Cranberries and Cancer: An Update of Preclinical Studies Evaluating the Cancer Inhibitory Potential of Cranberry and Cranberry Derived Constituents

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

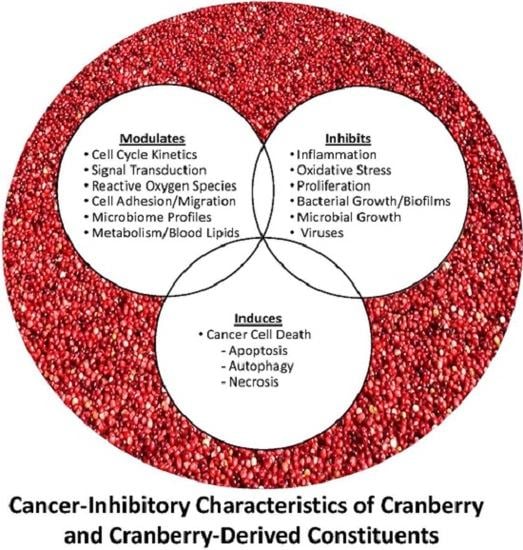

3. In Vitro Inhibition of Cancer Processes by Cranberries

3.1. Cranberry Derived Extracts and Constituents Affect Cellular Growth and Viability

3.2. Modulation of Cell Proliferation and Cell Cycle Processes by Cranberry Constituents

3.3. Cranberry Derived Extracts and Constituents Induce Cell Death Pathways

3.4. Modulation of Oxidative Status by Cranberries

3.5. Additional Biological Processes Modulated by Cranberry Derived Extracts and Constituents

3.6. In Vitro Summary

4. In Vivo Inhibition of Cancer Using Cranberry Products

4.1. Cranberry Juice Concentrate and Bladder Cancer

4.2. Colon Cancer and Cranberries

4.3. Cranberry Proanthocyanidins and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

4.4. Glioblastoma and Cranberry Derived Constituents

4.5. Non-Dialyzable Material from Cranberry Juice and Lymphoma

4.6. Prostate Cancer and Cranberry Proanthocyanidins

4.7. Whole Cranberry Extract and Stomach Cancer

4.8. In Vivo Summary

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blumberg, J.B.; Camesano, T.A.; Cassidy, A.; Kris-Etherton, P.; Howell, A.; Manach, C.; Ostertag, L.M.; Sies, H.; Skulas-Ray, A.; Vita, J.A. Cranberries and their bioactive constituents in human health. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neto, C.C. Cranberry and blueberry: Evidence for protective effects against cancer and vascular diseases. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nantz, M.P.; Rowe, C.A.; Muller, C.; Creasy, R.; Colee, J.; Khoo, C.; Percival, S.S. Consumption of cranberry polyphenols enhances human gamma delta-T cell proliferation and reduces the number of symptoms associated with colds and influenza: A randomized, placebo-controlled intervention study. Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, D.; Feldman, M.; Ofek, I.; Weiss, E.I. Cranberry high molecular weight constituents promote streptococcus sobrinus desorption from artificial biofilm. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2005, 25, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, A.B.; Foxman, B. Cranberry juice and adhesion of antibiotic-resistant uropathogens. JAMA 2002, 287, 3082–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, A.B.; Vorsa, N.; Der Marderosian, A.; Foo, L.Y. Inhibition of the adherence of p-fimbriated Escherichia coli to uroepithelial-cell surfaces by proanthocyanidin extracts from cranberries. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 1085–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, A.; Souza, D.; Roller, M.; Fromentin, E. Comparison of the anti-adhesion activity of three different cranberry extracts on uropathogenic p-fimbriated Escherichia coli: A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, ex vivo, acute study. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 1215–1218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Howell, A.B.; Botto, H.; Combescure, C.; Blanc-Potard, A.B.; Gausa, L.; Matsumoto, T.; Tenke, P.; Sotto, A.; Lavigne, J.P. Dosage effect on uropathogenic Escherichia coli anti-adhesion activity in urine following consumption of cranberry powder standardized for proanthocyanidin content: A multicentric randomized double blind study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, A.B.; Reed, J.D.; Krueger, C.G.; Winterbottom, R.; Cunningham, D.G.; Leahy, M. A-type cranberry proanthocyanidins and uropathogenic bacterial anti-adhesion activity. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 2281–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaspar, K.L.; Howell, A.B.; Khoo, C. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to assess the bacterial anti-adhesion effects of cranberry extract beverages. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 1212–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shmuely, H.; Yahav, J.; Samra, Z.; Chodick, G.; Koren, R.; Niv, Y.; Ofek, I. Effect of cranberry juice on eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients treated with antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girardot, M.; Guerineau, A.; Boudesocque, L.; Costa, D.; Bazinet, L.; Enguehard-Gueiffier, C.; Imbert, C. Promising results of cranberry in the prevention of oral Candida biofilms. Pathog. Dis. 2014, 70, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.L.; Owens, J.; Thrupp, L.; Barron, S.; Shanbrom, E.; Cesario, T.; Najm, W.I. The antifungal activity of urine after ingestion of cranberry products. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2009, 15, 957–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, E.; Schaich, K.M. Phytochemicals of cranberries and cranberry products: Characterization, potential health effects, and processing stability. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 49, 741–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, D.L.; Chen, C.Y.; Zampariello, C.A.; Blumberg, J.B. Flavonoids and phenolic acids from cranberry juice are bioavailable and bioactive in healthy older adults. Food Chem. 2015, 168, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milbury, P.E.; Vita, J.A.; Blumberg, J.B. Anthocyanins are bioavailable in humans following an acute dose of cranberry juice. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, J.M.; Ren, X.; Zampariello, C.; Polasky, D.A.; McKay, D.L.; Blumberg, J.B.; Chen, C.Y. Liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry quantification of urinary proanthocyanin a2 dimer and its potential use as a biomarker of cranberry intake. J. Sep. Sci. 2016, 39, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathison, B.D.; Kimble, L.L.; Kaspar, K.L.; Khoo, C.; Chew, B.P. Consumption of cranberry beverage improved endogenous antioxidant status and protected against bacteria adhesion in healthy humans: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr. Res. 2014, 34, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novotny, J.A.; Baer, D.J.; Khoo, C.; Gebauer, S.K.; Charron, C.S. Cranberry juice consumption lowers markers of cardiometabolic risk, including blood pressure and circulating c-reactive protein, triglyceride, and glucose concentrations in adults. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Feliciano, R.P.; Boeres, A.; Weber, T.; Dos Santos, C.N.; Ventura, M.R.; Heiss, C. Cranberry (poly)phenol metabolites correlate with improvements in vascular function: A double-blind, randomized, controlled, dose-response, crossover study. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentova, K.; Stejskal, D.; Bednar, P.; Vostalova, J.; Cihalik, C.; Vecerova, R.; Koukalova, D.; Kolar, M.; Reichenbach, R.; Sknouril, L.; et al. Biosafety, antioxidant status, and metabolites in urine after consumption of dried cranberry juice in healthy women: A pilot double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 3217–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M.A.; Ramos, S.; Mateos, R.; Marais, J.P.J.; Bravo-Clemente, L.; Khoo, C.; Goya, L. Chemical characterization and chemo-protective activity of cranberry phenolic powders in a model cell culture. Response of the antioxidant defenses and regulation of signaling pathways. Food Res. Int. 2015, 71, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, R.H. Cranberry phytochemical extracts induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2006, 241, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeram, N.P.; Adams, L.S.; Zhang, Y.J.; Lee, R.; Sand, D.; Scheuller, H.S.; Heber, D. Blackberry, black raspberry, blueberry, cranberry, red raspberry, and strawberry extracts inhibit growth and stimulate apoptosis of human cancer cells in vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 9329–9339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boivin, D.; Blanchette, M.; Barrette, S.; Moghrabi, A.; Beliveau, R. Inhibition of cancer cell proliferation and suppression of TNF-induced activation of NFKB by edible berry juice. Anticancer Res. 2007, 27, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Neto, C.C.; Krueger, C.G.; Lamoureaux, T.L.; Kondo, M.; Vaisberg, A.J.; Hurta, R.A.R.; Curtis, S.; Matchett, M.D.; Yeung, H.; Sweeney, M.I.; et al. Maldi-TOF MS characterization of proanthocyanidins from cranberry fruit (Vaccinium macrocarpon) that inhibit tumor cell growth and matrix metalloproteinase expression in vitro. J. Sci. Food. Agr. 2006, 86, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.J.; Liu, R.H. Cranberry phytochemicals: Isolation, structure elucidation, and their antiproliferative and antioxidant activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 7069–7074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, P.J.; Kurowska, E.; Freeman, D.J.; Chambers, A.F.; Koropatnick, D.J. A flavonoid fraction from cranberry extract inhibits proliferation of human tumor cell lines. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 1529–1535. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kondo, M.; MacKinnon, S.L.; Craft, C.C.; Matchett, M.D.; Hurta, R.A.; Neto, C.C. Ursolic acid and its esters: Occurrence in cranberries and other vaccinium fruit and effects on matrix metalloproteinase activity in DU145 prostate tumor cells. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, B.T.; MacKinnon, S.L.; Yan, X.J.; Hammond, G.B.; Vaisberg, A.J.; Neto, C.C. Identification of triterpene hydroxycinnamates with in vitro antitumor activity from whole cranberry fruit (Vaccinium macrocarpon). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 3541–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denis, M.C.; Desjardins, Y.; Furtos, A.; Marcil, V.; Dudonne, S.; Montoudis, A.; Garofalo, C.; Delvin, E.; Marette, A.; Levy, E. Prevention of oxidative stress, inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction in the intestine by different cranberry phenolic fractions. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2015, 128, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, K.D.; Carlettini, H.; Bouvet, J.; Cote, J.; Doyon, G.; Sylvain, J.F.; Lacroix, M. Effect of different cranberry extracts and juices during cranberry juice processing on the antiproliferative activity against two colon cancer cell lines. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeram, N.P.; Adams, L.S.; Hardy, M.L.; Heber, D. Total cranberry extract versus its phytochemical constituents: Antiproliferative and synergistic effects against human tumor cell lines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 2512–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayansingh, R.; Hurta, R.A.R. Cranberry extract and quercetin modulate the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and IKBA in human colon cancer cells. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2009, 89, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberty, A.M.; Neto, C. Cranberry PACs and triterpenoids: Anti-cancer activities in colon tumor cell lines. Acta Hortic. 2009, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, P.J.; Kurowska, E.M.; Freeman, D.J.; Chambers, A.F.; Koropatnick, J. In vivo inhibition of growth of human tumor lines by flavonoid fractions from cranberry extract. Nutr. Cancer 2006, 56, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kresty, L.A.; Howell, A.B.; Baird, M. Cranberry proanthocyanidins induce apoptosis and inhibit acid-induced proliferation of human esophageal adenocarcinoma cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 676–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weh, K.M.; Aiyer, H.S.; Howell, A.B.; Kresty, L.A. Cranberry proanthocyanidins modulate reactive oxygen species in Barrett’s and esophageal adenocarcinoma cell lines. J. Berry Res. 2016, 6, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresty, L.A.; Weh, K.M.; Zeyzus-Johns, B.; Perez, L.N.; Howell, A.B. Cranberry proanthocyanidins inhibit esophageal adenocarcinoma in vitro and in vivo through pleiotropic cell death induction and PI3K/AKT/mTOR inactivation. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 33438–33455. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weh, K.M.; Howell, A.; Kresty, L.A. Expression, modulation, and clinical correlates of the autophagy protein Beclin-1 in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Mol. Carcinog. 2015, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresty, L.A.; Clarke, J.; Ezell, K.; Exum, A.; Howell, A.B.; Guettouche, T. MicroRNA alterations in Barrett’s esophagus, esophageal adenocarcinoma, and esophageal adenocarcinoma cell lines following cranberry extract treatment: Insights for chemoprevention. J. Carcinog. 2011, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kresty, L.A.; Howell, A.B.; Baird, M. Cranberry proanthocyanidins mediate growth arrest of lung cancer cells through modulation of gene expression and rapid induction of apoptosis. Molecules 2011, 16, 2375–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochman, N.; Houri-Haddad, Y.; Koblinski, J.; Wahl, L.; Roniger, M.; Bar-Sinai, A.; Weiss, E.I.; Hochman, J. Cranberry juice constituents impair lymphoma growth and augment the generation of antilymphoma antibodies in syngeneic mice. Nutr. Cancer 2008, 60, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.P.; Lange, T.S.; Kim, K.K.; Brard, L.; Horan, T.; Moore, R.G.; Vorsa, N.; Singh, R.K. Purified cranberry proanthocyanidines (PAC-1A) cause pro-apoptotic signaling, ROS generation, cyclophosphamide retention and cytotoxicity in high-risk neuroblastoma cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2012, 40, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.P.; Singh, R.K.; Kim, K.K.; Satyan, K.S.; Nussbaum, R.; Torres, M.; Brard, L.; Vorsa, N. Cranberry proanthocyanidins are cytotoxic to human cancer cells and sensitize platinum-resistant ovarian cancer cells to paraplatin. Phytother. Res. 2009, 23, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatelain, K.; Phippen, S.; McCabe, J.; Teeters, C.A.; O’Malley, S.; Kingsley, K. Cranberry and grape seed extracts inhibit the proliferative phenotype of oral squamous cell carcinomas. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babich, H.; Ickow, I.M.; Weisburg, J.H.; Zuckerbraun, H.L.; Schuck, A.G. Cranberry juice extract, a mild prooxidant with cytotoxic properties independent of reactive oxygen species. Phytother. Res. 2012, 26, 1358–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Han, A.; Chen, E.; Singh, R.K.; Chichester, C.O.; Moore, R.G.; Singh, A.P.; Vorsa, N. The cranberry flavonoids PAC DP-9 and quercetin aglycone induce cytotoxicity and cell cycle arrest and increase cisplatin sensitivity in ovarian cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2015, 46, 1924–1934. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.K.; Singh, A.P.; Singh, R.K.; Demartino, A.; Brard, L.; Vorsa, N.; Lange, T.S.; Moore, R.G. Anti-angiogenic activity of cranberry proanthocyanidins and cytotoxic properties in ovarian cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2012, 40, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deziel, B.; MacPhee, J.; Patel, K.; Catalli, A.; Kulka, M.; Neto, C.; Gottschall-Pass, K.; Hurta, R. American cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) extract affects human prostate cancer cell growth via cell cycle arrest by modulating expression of cell cycle regulators. Food Funct. 2012, 3, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLean, M.A.; Scott, B.E.; Deziel, B.A.; Nunnelley, M.C.; Liberty, A.M.; Gottschall-Pass, K.T.; Neto, C.C.; Hurta, R.A. North American cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) stimulates apoptotic pathways in DU145 human prostate cancer cells in vitro. Nutr. Cancer 2011, 63, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deziel, B.A.; Patel, K.; Neto, C.; Gottschall-Pass, K.; Hurta, R.A. Proanthocyanidins from the American cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) inhibit matrix metalloproteinase-2 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 activity in human prostate cancer cells via alterations in multiple cellular signalling pathways. J. Cell Biochem. 2010, 111, 742–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Lin, L.Q.; Song, B.B.; Wang, L.F.; Zhang, C.P.; Zhao, J.L.; Liu, J.R. Cranberry phytochemical extract inhibits SGC-7901 cell growth and human tumor xenografts in Balb/c NU/NU mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodet, C.; Chandad, F.; Grenier, D. Anti-inflammatory activity of a high-molecular-weight cranberry fraction on macrophages stimulated by lipopolysaccharides from periodontopathogens. J. Dent. Res. 2006, 85, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donovan, T.R.; O’Sullivan, G.C.; McKenna, S.L. Induction of autophagy by drug-resistant esophageal cancer cells promotes their survival and recovery following treatment with chemotherapeutics. Autophagy 2011, 7, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osone, S.; Hosoi, H.; Kuwahara, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Iehara, T.; Sugimoto, T. Fenretinide induces sustained-activation of JNK/p38 MAPK and apoptosis in a reactive oxygen species-dependent manner in neuroblastoma cells. Int. J. Cancer 2004, 112, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavanagh, M.E.; O’Sullivan, K.E.; O’Hanlon, C.; O’Sullivan, J.N.; Lysaght, J.; Reynolds, J.V. The esophagitis to adenocarcinoma sequence; the role of inflammation. Cancer Lett. 2014, 345, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhadi, A.; Fields, J.; Banan, A.; Keshavarzian, A. Reactive oxygen species: Are they involved in the pathogenesis of GERD, Barrett’s esophagus, and the latter’s progression toward esophageal cancer? Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2002, 97, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paz, M.F.; Fraga, M.F.; Avila, S.; Guo, M.; Pollan, M.; Herman, J.G.; Esteller, M. A systematic profile of DNA methylation in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 1114–1121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prasad, V.V.T.S.; Gopalan, R.O.G. Continued use of MDA-MB-435, a melanoma cell line, as a model for human breast cancer, even in year, 2014. NPJ Breast Cancer 2015, 1, 15002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbarya, A.; Ruimi, N.; Epelbaum, R.; Ben-Arye, E.; Mahajna, J. Natural products as potential cancer therapy enhancers: A preclinical update. SAGE Open Med. 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HemaIswarya, S.; Doble, M. Potential synergism of natural products in the treatment of cancer. Phytother. Res. 2006, 20, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.P.; Ohnuma, S.; Ambudkar, S.V. Discovering natural product modulators to overcome multidrug resistance in cancer chemotherapy. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2011, 12, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasain, J.K.; Jones, K.; Moore, R.; Barnes, S.; Leahy, M.; Roderick, R.; Juliana, M.M.; Grubbs, C.J. Effect of cranberry juice concentrate on chemically-induced urinary bladder cancers. Oncol. Rep. 2008, 19, 1565–1570. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boateng, J.; Verghese, M.; Shackelford, L.; Walker, L.T.; Khatiwada, J.; Ogutu, S.; Williams, D.S.; Jones, J.; Guyton, M.; Asiamah, D.; et al. Selected fruits reduce azoxymethane (AOM)-induced aberrant crypt foci (ACF) in Fisher 344 male rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007, 45, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X.; Kim, J.; Sun, Q.; Kim, D.; Park, C.S.; Lu, T.S.; Park, Y. Preventive effects of cranberry products on experimental colitis induced by dextran sulphate sodium in mice. Food Chem. 2015, 167, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feliciano, R.P.; Boeres, A.; Massacessi, L.; Istas, G.; Ventura, M.R.; Nunes Dos Santos, C.; Heiss, C.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A. Identification and quantification of novel cranberry-derived plasma and urinary (poly)phenols. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016, 599, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herszenyi, L.; Barabas, L.; Miheller, P.; Tulassay, Z. Colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: The true impact of the risk. Dig. Dis. 2015, 33, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pabla, B.; Bissonnette, M.; Konda, V.J. Colon cancer and the epidermal growth factor receptor: Current treatment paradigms, the importance of diet, and the role of chemoprevention. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 6, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duckworth, C.A.; Burkitt, M.D.; Williams, J.M.; Parsons, B.N.; Tang, J.M.; Pritchard, D.M. Murine models of Helicobacter (pylori or felis)-associated gastric cancer. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 2015, 69, 14.34.1–14.34.35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Iswaldi, I.; Arraez-Roman, D.; Gomez-Caravaca, A.M.; Contreras, M.D.; Uberos, J.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernandez-Gutierrez, A. Identification of polyphenols and their metabolites in human urine after cranberry-syrup consumption. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 55, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohnishi, R.; Ito, H.; Kasajima, N.; Kaneda, M.; Kariyama, R.; Kumon, H.; Hatano, T.; Yoshida, T. Urinary excretion of anthocyanins in humans after cranberry juice ingestion. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2006, 70, 1681–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.J.; Zuo, Y.G.; Vinson, J.A.; Deng, Y.W. Absorption and excretion of cranberry-derived phenolics in humans. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zuo, Y.G. GC-MS determination of flavonoids and phenolic and benzoic acids in human plasma after consumption of cranberry juice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumberg, J.B.; Basu, A.; Krueger, C.G.; Lila, M.A.; Neto, C.C.; Novotny, J.A.; Reed, J.D.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Toner, C.D. Impact of cranberries on gut microbiota and cardiometabolic health: Proceedings of the cranberry health research conference 2015. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 759S–770S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nature 2015, 517, 576–582. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, M.; Tanabe, S.; Howell, A.; Grenier, D. Cranberry proanthocyanidins inhibit the adherence properties of Candida albicans and cytokine secretion by oral epithelial cells. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kresty, L.; Mallery, S.; Stoner, G. Black raspberries in cancer clinical trials: Past, present and future. J. Berry Res. 2016, 6, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anhe, F.F.; Roy, D.; Pilon, G.; Dudonne, S.; Matamoros, S.; Varin, T.V.; Garofalo, C.; Moine, Q.; Desjardins, Y.; Levy, E.; et al. A polyphenol-rich cranberry extract protects from diet-induced obesity, insulin resistance and intestinal inflammation in association with increased Akkermansia spp. Population in the gut microbiota of mice. Gut 2015, 64, 872–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Target | Cell Line(s) | Cranberry Constituent | In Vitro Results [Reference(s)] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | MCF-7 | CE | ↑ apoptosis [23]; ↑ G1 cell cycle arrest [23] |

