Application of Membrane Capacitive Deionization as Pretreatment Strategy for Enhancing Salinity Gradient Power Generation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Feed Solutions

2.1.1. Low TDS Solution (BWRO Brine)

2.1.2. High TDS Solution (Synthetic SWRO Brine)

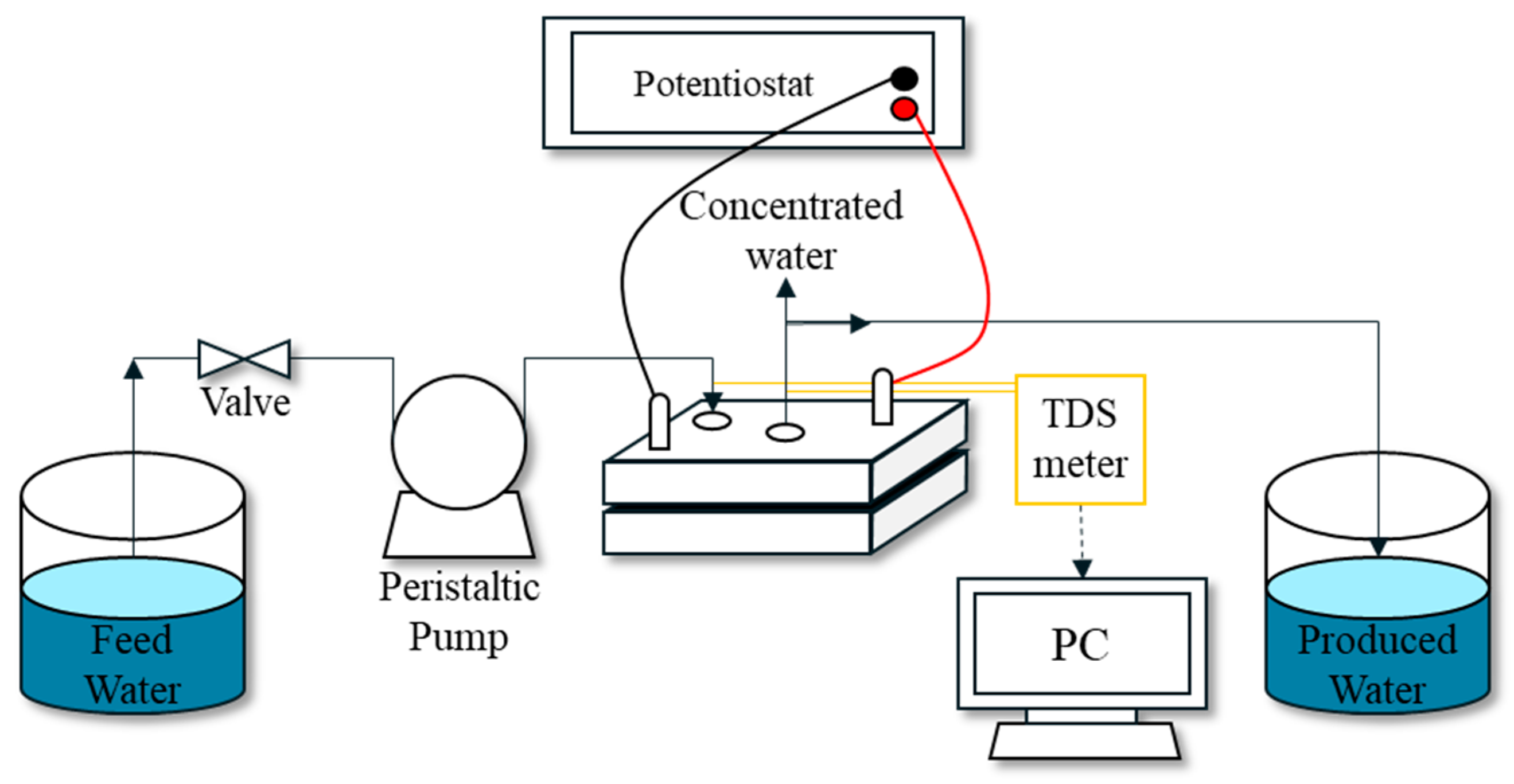

2.2. Lab-Scale MCDI System

2.2.1. MCDI Module

