Clinical and Molecular-Genetic Insights into the Role of Oxidative Stress in Diabetic Retinopathy: Antioxidant Strategies and Future Avenues

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

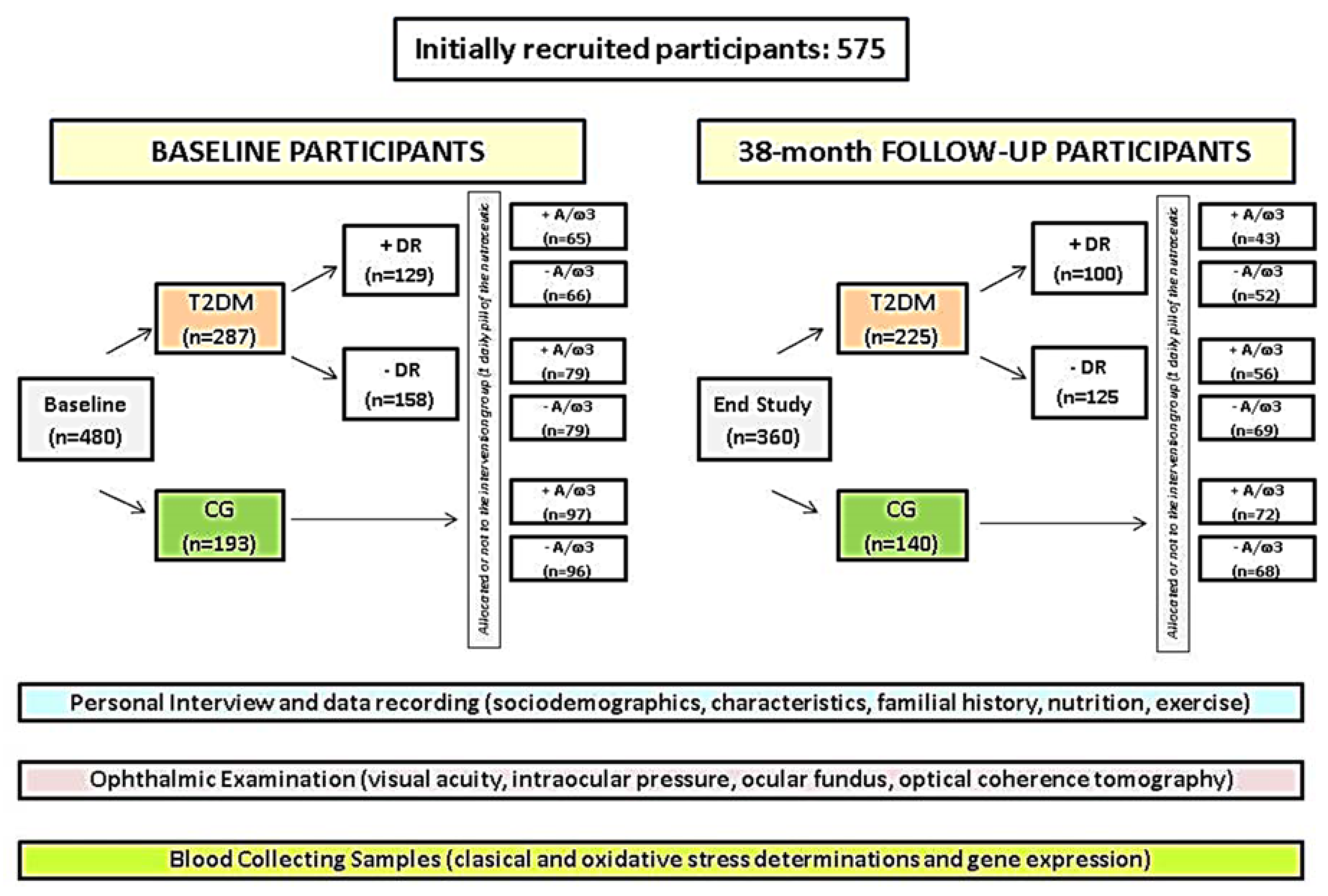

2.1. Community-Based Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Screening Procedures

2.3.1. Selection and Appointment Schedules

2.3.2. Ophthalmologic Procedures

2.3.3. Biosample Processing

- -Determination of lipid peroxidation by-products. MDA/thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS): MDA/TBARS. It was assayed at high temperature (90–100 °C) under acidic conditions and extracted with butanol. Fluorescence was measured in duplicate at 544 nm excitation, 590 nm emission in relation to standard samples fluorescence. The concentration was calculated by extrapolating all data in the standard curve, as reported [19,29].

