1. Introduction

Vitamin D

3 is a liposoluble compound required for the absorption of calcium and phosphorus in the intestines. It is biologically inert and must be metabolized to 25-hydroxyvitamin D

3 in the liver and then to 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D

3 in the kidney in order to be activated [

1]. Recent studies confirm the important physiological functions of this vitamin, which has been related to immunity control [

2] and its deficiency could lead to several health disorders [

3]. Moreover, it has been reported that this vitamin is involved in stress regulation, due to the similarities of its nuclear receptor ligand to those of corticosteroids, which act on the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis [

4]. The similarities between these receptors mean that both substances compete and one or the other can be used in case of intoxication or overdose [

5]. Consequently, this vitamin could be a potential mechanism used in intensive production practices that cause stress and affect the quality of the products. Recently, the protective effect of vitamin D against oxidative stress [

6] has been reported in humans, as well as its direct association with increased glutathione-peroxidase levels, which is one of the main antioxidant enzymes in the organism [

7]. However, such effects and the persistence of possible antioxidant properties after slaughter have been scarcely studied in animals and results are not conclusive.

Additionally, one of the dietary strategies based on vitamin D supplementation in animal diets is its application to improve tenderness as a result of enhanced post-mortem proteolysis [

8]. This is based on the activation of the Ca

2+ ions by vitamin D

3, which are responsible for activation of enzymes from the calpain group that mediates the degradation of myofibrillar and cytoskeletal proteins post-mortem [

9]. In addition, vitamin D may indirectly modify other meat quality characteristics such as drip loss since the enhancement in muscle proteolysis has been associated with increased water retention [

10] and juiciness.

In the majority of the studies on vitamin D

3 supplementation, high doses are added into the diets, and there is a lack of information of the possible effects when administered in drinking water at high concentrations for a short period. In a previous study, one-time dose of 40,000 IU resulted in fewer piglets losing weight during the first 7 days post-weaning [

11]. Considering that supra-nutritional doses may retard growth [

12], and that stress prior to slaughter in fasting conditions may modify the animal’s oxidative status and, consequently, the stability and nutrient value of the products, its administration under these special conditions deserves more attention. Accordingly, drinking water could be an interesting vehicle for providing short-term vitamin D

3 supplementation to fasted pigs without compromising growth and with possible beneficial effects on meat quality.

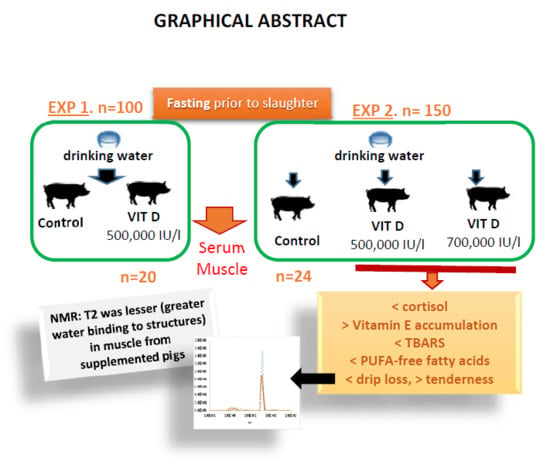

Therefore, the objectives of this study were to investigate the effect of vitamin D3 administration—added to drinking water at different doses during lairage prior to slaughter—on physiological stress, oxidative status, and meat quality characteristics such as pH, drip loss, muscle composition, meat stability, and tenderness.

4. Discussion

The strategy of supplementing pigs’ drinking water with vitamin D

3 prior to slaughter during fasting was evaluated in the present research in two experiments, since results may depend not only on the supplementation dose but also on the pigs’ water intake in relation to climatic conditions. The intake of amounts above 500,000 IU/day of vitamin D

3 into drinking water decreased serum cortisol and increased α-tocopherol. Stressful situations such as fasting conditions prior to slaughter have been reported to increase cortisol levels in relation to the changes in certain nutrients with regulatory functions in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis [

21,

22]. The effectiveness of vitamin D supplementation to reduce serum cortisol has been reported in some studies in humans [

