1. Introduction

Marine diesel engine trigeneration energy systems (MDETES) represent coupling diesel engine cogeneration systems with absorption cooling systems, which allow the use of a co-generation effect to balance the occurring overall heating loads on marine motor ships intended for the transport of moderately cooled cargoes, [

1]. Modern marine four stroke engines’ energy efficiency rate is in the range of about 49% to 50% at its nominal load, [

2,

3]. Two stroke engines’ energy efficiency is slightly higher, at the gas mode about 53% [

4,

5]; however, on the diesel mode, energy efficiency is lower at about 52%. The calculation for the two-stroke engine is based on the LHV of the MDO 42.7 MJ/kg, and LHV of a typical LNG 48.0 MJ/kg, [

6,

7]. As the marine engines cannot convert all heat energy to power, the remaining exhaust heat energy may be utilized for the boiling process of the absorption cooling unit. The typical process utilization overview was given in [

8,

9]. The exhaust gas heat energy of marine engines [

10,

11] is not the only source of heat energy; waste cooling energy of the marine engines may be utilized for that purpose as well. The waste heat capacity potential of the typical stationery and marine engines is analyzed in [

12,

13], where it is concluded that this part of the energy also has potential for trigeneration purposes. The improvement of the waste heat recovery from marine diesel engines with the best fulfilment of the vessel needs in terms of mechanical, electric and thermal energies is analyzed in [

14,

15], where various solutions are proposed, with combined diesel engine, steam and gas turbines recovering part of the thermal energy of the diesel engine exhaust gas. The similar approach of feedwater regeneration to the boiler from the marine engines was presented in [

16], which also concluded that waste heat will beneficially contribute to the efficiency of waste heat recovery. In marine diesel engine cogeneration energy systems (MDECES), the propulsion of the main diesel engine (MDE) directly or indirectly drives the propeller (P), and the shaft electric generator (SEG), balancing both occurring propulsion and electrical load during the voyage, while the occurring heating load is balanced by the waste heat recovery steam generator (WHRSG). During both maneuver and standstill, the ship’s occurring electric load is balanced by the diesel aggregates (DA), and the resulting heating load of the ship is balanced mainly by the fired steam generator (FSG) due to the insufficient availability of waste heat contained in the exhaust gases of the DA. The overview of the energy balance for the cruise ship and the chemical tanker is given in [

17,

18]. As the vessel is sailing, it is changing the local microclimate’s environmental condition. The engine is not always operating in the steady condition but is changing load, which affects the absorption process. In order to reduce the negative effect on the absorption process, [

19] carried out where proposed a solution to the amortization of the heat load changes with the small diameter tube bundle heat exchangers with large specific surface area. The changes of the local microclimate environment should not always affect the absorption process in the negative direction, according to the study under [

20]; off design performance of the LiBr-H

2O, particularly in the lower generator or higher condenser temperature conditions, generates both higher COP and exergy efficiency. However, in this particular study the absorption process in the complex rolling and pitching environment of the ship is not considered.

Due to economic considerations, the ship’s diesel engines are supplied with cheaper, heavy fuel (HFO, IFO380) [

21,

22]; therefore, the combustion gases must not substantially cool down because of the presence of sulfur oxides in them, which consequently limits the cogeneration plant heating effect. During navigation, unsteadiness of the cogeneration thermal effect is emphasized due to its dependence on emerging propulsion load (which is reflected through fluctuation of power and engine speed) and on the temperature of the surrounding air, which was discussed in [

23,

24,

25]. On the other hand, the heating load of the ship has been determined by its purpose, respectively prescribed microclimate of the contained commodities compartments, and of the navigation route, so that it is continuously changing according to which climate zone the ship is in [

26]. Apart from the need to balance the heating load, it is necessary to create an appropriate cooling effect for balancing the cooling load [

27], which is in almost all modern ships balanced by the compression refrigeration plant (CRP); this significantly increases the electric load, while the heating effect of the installed cogeneration plant is being considerably unexploited [

28]. By the use of an absorption refrigeration unit (ARU) with thermodynamic mixtures of water-lithium bromide (H