- -Determination of TAC. This was measured by the antioxidant assay kit (Ref: 709001, Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) based on the antioxidant capacity to inhibit the 2,2′-azino-di-[3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulphonate] oxidation to 2,2′-azino-di-[3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulphonate] radical solution by the metmyoglobin, as published [19,30].

- -Determination of total GSH. A modification was done [19] of the method, firstly reported by Tietze [31]. The OxiSelectTM Total GSH (GSSG/GSH) kit was utilized (Cell Biolabs, INC, Ref: STA-312. Madrid, Spain). Global thiol reagent, 5-5′-dithiobis [2-nitrobenzoic acid] (DTNB) reacts with GSH to form both the 412 nm chromophore, 5-thionitrobenzoic acid (TNB), and the disulfide product (GS-TNB). The GS-TNB was reduced through an enzymatic reaction catalyzed by the GSH reductase and β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). Thus, a second TNB molecule was released by recycling the GSH. Any oxidized GSH (GSSG) initially presented in the reaction mixture or formed from the mixed disulfide reaction of GSH with GS-TNB is reduced to GSH, and measured, as described [19,31].

- -Determination of the glycemic profile [fasting glucose and HbA1c were performed by 2 different automated chemistry analyzers in the Department of Clinical Analysis of the main study center, as follows: (1) Abbott kits manufactured for use with the Architect c8000 (Abbott Laboratories; Abbott Park, IL, USA) and (2) Arkray AU 4050 (Arkray Global Bunisess Inc., Kyoto, Japan), respectively.

- -Determination of plasma vitamin C (vit C). Fresh frozen plasma aliquots were thawed and acidified by adding perchloric acid and diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA; a strong trace metal chelator) for avoiding the ascorbate to destabilize. After centrifugation, supernatants were treated with Tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP; a potent thiol-free reducing agent) to gather any rest of the ascorbate that became oxidized during previous proceedings. The concentration of vit C was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with electrochemical detection, as previously reported [32,33]. Briefly, a Shimadzu HPLC System (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Columbia, MD, USA) that was equipped with a 5 µM YMCPack ODS-AQ column (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA) and a Coulochem III electrochemical detector (ESA, Chelmsford, MA, USA), under reversed-phase conditions was used. Sampling injection volume was 5 µL, and compounds were eluted over an 18 min runtime at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min, following the method described by Li [32] with minor modifications [33]. Plasma vit C concentrations were expressed as mean (SD) in µmol/mL, taking into consideration the Linus Pauling Institute recommendations (https://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/vitamins/vitamin-C) of consuming sufficient vit C to obtain at least a circulating concentration of 60 μmol/L, as well as international guidelines as follows: <11 μmol/L indicate severe deficiency; 23–50 μmol/L inadequate; 50–70 μmol/L adequate; and >70 μmol/L is deemed saturating.

- -Gene expression assays. Whole blood samples were obtained from each participant and collected into EDTA tubes. Total RNA was isolated from blood samples by the Trizol method. Then, 300 ng of total RNA (integrity number—RIN > 7) were converted into cDNA by reverse transcription using the High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA™ Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The relative SLC23A2 gene expression was analyzed by real-time PCR, using a 7900HT Sequence Detection System (SDS; Applied Biosystems®, Madrid, Spain). TaqMan gene expression assays were used for both target (SLC23A2) and internal control (18S rRNA) genes (Applied Biosystems®, Spain). Samples were assayed in duplicate. The expression values were calculated by the double delta Ct formula, as previously reported [34,35], and the results were expressed as fold changes in gene expression for each group and subgroup, at baseline.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| +/− A/ω3 | plus/without a pill of nutraceutical supplement per day |

