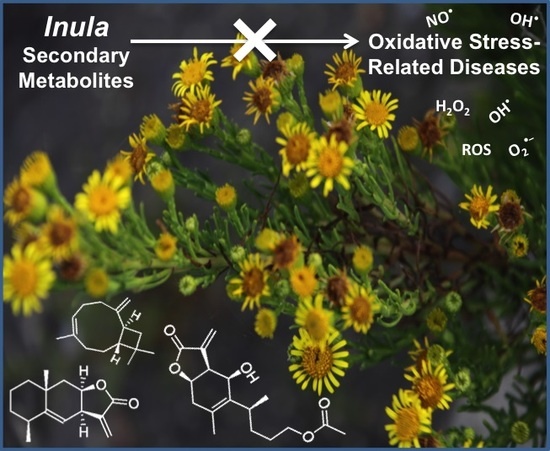

Inula L. Secondary Metabolites against Oxidative Stress-Related Human Diseases

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Radical Scavenging Activity of Secondary Metabolites from Inula Species Determined Using DPPH and ABTS Methods

3. Secondary Metabolites from Inula Species against Oxidative-Stress Related Diseases

3.1. Inflammation

3.2. Diabetes

3.3. Neurological Damages

3.4. Carcinogenesis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3T3-L1 | Mouse adipocytes cells |

| 26-M01 | Murine aggressive colorectal cancer |

| A549 | Human lung carcinoma |

| ABTS | 2,2’-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid |

| AChE | Acetylcholinesterase |

| AD | Alzheimer disease |

| ADR | Adriamycin |

| AML | Acute myeloid leukemia |

| Aβ | Amyloid-β |

| BALB/c | Strain of laboratory mouse |

| Bax | Bcl-2-associated X |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| BV-2 | Mouse microglia cells |

| b.w. | Body weight |

| C57BL/6J | Strain of laboratory mouse |

| CB | Celecoxib |

| CHO | Normal hamster cell line |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase 2 |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DPPH | 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl |

| DPP-IV | Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 |

| FAK | Focal adhesion kinase |

| FLIP | FLICE-inhibitory protein |

| GBM | Glioblastoma multiforme |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide 1 |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GSR | Glutathione reductase |

| GSSG | Glutathione disulphide |

| H460 | Human lung carcinoma |

| H9c2 | Rat cardiomyoblasts |

| HaCaT | Nontumorigenic human epidermal cells |

| HAT | Hydrogen-atom transfer |

| HCT 116 | Human colon cancer |

| HeLa | Human cervical carcinoma |

| HEp-2 | Human larynx epidermal carcinoma |

| HepG2 | Human hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HL-60 | Human acute promyelocytic leukemia |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| HUVEC | Human umbilical vascular endothelial cells |

| IC50 | Half maximal inhibitory concentration |

| IKK | IκB kinase |

| IκB-α | Inhibitory κB-α |

| IL-1 | Interleukin 1 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

| IL-1R | Interleukin-1 receptor |

| IL-4 | Interleukin 4 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| IL-6R | Interleukin 6 receptor |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| JAK | Janus kinase |

| Jurkat | Human acute T cell leukemia |

| K562 | Human bone marrow chronic myelogenous leukemia |

| K562/A02 | Human chronic myelogenous leukemia multidrug-resistant |

| KG1a | Human acute monocytic leukemia |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MCP1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| MDA-MB-231 | Human breast adenocarcinoma |

| MDA-MB-453 | Human breast metastatic carcinoma |

| MDA-MB-468 | Human breast adenocarcinoma (ethnicity: black) |

| MMP | Mitochondrial membrane potential |

| mRNA | Messenger ribonucleic acid |

| NCI-H716 | Human colorectal adenocarcinoma |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-B |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NQO1 | NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase-1 |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| PANC-1 | Human pancreatic epithelioid carcinoma |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| PPARα | Peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor α |

| RAW 264.7 | Macrophage normal cell line |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RNS | Reactive nitrogen species |

| SET | Single-electron transfer |

| SGC-7901 | Gastric carcinoma |

| SH-SY5Y | Human neuroblastoma |

| SI | Selectivity index |

| SMT | 2-methyl-2-thiopseudourea sulphate |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| Src | Steroid receptor coactivator |