| ↓ cell viability [23,24] | |||

| CJE | ↓ cell viability [25] | ||

| C-PAC | ↓ cell density [26] | ||

| FG | ↓ cell viability [27] | ||

| Fr6 | ↓ cell viability [28] | ||

| Q | ↓ cell viability [27] | ||

| UA | ↓ cell density [29,30]; ↓ cell viability [27] | ||

| MDA-MB-435* | CJE | ↓ cell viability [25] | |

| Fr6 | ↑ apoptosis [28]; ↑ G2-M cell cycle arrest [28] | ||

| ↓ cell viability [28] | |||

| UA | ↓ cell density [29] | ||

| Cervix | ME180 | C-PAC | ↓ cell density [26] |

| UA | ↓ cell density [30] | ||

| Colon | Caco-2 | CJE | ↓ cell viability [25] |

| TP | ↓ lipid peroxidation [31] | ||

| ↓ pro-inflammatory markers TNFα and IL-6 [31] | |||

| HT-29 | ANTHO | ↓ cell viability [32] | |

| CE | ↓ cell viability [24,33] | ||

| ↓ pro-inflammatory marker COX-2 [34] | |||

| C-PAC | ↑ apoptosis [35]; ↓ cell density [26] | ||

| ↓ cell viability [36] | |||

| CJE | ↓ cell viability [32] | ||

| Fr6 | ↓ cell viability [36] | ||

| TP | ↓ cell viability [32] | ||

| UA | ↑ apoptosis [35]; ↓ cell density [29,30] | ||

| ↓ cell viability [35] | |||

| HCT116 | CE | ↓ cell viability [33] | |

| C-PAC | ↑ apoptosis [35]; ↓ cell viability [35] | ||

| UA | ↑ apoptosis [35]; ↓ cell density [29] | ||

| ↓ cell viability [35] | |||

| LS-513 | ANTHO | ↓ cell viability [32] | |

| CJE | ↓ cell viability [32] | ||

| TP | ↓ cell viability [32] | ||

| SW460 | TP | ↓ cell viability [33] | |

| SW620 | TP | ↓ cell viability [24] | |

| C-PAC | ↓ cell proliferation [37] | ||

| Esophagus | CP-C | C-PAC | ↓ total reactive oxygen species [38] |

| JHEsoAD1 | C-PAC | ↑ autophagy in acid-sensitive cells, pro-death [39,40] | |

| ↑ necrosis in acid-resistant cells [39] | |||

| ↑ G2-M cell cycle arrest [39] | |||

| ↑ total reactive oxygen species [38] | |||

| ↑ hydrogen peroxide levels [38] | |||

| ↓ cell viability [40,41] | |||

| ↓ PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling [39] | |||

| OE33 | C-PAC | ↑ autophagy in acid-sensitive cells [39] | |

| ↑ low levels of apoptosis [39]↑ G2-M cell cycle arrest [39] | |||

| ↓ cell proliferation [39] | |||

| ↑ total reactive oxygen species [38] | |||

| ↓ PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling [39] | |||

| OE19 | C-PAC | ↑ necrosis in acid-resistant cells [39] | |

| ↑ G2-M cell cycle arrest with significant S-phase delay [39] | |||

| ↑ total reactive oxygen species [38] | |||

| ↑ hydrogen peroxide levels [38] | |||

| ↓ PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling [39] | |||

| ↓ cell viability [40,41] | |||

| Glioblastoma | SF295 | UA | ↓ cell density [29] |

| U87 | C-PAC | ↑ apoptosis [36]; ↑ G1 cell cycle arrest [36] | |

| ↓ cell viability [36] | |||

| Fr6 | ↑ apoptosis [36]; ↑ G1 cell cycle arrest [36] | ||

| ↓ cell viability [28] | |||

| Leukemia | K562 | C-PAC | ↓ cell density [26] |

| RPMI8226 | UA | ↓ cell density [29] | |

| Liver | HepG2 | CE | ↑ reduced glutathione levels [22] |

| ↓ glutathione peroxidase activity [22] | |||

| ↓ lipid peroxidation [22] | |||

| ↓ reactive oxygen species [22] | |||

| CJE | ↑ reduced glutathione levels [22] | ||

| ↓ glutathione peroxidase activity [22] | |||

| ↓ lipid peroxidation [22] | |||

| ↓ reactive oxygen species [22] | |||