| +/− DR | with/without diabetic retinopathy |

| A | Antioxidants |

| BCVA | best corrected visual acuity |

| BMI | body mass index |

| CG | healthy control group |

| DHA | docosahexaenoic acid |

| DM | diabetes mellitus |

| DME | diabetic macular edema |

| EDTA | ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid |

| GSH | glutathione |

| GSSG | oxidized GSH |

| HbA1c | glycosylated haemoglobin |

| HPLC | high performance liquid chromatography |

| IOP | intraocular pressure |

| MedDiet | Mediterranean diet |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| NPDR | non proliferative diabetic retinopathy |

| OCT | optical coherence tomography |

| OS | oxidative stress |

| PDR | proliferative diabetic retinopathy |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SD-OCT | spectral domain optical coherence tomography |

| SLC23A2 | solute carrier family 23 member 2 |

| T1DM | type 1 diabetes mellitus |

| T2DM | type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| TAC | total antioxidant capacity |

| TBARS | thiobarbituric acid reactive substances |

| TNB | 5-thionitrobenzoic acid |

| Vit | Vitamin |

| ω3 | omega 3 fatty acids |

References

- Wu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Zhang, W. Risk factors contributing to type 2 diabetes and recent advances in the treatment and prevention. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 11, 1185–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chawla, R.; Madhu, S.V.; Makkar, B.M.; Ghosh, S.; Saboo, B.; Kalra, S. On behalf of RSSDI-ESI Consensus Group RSSDI-ESI clinical practice recommendations for the management of Type 2 diabetes mellitus 2020. Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries 2020, 40 (Suppl. S1–S122), 1–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Ma, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, L.; Mo, Y.; Ying, L.; Lu, W.; Zhu, W.; Bao, Y.; Vigersky, R.A.; et al. Association of Time in Range, as Assessed by Continuous Glucose Monitoring, With Diabetic Retinopathy in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 2370–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simó, R.; Hernández, C. Novel approaches for treating diabetic retinopathy based on recent pathogenic evidence. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2015, 48, 160–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammes, H.P.; Welp, R.; Kempe, H.P.; Wagner, C.; Siegel, E.; Holl, R.W. DPV initiative—German BMBF competence network diabetes mellitus. Risk factors for retinopathy and diabetic macular edema in Type 2 diabetes-results from the German/Austrian DPV Database. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Zhang, D.; Ren, Q.; Su, X.; Sun, Z. Prevalence and risk factors of diabetic retinopathy in diabetic patients: A community based cross-sectional study. Medicine 2020, 99, e19236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerschman, R.; Gilbert, D.; Nye, S.W.; Dwyer, P.; Fenn, W.O. Oxygen poisoning and x-irradiation: A mechanism in common. Science 1954, 19, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Imlay, J.A. Redox pioneer: Professor Irwin Fridovich. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 14, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ignarro, L.J. Endothelium-derived nitric oxide: Pharmacology and relationship to the actions of organic esters. Pharm. Res. 1989, 6, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncada, S.; Palmer, R.M.; Higgs, E.A. Nitric oxide: Physiology, pathophysiology and pharmacology. Pharmacol. Rev. 1991, 43, 109–142. [Google Scholar]

- Hempel, N.; Melendez, J.A. Intracellular redox status controls membrane localization of pro- and anti-migratory signaling molecules. Redox Biol. 2014, 2, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Doly, M.; Droy-Lefaix, M.T.; Braquet, P. Oxidative stress in diabetic retina. EXS 1992, 62, 299–307. [Google Scholar]