| STAT | Signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| SVG | Normal human glial cell |

| TBI | Traumatic brain injury |

| THP-1 | Human acute monocytic leukemia |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor α |

| TNFR | Tumor necrosis factor receptor |

| TRAIL | TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand |

| U87 | Human primary glioblastoma |

| U118 | Human glioblastoma |

| U251 | Human glioblastoma |

| U937 | Human histiocytic lymohoma |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VEGFR2 | Vascular endothelial growth factors receptor-2 |

| XIAP | X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein |

References

- Chandel, N.S.; Budinger, G.R.S. The cellular basis for diverse responses to oxygen. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2007, 42, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymanska, R.; Pospíšil, P.; Kruk, J. Plant-derived antioxidants in disease prevention 2018. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 2018, e2068370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vara, D.; Pula, G. Reactive oxygen species: Physiological roles in the regulation of vascular cells. Curr. Mol. Med. 2014, 14, 1103–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, C.; Mackey, M.M.; Diaz, A.A.; Cox, D.P. Hydroxyl radical is produced via the Fenton reaction in submitochondrial particles under oxidative stress: Implications for diseases associated with iron accumulation. Redox Rep. 2009, 14, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, J.; Xiao, Q.; Zhang, L. Reactive oxygen species: Key regulators in vascular health and diseases. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 1279–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Berndt, C.; Jones, D.P. Oxidative stress. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 715–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaunig, J.E.; Wang, Z. Oxidative stress in carcinogenesis. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2018, 7, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, T.; Biniecka, M.; Veale, D.J.; Fearon, U. Hypoxia, oxidative stress and inflammation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 125, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ighodaro, O.M. Molecular pathways associated with oxidative stress in diabetes mellitus. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 108, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seca, A.M.L.; Pinto, D.C.G.A. Plant secondary metabolites as anticancer agents: Successes in clinical trials and therapeutic application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, G.D. Unlocking the potential of natural products in drug discovery. Microb. Biotechnol. 2019, 12, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seca, A.M.L.; Grigore, A.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Silva, A.M.S. The genus Inula and their metabolites: from ethnopharmacological to medicinal uses. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 154, 286–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seca, A.M.L.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Silva, A.M.S. Metabolomic profile of the genus Inula. Chem. Biodivers. 2015, 12, 859–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Plant List. Available online: http://www.theplantlist.org/1.1/browse/A/Compositae/Inula/ (accessed on 16 February 2019).