4,

23] because both compounds compete for similar receptor sites [

5]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of information on the possible effect of its application in animal production practices. In suckling piglets after a single oral administration of 40,000 IU at 2 days of age, it was observed that these were heavier than untreated piglets at weaning and 7 days post-weaning; and authors suggested that more studies were needed to understand this effect of vitamin D under stress conditions [

11]. The present research shows that doses above 500,000 IU/animal are needed in fasting pigs to observe positive effects related with stress control. In previous studies in human adults with 2000 IU/day [

23] or 4000 IU/day [

4] and, in infants with 400 IU/day combined with sunlight (7–14 h/week) [

24] decreased cortisol values were observed. However, supplementation period was 12–16 weeks in adults and 8 weeks in infants (resulting in lower total doses than those used in the present study). Moreover, stressful situations have been associated with a disruption of the antioxidant balance and decreased serum α-tocopherol concentrations [

25]. In the present research, 500,000 IU of vitamin D

3 short-term supplementation improved the oxidative status of fasted pigs as indicated by α-tocopherol values, and 800,000 IU/animal are needed to reduce MDA production. Many studies in humans reported this effect on oxidative stress in relation to vitamin D status [

26]; however, there is a lack of information in animals under stressful conditions. Recent studies [

7] reported that vitamin D

3 supplementation given at different small doses up to a total of 560,000 IU during the experimental period (6 m) enhanced glutathione peroxidase enzyme in adults. In addition, it has been found that Ca

2+ may prevent lipid oxidation in vitro [

27] through its ability to interact with superoxide anion radicals, which is in line with the inverse relationship found between serum Ca

2+ and MDA values in the present study. In addition, the administration of calcium plus vitamin D supplements (50,000 IU twice during the study) produced in humans a significant increase in GSH and prevented a rise in MDA concentration [

28]. However, other authors have not found such a relationship when providing high levels of vitamin D

3 in beef cattle [

29]. Furthermore, according to our results, the higher serum concentrations of α-tocopherol observed in pigs that consumed at least 800,000 IU of vitamin D

3 in drinking water prior to slaughter may explain in part the lower MDA production in supplemented pigs during fasting. Some studies reported the effectiveness of vitamin E to control oxidative stress in piglets under stressful conditions [

25]. The previous literature reported that vitamin D reduces vitamin E uptake [

30] because these vitamins share common transport proteins. However, these effects have been reported in animals receiving food and not in fasting conditions. According to the results of the present study, the physiological stress and oxidative status control in fasting conditions by adding vitamin D

3 to water might have beneficial effects on vitamin E serum preservation. Therefore, administration of vitamin D

3 to drinking water prior to slaughter may be an interesting strategy to improve vitamin E levels.

The antioxidant effect of vitamin D

3 inclusion into water was also observed in meat after 800,000 IU of vitamin D

3/animal intake (experiment 2). Hence, meat from pigs supplemented with 500,000 IU/L or with 700,000 IU/L, with a consumption of at least 800,000 IU/animal had lower MDA levels on day 5 of refrigerated storage. These groups also had higher levels of α-tocopherol in meat and these values were inversely correlated with meat oxidation; whereas no correlations were observed between meat MDA and serum vitamin D levels. Other authors have reported the relationship between blood α-tocopherol levels and α-tocopherol accumulation in tissues [

31,

32] and the potent antioxidant effect of this vitamin on meat lipid oxidation [

31,

32,

33]. However, there is a lack of information in the literature regarding the effects of vitamin D supplementation in drinking water on muscle α-tocopherol concentrations. Taking into account that stressful conditions, such as fasting, may increase cortisol levels [

21,

22], oxidative stress [

22,

34], and disrupt oxidant/antioxidant equilibrium [

22,

25], and the positive effect of vitamin D on controlling physiological stress [

23] and antioxidant enzymes in vivo [

7], the administration of this vitamin could also be of interest to preserve muscle tocopherol concentrations and meat stability.