| FG | ↓ cell viability [27] | ||

| Q | ↓ cell viability [27] | ||

| UA | ↓ cell viability [27] | ||

| Lung | DMS114 | Fr6 | ↓ cell viability [28] |

| NCI-H322M | UA | ↓ cell density [29] | |

| NCI-H460 | C-PAC | ↑ apoptosis [37,42]; ↑ G1 cell cycle arrest [37] | |

| ↓ cell density [26]; ↓ cell viability [37] | |||

| ↓ cell proliferation [37] | |||

| UA | ↓ cell density [29,30] | ||

| Lymphoma | Rev-2-T-6 | NDM | ↓ cell viability [43] |

| ↓ extracellular matrix invasion [43] | |||

| Melanoma | M14 | C-PAC | ↓ cell density [26] |

| UA | ↓ cell density [30] | ||

| SK-MEL5 | Fr6 | ↓ cell viability [28] | |

| Neuroblastoma | IMR-32 | C-PAC | ↓ cell viability [44] |

| SH-Sy5Y | C-PAC | ↓ cell viability [44] | |

| SK-N-SH | C-PAC | ↓ cell viability [44] | |

| SMS-KCNR | C-PAC | ↑ apoptosis [44]; ↑ G2-M cell cycle arrest [44] | |

| ↑ reactive oxygen species [44] | |||

| ↓ PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling [44] | |||

| ↓ cell viability [44,45] | |||

| Oral Cavity | CAL27 | CE | ↑ apoptosis [46]; ↓ cell adhesion [46] |

| ↓ cell density [46]; ↓ cell viability [24] | |||

| TP | ↓ cell viability [33] | ||

| HSC2 | CJE | ↑ reduced glutathione levels [47] | |

| ↓ cell viability [47] | |||

| KB | CE | ↓ cell viability [24] | |

| TP | ↓ cell viability [33] | ||

| SCC25 | CE | ↑ apoptosis [46]; ↓ cell adhesion [46] | |

| ↓ cell density [46] | |||

| Ovary | OVCAR-8 | C-PAC | ↑ G2-M cell cycle arrest [48]; ↓ cell viability [48] |

| SKOV-3 | C-PAC | ↑ apoptosis [48,49]; ↑ G2-M cell cycle arrest [48,49] | |

| ↑ reactive oxygen species [49] | |||

| ↓ AKT signaling [49] | |||

| ↓ cell proliferation [45,49] | |||

| ↓ cell viability [45,48,49] | |||

| Prostate | 22Rv1 | CE | ↓ cell viability [33] |

| TP | ↓ cell viability [33] | ||

| DU-145 | CE | ↑ G1 cell cycle arrest [50] | |

| ↓ cell viability [50,51] | |||

| C-PAC | ↑ apoptosis [51] | ||

| ↑ MAPK signaling [52] | |||

| ↓ cell viability [26,36,51,52] | |||

| ↓ matrix metalloprotease activity [52] | |||

| ↓ PI3K/AKT signaling [52] | |||

| Fr6 | ↓ cell viability [28,36] | ||

| LNCaP | CE | ↓ cell viability [24] | |

| PC3 | CJE | ↑ G1 cell cycle arrest [25] | |

| ↓ cell viability [25] | |||

| C-PAC | ↓ cell density [26] | ||

| UA | ↓ cell density [30] | ||

| RWPE-1 | CE | ↓ cell viability [33] | |

| C-PAC | ↓ cell viability [33] | ||

| TP | ↓ cell viability [33] | ||

| RWPE-2 | CE | ↓ cell viability [33] | |

| C-PAC | ↓ cell viability [33] | ||

| TP | ↓ cell viability [33] | ||

| Renal | RXF393 | UA | ↓ cell density [29] |

| SN12C | UA | ↓ cell density [29] | |

| TK-10 | UA | ↓ cell density [29] | |

| Stomach | AGS | CJE | ↓ cell viability [25] |

| SGC-7901 | CE | ↑ apoptosis [53] | |

| ↓ cell proliferation [53] | |||

| ↓ cell viability [53] |

| Target Organ | In Vivo Models/Cranberry Product and Mode of Delivery/Results |

|---|---|

| [Reference] | |

| Bladder | |

| [65] | Nitrosamine-induced tumors in female F344 rats for eight weeks; following a one-week break, treatment with 0.5 mL/rat or 1.0 mL/rat with cranberry juice concentrate by gavage daily for six months; 31% reduction in bladder tumor weight and 38% reduction in cancerous lesion formation. |