- Jeelani, S.M.; Rather, G.A.; Sharma, A.; Lattoo, S.K. In perspective: Potential medicinal plant resources of Kashmir Himalayas, their domestication and cultivation for commercial exploitation. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2018, 8, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamgeer; Uttra, A.M.; Ahsan, H.; Hasan, U.H.; Chaudhary, M.A. Traditional medicines of plant origin used for the treatment of inflammatory disorders in Pakistan: A review. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2018, 38, 636–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.G.; Kang, H. Anti-neuroinflammatory effects of ethanol extract of Inula helenium L (Compositae). Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2016, 15, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Gao, S.; Wu, G.Z.; Yang, N.; Zu, X.P.; Li, W.C.; Xie, N.; Zhang, R.R.; Li, C.W.; Hu, Z.L.; et al. Total sesquiterpene lactones isolated from Inula helenium L. attenuates 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene-induced atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions in mice. Phytomedicine 2018, 46, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, M.J.; Ahn, J.; Jang, Y.J.; Ha, T.Y.; Jung, C.H. Inula japonica Thunb. flower ethanol extract improves obesity and exercise endurance in mice fed a high-fat diet. Nutrients 2019, 11, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.N.; Bristi, N.J.; Rafiquzzaman, M. Review on in vivo and in vitro methods evaluation of antioxidant activity. Saudi Pharm. J. 2013, 21, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedare, S.B.; Singh, R.P. Genesis and development of DPPH method of antioxidant assay. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 48, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszowy, M.; Dawidowicz, A.L. Is it possible to use the DPPH and ABTS methods for reliable estimation of antioxidant power of colored compounds? Chem. Pap. 2018, 72, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badarinath, A.V.; Rao, K.M.; Chetty, C.M.S.; Ramkanth, S.; Rajan, T.V.S.; Gnanaprakash, K. A review of in vitro antioxidant methods: Comparisons, correlations and considerations. Int. J. PharmTech. Res. 2010, 2, 1276–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Nimse, S.B.; Pal, D. Free radicals, natural antioxidants and their reaction mechanisms. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 27986–28006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danino, O.; Gottlieb, H.E.; Grossman, S.; Bergman, M. Antioxidant activity of 1,3-dicaffeoylquinic acid isolated from Inula viscosa. Food Res. Int. 2009, 42, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojakowska, A.; Malarz, J.; Kiss, A.K. Hydroxycinnamates from elecampane (Inula helenium L.) callus culture. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2016, 38, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahham, S.S.; Tabana, Y.M.; Iqbal, M.A.; Ahamed, M.B.K.; Ezzat, M.O.; Majid, A.S.A.; Majid, A.M.S.A. The anticancer, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of the sesquiterpene β-caryophyllene from the essential oil of Aquilaria crassna. Molecules 2015, 20, 11808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priydarshi, R.; Melkani, A.B.; Mohan, L.; Pant, C.C. Terpenoid composition and antibacterial activity of the essential oil from Inula cappa (Buch-Ham. ex. D. Don) DC. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2015, 28, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.J.; Oh, Y.C.; Cho, W.K.; Ma, J.Y. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity determination of one hundred kinds of pure chemical compounds using offline and online screening HPLC assay. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015, 2015, e165457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.M.; Zhang, M.L.; Shi, Q.W. Simultaneous determination of chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, alantolactone and isoalantolactone in Inula helenium by HPLC. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2015, 53, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmieri, M.G.S.; Cruz, L.T.; Bertges, F.S.; Húngaro, H.M.; Batista, L.R.; da Silva, S.S.; Fonseca, M.J.V.; Rodarte, M.P.; Vilela, F.M.P.; do Amaral, M.P.H. Enhancement of antioxidant properties from green coffee as promising ingredient for food and cosmetic industries. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 16, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojakowska, A.; Malarz, J.; Zubek, S.; Turnau, K.; Kisiel, W. Terpenoids and phenolics from Inula ensifolia. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2010, 38, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.J.; Shan, L.; Lu, M.; Shen, Y.H.; Tang, J.; Zhang, W.D. Chemical constituents from Inula cappa. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2010, 46, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, M.; Vlase, L.; Eșianu, S.; Tămaș, M. The analysis of flavonoids from Inula helenium L. flowers and leaves. Acta Med. Marisiensis 2011, 57, 319–323. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, T.; Liu, J.; Chen, D. Comparison of the antioxidant effects of quercitrin and isoquercitrin: Understanding the role of the 6”-OH group. Molecules 2016, 21, e1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, N.J.; Zhao, Y.M.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Li, Y.F. Japonicins A and B from the flowers of Inula japonica. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2006, 8, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rifai, A. Identification and evaluation of in-vitro antioxidant phenolic compounds from the Calendula tripterocarpa Rupr. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 116, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.J.; Jin, H.Z.; Liu, X.H.; Zhang, W.D. Two new sesquiterpenes from Inula salsoloides and their inhibitory activities against NO production. Helv. Chim. Acta 2011, 94, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S.; Islam, M.N.; Ali, M.Y.; Kim, Y.M.; Park, H.J.; Sohn, H.S.; Jung, H.A. The effects of C-glycosylation of luteolin on its antioxidant, anti-Alzheimer’s disease, anti-diabetic, and anti-inflammatory activities. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2014, 37, 1354–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, V.; Trendafilova, A.; Todorova, M.; Danova, K.; Dimitrov, D. Phytochemical profile of Inula britannica from Bulgaria. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12, 153–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.M.; Zhang, D.Q.; Zha, J.P.; Qi, J.L. Simultaneous HPLC determination of five flavonoids in Flos Inulae. Chromatographia 2007, 66, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, S.J.; Kikuchi, D.S.; Hernandes, M.S.; Xu, Q.; Griendling, K.K. Reactive oxygen species in metabolic and inflammatory signaling. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 877–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medzhitov, R. Inflammation 2010: new adventures of an old flame. Cell 2010, 140, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, M.A.; Sousa, L.P.; Pinho, V.; Perretti, M.; Teixeira, M.M. Resolution of inflammation: What controls its onset? Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straub, R.H.; Schradin, C. Chronic inflammatory systemic diseases: An evolutionary trade-off between acutely beneficial but chronically harmful programs. Evol. Med. Public Health 2016, 2016, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 7204–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, J.N.; Al-Omran, A.; Parvathy, S.S. Role of nitric oxide in inflammatory diseases. Inflammopharmacology 2007, 15, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciotti, E.; FitzGerald, G.A. Prostaglandins and inflammation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 986–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goradel, N.H.; Najafi, M.; Salehi, E.; Farhood, B.; Mortezaee, K. Cyclooxygenase-2 in cancer: a review. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 234, 5683–5699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todoric, J.; Antonucci, L.; Karin, M. Targeting inflammation in cancer prevention and therapy. Cancer Prev. Res. 2016, 9, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, G.; Roy, K.; Kumar, G.; Kumari, P.; Alam, S.; Kishore, K.; Panjwani, U.; Ray, K. Distinct influence of COX-1 and COX-2 on neuroinflammatory response and associated cognitive deficits during high altitude hypoxia. Neuropharmacology 2019, 146, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.N.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, E.H.; Lee, M.H.; Kundu, J.K.; Na, H.K.; Cha, Y.N.; Surh, Y.J. Sulforaphane inhibits phorbol ester-stimulated IKK-NF-κB signaling and COX-2 expression in human mammary epithelial cells by targeting NF-κB activating kinase and ERK. Cancer Lett. 2014, 351, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Okuda, J.; Kurazumi, T.; Suhara, T.; Ueda, T.; Nagata, H.; Morisaki, H. Sepsis-induced cardiac dysfunction and β-adrenergic blockade therapy for sepsis. J. Intensive Care 2017, 5, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-H.; Xu, M.; Wu, H.-M.; Wan, C.-X.; Wang, H.-B.; Wu, Q.-Q.; Liao, H.-H.; Deng, W.; Tang, Q.-Z. Isoquercitrin attenuated cardiac dysfunction via AMPKα-dependent pathways in LPS-treated mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, e1800955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.-W.; Qin, J.-J.; Cheng, X.-R.; Shen, Y.-H.; Shan, L.; Jin, H.-Z.; Zhang, W.-D. Inula sesquiterpenoids: structural diversity, cytotoxicity and anti-tumor activity. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2014, 23, 317–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-D.; Qin, J.-J.; Jin, H.-Z.; Yin, Y.-H.; Li, H.-L.; Yang, X.-W.; Li, X.; Shan, L.; Zhang, W.-D. Sesquiterpenoids from Inula racemosa Hook. f. inhibit nitric oxide production. Planta Med. 2012, 78, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.; Choi, R.J.; Khan, S.; Lee, D.-S.; Kim, Y.-C.; Nam, Y.-J.; Lee, D.-U.; Kim, Y.S. Alantolactone suppresses inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 expression by down-regulating NF-κB, MAPK and AP-1 via the MyD88 signaling pathway in LPS-activated RAW 264.7 cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2012, 14, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Han, M.; Sun, R.-H.; Wang, J.-J.; Zhang, Y.-P.; Zhang, D.-Q.; Wen, J.-K. ABL-N-induced apoptosis in human breast cancer cells is partially mediated by c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation. Breast Cancer Res. 2010, 12, R9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.-M.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y.-B.; Wang, J.-J.; Wen, J.-K.; Li, B.-H.; Han, M. Acetylbritannilactone suppresses growth via upregulation of krüppel-like transcription factor 4 expression in HT-29 colorectal cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2011, 26, 1181–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.L.; Hussain, J.; Hamayun, M.; Gilani, S.A.; Ahmad, S.; Rehman, G.; Kim, Y.-H.; Kang, S.-M.; Lee, I.