2.2.2. MCDI Experimental Setup

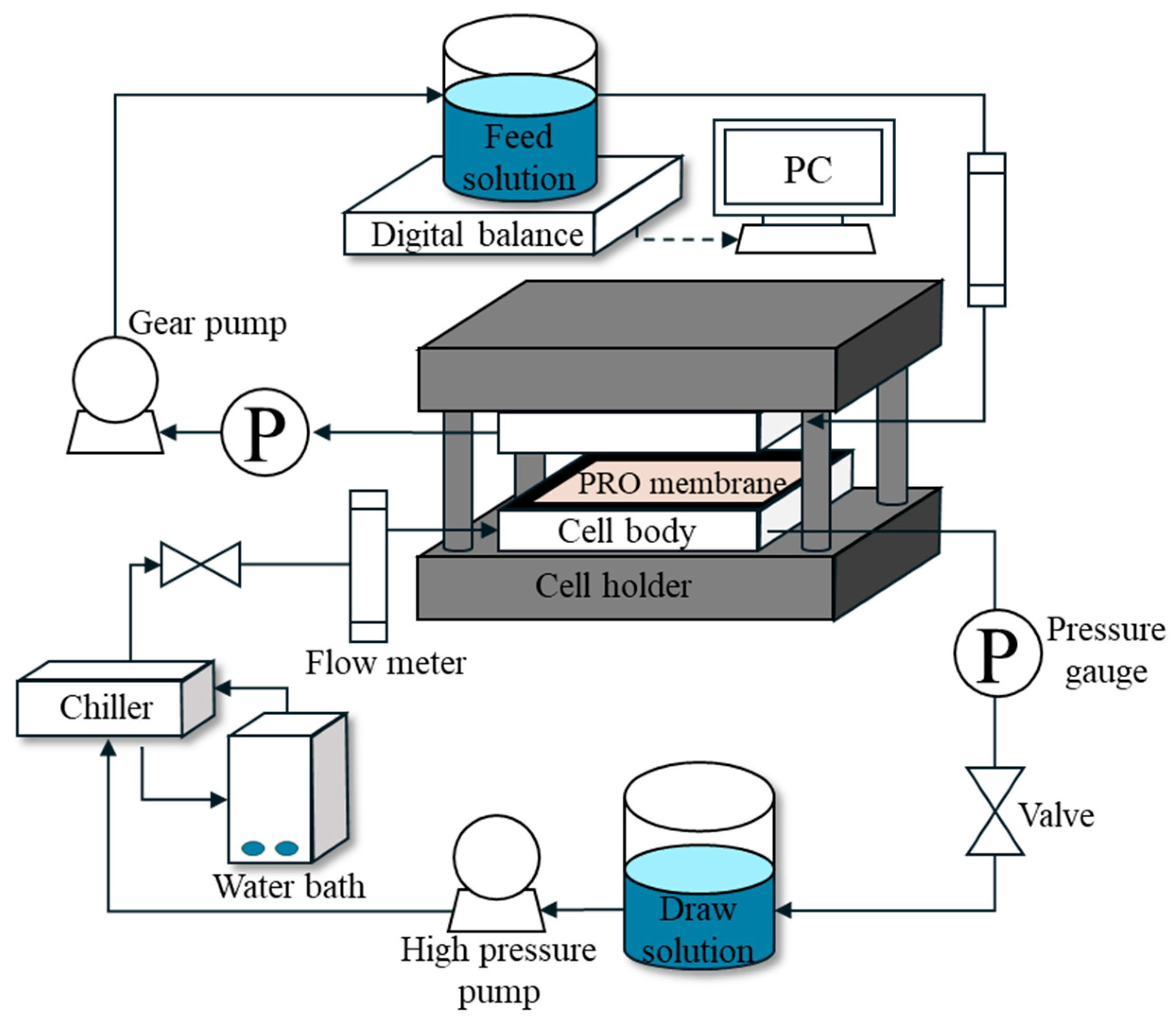

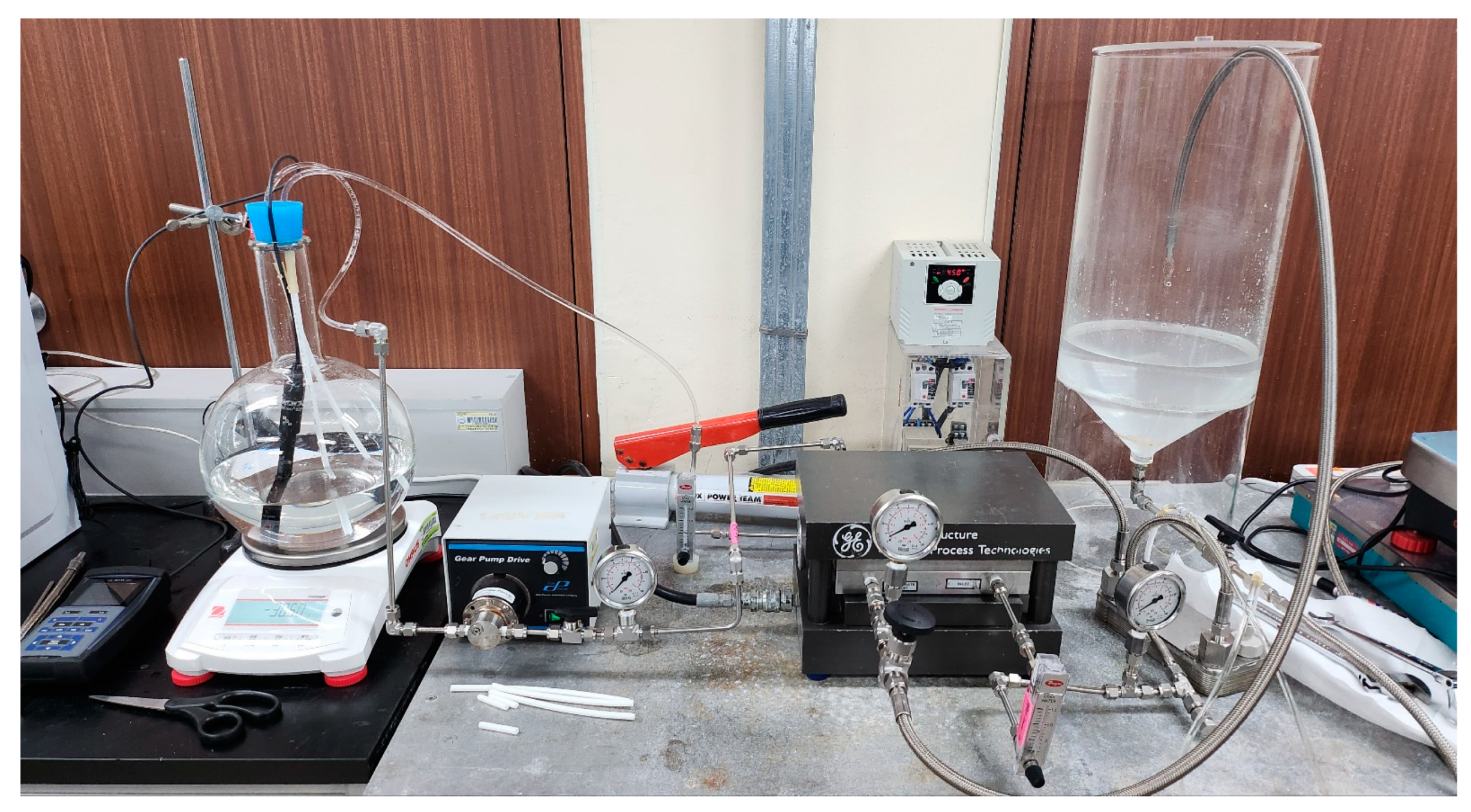

2.3. Lab-Scale PRO System

2.3.1. PRO Membranes

2.3.2. PRO Experimental Setup

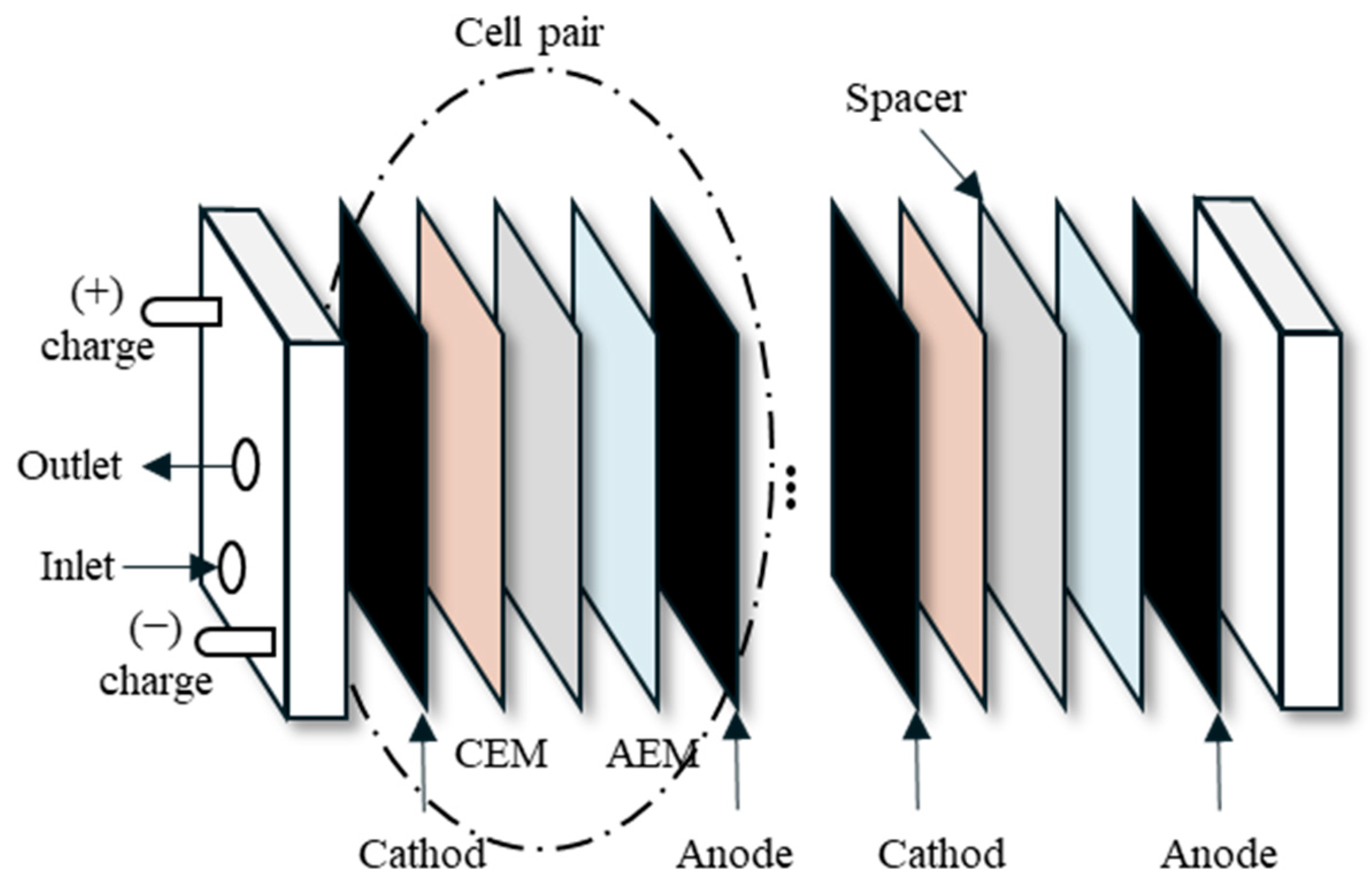

2.4. Lab-Scale RED System

2.4.1. Ion Exchange Membranes

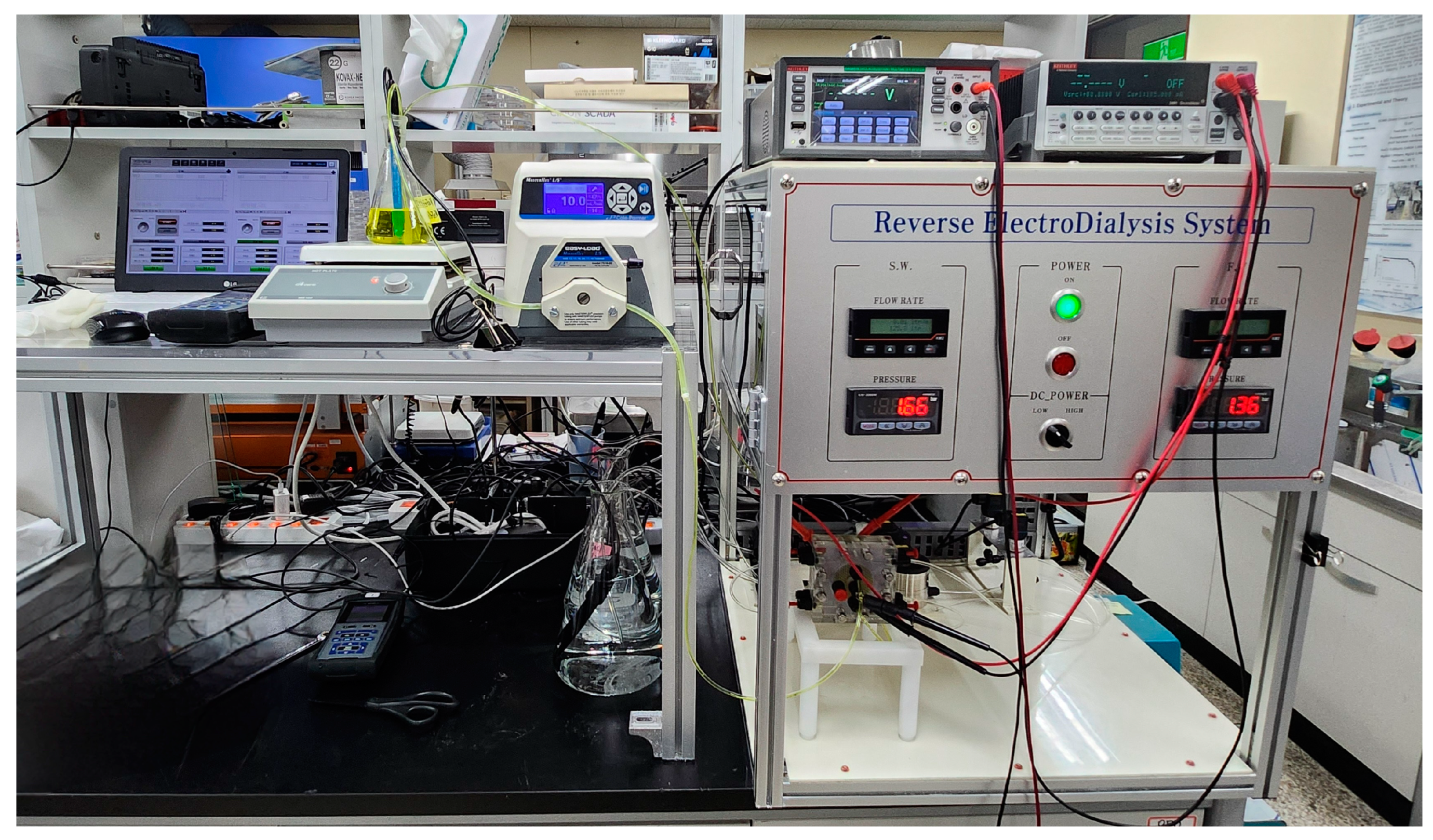

2.4.2. RED Experimental Setup

2.5. Experimental Conditions

2.5.1. MCDI Process

2.5.2. PRO Process

2.5.3. RED Process

2.6. Measurements and Observation

2.6.1. Electrical Resistance of IEMs

2.6.2. Power Density

2.6.3. Specific Energy Consumption

2.6.4. Examination of Membranes Surface

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Pretreatment of BWRO Brine by MCDI

