The Effects of Maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp) on Cellular Oxidative Stress: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Criteria of Selection

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategies

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Risk of Publication Bias between Studies

2.5. Methodological Quality and Risk of Bias of Individual Studies

2.6. Statistical Analysis and Synthesis of Results in Studies

3. Results

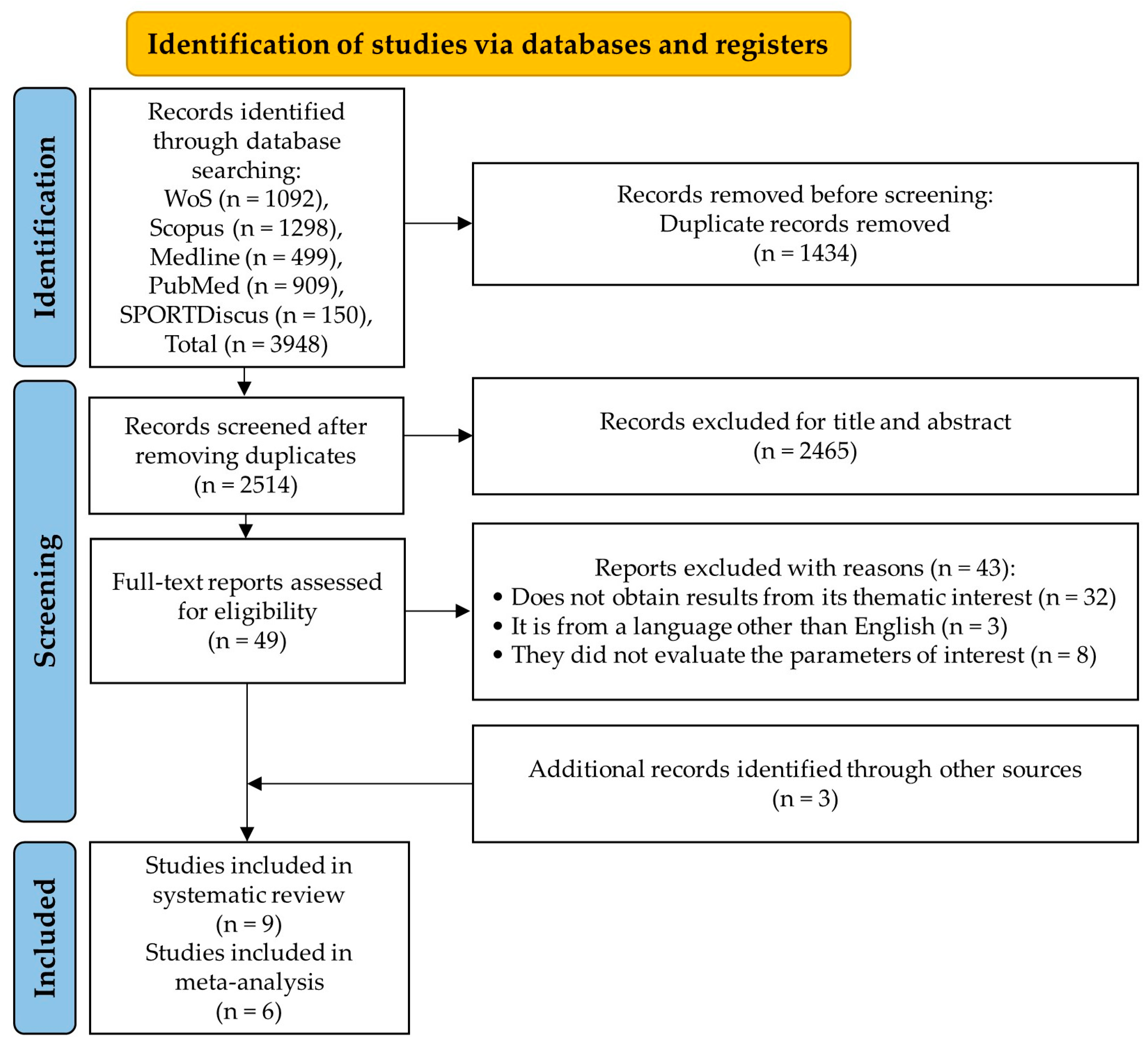

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Assessment of Methodological Quality of Individual Studies