-J. Secondary metabolites from Inula britannica L. and their biological activities. Molecules 2010, 15, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Wen, J.K.; Li, B.H.; Fang, X.M.; Wang, J.J.; Zhang, Y.P.; Shi, C.J.; Zhang, D.Q.; Han, M. Celecoxib and acetylbritannilactone interact synergistically to suppress breast cancer cell growth via COX-2-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Cell Death Dis. 2011, 2, e185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.-P.; Chen, Y.-F.; Zhu, H.; Wu, X.-R.; Yu, Y.; Kong, D.-X.; Duan, H.-Q.; Jin, M.-H.; Qin, N. Synthesis and anti-inflammatory activities of 1-O-acetylbritannilactone analogues. Phytochem. Lett. 2017, 19, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garayev, E.; Di Giorgio, C.; Herbette, G.; Mabrouki, F.; Chiffolleau, P.; Roux, D.; Sallanon, H.; Ollivier, E.; Elias, R.; Baghdikian, B. Bioassay-guided isolation and UHPLC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS quantification of potential anti-inflammatory phenolic compounds from flowers of Inula montana L. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 226, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Lee, J.W.; Jang, H.; Lee, H.L.; Kim, J.G.; Wu, W.; Lee, D.; Kim, E.-H.; Kim, Y.; Hong, J.T.; Lee, M.K.; Hwang, B.Y. Dimeric- and trimeric sesquiterpenes from the flower of Inula japonica. Phytochemistry 2018, 155, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharroubi, A.T.; Darwish, H.M. Diabetes mellitus: The epidemic of the century. World J. Diabetes 2015, 6, 850–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, C.M.O.; Villar-Delfino, P.H.; dos Anjos, P.M.F.; Nogueira-Machado, J.A. Cellular death, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and diabetic complications. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnert, K.-D.; Freyse, E.-J.; Salzsieder, E. Glycaemic variability and pancreatic β-cell dysfunction. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2012, 8, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Sears, D.D. TLR4 and insulin resistance. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2010, 2010, 212563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Chen, R.; Wang, H.; Liang, F. Mechanisms linking inflammation to insulin resistance. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 2015, 508409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.H.; Choi, S.E.; Ha, E.S.; Jung, J.G.; Han, S.J.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.J.; Kang, Y.; Lee, K.W. IL-6 induction of TLR-4 gene expression via STAT3 has an effect on insulin resistance in human skeletal muscle. Acta Diabetol. 2013, 50, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuñiga, L.Y.; Aceves-de la Mora, M.C.; González-Ortiz, M.; Ramos-Núñez, J.L.; Martínez-Abundis, E. Effect of chlorogenic acid administration on glycemic control, insulin secretion, and insulin sensitivity in patients with impaired glucose tolerance. J. Med. Food 2018, 21, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, S.M.H.; Sun, R.-Q.; Zeng, X.-Y.; Choong, Z.-H.; Wang, H.; Watt, M.J.; Ye, J.-M. Activation of PPARα ameliorates hepatic insulin resistance and steatosis in high fructose-fed mice despite increased endoplasmic reticulum stress. Diabetes 2013, 62, 2095–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Yan, Z.; Zhong, J.; Chen, J.; Ni, Y.; Li, L.; Ma, L.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhu, Z. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 activation enhances gut glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion and improves glucose homeostasis. Diabetes 2012, 61, 2155–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, C.F.; Mannucci, E.; Ahrén, B. Glycaemic efficacy of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors as add-on therapy to metformin in subjects with type 2 diabetes-a review and meta analysis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2012, 14, 762–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.-T.; Yin, Y.-C.; Xing, S.; Li, W.-N.; Fu, X.-Q. Hypoglycemic effect and mechanism of isoquercitrin as an inhibitor of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 in type 2 diabetic mice. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 14967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.-L.; He, Y.; Ji, L.-L.; Wang, K.-Y.; Wang, Y.-L.; Chen, D.-F.; Geng, Y.; OuYang, P.; Lai, W.-M. Hepatoprotective potential of isoquercitrin against type 2 diabetes-induced hepatic injury in rats. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 101545–101559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Song, K.; Kim, Y.S. Alantolactone improves prolonged exposure of interleukin-6-induced skeletal muscle inflammation associated glucose intolerance and insulin resistance. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gu, B.J.; Masters, C.L.; Wang, Y.-J. A systemic view of Alzheimer disease - insights from amyloid-β metabolism beyond the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 13, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, R.K.; Beal, M.F. Mitochondrial diseases of the brain. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 63, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, S.; Guillemin, G.J.; Abiramasundari, R.S.; Essa, M.M.; Akbar, M.; Akbar, M.D. The role of reactive oxygen species in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease: a mini review. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, e8590578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.Y.; Lim, S.S.; Kim, J.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, J.