3.2. PRO Experiments

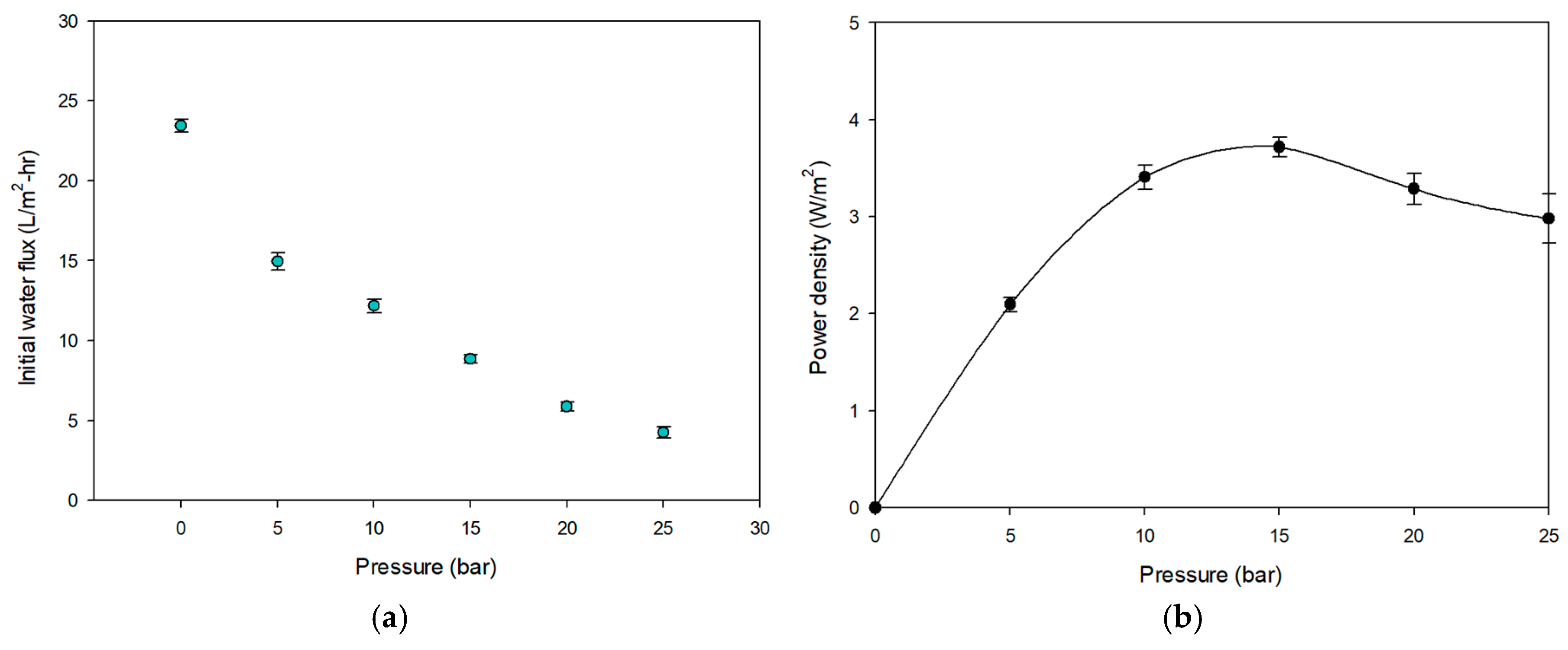

3.2.1. Flux and Power Density of PRO System

3.2.2. Fouling in PRO System

3.3. RED Experiments

3.3.1. OCV of RED System

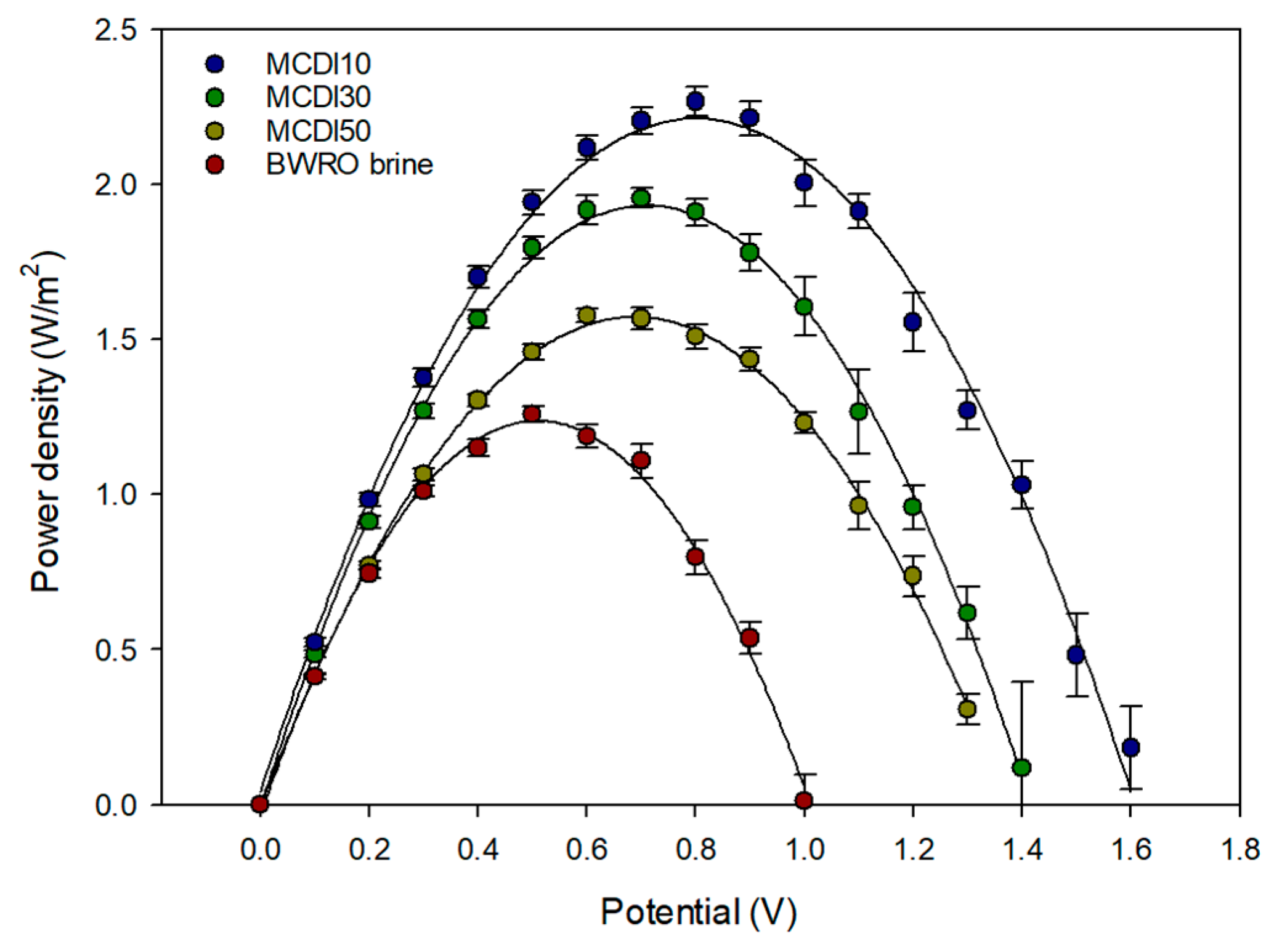

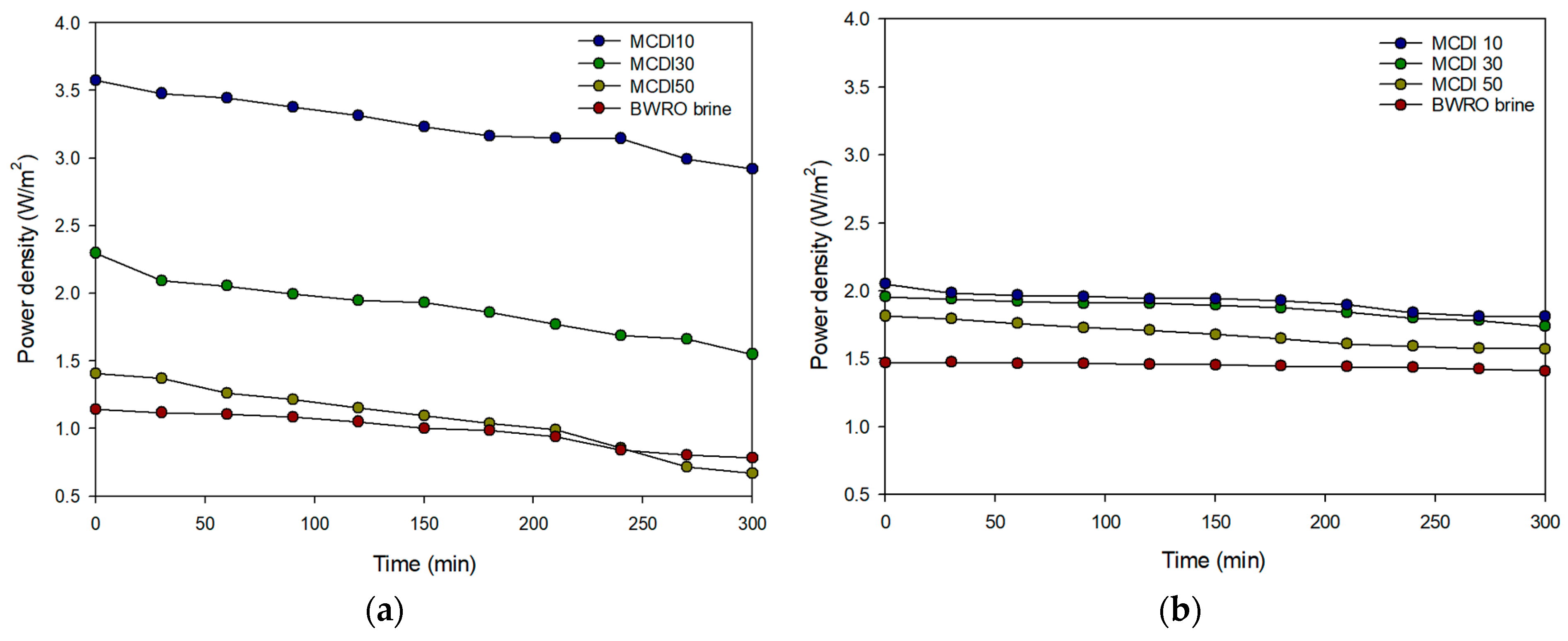

3.3.2. Power Density of RED System

3.3.3. Electrical Resistance of RED System

3.4. Comparison of Power Density Between PRO and RED

3.4.1. PRO System

3.4.2. RED System

3.4.3. Comparison of MCDI Pretreatment Efficiency for PRO and RED

3.5. Examination of PRO and RED Membranes

3.5.1. Visual Examination of PRO Membranes

3.5.2. SEM Analysis of PRO Membranes

3.5.3. Visual Examination of RED Membranes

3.5.4. SEM Analysis of RED Membranes

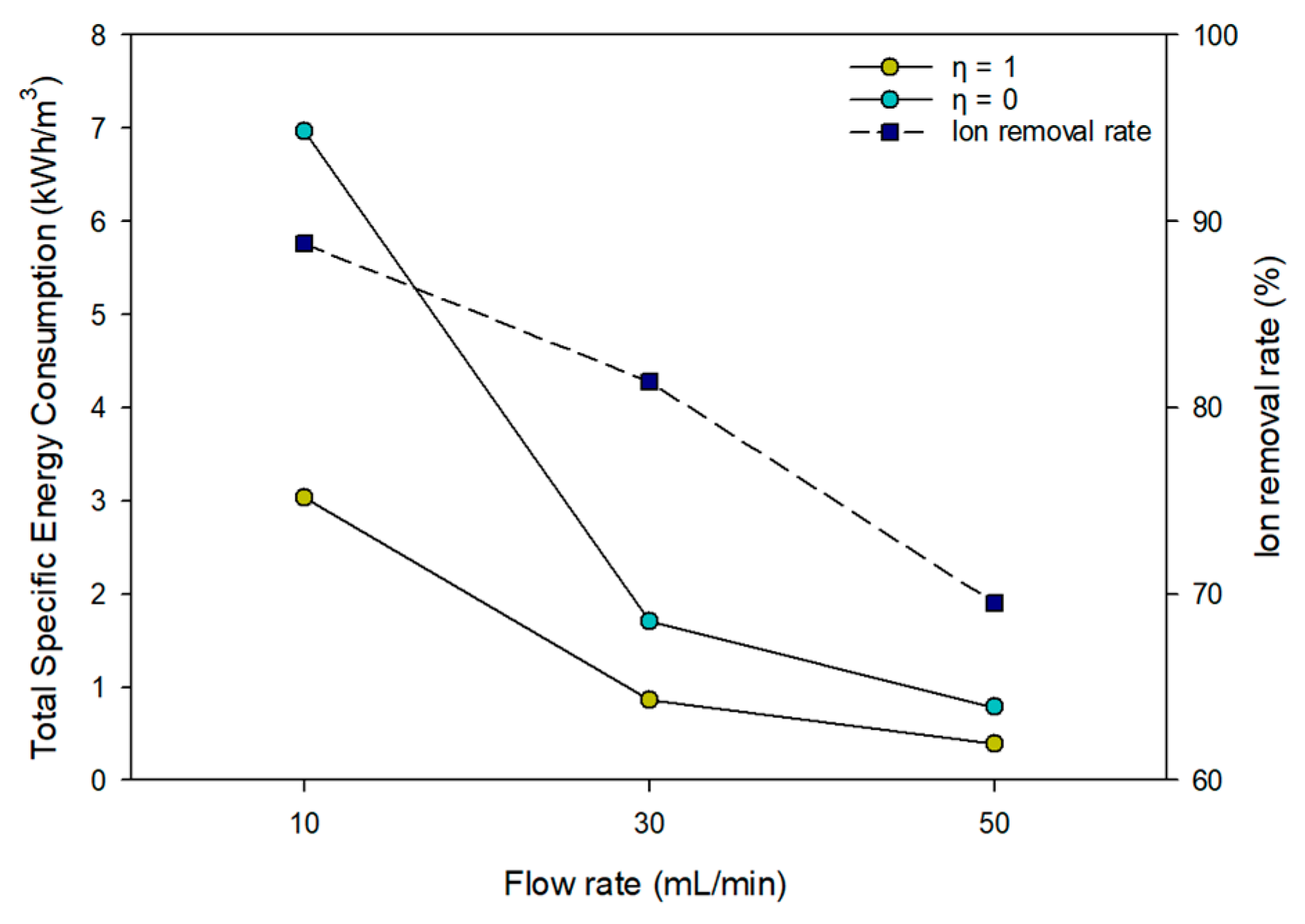

3.6. Energy Efficiency

3.6.1. Specific Energy Consumption for MCDI

3.6.2. Specific Energy Generation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IEA. CO2 Emissions in 2023; IEA: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. CO2 and Other Greenhouse Gas Emissions; Our World in Data: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, B.E.; Elimelech, M. Membrane-based processes for sustainable power generation using water. Nature 2012, 488, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattle, R. Production of electric power by mixing fresh and salt water in the hydroelectric pile. Nature 1954, 174, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuleszo, J.; Kroeze, C.; Post, J.; Fekete, B.M. The potential of blue energy for reducing emissions of CO2 and non-CO2 greenhouse gases. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2010, 7 (Suppl. S1), 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampedro, T.; Tristán, C.; Gómez-Coma, L.; Fallanza, M.; Ortiz, I.; Ibañez, R. Design of a Reverse Electrodialysis Plant for Salinity Gradient Energy Extraction in a Coastal Wastewater Treatment Plant. Membranes 2023, 13, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, S.-C.; Huang, W.-Z.; Lin, G.-S.; Wang, Z.; Tung, K.-L.; Chuang, C.-J. Evaluation of the Sp7ecific Energy Consumption of Sea Water Reverse Osmosis Integrated with Membrane Distillation and Pressure–Retarded Osmosis Processes with Theoretical Models. Membranes 2022, 12, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drioli, E.; Giorno, L.; Fontananova, E. 3.8 Membrane-Based Processes for Sustainable Power Generation Using Water: Pressure-Retarded Osmosis (PRO), Reverse Electrodialysis (RED), and Capacitive Mixing (CAPMIX). In Comprehensive Membrane Science and Engineering, 2nd ed.; Drioli, E.; Giorno, L.; Fontananova, E. Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 206–248. [Google Scholar]

- Salih, M.H.; Hassan, H.A.; Al-Alawy, R.M.; Zaboon, S.; Al-Alawy, A.F.; Al-Jendeel, H.A. Green power generation from the Tigris River using pressure retarded osmosis process. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 320, 100887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.N.; Saleem, H.; Zaidi, S.J. Progress in membranes for pressure retarded osmosis application. Desalination 2023, 549, 116347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazif, A.; Karkhanechi, H.; Saljoughi, E.; Mousavi, S.M.; Matsuyama, H. Recent progress in membrane development, affecting parameters, and applications of reverse electrodialysis: A review. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 47, 102706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi-Garravand, E.; Mulligan, C.N. Feasibility of Pressure-Retarded Osmosis for Electricity Generation at Low Temperatures. Membranes 2021, 11, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, P.; Cath, T.Y.; Ladner, D.A. Mass Transport in Osmotically Driven Membrane Processes. Membranes 2021, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, S.; Kim, H.; Gi Hong, J.; Jang, J.; Higa, M.; Pishnamazi, M.; Choi, J.-Y.; Chandula Walgama, R.; Bae, C.; Kim, I.S.; et al. Clean power generation from salinity gradient using reverse electrodialysis technologies: Recent advances, bottlenecks, and future direction. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Yang, S.; Choi, J.; Kim, J.-O.; Jeong, N. Optimization of the number of cell pairs to design efficient reverse electrodialysis stack. Desalination 2021, 497, 114676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Das, P.P.; Chakraborty, A.; Purkait, M.K. Clean energy from salinity gradients using pressure retarded osmosis and reverse electrodialysis: A review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 49, 101687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliavini, M.; Babler, M.U. Low-Concentration Ozonation as a Feed Pretreatment Strategy to Reduce Organic Fouling in Pressure-Retarded Osmosis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 16317–16327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, S.; Tufa, R.A.; Avci, A.H.; Fontananova, E.; Di Profio, G.; Curcio, E. Fouling propensity in reverse electrodialysis operated with hypersaline brine. Energy 2021, 228, 120563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vital, B.; Baron, A.M.; Kuntke, P.; Gagliano, M.C.; Hamelers, H.V.M.; Sleutels, T. Evaluation of chemical free cleaning techniques for reverse electrodialysis stacks fed with natural waters. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 61, 105236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Choi, Y.; Lee, S.; Jeong, N. Comparison of fouling characteristics between reverse electrodialysis (RED) and pressure retarded osmosis (PRO). Desalination 2021, 497, 114648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbari-Sisakht, M.; Ismail, A.F. A comprehensive review of pressure and osmosis driven membrane processes: Processes, characteristics and materials. Desalination 2025, 598, 118427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaber, R.I.; Phuong Pham Le, T.; Alhseinat, E.; Nogueira, R.P.; Shetty, D.; Hasan, S.W.; Banat, F. Energy recovery from produced water via reverse Electrodialysis: The role of heavy metals and soluble organics on process performance. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 293, 117433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, P.; Lau, W.; Othman, M.; Ismail, A. Membrane fouling in desalination and its mitigation strategies. Desalination 2018, 425, 130–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSawaftah, N.; Abuwatfa, W.; Darwish, N.; Husseini, G. A comprehensive review on membrane fouling: Mathematical modelling, prediction, diagnosis, and mitigation. Water 2021, 13, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardor, D.; Al Maas, M.; Minier-Matar, J.; Janson, A.; Abdel-Wahab, A.; Shon, H.K.; Adham, S. Evaluation of pretreatment and membrane configuration for pressure-retarded osmosis application to produced water from the petroleum industry. Desalination 2021, 516, 115219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.L.; Li, X.; Chung, T.-S. The forward osmosis-pressure retarded osmosis (FO-PRO) hybrid system: A new process to mitigate membrane fouling for sustainable osmotic power generation. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 559, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Choi, Y.; Lee, S. Treatment of Semiconductor Wastewater Containing Tetramethylammonium Hydroxide (TMAH) Using Nanofiltration, Reverse Osmosis, and Membrane Capacitive Deionization. Membranes 2023, 13, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañas Kurz, E.E.; Hellriegel, U.; Hdoufane, A.; Benaceur, I.; Anane, M.; Jaiti, F.; El-Abbassi, A.; Hoinkis, J. Comparison of Pilot-Scale Capacitive Deionization (MCDI) and Low-Pressure Reverse Osmosis (LPRO) for PV-Powered Brackish Water Desalination in Morocco for Irrigation of Argan Trees. Membranes 2023, 13, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Saidi, S.; Kyaw, H.H.; Myint, M.T.Z.; Al-Hajri, R.; Al-Abri, M. Capacitive deionization for water desalination: Optimizing operational parameters and validating the model across concentrations variant. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 514, 145614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyaw, H.H.; Al-Mashaikhi, S.M.; Myint, M.T.Z.; Al-Harthi, S.; El-Shafey, E.-S.I.; Al-Abri, M. Activated carbon derived from the date palm leaflets as multifunctional electrodes in capacitive deionization system. Chem. Eng. Process.—Process Intensif. 2021, 161, 10831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Cho, H.; Choi, Y.; Koo, J.; Lee, S. Optimization and Evaluation for the Capacitive Deionization Process of Wastewater Reuse in Combined Cycle Power Plants. Membranes 2023, 13, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; He, M.; Han, J.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H. Recent Advances in Capacitive Deionization: Research Progress and Application Prospects. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaee, A.; Millar, G.J.; Zaragoza, G. Integration and optimization of pressure retarded osmosis with reverse osmosis for power generation and high efficiency desalination. Energy 2016, 103, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touati, K.; Tadeo, F. Study of the Reverse Salt Diffusion in pressure retarded osmosis: Influence on concentration polarization and effect of the operating conditions. Desalination 2016, 389, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, A.; Tedesco, M.; Cipollina, A.; Galia, A.; Micale, G.; Scialdone, O. Reverse electrodialysis performed at pilot plant scale: Evaluation of redox processes and simultaneous generation of electric energy and treatment of wastewater. Water Res. 2017, 125, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermaas, D.A.; Saakes, M.; Nijmeijer, K. Doubled power density from salinity gradients at reduced intermembrane distance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 7089–7095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veerman, J.; Saakes, M.; Metz, S.; Harmsen, G. Reverse electrodialysis: A validated process model for design and optimization. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 166, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.-H.; Hwang, K.-s.; Jeong, H.; Byeon, S.