3.3. Meta-Analysis

3.4. Publication Bias

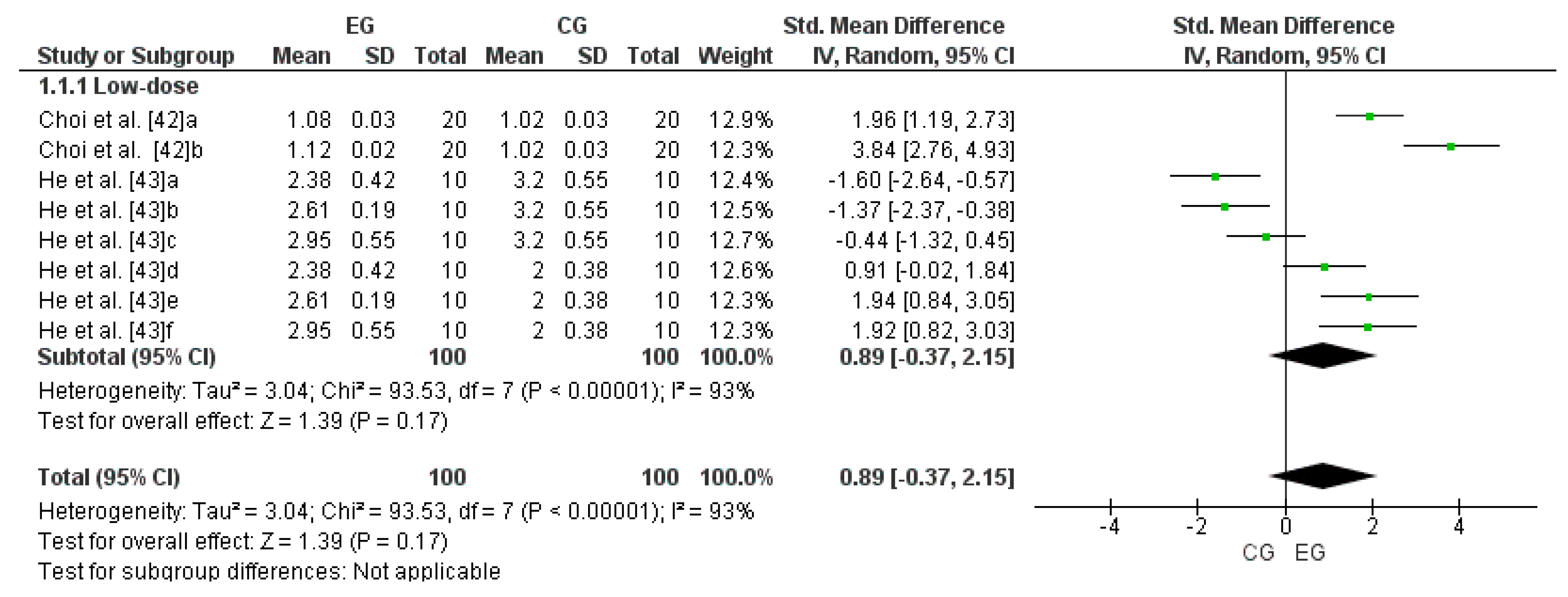

3.5. Effect of LmW on Reduced Glutathione

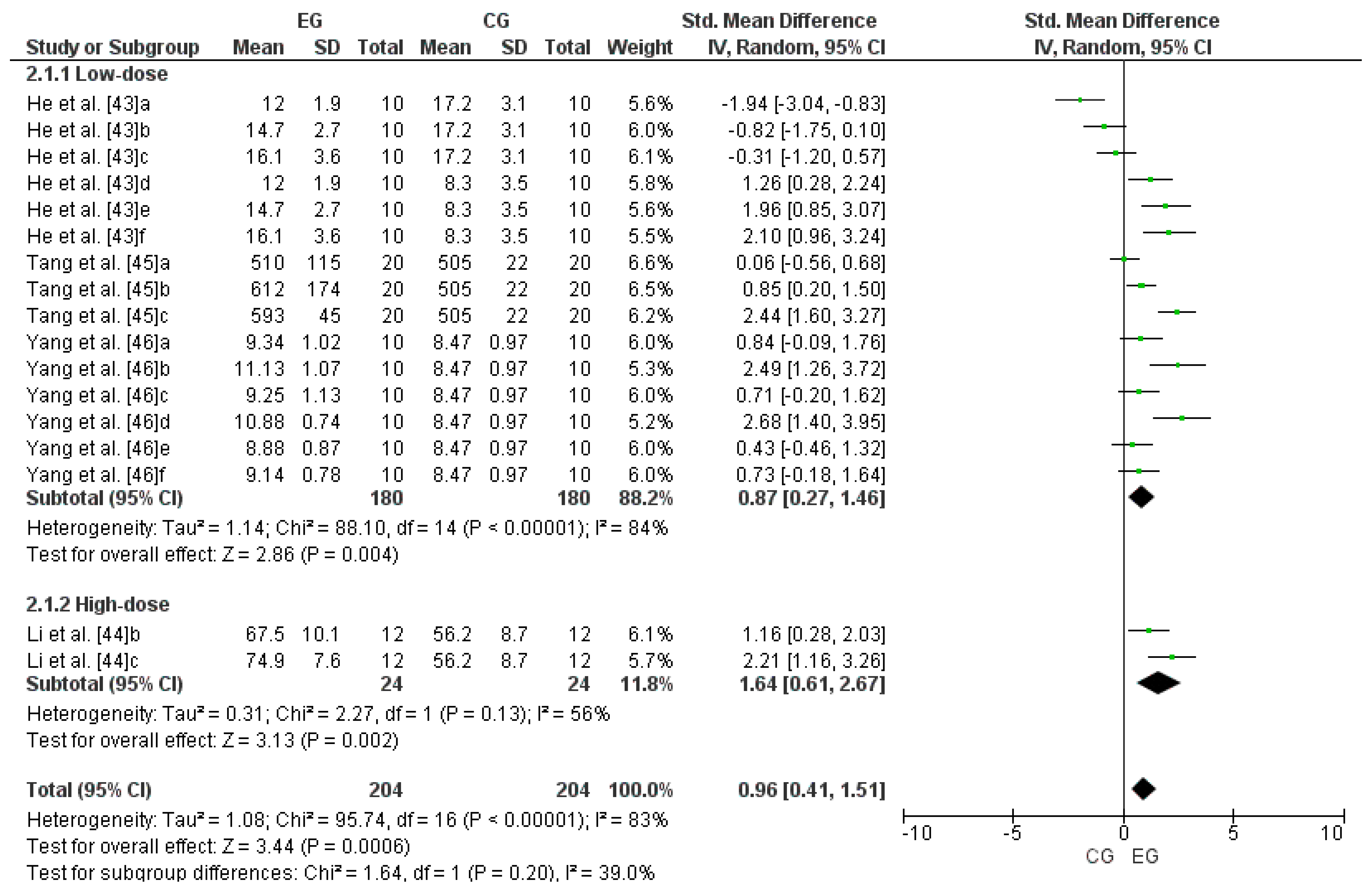

3.6. Effect of LmW on Glutathione Peroxidase

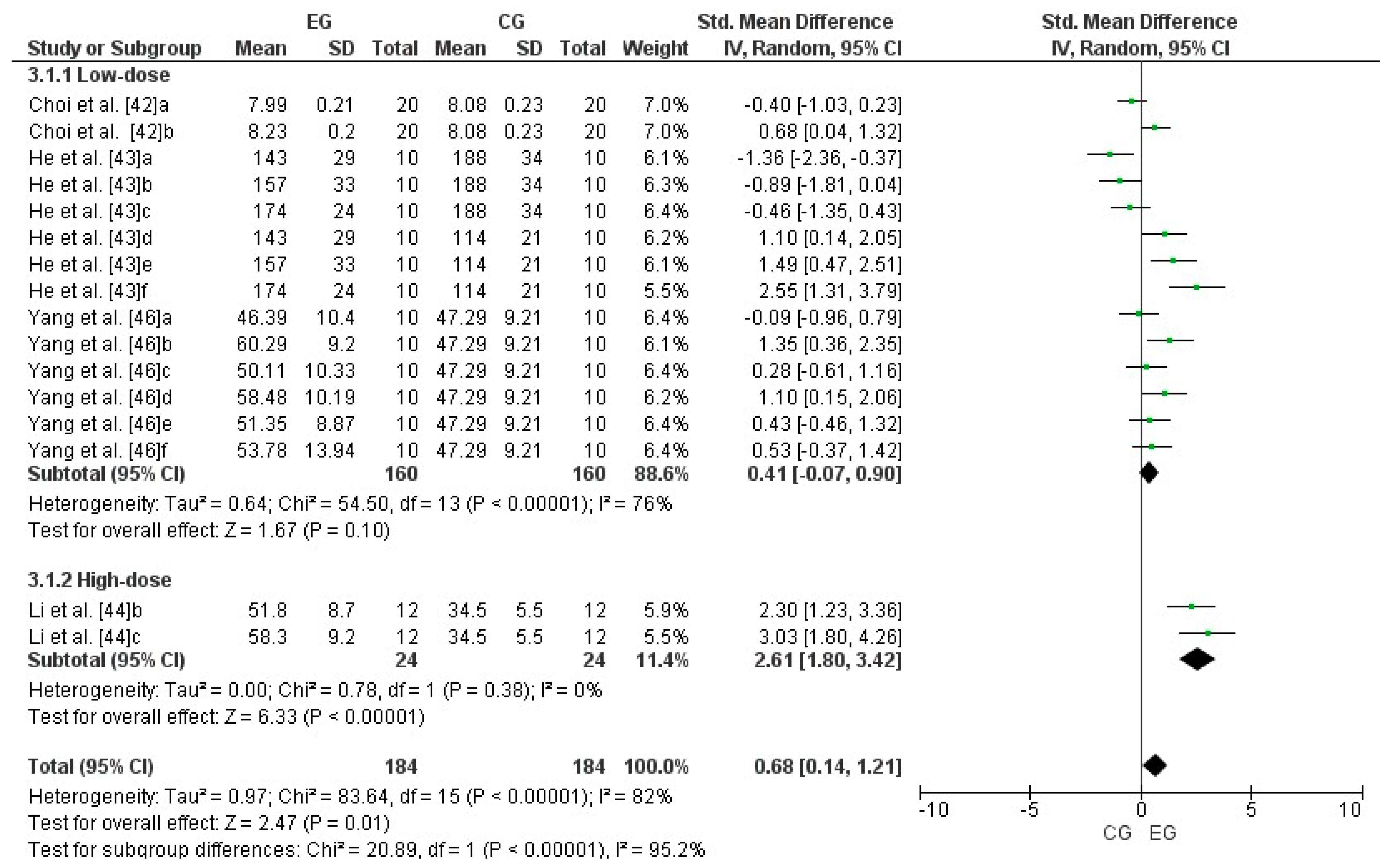

3.7. Effect of LmW on Superoxide Dismutase

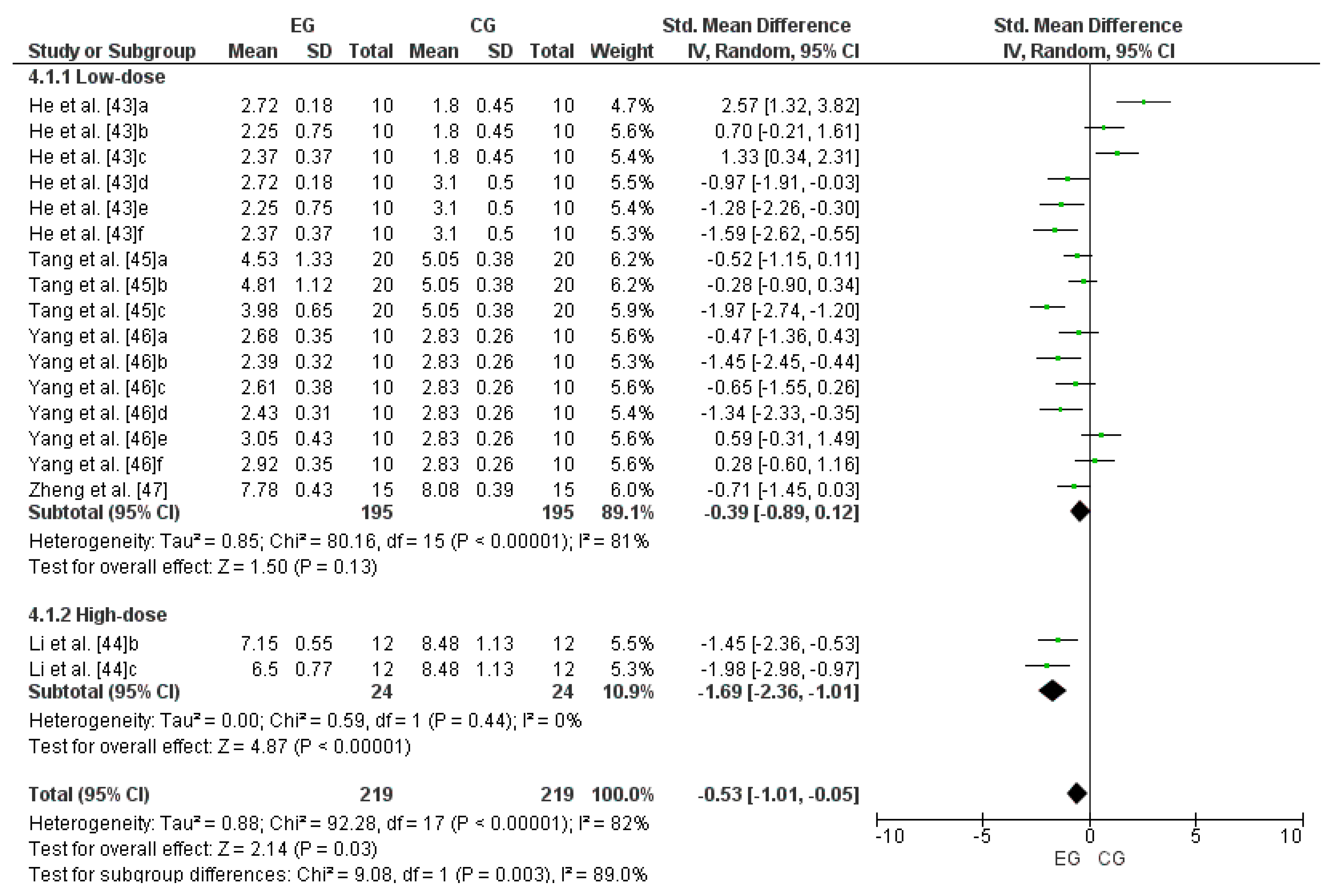

3.8. Effect of LmW on Malondialdehyde

4. Discussion

4.1. LmW Supplementation on Reduced Glutathione

4.2. LmW Supplementation on Glutathione Peroxidase

4.3. LmW Supplementation on Superoxide Dismutase

4.4. LmW Supplementation on Malondialdehyde

4.5. Extraction and Synthesis of Bioactive Compounds of LmW

4.6. Dose and Timing of LmW Supplementation for Oxidative Stress Control

4.7. Polysaccharide Content in LmW Roots and Leaves

4.8. Transcription of Genes Coding for Antioxidant Enzymes

4.9. Antioxidant Capacity of LmW and Its Comparison with Other Foods in the Region

4.10. Limitations

5. Conclusions

6. Future Lines of Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martemucci, G.; Costagliola, C.; Mariano, M.; D’andrea, L.; Napolitano, P.; D’Alessandro, A.G. Free Radical Properties, Source and Targets, Antioxidant Consumption and Health. Oxygen 2022, 2, 48–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phaniendra, A.; Jestadi, D.B.; Periyasamy, L. Free Radicals: Properties, Sources, Targets, and Their Implication in Various Diseases. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2015, 30, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussa, R.O. On the Binding of Adrenocorticotropin to Proteins during Isolation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1969, 188, 331–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruteanu, L.L.; Bailey, D.S.; Grădinaru, A.C.; Jäntschi, L. The Biochemistry and Effectiveness of Antioxidants in Food, Fruits, and Marine Algae. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, P.; Janmeda, P.; Docea, A.O.; Yeskaliyeva, B.; Abdull Razis, A.F.; Modu, B.; Calina, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Oxidative Stress, Free Radicals and Antioxidants: Potential Crosstalk in the Pathophysiology of Human Diseases. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1158198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Li, T.; Wu, X.; Nice, E.C.; Huang, C.; Zhang, Y. Oxidative Stress and Diabetes: Antioxidative Strategies. Front. Med. 2020, 14, 583–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.-J.; Yuan, S.; Zi, H.; Gu, J.-M.; Fang, C.; Zeng, X.-T. Oxidative Stress Links Aging-Associated Cardiovascular Diseases and Prostatic Diseases. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 5896136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, A.J.P.O.; de Almeida Rezende, M.S.; Dantas, S.H.; de Lima Silva, S.; de Oliveira, J.C.P.L.; de Lourdes Assunção Araújo de Azevedo, F.; Alves, R.M.F.R.; de Menezes, G.M.S.; dos Santos, P.F.; Gonçalves, T.A.F.; et al. Unveiling the Role of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress on Age-Related Cardiovascular Diseases. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 1954398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Park, Y.S. The Emerging Roles of Antioxidant Enzymes by Dietary Phytochemicals in Vascular Diseases. Life 2021, 11, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panth, N.; Paudel, K.R.; Parajuli, K. Reactive Oxygen Species: A Key Hallmark of Cardiovascular Disease. Adv. Med. 2016, 2016, 9152732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taverne, Y.J.H.J.; Bogers, A.J.J.C.; Duncker, D.J.; Merkus, D. Reactive Oxygen Species and the Cardiovascular System. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2013, 2013, 862423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wattanapitayakul, S.K.; Bauer, J.A. Oxidative Pathways in Cardiovascular Disease: Roles, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Implications. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 89, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orhan, C.; Gencoglu, H.; Tuzcu, M.; Sahin, N.; Ojalvo, S.P.; Sylla, S.; Komorowski, J.R.; Sahin, K. Maca Could Improve Endurance Capacity Possibly by Increasing Mitochondrial Biogenesis Pathways and Antioxidant Response in Exercised Rats. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Zhu, Z.Y.; Pan, L.C.; Sun, H.; Song, Q.Y.; Zhang, Y. Structure Analysis and Anti-Fatigue Activity of a Polysaccharide from Lepidium meyenii Walp. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 33, 2480–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sifuentes-Penagos, G.; León-Vásquez, S.; Paucar-Menacho, L.M. Estudio de La Maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp.), Cultivo Andino Con Propiedades Terapéuticas [Study of Maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp.), Andean Crop with Therapeutic Properties]. Sci. Agropecu. 2015, 6, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beharry, S.; Heinrich, M. Is the Hype around the Reproductive Health Claims of Maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp.) Justified? J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 211, 126–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, G.F.; Villaorduña, L.; Gasco, M.; Rubio, J.; Gonzales, C. Maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp), Una Revisión Sobre Sus Propiedades Biológicas [Maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp), a Review of Its Biological Properties. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud Publica 2014, 31, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Peng, Z.; Lai, W.; Shao, Y.; Gao, Q.; He, M.; Zhou, W.; Guo, L.; Kang, J.; Jin, X.; et al. The Efficient Synthesis and Anti-Fatigue Activity Evaluation of Macamides: The Unique Bioactive Compounds in Maca. Molecules 2023, 28, 3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamou, B.; Taiwe, G.S.; Hamadou, A.; Abene; Houlray, J.; Atour, M.M.; Tan, P.V. Antioxidant and Antifatigue Properties of the Aqueous Extract of Moringa Oleifera in Rats Subjected to Forced Swimming Endurance Test. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 3517824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Hao, L.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, Z.; Yang, Y. Isolation, Purification and Antioxidant Activity of Polysaccharides from the Leaves of Maca (Lepidium meyenii). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107, 2611–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, S.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, B. Extraction, Purification and Antioxidant Activities of the Polysaccharides from Maca (Lepidium meyenii). Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 111, 584–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, S.A.; Wadley, G.D.; Keske, M.A.; Parker, L. Effect of Mitochondrial-Targeted Antioxidants on Glycaemic Control, Cardiovascular Health, and Oxidative Stress in Humans: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2022, 24, 1047–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkmaz, S. Antioxidants in Maca (Lepidium meyenii) as a Supplement in Nutrition. In Antioxidants in Foods and Its Applications; Shalaby, E., Azzam, G.M., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2018; pp. 137–154. ISBN 978-1-78923-379-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hybertson, B.M.; Gao, B.; Bose, S.K.; McCord, J.M. Oxidative Stress in Health and Disease: The Therapeutic Potential of Nrf2 Activation. Mol. Asp. Med. 2011, 32, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, W.; Zhang, J.; Yu, S.; Yue, N.; Ye, D.; Zhu, Y.; Tao, R.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, A.; et al. Antioxidative and Energy Metabolism-Improving Effects of Maca Polysaccharide on Cyclophosphamide-Induced Hhepatotoxicity Mice via Metabolomic Analysis and Keap1-Nrf2 Pathway. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, J.; Feng, Y.; He, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, H. Correlations between Antioxidant Activity and Alkaloids and Phenols of Maca (Lepidium meyenii). J. Food Qual. 2017, 2017, 3185945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, G.F.; Gasco, M.; Lozada-Requena, I. Role of Maca (Lepidium meyenii) Consumption on Serum Interleukin-6 Levels and Health Status in Populations Living in the Peruvian Central Andes over 4000 m of Altitude. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2013, 68, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, L.; Ao, M.; Jin, W. Effect of Ethanol Extract of Lepidium meyenii Walp. on Osteoporosis in Ovariectomized Rat. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 105, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Du, S.; Tian, M.; Xu, W.; Tian, Y.; Li, T.; Fu, Y.; Wu, S.; Li, C.; Jin, N. Lepidium meyenii Walp Exhibits Anti-Inflammatory Activity against ConA-Induced Acute Hepatitis. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018, 2018, 8982756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Xu, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L. Effects of Astaxanthin Supplementation on Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2020, 90, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbaninejad, P.; Sheikhhossein, F.; Djafari, F.; Tijani, A.J.; Mohammadpour, S.; Shab-Bidar, S. Effects of Melatonin Supplementation on Oxidative Stress: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2020, 41, 20200030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Milla, P.; Peñalver, R.; Nieto, G. A Review of the Functional Characteristics and Applications of Aristotelia chilensis (Maqui Berry), in the Food Industry. Foods 2024, 13, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.-L.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Yang, Z.-H.; Huang, D.; Weng, H.; Zeng, X.-T. Methodological Quality (Risk of Bias) Assessment Tools for Primary and Secondary Medical Studies: What Are They and Which Is Better? Mil. Med. Res. 2020, 7, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.-F.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Cao, M.-J.; Zhang, L.-J.; Sun, L.-C.; Su, W.-J.; Liu, G.-M. Hypoxia Tolerance and Fatigue Relief Produced by Lepidium meyenii and Its Water-Soluble Polysaccharide in Mice. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2016, 22, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in Meta-Analysis Detected by a Simple, Graphical Test, Graphical Test. BMJ 1998, 316, 629–634. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges, L.V. Distribution Theory for Glass’s Estimator of Effect Size and Related Estimators. J. Educ. Stat. 1981, 6, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring Inconsistency in Meta-Analyses. Br. Med. J. 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Xu, W.; Wang, N.; Jiang, W.; Cheng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yao, W.; Hu, B.; Du, P.; Qian, H. Anti-Fatigue Effect of Lepidium meyenii Walp. (Maca) on Preventing Mitochondria-Mediated Muscle Damage and Oxidative Stress In Vivo and Vitro. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 3132–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, R.; Hua, H.; Qian, H.; Du, P. Deciphering the Potential Role of Maca Compounds Prescription Influencing Gut Microbiota in the Management of Exercise-Induced Fatigue by Integrative Genomic Analysis. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1004174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.H.; Kang, J.I.; Cho, J.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, T.S.; Yeo, I.H.; Chun, H.S. Supplementation of Standardized Lipid-Soluble Extract from Maca (Lepidium meyenii) Increases Swimming Endurance Capacity in Rats. J. Funct. Foods 2012, 4, 568–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.-C.; Li, R.-W.; Zhu, H.-Y. The Effects of Polysaccharides from Maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp.) on Exhaustive Exercise-Induced Oxidative Damage in Rats. Biomed. Res. 2017, 28, 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Duan, Z.; Zhu, S.; Fan, L. The Composition Analysis of Maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp.) from Xinjiang and Its Antifatigue Activity. J. Food Qual. 2017, 2017, 2904951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Jin, L.; Xie, L.; Huang, J.; Wang, N.; Chu, B.; Dai, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y. Structural Characterization and Antifatigue Effect In Vivo of Maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp) Polysaccharide. J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Jin, W.; Lv, X.; Dai, P.; Ao, Y.; Wu, M.; Deng, W.; Yu, L. Effects of Macamides on Endurance Capacity and Anti-Fatigue Property in Prolonged Swimming Mice. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 54, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, B.L.; He, K.; Hwang, Z.Y.; Lu, Y.; Yan, S.J.; Kim, C.H.; Zheng, Q.Y. Effect of Aqueous Extract from Lepidium meyenii on Mouse Behavior in Forced Swimming Test. In Quality Management of Nutraceuticals; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; Volume 803, pp. 258–268. ISBN 9780841237735. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeuchi, M.; Koyama, T.; Takei, S.; Kino, T.; Yazawa, K. Effects of Benzylglucosinolate on Endurance Capacity in Mice. J. Health Sci. 2009, 55, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, W.-C.; Wu, Z.-Y.; Fu, C.-X.; Hui, A.-L.; Gao, H.; Chen, P.-P.; Du, B.; Zhang, H.-W. Two Macamide Extracts Relieve Physical Fatigue by Attenuating Muscle Damage in Mice. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 1405–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yábar, E.; Chirinos, R.; Campos, D. Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity in Three Maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp.) Ecotypes during Pre-Harvest, Harvest and Natural Post-Harvest Drying. Sci. Agropecu. 2019, 10, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozakowska, M.; Pietraszek-Gremplewicz, K.; Jozkowicz, A.; Dulak, J. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Skeletal Muscle Injury and Regeneration: Focus on Antioxidant Enzymes. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2015, 36, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, J.M.; Da Silva-Grigoletto, M.E.; Túnez-Fiñana, I. Estrés Oxidativo Inducido Por El Ejercicio. Rev. Andal. Med. Deport 2009, 2, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, M.; Kawabata, K.; Sato, K.; Yamaguchi, S.; Hachiya, A.; Takahashi, Y.; Inoue, S. Glutathione Maintenance Is Crucial for Survival of Melanocytes after Exposure to Rhododendrol. Pigment. Cell Melanoma Res. 2016, 29, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varra, F.-N.; Gkouzgos, S.; Varra, M.; Theodosis-Nobelos, P. Efficacy of Antioxidant Compounds in Obesity and Its Associated Comorbidities. Pharmakeftiki 2024, 36, 2–19. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.E.; Stopper, A.R. Amino Acids|Glutathione. In Encyclopedia of Biological Chemistry III, 3rd ed.; Jez, J., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 71–78. ISBN 978-0-12-822040-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ulasov, A.V.; Rosenkranz, A.A.; Georgiev, G.P.; Sobolev, A.S. Nrf2/Keap1/ARE Signaling: Towards Specific Regulation. Life Sci. 2022, 291, 120111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Dashwood, R.H. Epigenetic Regulation of NRF2/KEAP1 by Phytochemicals. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakkittukandiyil, A.; Sajini, D.V.; Karuppaiah, A.; Selvaraj, D. The Principal Molecular Mechanisms behind the Activation of Keap1/Nrf2/ARE Pathway Leading to Neuroprotective Action in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurochem. Int. 2022, 156, 105325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yang, Z.; Xu, W.; Chen, Q. The Applications and Mechanisms of Superoxide Dismutase in Medicine, Food, and Cosmetics. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, R.; Namdeo, M. Superoxide Dismutase: A Key Enzyme for the Survival of Intracellular Pathogens in Host. In Reactive Oxygen Species; Ahmad, R., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher-Wellman, K.; Bloomer, R.J. Acute Exercise and Oxidative Stress: A 30 Year History. Dyn. Med. 2009, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.-C.; Tsai, S.-C.; Lin, W.-T. Potential Ergogenic Effects of L-Arginine against Oxidative and Inflammatory Stress Induced by Acute Exercise in Aging Rats. Exp. Gerontol. 2008, 43, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Y. Polysaccharides from Cordyceps Sinensis Mycelium Ameliorate Exhaustive Swimming Exercise-Induced Oxidative Stress. Pharm. Biol. 2014, 52, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Chávez, J.; Villa, J.A.; Fernando Ayala-Zavala, J.; Basilio Heredia, J.; Sepulveda, D.; Yahia, E.M.; González-Aguilar, G.A. Technologies for Extraction and Production of Bioactive Compounds to Be Used as Nutraceuticals and Food Ingredients: An Overview. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2013, 12, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.Y.; Joung, J.A.; Baek, S.J.; Chen, J.; Choi, J.H. Simultaneous Extraction of Proteins and Carbohydrates, Including Phenolics, Antioxidants, and Macamide B from Peruvian Maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp.). Korean J. Food Preserv. 2021, 28, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyanbadrakh, E.; Hong, H.S.; Lee, K.W.; Huang, W.Y.; Oh, J.H. Antioxidant Activity, Macamide B Content and Muscle Cell Protection of Maca (Lepidium meyenii) Extracted Using Ultrasonification-Assisted Extraction. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Lett. 2020, 48, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, S.; Durango-Zuleta, M.M.; Felipe Osorio-Tobón, J. Techno-Economic Evaluation of the Extraction of Anthocyanins from Purple Yam (Dioscorea alata) Using Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction and Conventional Extraction Processes. Food Bioprod. Process. 2020, 122, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crupi, P. Special Issue on “Technologies for Production, Processing, and Extractions of Nature Product Compounds”. Processes 2023, 11, 2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yábar Villanueva, E.; Reyes De La Cruz, V. La Maca (Lepidium meyenii Walpers) Alimento Funcional Andino: Bioactivos, Bioquímica y Actividad Biológica. Rev. Investig. Altoandinas—J. High. Andean Res. 2019, 21, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Hu, B.; Hua, H.; Liu, C.; Cheng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yao, W.; Qian, H. Macamides: A Review of Structures, Isolation, Therapeutics and Prospects. Food Res. Int. 2020, 138, 109819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva Leitão Peres, N.; Cabrera Parra Bortoluzzi, L.; Medeiros Marques, L.L.; Formigoni, M.; Fuchs, R.H.B.; Droval, A.A.; Reitz Cardoso, F.A. Medicinal Effects of Peruvian Maca (Lepidium meyenii): A Review. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uto-Kondo, H.; Naito, Y.; Ichikawa, M.; Nakata, R.; Hagiwara, A.; Kotani, K. Antioxidant Activity, Total Polyphenol, Anthocyanin and Benzyl-Glucosinolate Contents in Different Phenotypes and Portion of Japanese Maca (Lepidium meyenii). Heliyon 2024, 10, e32778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhu, F. Chemical Composition and Health Effects of Maca (Lepidium meyenii). Food Chem. 2019, 288, 422–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neilson, L.E.; Quinn, J.F.; Gray, N.E. Peripheral Blood NRF2 Expression as a Biomarker in Human Health and Disease. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe-Fuentes, I.; Vega-Gálvez, A.; Campos-Requena, V.H. Antioxidant Compound Extraction from Maqui (Aristotelia Chilensis [Mol] Stuntz) Berries: Optimization by Response Surface Methodology. Antioxidants 2017, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, A.; Hermosín-Gutiérrez, I.; Mardones, C.; Vergara, C.; Herlitz, E.; Vega, M.; Dorau, C.; Winterhalter, P.; von Baer, D. Polyphenols and Antioxidant Activity of Calafate (Berberis Microphylla) Fruits and Other Native Berries from Southern Chile. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 6081–6089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escribano-Bailón, M.T.; Alcalde-Eon, C.; Muñoz, O.; Rivas-Gonzalo, J.C.; Santos-Buelga, C. Anthocyanins in Berries of Maqui [Aristotelia Chilensis (Mol.) Stuntz]. Phytochem. Anal. 2006, 17, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honma, A.; Fujiwara, Y.; Takei, S.; Kino, T. The Improvement of Daily Fatigue in Women Following the Intake of Maca (Lepidium meyenii) Extract Containing Benzyl Glucosinolate. Funct. Foods Health Dis. 2022, 12, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Objective | LmW Types Used in Studies | Phytochemical Compounds * | Bioactive Components |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro research | ||||