-S. Alantolactone and isoalantolactone prevent amyloid β25-35-induced toxicity in mouse cortical neurons and scopolamine-induced cognitive impairment in mice. Phytother. Res. 2017, 31, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q. Role of Nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 53, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; An, C.; Gao, Y.; Leak, R.K.; Chen, J.; Zhang, F. Emerging roles of Nrf2 and phase II antioxidant enzymes in neuroprotection. Prog. Neurobiol. 2013, 100, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-G.; Laird, M.D.; Han, D.; Nguyen, K.; Scott, E.; Dong, Y.; Dhandapani, K.M.; Brann, D.W. Critical role of NADPH oxidase in neuronal oxidative damage and microglia activation following traumatic brain injury. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lan, Y.-L.; Xing, J.-S.; Lan, X.-Q.; Wang, L.-T.; Zhang, B. Alantolactone plays neuroprotective roles in traumatic brain injury in rats via anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative and anti-apoptosis pathways. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2018, 10, 368–380. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.-S.; Xie, K.-Q.; Zhang, C.-L.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Zhang, L.-P.; Guo, X.; Yu, S.-F. Allyl chloride-induced time dependent changes of lipid peroxidation in rat nerve tissue. Neurochem. Res. 2005, 30, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ighodaro, O.M.; Akinloye, O.A. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): Their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alexandria J. Med. 2018, 54, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M.T.; Carson, M.J.; El Khoury, J.; Landreth, G.E.; Brosseron, F.; Feinstein, D.L.; Jacobs, A.H.; Wyss-Coray, T.; Vitorica, J.; Ransohoff, R.M.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadfar, S.; Hwang, C.J.; Lim, M.-S.; Choi, D.-Y.; Hong, J.T. Involvement of inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis and therapeutic potential of anti-inflammatory agents. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2015, 38, 2106–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Dong, B.; Yang, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jin, D.-Q.; Ohizumi, Y.; Lee, D.; Xu, J.; Guo, Y. NO inhibitors function as potential anti-neuroinflammatory agents for AD from the flowers of Inula japonica. Bioorg. Chem. 2018, 77, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, M.; Hayes, A.; Caprnda, M.; Petrovic, D.; Rodrigo, L.; Kruzliak, P.; Zulli, A. Inducible nitric oxide synthase: Good or bad? Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 93, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Shimizu, M.; Kochi, T.; Moriwaki, H. Chemical-induced carcinogenesis. J. Exp. Clin. Med. 2013, 5, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Badana, A.K.; Gavara, M.M.; Gugalavath, S.; Malla, R. Reactive oxygen species: A key constituent in cancer survival. Biomark. Insights 2018, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Bae, J.-S. ROS homeostasis and metabolism: a critical liaison for cancer therapy. Exp. Mol. Med. 2016, 48, e269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tafani, M.; Sansone, L.; Limana, F.; Arcangeli, T.; De Santis, E.; Polese, M.; Fini, M.; Russo, M.A. The interplay of reactive oxygen species, hypoxia, inflammation, and sirtuins in cancer initiation and progression. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016, 2016, e3907147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yu, Z.; Wang, C.; Cheng, W.; Tian, X.; Huo, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, C.; Feng, L.; Xing, J.; et al. Alantolactone, a natural sesquiterpene lactone, has potent antitumor activity against glioblastoma by targeting IKKβ kinase activity and interrupting NF-κB/COX-2-mediated signaling cascades. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 36, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Gao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Vasdev, N.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q. Alantolactone selectively ablates acute myeloid leukemia stem and progenitor cells. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 9, e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, H.; Qiao, J.-O. 1-O-Acetylbritannilactone combined with gemcitabine elicits growth inhibition and apoptosis in A549 human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 5568–5572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajabi, M.; Mousa, S.A. The role of angiogenesis in cancer treatment. Biomedicines 2017, 5, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albini, A.; Tosetti, F.; Li, V.W.; Noonan, D.M.; Li, W.W. Cancer prevention by targeting angiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 9, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sennino, B.; McDonald, D.M. Controlling escape from angiogenesis inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cébe-Suarez, S.; Zehnder-Fjällman, A.; Ballmer-Hofer, K. The role of VEGF receptors in angiogenesis; complex partnerships. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006, 63, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanella, C.; Ongaro, E.; Bolzonello, S.; Guardascione, M.; Fasola, G.; Aprile, G. Clinical advances in the development of novel VEGFR2 inhibitors. Ann. Transl. Med. 2014, 2, e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, C.; Simiantonaki, N.; Habedank, S.; Kirkpatrick, C.J. The relevance of cell type- and tumor zone-specific VEGFR-2 activation in locally advanced colon cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 34, e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-R.; Cai, Q.