2O-LiBr) [

29,

30], and ammonia water (NH

3-H

2O) [

31,

32], and with negligible electrical load, the utilization of the cogeneration thermal output for a production appropriate cooling effect is allowed. The attainable lower temperature limit in the evaporator ammonium ARU (AARU) restricts its application on both accommodation air conditioning systems and commercial cargo that is being transported and stored in a moderate temperature range (−25 to 15 °C). On the other hand, an attainable lower temperature limit in the evaporator lithium bromide ARU (LBARU) restricts its application on the accommodation air conditioning systems. By coupling the DECES and ARU, the (MDETES) is created, which enables cost-effective, energy-efficient, and environmentally friendly balancing of the occurring heating loads of both air conditioning systems and moderate commercial refrigerated cargo by the use of the cogeneration heating effect. Reducing the electrical load automatically reduces the mechanical loads of the MDE during navigation, as well as of the DA during maneuvering and the ship’s standstill in the terminals, which implies substantial fuel savings and consequently lower operating costs with the reduction of the majority of ecologically harmful effects (primarily CO

2 and SO

2 emissions) according to [

33,

34].

This paper continues with efforts in the rational usage of the waste heat from the marine diesel engines. It presents a comprehensive mathematic model of the proposed trigeneration system for reefer use. The concept interrelates the trajectory of a vessel and the wave conditions with a detailed described quasi-static model of the energetic, economic and environmental performance of a marine trigeneration unit installed onboard.

2. Defining Technically Possible Application Fields ARU’s

Technically, the obtainable upper temperature of the absorption chiller cooker is ϑcc ~ 170 °C (which is determined by the parameters of steam from the cogeneration plant), and the cooling sea temperature ϑsd ~ 32 °C. These two parameters determine the applicability of the absorption cooling with ammonia mixture on those cooling systems where the temperature of ammonia primary refrigerator in evaporator does not fall below ϑse ~ −35 °C and considering the usual arrangement of the cooling system with CaCl2 brine as secondary refrigerant, which corresponds to the storage temperature limited at the ϑca ~ −25 °C. Such achievable lower temperature storage facilitates the transporting of a wide range of palletized (packed bulk) and liquid cargo, where the majority of commercial bulk palletized cargos comprise foodstuffs, transporting either frozen (dead) or unfrozen (live). The liquid cargos include nutritional liquids such as various fruit juices (e.g., orange juice), and industrial organic liquids such as some alkanes (paraffin), alkenes (olefins), alkyne (acetylene), alkanes (aldehydes), etc.

Among the frozen commodities, meat and fish dominate, and are generally stored at equal low temperature

ϑFM ~ −18 °C, although the meat is often carried unfrozen in vacuum packs in the temperature range

ϑMV ~ (−2 to 10) °C depending on the type of meat and the duration of storage [

35].

Micro-climate storage of the unfrozen (living) perishable products, among which prevail bananas, citruses, deciduous fruits and vegetables, is characterized by a relatively high relative humidity (

φlp ~ 0.8 to 0.95), moderately low temperature

ϑlp ~ −2 to 15 °C and a relatively small proportion of fresh air (a small refreshment

g0 1.5 ~ 2.5%). Nutritional liquids are refrigerated and held in separate tanks in an inert gas atmosphere, with the temperature depending on their respective sugar contents, for example, orange juice is held at

ϑOJ ~ −7 °C, [

36].

Typical industrial organic liquids are stored at appropriate saturation temperature

ϑs (

pa) at normal atmospheric pressure

pa, and are as follows: paraffins (C

4H

10 n-butane −0.5 °C, isobutane −11.7 °C, cyclobutane 10 °C), olefins (C

4H

8 butene −6.6 °C, C

4H

6 cyclobutene 2.2 °C), acetylenes (propyne −23.2 °C, butyne 7.7 °C and aldehydes) methanal −19 °C, ethanal 20.2 °C, etc., [

37].