| Zhu et al. [40] | To investigate the role of AEM on muscle during exercise-induced fatigue both in vivo and in vitro | Aqueous extract of black Maca | Flavan-3-ol derivatives Polysaccharide Total polyphenol Total flavonoids | Total polysaccharide 19.72 mg/mL Reducing sugar 2.87 mg/mL Total protein 2.62 mg/mL Total amino acids 7.87 mg/mL Total fatty acids 1.17 mg/mL Total polyphenol 16.60 μg/mL Total flavonoids 21.40 μg/mL |

| Zhu et al. [41] | To explore the underlying mechanism of the Maca compound preparation, a prescription for the management of exercise-induced fatigue | Maca compound preparation | Flavan-3-ol derivatives Polysaccharide Total polyphenol Total flavonoids | Total polysaccharides 34.78 ± 2.43 mg/mL Flavonoids 0.15 ± 0.01 mg/mL Total amino acids 1845.27 ± 10.92 mg/mL |

| In vivo research (animals) | ||||

| Choi et al. [42] | To investigate the effect of standardized lipid-soluble extract obtained by supercritical fluid extraction of Maca on swimming endurance capacity, serum biochemical parameters, and antioxidant status in a weight-loaded forced swimming rat model | Lipid soluble extract of yellow Maca | Flavan-3-ol derivatives N-benzyl-5-oxo-6E,8E-oc-tadecadienamide N-benzyl-hexadecanamide | Water 29.7% Fatty acids 10.8% (2.58% palmitic acid, 1.85% oleic acid, 3.55% linoleic acid, and 1.75% linolenic acid) 0.7% sterols (b-sitosterol and campesterol) Total phenolic content 26.5 mg/g Macamides 7.8 mg/g (N-benzylhexadecanamide and N-benzyl-5-oxo-6E,8E-octadecadienamide) |