To the best of our knowledge, there is not much information on the possible effects of vitamin D

3 supplementation on meat lipid oxidation. One of the studies carried out on beef [

29] found a pro-oxidant effect of vitamin D

3 supplementation in the diet when using doses of 7 million IU/day/animal for 3 or 6 days or 1 million IU/day/animal for 9 days. This is significantly higher than the lowest dose used in the present study per animal (500,000 IU) in short-term administration. However, another study carried out in pigs [

35] reported increased antioxidant capacity in meat from pigs receiving 50 µg of vitamin D

3/kg of feed (2 million IU/kg) for 55 days, and authors explained this antioxidant effect by the higher DPPH antioxidant activity of this form of vitamin. Lahucky et al. [

36], reported a slight antioxidant effect in pigs receiving 500,000 IU of vitamin D

3/day, compared with a control group or with a group supplemented with vitamin E, although the supplementation time for the vitamin D

3-supplemented group was 5 days (lower than the vitamin E supplemented animals). The lack of significant effects on oxidation as an effect of the supplementation dose (500,000 IU/L vs. 700,000 IU/L) of the present study could be possibly explained either by the saturation effect when vitamin D

3 was solubilized in water or more likely by the period of supplementation. A peak absorption in plasma at 6 h with an absorption range between 45% and 100% 3 h after the oral dose, and a net mean value of 78.6% with supplementation doses of 0.5–1 mg of Vitamin D

3 has been reported in humans [

37]. In pigs, an absorption of 50% of vitamin D administered orally has been documented [

38]. However, the increase in vitamin D

3 absorption depends on the basal levels [

39,

40]. Therefore, the higher the basal levels the lower the absorption. This leads us to believe that the use of high doses or prolonged administration may not produce the expected positive effects. Hence, Tipton et al. [

41] suggested vitamin D

3 supplement withdrawal some days before slaughter to achieve improvements in meat quality. Another important observation of the results presented is that the antioxidant effect of vitamin D

3 supplementation was more significant in experiment 2 than in experiment 1. These experiments were carried out at different times and there was different water intake because of climate conditions (higher temperatures during the second experiment than in the first one). Moreover, the sex of the animals could affect, in part, the more significant results observed in the second experiment, since it has been reported that the favorable increase in glutathione peroxidase of vitamin D

3 supplementation was mainly found in males [

7]. The oxidative status of meat was also evaluated by the quantification of the specific free fatty acid formation. An excess of lipid oxidation induces the formation of more free fatty acids due to lipolysis and hydrolytic changes [

34], and depending on the specific free fatty acid proportions meat sensory characteristics may also be affected [

42]. In this sense, some antioxidants have shown anti-lipase activity and consequently are able to control lipid stability [

43,

44]. In the present study lower free PUFA production was observed in meat from pigs that consumed at least 500,000 IU of vitamin D when compared to the control group. In addition, both experiments showed a direct relationship between free PUFA fatty acid proportion and meat MDA concentration. A similar relation between free PUFA and TBARS production has been found in other studies [

34]. It has been reported that vitamin D may act on lipid metabolism [

45] and can rapidly accumulated in adipose tissue [

46]. However, there is no information of their possible effects on lipolysis in tissues. The higher vitamin E concentration found in meat from vitamin D supplemented pigs could contribute to control lipid stability and free fatty acid production [

44]. Moreover, an antilipolytic effect of Ca

2+ has been reported in human adipocytes mainly through the inhibition of phosphodiesterase which would result in lipolysis inhibition [

47]. The major contributors to rancidity and lipid oxidation development are polyunsaturated fatty acids [

48], which would result in different concentrations of flavor precursors and development [

42,

49]. Consequently, vitamin D

3 supplementation prior to slaughter could be an interesting strategy to improve the sensory characteristics of the products.

Concerning the proteolytic effect of vitamin D

3 supplementation in water prior to slaughter, results on MFI or drip loss in the present study indicate that the dose of 500,000 IU of vitamin D

3/l and intake of at least 800,000 IU/d under fasting would induce only minor effects on protein disruption. Drip loss was the meat quality characteristic most affected in relation to proteolytic activity, since both parameters were directly related, contrary to the inverse relation between drip loss and muscle pH [

50,

51]. Hence, meat from pigs that received vitamin D

3 supplementation tended to have higher water holding capacity although no changes were detected in terms of pH. Other authors found improved drip loss and tenderness in chicken after 100,000 IU of supplementation for 7 days [

