Changes of Major Antioxidant Compounds and Radical Scavenging Activity of Palm Oil and Rice Bran Oil during Deep-Frying

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

2.2. Deep-Frying Model

2.3. Determination of Free Radical Scavenging Capacity

2.4. Determination of α-Tocopherol and γ-Tocotrienol

2.5. Determination of γ-Oryzanol in Rice Bran Oil

2.6. Determination of Degradation Kinetics Using the Order of Reaction Equation

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

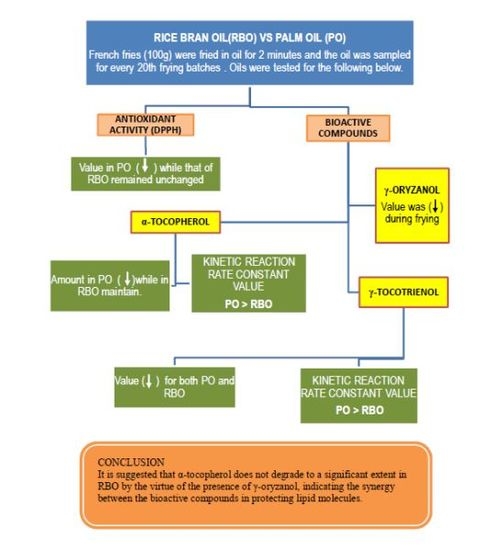

3.1. Antioxidant Capacity of the Oils

3.2. Degradation of α-Tocopherol and γ-Tocotrienol during Deep-Frying

3.3. Degradation of γ-Oryzanol in Rice Bran Oil during Deep-Frying

3.4. Degradation Kinetic of α-Tocopherol and γ-Tocotrienol during Deep-Frying

| Variable | k (min−1) | Coefficient of Determination, (r2) |

|---|---|---|

| α-tocopherol in palm oil | 0.004 | 0.961 |

| α-tocopherol in rice bran oil | 0.000 | 0.041 |

| γ-tocotrienol in palm oil | 0.006 | 0.972 |

| γ-tocotrienol in rice bran oil | 0.003 | 0.880 |

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Szydłowska-Czerniak, A.; Trokowski, K.; Karlovits, G.; Szłyk, E. Effect of refining processes on antioxidant capacity, total contents of phenolics and carotenoids in palm oils. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, M.K.; Tan, K.T.; Lee, K.T.; Mohamed, A.R. Malaysian palm oil: Surviving the food versus fuel dispute for a sustainable future. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 1456–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugano, M.; Tsuji, E. Rice bran oil and cholesterol metabolism. J. Nutr. 1997, 127, S521–S524. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Godber, J.S. Purification and identification of components of gamma-oryzanol in rice bran oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 2724–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Bhanger, M.I.; Anwar, F. Antioxidant properties and components of some commercially available varieties of rice bran in Pakistan. Food Chem. 2005, 93, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, R.A. Quantitation of steryl ferulate and p-coumarate esters from corn and rice. Lipids 1995, 30, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerma-García, M.J.; Herrero-Martínez, J.M.; Simó-Alfonso, E.F.; Mendonça, C.R.B.; Ramis-Ramos, G. Composition, industrial processing and applications of rice bran γ-oryzanol. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.; Rashid Khan, M.; Siddiqui, W.A. Comparative hypoglycemic and nephroprotective effects of tocotrienol rich fraction (TRF) from palm oil and rice bran oil against hyperglycemia induced nephropathy in type 1 diabetic rats. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2010, 188, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, L.; Theile, K.; Böhm, V. In vitro antioxidant activity of tocopherols and tocotrienols and comparison of vitamin E concentration and lipophilic antioxidant capacity in human plasma. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2010, 54, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelchowska, M.; Ambroszkiewicz, J.; Gajewska, J.; Laskowska-Klita, T.; Leibschang, J. The effect of tobacco smoking during pregnancy on plasma oxidant and antioxidant status in mother and newborn. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2011, 155, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, H.; Yoshihashi, T.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Pokorn, J. A new generation of frying oils. Czech. J. Food Sci. 2003, 21, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Yamsaengsung, R.; Moreira, R.G. Modeling the transport phenomena and structural changes during deep fat frying. Part II: Model solution & validation. J. Food Eng. 2002, 53, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, E.; Min, D.B. Chemistry of deep-fat frying oils. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, R77–R86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battino, M.; Quiles, J.L.; Huertas, J.R.; Ramirez-Tortosa, M.C.; Cassinello, M.; Mañas, M.; Lopez-Frias, M.; Mataix, J. Feeding fried oil changes antioxidant and fatty acid pattern of rat and affects rat liver mitochondrial respiratory chain components. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2002, 34, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiles, J.L.; Huertas, J.R.; Battino, M.; Ramìrez-Tortosa, M.C.; Cassinello, M.; Mataix, J.; Lopez-Frias, M.; Mañas, M. The intake of fried virgin olive or sunflower oils differentially induces oxidative stress in rat liver microsomes. Br. J. Nutr. 2002, 88, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raederstorff, D.E.; Elste, V.; Aebischer, C.; Weber, P. Effect of either γ-tocotrienol or a tocotrienol mixture on plasma lipid profile in hamster. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2002, 46, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esterhuyse, J.S.; van Rooyen, J.; Strijdom, H.; Bester, D.; du Toit, E.F. Proposed mechanisms for red palm oil induced cardioprotection in a model of hyperlipidaemia in the rat. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2006, 75, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiou, A.; Kalogeropoulos, N.; Salta, F.N.; Efstathiou, P.; Andrikopoulos, N.K. Pan-frying of French fries in three different edible oils enriched with olive leaf extract: Oxidative stability and fate of microconstituents. Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 42, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar]