| He et al. [43] | To investigate the effects of polysaccharides from Maca on oxidative damage induced by exhaustive swimming exercise using rat models | Polysaccharides from Maca | Flavan-3-ol derivatives | 2.37% weight/weight of dried roots of Maca |

| Li et al. [44] | To investigate the anti-physical fatigue effect of polysaccharides from Maca and the possible mechanisms | Polysaccharides from yellow Maca | Flavan-3-ol derivatives Polysaccharides (7.6 and 6.7 kDa) | 2.37% weight/weight of dried roots of Maca |

| Orhan et al. [13] | To see whether a new MPB form affected serum, muscle, and liver oxidant and antioxidant responses, anti-fatigue, endurance capacity, and especially mitochondrial biogenesis-associated proteins in exhaustion-exposed rats | Powder blend of red and black Maca (ratio 4:1) | Flavan-3-ol derivatives Benzoic acid derivative | Undeclared |

| Tang et al. [45] | To investigate the antifatigue effect of MP by using a mouse weight-loaded swimming model to provide a theoretical basis and practical guidance for the comprehensive exploration of MP | Polysaccharides from Lepidium meyenii Walp | Flavan-3-ol derivatives Polysaccharide (D-GalA-riched) | D-GalA (35.07%), D-Glc (29.98%), L-Ara (16.98%), D-Man (13.01%), D-Gal (4.21%), and L-Rha (0.75%) |

| Yang et al. [46] | To investigate the effects of macamides on endurance capacity and anti-fatigue properties in prolonged swimming mice | Macamides from Lepidium meyenii Walp | Flavan-3-ol derivatives N-benzyl-oleamide N-benzyl-linoleamide | low-dose group of N-benzyllinoleamide (12 mg/kg), high-dose group of N-benzyllinoleamide (40 mg/kg), low-dose group of N-benzyloleamide (12 mg/kg), high-dose group of N-benzyloleamide (40 mg/kg), low-dose group of N-benzylpalmitamide (12 mg/kg), and high-dose group of N-benzylpalmitamide (40 mg/kg). |

| Zheng et al. [47] | To investigate the activity of energy enhancement of aqueous extracts from roots of Maca on the behavior in mice using FST | Aqueous extract of yellow Maca | Flavan-3-ol derivatives Benzyl-isothiocyanate Polysaccharides | MacaForceTM AQ-2 contains 0.18% benzyl-isothiocyanate, 0.019% sterols (0.006% campesterol, 0.003% stigmasterol, and 0.010% β-sitosterol), 1.11% fatty acids (0.28% capric acid, 0.2% lauric acid, 0.19% palmitic acid, 0.02% stearic acid, 0.06% oleic acid, 0.24% linoleic acid, and 0.12% linolenic acid), 5.97% amino acids (0.145% alanine, 0.374% arginine, 0.139% aspartic acid, 0.252% glutamic acid, 0.060% glycine, 0.030% histidine, 0.039% isoleucine, 0.038% leucine, 0.031% lysine, 0.013% methionine, 4.630% proline, 0.028% serine, 0.052% threonine, 0.019% tyrosine, and 0.115% valine), 21.0% polysaccharide (hydrolyzable carbohydrate: 1.20% glucose, 4.45% fructose, and 15.3% sucrose), and 0.27% macaene and macamides |

| Zhu et al. [40] | To investigate the role of AEM on muscle during exercise-induced fatigue both in vivo and in vitro | Aqueous extract of black Maca | Flavan-3-ol derivatives Polysaccharide Total polyphenol Total flavonoids | Total polysaccharide 19.72 mg/mL Reducing sugar 2.87 mg/mL Total protein 2.62 mg/mL Total amino acids 7.87 mg/mL Total fatty acids 1.170 mg/mL Total polyphenol 16.60 μg/mL Total flavonoids 21.4 μg/mL |

| Zhu et al. [41] | To explore the underlying mechanism of the MCP, a prescription for management of exercise-induced fatigue | Maca compound preparation | Flavan-3-ol derivatives Polysaccharide Total polyphenol Total flavonoids | Total polysaccharides 34.78 ± 2.43 mg/mL Flavonoids 0.15 ± 0.01 mg/mL Total amino acids 1845.27 ± 10.92 mg/mL |

| Authors | Participants or Sample | IV | DV | Test | Supplementation Protocol | Results | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro research | |||||||

| Zhu et al. [40] | C2C12 cells (n = 96) | EG: AEM + oxidative stress induced by H2O2 | PO: ROS | Fluorescence intensity, analysis of mitochondrial networks, analysis of mitochondrial network size, analysis of mitochondrial bench length, and analysis of mitochondrial footprint | AEM EG1: 100 μg/mL Positive drug EG2: 100 μg/mL caffeine CG1: normal incubation CG2: normal incubation + H2O2 | ROS (fluorescence intensity): CG2 = 1164 ± 74 vs. CG1 = 323 ± 64; p < 0.05 EG1 = 847 ± 71 vs. CG1 = 323 ± 64; p < 0.05 EG1 = 847 ± 71 vs. CG2 = 1164 ± 74; p < 0.05 EG2 = 842 ± 63 vs. CG1 = 323 ± 64; p < 0.05 EG2 = 842 ± 63 vs. CG2 = 1164 ± 74; p < 0.05 | ROS (fluorescence intensity): CG2 vs. CG1 ↑ EG1 vs. CG1 ↑ EG1 vs. CG2 ↓ EG2 vs. CG1 ↑ EG1 vs. CG2 ↓ |

| Zhu et al. [41] | C2C12 cells (n = 5) | EG: Maca compound preparation + oxidative stress induced by H2O2 | PO: ROS | Fluorescent probe, luminescence, and mitochondrial membrane potential assay | MCP EG1: 100 μg/mL EG2: 500 μg/mL EG3: 1000 μg/mL EG4: 100 μg/mL caffeine CG1: incubated in standard conditions CG2: incubated in standard conditions + H2O2 | ROS (U/mL): CG2 = 1160 ± 70 vs. CG1 = 375 ± 16; p < 0.01 EG1 = 860 ± 20 vs. CG1 = 375 ± 16; p < 0.01 EG1 = 860 ± 20 vs. CG2 = 1160 ± 70; p < 0.01 EG2 = 710 ± 40 vs. CG1 = 375 ± 16; p < 0.01 EG2 = 710 ± 40 vs. CG2 = 1160 ± 70; p < 0.01 EG3 = 710 ± 30 vs. CG1 = 375 ± 16; p < 0.01 EG3 = 710 ± 30 vs. CG2 = 1160 ± 70; p < 0.01 EG4 = 800 ± 45 vs. CG1 = 375 ± 16; p < 0.01 EG4 = 800 ± 45 vs. CG2 = 1160 ± 70; p < 0.01 | ROS (U/mL): CG2 vs. CG1 ↓ EG1 vs. CG1 ↓ EG1 vs. CG2 ↑ EG2 vs. CG1 ↓ EG2 vs. CG2 ↑ EG3 vs. CG1 ↓ EG3 vs. CG2 ↑ EG4 vs. CG1 ↓ EG4 vs. CG2 ↑ |

| In vivo research (animals) | |||||||

| Choi et al. [42] | Mice: EG1 (n = 20) EG2 (n = 20) CG (n = 20) | EG1 and EG2: Lipid-soluble Maca extract CG: PL | PO: TBARS, GSH, catalase, and SOD | FST: Bio: Liver and hind limb | Lipid soluble Maca extract: EG1: 30 mg/10 mL/kg EG2: 100 mg/10 mL/kg CG: 10 mL/kg sterile water | TBARS l (nmol/g): EG1 = 19.6 ± 1.0 vs. CG = 19.8 ± 0.8; p > 0.05 EG2 = 17.3 ± 0.7 vs. CG = 19.8 ± 0.8; p < 0.05 TBARS m (nmol/g): EG1 = 41.5 ± 1.6 vs. CG = 40.5 ± 2.0; p > 0.05 EG2 = 41.4 ± 0.6 vs. CG = 40.5 ± 2.0; p > 0.05 GSH l (μmol/g): EG1 = 1.08 ± 0.03 vs. CG = 1.02 ± 0.03; p > 0.05 EG2 = 1.12 ± 0.02 vs. CG = 1.02 ± 0.03; p < 0.05 GSH m (μmol/g): EG1 = 7.04 ± 0.20 vs. CG = 7.03 ± 0.17; p > 0.05 EG2 = 7.65 ± 0.16 vs. CG = 7.03 ± 0.17; p < 0.05 SOD l (U/mg): EG1 = 7.99 ± 0.21 vs. CG = 8.08 ± 0.23; p > 0.05 EG2 = 8.23 ± 0.20 vs. CG = 8.08 ± 0.23; p > 0.05 SOD m (U/mg): EG1 = 33.9 ± 0.76 vs. CG = 32.3 ± 0.43; p > 0.05 EG2 = 33.0 ± 0.70 vs. CG = 32.3 ± 0.43; p > 0.05 Catalase muscle (μmol/min/mg): EG1 = 0.021 ± 0.001 vs. CG = 0.019 ± 0.001; p > 0.05 EG2 = 0.019 ± 0.001 vs. CG = 0.019 ± 0.001; p > 0.05 Catalase liver (μmol/min/mg): EG1 = 1.76 ± 0.03 vs. CG = 1.65 ± 0.06; p > 0.05 EG2 = 2.09 ± 0.05 vs. CG = 1.65 ± 0.06; p < 0.05 | TBARS (nmol/g): EG1 vs. CG ↔ EG2 vs. CG ↑ TBARS (nmol/g): EG1 vs. CG ↔ EG2 vs. CG ↔ GSH (μmol/g): EG1 vs. CG ↔ EG2 vs. CG ↓ GSH (μmol/g): EG1 vs. CG ↔ EG2 vs. CG ↓ SOD (U/mg): EG1 vs. CG ↔ EG2 vs. CG ↔ SOD liver (U/mg): EG1 vs. CG ↔ EG2 vs. CG ↔ Catalase muscle (μmol/min/mg): EG1 vs. CG ↔ EG2 vs. CG ↔ Catalase liver (μmol/min/mg): EG1 vs. CG ↔ EG2 vs. CG ↑ |

