1. Introduction

The coastal zones are the interface between continents and oceans and are areas of great ecological, social, and economic importance, which include terrestrial systems such as beaches and dunes, and aquatic systems such as coastal lagoons and estuaries [

1]. They also harbor some of the world’s most productive ecosystems, such as mangrove forests, marshes, coral reefs, and sea grass [

2]. These ecosystems, as a result of their locations, serve as pollutant filters that prevent pollutants from reaching the ocean in high concentrations [

3]. The attributes of these ecosystems make them attractive for the development of socioeconomic activities, such as port development, tourism, aquaculture, and fishing [

4], which has led to inappropriate use and exploitation, coupled with a lack of adequate regulations and non-compliance with established standards [

5]. In addition, it is known that over 50% of the world’s population inhabits urban settlements in coastal zones, contributing wastewater discharges to aquatic systems, causing land use changes, and increasing the production of organic and inorganic wastes [

6,

7]. This has caused ecological issues in some places, including loss of diversity, eutrophication, disruption of successional processes, and extinction of species, among others [

8,

9].

A key element in coastal areas are beach–dune systems, a dynamic deposit of sediments, which besides serving as shields for the coast from hydro meteorological events [

10] are also highly appealing destinations for tourism [

11]. In Mexico, according to the World Travel and Tourism Council [

12], tourism profits exceeded US

$209BN (17% of GDP) in 2018, with beach destinations receiving more than 75% of tourists [

13]. Given its importance, it becomes essential to implement strategies for the integral assessment of tourism development and the environmental condition of beaches, considering sectorial and economic environmental policies, as recommended by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) [

14,

15]. In this sense, within the conceptual framework of pressure–state–response (PSR), human activities exert pressures on the environment that change the status (i.e., quality and quantity) of natural resources, triggering a social response through public policies [

16,

17]. Based on the PSR model, the European Environment Agency (EEA) adopted the driving forces–pressure–state–impact–response (DPSIR) model at the end of the 1990s, which is based on changes in the state and impact of a system, as measured through indicators, setting the grounds for informed decision making [

18].

A number of coastal management indicators have been used to evaluate the main environmental, social, economic, and political aspects; these indicators quantify, synthesize, and convey information in order to facilitate and contribute to the decision making process [

17,

19,

20]. In addition, indicators should be relevant, simple, available, reproducible, and comparable; additionally, these should clearly show the status, trend, and exchange rates of ecosystem services to facilitate decision-making [

21]. The driving force indicators used in coastal areas include vegetation cover, land occupation by infrastructure, uses, services, and social aspects, such as the type of tourism, intensity of use, current sanitary facilities, areas occupied by umbrellas, number of beach restaurants (“ramadas”), and parking lots. [

22]. This information facilitates identifying on-site anthropic activities that cause social, environmental, and economic changes [

23]. Additionally, the socio environmental perception of beach users has been considered as an indicator for the evaluation of activities that act as beach pressures, taking into account cleaning (litter), water quality, and safety [

10].

The trophic index (TRIX) [

24] evaluates the trophic status of marine systems, as determined from four variables related to primary production—chlorophyll-a, dissolved oxygen, dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN), and dissolved inorganic phosphorus (DIP) concentrations—covering oligotrophic to eutrophic conditions. Any indicators considered for impact assessment should reflect environmental changes, such as loss of biodiversity, presence of pathogens and diseases, public health, and economic deterioration [

22]. Finally, the framework of the DPSIR model considers the design of response actions according to the driving forces, the state conditions, and the identification of pressures in the system studied [

25].