- Verdejo, C.; Marco, P.; Renau-Piqueras, J.; Pinazo-Duran, M.D. Lipid peroxidation in proliferative vitreoretinopathies. Eye 1999, 13, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madsen-Bouterse, S.A.; Kowluru, R.A. Oxidative stress and diabetic retinopathy: Pathophysiological mechanisms and treatment perspectives. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2008, 9, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Deng, A.; Liu, J.; Hou, W. The role of Keap1-Nrf2-ARE signal pathway in diabetic retinopathy oxidative stress and related mechanisms. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2018, 11, 3084–3090. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J.B.; Coates, P.M.; Russell, R.M.; Dwyer, J.T.; Schuttinga, J.A.; Bowman, B.A. Economic analysis of nutrition interventions for chronic disease prevention: Methods. Res. Pol. Nutr. Rev. 2011, 69, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, D.; Leahy, M.M.; Milner, J.A.; Allison, D.B.; Dodd, K.W.; Gaine, P.C. Strategies to optimize the impact of nutritional surveys and epidemiological studies. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kowluru, R.A.; Zhong, Q.; Santos, J.M.; Thandampallayam, M.; Putt, D.; Gierhart, D.L. Beneficial effects of the nutritional supplements on the development of diabetic retinopathy. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roig-Revert, M.J.; Lleó-Pérez, A.; Zanón-Moreno, V.; Vivar-Llopis, B.; Marín-Montiel, J.; Dolz-Marco, R.; Alonso-Muñoz, L.; Albert-Fort, M.; López-Gálvez, M.I.; Galarreta-Mira, D.; et al. Enhanced oxidative stress and other potential biomarkers for retinopathy in Type 2 diabetics: Beneficial effects of the nutraceutic supplements. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 408180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, J.; Puranik, S.; Yadav, R.; Manwaring, H.R.; Pierre, S.; Srivastava, R.K.; Yadav, R.S. Dietary interventions for Type 2 diabetes: How millet comes to help. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala-Vila, A.; Díaz-López, A.; Valls-Pedret, C.; Cofán, M.; García-Layana, A.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; Castañer, O.; Zanon-Moreno, V.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Toledo, E.; et al. Dietary marine ω-3 fatty acids and incident sight-threatening retinopathy in middle-aged and older individuals with Type 2 diabetes: ProspectiveInvestigation from the PREDIMED trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016, 134, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelam, K.; Goenadi, C.J.; Lun, K.; Yip, C.C.; Eong, K.G.A. Putative protective role of lutein and zeaxanthin in diabetic retinopathy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 101, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njike, V.Y.; Annam, R.; Costales, V.C.; Yarandi, N.; Katz, D.L. Which foods are displaced in the diets of adults with type 2 diabetes with the inclusion of eggs in their diets? A randomized, controlled, crossover trial. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2017, 5, e000411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boadi-Kusi, S.B.; Asiamah, E.; Ocansey, S.; Abu, S.L. Nutrition knowledge and dietary patterns in ophthalmic patients. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhr, D.; Halfter, H.; Schulz, J.B.; Young, P.; Gess, B. Sodium-dependent Vitamin C transporter 2 deficiency impairs myelination and remyelination after injury: Roles of collagen and demethylation. Glia 2017, 65, 1186–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Rahmani, A.H.; Aldebasi, Y.H. Diabetic retinopathy: Recent updates on different biomarkers and some therapeutic agents. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2018, 14, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Qiao, S.; Shi, C.; Wang, S.; Ji, G. Metabolomics window into diabetic complications. J. Diabetes Investig. 2018, 9, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Grading diabetic retinopathy from stereosopic color fundus photographs—An extension of the modified Airlie House classification. ETDRS report number 10. Ophthalmology 1991, 98 (Suppl. 5), 786–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama, M.; Mihara, M. Determination of malondialdehyde precursor in tissues by thiobarbituric acid test. Anal. Biochem. 1978, 86, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambayashi, Y.; Binh, N.T.; Asakura, H.W.; Hibino, Y.; Hitomi, Y.; Nakamura, H. Efficient assay for total antioxidant capacity in human plasma using a 96-well microplate. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2009, 44, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teitze, F. Enzymatic method for the quantitative determination of nanogram amounts of total and oxidized glutathione: Applications to mammalian blood and other tissues. Anal. Biochem. 1969, 27, 502–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Franke, A.A. Fast HPLC–ECD analysis of ascorbic acid, dehydroascorbic acid and uric acid. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life. Sci. 2009, 877, 853–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanon-Moreno, V.; Ciancotti-Olivares, L.; Asencio, J.; Sanz, P.; Ortega-Azorin, C.; Pinazo-Duran, M.D.; Corella, D. Association between a SLC23A2 gene variation, plasma vitamin C levels, and risk of glaucoma in a Mediterranean population. Mol. Vis. 2011, 17, 2997–3004. [Google Scholar]