| He et al. [43] | Mice: EG1 (n = 10) EG2 (n = 10) EG3 (n = 10) CG1 (n = 10) CG2 (n = 10) | EG: MP CG: PL | PO: MDA, GPx, GSH, and SOD | FST | MP EG1: exercise + 50 mg/kg EG2: exercise + 100 mg/kg EG3: exercise + 200 mg/kg CG1: sedentary + distilled water CG2: exercise + distilled water | MDA m (nmol/mg): EG1 = 2.72 ± 0.18 vs. CG1 = 1.8 ± 0.45; p < 0.05 EG1 = 2.72 ± 0.18 vs. CG2 = 3.1 ± 0.50; p < 0.05 EG2 = 2.25 ± 0.75 vs. CG1 = 1.8 ± 0.45; p < 0.05 EG2 = 2.25 ± 0.75 vs. CG2 = 3.1 ± 0.50; p < 0.05 EG3 = 2.37 ± 0.37 vs. CG1 = 1.8 ± 0.45; p < 0.05 EG3 = 2.37 ± 0.37 vs. CG2 = 3.1 ± 0.50; p < 0.05 CG1 = 1.80 ± 0.45 vs. CG2 = 3.1 ± 0.50; p < 0.05 GPx m (U/mg): EG1 = 12.0 ± 1.9 vs. CG1 = 17.2 ± 3.1; p < 0.05 EG1 = 12.0 ± 1.9 vs. CG2 = 8.3 ± 3.5; p < 0.05 EG2 = 14.7 ± 2.7 vs. CG1 = 17.2 ± 3.1; p < 0.05 EG2 = 14.7 ± 2.7 vs. CG2 = 8.3 ± 3.5; p < 0.05 EG3 = 16.1 ± 3.6 vs. CG1 = 17.2 ± 3.1; p > 0.05 EG3 = 16.1 ± 3.6 vs. CG2 = 8.3 ± 3.5; p < 0.05 CG1 = 17.2 ± 3.1 vs. CG2 = 8.3 ± 3.5; p < 0.05 GSH m (mmol/g): EG1 = 2.38 ± 0.42 vs. CG1 = 3.2 ± 0.55; p < 0.05 EG1 = 2.38 ± 0.42 vs. CG2 = 2.0 ± 0.38; p < 0.05 EG2 = 2.61 ± 0.19 vs. CG1 = 3.2 ± 0.55; p < 0.05 EG2 = 2.61 ± 0.19 vs. CG2 = 2.0 ± 0.38; p < 0.05 EG3 = 2.95 ± 0.55 vs. CG1 = 3.2 ± 0.55; p > 0.05 EG3 = 2.95 ± 0.55 vs. CG2 = 2.0 ± 0.38; p < 0.05 CG1 = 3.20 ± 0.55 vs. CG2 = 2.0 ± 0.38; p < 0.05 SOD m (U/mg): EG1 = 143 ± 29 vs. CG1 = 188 ± 34; p < 0.05 EG1 = 143 ± 29 vs. CG2 = 114 ± 21; p < 0.05 EG2 = 157 ± 33 vs. CG1 = 188 ± 34; p < 0.05 EG2 = 157 ± 33 vs. CG2 = 114 ± 21; p < 0.05 EG3 = 174 ± 24 vs. CG1 = 188 ± 34; p > 0.05 EG3 = 174 ± 24 vs. CG2 = 114 ± 21; p < 0.05 CG1 = 188 ± 34 vs. CG2 = 114 ± 21; p < 0.05 | MDA (nmol/mg): EG1 vs. CG1 ↑ EG1 vs. CG2 ↓ EG2 vs. CG1 ↑ EG2 vs. CG2 ↓ EG3 vs. CG1 ↑ EG3 vs. CG2 ↓ CG1 vs. CG2 ↓ GPx (U/mg): EG1 vs. CG1 ↓ EG1 vs. CG2 ↑ EG2 vs. CG1 ↓ EG2 vs. CG2 ↑ EG3 vs. CG1 ↔ EG3 vs. CG2 ↑ CG1 vs. CG2 ↑ GSH (mmol/g): EG1 vs. CG1 ↓ EG1 vs. CG2 ↑ EG2 vs. CG1 ↓ EG2 vs. CG2 ↑ EG3 vs. CG1 ↔ EG3 vs. CG2 ↑ CG1 vs. CG2 ↑ SOD (U/mg): EG1 vs. CG1 ↓ EG1 vs. CG2 ↑ EG2 vs. CG1 ↓ EG2 vs. CG2 ↑ EG3 vs. CG1 ↔ EG3 vs. CG2 ↑ CG1 vs. CG2 ↑ |

| Li et al. [44] | Mice: EG1 (n = 12) EG2 (n = 12) EG3 (n = 12) CG (n = 12) | EG: MP CG: PL | PO: MDA, GPx, and SOD | FST Bio: Liver | MP EG1: 500 mg/kg EG2: 1000 mg/kg EG3: 2000 mg/kg CG: distilled water | MDA l (mmol/mg): EG1 = 7.40 ± 0.98 vs. CG = 8.48 ± 1.13; p < 0.05 EG2 = 7.15 ± 0.55 vs. CG = 8.48 ± 1.13; p < 0.05 EG3 = 6.50 ± 0.77 vs. CG = 8.48 ± 1.13; p < 0.05 GPx l (U/mg): EG1 = 59.4 ± 7.1 vs. CG = 56.2 ± 8.7; p > 0.05 EG2 = 67.5 ± 10.1 vs. CG = 56.2 ± 8.7; p < 0.05 EG3 = 74.9 ± 7.6 vs. CG = 56.2 ± 8.7; p < 0.05 SOD l (U/mg): EG1 = 44.3 ± 6.2 vs. CG = 34.5 ± 5.5; p < 0.05 EG2 = 51.8 ± 8.7 vs. CG = 34.5 ± 5.5; p < 0.05 EG3 = 58.3 ± 9.2 vs. CG = 34.5 ± 5.5; p < 0.05 | MDA (mmol/mg): EG1 vs. CG ↑ EG2 vs. CG ↑ EG3 vs. CG ↑ GPx (U/mg): EG1 vs. CG ↔ EG2 vs. CG ↑ EG3 vs. CG ↔ SOD (U/mg): EG1 vs. CG ↑ EG2 vs. CG ↑ EG3 vs. CG ↑ |

| Orhan et al. [13] | Mice: EG1 (n = 7) EG2 (n = 7) CG1 (n = 7) CG2 (n = 7) | EG: MPB and MPB + FST CG: PL and PL + FST | PO: serum MDA, liver MDA, muscle MDA, liver GPx, muscle GPx, liver SOD, and muscle SOD | FST Bio: Liver | MPB EG1: 40 mg/kg EG2: 40 mg/kg of MPB + FST CG1: 1 mL of water CG2: 1 mL of water + FST | Serum MDA (μmol/L): EG1 = 0.44 ± 0.04 vs. CG1 = 0.71 ± 0.03; p < 0.01 EG1 = 0.44 ± 0.04 vs. CG2 = 1.60 ± 0.06; p < 0.001 EG2 = 1.17 ± 0.04 vs. CG1 = 0.71 ± 0.03; p < 0.001 EG2 = 1.17 ± 0.04 vs. CG2 = 1.60 ± 0.06; p < 0.001 CG1 = 0.71 ± 0.03 vs. CG2 = 1.60 ± 0.06; p < 0.001 MDA l (nmol/g): EG1 = 1.64 ± 0.06 vs. CG1 = 2.10 ± 0.11; p < 0.05 EG1 = 1.64 ± 0.06 vs. CG2 = 3.28 ± 0.10; p < 0.001 EG2 = 2.52 ± 0.12 vs. CG1 = 2.10 ± 0.11; p < 0.05 EG2 = 2.52 ± 0.12 vs. CG2 = 3.28 ± 0.10; p < 0.001 CG1 = 2.10 ± 0.11 vs. CG2 = 3.28 ± 0.10; p < 0.001 MDA m (nmol/g): EG1 = 1.18 ± 0.05 vs. CG1 = 1.57 ± 0.06; p < 0.001 EG1 = 1.18 ± 0.05 vs. CG2 = 2.53 ± 0.06; p < 0.001 EG2 = 2.04 ± 0.05 vs. CG1 = 1.57 ± 0.06; p < 0.001 EG2 = 2.04 ± 0.05 vs. CG2 = 2.53 ± 0.06; p < 0.001 CG1 = 1.57 ± 0.06 vs. CG2 = 2.53 ± 0.006; p < 0.001 GPx l (U/mg): EG1 = 120.93 ± 2.09 vs. CG1 = 116.32 ± 2.28; p > 0.05 EG1 = 120.93 ± 2.09 vs. CG2 = 106.57 ± 2.06; p < 0.01 EG2 = 113.08 ± 2.09 vs. CG1 = 116.32 ± 2.28; p > 0.05 EG2 = 113.08 ± 2.09 vs. CG2 = 106.57 ± 2.06; p > 0.05 CG1 = 116.32 ± 2.28 vs. CG2 = 106.57 ± 2.06; p < 0.05 GPx m (U/mg): EG1 = 14.08 ± 0.38 vs. CG1 = 11.10 ± 0.38; p < 0.001 EG1 = 14.08 ± 0.38 vs. CG2 = 6.26 ± 0.11; p < 0.001 EG2 = 8.99 ± 0.25 vs. CG1 = 11.10 ± 0.38; p < 0.001 EG2 = 8.99 ± 0.25 vs. CG2 = 6.26 ± 0.11; p < 0.001 CG1 = 11.10 ± 0.38 vs. CG2 = 6.26 ± 0.11; p < 0.001 SOD l (U/mg): EG1 = 91.47 ± 2.29 vs. CG1 = 85.64 ± 2.46; p > 0.05 EG1 = 91.47 ± 2.29 vs. CG2 = 71.02 ± 2.08; p < 0.001 EG2 = 78.22 ± 2.58 vs. CG1 = 85.64 ± 2.46; p > 0.05 EG2 = 78.22 ± 2.58 vs. CG2 = 71.02 ± 2.08; p > 0.05 CG1 = 85.64 ± 2.46 vs. CG2 = 71.02 ± 2.08; p < 0.01 SOD m (U/mg): EG1 = 84.89 ± 2.76 vs. CG1 = 79.40 ± 1.74; p > 0.05 EG1 = 84.89 ± 2.76 vs. CG2 = 71.64 ± 1.14; p < 0.01 EG2 = 75.79 ± 2.32 vs. CG1 = 79.40 ± 1.74; p > 0.05 EG2 = 75.79 ± 2.32 vs. CG2 = 71.64 ± 1.14; p > 0.05 CG1 = 79.40 ± 1.74 vs. CG2 = 71.64 ± 1.14; p > 0.05 | Serum MDA (μmol/L): EG1 vs. CG1 ↑ EG1 vs. CG2 ↑ EG2 vs. CG1 ↓ EG2 vs. CG2 ↑ CG1 vs. CG2 ↑ MDA l (nmol/g): EG1 vs. CG1 ↑ EG1 vs. CG2 ↑ EG2 vs. CG1 ↓ EG2 vs. CG2 ↓ CG1 vs. CG2 ↑ MDA m (nmol/g): EG1 vs. CG1 ↑ EG1 vs. CG2 ↑ EG2 vs. CG1 ↑ EG2 vs. CG2 ↑ CG1 vs. CG2 ↑ GPx l (U/mg): EG1 vs. CG1 ↔ EG1 vs. CG2 ↑ EG2 vs. CG1 ↔ EG2 vs. CG2 ↔ CG1 vs. CG2 ↑ GPx m (U/mg): EG1 vs. CG1 ↑ EG1 vs. CG2 ↑ EG2 vs. CG1 ↓ EG2 vs. CG2 ↑ CG1 vs. CG2 ↑ SOD l (U/mg): EG1 vs. CG1 ↔ EG1 vs. CG2 ↑ EG2 vs. CG1 ↔ EG2 vs. CG2 ↔ CG1 vs. CG2 ↑ SOD m (U/mg): EG1 vs. CG1 ↔ EG1 vs. CG2 ↑ EG2 vs. CG1 ↔ EG2 vs. CG2 ↔ CG1 vs. CG2 ↔ |