-Y.; Gao, Y.-G.; Luan, X.; Guan, Y.-Y.; Lu, Q.; Sun, P.; Zhao, M.; Fang, C. Alantolactone, a sesquiterpene lactone, inhibits breast cancer growth by antiangiogenic activity via blocking VEGFR2 signaling. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhengfu, H.; Hu, Z.; Huiwen, M.; Zhijun, L.; Jiaojie, Z.; Xiaoyi, Y.; Xiujun, C. 1-o-acetylbritannilactone (ABL) inhibits angiogenesis and lung cancer cell growth through regulating VEGF-Src-FAK signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 464, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Pan, W.; Xu, J.; Wang, T.; Chen, T.; Liu, Z.; Xie, C.; Zhang, Q. Sesquiterpenoids from the roots of Inula helenium inhibit acute myelogenous leukemia progenitor cells. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 86, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindler, C.; Levy, D.E.; Decker, T. JAK-STAT signaling: from interferons to cytokines. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 20059–20063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoops, L.; Hornakova, T.; Royer, Y.; Constantinescu, S.N.; Renauld, J.-C. JAK kinases overexpression promotes in vitro cell transformation. Oncogene. 2008, 27, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Niu, G.; Kortylewski, M.; Burdelya, L.; Shain, K.; Zhang, S.; Bhattacharya, R.; Gabrilovich, D.; Heller, R.; Coppola, D.; Dalton, W.; Jove, R.; Pardoll, D.; Yu, H. Regulation of the innate and adaptive immune responses by Stat-3 signaling in tumor cells. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, R.L.; Pardanani, A.; Tefferi, A.; Gilliland, D.G. Role of JAK2 in the pathogenesis and therapy of myeloproliferative disorders. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007, 7, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.-H.; Kuang, S.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.-X.; Gu, Y.; Hu, L.-H.; Yu, Q. Bigelovin inhibits STAT3 signaling by inactivating JAK2 and induces apoptosis in human cancer cells. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2015, 36, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, G.-Z.; Tan, N.-H.; Ji, C.-J.; Fan, J.-T.; Huang, H.-Q.; Han, H.-J.; Zhou, G.-B. Apoptosis inducement of bigelovin from Inula helianthus-aquatica on human leukemia U937 cells. Phytother. Res. 2009, 23, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Yue, G.G.-L.; Song, L.-H.; Huang, M.-B.; Lee, J.K.-M.; Tsui, S.K.-W.; Fung, K.-P.; Tan, N.-H.; Lau, C.B.-S. Natural small molecule bigelovin suppresses orthotopic colorectal tumor growth and inhibits colorectal cancer metastasis via IL6/STAT3 pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 150, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.; Tang, J.-J.; Zhang, C.-C.; Tian, J.-M.; Guo, J.-T.; Zhang, Q.; Li, H.; Gao, J.-M. Semisynthesis and in vitro cytotoxic evaluation of new analogues of 1-O-acetylbritannilactone, a sesquiterpene from Inula britannica. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 80, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.-J.; Dong, S.; Han, Y.-Y.; Lei, M.; Gao, J.-M. Synthesis of 1-O-acetylbritannilactone analogues from Inula britannica and in vitro evaluation of their anticancer potential. Med. Chem. Commun. 2014, 5, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, M.E. Design and synthesis of analogues of natural products. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 5302–5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaunig, J.E.; Wang, Z.; Pu, X.; Zhou, S. Oxidative stress and oxidative damage in chemical carcinogenesis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2011, 254, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, Y.; Cao, F.; Li, M.; Li, P.; Xu, T.; Wang, X.; Yu, Y.; Gu, B.; Yu, X.; Cai, X.; et al. Enhanced mitochondrial pyruvate transport elicits a robust ROS production to sensitize the antitumor efficacy of interferon-γ in colon cancer. Redox Biol. 2019, 20, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Bu, W.; Song, J.; Feng, L.; Xu, T.; Liu, D.; Ding, W.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Ma, B.; et al. Apoptosis induction by alantolactone in breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells through reactive oxygen species-mediated mitochondrion-dependent pathway. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2018, 41, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Song, L.H.; Yue, G.G.L.; Lee, J.K.M.; Zhao, L.M.; Li, L.; Zhou, X.; Tsui, S.K.W.; Ng, S.S.-M.; Fung, K.-P.; et al. Bigelovin triggered apoptosis in colorectal cancer in vitro and in vivo via upregulating death receptor 5 and reactive oxidative species. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, J. Alantolactone induces apoptosis of human cervical cancer cells via reactive oxygen species generation, glutathione depletion and inhibition of the Bcl-2/Bax signaling pathway. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 11, 4203–4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Duan, D.; Yao, J.; Gao, K.; Fang, J. Inhibition of thioredoxin reductase by alantolactone prompts oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis of HeLa cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016, 102, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | DPPH (Reference Compound) | ABTS (Reference Compound) | Inula Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1,3-dicaffeoylquinic acid (1) | 12 ± 0.4 (Ascorbic acid: 15 ± 0.01) [25] | Inula helenium [26] | |