-Y.; Nam, J.-Y.; Kim, C.-S.; Kim, H.; Yang, S.; Choi, J.Y.; Jeong, N. Electrode system for large-scale reverse electrodialysis: Water electrolysis, bubble resistance, and inorganic scaling. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2019, 49, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platek-Mielczarek, A.; Lang, J.; Töpperwien, F.; Walde, D.; Scherer, M.; Taylor, D.P.; Schutzius, T.M. Engineering Electrode Rinse Solution Fluidics for Carbon-Based Reverse Electrodialysis Devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 48826–48837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickenbottom, K.L.; Vanneste, J.; Elimelech, M.; Cath, T.Y. Assessing the current state of commercially available membranes and spacers for energy production with pressure retarded osmosis. Desalination 2016, 389, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, E.; Elizen, R.; Vermaas, D.A.; Saakes, M.; Nijmeijer, K. Performance-determining membrane properties in reverse electrodialysis. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 446, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Choi, I. Unveiling the adsorption mechanism of organic foulants on anion exchange membrane in reverse electrodialysis using electrochemical methods. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2023, 53, 1043–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.; Koo, J.; Nam, S.; Kim, E.; Hwang, T.-M. Comparative evaluation of osmotically-driven cleaning methods for organic-inorganic fouling in pressure retarded osmosis (PRO). Eng. Sci. Technol. 2018, 21, 1018–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilli, A.; Cath, T.Y.; Childress, A.E. Power generation with pressure retarded osmosis: An experimental and theoretical investigation. J. Membr. Sci. 2009, 343, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, D.; Lv, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhu, X. Enhancement of power density and hydrogen productivity of the reverse electrodialysis process by optimizing the temperature gradient between the working solutions. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498, 155385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Chen, L.; Zhu, L.; Qiu, Y. Effects of operating parameters and ion characters on the adsorption capacity and energy consumption in membrane capacitive deionization. Desalination Water Treat. 2018, 108, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Porada, S.; Biesheuvel, P.; Van der Wal, A. Energy consumption in membrane capacitive deionization for different water recoveries and flow rates, and comparison with reverse osmosis. Desalination 2013, 330, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Baune, M.; Stolte, S. Separation of organic ions from aqueous solutions by membrane capacitive deionization. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2023, 280, 119012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Zeev, E.; Perreault, F.; Straub, A.P.; Elimelech, M. Impaired performance of pressure-retarded osmosis due to irreversible biofouling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 13050–13058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Choi, Y.; Lee, S.; Park, Y.-G. Comparison of different pretreatment methods for pressure retarded osmosis (PRO) membrane in bench-scale and pilot-scale systems. Desalination 2020, 496, 114528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.-F.; Jang, Y.; Ham, S.-Y.; Ryoo, H.; Park, H.-D. Effects of reverse solute diffusion on membrane biofouling in pressure-retarded osmosis processes. Desalination 2021, 512, 115145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, C.; Liu, S.; Hu, Q.; Zhu, L.; Cao, C. Investigation of the long-term desalination performance of membrane capacitive deionization at the presence of organic foulants. Chemosphere 2018, 193, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Vazquez-Rodriguez, I.; Santos, C.; Garcia-Quismondo, E.; Palma, J.; Anderson, M.A.; Lado, J.J. Graphite felt 3D framework composites as an easy to scale capacitive deionization electrode for brackish water desalination. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 392, 123698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wu, L.; Ma, J.; Wang, M.; Sun, J.; Waite, T.D. Evaluation of long-term performance of a continuously operated flow-electrode CDI system for salt removal from brackish waters. Water Res. 2020, 173, 115580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghamrawi, A.; Saad, M.; Mougharbel, I. Maximum salt adsorption tracking in capacitive deionization cell powered by photovoltaic solar panel. Desalination 2023, 566, 116906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Fang, L.; Qu, H.; Zhou, T.; Chen, C.; Wei, Q.; Kang Shen, P.; Wan, L.; Qun Tian, Z. A wave-powered capacitive deionization system with in-situ blue energy harvester. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498, 155530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Unit | Conditions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TOC | mg/L | 49.6 | |