| Tang et al. [45] | Mice: EG1 (n = 20) EG2 (n = 20) EG3 (n = 20) CG (n = 20) | EG: MP CG: PL | PO: MDA and GSH-Px | FST | MP EG1: 100 mg/kg EG2: 50 mg/kg EG3: 25 mg/kg CG: distilled water | Serum MDA (nmol/mg): EG1 = 4.53 ± 1.33 vs. CG = 5.05 ± 0.38; p > 0.05 EG2 = 4.81 ± 1.12 vs. CG = 5.05 ± 0.38; p > 0.05 EG3 = 3.98 ± 0.65 vs. CG = 5.05 ± 0.38; p < 0.01 Serum GSH-Px (μmol/L): EG1 = 510 ± 115 vs. CG = 505 ± 22; p > 0.05 EG2 = 612 ± 174 vs. CG = 505 ± 22; p < 0.05 EG3 = 593 ± 45 vs. CG = 505 ± 22; p < 0.05 | MDA (nmol/mg): EG1 vs. CG ↔ EG2 vs. CG ↔ EG3 vs. CG ↑ GSH-Px (μmol/L): EG1 vs. CG ↔ EG2 vs. CG ↑ EG3 vs. CG ↑ |

| Yang et al. [46] | Mice: EG1 (n = 10) EG2 (n = 10) EG3 (n = 10) EG4 (n = 10) EG5 (n = 10) EG6 (n = 10) CG (n = 10) | EG: Maca extract (N-benzyllinoleamide, N-benzyl oleamide and N-benzylpalmitamide) CG: PL | PO: MDA, GSH-Px, and SOD SO: glucose | FST Bio: liver | N-benzyllinoleamide EG1: 12 mg/10mL/kg EG2: 40 mg/10 mL/kg N-benzyl oleamide EG3: 12 mg/10 mL/kg EG4: 40 mg/10 mL/kg N-benzylpalmitamide EG5: 12 mg/10 mL/kg EG6: 40 mg/10 mL/kg CG: distilled water | MDA b (nmol/mgprot): EG1 = 3.03 ± 0.74 vs. CG = 3.20 ± 0.74; p > 0.05 EG2 = 2.58 ± 0.52 vs. CG = 3.20 ± 0.74; p < 0.05 EG3 = 3.04 ± 0.49 vs. CG = 3.20 ± 0.74; p > 0.05 EG4 = 2.43 ± 0.64 vs. CG = 3.20 ± 0.74; p < 0.01 EG5 = 3.06 ± 1.49 vs. CG = 3.20 ± 0.74; p > 0.05 EG6 = 3.29 ± 0.83 vs. CG = 3.20 ± 0.74; p > 0.05 MDA m (nmol/mgprot): EG1 = 2.68 ± 0.35 vs. CG = 2.83 ± 0.26; p > 0.05 EG2 = 2.39 ± 0.32 vs. CG = 2.83 ± 0.26; p < 0.05 EG3 = 2.61 ± 0.38 vs. CG = 2.83 ± 0.26; p > 0.05 EG4 = 2.43 ± 0.31 vs. CG = 2.83 ± 0.26; p < 0.05 EG5 = 3.05 ± 0.43 vs. CG = 2.83 ± 0.26; p > 0.05 EG6 = 2.92 ± 0.35 vs. CG = 2.83 ± 0.26; p > 0.05 MDA l (nmol/mgprot): EG1 = 1.28 ± 0.26 vs. CG = 1.36 ± 0.22; p > 0.05 EG2 = 1.20 ± 0.18 vs. CG = 1.36 ± 0.22; p > 0.05 EG3 = 1.25 ± 0.24 vs. CG = 1.36 ± 0.22; p > 0.05 EG4 = 1.10 ± 0.32 vs. CG = 1.36 ± 0.22; p < 0.05 EG5 = 1.34 ± 0.31 vs. CG = 1.36 ± 0.22; p > 0.05 EG6 = 1.31 ± 0.43 vs. CG = 1.36 ± 0.22; p > 0.05 GSH-Px b (U/mgprot): EG1 = 44.20 ± 9.89 vs. CG = 33.23 ± 10.11; p < 0.05 EG2 = 45.35 ± 11.44 vs. CG = 33.23 ± 10.11; p < 0.05 EG3 = 42.73 ± 9.20 vs. CG = 33.23 ± 10.11; p < 0.05 EG4 = 50.12 ± 9.73 vs. CG = 33.23 ± 10.11; p < 0.01 EG5 = 33.70 ± 9.51 vs. CG = 33.23 ± 10.11; p > 0.05 EG6 = 37.32 ± 8.20 vs. CG = 33.23 ± 10.11; p > 0.05 GSH-Px m (U/mgprot): EG1 = 9.34 ± 1.02 vs. CG = 8.47 ± 0.97; p > 0.05 EG2 = 11.13 ± 1.07 vs. CG = 8.47 ± 0.97; p < 0.05 EG3 = 9.25 ± 1.13 vs. CG = 8.47 ± 0.97; p > 0.05 EG4 = 10.88 ± 0.74 vs. CG = 8.47 ± 0.97; p < 0.05 EG5 = 8.88 ± 0.87 vs. CG = 8.47 ± 0.97; p > 0.05 EG6 = 9.14 ± 0.78 vs. CG = 8.47 ± 0.97; p > 0.05 GSH-Px l (U/mgprot): EG1 = 160.06 ± 21.80 vs. CG = 152.60 ± 28.66; p > 0.05 EG2 = 176.84 ± 19.34 vs. CG = 152.60 ± 28.66; p < 0.05 EG3 = 157.14 ± 17.10 vs. CG = 152.60 ± 28.66; p > 0.05 EG4 = 180.21 ± 20.33 vs. CG = 152.60 ± 28.66; p < 0.05 EG5 = 149.46 ± 23.68 vs. CG = 152.60 ± 28.66; p > 0.05 EG6 = 161.46 ± 27.11 vs. CG = 152.60 ± 28.66; p > 0.05 SOD b (U/mgprot): EG1 = 211.40 ± 31.99 vs. CG = 180.71 ± 30.31; p < 0.05 EG2 = 207.49 ± 20.46 vs. CG = 180.71 ± 30.31; p < 0.05 EG3 = 201.66 ± 18.77 vs. CG = 180.71 ± 30.31; p < 0.01 EG4 = 217.01 ± 25.89 vs. CG = 180.71 ± 30.31; p < 0.01 EG5 = 197.51 ± 36.01 vs. CG = 180.71 ± 30.31; p > 0.05 EG6 = 201.54 ± 30.00 vs. CG = 180.71 ± 30.31; p > 0.05 SOD m (U/mgprot): EG1 = 46.39 ± 10.40 vs. CG = 47.29 ± 9.21; p > 0.05 EG2 = 60.29 ± 9.20 vs. CG = 47.29 ± 9.21; p < 0.05 EG3 = 50.11 ± 10.33 vs. CG = 47.29 ± 9.21; p > 0.05 EG4 = 58.48 ± 10.19 vs. CG = 47.29 ± 9.21; p < 0.05 EG5 = 51.35 ± 8.87 vs. CG = 47.29 ± 9.21; p > 0.05 EG6 = 53.78 ± 13.94 vs. CG = 47.29 ± 9.21; p > 0.05 SOD l (U/mgprot): EG1 = 131.73 ± 26.62 vs. CG = 110.75 ± 28.68; p > 0.05 EG2 = 142.72 ± 27.18 vs. CG = 110.75 ± 28.68; p < 0.05 EG3 = 123.22 ± 31.45 vs. CG = 110.75 ± 28.68; p > 0.05 EG4 = 145.50 ± 29.49 vs. CG = 110.75 ± 28.68; p < 0.05 EG5 = 112.51 ± 24.41 vs. CG = 110.75 ± 28.68; p > 0.05 EG6 = 118.64 ± 31.19 vs. CG = 110.75 ± 28.68; p > 0.05 Glucose (mmol/L): EG1 = 5.34 ± 0.64 vs. CG = 5.59 ± 0.78; p > 0.05 EG2 = 5.96 ± 0.95 vs. CG = 5.59 ± 0.78; p > 0.05 EG3 = 5.56 ± 0.74 vs. CG = 5.59 ± 0.78; p > 0.05 EG4 = 5.92 ± 0.83 vs. CG = 5.59 ± 0.78; p > 0.05 EG5 = 5.34 ± 0.86 vs. CG = 5.59 ± 0.78; p > 0.05 EG6 = 5.77 ± 0.70 vs. CG = 5.59 ± 0.78; p > 0.05 | MDA b (nmol/mgprot): EG1 vs. CG ↔ EG2 vs. CG ↑ EG3 vs. CG ↔ EG4 vs. CG ↑ EG5 vs. CG ↔ EG6 vs. CG ↔ MDA m (nmol/mgprot): EG1 vs. CG ↔ EG2 vs. CG ↑ EG3 vs. CG ↔ EG4 vs. CG ↑ EG5 vs. CG ↔ EG6 vs. CG ↔ MDA l (nmol/mgprot): EG1 vs. CG ↔ EG2 vs. CG ↔ EG3 vs. CG ↔ EG4 vs. CG ↑ EG5 vs. CG ↔ EG6 vs. CG ↔ GSH-Px b (U/mgprot): EG1 vs. CG ↑ EG2 vs. CG ↑ EG3 vs. CG ↑ EG4 vs. CG ↑ EG5 vs. CG ↔ EG6 vs. CG ↔ GSH-Px m (U/mgprot): EG1 vs. CG ↔ EG2 vs. CG ↑ EG3 vs. CG ↔ EG4 vs. CG ↑ EG5 vs. CG ↔ EG7 vs. CG ↔ GSH-Px l (U/mgprot): EG1 vs. CG ↔ EG2 vs. CG ↑ EG3 vs. CG ↔ EG4 vs. CG ↑ EG5 vs. CG ↔ EG6 vs. CG ↔ SOD b (U/mgprot): EG1 vs. CG ↑ EG2 vs. CG ↑ EG3 vs. CG ↑ EG4 vs. CG ↑ EG5 vs. CG ↔ EG6 vs. CG ↔ SOD m (U/mgprot): EG1 vs. CG ↔ EG2 vs. CG ↑ EG3 vs. CG ↔ EG4 vs. CG ↑ EG5 vs. CG ↔ EG6 vs. CG ↔ SOD l (U/mgprot): EG1 vs. CG ↔ EG2 vs. CG ↑ EG3 vs. CG ↔ EG4 vs. CG ↑ EG5 vs. CG ↔ EG6 vs. CG ↔ Glucose (mmol/L): EG1 vs. CG ↔ EG2 vs. CG ↔ EG3 vs. CG ↔ EG4 vs. CG ↔ EG5 vs. CG ↔ EG6 vs. CG ↔ |

