In-Situ Experimental Study of Closed-Diaphragm Wall Foundations for Cross-Sea Suspension Bridges

Abstract

1. Introduction

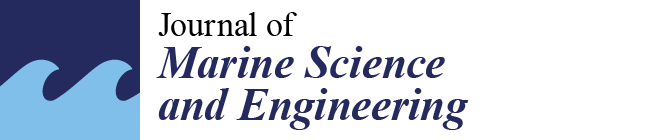

2. Geotechnical Profile and Method of Construction

2.1. Geotechnical Profile

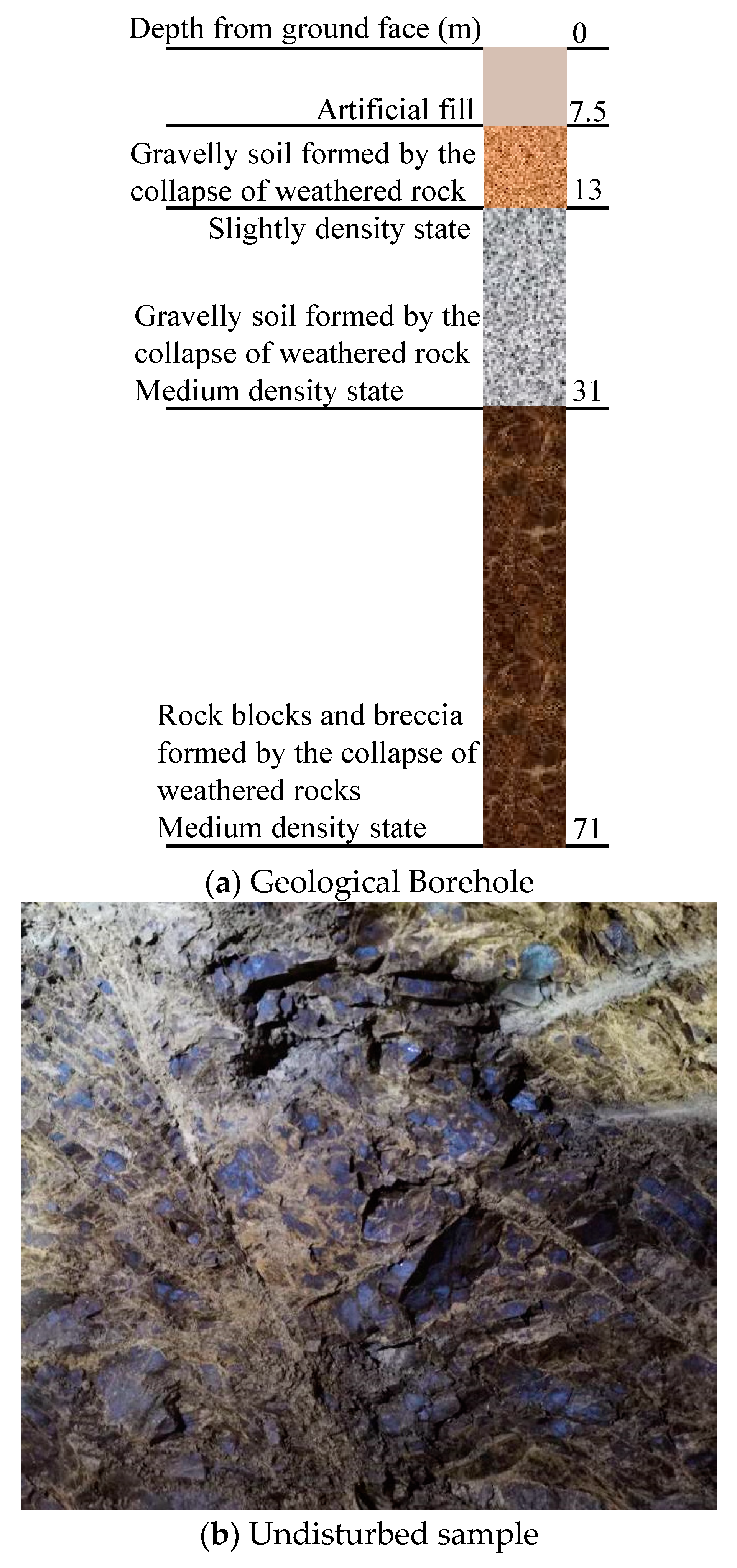

2.2. Method of Construction

3. Lateral Load Test

4. Test Result and Analysis

4.1. Load–Displacement Response

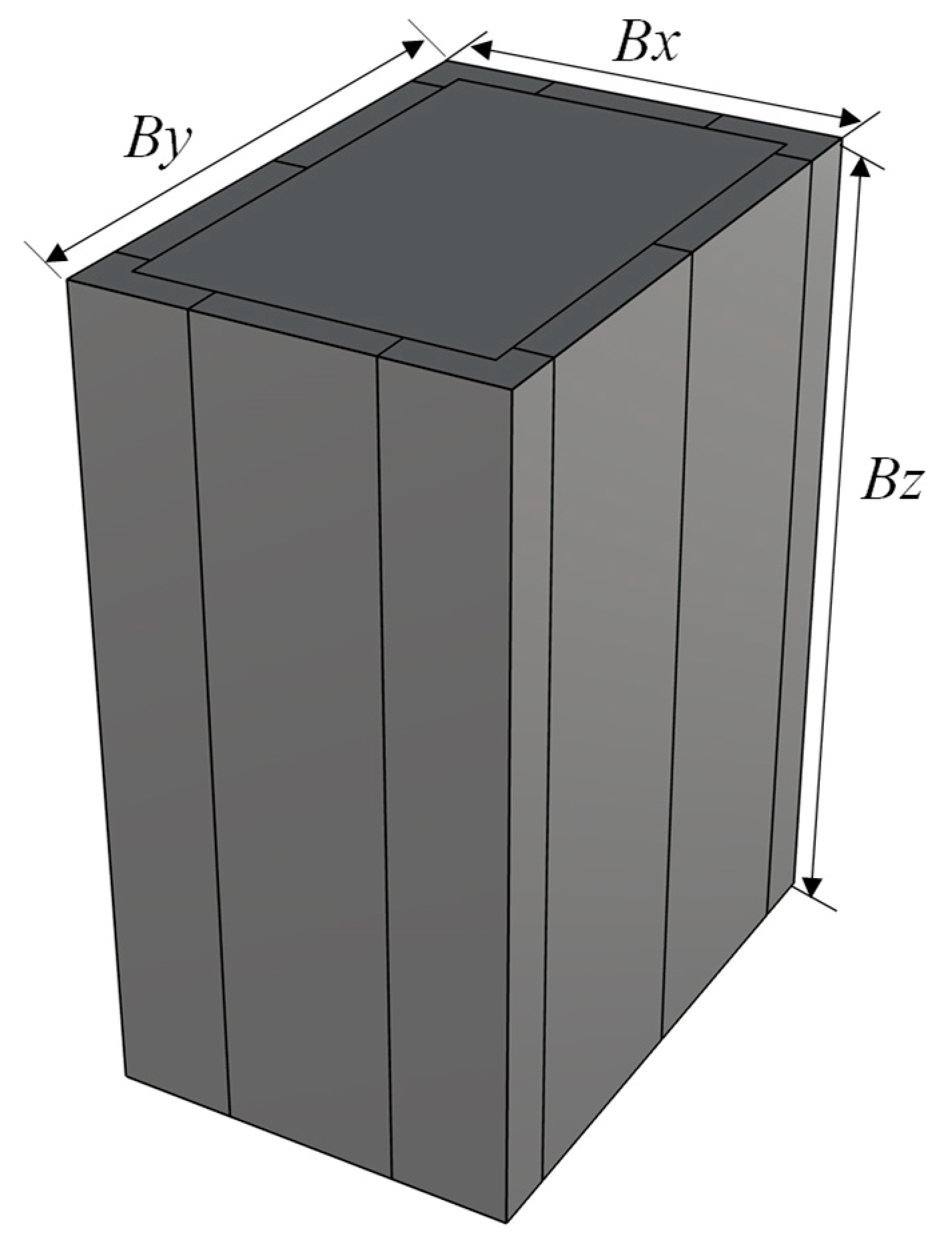