- Pinazo-Durán, M.D.; Zanón-Moreno, V.; Lleó-Perez, A.; García-Medina, J.J.; Galbis-Estrada, C.; Roig-Revert, M.J.; Marco-Ramírez, C.; López-Gálvez, M.; Dolz-Marco, R.; Duarte, L.; et al. Genetic systems for a new approach to risk of progression of diabetic retinopathy. Arch. Soc. Esp. Oftalmol. 2016, 91, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinazo-Durán, M.D.; Shoaie-Nia, K.; Sanz-González, S.M.; Raga-Cervera, J.; García-Medina, J.J.; López-Gálvez, M.I.; Galarreta-Mira, D.; Duarte, L.; Campos-Borges, C.; Zanon-Moreno, V.; et al. Identification of new candidate genes for retinopathy in type 2 diabetics. Valencia Study on Diabetic Retinopathy (VSDR). Report number 3. Arch. Soc. Esp. Oftalmol. 2018, 93, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Aroca, P.; de la Riva-Fernandez, S.; Valls-Mateu, A.; Sagarra-Alamo, R.; Moreno-Ribas, A.; Soler, N. Changes observed in diabetic retinopathy: Eight-year follow-up of a Spanish population. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 100, 1366–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zeng, Y.; Cao, D.; Yu, H.; Yang, D.; Zhuang, X.; Hu, Y. Early retinal neurovascular impairment in patients with diabetes without clinically detectable retinopathy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 103, 1747–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, F.; Chen, Q.; Ahuang, X.; Wu, C.; Qian, Y.; Wang, Y. Associated risk factors in the early stage of diabetic retinopathy. Eye Vis. 2019, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancino, R.; di Pierro, D.; Varesi, C.; Cerulli, A.; Feraco, A.; Cedrone, C.; Pinazo-Duran, M.D. Lipid peroxidation and total antioxidant capacity in vitreous, aqueous humor, and blood samples from patients with diabetic retinopathy. Mol. Vis. 2011, 17, 1298–1304. [Google Scholar]

- Pinazo-Durán, M.D.; Gallego-Pinazo, R.; García-Medina, J.J.; Zanón-Moreno, V.; Nucci, C.; Dolz-Marco, R.; Martínez-Castillo, S.; Galbis-Estrada, C.; Marco-Ramírez, C.; López-Gálvez, M.I.; et al. Oxidative stress and its downstream signaling in aging eyes. Clin. Interv. Aging. 2014, 9, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pan, J.; Liu, S.; Farkas, M.; Consugar, M.; Zack, D.J.; Kozak, I. Serum molecular signature for proliferative diabetic retinopathy in Saudi patients with type 2 diabetes. Mol. Vis. 2016, 22, 636–645. [Google Scholar]

