Gas Separation Silica Membranes Prepared by Chemical Vapor Deposition of Methyl-Substituted Silanes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Membrane Synthesis

2.2. Membrane Permeance Tests

2.3. Membrane Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

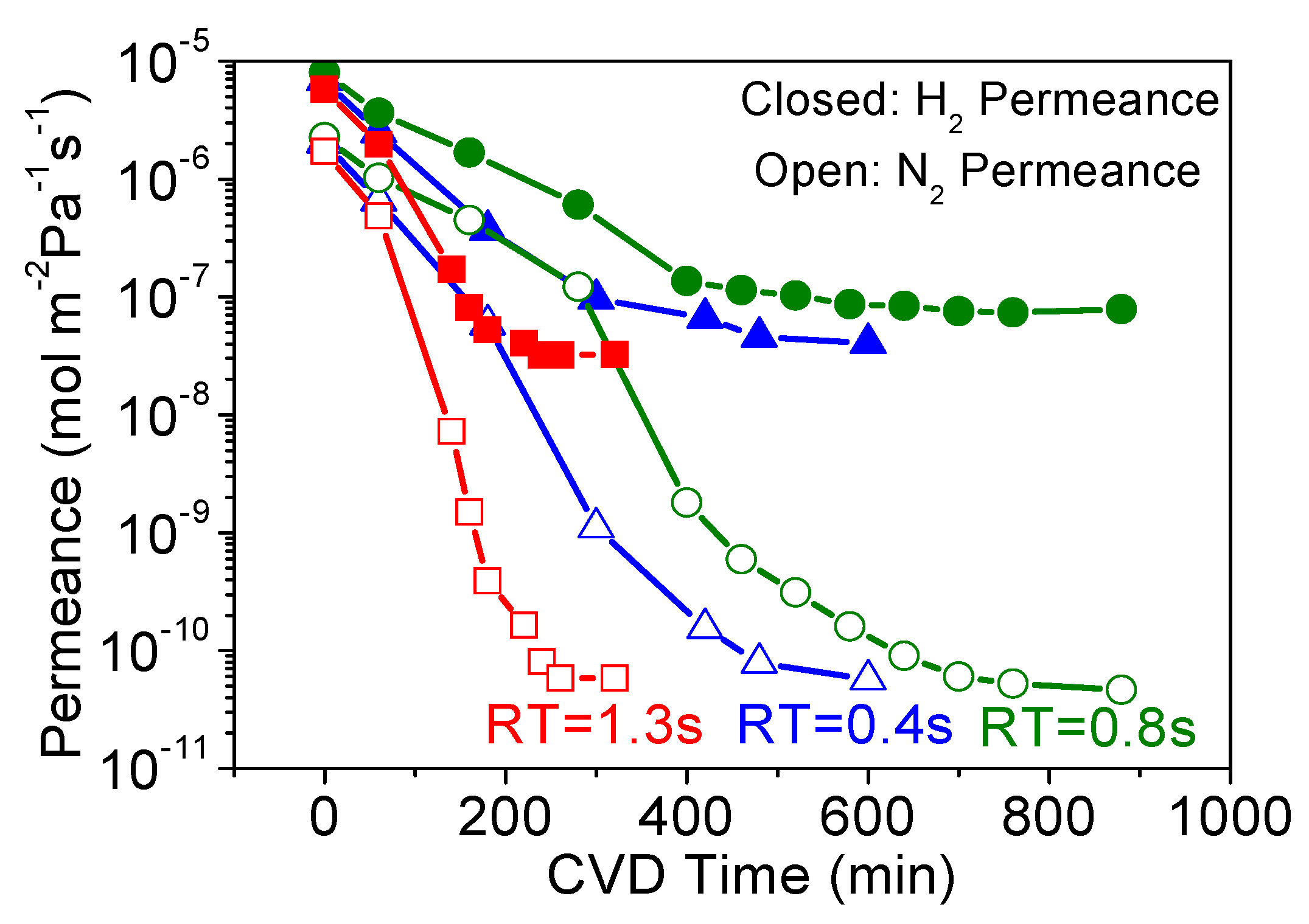

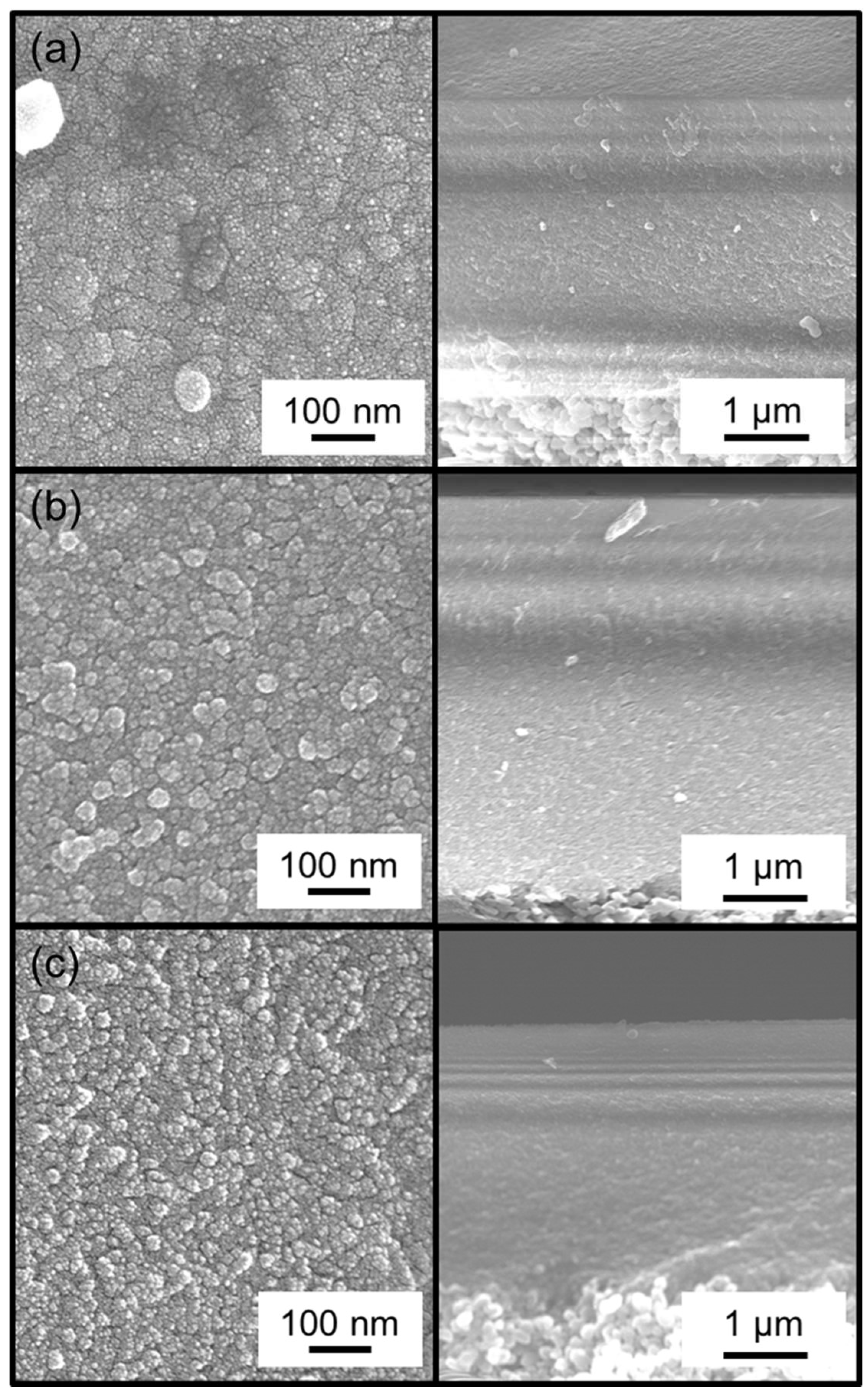

3.1. Effect of Precursor Residence Time in CVD

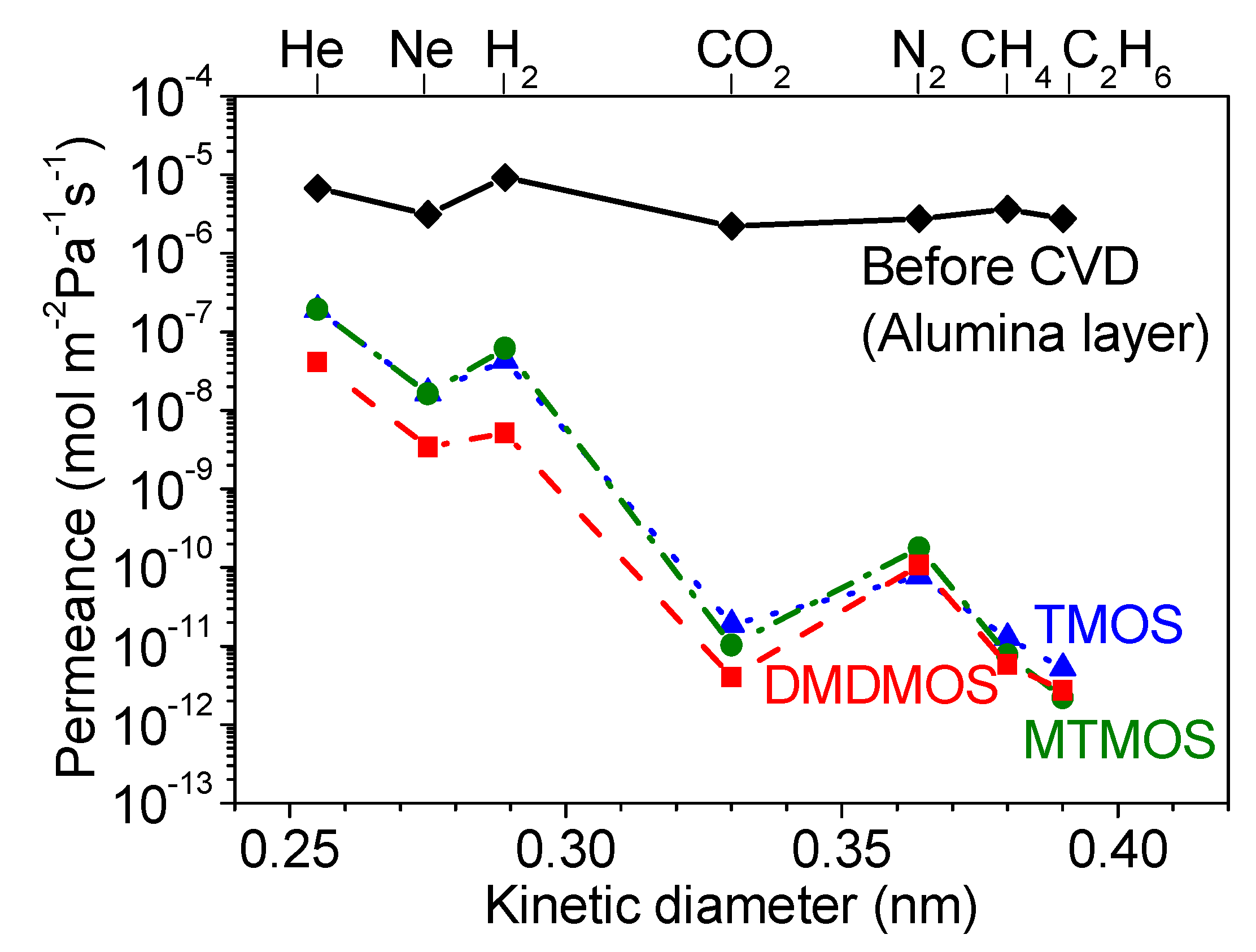

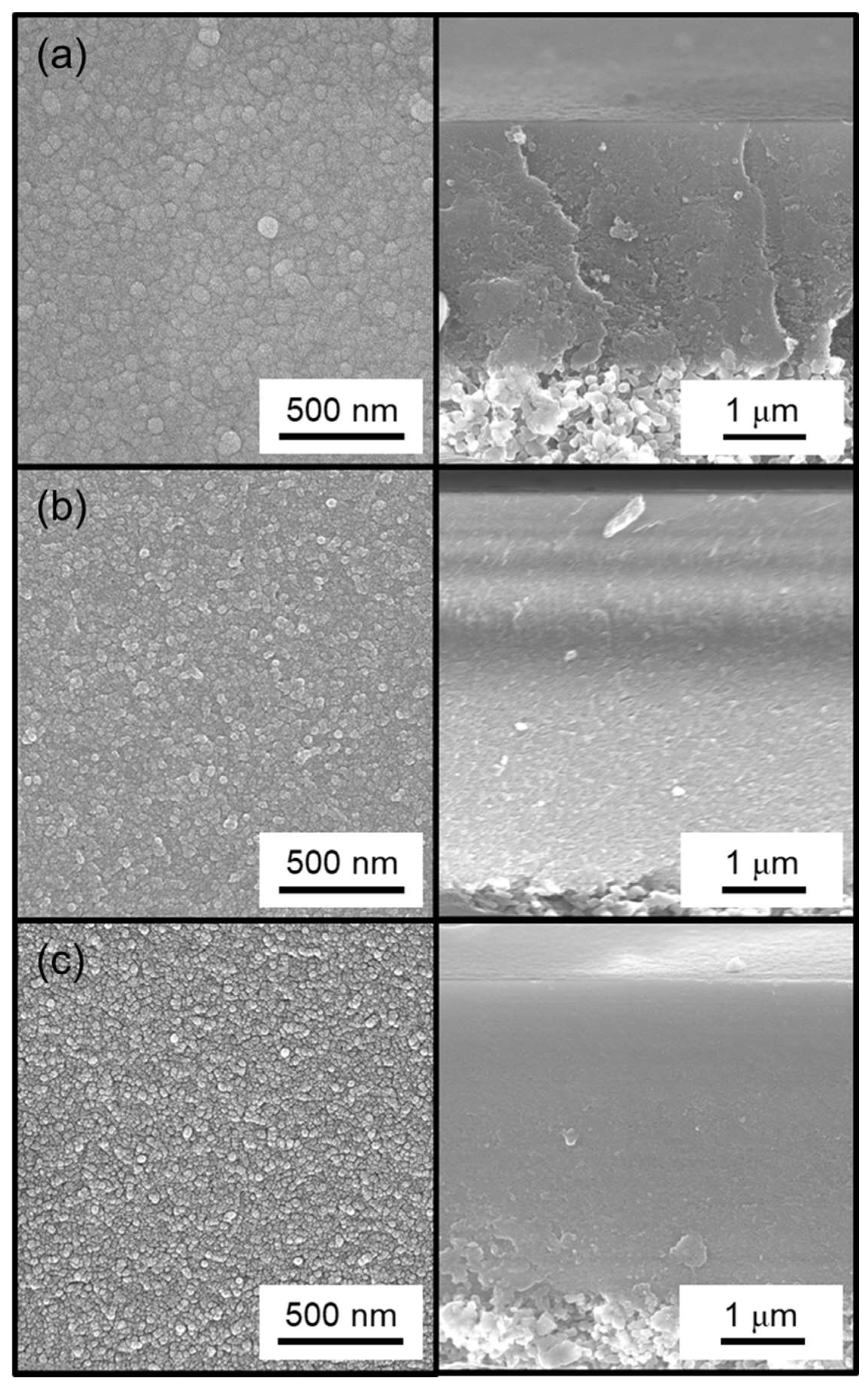

3.2. Effect of Methyl-Substituted Methoxysilanes

3.3. FTIR Spectroscopy

3.4. Hydrothermal Stability Test

3.5. Gas Diffusion Mechanism Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khatib, S.J.; Oyama, S.T. Silica membranes for hydrogen separation prepared by chemical vapor deposition (CVD). Sep. Purif. Technol. 2013, 111, 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, S.T.; Yamada, M.; Sugawara, T.; Takagaki, A.; Kikuchi, R. Review on mechanisms of gas permeation through inorganic membranes. J. Jpn. Pet. Inst. 2011, 54, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, T.; Inoue, H. Introduction of specific gas selectivity to porous glass membranes by treatment with tetraethoxysilane. J. Membr. Sci. 1989, 42, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Oyama, S.T. Correlations in palladium membranes for hydrogen separation: A review. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 375, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, M.; Matsuyama, E.; Ikeda, A.; Komatsuzaki, M.; Sasaki, M. Preparation of silica hybrid membranes for high temperature CO2 separation. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 2014, 47, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaoud, S.B.; Takagaki, A.; Sugawara, T.; Kikuchi, R.; Oyama, S.T. Alkylamine–silica hybrid membranes for carbon dioxide/methane separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 477, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Messaoud, S.B.; Takagaki, A.; Sugawara, T.; Kikuchi, R.; Oyama, S.T. Development of inorganic-organic hybrid membranes for carbon dioxide/methane separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 471, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.W. Membrane Technology and Applications, 3rd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Basile, A. Handbook of Membrane Reactors, 1st ed.; Woodhead Publishing, Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Basile, A.; Gallucci, F. Membranes for Membrane Reactors: Preparation, Optimization and Selection; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Yang, W. Perspective: Molecular sieve membranes: From 3D zeolites to 2D MOFs. Chin. J. Catal. 2015, 36, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, T.; Sato, K. Degradation mechanism of an H2-permselective amorphous silica membrane. J. Mater. Sci. 2014, 49, 4115–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, H.; Minamizawa, T.; Kanezashi, M.; Yoshioka, T.; Tsuru, T. Microporous organosilica membranes for gas separation prepared via PECVD using different O/Si ratio precursors. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 489, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akamatsu, K.; Suzuki, M.; Nakao, A.; Nakao, S. Development of hydrogen-selective dimethoxydimethylsilane-derived silica membranes with thin active separation layer by chemical vapor deposition. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 580, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, M.; Nagayo, T.; Monma, K. Pore size control of a molecular sieve silica membrane prepared by a counter diffusion CVD method. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 2007, 40, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Feky, H.H.; Briceno, K.; Jardimc, E.O.; Silvestre-Albero, J.; Gumí, T. Novel silica membrane material for molecular sieve applications. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2013, 179, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuyama, E.; Ikeda, A.; Komatsuzaki, M.; Sasaki, M.; Nomura, M. High-temperature propylene/propane separation through silica hybrid membranes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2014, 128, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.F.; Vaezian, B.; Khatib, S.J.; Oyama, S.T.; Wang, Z.X.; Achenie, L. Hybrid H2-selective silica membranes prepared by chemical vapor deposition. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2012, 47, 1698–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, Y.; Akamatsu, K.; Sugawara, T.; Nakao, A.; Miyoshi, A.; Nakao, S. Development of pore size-controlled silica membranes for gas separation by chemical vapor deposition. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 315, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sea, B.K.; Kusakabe, K.; Morooka, S. Pore size control and gas permeation kinetics of silica membranes by pyrolysis of phenyl-substituted ethoxysilanes with cross-flow through a porous support wall. J. Membr. Sci. 1997, 130, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, S.; Okabe, A.; Ogawa, A.; Gondo, D.; Imasaka, S.; Hasegawa, Y.; Sato, K.; Li, K.; Yamamoto, H. Preparation and pervaporation performance of vinyl-functionalized silica membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 548, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.-J.; Yun, G.-N.; Takagaki, A.; Kikuchi, R.; Oyama, S.T. Synthesis and characterization of hydrogen selective silica membranes prepared by chemical vapor deposition of vinyltriethoxysilane. J. Membr. Sci 2018, 550, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niimi, T.; Nagasawa, H.; Kanezashi, M.; Yoshioka, T.; Ito, K.; Tsuru, T. Preparation of BTESE-derived organosilica membranes for catalytic membrane reactors of methylcyclohexane dehydrogenation. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 455, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Gong, G.H.; Kanezashi, M.; Yoshioka, T.; Ito, K.; Tsuru, T. Pervaporation performance and characterization of organosilica membranes with a tuned pore size by solid-phase HCl post-treatment. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 441, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castricum, H.L.; Sah, A.; Kreiter, R.; Blank, D.H.A.; Vente, J.F.; Elshof, J.E.T. Hybrid ceramic nanosieves: Stabilizing nanopores with organic links. Chem. Commun. 2008, 9, 1103–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castricum, H.L.; Sah, A.; Kreiter, R.; Blank, D.H.A.; Vente, J.F.; Elshof, J.E.T. Hydrothermally stable molecular separation membranes from organically linked silica. J. Mater. Chem. 2008, 18, 2150–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshimo, M.; Saito, T.; Akamatsu, K.; Segawa, A.; Nakao, S. Influence of toluene vapor on the H2-selective performance of dimethoxydiphenylsilane-derived silica membranes prepared by the chemical vapor deposition method. J. Membr. Sci. 2012, 415, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshimo, M.; Akamatsu, K.; Furuta, S.; Nakao, S. H2 Purification Durability of Dimethoxydiphenylsilane-Derived Silica Membranes with H2–Toluene Mixtures. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 17257–17262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshimo, M.; Akamatsu, K.; Furuta, S.; Nakao, S. Comparative study on the influence of toluene and methylcyclohexane on the performance of dimethoxydiphenylsilane-derived silica membranes prepared by chemical vapor deposition. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2015, 140, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akamatsu, K.; Tago, T.; Seshimo, M.; Nakao, S. Long-termstable H2 production from methylcyclohexane using a membrane reactor with a dimethoxydiphenylsilane-derived silica membrane prepared via chemical vapor deposition. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54, 3996–4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-L.; Yamada, H.; Saito, T.; Kai, T.; Murakami, K.; Nakashima, M.; Ohshita, J.; Akamatsu, K.; Nakao, S.-I. Development of hydrogen-selective triphenylmethoxysilane-derived silica membranes with tailored pore size by chemical vapor deposition. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 499, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-L.; Akamatsu, K.; Nakao, S. Hydrogen separation in hydrogen–methylcyclohexane–toluene gaseous mixtures through triphenylmethoxysilane-derived silica membranes prepared by chemical vapor deposition. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55, 5395–5402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, M.; Nishi, Y.; Utsumi, T.S.K.; Nakamura, R. Preparation of thin Li4SiO4 membranes by using a CVD method. Energy Procedia 2013, 37, 1012–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Oyama, S.T. Ultrathin, hydrogen-selective silica membranes deposited on alumina-graded structures prepared from size-controlled boehmite sols. J. Membr. Sci. 2007, 306, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Hacarlioglu, P.; Oyama, S.T. Hydrothermally stable silica–alumina composite membranes for hydrogen separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 310, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Wei, J. Diffusion mechanism of hydrocarbons in zeolites—I. Theory. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1992, 47, 1123–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cussler, E.L. Diffusion: Mass Transfer in Fluid Systems; Cambridge University Press, 2009; pp. 190–191. [Google Scholar]