| β-caryophyllene (2) | 1.25 ± 0.06 (Ascorbic acid: 1.5 ± 0.03) [27] | Inula cappa (Buch.-Ham. ex D.Don) DC. * [28] | |

| Caffeic acid (3) | 25.0 ± 1.7 (Ascorbic acid: 20.7 ± 1.31) ** [29] | 8.82 ± 0.33 (Ascorbic acid: 15.05 ± 2.61) ** [29] | Inula helenium [30] |

| Chlorogenic acid (4) | 36.83 ± 0.76 (Caffeic acid: 35.02 ± 2.11) ** [31] | Inula ensifolia L. [32], Inula cappa [33], Inula helenium [34] | |

| Isoquercitrin (5) | 12.68 ± 0.54 (Trolox: 18.10 ± 0.44) ** [35] | Inula japonica [36], Inula ensifolia [32], Inula helenium [34] | |

| Kaempferol (6) | 27.18 ± 1.05 (Ascorbic acid: 20.72 ± 1.31) ** [29] 47.97 ± 0.03 (Ascorbic acid: 20.27 ± 0.11) ** [37] | 12.93 ± 0.52 (Ascorbic acid: 15.05 ± 2.61) ** [29] | Inula salsoloides (Turcz.) Ostenf. [38] |

| Luteolin (7) | 6.69 ± 0.15 (Ascorbic acid: 16.88 ± 0.02) [39] | Inula japonica [36], Inula salsoloides [38], Inula britannica L. [40] | |

| Quercetin (8) | 8.80 ± 0.79 (Ascorbic acid: 20.72 ± 1.31) ** [29] 19.75 ± 1.06 (Caffeic acid: 35.02 ± 2.11) ** [31] | 6.25 ± 1.09 (Ascorbic acid: 15.05 ± 2.61) ** [29]* | Inula japonica [36], Inula britannica [41], Inula helenium [34] |

| Quercitrin (9) | 9.93 ± 0.38 (Trolox: 18.10 ± 0.44) [35] | Inula japonica [36], Inula ensifolia [32], Inula helenium [34] | |

| Rutin (10) | 19.31 ± 0.39 (Caffeic acid: 35.02 ± 2.11) ** [31] | Inula helenium [34] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tavares, W.R.; Seca, A.M.L. Inula L. Secondary Metabolites against Oxidative Stress-Related Human Diseases. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox8050122

Tavares WR, Seca AML. Inula L. Secondary Metabolites against Oxidative Stress-Related Human Diseases. Antioxidants. 2019; 8(5):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox8050122

Chicago/Turabian StyleTavares, Wilson R., and Ana M. L. Seca. 2019. "Inula L. Secondary Metabolites against Oxidative Stress-Related Human Diseases" Antioxidants 8, no. 5: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox8050122