- Shaghaghi, M.A.; Kloss, O.; Eck, P. Genetic variation in human vitamin C transporter genes in common complex diseases. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murgia, C.; Adamski, M.M. Translation of nutritional genomics into nutrition practice: The next step. Nutrients 2017, 9, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, M.; Kawasaki, R.; Rogers, S.; Man, R.E.; Itakura, K.; Xie, J. The associations of dietary intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids with diabetic retinopathy in well-controlled diabetes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 7439–7473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-López, A.; Babio, N.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Corella, D.; Amor, A.J.; Fitó, M. Mediterranean diet, retinopathy, nephropathy, and microvascular diabetes complications: A post hoc analysis of a randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2015, 38, 2134–2141, Erratum in Diabetes Care. 2018, 41, 2260–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wong, M.Y.Z.; Man, R.E.K.; Fenwick, E.K.; Gupta, P.; Li, L.J.; van Dam, R.M.; Chong, M.F.; Lamoureux, E.L. Dietary intake and diabetic retinopathy: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0186582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Egea, J.; Fabregat, I.; Frapart, Y.M.; Ghezzi, P.; Görlach, A.; Kietzmann, T. A European contribution to the study of ROS: A summary of the findings and prospects for the future from the COST action BM1203 (EU-ROS). Redox Biol. 2017, 13, 94–162, Erratum in Redox Biol. 2018, 14, 694–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domanico, D.; Fragiotta, S.; Cutini, A.; Carnevale, C.; Zompatori, L.; Vingolo, E.M. Circulating levels of reactive oxygen species in patients with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy and the influence of antioxidant supplementation: 6-month follow-up. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 63, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Medina, J.J.; Rubio-Velazquez, E.; Foulquie-Moreno, E.; Casaroli-Marano, R.P.; Pinazo-Durán, M.D.; Zanón-Moreno, V.; Del-Rio-Vellosillo, M. Update on the effects of antioxidants on diabetic retinopathy: In vitro experiments, animal studies and clinical trials. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrea, F.; Sartini, S.; Piano, I.; Franceschi, M.; Quattrini, L.; Guazzelli, L.; Ciccone, L.; Orlandini, E.; Gargini, C.; la Motta, C.; et al. 1 Oxy-imino saccharidic derivatives as a new structural class of aldose reductase inhibitors endowed with anti-oxidant activity. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2020, 35, 1194–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Albarral, J.A.; de Hoz, R.; Ramírez, A.I.; López-Cuenca, I.; Salobrar-García, E.; Pinazo-Durán, M.D.; Ramírez, J.M.; Salazar, J.J. Beneficial effects of saffron (Crocus sativus L.) in ocular pathologies, particularly neurodegenerative retinal diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2020, 15, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.J.; Lin, C.W.; Cho, S.L.; Yang, W.S.; Yang, C.M.; Yang, C.H. Protective effect of fenofibrate on oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in retinal-choroidal vascular endothelial cells: Implication for diabetic retinopathy treatment. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nebbioso, M.; Lambiase, A.; Armentano, M.; Tucciarone, G.; Bonfiglio, V.; Plateroti, R.; Alisi, L. The complex relationship between diabetic retinopathy and high-mobility group box: A review of molecular pathways and therapeutic strategies. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hee, M.R.; Izatt, J.A.; Swanson, E.A.; Huang, D.; Schuman, J.S.; Lin, C.P.; Puliafito, C.A.; Fujimoto, J.G. Optical coherence tomography of the human retina. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1995, 113, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, G.E. Optical coherence tomography findings in diabetic retinopathy. Dev. Ophthalmol 2007, 39, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arévalo, J.F. Diabetic macular edema: Changing treatment paradigms. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2014, 25, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgili, G.; Menchini, F.; Casazza, G.; Hogg, R.; Das, R.R.; Wang, X.; Michelessi, M. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) for detection of macular oedema in patients with diabetic retinopathy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 1, CD008081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ma, B.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, D.; Wang, Z.; Xu, X. Analysis of changes in retinal thickness in Type 2 diabetes without diabetic retinopathy. J. Diabetes Res. 2018, 2018, 3082893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujosevic, S.; Muraca, A.; Alkabes, M.; Villani, E.; Cavarzeran, F.; Rossetti, L.; de Cilla, S. Early microvascular and neural changes in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus without clinical signs of diabetic retinopathy. Retina 2019, 39, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T.M.; Marques, J.P.; Soares, M.; Simão, S.; Melo, P.; Martins, A.; Figueira, J.; Murta, J.N.; Silva, R. Macular OCT-angiography parameters to predict the clinical stage of nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy: An exploratory analysis. Eye 2019, 33, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschos, M.M.; Dettoraki, M.; Tsatsos, M.; Kitsos, G.; Kalogeropoulos, C. Effect of carotenoids dietary supplementation on macular function in diabetic patients. Eye Vis. 2017, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossino, M.G.; Casini, G. Nutraceuticals for the treatment of diabetic retinopathy. Nutrients 2019, 11, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laubertová, L.; Koňariková, K.; Gbelcová, H.; Ďuračková, Z.; Muchová, J.; Garaiova, I.; Žitňanová, I. Fish oil emulsion supplementation might improve quality of life of diabetic patients due to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Nutr. Res. 2017, 46, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, R.; Monte, M.D.; Lulli, M.; Raffa, V.; Casini, G. Nanoparticle-mediated delivery of neuroprotective substances for the treatment of diabetic retinopathy. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi Falavarjani, K.; Nguyen, Q.D. Adverse events and complications associated with intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF agents: A review of literature. Eye 2013, 27, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dolz-Marco, R.; Gallego-Pinazo, R.; Pinazo-Durán, M.D.; Pons-Vazquez, S.; Domingo-Pedrol, J.; Diaz-Llopis, M. Intravitreal docosahexaenoic acid in a rabbit model: Preclinical safety assessment. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hierro, C.; Monte, M.J.; Lozano, E.; Gonzalez-Sanchez, E.; Marin, J.J.; Macias, R.I. Liver metabolic/oxidative stress induces hepatic and extrahepatic changes in the expression of the vitamin C transporters SVCT1 and SVCT2. Eur. J. Nutr. 2014, 53, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| INCLUSION |