- Wakao, N. Gas Diffusion in Pores. Chem. Eng. 1964, 28, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chihara, K.; Suzuki, M.; Kawazoe, K. Review on Mechanism of Surface Diffusion and Intracrystalline Diffusion in Adsorbent Particles in Gaseous Phase: Part (1) Surface Diffusion. Mon. J. Inst. Ind. Sci. Univ. Tokyo 1977, 29, 195–267. [Google Scholar]

- Oyama, S.T.; Lee, D.; Hacarlioglu, P.; Saraf, R.F. Theory of hydrogen permeability in nonporous silica membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2004, 244, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Oyama, S.T. High molecular permeance in a poreless ceramic membrane. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 1636–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacarlioglu, P.; Lee, D.; Gibbs, G.V.; Oyama, S.T. Activation energies for permeation of He and H2 through silica membranes: An ab initio calculation study. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 313, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milella, A.; Palumbo, F.; Delattre, J.L.; Fracassi, F.; d’Agostino, R. Deposition and characterization of dielectric thin films from allyltrimethylsilane glow dischanges. Plasma Process. Polym. 2007, 4, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelby, J.E. Molecular diffusion solubility of hydrogen isotopes in vitreous silica. J. Appl. Phys. 1977, 48, 3387–3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackelford, J.F.; Studt, P.L.; Fulrath, R.M. Solubility of gases in glass. Part II. He, Ne, and H2 in fused silica. J. Appl. Phys. 1972, 43, 1619–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.W.; Frank, R.C.; Swets, D.W. Diffusion of hydrogen and deuterium in fused quarts. J. Chem. Phys. 1962, 36, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.W. Diffusion of hydrogen in natural and synthetic fused quarts. J. Chem. Phys. 1963, 38, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelby, J.E. Helium migration in natural and synthetic vitreous silica. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1972, 55, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

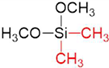

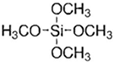

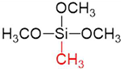

| Silica Precursor | Tetramethyl Orthosilicate (TMOS) | Methyltrimethoxysilane (MTMOS) | Dimethyldimethoxysilane (DMDMOS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical structure |  |  |  |

| Vapor pressure (atm) (25 °C) | 0.023 | 0.051 | 0.12 |

| Membrane | H2 Permeance | N2 Permeance | H2/N2 Selectivity | CVD Time | Precursor Flow Rate | Total Precursor Flowed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mol∙m−2∙s−1∙Pa−1) | (–) | (min) | (μmol∙s−1) | (mmol) | ||