4.2. Lateral Displacement

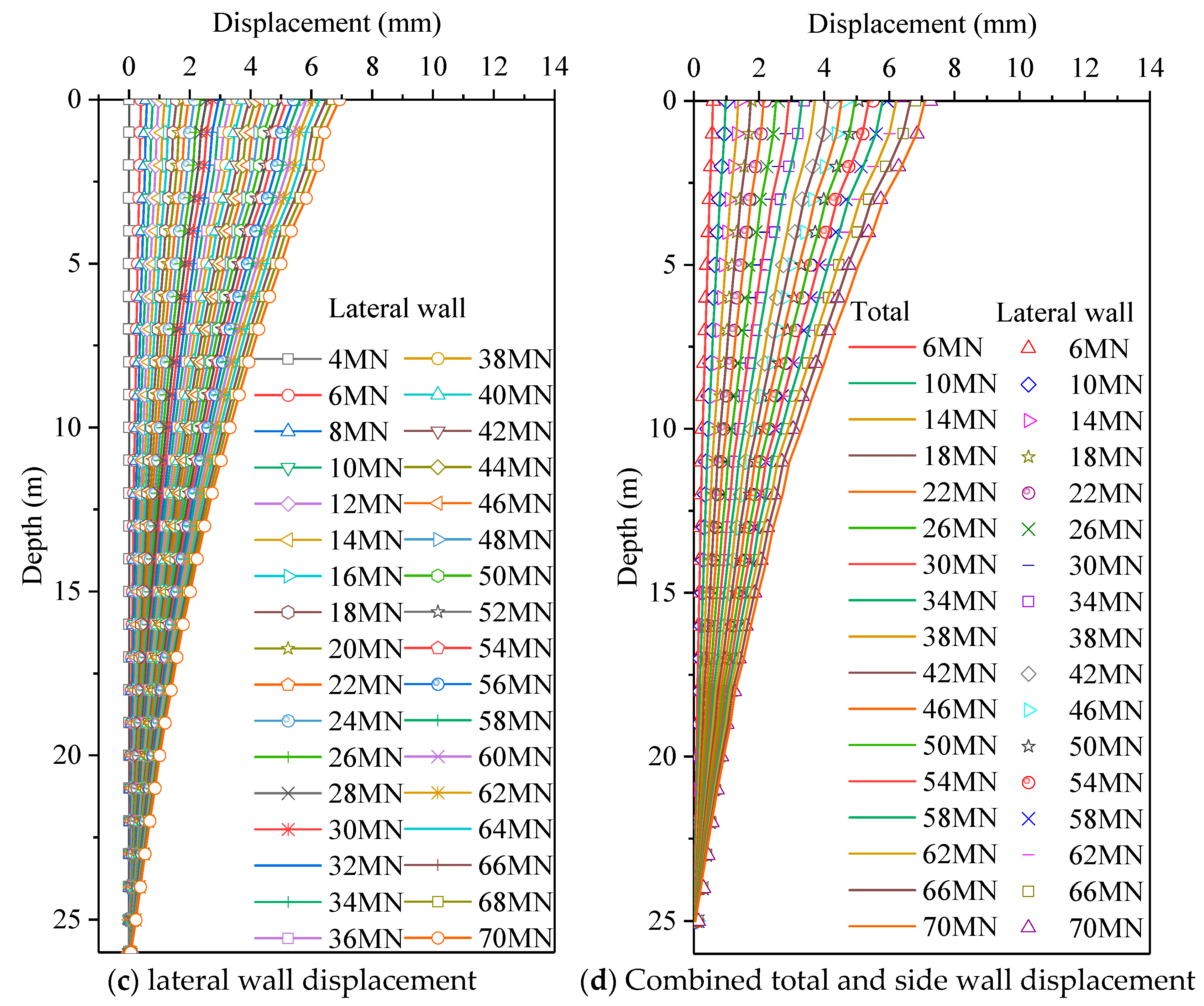

4.3. Vertical Displacement

4.4. Earth Pressure

5. Discussion

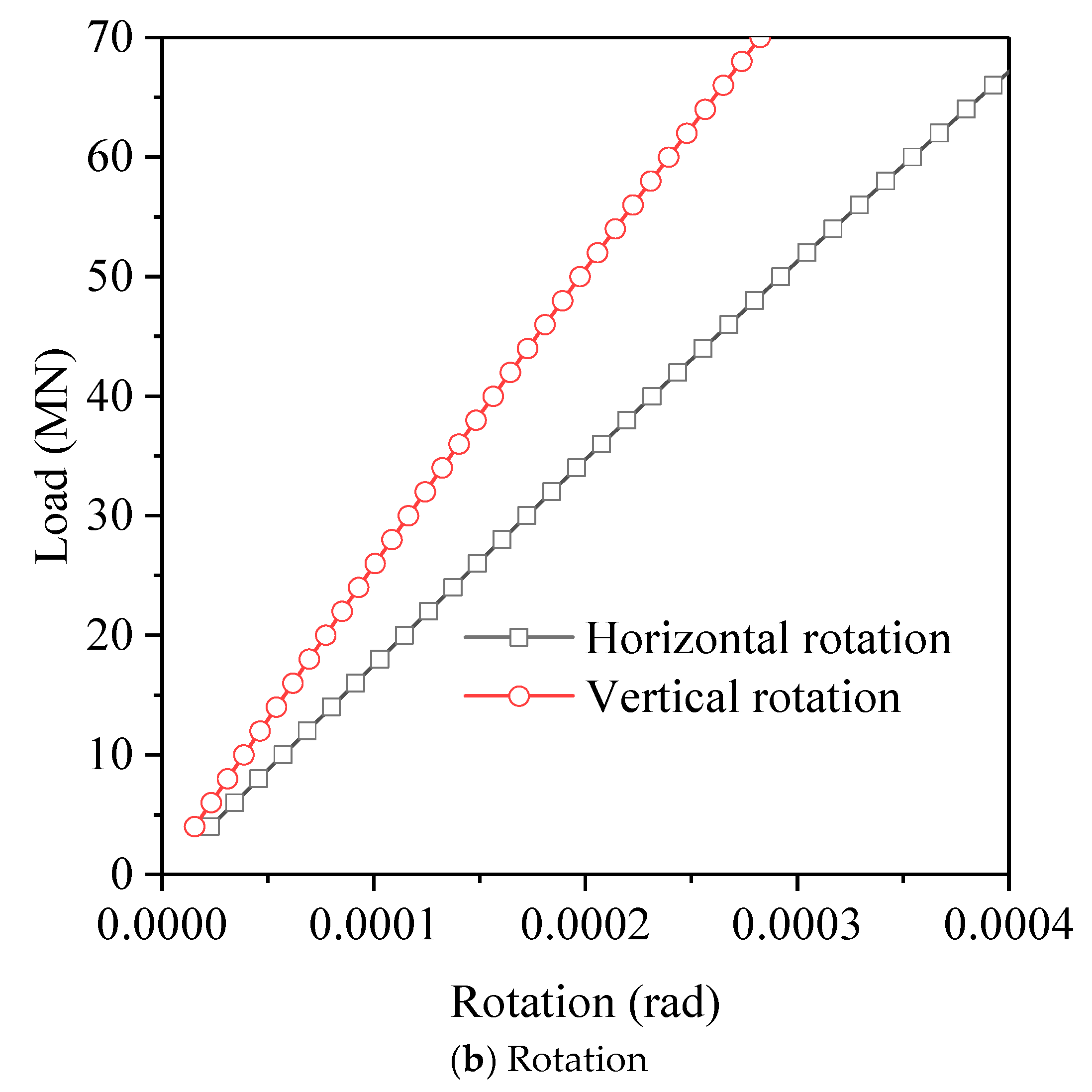

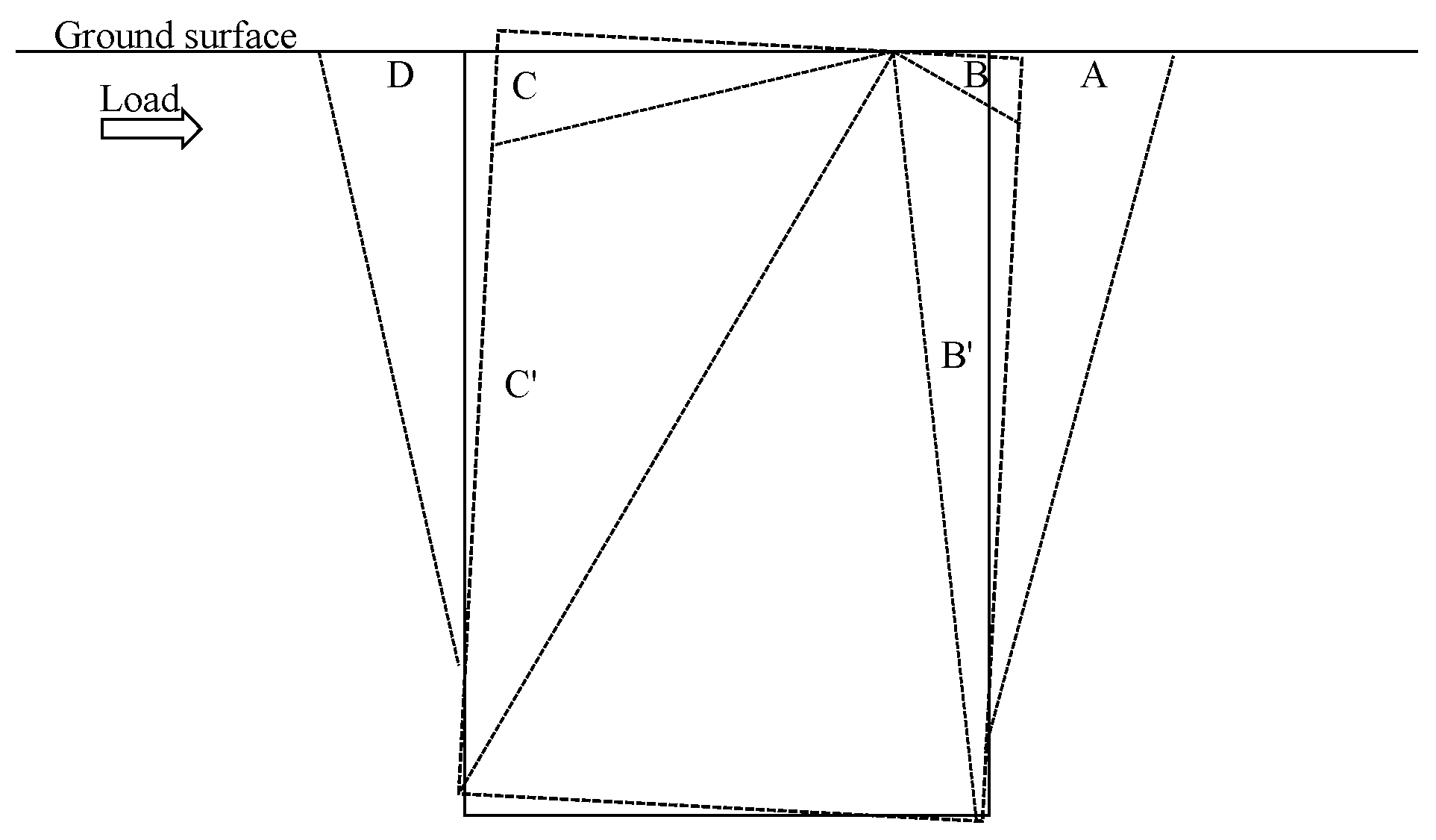

5.1. Motion State

5.2. Soil–Foundation Interaction

6. Conclusions

- The closed-diaphragm wall exhibits an initially linear, but increasingly nonlinear load–displacement response as the horizontal load increases. The horizontal displacement of the lateral walls closely mirrors the overall displacement of the diaphragm wall, making it a reliable indicator of the closed wall’s load state, especially in cases where it is difficult to measure total displacement.