| Males/Females, aged > 25 and < 80 years with type 2 diabetes, as the TDM2 group. |

| Healthy individuals, as the CG. |

| No comorbidities. No ocular surgery or laser for 12 months (at least). No other oral supplements with antioxidants and/or omega 3 fatty acids, including vitamins in eyedrops. |

| Provided written informed consent before starting any related activities. |

| Participants able to attend the visits and to follow the study guidelines during the study period. |

| EXCLUSION |

| Males and females, aged < 25 years and > 80 years. |

| T1DM patients. |

| Patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macular edema, or ocular or systemic diseases or aggressive treatments. Previous ocular surgery or laser for 12 months (at least). Other oral supplements with antioxidants and/or omega 3 fatty acids, including vitamins in eyedrops. |

| No acceptance for the study participation and/or not signing the informed consent. Unable to attend the visits or to follow the study guidelines during the study period. |

| VARIABLES | T2DM | CG | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 38-Months | Baseline | 38-Months | End of Study | |

| AgeYears | 60 (10) | 65 (8) | 55 (12) | 60 (8) | 0.765 |

| Gender % women | 51 | 54 | 47 | 58 | 0.841 |

| DM Fam. Hist. % | 60 | 62 | 37 | 35 | 0.00001 ** |

| DM durationYears | 14 (3) | 18 (5) | - | - | - |

| BMI Kg/mm2 | 30 (3) | 30 (4) | 24 (3) | 21 (3) | 0.001 * |

| Physical Ex. % | 38 | 35 | 42 | 43 | 0.916 |

| Glycemia mg/dL | 146 (62) | 140 (8) | 89 (12) | 91 (3) | 0.000001 ** |

| HbA1c % | 9 (1) | 7 (1) | 6 (0.3) | 5 (0.3) | 0.000001 ** |

| Variables | T2DM | CG | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 38-Months | Baseline | 38-Months | End of Study | ||||

| +A/ω3 | −A/ω3 | +A/ω3 | −A/ω3 | +A/ω3 | −A/ω3 | |||

| BCVA REdecimal scale | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.002 ** | 0.002 ** |

| BCVA LEdecimal scale | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.049 * | 0.001 ** |

| IOP RE mm Hg | 15 (2) | 15 (2) | 15 (2) | 15 (2) | 14 (2) | 15 (3) | 0.415 | 0.432 |

| IOP LE mm Hg | 15 (2) | 16 (2) | 15 (2) | 16 (2) | 13 (2) | 16 (2) | 0.068 | 0.453 |

| CMT RE µm | 252 (32) | 245 (29) | 240 (28) | 251 (33) | 253 (35) | 258 (40) | 0.585 | 0.514 |

| CMT LE µm | 258 (55) | 242 (37) | 236 (46) | 255 (36) | 255 (43) | 249 (35) | 0.539 | 0.561 |

| T2DM Patients + DR (n = 129) | T2DM Patients − DR (n = 158) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DR Impairment: 22% | DR Impairment: 27% | ||||||||||