| RT = 0.4 s | 1.12 × 10−8 | 5.3 × 10−11 | 210 | 600 | 0.46 | 17 |

| RT = 0.8 s | 1.14 × 10−8 | 2.9 × 10−11 | 400 | 880 | 0.23 | 12 |

| RT = 1.3 s | 6.8 × 10−9 | 6.9 × 10−11 | 99 | 320 | 0.15 | 2.9 |

| Precursor | Study | H2 Permeance (mol∙m−2∙s−1∙Pa−1)(600 °C) | H2/N2 Selectivity (–) (600 °C) |

|---|---|---|---|

TMOS | Nomura et al. | 2 × 10−7 | 610 |

| This work | 1.7 × 10−7 | 990 | |

MTMOS | Nomura et al. | 3 × 10−7 | 590 |

| This work | 2.4 × 10−7 | 740 | |

DMDMOS | Nomura et al. | 9 × 10−7 | 920 |

| This work | 4.4 × 10−8 | 410 |

| TMOS | MTMOS | DMDMOS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H2 Permeance | −64% | −46% | −34% |

| N2 Permeance | −32% | −20% | −44% |

| H2/N2 Selectivity | −47% | −32% | +19% |

| TMOS | MTMOS | DMDMOS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jumping distance, d (nm) | 0.75 | 0.79 | 0.72 |

| Number of solubility sites, NS (1025 m−3) | 7.3 | 9.7 | 0.75 |

| Vibration frequency, v (1012 s−1) | 1.9 | 1.8 | 0.68 |

| Activation energy, ΔE (kJ∙mol−1) | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.9 |

| Regression coefficient, R2 (–) | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.995 |

| Silica Precursor | Gas | Constant, C (mol∙m−2∙s−1∙Pa−1∙K−1/2) | Activation Energy, ∆Ea (kJ∙mol−1) | Regression Coefficient, R2 (–) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMOS | CO2 | 1.2 × 10−7 | 26 | 0.997 |

| N2 | 3.5 × 10−8 | 15 | 0.955 | |

| MTMOS | CO2 | 2.8 × 10−7 | 35 | 0.981 |

| N2 | 1.6 × 10−7 | 21 | 0.998 | |

| CH4 | 7.4 × 10−10 | 7.9 | 0.999 | |

| DMDMOS | CO2 | 4.7 × 10−9 | 19 | 0.975 |

| N2 | 1.4 × 10−8 | 8.3 | 0.991 | |

| CH4 | 2.0 × 10−10 | 1.3 | 0.991 |

| Silica Precursor | Gas | Kinetic Diameter (nm) | (mol∙m−2∙s−1∙Pa−1) | −∆Ha −∆Ea (kJ∙mol−1) | Regression Coefficient, R2 (–) | Enthalpy of Vaporization, ∆Hvap (kJ∙mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMOS | CH4 | 0.38 | 2.9 × 10−12 | 7.3 | 0.990 | 8.2 |

| DMDMOS | CH4 | 0.38 | 4.4 × 10−12 | 1.7 | 0.990 | 8.2 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kato, H.; Lundin, S.-T.B.; Ahn, S.-J.; Takagaki, A.; Kikuchi, R.; Oyama, S.T. Gas Separation Silica Membranes Prepared by Chemical Vapor Deposition of Methyl-Substituted Silanes. Membranes 2019, 9, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes9110144

Kato H, Lundin S-TB, Ahn S-J, Takagaki A, Kikuchi R, Oyama ST. Gas Separation Silica Membranes Prepared by Chemical Vapor Deposition of Methyl-Substituted Silanes. Membranes. 2019; 9(11):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes9110144

Chicago/Turabian StyleKato, Harumi, Sean-Thomas B. Lundin, So-Jin Ahn, Atsushi Takagaki, Ryuji Kikuchi, and S. Ted Oyama. 2019. "Gas Separation Silica Membranes Prepared by Chemical Vapor Deposition of Methyl-Substituted Silanes" Membranes 9, no. 11: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes9110144

APA StyleKato, H., Lundin, S.-T. B., Ahn, S.-J., Takagaki, A., Kikuchi, R., & Oyama, S. T. (2019). Gas Separation Silica Membranes Prepared by Chemical Vapor Deposition of Methyl-Substituted Silanes. Membranes, 9(11), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes9110144