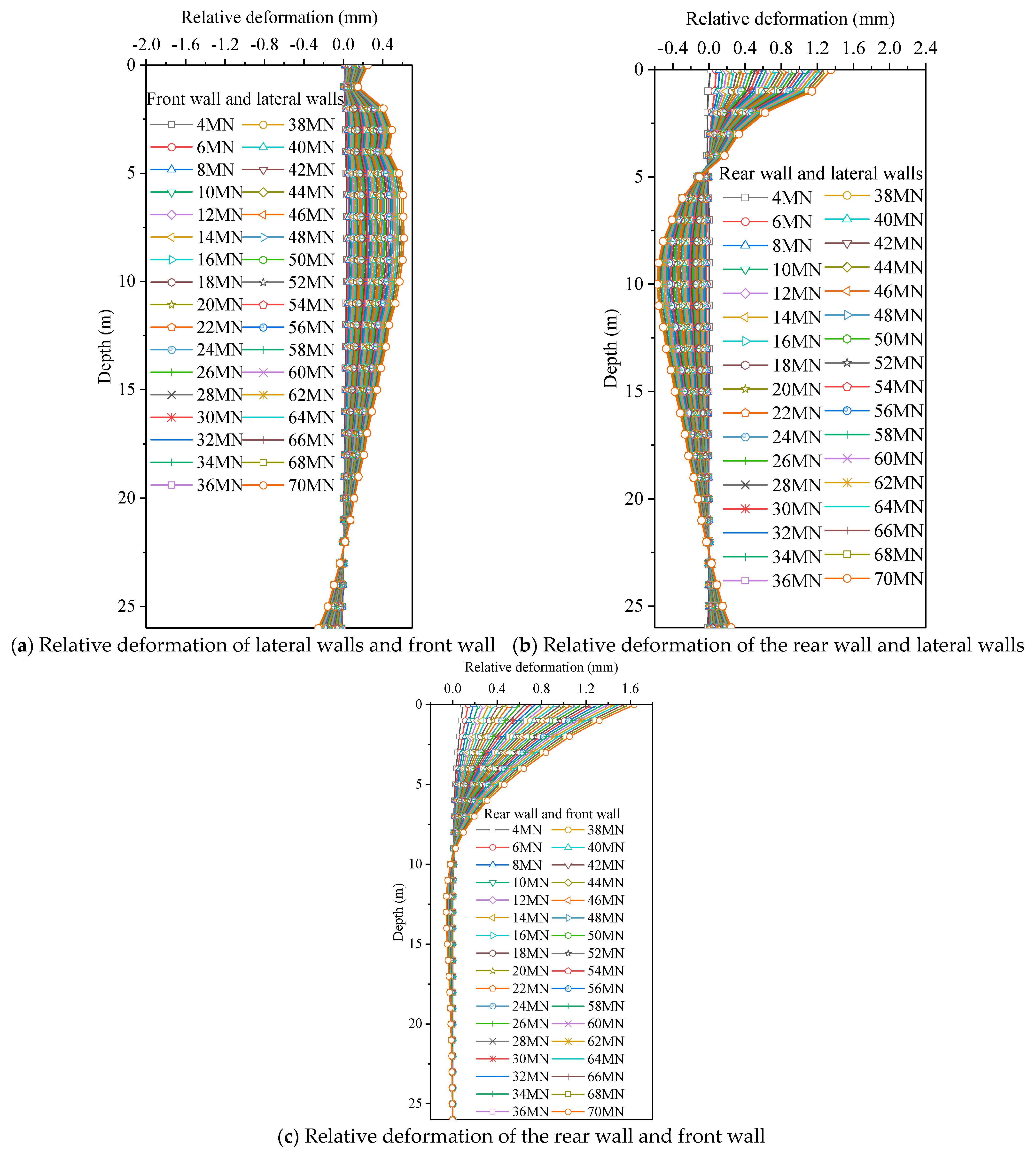

- The closed-diaphragm wall exhibits rigid-body deformation characteristics under horizontal loading, with minimal relative displacement between sections or components. Its primary failure mode is tilting, emphasizing the importance of considering rotational effects in its design. The rotation point varies, with horizontal variation ranging from 0.24 By to 0.58 By and vertical variation ranging from 0.67 Bz to 0.7 Bz.