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||||||

| 13% | 5% | 4% | 12% | 9% | 5% | ||||||

| +A/ω3 | −A/ω3 | +A/ω3 | −A/ω3 | +A/ω3 | −A/ω3 | +A/ω3 | −A/ω3 | +A/ω3 | −A/ω3 | +A/ω3 | −A/ω3 |

| 3% | 10% | 2% | 3% | 1% | 3% | 3% | 9% | 2% | 7% | 2% | 3% |

| VARIABLES | T2DM 38-Months | CG 38-Months | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +DR | −DR | +A/ω3 | −A/ω3 | End of study | |||

| +A/ω3 | −A/ω3 | +A/ω3 | −A/ω3 | ||||

| MDA/TBARS (µM) | 3 (0.2) | 3.7 (0.2) | 2.7 (0.2) | 3.0 (0.2) | 1.6 (0.1) | 2.0 (0.1) | 0.001 ** |

| TAC (mM) | 1.8 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) | 2.0 (0.1) | 1.5 (0.1) | 3.2 (0.2) | 2.8 (0.2) | 0.001 ** |

| GSH (µM) | 1.4 (0.6) | 0.9 (0.7) | 1.6 (0.1) | 1.4 (0.1) | 2.7 (0.2) | 2.3 (0.2) | 0.842 |

| Vit C (µmol/mL) | 45 (18) | 33 (15) | 43 (16) | 40 (21) | 59 (20) | 56 (20) | 0.001 ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sanz-González, S.M.; García-Medina, J.J.; Zanón-Moreno, V.; López-Gálvez, M.I.; Galarreta-Mira, D.; Duarte, L.; Valero-Velló, M.; Ramírez, A.I.; Arévalo, J.F.; Pinazo-Durán, M.D.; et al. Clinical and Molecular-Genetic Insights into the Role of Oxidative Stress in Diabetic Retinopathy: Antioxidant Strategies and Future Avenues. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9111101

Sanz-González SM, García-Medina JJ, Zanón-Moreno V, López-Gálvez MI, Galarreta-Mira D, Duarte L, Valero-Velló M, Ramírez AI, Arévalo JF, Pinazo-Durán MD, et al. Clinical and Molecular-Genetic Insights into the Role of Oxidative Stress in Diabetic Retinopathy: Antioxidant Strategies and Future Avenues. Antioxidants. 2020; 9(11):1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9111101

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanz-González, Silvia M., José J. García-Medina, Vicente Zanón-Moreno, María I. López-Gálvez, David Galarreta-Mira, Lilianne Duarte, Mar Valero-Velló, Ana I. Ramírez, J. Fernando Arévalo, María D. Pinazo-Durán, and et al. 2020. "Clinical and Molecular-Genetic Insights into the Role of Oxidative Stress in Diabetic Retinopathy: Antioxidant Strategies and Future Avenues" Antioxidants 9, no. 11: 1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9111101

APA StyleSanz-González, S. M., García-Medina, J. J., Zanón-Moreno, V., López-Gálvez, M. I., Galarreta-Mira, D., Duarte, L., Valero-Velló, M., Ramírez, A. I., Arévalo, J. F., Pinazo-Durán, M. D., & on behalf of the Valencia Study Group on Diabetic Retinopathy (VSDR) Report number 4. (2020). Clinical and Molecular-Genetic Insights into the Role of Oxidative Stress in Diabetic Retinopathy: Antioxidant Strategies and Future Avenues. Antioxidants, 9(11), 1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9111101