| Zheng et al. [47] | Mice: EG (n = 15) CG (n = 15) | EG: MacaForceTM AQ-2 CG: PL | PO: MDA | FST | MacaForceTM AQ-2 EG: 40 mg/kg CG: 10% ethanol/water solution | Serum MDA (μmol/L): EG1 = 7.78 ± 0.43 vs. CG = 8.08 ± 0.39; p < 0.01 | MDA (μmol/L): EG vs. CG ↑ |

| Zhu et al. [40] | Mice: EG1 (n = 10) EG2 (n = 10) CG1 (n = 10) CG2 (n = 10) | EG: Maca aqueous extract (ME) and caffeine CG: PL and PL + exercise | PO: ROS in blood and ROS in muscle | RRT and GST | ME: EG1: 100 mg/kg EG2: 10 mg/kg caffeine CG1: 10 mL/kg sterile water CG2: 10 mL/kg sterile water + exercise | ROS in the blood (U/mL): EG1 = 344.6 ± 35.2 vs. CG2 = 398.5 ± 25.8; p < 0.05 EG2 = 337.5 ± 31.4 vs. CG2 = 398.5 ± 25.8; p < 0.01 CG2 = 398.5 ± 25.8 vs. CG1 = 320 ± 39.4; p < 0.01 ROS in muscle (U/mL): EG1 = 341.8 ± 15.5 vs. CG2 = 363.2 ± 5.5; p < 0.05 EG2 = 339.4 ± 10.7 vs. CG2 = 363.2 ± 5.5; p < 0.05 CG2 = 363.2 ± 5.5 vs. CG1 = 321.5 ± 11.7; p < 0.01 | ROS in the blood (U/mL): EG1 vs. CG2 ↑ EG2 vs. CG2 ↑ CG2 vs. CG1 ↓ ROS in muscle (U/mL): EG1 vs. CG2 ↑ EG2 vs. CG2 ↑ CG2 vs. CG1 ↓ |

| Zhu et al. [41] | Mice EG1 (n = 10) EG2 (n = 10) EG3 (n = 10) EG4 (n = 10) CG (n = 10) | EG: MCP CG: PL | PO: ROS | RRT and GST | MCP EG1: 1000 mg/kg MCP EG2: 2000 mg/kg MCP EG3: 4000 mg/kg MCP EG4: 10 mg/kg caffeine CG1: 1000 mg/kg sterile water CG2: 1000 mg/kg sterile water + Ex | ROS (U/mL): EG1 = 343 ± 16 vs. CG1 = 325 ± 10; p > 0.05 EG1 = 343 ± 16 vs. CG2 = 358 ± 6; p > 0.05 EG2 = 334 ± 7 vs. CG1 = 325 ± 10; p > 0.05 EG2 = 334 ± 7 vs. CG2 = 358 ± 6; p < 0.05 EG3 = 333 ± 13 vs. CG1 = 325 ± 10; p > 0.05 EG3 = 333 ± 13 vs. CG2 = 358 ± 6; p < 0.05 EG4 = 337 ± 11 vs. CG1 = 325 ± 10; p > 0.05 EG4 = 337 ± 11 vs. CG2 = 358 ± 6; p < 0.05 CG1 = 325 ± 10 vs. CG2 = 358 ± 6; p < 0.01 | ROS (U/mL): EG1 vs. CG1 ↔ EG1 vs. CG2 ↔ EG2 vs. CG1 ↔ EG2 vs. CG2 ↑ EG3 vs. CG2 ↔ EG3 vs. CG2 ↑ EG4 vs. CG1 ↔ EG4 vs. CG2 ↑ CG1 vs. CG2 ↑ |

| Authors | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choi et al. [42] | * | * | * | 0 | 0 | * | * | 0 | * | * | 7 |

| He et al. [43] | * | * | * | 0 | 0 | * | * | 0 | * | * | 7 |

| Li et al. [44] | * | * | * | 0 | 0 | * | * | 0 | * | * | 7 |

| Orhan et al. [13] | * | * | * | 0 | 0 | * | * | * | * | * | 8 |

| Tang et al. [45] | * | * | * | 0 | 0 | * | * | 0 | * | * | 7 |

| Yang et al. [46] | * | * | * | 0 | 0 | * | * | 0 | * | * | 7 |

| Zheng et al. [47] | * | 0 | * | 0 | 0 | * | * | 0 | 0 | * | 5 |

| Zhu et al. [40] | * | * | * | 0 | 0 | * | * | 0 | * | * | 7 |

| Zhu et al. [41] | * | * | * | 0 | 0 | * | * | 0 | * | * | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huerta Ojeda, Á.; Rodríguez Rojas, J.; Cuevas Guíñez, J.; Ciriza Velásquez, S.; Cancino-López, J.; Barahona-Fuentes, G.; Yeomans-Cabrera, M.-M.; Pavez, L.; Jorquera-Aguilera, C. The Effects of Maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp) on Cellular Oxidative Stress: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1046. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox13091046

Huerta Ojeda Á, Rodríguez Rojas J, Cuevas Guíñez J, Ciriza Velásquez S, Cancino-López J, Barahona-Fuentes G, Yeomans-Cabrera M-M, Pavez L, Jorquera-Aguilera C. The Effects of Maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp) on Cellular Oxidative Stress: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antioxidants. 2024; 13(9):1046. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox13091046

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuerta Ojeda, Álvaro, Javiera Rodríguez Rojas, Jorge Cuevas Guíñez, Stephanie Ciriza Velásquez, Jorge Cancino-López, Guillermo Barahona-Fuentes, María-Mercedes Yeomans-Cabrera, Leonardo Pavez, and Carlos Jorquera-Aguilera. 2024. "The Effects of Maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp) on Cellular Oxidative Stress: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Antioxidants 13, no. 9: 1046. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox13091046

APA StyleHuerta Ojeda, Á., Rodríguez Rojas, J., Cuevas Guíñez, J., Ciriza Velásquez, S., Cancino-López, J., Barahona-Fuentes, G., Yeomans-Cabrera, M.-M., Pavez, L., & Jorquera-Aguilera, C. (2024). The Effects of Maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp) on Cellular Oxidative Stress: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antioxidants, 13(9), 1046. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox13091046