- Juárez, M.D.; Osawa, C.C.; Acuña, M.E.; Sammán, N.; Gonçalves, L.A.G. Degradation in soybean oil, sunflower oil and partially hydrogenated fats after food frying, monitored by conventional and unconventional methods. Food Control 2011, 22, 1920–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou, R.; Navas, J.A.; Tres, A.; Codony, R.; Guardiola, F. Quality assessment of frying fats and fried snacks during continuous deep-fat frying at different large-scale producers. Food Control 2012, 27, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, S.; Rastogi, N.K.; Gopala Krishna, A.G.; Lokesh, B.R. Effect of frying cycles on physical, chemical and heat transfer quality of rice bran oil during deep-fat frying of poori: An Indian traditional fried food. Food Bioprod. Process. 2012, 90, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, M.T.; Becker, E.M.; Skibsted, L.H. Molecular mechanism of antioxidant synergism of tocotrienols and carotenoids in palm oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 3445–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.L.; Huang, G.W.; Liang, Z.C.; Mau, J.L. Antioxidant properties of three extracts from Pleurotus citrinopileatus. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 40, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOCS Ce 8-89. Determination of tocopherols and tocotrienols in vegetable oils and fats by HPLC. In Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists’ Society, 5th ed.; American Oil Chemists’ Society: Champaign, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Godber, J.S. Antioxidant activities of major components of γ-oryzanol from rice bran using a linoleic acid model. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2001, 78, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taoukis, P.S.; Labuza, T.P.; Saguy, I.S. Kinetics of food deterioration and shelf-life prediction. In Handbook of Food Engineering Practice; Valentas, K.J., Rotstein, E., Singh, R.P., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997; pp. 261–402. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan, M.F.; Amer, M.M.A.; Sulieman, A.E.M. Correlation between physicochemical analysis and radical scavenging activity of vegetable oil blends as affected by frying of French fries. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2006, 108, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Alonso, S.; Fregapane, G.; Salvador, M. Changes in phenolic composition and antioxidant activity of virgin olive oil during frying. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, G. The chemistry of edible fats. In The Chemistry and Technology of Edible Oils and Fats and Their High Fat Products; Hoffmann, G., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1998; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, M.; Alamprese, C.; Ratti, S. Tocopherols and tocotrienols as free radical-scavengers in refined vegetable oils and their stability during deep-fat frying. Food Chem. 2007, 102, 812–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppanen, C.M.; Song, Q.H.; Csallany, A.S. The antioxidant functions of tocopherol and tocotrienol homologues in oils, fats, and food systems. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2010, 87, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Wada, S. Enhancing the antioxidant effect of α-tocopherol with rosemary in inhibiting catalyzed oxidation caused by Fe2+ and hemoprotein. Food Res. Int. 1993, 26, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, H.; Kourimska, G.; Kourimska, L. Effect of antioxidants on losses of tocopherols during deep-fat frying. Food Chem. 1995, 52, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichenstein, A.H.; Ausman, L.M.; Carrasco, W.; Gualtieri, L.J.; Jenner, J.L.; Ordovas, J.M.; Nicolosi, R.J.; Goldin, B.R.; Schaefer, E.J. Rice bran oil consumption and plasma lipid levels in moderately hypercholesterolemic humans. Arterioscler. Thromb. 1994, 14, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetharamaiah, G.S.; Krishnakantha, T.P.; Chandrasekhara, N. Influence of oryzanol on platelet aggregation in rats. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 1990, 36, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, N.; Ausman, L.M.; Nicolosi, R.J. Oryzanol decreases cholesterol absorption and aortic fatty streaks in hamsters. Lipids 1997, 32, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, S.; Manabe, A.; Suzuki, J.; Sakamoto, K.; Inagake, T. Comparative effects of two forms of γ-oryzanol in different sterol compositions on hyperlipidemia induced by cholesterol. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1987, 44, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochhar, S.P. Stabilisation of frying oils with natural antioxidative components. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2000, 102, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotimarkorn, C.; Silalai, N. Addition of RBO to soybean oil during frying increases the oxidative stability of the fried dough from rice flour during storage. Food Res. Int. 2008, 41, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuwijitjaru, P.; Taengtieng, N.; Changprasit, S. Degradation of gamma-oryzanol in rice bran oil during heating: An analysis using derivative UV-spectrophotometry. Silpakorn Univ. Int. J. 2004, 4, 154–165. [Google Scholar]