52] and in steers [

53] using doses from 7 to 9 million for 3 or 9 days, respectively. However, in pigs Wilborn et al. [

12] only found a tendency for lower drip loss in animals supplemented with the highest dose (80,000 IU/kg feed) of vitamin D

3 for 44 days; whereas a shorter period (10 days) but higher dose (175,000 IU/kg) resulted in a lack of effects of drip loss in pork [

54]. Nevertheless, these authors found an increase in the pH range in barrows but not in gilts when compared to the control group. The use of lower doses (500,000 IU/day) for 5 days also resulted in non-significant differences in drip loss or pork pH [

36]. The effects of vitamin D on proteolysis and indirectly on water preservation of meat has been related with increased serum Ca

2+ levels [

10] that activate the calpain proteases system. This explanation would be in line with the results presented in this study, in which pigs receiving vitamin D

3 in water had higher Ca

2+ concentrations. Moreover, other authors have found that muscle with greater α-tocopherol resulted in a higher proteolytic potential [

51] which is also related to the greater muscle levels of the vitamin D-supplemented groups. Concerning the texture profile, in the present study, cohesiveness, gumminess, and chewiness decreased, in the VITD-500 group when compared to the control group (in both experiments). These texture characteristics have been reported to be decreased with ageing, a fact that reflected the progressive softness of the meat [

55] and it has been inversely correlated with initial tenderness, and rate of breakdown [

56]. Consequently, these results would indicate the positive effect on texture parameters of a short-term administration under fasting of at least 500,000 IU D

3 per animal. To our knowledge, this is the first time that the effects of vitamin D

3 supplementation in drinking water on tenderness in fasted pigs are examined. Other authors have not found effects on tenderness when using higher doses for a longer time in feed of pigs [

12,

35,

36,

54,

57]. However, these authors applied different times of feeding withdrawal prior to slaughter and, in addition, tenderness was quantified by Warner–Bratzler shear force or sensory evaluation, which have been considered less robust measurements than the texture profile analysis [

56]. Conversely, when supplementing vitamin D in feed in beef, different studies [

10,

58] reported changes in tenderness when assessed using the same methods used for pork, by Warner–Bratzler or sensory evaluation. In an interesting study carried out in cattle [

41], the oral administration of 3 million IU/d for 5 days did not modify serum Ca

2+ concentration immediately following supplementation or tenderness at day 0. However, after 7 days of supplement withdrawal serum Ca

2+ increased and muscles from animals supplemented with vitamin D

3 had lower Warner–Bratzler shear force values than the muscles from non-supplemented. Conversely, in pigs, Wiegand et al. [

57] reported that the effective dose needed to raise blood plasma calcium concentration was at least 500,000 IU D

3/d, and this dose applied for a short-term period (3 days) maintained plasma calcium for the longest time after cessation of vitamin D

3 feeding. However, these authors did not find significant differences in tenderness even though the calcium increased. These effects suggest that regulation of calcium transport from plasma to muscle and its hormonal control deserves further investigation in pigs.

Furthermore, a structural muscle magnetic resonance imaging analysis was carried out to study the possible effects of the dose of vitamin D

3 on water holding capacity and its subsequent effects on proteolysis. This analysis revealed that transverse relaxation time (T2) was shorter in muscle from pigs supplemented with vitamin D

3 in water and these values also decreased with storage time. T2 is associated with the extent of the relationship between water and peripheral structures and water compartmentalization and it has been reported that T2 values strongly correlate with bulk water [

59] and inversely with water holding capacity [

60]. Hence, high T2 means a lower degree of water binding to structures and consequently higher drip loss as observed in the control group of the present study. It is not clear whether these effects are due to vitamin D

3 antioxidant protection on other antioxidant vitamins or proteolytic enzymes such as calpain; since it has been reported that vitamin E and selenium may protect calpain oxidation and then enhance muscle proteolysis and water retention [

40]. Even though no differences were observed in the MRI parameters after the slaughter of the animal (first 2 days), the treatment applied would not affect the retention of the free water and the associated drip losses. However, after these first losses, the integrity of the structures would provide greater retention of aqueous content.