With cooling sea water of ϑsd ~ 32 °C and with a heating sink of ~ 120 °C (low-pressure saturation steam ~ 2 bar), attainable temperature from mixture extracted water as primary refrigerator in the evaporator of lithium bromide ARU amounts to ϑse ~ 5 °C; hence, by the usual arrangement of the cooling system with water as secondary refrigerator in ships’ accommodation air-conditioned systems, the conditioning air can be cooled down to a temperature of ϑac ~ 13 °C, and consequently the application of this ARU to create the desired level of comfort is particularly suitable in air conditioning systems of passenger ships. Generally, there is a possibility that the same ship simultaneously carries different cargo stored in separate compartments with the appropriate prescribed microclimate. Taking into account ships’ accommodation, balancing of the appearing cooling load of such a ship can be achieved either with two apart single-stage AARUs, one for “dead” and another for “live” products (which is expensive), or with a double-stage ARU for the both “dead” and “live” products, and with one lithium bromide LBARU for ships’ accommodation.

In the case of the balancing of cooling load from “dead” product compartments, the overall occurring cooling load is absorbed by the circulation air, which is then cooled in the pertaining air coolers (AC) by the CaCl2 brine, and furthermore, it is refrigerated in evaporator AARUs by the very rich ammonia water mixture. Transportation of “live” product is characterized, in addition to moderate temperature storage, by the removal of the products of their own metabolism followed by fresh air, and with continuous control of relative humidity air in compartments. Regulating the moisture content while balancing the ongoing cooling load and the continuous (or periodic) supply of fresh air, in addition to cooling it, also requires its heating in the air heater.

In the secondary cooling circuit of both cases, the secondary refrigerator CaCl

2 brine circulates by an electric motor driven cooling brine pump (CBP), while the compartment air is recirculated by an electric motor-driven recirculation air fan (RAF), and in transportation of “living” perishable goods the extraction of a part of the air saturated with products of their metabolism is ensured by a special extraction fan (EF). Although many times, depending on market conditions, the reefers simultaneously carry two or more different moderate refrigerated commercial cargoes to separate compartments, in order to define the appropriate cooling systems, it is assumed that during a voyage cycle reefer transport only one type of commercial cargo is transported. Here is an unambiguously defined sailing route. The transport of five different types of cargo is considered: dead-frozen meat (FM) and meat in vacuum packs (MVP), live perishable bananas (B), citruses (C—citrus fruits, e.g., oranges, lemons, grapefruits) and deciduous fruits (DF—kiwi, pears and apples). There is a possibility that, on the one hand, during the regime of navigation that the majority of occurring unsteady cooling and heating loads are balanced by MDETES, while on the other hand, during standstill reefer at final terminal destination, balancing of the corresponding generated cooling and heating loads is carried out by either CRP and FSG, respectively, or by installed absorption chillers that are in this case powered by heat flow produced in FSG. ARU cookers and HFO final heather (HFOFH) together with other ship’s steam consumers (OSSC) determine the overall total unsteady heating load

, which is balanced by the dry-saturated steam of

ps ~ 8 bar produced in a single-pressure cogeneration system characterized with medium-pressure evaporator (MPE) and steam drum (MPD). In the case of the extended form of the cogeneration plant, whose application is based on the using of corrosion-resistant materials, additional main items are included, including a low-pressure steam drum (LPD) and low-pressure evaporator (LPE) that utilizes the remained waste heat from diesel motor exhausted gas after its passage through MPE. Simplified functional diagram