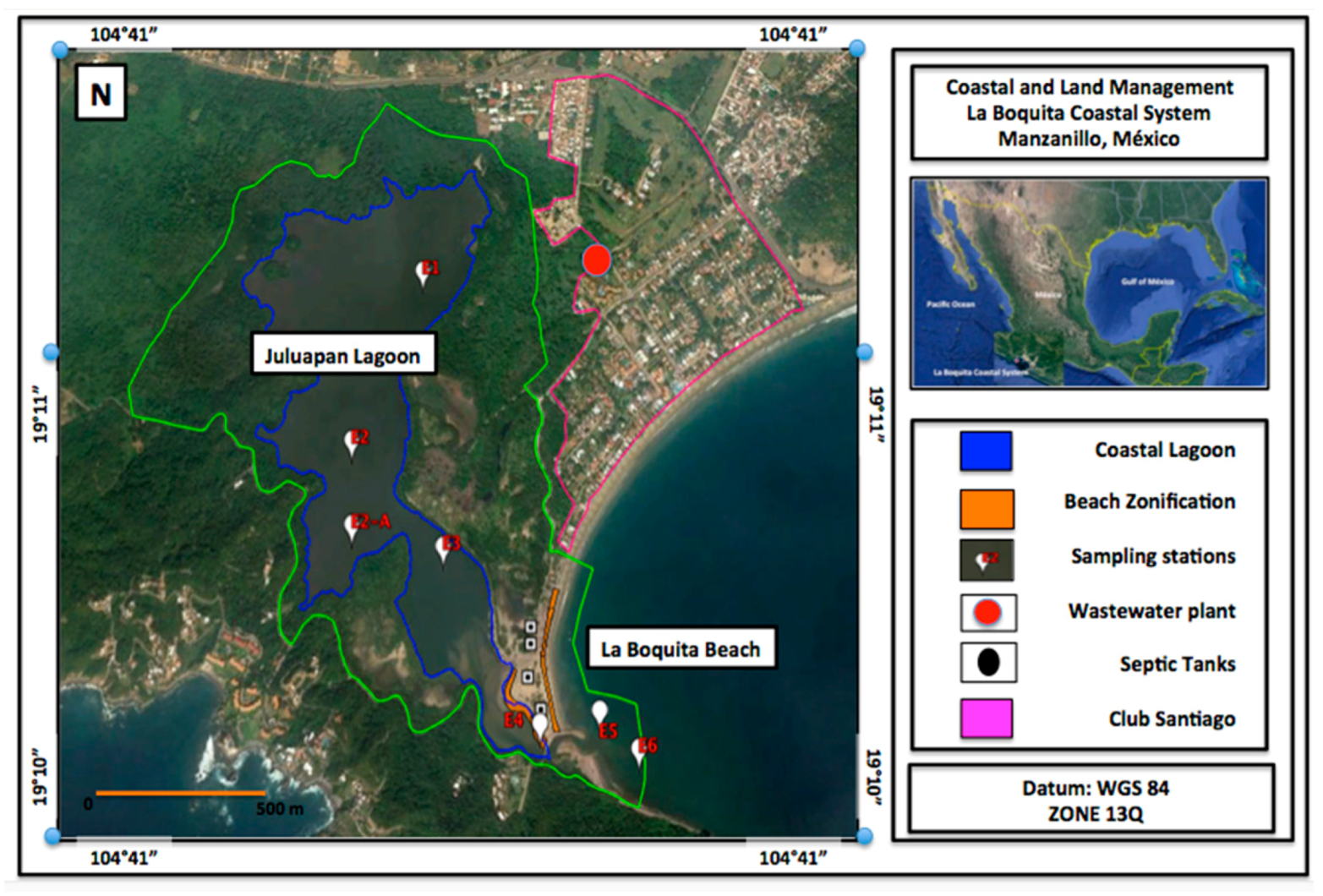

According to the number of tourists, Manzanillo, México, ranks tenth as a tourist destination in Mexico, with over 500,000 tourists per year [

13]. In this tourism destination, La Boquita Beach and Juluapan Lagoon (La Boquita coastal system, LBCS) are the main beaches in terms of beach space occupation and carrying capacity, based on the excessive demand for umbrellas and food services during the seasons of peak tourist affluence [

26]. However, despite its importance, it lacks coastal planning and management. In this work, the La Boquita coastal system was evaluated with the DPSIR model, based on the analysis of driving force, pressure, and state indicators. The final outcome (response) is intended to be used for decision making in coastal management strategy and land use planning.

4. Discussion

Sun, sea, and sand (SSS) tourist destinations attract a large influx of visitors and represent a major source of income for the economies of some countries, including Mexico, which in 2016 represented 12.45% of its gross domestic product [

13,

46,

47,

48]. This work shows that the increase in tourism is a clear driver, as evidenced by the almost 400% increase in land use for tourism over the past 15 years and the increase in the BDU in holiday periods (see photographs in

Appendix A). As a result, the environmental deterioration and lack of planning have raised concerns about the future of LBCS, similar to other attractive destinations [

49]. Therefore, the use and analysis of indicators and the use of tools to identify pressures are essential for the design and adoption of coastal management strategies for development that ensure competitiveness, sustainability, and conservation [

50]. In the LBCS, tourism is the main driver of changes in the state of the environment, both on the beach area and in the adjacent aquatic systems, mainly due to increased pressures. One example is wastewater discharges from the residential tourist settlement Club Santiago through the Miramar treatment plant, reaching the adjacent ocean through its communication channel. These discharges affect the beach and the adjacent reef area due to the load of suspended solids and the high N and P levels from the interior of the lagoon, causing the whiteness of the coral and a 30% decrease in its abundance [

51,

52]. According to the analysis carried out in this study, this unfavorable trend will continue in the near future if no mitigation measures are taken and the current regulations are not enforced.

