Cancer Treatment. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/survivors/patients/side-effects-of-treatment.htm (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- NCI. Side Effects of Cancer Treatment. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Yale Medicine. Side Effects of Cancer Treatment. Available online: https://www.yalemedicine.org/conditions/side-effects-cancer-treatment (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Yang, H.; Villani, R.M.; Wang, H.; Simpson, M.J.; Roberts, M.S.; Tang, M.; Liang, X. The role of cellular reactive oxygen species in cancer chemotherapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Montane, X.; Kowalczyk, O.; Reig-Vano, B.; Bajek, A.; Roszkowski, K.; Tomczyk, R.; Pawliszak, W.; Giamberini, M.; Mocek-Plociniak, A.; Tylkowski, B. Current Perspectives of the Applications of Polyphenols and Flavonoids in Cancer Therapy. Molecules 2020, 25, 3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, K.I.; Mead, M.N. Vitamin C in alternative cancer treatment: Historical background. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2003, 2, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttger, F.; Valles-Marti, A.; Cahn, L.; Jimenez, C.R. High-dose intravenous vitamin C, a promising multi-targeting agent in the treatment of cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Shan, H.; Yang, W.; Zhang, J.; Dai, H.; Ye, Z. Vitamin E for the Prevention of Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy: A meta-Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 684550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.A.; Sulaiman, A.A.; Balch, C.; Chauhan, H.; Alhadidi, Q.M.; Tiwari, A.K. Natural Polyphenols in Cancer Chemoresistance. Nutr. Cancer 2016, 68, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, U.; Gorlach, S.; Owczarek, K.; Hrabec, E.; Szewczyk, K. Synergistic interactions between anticancer chemotherapeutics and phenolic compounds and anticancer synergy between polyphenols. Postepy Hig. Med. Dosw. (Online) 2014, 68, 528–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedzwiecki, A.; Roomi, M.W.; Kalinovsky, T.; Rath, M. Anticancer Efficacy of Polyphenols and Their Combinations. Nutrients 2016, 8, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yasueda, A.; Urushima, H.; Ito, T. Efficacy and Interaction of Antioxidant Supplements as Adjuvant Therapy in Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2016, 15, 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ernst, E.; Cassileth, B.R. The prevalence of complementary/alternative medicine in cancer: A systematic review. Cancer 1998, 83, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horneber, M.; Bueschel, G.; Dennert, G.; Less, D.; Ritter, E.; Zwahlen, M. How many cancer patients use complementary and alternative medicine: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2012, 11, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Velicer, C.M.; Ulrich, C.M. Vitamin and mineral supplement use among US adults after cancer diagnosis: A systematic review. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCI. Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/cam (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- De Almeida Andrade, F.; Schlechta Portella, C.F. Research methods in complementary and alternative medicine: An integrative review. J. Integr. Med. 2018, 16, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, F. Discovering the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Oncology Patients: A Systematic Literature Review. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 6619243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLay, J.S.; Stewart, D.; George, J.; Rore, C.; Heys, S.D. Complementary and alternative medicines use by Scottish women with breast cancer. What, why and the potential for drug interactions? Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 68, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wode, K.; Henriksson, R.; Sharp, L.; Stoltenberg, A.; Hök Nordberg, J. Cancer patients’ use of complementary and alternative medicine in Sweden: A cross-sectional study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balneaves, L.G.; Wong, M.E.; Porcino, A.J.; Truant, T.L.O.; Thorne, S.E.; Wong, S.T. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) information and support needs of Chinese-speaking cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 4151–4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navo, M.A.; Phan, J.; Vaughan, C.; Palmer, J.L.; Michaud, L.; Jones, K.L.; Bodurka, D.C.; Basen-Engquist, K.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Kavanagh, J.J.; et al. An assessment of the utilization of complementary and alternative medication in women with gynecologic or breast malignancies. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pihlak, R.; Liivand, R.; Trelin, O.; Neissar, H.; Peterson, I.; Kivistik, S.; Lilo, K.; Jaal, J. Complementary medicine use among cancer patients receiving radiotherapy and chemotherapy: Methods, sources of information and the need for counselling. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.) 2014, 23, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortune Business Insights. Market Research Report. Over The Counter (OTC) Drugs Market Size, Share & COVID-19 Impact Analysis, By Product Type, By Distribution Channel, and Regional Forecast, 2021–2028; FBI105433; Fortune Business Insights: Pune, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Informa Markets. Supplement Business Report 2022; Informa Markets: Mumbai, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Asher, G.N.; Corbett, A.H.; Hawke, R.L. Common Herbal Dietary Supplement-Drug Interactions. Am. Fam. Physician 2017, 96, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.H.; Chin, Y.W. Multifaceted Factors Causing Conflicting Outcomes in Herb-Drug Interactions. Pharmaceutics 2020, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koziolek, M.; Alcaro, S.; Augustijns, P.; Basit, A.W.; Grimm, M.; Hens, B.; Hoad, C.L.; Jedamzik, P.; Madla, C.M.; Maliepaard, M.; et al. The mechanisms of pharmacokinetic food-drug interactions—A perspective from the UNGAP group. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 134, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohn, E.S.; Kern, H.J.; Saltzman, E.; Mitmesser, S.H.; McKay, D.L. Evidence of Drug-Nutrient Interactions with Chronic Use of Commonly Prescribed Medications: An Update. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mouly, S.; Lloret-Linares, C.; Sellier, P.O.; Sene, D.; Bergmann, J.F. Is the clinical relevance of drug-food and drug-herb interactions limited to grapefruit juice and Saint-John’s Wort? Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 118, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, G.L.; Collins, M.; Lu, X.; Lodi, A.; DiGiovanni, J.; Tiziani, S. Predicting and Quantifying Antagonistic Effects of Natural Compounds Given with Chemotherapeutic Agents: Applications for High-Throughput Screening. Cancers 2020, 12, 3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faw, C.; Ballentine, R.; Ballentine, L.; vanEys, J. Unproved cancer remedies. A survey of use in pediatric outpatients. JAMA 1977, 238, 1536–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molassiotis, A.; Fernández-Ortega, P.; Pud, D.; Ozden, G.; Scott, J.A.; Panteli, V.; Margulies, A.; Browall, M.; Magri, M.; Selvekerova, S.; et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients: A European survey. Ann. Oncol. 2005, 16, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, H.S.; Olatunde, F.; Zick, S.M. Trends in complementary/alternative medicine use by breast cancer survivors: Comparing survey data from 1998 and 2005. BMC Womens Health 2007, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, V.; Goyal, A.; Hsu, C.C.; Jacobson, J.S.; Rodriguez, R.D.; Siegel, A.B. Dietary supplement use among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2015, 14, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, C.; Rachow, T.; Ernst, T.; Hochhaus, A.; Zomorodbakhsch, B.; Foller, S.; Rengsberger, M.; Hartmann, M.; Huebner, J. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) supplements in cancer outpatients: Analyses of usage and of interaction risks with cancer treatment. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 148, 1123–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, P.; Butler, M.; Coughlan, B.; Murray, M.; Boland, N.; Hanan, T.; Murphy, H.; Forrester, P.; Brien, M.O.; Sullivan, N.O. Using a mixed methods research design to investigate complementary alternative medicine (CAM) use among women with breast cancer in Ireland. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2013, 17, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, A.Y.; Cai, X.; Thoene, K.; Obi, N.; Jaskulski, S.; Behrens, S.; Flesch-Janys, D.; Chang-Claude, J. Antioxidant supplementation and breast cancer prognosis in postmenopausal women undergoing chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenlee, H.; Kwan, M.L.; Kushi, L.H.; Song, J.; Castillo, A.; Weltzien, E.; Quesenberry, C.P., Jr.; Caan, B.J. Antioxidant supplement use after breast cancer diagnosis and mortality in the Life After Cancer Epidemiology (LACE) cohort. Cancer 2012, 118, 2048–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poole, E.M.; Shu, X.; Caan, B.J.; Flatt, S.W.; Holmes, M.D.; Lu, W.; Kwan, M.L.; Nechuta, S.J.; Pierce, J.P.; Chen, W.Y. Postdiagnosis supplement use and breast cancer prognosis in the after Breast Cancer Pooling Project. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013, 139, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, C.; Hansen, R.A.; Chou, C.; Calderón, A.I.; Qian, J. Trends in botanical dietary supplement use among US adults by cancer status: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 to 2014. Cancer 2018, 124, 1207–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenlee, H.; Kwan, M.L.; Ergas, I.J.; Sherman, K.J.; Krathwohl, S.E.; Bonnell, C.; Lee, M.M.; Kushi, L.H. Complementary and alternative therapy use before and after breast cancer diagnosis: The Pathways Study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2009, 117, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenlee, H.; Kwan, M.L.; Ergas, I.J.; Strizich, G.; Roh, J.M.; Wilson, A.T.; Lee, M.; Sherman, K.J.; Ambrosone, C.B.; Hershman, D.L.; et al. Changes in vitamin and mineral supplement use after breast cancer diagnosis in the Pathways Study: A prospective cohort study. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, Z.; Gu, K.; Zheng, Y.; Zheng, W.; Lu, W.; Shu, X.O. The use of complementary and alternative medicine among Chinese women with breast cancer. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2008, 14, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Bao, P.; Cai, H.; Hong, Z.; Ding, D.; Jackson, J.; Shu, X.O.; Dai, Q. Associations of dietary intake and supplement use with post-therapy cognitive recovery in breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 171, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nechuta, S.; Lu, W.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Gu, K.; Cai, H.; Zheng, W.; Shu, X.O. Vitamin supplement use during breast cancer treatment and survival: A prospective cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2011, 20, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ambrosone, C.B.; Zirpoli, G.R.; Hutson, A.D.; McCann, W.E.; McCann, S.E.; Barlow, W.E.; Kelly, K.M.; Cannioto, R.; Sucheston-Campbell, L.E.; Hershman, D.L.; et al. Dietary Supplement Use During Chemotherapy and Survival Outcomes of Patients With Breast Cancer Enrolled in a Cooperative Group Clinical Trial (SWOG S0221). J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zirpoli, G.R.; Brennan, P.M.; Hong, C.C.; McCann, S.E.; Ciupak, G.; Davis, W.; Unger, J.M.; Budd, G.T.; Hershman, D.L.; Moore, H.C.; et al. Supplement use during an intergroup clinical trial for breast cancer (S0221). Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013, 137, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zirpoli, G.R.; McCann, S.E.; Sucheston-Campbell, L.E.; Hershman, D.L.; Ciupak, G.; Davis, W.; Unger, J.M.; Moore, H.C.F.; Stewart, J.A.; Isaacs, C.; et al. Supplement Use and Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy in a Cooperative Group Trial (S0221): The DELCaP Study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saquib, J.; Parker, B.A.; Natarajan, L.; Madlensky, L.; Saquib, N.; Patterson, R.E.; Newman, V.A.; Pierce, J.P. Prognosis following the use of complementary and alternative medicine in women diagnosed with breast cancer. Complement. Ther. Med. 2012, 20, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conway, R.E.; Rigler, F.V.; Croker, H.A.; Lally, P.J.; Beeken, R.J.; Fisher, A. Dietary supplement use by individuals living with and beyond breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer: A cross-sectional survey. Cancer 2022, 128, 1331–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, G.M.; Hershman, D.L.; Falci, L.; Shi, Z.; Tsai, W.Y.; Greenlee, H. Complementary and alternative medicine use among US cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2016, 10, 850–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristoffersen, A.E.; Stub, T.; Broderstad, A.R.; Hansen, A.H. Use of traditional and complementary medicine among Norwegian cancer patients in the seventh survey of the Tromsø study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laengler, A.; Spix, C.; Seifert, G.; Gottschling, S.; Graf, N.; Kaatsch, P. Complementary and alternative treatment methods in children with cancer: A population-based retrospective survey on the prevalence of use in Germany. Eur. J. Cancer 2008, 44, 2233–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapidari, P.; Djehal, N.; Havas, J.; Gbenou, A.; Martin, E.; Charles, C.; Dauchy, S.; Pistilli, B.; Cadeau, C.; Bertaut, A.; et al. Determinants of use of oral complementary-alternative medicine among women with early breast cancer: A focus on cancer-related fatigue. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 190, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.R.; Song, Y.M.; Jeon, K.H.; Cho, I.Y. The Association between the Use of Dietary Supplement and Psychological Status of Cancer Survivors in Korea: A Cross-Sectional Study. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2021, 42, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loquai, C.; Dechent, D.; Garzarolli, M.; Kaatz, M.; Kaehler, K.C.; Kurschat, P.; Meiss, F.; Micke, O.; Muecke, R.; Muenstedt, K.; et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine: A multicenter cross-sectional study in 1089 melanoma patients. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 71, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loquai, C.; Schmidtmann, I.; Garzarolli, M.; Kaatz, M.; Kähler, K.C.; Kurschat, P.; Meiss, F.; Micke, O.; Muecke, R.; Muenstedt, K.; et al. Interactions from complementary and alternative medicine in patients with melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2017, 27, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luc, L.; Baumgart, C.; Weiss, E.; Georger, L.; Ambrosone, C.B.; Zirpoli, G.; McCann, S.E. Dietary supplement use among participants of a databank and biorepository at a comprehensive cancer centre. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 916–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mao, J.J.; Farrar, J.T.; Xie, S.X.; Bowman, M.A.; Armstrong, K. Use of complementary and alternative medicine and prayer among a national sample of cancer survivors compared to other populations without cancer. Complement. Ther. Med. 2007, 15, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.J.; Palmer, C.S.; Healy, K.E.; Desai, K.; Amsterdam, J. Complementary and alternative medicine use among cancer survivors: A population-based study. J. Cancer Surviv. 2011, 5, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Micke, O.; Bruns, F.; Glatzel, M.; Schonekaes, K.; Micke, P.; Mucke, R.; Buntzel, J. Predictive factors for the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in radiation oncology. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2009, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.F.; Bellizzi, K.M.; Sufian, M.; Ambs, A.H.; Goldstein, M.S.; Ballard-Barbash, R. Dietary supplement use in individuals living with cancer and other chronic conditions: A population-based study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008, 108, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, P.E.; Vasey, J.J.; Short, P.F.; Hartman, T.J. Dietary supplement use in adult cancer survivors. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2009, 36, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pedersen, C.G.; Christensen, S.; Jensen, A.B.; Zachariae, R. Prevalence, socio-demographic and clinical predictors of post-diagnostic utilisation of different types of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in a nationwide cohort of Danish women treated for primary breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 3172–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, C.G.; Christensen, S.; Jensen, A.B.; Zachariae, R. In God and CAM we trust. Religious faith and use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in a nationwide cohort of women treated for early breast cancer. J. Relig. Health 2013, 52, 991–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouchieu, C.; Fassier, P.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Zelek, L.; Bachmann, P.; Touillaud, M.; Bairati, I.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Cohen, P.; et al. Dietary supplement use among cancer survivors of the NutriNet-Santé cohort study. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 1319–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosen, J.E.; Gardiner, P.; Saper, R.B.; Filippelli, A.C.; White, L.F.; Pearce, E.N.; Gupta-Lawrence, R.L.; Lee, S.L. Complementary and alternative medicine use among patients with thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2013, 23, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tank, M.; Franz, K.; Cereda, E.; Norman, K. Dietary supplement use in ambulatory cancer patients: A survey on prevalence, motivation and attitudes. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 147, 1917–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velentzis, L.S.; Keshtgar, M.R.; Woodside, J.V.; Leathem, A.J.; Titcomb, A.; Perkins, K.A.; Mazurowska, M.; Anderson, V.; Wardell, K.; Cantwell, M.M. Significant changes in dietary intake and supplement use after breast cancer diagnosis in a UK multicentre study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 128, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walshe, R.; James, E.L.; MacDonald-Wicks, L.; Boyes, A.W.; Zucca, A.; Girgis, A.; Lecathelinais, C. Socio-demographic and medical correlates of the use of biologically based complementary and alternative medicines amongst recent Australian cancer survivors. Prev. Med. 2012, 54, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yalcin, S.; Hurmuz, P.; McQuinn, L.; Naing, A. Prevalence of Complementary Medicine Use in Patients With Cancer: A Turkish Comprehensive Cancer Center Experience. J. Glob. Oncol. 2017, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuniga, K.B.; Zhao, S.J.; Kenfield, S.A.; Cedars, B.; Cowan, J.E.; Van Blarigan, E.L.; Broering, J.M.; Carroll, P.R.; Chan, J.M. Trends in Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use among Patients with Prostate Cancer. J. Urol. 2019, 202, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue-Choi, M.; Greenlee, H.; Oppeneer, S.J.; Robien, K. The association between postdiagnosis dietary supplement use and total mortality differs by diet quality among older female cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2014, 23, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Skeie, G.; Braaten, T.; Hjartåker, A.; Brustad, M.; Lund, E. Cod liver oil, other dietary supplements and survival among cancer patients with solid tumours. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 125, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, S.; Zachariae, R.; Jensen, A.B.; Vaeth, M.; Moller, S.; Ravnsbaek, J.; von der Maase, H. Prevalence and risk of depressive symptoms 3-4 months post-surgery in a nationwide cohort study of Danish women treated for early stage breast-cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2009, 113, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sweet, E.; Dowd, F.; Zhou, M.; Standish, L.J.; Andersen, M.R. The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Supplements of Potential Concern during Breast Cancer Chemotherapy. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 2016, 4382687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weeks, L.; Balneaves, L.G.; Paterson, C.; Verhoef, M. Decision-making about complementary and alternative medicine by cancer patients: Integrative literature review. Open Med. 2014, 8, e54–e66. [Google Scholar]