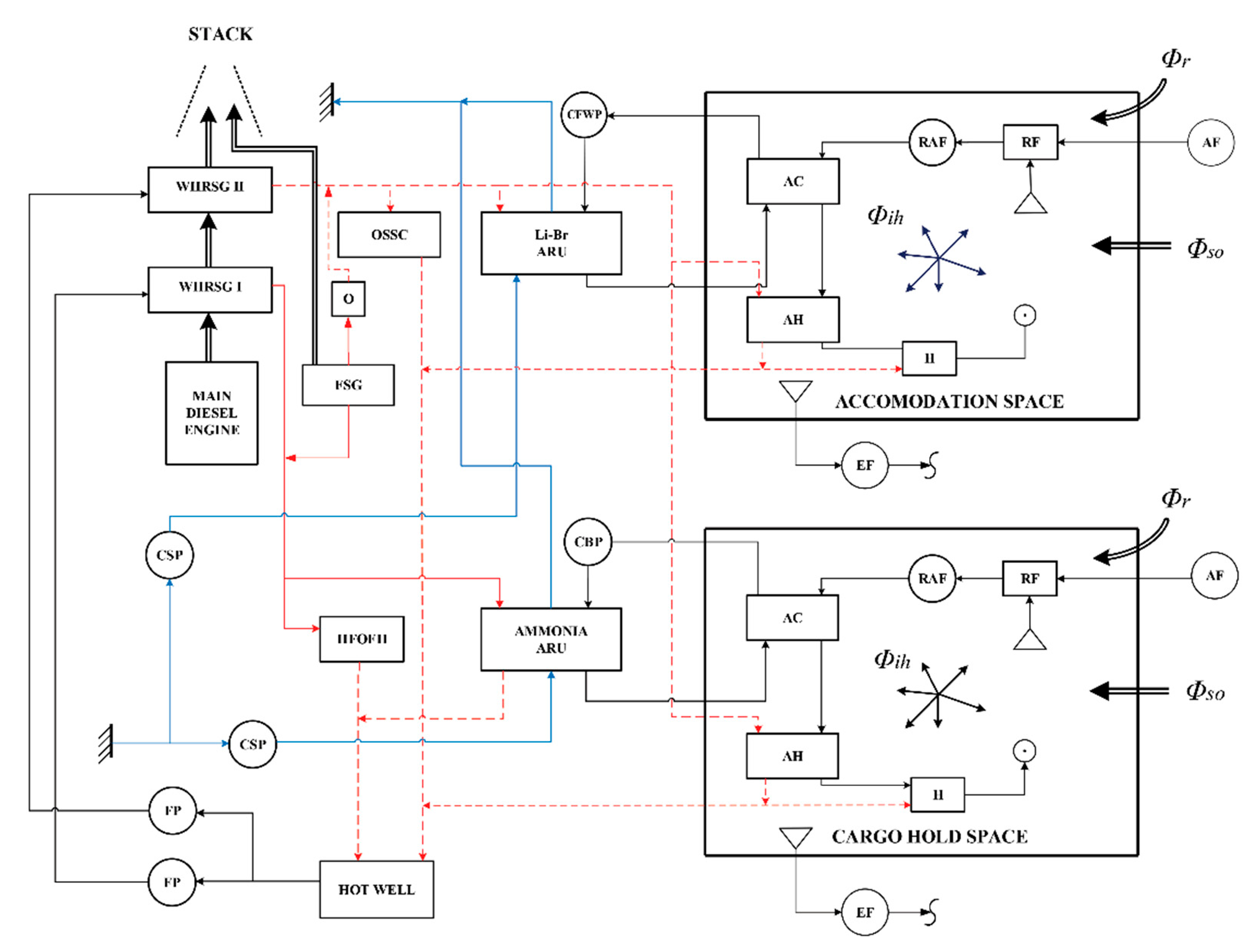

Figure 1 illustrates the plain original MDETES, the application of which could be found on ships for transport of moderate refrigerated cargoes. Based on the submitted schemes, the following can be concluded. The reference design version of the ship’s heating and cooling system is characterized by the required heating effect being produced by the combined steam generator (CSG = FSG + WHRSG), while the cooling effect is produced by a CRP. The introduction of the trigeneration concept offers a trigeneration design version characterized by the fact that during the entire transport cycle the occurring cooling load is balanced by the appropriate ARUs, while by the WHRSG unbalanced amount of the overall unsteady heating load is balanced by the FSG. In order to achieve sufficient redundancy, it is recommended in the case of application of the trigeneration concept to install the CRP of the corresponding cooling effect.

Description of the Trigeneration Scheme

The enclosed

Figure 1 illustrates a simplified scheme of generic MDETES. The functional-interactive connection of the involved subsystems with the flows of the involved media—engine exhaust, water vapor, heavy fuel oil, cooling freshwater, cooling brine, cooling sea, and air of accommodation air conditioning system (AACS) and air of cargo storage air conditioning systems (CACS)—does not illustrates interactive links within the building subsystems of the involved absorption devices (AARU and LBARU).