- Earth pressure around the closed-diaphragm wall varies, as follows: at the front edge, both inner and outer soils experience passive earth pressure. At the rear edge, the upper soil is under active pressure, while the lower soil is subjected to passive pressure. This differential soil behavior is critical for ensuring the stability and resistance of the foundation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaino, T. Closed wall foundation of reinforced concrete. Concr. J. 1984, 22, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ebrahimipour, A.; Eslami, A. Analytical study of piles behavior for marine challenging substructures. Ocean Eng. 2024, 292, 116514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohari, K.; Kishi, N.; Matsuoka, K.; Nishimoto, S. Static analysis of a continuous underground deep wall under construction of the main tower foundation of Hakuchō Ōhashi. J. Struct. Constr. Eng. 1996, 1996, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, T.; Wada, T.; Tamaki, H. Shiratori Ōhashi shuta kiso ni kansuru: Chichū renzoku kabe no sekkei to seisō [Regarding the main tower foundation of Shiratori Ōhashi—Design and construction of the underground continuous wall]. In Proceedings of the Heisei Gannen Gijutsu Kenkyū Happyōkai [Heisei First Year Technical Research Presentation], Hokkaido, Japan, 1990; Volume 1990, pp. 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai, K.; Takahashi, M.; Abe, Y. A Report of Methods for the Structural Analysis of High Depth Slurry Wall Supporting the Main Tower of a Suspension Bridge. Doboku Gakkai Ronbunshu 1994, 1994, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Petroski, H. Engineering: Akashi Kaikyo Bridge. Am. Sci. 2009, 97, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makoto, K. Technology of the Akashi Kaikyo bridge. J. Struct. Control. Health Monit. 2004, 11, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashima, S.; Sano, Y.; Furuya, N.; Yamaoka, R. Design and construction of ultra thick underground wall for an anchorage of Akashi-Kaikyo bridge. Doboku Gakkai Ronbunshu 1992, 1992, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Furuya, N.; Tatsumi, M.; Saito, T.; Yamaoka, R.; Sakimoto, J.; Ito, M. Results of observation and simulation of deep excavation for the foundation 1A anchorage of Akashi-Kaikyo Bridge. Doboku Gakkai Ronbunshu 1993, 1993, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Kim, S.C.; Seo, Y.H.; Kim, J.H. The Yi Sun-Sin bridge: Innovative solutions for suspension bridges. Struct. Eng. Int. 2012, 22, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, I.K.; Kim, K.T.; Seo, Y.H. The Design and Construction of the Anchorage of Yi Sun-Sin Grand Bridge. In Proceedings of the Korean Geotechical Society Conference, Korean Geotechnical Society, Jinju-si, Republic of Korea, 25–26 March 2010; pp. 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lyngs, J.H.; Kasper, T.; Bertelsen, K.S. Modelling of soil-structure interaction for seismic analyses of the Izmit Bay Bridge. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, Paris, France, 2–6 September 2013; pp. 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Foged, B.; Steenfelt, J.S.; Augustesen, A.H. Geotechnical design of the Izmit Bay Suspension Bridge. IABSE Symp. Rep. 2015, 104, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, T.; Yanagihara, M.; Yamasaki, Y.; Ozturk, A.N.; Zeybek, F. Izmit Bay Suspension Bridge-Overview of the Project. IABSE Madr. Symp. Rep. 2014, 102, 2081–2088. [Google Scholar]

- Avar, B.B.; Augustesen, A.H.; Kasper, T.; Steenfelt, J.S.; Foged, B. Geotechnical verification of the south anchor block of the Izmit Bay Suspension Bridge in Turkey. In Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Soil Mechanics and Ge-otechnical Engineering: Geotechnical Engineering for Infrastructure and Development, Edinburgh, UK, 15 March 2016; ICE Publishing: London, UK; pp. 713–718. [Google Scholar]

- Löhning, T.; Ravn, U.G.; Pedersen, F.; Westh, L.; Christoffersen, M. The 1915 Çanakkale Bridge–Design and Con-struction of Substructure. In Proceedings of the IABSE Symposium: Long Span Bridges, Istanbul, Turkey, 26–28 April 2023; pp. 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güzel, Ö. 1915 Çanakkale Bridge—Dream to reality. In Building for the Future: Durable, Sustainable, Resilient; Ilki, A., Çavunt, D., Çavunt, Y.S., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Volume 349, pp. 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JGJ 106-2014; Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. Technical Code for Testing of Building Foundation Piles. China Architecture Building Press: Beijing, China, 2014.

- JTG/T 3512-2020; Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. Technical Specification for Foundation Piles Testing of Highway Engineering. People’s Transport Press: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Cheng, Q.; Wu, J.; Song, Z.; Wen, H. The behavior of a rectangular closed diaphragm wall when used as a bridge foundation. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2012, 6, 398–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, W.; Tao, Q.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Gong, W.; Dai, G. In-Situ Experimental Study of Closed-Diaphragm Wall Foundations for Cross-Sea Suspension Bridges. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2304. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse12122304

Li W, Tao Q, Li C, Wang X, Gong W, Dai G. In-Situ Experimental Study of Closed-Diaphragm Wall Foundations for Cross-Sea Suspension Bridges. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2024; 12(12):2304. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse12122304

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Wenshuai, Qiyu Tao, Chao Li, Xin Wang, Weiming Gong, and Guoliang Dai. 2024. "In-Situ Experimental Study of Closed-Diaphragm Wall Foundations for Cross-Sea Suspension Bridges" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 12, no. 12: 2304. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse12122304

APA StyleLi, W., Tao, Q., Li, C., Wang, X., Gong, W., & Dai, G. (2024). In-Situ Experimental Study of Closed-Diaphragm Wall Foundations for Cross-Sea Suspension Bridges. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 12(12), 2304. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse12122304