- Zachariae, R. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Patients with Cancer: A Challenge in the Oncologist-Patient Relationship. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1177–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, M.; Sierpina, V. The use of dietary supplements in oncology. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2014, 16, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsanad, S.M.; Howard, R.L.; Williamson, E.M. An assessment of the impact of herb-drug combinations used by cancer patients. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hyodo, I.; Amano, N.; Eguchi, K.; Narabayashi, M.; Imanishi, J.; Hirai, M.; Nakano, T.; Takashima, S. Nationwide survey on complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients in Japan. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 2645–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Umsatz mit Nahrungsergänzungsmitteln in Deutschland nach Vertriebslinien im Jahr 2022 (in Millionen Euro) (Erhebung durch NielsenIQ). Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1308546/umfrage/umsatz-mit-nahrungsergaenzungsmitteln-nach-vertriebslinien/ (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Davis, E.L.; Oh, B.; Butow, P.N.; Mullan, B.A.; Clarke, S. Cancer patient disclosure and patient-doctor communication of complementary and alternative medicine use: A systematic review. Oncologist 2012, 17, 1475–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenkel, M.; Cohen, L. Effective communication about the use of complementary and integrative medicine in cancer care. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2014, 20, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- American Cancer Society. Are Dietary Supplements Safe? Available online: https://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/treatment-types/complementary-and-integrative-medicine/dietary-supplements/safety.html (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Greenlee, H.; Neugut, A.I.; Falci, L.; Hillyer, G.C.; Buono, D.; Mandelblatt, J.S.; Roh, J.M.; Ergas, I.J.; Kwan, M.L.; Lee, M.; et al. Association Between Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use and Breast Cancer Chemotherapy Initiation: The Breast Cancer Quality of Care (BQUAL) Study. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1170–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.R.; Sweet, E.; Lowe, K.A.; Standish, L.J.; Drescher, C.W.; Goff, B.A. Dangerous combinations: Ingestible CAM supplement use during chemotherapy in patients with ovarian cancer. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2013, 19, 714–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Firkins, R.; Eisfeld, H.; Keinki, C.; Buentzel, J.; Hochhaus, A.; Schmidt, T.; Huebner, J. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients in routine care and the risk of interactions. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 144, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, C.; Rachow, T.; Ernst, T.; Hochhaus, A.; Zomorodbakhsch, B.; Foller, S.; Rengsberger, M.; Hartmann, M.; Huebner, J. Interactions in cancer treatment considering cancer therapy, concomitant medications, food, herbal medicine and other supplements. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 148, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, F.; Bairati, I.; Fortin, A.; Gelinas, M.; Nabid, A.; Brochet, F.; Tetu, B. Interaction between antioxidant vitamin supplementation and cigarette smoking during radiation therapy in relation to long-term effects on recurrence and mortality: A randomized trial among head and neck cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 122, 1679–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, A.I.; Câtoi, C. Comparative Oncology; The Publishing House of the Romanian Academy: Bucharest, Romania, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Emami Nejad, A.; Najafgholian, S.; Rostami, A.; Sistani, A.; Shojaeifar, S.; Esparvarinha, M.; Nedaeinia, R.; Haghjooy Javanmard, S.; Taherian, M.; Ahmadlou, M.; et al. The role of hypoxia in the tumor microenvironment and development of cancer stem cell: A novel approach to developing treatment. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeaz, C.; Totis, C.; Bisio, A. Radiation Resistance: A Matter of Transcription Factors. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 662840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, A.; Kang, M.I.; Okawa, H.; Ohtsuji, M.; Zenke, Y.; Chiba, T.; Igarashi, K.; Yamamoto, M. Oxidative stress sensor Keap1 functions as an adaptor for Cul3-based E3 ligase to regulate proteasomal degradation of Nrf2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 7130–7139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kobayashi, M.; Yamamoto, M. Nrf2-Keap1 regulation of cellular defense mechanisms against electrophiles and reactive oxygen species. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 2006, 46, 113–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Lu, H.; Bai, Y. Nrf2 in cancers: A double-edged sword. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 2252–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuadrado, A.; Manda, G.; Hassan, A.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Barbas, C.; Daiber, A.; Ghezzi, P.; Leon, R.; Lopez, M.G.; Oliva, B.; et al. Transcription Factor NRF2 as a Therapeutic Target for Chronic Diseases: A Systems Medicine Approach. Pharmacol. Rev. 2018, 70, 348–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rojo de la Vega, M.; Chapman, E.; Zhang, D.D. NRF2 and the Hallmarks of Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Zhou, X.; Qiu, J. Emerging role of NRF2 in ROS-mediated tumor chemoresistance. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 131, 110676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solis, L.M.; Behrens, C.; Dong, W.; Suraokar, M.; Ozburn, N.C.; Moran, C.A.; Corvalan, A.H.; Biswal, S.; Swisher, S.G.; Bekele, B.N.; et al. Nrf2 and Keap1 abnormalities in non-small cell lung carcinoma and association with clinicopathologic features. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 3743–3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sporn, M.B.; Liby, K.T. NRF2 and cancer: The good, the bad and the importance of context. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ohkoshi, A.; Suzuki, T.; Ono, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Yamamoto, M. Roles of Keap1-Nrf2 system in upper aerodigestive tract carcinogenesis. Cancer Prev. Res. 2013, 6, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Milkovic, L.; Zarkovic, N.; Saso, L. Controversy about pharmacological modulation of Nrf2 for cancer therapy. Redox Biol. 2017, 12, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, W.Y.; Cui, Y.K.; Hong, Y.X.; Li, Y.D.; Wu, Y.; Li, G.; Li, G.R.; Wang, Y. Doxorubicin cardiomyopathy is ameliorated by acacetin via Sirt1-mediated activation of AMPK/Nrf2 signal molecules. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 12141–12153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansanen, E.; Kuosmanen, S.M.; Leinonen, H.; Levonen, A.L. The Keap1-Nrf2 pathway: Mechanisms of activation and dysregulation in cancer. Redox Biol. 2013, 1, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucker, S.N.; Fink, E.E.; Bagati, A.; Mannava, S.; Bianchi-Smiraglia, A.; Bogner, P.N.; Wawrzyniak, J.A.; Foley, C.; Leonova, K.I.; Grimm, M.J.; et al. Nrf2 amplifies oxidative stress via induction of Klf9. Mol. Cell 2014, 53, 916–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chhunchha, B.; Kubo, E.; Singh, D.P. Sulforaphane-Induced Klf9/Prdx6 Axis Acts as a Molecular Switch to Control Redox Signaling and Determines Fate of Cells. Cells 2019, 8, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Holohan, C.; Van Schaeybroeck, S.; Longley, D.B.; Johnston, P.G. Cancer drug resistance: An evolving paradigm. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 714–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhou, L.; Xie, N.; Nice, E.C.; Zhang, H.; Huang, C.; Lei, Y. Cancer drug resistance: Redox resetting renders a way. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 42740–42761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, L.; Du, Y.; Gan, F.; Li, Y.; Yao, Y. Antioxidative Stress: Inhibiting Reactive Oxygen Species Production as a Cause of Radioresistance and Chemoresistance. Oxid Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 6620306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.Y.; Lu, M.C.; You, Q.D. Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 (Nrf2) Inhibition: An Emerging Strategy in Cancer Therapy. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 3840–3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Hong, X.; Zhao, F.; Ci, X.; Zhang, S. Targeting Nrf2 may reverse the drug resistance in ovarian cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Wang, J.Q.; Assaraf, Y.G.; Ren, L.; Gupta, P.; Wei, L.; Ashby, C.R., Jr.; Yang, D.H.; Chen, Z.S. Modulating ROS to overcome multidrug resistance in cancer. Drug Resist. Updat. 2018, 41, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Kim, H.S.; Seo, Y.R. Understanding of ROS-Inducing Strategy in Anticancer Therapy. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 5381692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, S.; Hushmandi, K.; Zabolian, A.; Saleki, H.; Torabi, S.M.R.; Ranjbar, A.; SeyedSaleh, S.; Sharifzadeh, S.O.; Khan, H.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; et al. Elucidating Role of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Cisplatin Chemotherapy: A Focus on Molecular Pathways and Possible Therapeutic Strategies. Molecules 2021, 26, 2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panieri, E.; Santoro, M.M. ROS homeostasis and metabolism: A dangerous liason in cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robledinos-Anton, N.; Fernandez-Gines, R.; Manda, G.; Cuadrado, A. Activators and Inhibitors of NRF2: A Review of Their Potential for Clinical Development. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 9372182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sun, J.; Wei, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Xu, H. A systematic analysis of FDA-approved anticancer drugs. BMC Syst. Biol. 2017, 11, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, J.; Loos, B.; Marais, E.; Engelbrecht, A.M. Mitochondrial catastrophe during doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: A review of the protective role of melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 2014, 57, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiles, J.L.; Huertas, J.R.; Battino, M.; Mataix, J.; Ramírez-Tortosa, M.C. Antioxidant nutrients and adriamycin toxicity. Toxicology 2002, 180, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallustio, B.C.; Boddy, A.V. Is there scope for better individualisation of anthracycline cancer chemotherapy? Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarmohammadi, F.; Rezaee, R.; Karimi, G. Natural compounds against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: A review on the involvement of Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 1163–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Danelisen, I.; Singal, P.K. Early changes in myocardial antioxidant enzymes in rats treated with adriamycin. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2002, 232, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroshow, J.H.; Locker, G.Y.; Myers, C.E. Enzymatic defenses of the mouse heart against reactive oxygen metabolites: Alterations produced by doxorubicin. J. Clin. Investig. 1980, 65, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nordgren, K.K.; Wallace, K.B. Keap1 redox-dependent regulation of doxorubicin-induced oxidative stress response in cardiac myoblasts. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2014, 274, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordgren, K.K.S.; Wallace, K.B. Disruption of the Keap1/Nrf2-Antioxidant Response System After Chronic Doxorubicin Exposure In Vivo. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2020, 20, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dalen, E.C.; Caron, H.N.; Dickinson, H.O.; Kremer, L.C. Cardioprotective interventions for cancer patients receiving anthracyclines. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 2016, CD003917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granados-Principal, S.; Quiles, J.L.; Ramirez-Tortosa, C.L.; Sanchez-Rovira, P.; Ramirez-Tortosa, M.C. New advances in molecular mechanisms and the prevention of adriamycin toxicity by antioxidant nutrients. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 1425–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalcanti, I.D.L.; Soares, J.C.S.; Medeiros, S.M.d.F.R.d.S.; Cavalcanti, I.M.F.; Lira Nogueira, M.C.d.B. Can antioxidant vitamins avoid the cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin in treating breast cancer? PharmaNutrition 2021, 16, 100259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Montero, J.; Chichiarelli, S.; Eufemi, M.; Altieri, F.; Saso, L.; Rodrigo, R. Ascorbate as a Bioactive Compound in Cancer Therapy: The Old Classic Strikes Back. Molecules 2022, 27, 3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoppe, C.; Freuding, M.; Buntzel, J.; Munstedt, K.; Hubner, J. Clinical efficacy and safety of oral and intravenous vitamin C use in patients with malignant diseases. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 147, 3025–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhail, N.; Bilal, N.; Khan, H.Y.; Hasan, S.; Sharma, S.; Khan, F.; Mansoor, T.; Banu, N. Effect of vitamins C and E on antioxidant status of breast-cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2012, 37, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisia, I.; Kitts, D.D. Tocopherol isoforms (alpha-, gamma-, and delta-) show distinct capacities to control Nrf-2 and NfkappaB signaling pathways that modulate inflammatory response in Caco-2 intestinal cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 404, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vineetha, R.C.; Binu, P.; Arathi, P.; Nair, R.H. L-ascorbic acid and alpha-tocopherol attenuate arsenic trioxide-induced toxicity in H9c2 cardiomyocytes by the activation of Nrf2 and Bcl2 transcription factors. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2018, 28, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedhiafi, T.; Inchakalody, V.P.; Fernandes, Q.; Mestiri, S.; Billa, N.; Uddin, S.; Merhi, M.; Dermime, S. The potential role of vitamin C in empowering cancer immunotherapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 146, 112553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.L.; Zhao, B.; Sun, S.L.; Yu, S.F.; Wang, Y.M.; Ji, R.; Yang, Z.T.; Ma, L.; Yao, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. High-dose vitamin C alleviates pancreatic injury via the NRF2/NQO1/HO-1 pathway in a rat model of severe acute pancreatitis. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Hortal, M.D.; Varela-Lopez, A.; Romero-Marquez, J.M.; Rivas-Garcia, L.; Speranza, L.; Battino, M.; Quiles, J.L. Role of flavonoids against adriamycin toxicity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 146, 111820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zhang, J.; Ni, T.; Lin, N.; Meng, L.; Gao, F.; Luo, H.; Liu, X.; Chi, J.; Guo, H. Yellow Wine Polyphenolic Compounds prevents Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity through activation of the Nrf2 signalling pathway. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 6034–6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barakat, B.M.; Ahmed, H.I.; Bahr, H.I.; Elbahaie, A.M. Protective Effect of Boswellic Acids against Doxorubicin-Induced Hepatotoxicity: Impact on Nrf2/HO-1 Defense Pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 8296451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bai, Z.; Wang, Z. Genistein protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity through Nrf-2/HO-1 signaling in mice model. Environ. Toxicol. 2019, 34, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calcabrini, C.; Maffei, F.; Turrini, E.; Fimognari, C. Sulforaphane Potentiates Anticancer Effects of Doxorubicin and Cisplatin and Mitigates Their Toxic Effects. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, C.; Awasthi, S.; Sharma, R.; Benes, H.; Hauer-Jensen, M.; Boerma, M.; Singh, S.P. Sulforaphane potentiates anticancer effects of doxorubicin and attenuates its cardiotoxicity in a breast cancer model. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutabian, H.; Ghahramani-Asl, R.; Mortezazadeh, T.; Laripour, R.; Narmani, A.; Zamani, H.; Ataei, G.; Bagheri, H.; Farhood, B.; Sathyapalan, T.; et al. The cardioprotective effects of nano-curcumin against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: A systematic review. Biofactors 2022, 48, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, L. In Vitro and In Vivo Cardioprotective Effects of Curcumin against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity: A Systematic Review. J. Oncol. 2022, 2022, 7277562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.; Shaikh, J.; Naba, Y.S.; Doke, K.; Ahmed, K.; Yusufi, M. Curcumin: Reclaiming the lost ground against cancer resistance. Cancer Drug Resist. 2021, 4, 298–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, B.L.; Norhaizan, M.E. Curcumin Combination Chemotherapy: The Implication and Efficacy in Cancer. Molecules 2019, 24, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lecumberri, E.; Dupertuis, Y.M.; Miralbell, R.; Pichard, C. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) as adjuvant in cancer therapy. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 32, 894–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sahin, K.; Tuzcu, M.; Gencoglu, H.; Dogukan, A.; Timurkan, M.; Sahin, N.; Aslan, A.; Kucuk, O. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate activates Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Life Sci. 2010, 87, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, M.H.; Adhami, V.M.; Lee, J.S.; Mukhtar, H. Constitutive overexpression of Nrf2-dependent heme oxygenase-1 in A549 cells contributes to resistance to apoptosis induced by epigallocatechin 3-gallate. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 33761–33772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, W.; Nie, S.; Xie, M.; Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, H. A major green tea component, (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate, ameliorates doxorubicin-mediated cardiotoxicity in cardiomyocytes of neonatal rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 8977–8982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.W.; Zhu, X.H.; Zhao, T.; Zhong, J.; Gao, H.C.; Luo, X.L.; Huang, W.R. EGCG Enhanced the Anti-tumor Effect of Doxorubicine in Bladder Cancer via NF-kappaB/MDM2/p53 Pathway. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 606123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, S.; Tchounwou, P.B. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: Molecular mechanisms of action. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 740, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, Y.M.; Kim, H.K.; Shim, W.; Anwar, M.A.; Kwon, J.W.; Kwon, H.K.; Kim, H.J.; Jeong, H.; Kim, H.M.; Hwang, D.; et al. Mechanism of Cisplatin-Induced Cytotoxicity Is Correlated to Impaired Metabolism Due to Mitochondrial ROS Generation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marullo, R.; Werner, E.; Degtyareva, N.; Moore, B.; Altavilla, G.; Ramalingam, S.S.; Doetsch, P.W. Cisplatin induces a mitochondrial-ROS response that contributes to cytotoxicity depending on mitochondrial redox status and bioenergetic functions. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Volarevic, V.; Djokovic, B.; Jankovic, M.G.; Harrell, C.R.; Fellabaum, C.; Djonov, V.; Arsenijevic, N. Molecular mechanisms of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity: A balance on the knife edge between renoprotection and tumor toxicity. J. Biomed. Sci. 2019, 26, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, B.; Gu, X.; Huang, X. The Role of the Reactive Oxygen Species Scavenger Agent, Astaxanthin, in the Protection of Cisplatin-Treated Patients Against Hearing Loss. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2019, 13, 4291–4303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Yin, X.; Shi, G.; Li, H.; Hu, Z.; Liang, X. Emodin enhances cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity in human bladder cancer cells through ROS elevation and MRP1 downregulation. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.J.; Li, Y.; Luo, L.; Wang, H.; Chi, Z.; Xin, A.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Tang, X. Oxaliplatin activates the Keap1/Nrf2 antioxidant system conferring protection against the cytotoxicity of anticancer drugs. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 70, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.J.; Hayes, J.D.; Wolf, C.R. Generation of a stable antioxidant response element-driven reporter gene cell line and its use to show redox-dependent activation of nrf2 by cancer chemotherapeutic agents. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 10983–10994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Furqan, M.; Abu-Hejleh, T.; Stephens, L.M.; Hartwig, S.M.; Mott, S.L.; Pulliam, C.F.; Petronek, M.; Henrich, J.B.; Fath, M.A.; Houtman, J.C.; et al. Pharmacological ascorbate improves the response to platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer. Redox Biol. 2022, 53, 102318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, H.; Li, R.; Chen, D.; Hu, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, C.; Wen, Z. Protective Effects of Vitamin E on Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 77, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retzlaff, D.; Dorfler, J.; Kutschan, S.; Freuding, M.; Buntzel, J.; Hubner, J. The Vitamin E Isoform alpha-Tocopherol is Not Effective as a Complementary Treatment in Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review. Nutr. Cancer 2022, 74, 2313–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankovic, J.S.K.; Selakovic, D.; Mihailovic, V.; Rosic, G. Antioxidant Supplementation in the Treatment of Neurotoxicity Induced by Platinum-Based Chemotherapeutics-A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, J.; Molina-Jijon, E.; Medina-Campos, O.N.; Rodriguez-Munoz, R.; Reyes, J.L.; Loredo, M.L.; Barrera-Oviedo, D.; Pinzon, E.; Rodriguez-Rangel, D.S.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. Curcumin prevents cisplatin-induced decrease in the tight and adherens junctions: Relation to oxidative stress. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howells, L.M.; Iwuji, C.O.O.; Irving, G.R.B.; Barber, S.; Walter, H.; Sidat, Z.; Griffin-Teall, N.; Singh, R.; Foreman, N.; Patel, S.R.; et al. Curcumin Combined with FOLFOX Chemotherapy Is Safe and Tolerable in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer in a Randomized Phase IIa Trial. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 1133–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-Beltran, C.E.; Calderon-Oliver, M.; Tapia, E.; Medina-Campos, O.N.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, D.J.; Martinez-Martinez, C.M.; Ortiz-Vega, K.M.; Franco, M.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. Sulforaphane protects against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 2010, 192, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karvan, S.; Sadeghi, A.; Farrokhi, P.; Nekouee, A.; Sharifi, M.; Moghaddas, A. Melatonin in the prevention of cisplatin-induced acute nephrotoxicity: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 17, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, I.; Lehmann, H.C. Pathomechanisms of Paclitaxel-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. Toxics 2021, 9, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, L.; Ilari, A.; Fazi, F.; Assaraf, Y.G.; Colotti, G. Taxanes in cancer treatment: Activity, chemoresistance and its overcoming. Drug Resist. Updat. 2021, 54, 100742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, J.; Batteux, F.; Nicco, C.; Chereau, C.; Laurent, A.; Guillevin, L.; Weill, B.; Goldwasser, F. Accumulation of hydrogen peroxide is an early and crucial step for paclitaxel-induced cancer cell death both in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 119, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggett, N.A.; Griffiths, L.A.; McKenna, O.E.; de Santis, V.; Yongsanguanchai, N.; Mokori, E.B.; Flatters, S.J. Oxidative stress in the development, maintenance and resolution of paclitaxel-induced painful neuropathy. Neuroscience 2016, 333, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, H.S.; Oh, J.M.; Jin, D.H.; Yang, K.H.; Moon, E.Y. Paclitaxel induces vascular endothelial growth factor expression through reactive oxygen species production. Pharmacology 2008, 81, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiba, M.A.; Ismail, S.S.; Sabry, M.; Bayoumy, W.A.E.; Kamal, K.A. The use of vitamin E in preventing taxane-induced peripheral neuropathy. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2021, 88, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyriou, A.A.; Chroni, E.; Koutras, A.; Iconomou, G.; Papapetropoulos, S.; Polychronopoulos, P.; Kalofonos, H.P. Preventing paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy: A phase II trial of vitamin E supplementation. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2006, 32, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moignet, A.; Hasanali, Z.; Zambello, R.; Pavan, L.; Bareau, B.; Tournilhac, O.; Roussel, M.; Fest, T.; Awwad, A.; Baab, K.; et al. Cyclophosphamide as a first-line therapy in LGL leukemia. Leukemia 2014, 28, 1134–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukourakis, G.V.; Kouloulias, V.; Zacharias, G.; Papadimitriou, C.; Pantelakos, P.; Maravelis, G.; Fotineas, A.; Beli, I.; Chaldeopoulos, D.; Kouvaris, J. Temozolomide with radiation therapy in high grade brain gliomas: Pharmaceuticals considerations and efficacy; a review article. Molecules 2009, 14, 1561–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chien, C.H.; Hsueh, W.T.; Chuang, J.Y.; Chang, K.Y. Dissecting the mechanism of temozolomide resistance and its association with the regulatory roles of intracellular reactive oxygen species in glioblastoma. J. Biomed. Sci. 2021, 28, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos-Sandoval, J.A.; Gomez-Garcia, M.C.; Santos-Jimenez, J.L.; Mates, J.M.; Alonso, F.J.; Marquez, J. Antioxidant responses related to temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma. Neurochem. Int. 2021, 149, 105136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aladaileh, S.H.; Abukhalil, M.H.; Saghir, S.A.M.; Hanieh, H.; Alfwuaires, M.A.; Almaiman, A.A.; Bin-Jumah, M.; Mahmoud, A.M. Galangin Activates Nrf2 Signaling and Attenuates Oxidative Damage, Inflammation, and Apoptosis in a Rat Model of Cyclophosphamide-Induced Hepatotoxicity. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bael, T.E.; Peterson, B.L.; Gollob, J.A. Phase II trial of arsenic trioxide and ascorbic acid with temozolomide in patients with metastatic melanoma with or without central nervous system metastases. Melanoma Res. 2008, 18, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Ye, W.; Shao, Q.; Zhang, M.; Liang, J. Nrf2 is a potential therapeutic target in radioresistance in human cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2013, 88, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Long, F.; Lin, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, T. Dietary Phytochemicals Targeting Nrf2 to Enhance the Radiosensitivity of Cancer. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 7848811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enkhbat, T.; Nishi, M.; Yoshikawa, K.; Jun, H.; Tokunaga, T.; Takasu, C.; Kashihara, H.; Ishikawa, D.; Tominaga, M.; Shimada, M. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate Enhances Radiation Sensitivity in Colorectal Cancer Cells Through Nrf2 Activation and Autophagy. Anticancer Res. 2018, 38, 6247–6252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.S.; Wilkes, J.G.; Schroeder, S.R.; Buettner, G.R.; Wagner, B.A.; Du, J.; Gibson-Corley, K.; O’Leary, B.R.; Spitz, D.R.; Buatti, J.M.; et al. Pharmacologic Ascorbate Reduces Radiation-Induced Normal Tissue Toxicity and Enhances Tumor Radiosensitization in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 6838–6851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bairati, I.; Meyer, F.; Jobin, E.; Gelinas, M.; Fortin, A.; Nabid, A.; Brochet, F.; Tetu, B. Antioxidant vitamins supplementation and mortality: A randomized trial in head and neck cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 119, 2221–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayed, R.; El Wakeel, L.; Saad, A.S.; Kelany, M.; El-Hamamsy, M. Pentoxifylline and vitamin E reduce the severity of radiotherapy-induced oral mucositis and dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients: A randomized, controlled study. Med. Oncol. 2019, 37, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharman, S.; Maragathavalli, G.; Shanmugasundaram, K.; Sampath, R.K. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Efficacy of Curcumin/Turmeric for the Prevention and Amelioration of Radiotherapy/Radiochemotherapy Induced Oral Mucositis in Head and Neck Cancer Patients. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2021, 22, 1671–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tang, G.; Wei, Z. Prophylactic and Therapeutic Effects of Curcumin on Treatment-Induced Oral Mucositis in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutr. Cancer 2021, 73, 740–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zheng, M.; Meng, X.; Kong, L.; Zhang, S.; He, D.; et al. Efficacy of Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate in Preventing Dermatitis in Patients With Breast Cancer Receiving Postoperative Radiotherapy: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2022, 158, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Xie, P.; Li, X.; Zhu, W.; Sun, X.; Sun, X.; Chen, X.; Xing, L.; Yu, J. A prospective phase II trial of EGCG in treatment of acute radiation-induced esophagitis for stage III lung cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 2015, 114, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Park, S.; Koyanagi, A.; Yang, J.W.; Jacob, L.; Yon, D.K.; Lee, S.W.; Kim, M.S.; Il Shin, J.; Smith, L. Effects of exogenous melatonin supplementation on health outcomes: An umbrella review of meta-analyses based on randomized controlled trials. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 176, 106052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chapman, J.; Levine, M.; Polireddy, K.; Drisko, J.; Chen, Q. High-dose parenteral ascorbate enhanced chemosensitivity of ovarian cancer and reduced toxicity of chemotherapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 222ra218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.K.; Bhutani, M.; Guleria, R.; Bal, S.; Mohan, A.; Mohanti, B.K.; Sharma, A.; Pathak, R.; Bhardwaj, N.K.; Prasad, K.N.; et al. Chemotherapy alone vs. chemotherapy plus high dose multiple antioxidants in patients with advanced non small cell lung cancer. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2005, 24, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferslew, K.E.; Acuff, R.V.; Daigneault, E.A.; Woolley, T.W.; Stanton, P.E., Jr. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of the RRR and all racemic stereoisomers of alpha-tocopherol in humans after single oral administration. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1993, 33, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreyev, H.J.N.; Matthews, J.; Adams, C.; Gothard, L.; Lucy, C.; Tovey, H.; Boyle, S.; Anbalagan, S.; Musallam, A.; Yarnold, J.; et al. Randomised single centre double-blind placebo controlled phase II trial of Tocovid SupraBio in combination with pentoxifylline in patients suffering long-term gastrointestinal adverse effects of radiotherapy for pelvic cancer: The PPALM study. Radiother. Oncol. 2022, 168, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vareed, S.K.; Kakarala, M.; Ruffin, M.T.; Crowell, J.A.; Normolle, D.P.; Djuric, Z.; Brenner, D.E. Pharmacokinetics of curcumin conjugate metabolites in healthy human subjects. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2008, 17, 1411–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Flory, S.; Sus, N.; Haas, K.; Jehle, S.; Kienhofer, E.; Waehler, R.; Adler, G.; Venturelli, S.; Frank, J. Increasing Post-Digestive Solubility of Curcumin Is the Most Successful Strategy to Improve its Oral Bioavailability: A Randomized Cross-Over Trial in Healthy Adults and In Vitro Bioaccessibility Experiments. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2021, 65, e2100613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, X.; Fan, H.; Liu, Y. Curcumin upregulates transcription factor Nrf2, HO-1 expression and protects rat brains against focal ischemia. Brain Res. 2009, 1282, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, H.H.; Hakim, I.A.; Vining, D.R.; Crowell, J.A.; Ranger-Moore, J.; Chew, W.M.; Celaya, C.A.; Rodney, S.R.; Hara, Y.; Alberts, D.S. Effects of dosing condition on the oral bioavailability of green tea catechins after single-dose administration of Polyphenon E in healthy individuals. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 4627–4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, X.; Li, J.; Liu, K.; Wang, F.; Liu, K.; Liu, Q.; Yang, C.; et al. Anti-cancer activities of tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate in breast cancer patients under radiotherapy. Curr. Mol. Med. 2012, 12, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shekarri, Q.; Dekker, M. A Physiological-Based Model for Simulating the Bioavailability and Kinetics of Sulforaphane from Broccoli Products. Foods 2021, 10, 2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozanovski, V.J.; Houben, P.; Hinz, U.; Hackert, T.; Herr, I.; Schemmer, P. Pilot study evaluating broccoli sprouts in advanced pancreatic cancer (POUDER trial)—Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014, 15, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harpsøe, N.G.; Andersen, L.P.; Gögenur, I.; Rosenberg, J. Clinical pharmacokinetics of melatonin: A systematic review. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 71, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, A.; Marruecos, J.; Rubio, J.; Farre, N.; Gomez-Millan, J.; Morera, R.; Planas, I.; Lanzuela, M.; Vazquez-Masedo, M.G.; Cascallar, L.; et al. Randomized placebo-controlled phase II trial of high-dose melatonin mucoadhesive oral gel for the prevention and treatment of oral mucositis in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing radiation therapy concurrent with systemic treatment. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 23, 1801–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tascioglu Aliyev, A.; Panieri, E.; Stepanic, V.; Gurer-Orhan, H.; Saso, L. Involvement of NRF2 in Breast Cancer and Possible Therapeutical Role of Polyphenols and Melatonin. Molecules 2021, 26, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, A.C.S.; Zortea, M.; Souza, A.; Santos, V.; Biazus, J.V.; Torres, I.L.S.; Fregni, F.; Caumo, W. Clinical impact of melatonin on breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy; effects on cognition, sleep and depressive symptoms: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]