During navigation, the two-pressure WHRSG is driven by the exhaust gases of the MDE, which simultaneously produces medium-pressure and low-pressure water vapor to balance the corresponding unsteady heat loads—HFOFH and AARU with medium-pressure steam, LBARU, AHa, AHc, and OSSC (Other Ship’s Steam Consumers, such as heaters in HFO S&TS (HFO Storage and Treatment System), as well in HPW (Hot Portable Water)) with low-pressure steam—whereas in cases of insufficient cogeneration effect, the unbalanced part of the occurring heat load (including the heat load of the heavy fuel heater of the fired boiler (FHFSG)) is balanced with medium-pressure steam generated by the fired boiler. In both cases, the medium-pressure and low-pressure condensate are transferred to the hot well (HW) by the appropriate condensate lines. In the air conditioning systems of housing and storage, the extraction of the precisely prescribed part of the metabolic products of saturated air is carried out by extraction fans (EFa and EFc). The amount of the fresh air replacing extraction saturated air and that is mixing with the recirculated saturated is regulated by the regulation flap (RF), immediately in front of recirculation air fans (RAFa and RAFc). The mass flow of this mixture, its temperature, and relative humidity at the outlet of the associated conditioning units, must lie in the prescribed range of comfort parameters to ensure the balance both of humidity and the resulting overall heat load of the air-conditioned space. That is achieved by an appropriate distribution system and by appropriate cooling and/or heating, as well as possible humidification of the same. The unsteady heat loads in the air coolers (ACa and ACc) are balanced by the secondary coolers (fresh water in AACS and brine in CACS), while unsteady heat loads in the associated air heaters (AHa and AHc) are balanced by the low-pressure steam. The secondary coolers are cooled in the evaporators of the respective ARUs. The total heat loads there are increased by the thermal gains of the pertaining conductor systems. The unsteady cooling effect’s generation in ARU evaporators causes the occurrence of unsteady heat loads of contained heat exchangers: cookers that are balanced by water vapor from the cogeneration system, as well absorbers and condensers that are balanced with the cooling sea supplied by the electrically driven cooling brine pump (CBP) of low power rate. In practice, by applying the trigeneration concept, the overall thermal load of the AACS and CACS is balanced by generating the appropriate cogeneration heat output. When transporting “dead” products, there is no need for air conditioning of the storage air, so despite the significantly lower storage temperatures than for “living” products, the thermal load of the storage of “living” products is much higher. This is primarily due to the appearance of increased infiltration heat gains inherent to refreshing. Practically, when maintaining the prescribed micro-climatic conditions of the storage space, a slight change in the intensity of refreshing significantly changes the occurring heat load of the air conditioning system, which may lead to the need for a short-term (but permissible), slight reduction of refreshing in conditions of temporary insufficiency of cogeneration. When modeling MDETES, this scenario was also taken into account, which is confirmed by the results of the simulations of the occurring heat load during navigation for the set refreshing intensities.

The

Figure 1 symbols are; AF—Air Filter, AC—Air Cooler, AH—Air Heater, CBP—Cooling Brine Pump, CSP—Cooling Sea Pump, H—Humidifier, HFOFH—Heavy Fuel Oil Final Heater, OSSC—Other ship’s Steam Consumer, RF—Regulation Flap, RAF—Recirculation Air Fan, FP—Feed Pump, O—Orifice, WHRSG—Waste Heat Recovery Steam Generator, FSG—Fire Steam Generator, EF—Extraction Fan, CFWP—Cooling Fresh Water Pump.

3. Mathematical Modeling Methodology of Energy Interactions of Ship and Environment during Navigation

In order to calculate the performance of the proposed system, models of each respective component are built. Modeling and simulation of the complex physical system are made in Wolfram Mathematica environment.

During the navigation on the predefined navigation route, the ship’s energy system balances the occurring unsteady loads which are fluctuating in a wide range of values due to the action of unsteady and intermittent excitation of the occurring characteristic scalar and vector quantities of the environment, as illustrated in

Figure 2. The contained sizes are: vectors—

and

are sea current and wind velocity, respectively (these vectors are aligned in the tangential plane of the sphere),

is vector of the solar irradiance; scalar—

,

and

are yearly average daily air temperatures (DAT), yearly average temperature differences between max and min DAT, monthly average temperature differences between yearly average DAT, respectively;

—the saturation level of the moist air;

—sea temperature at the depth

d measured from the free surface;

and

—sky coverage with the clouds and the attenuation of the sun’s radiation due to clouds, respectively;

and

—significant wave height and period, respectively.