- Nanua, J.N.; McGregor, J.U.; Godber, J.S. Influence of high-oryzanol RBO on the oxidative stability of whole milk powder. J. Dairy Sci. 2000, 83, 2426–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabliov, C.M.; Fronczek, C.; Astete, C.E.; Khachaturyan, M.; Khachatryan, L.; Leonardi, C.; Brazzoli, I. Effects of temperature and uv light on degradation of a-tocopherol in free and dissolved form. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2009, 86, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyssa, H.; Andrea, B.; Carlo, P. Kinetics of tocols degradation during the storage of einkorn (Triticum monococcum L. ssp. Monococcum) and breadwheat (Triticum aestivum L. ssp. aestivum) flours. Food Chem. 2009, 116, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.P. Preparative Techniques for Isolation of Vitamin E Homologs and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant Activities. Ph.D. Thesis, Atherns, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Hamid, A.A.; Dek, M.S.P.; Tan, C.P.; Zainudin, M.A.M.; Fang, E.K.W. Changes of Major Antioxidant Compounds and Radical Scavenging Activity of Palm Oil and Rice Bran Oil during Deep-Frying. Antioxidants 2014, 3, 502-515. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox3030502

Hamid AA, Dek MSP, Tan CP, Zainudin MAM, Fang EKW. Changes of Major Antioxidant Compounds and Radical Scavenging Activity of Palm Oil and Rice Bran Oil during Deep-Frying. Antioxidants. 2014; 3(3):502-515. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox3030502

Chicago/Turabian StyleHamid, Azizah Abdul, Mohd Sabri Pak Dek, Chin Ping Tan, Mohd Asraf Mohd Zainudin, and Evelyn Koh Wee Fang. 2014. "Changes of Major Antioxidant Compounds and Radical Scavenging Activity of Palm Oil and Rice Bran Oil during Deep-Frying" Antioxidants 3, no. 3: 502-515. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox3030502

APA StyleHamid, A. A., Dek, M. S. P., Tan, C. P., Zainudin, M. A. M., & Fang, E. K. W. (2014). Changes of Major Antioxidant Compounds and Radical Scavenging Activity of Palm Oil and Rice Bran Oil during Deep-Frying. Antioxidants, 3(3), 502-515. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox3030502