| Colon | |

| [66] | AOM-induced ACF in male F344 rats three weeks after initiation of cranberry juice treament; ad libitum access to 20% cranberry juice in water for 15 weeks; 77% reduction in AOM-induced ACF with reductions in the proximal and distal colon versus untreated controls; significantly increased levels of liver glutathione-S-transferase versus controls. |

| [36] | HT29 (5.0 × 106 cells) xenografts in female NCR NU/NU mice; treatment with cranberry proanthocyanidins (100.0 mg/kg body weight) intraperitoneally three times weekly for 24 days; significant inhibition of explant growth versus controls. |

| [67] | DSS induced experimental colitis in male Balb/c mice at weeks three and six; Treatment with cranberry extract powder (0.1% or 1.0%) or 1.5% freeze dried whole cranberry powder in diet ad libitum from start until ≥ six weeks; cranberry extract powder (1.0%) and 1.5% dried whole cranberry powder treatment normalized stool consistency, decreased blood in fecal samples versus controls and reduced late onset colitis; all treatments decreased serum TNFα levels. |

| Esophagus | |

| [39] | OE19 (1.25 × 106 cells) xenografts in male athymic NU/NU mice; treatment with cranberry proanthocyanidins (250.0 µg/mouse) by oral gavage six days/week for 19 days; 67% decrease in mean tumor volume versus controls and treatment modulated multiple cancer signaling pathways including inactivation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. |

| Glioblastoma | |

| [36] | U87 (1.0 × 106 cells) xenografts in female NCR NU/NU mice; treatment with cranberry proanthocyanidins (100.0 mg/kg body weight) or a flavonoid rich cranberry fraction (250.0 mg/kg body weight) intraperitoneally three times a week; significant inhibition of explant growth by both fractions versus controls |

| Lymphoma | |

| [43] | Rev-2-T-6 (5.0 × 106 cells) xenografts in female Balb/C mice; treatment with non-dialyzable material from cranberry juice concentrate (160.0 mg/kg body weight) intraperitoneally three times a week; significant inhibition of explant growth. |

| Prostate | |

| [36] | DU-145 (4.0 × 106 cells) xenografts in female NCR NU/NU mice; treatment with cranberry proanthocyanidins (100.0 mg/kg body weight) intraperitoneally three times a week; significant inhibition of explant growth by cranberry proanthocyanidin fraction. |

| Stomach | |

| [53] | SGC-7901 (5.0 x 106 cells) xenografts in Balb/c NU/NU mice; SGC-7901 cells were pre-treated with cranberry extract prior to xenograft implantation; increased tumor latency and reduced tumor size in a dose-dependent manner. |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weh, K.M.; Clarke, J.; Kresty, L.A. Cranberries and Cancer: An Update of Preclinical Studies Evaluating the Cancer Inhibitory Potential of Cranberry and Cranberry Derived Constituents. Antioxidants 2016, 5, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox5030027

Weh KM, Clarke J, Kresty LA. Cranberries and Cancer: An Update of Preclinical Studies Evaluating the Cancer Inhibitory Potential of Cranberry and Cranberry Derived Constituents. Antioxidants. 2016; 5(3):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox5030027

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeh, Katherine M., Jennifer Clarke, and Laura A. Kresty. 2016. "Cranberries and Cancer: An Update of Preclinical Studies Evaluating the Cancer Inhibitory Potential of Cranberry and Cranberry Derived Constituents" Antioxidants 5, no. 3: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox5030027

APA StyleWeh, K. M., Clarke, J., & Kresty, L. A. (2016). Cranberries and Cancer: An Update of Preclinical Studies Evaluating the Cancer Inhibitory Potential of Cranberry and Cranberry Derived Constituents. Antioxidants, 5(3), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox5030027