| UV-254 | cm−1 | 0.30 | |

| SS | mg/L | 17.7 | |

| pH | - | 8 | |

| Electric conductivity | μS/cm | 5250 | |

| Cations | Na+ | mg/L | 706.5 |

| K+ | 108.3 | ||

| Ca2+ | 339.6 | ||

| Mg2+ | 37.6 | ||

| Anions | F− | 6.8 | |

| Cl− | 941.2 | ||

| SO42− | 1269.3 | ||

| NO3− | 58.2 | ||

| Material | Standard | Specification | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrode | Activated Carbon, Graphite | W 100 × L 100 × T 0.6 mm3 | Capacity: >16 mg/g (2000 mg/L as NaCl, 0.1 mL/cm2∙min) 0.1 g/cm3 | |

| Ion exchange membrane 1 | CEM | Polyethylene | W 100 × L 100 × T 0.015 mm3 | Capacity: >1.6 meq/g (Sheet resistance: <0.5 Ω cm2) |

| AEM | Capacity: >1.7 meq/g (Sheet resistance: <0.3 Ω cm2) | |||

| Spacer | Polyethylene terephthalate | W 110 × L 110 × T 0.1 mm3 | Mesh opening: 0.2 mm Tread diameter: 0.055 mm Mesh count: 99 mesh/inch | |

| Conditions | Unit | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacture | - | CMS-PRO-4 (Toray, Seoul, Republic of Korea) |

| Water permeability, A | L/m2·h·bar | 1.97 |

| Salt (NaCl) permeability, B | L/m2·h | 0.619 |

| Structural parameter, S | μm | 713 |

| Conditions | Values | |

|---|---|---|

| Membrane type | Thin-film composite (TFC) PRO membrane | |

| Effective membrane area | 0.145 m) | |

| Membrane orientation | AL-DS (PRO mode) | |

| Flow rate | Feed solution | 0.5 L/min |

| Draw solution | 1.0 L/min | |

| Initial volume | Feed solution | 2 L |

| Draw solution | 4 L | |

| Manufacture | Material | Thickness | Area Resistance | Perm Selectivity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IEMs | CEM | Fujifilm (Type-1), Tilburg, The Netherlands | polyolefin | 135 μm | 2.7 Ω·cm2 | 92 |