The identification of appropriate indicators to measure the issues at each tourist destination or recreational settlement is fundamental—these can be quantitative (e.g., BDU) and qualitative (e.g., user perception) [

53]. The occupation of space, represented in this study by the number of umbrellas and the BDU, is an indicator that is extensively used to determine socioecological pressures, which may effectively identify the deterioration of tourist destinations [

54]. In this regard, setting an ideal carrying capacity is complex, as this will depend on each locality, beach type, and user perceptions.

The classification of NC 93-06-302 was used to analyze the BDU; this revealed moderate-to-intensive beach use (3.8–10 m

2/user) in three of the four areas, mainly over the holiday periods. Similarly, using the classification of the carrying capacity proposed by Botero-Saltarén et al. [

28], we determined an intensive carrying capacity (<10 m

2/user) during holiday periods in most cases. The above is in agreement with the perceptions of users, who mostly noticed a medium-to-high saturation of the beach; however, users were mostly repeat visitors (i.e., they had visited the area previously) who felt safe and noticed that the water and beaches were clean, thus perceiving a feeling of comfort. According to the Yepes classification [

55], a beach condition is considered comfortable at densities above 4 m

2/user, which are consistent with the densities observed in this study. Similar to the BDU values, the numbers of umbrellas rose substantially during holiday periods, a situation that had already been detected in a previous study, where umbrellas in the LBCS resting areas were considered to occupy more than 50% of the beach. This is considered unfavorable for environmental and aesthetic quality reasons [

26].

Undoubtedly, the space use indicators show significant increases during the peak tourist seasons in the LBCS. Although this is not perceived by users as a negative factor, other indicators should be considered to establish the carrying capacity of the system, taking into account the different stages of the life cycle of the tourist destination [

49]. In general, users of LBCS were apparently more interested in leisure-related infrastructure and services than in water quality and biodiversity, a finding that has been previously reported elsewhere [

56]. This indicates a lack of knowledge or ignorance about coastal ecosystems, as well as the poor environmental education and communication of these topics across society.

Although the perceptions of users are considered in the development of management programs and proposals during decision making [

57], overestimating this indicator may lead to a mistaken underestimation of coastal management strategies, thus threatening environmental health. Additionally, it should be mentioned that the LBCS is a system that has been modified by the construction of access roads and “ramadas” to provide tourist services to visitors in public beaches used for recreation, given their accessibility and proximity to urban areas. According to NC-93-06-302, these characteristics should also be taken into account in the occupation and use of sandy beach space.

Excessive occupation puts pressure on the soil, which can result in compaction of sediments, thus affecting sandy substrates. As part of this project, a study conducted during the 2016 Easter holidays in the LBCS to analyze the diversity index in the beach area showed that benthic macrofauna was virtually absent in most of the area sampled, a finding suggesting potential ecological issues associated with space occupation in these areas. According to the analysis of the regulations [

58,

59,

60] relating to the occupation of spaces, they set rules for human settlements aiming to preserve and restore ecological balance and protect the environment through the use, exploitation, inspection, and surveillance of beaches. However, poor implementation practices (law enforcement) have led to environmental degradation in the LB system, showing a downward trend in compliance. Besides, no plan is currently in place for the restoration of the affected areas, as would be required in accordance with these regulations.

The increased space occupation changes the state of the system, as in the cases of the production of solid wastes and wastewater discharges, which in some cases may not be regulated, adding pollutants that affect the trophic state, as well as pathogens [

61]. The factors mentioned above are used as indicators to assess the state of the system. Coastal water bodies are exposed to fecal contamination, which is mainly associated with recreational activities, wastewater discharges, cattle raising, deforestation, and other factors; thus, concentrations of

Enterococcus and fecal coliforms are the most suitable indicators for detecting fecal pollution in water [

62]. According to the World Health Organization, the concentration range of

Enterococcus in seawater suitable for recreational use is between 0 and 200 MPN/100 mL. In this study, we reported a temporal variation, with low

Enterococcus levels during pre-holiday periods that do not entail public health risks; however, one of the major concerns in the LBCS is the limited availability of public restrooms for users, as well as the lack of adequate treatment plants for wastewater discharges in the region. According to our analysis, the future trends regarding these factors are not favorable, as the Mexican Technical Standard (NMX-AA-120-SCFI-2016) indicates that the study area must comply with the bacteriological quality limit of 100 MPN/10 mL. This is important, because a previous study in La Boquita [

63] showed that during the season of peak tourist activity, the concentrations of these bacteria exceeded 2000 MPN/100 mL.