| AEM | 125 μm | 1.3 Ω·cm2 | ||||

| Spacer | DS mesh, Seoul, Republic of Korea | 100 μm (mesh with 81.3% open area) | ||||

| Gasket | Tommy hecco, Seoul, Republic of Korea | PTFE | 100 μm | |||

| Specifications | Values |

|---|---|

| Area of one membrane | 0.0196 m2 (14 cm × 14 cm) |

| Membrane pairs | 20 pairs |

| Intermembrane distance | 100 μm |

| Electrode rinse solution | [Fe(CN)6]3−/[Fe(CN)6]4− 50 mM |

| Initial volume | 1 L (both HC, LC) |

| Parameters | Unit | Values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Notation | MCDI 10 | MCDI 30 | MCDI 50 | ||

| Flow rate | mL/min | 10 | 30 | 50 | |

| Feed solution | BWRO brine (refer to Table 1) | ||||

| Cell pairs | Stack | 20 | |||

| Area of one membrane | cm2 | 100 | |||

| Electric potential | V | ±1.5 | |||

| Cycle | Charge/Discharge | s | 300 | ||

| Rest | 10 | ||||

| Operation time | h | over 5 | |||

| Parameters | Values | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure (bar) | 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | |

| Feed Solution | Type | Deionized water | |||||

| Flow rate Cross-flow velocity | 0.5 L/min 23 cm/s | ||||||

| Volume | 2 L | ||||||

| Draw Solution | Type | NaCl 1.2 M (70,200 mg/L) | |||||

| Flow rate Cross-flow velocity | 1.0 L/min 11.5 cm/s | ||||||

| Volume | 4 L | ||||||

| Parameters | Values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure (bar) | 15 | ||||

| Feed Solution | Type | BWRO brine | MCDI 10 | MCDI 30 | MCDI 50 |

| Flow rate Cross-flow velocity | 0.5 L/min 23 cm/s | ||||

| Volume | 2 L | ||||

| Draw Solution | Type | NaCl 1.2 M (70,200 mg/L) | |||

| Flow rate Cross-flow velocity | 1.0 L/min 11.5 cm/s | ||||

| Volume | 4 L | ||||

| Parameters | Values | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low TDS Solution | Type | DI water | |||||||||

| Volume | 1 L | ||||||||||

| High TDS Solution | Type | NaCl 1.2 M (70,200 mg/L) | |||||||||

| Volume | 1 L | ||||||||||

| Flow rate (mL/min) Cross-flow velocity (cm/s) | 10 0.12 | 20 0.24 | 30 0.36 | 40 0.48 | 50 0.60 | 60 0.71 | 70 0.83 | 80 0.95 | 90 1.07 | 100 1.19 | |

| EDS flow rate | 10 mL/min | ||||||||||

| Cell pairs | 10 stacks | ||||||||||

| Parameters | Values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low TDS Solution | Type | BWRO brine | MCDI 10 | MCDI 30 | MCDI 50 |

| Volume | 1 L | ||||

| High TDS Solution | Type | NaCl 1.2 M (70,200 mg/L) | |||

| Volume | 1 L | ||||

| Flow rate Cross-flow velocity | 10 mL/min 0.12 cm/s | ||||

| EDS flow rate | 10 mL/min | ||||

| Cell pairs | 10 stacks | ||||

| Operation time | 5 h | ||||

| Parameters | Unit | BWRO Brine | MCDI 10 | MCDI 30 | MCDI 50 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a 1 | a | b 1 | a | b | a | b | ||

| % | % | % | ||||||

| TOC | mg/L | 49.6 | 10.5 | 78.8 | 11.6 | 76.6 | 13.3 | 73.2 |

| UV-254 | cm−1 | 0.30 | 0.07 | 76.7 | 0.07 | 76.7 | 0.08 | 73.3 |

| SS | mg/L | 17.7 | 3.7 | 79.1 | 4 | 77.4 | 5 | 71.8 |

| Electric conductivity | μS/cm | 5250 | 589 | 88.8 | 979 | 81.4 | 1602 | 69.5 |

| Parameters | Unit | BWRO Brine | MCDI 10 | MCDI 30 | MCDI 50 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a 1 | a | b 1 | a | b | a | b | |||

| % | % | % | |||||||

| Cations | Na+ | mg/L | 706.5 | 123.6 | 82.5 | 155.3 | 78.0 | 165.0 | 76.6 |

| K+ | 108.3 | 15.6 | 85.6 | 23.1 | 78.7 | 23.9 | 77.9 | ||

| Ca2+ | 339.6 | 35.2 | 89.6 | 68.6 | 79.8 | 74.4 | 78.1 | ||

| Mg2+ | 37.6 | 4.3 | 88.6 | 8.4 | 77.7 | 8.9 | 76.3 | ||

| Anions 2 | F− | 6.8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Cl− | 941.2 | 99.5 | 89.4 | 124.8 | 86.7 | 263.3 | 72.0 | ||

| SO42− | 1269.3 | 194.3 | 84.7 | 225.8 | 82.2 | 331.1 | 73.9 | ||

| NO3− | 58.2 | 8.3 | 85.7 | - | - | 16.4 | 71.8 | ||

| CHC | NaCl 1.2 M | |

|---|---|---|

| Flow Rate | ||

| 10 mL/min | 1.78 | |

| 20 mL/min | 1.91 | |

| 30 mL/min | 1.90 | |

| 40 mL/min | 1.95 | |

| 50 mL/min | 1.92 | |

| 60 mL/min | 1.97 | |

| 70 mL/min | 1.93 | |

| 80 mL/min | 1.97 | |

| 90 mL/min | 1.93 | |

| 100 mL/min | 1.95 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.; Lee, J.; Ju, J.; Cho, H.; Choi, Y.; Lee, S. Application of Membrane Capacitive Deionization as Pretreatment Strategy for Enhancing Salinity Gradient Power Generation. Membranes 2025, 15, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15020056

Lee S, Lee J, Ju J, Cho H, Choi Y, Lee S. Application of Membrane Capacitive Deionization as Pretreatment Strategy for Enhancing Salinity Gradient Power Generation. Membranes. 2025; 15(2):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15020056

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Seoyeon, Juyoung Lee, Jaehyun Ju, Hyeongrak Cho, Yongjun Choi, and Sangho Lee. 2025. "Application of Membrane Capacitive Deionization as Pretreatment Strategy for Enhancing Salinity Gradient Power Generation" Membranes 15, no. 2: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15020056

APA StyleLee, S., Lee, J., Ju, J., Cho, H., Choi, Y., & Lee, S. (2025). Application of Membrane Capacitive Deionization as Pretreatment Strategy for Enhancing Salinity Gradient Power Generation. Membranes, 15(2), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15020056