However, the samples from the relevant monitoring office are collected during pre-holiday periods, when the concentration is within allowable limits, while our analysis during the peak tourist season revealed that the allowed limit for

Enterococcus was exceeded, as mentioned above. The lack of control over wastewater discharges into the lagoon has also been identified. Additionally, the presence of larva migrans (Ancylostomatidae) in the sand of the LB system beach has been reported, as well as cases of parasitized persons since 2010 [

64]. The larva migrans comes from the fecal matter of parasitized animals, which are usually street dogs and cats roaming the area. Larva migrans infections have commonly been documented in travelers visiting mainly tropical and subtropical beaches [

65,

66,

67,

68]. The presence of such parasites may be considered as an indicator of the poor sanitary quality of beaches, which is a potential topic of analysis for future research [

68].

Regarding the lack of control of wastewater discharges into the lagoon, the water quality results for the concentrations of nitrogen, dissolved phosphorus, chlorophyll-a, and dissolved oxygen, as well as their integration in the TRIX index, all suggested eutrophic conditions in some seasons and areas of the Jualuapan Lagoon. During the rainy season (i.e., June, August, and October), chlorophyll a, DIN, DIP, and the TRIX index indicated mesotrophic-to-eutrophic conditions in the inner portions of the lagoon. The innermost area of the Juluapan Lagoon has little water exchange with the adjacent sea. The salinity values suggest that this is the area showing the longest residence time, a condition that favors the accumulation of nutrients that lead to high chlorophyll concentrations and the overall deterioration of the system. This is related to the low dissolved oxygen levels reported for April in the interior of the lagoon, which affects the rest of the stations and maybe related to nearby wastewater discharges. A similar condition has also been observed in other systems, such as the Cienfuegos Bay system [

69], and can become intensified during the warmer months (August and October) due to the increased growth of bacteria, and consequently the increase in bioavailable nutrients and phytoplankton productivity. Moreover, continental materials carried in runoff during the rainy season may also contribute to the increase in DIN and DIP levels originating from adjacent tourist areas, which boost primary productivity and promote an eutrophic status in the lagoon.

Environmental degradation associated with tourism is well documented [

70,

71,

72]. However, this work shows that continuous monitoring, scientific analysis, and the use of the DSPIR framework as a planning and management tool are all strictly necessary to determine the carrying capacity of systems; the short-, medium-, and long-term environmental impacts; and preventive and ecological restoration strategies, among others. Likewise, it is essential to communicate the results obtained, as these set the basis and input for decision-makers in the law enforcement of coastal legislation. Tourism cannot be restricted in countries such as Mexico, where the economy largely depends on this industry [

12,

13]; however, it is imperative to reverse the current trends in terms of the pressures on ecosystems. According to the analysis conducted in this study, some actions that should be implemented in the LBCS include the improvement of sanitary services, involving increases in the availability of restrooms and wastewater treatment. This work provides information that points to the deterioration of water quality in the lagoon and the adjacent sea, mainly during the holiday season, since around 65% of the established beach restaurants (“ramadas”) are irregular, showing the poor regulation of the use of land and the occupation of spaces. Therefore, it is essential that the infrastructure for restaurants is improved and that the use of spaces for different activities is defined within the limits of user density.

5. Conclusions

The lack of studies and analysis makes this work a baseline and input for the implementation and improvement of public policies. The implementation of the DPSIR model made it possible to identify the main issues in the region and their root causes, allowing the implementation of coastal management strategies. We identified that the lack of enforcement of environmental regulations leads to tourist activities causing a change of state toward the eutrophication of water and the deterioration of the lagoon environment and its surrounding marine area.

The 396% increase in occupancy and increased carrying capacity compromise the ecosystem services, which are a subset of ecological processes and ecosystem structures that are directly linked to benefits to human well being, as well as the value of the beach as an environmental asset.

Continuous monitoring of changes in land use, tourist pressure, and water quality are suitable indicators of compliance with current regulations, which allow us to propose the improvement of the sanitary infrastructure and the planning of the occupation of space for recreational use, aiming to change the trends related to the pressures that currently threaten the environmental health of the LBCS, in order to preserve and maintain these coastal systems.

The implementation of the DPSIR and the results obtained in this work can be used as inputs for decision making and in the design of environmental strategies for occupation and land use based on sustainable development goals (SDGs)—namely clean water and sanitation (goal 6), sustainable cities and communities (goal 11), and life below water (goal 14) goals—along with coastal law enforcement and ecosystem monitoring, in order to preserve this natural infrastructure and support local economies based on tourism and recreation.

Although it may seem obvious, this work highlights the importance of generating data on the evolution of tourism in a given area to allow the determination of the carrying capacity of a system. This information will contribute to making sure that the local ecological services are not compromised while the activities in this area support the local economy.