By available reliably statistically processed data of the occurring environment values over a defined navigation route [

38], it is possible to create appropriate mathematical formulations that express the dependence of these quantities on calendar time

ty and geographical position with given either latitude

φ or longitude

μ. The mathematical model for each defined navigation route is a precise mathematical explicit approximate functional dependence between latitude and longitude—

φ(

μ) or

μ(φ), respectively—either in the form of a polynomial or a trigonometric order with sine terms, as follows:

while in the case of sailing on an orthodrome,

μr(φr) is defined by the following formula:

Based on that, any emerging j-th scalar or vector item of the environment that interacts with the ship’s power system on the navigation route can be represented in the form of the product of trigonometric series of sine functions depending on

tγ and

φr as follows:

Thus, for example, based on the obtained statistical data for the characteristic ambient air temperatures, it is possible to create a mathematical model for the atmospheric air temperature on a certain navigation route, as follows:

For the fluctuation period of the

, it seems appropriate to take half an average synodic month

, where the length of the mean solar day is

, from which it follows for an unsteady circular frequency

. The fluctuation period for

can be obtained by the fact that the daily temperature minimum occurs just after dawn, whose unsteady phase shift is

, and which possesses the apparent circular frequency

. Using this methodology, models of characteristic air temperatures were developed, which are illustrated in the

Figure 3. Similarly,

Figure 4 illustrates wind speed and significant wave height.

Ignoring the geoid shape due to the flatness of the sphere, the navigation route can be defined with sufficient accuracy by a position vector which, with a defined dependence

, taking into account the radius of the sphere

re = 6376.5 km, becomes:

According to, the sailing speed can be defined as follows:

The overall navigational resistance increased by the amount of propulsion reduction for a given ship’s loading condition

, which is charged to the propeller, except for the navigation speed

and the continuous increase in resistance due to hull pollution and fouling, depends on the occurring vector quantities: wind

, sea currents

, and waves

[

39,

40], which according to (3) are dependent on

and

. The propeller-generated thrust force

required to balance this load and the required torque of the propeller

, in addition to its speed

n or wing pitch

p, depend on the average sea inflow speed into the propeller disk

, which depends on the modulus of sailing speed

and the mean coefficient of wake

w, whose functional dependence as well as ship’s thrust deduction coefficient

are defined by the expression:

Taking into account the above mathematical formulations, the quasi-static characteristics of thrust and torque take on generalized functional dependencies:

The generalized functional dependence of the overall quasi-static thrust load (taking into account the total time spent in the service after the docking

) is formulated by the expression:

The actual torque of the MDE which balances the oncoming propulsion load increased by the counter friction torque of the propeller shafting , except for n, depends on the motor load factor which is on the fixed geometry of the propeller (FPP, p = const.), the only control variable which ensures (with constant fluctuation of n and ) safe, reliable and seakeeping acceptable navigation.

Ignoring the emerging capacitances within the DEPS (diesel engine propulsion system), to conduct credible navigation simulations through a realistic environment, it is necessary to set up an appropriate system of dynamic equilibrium of thrust and torque equations as follows:

where:

is the mass of the loaded ship increased by the mass of the surrounding water affected by the movement of the ship (about 10% of the mass of the ship), and

is the polar moment of inertia of all rotating masses of the propulsion system increased by the inertia of the propelled sea mass.

This system of nonlinear differential equations (2nd order

and 1st order

), solvable exclusively numerically based on the prescribed initial conditions

, gives unknown time dependencies

and

during navigation between destinations A and B, sailing duration

. Furthermore, by the numerical processing of

,

is obtained and according to (6) unsteady sailing speed

is calculated; additionally, based on both the

and SMCR (Service Maximum Continuous Rating) of MDE, the time dependency control variable

is also obtained. In principle, the simulation of navigation from B to A is the same, except that the prescribed initial parameters and conditions are different, and thus the functional dependences of unsteady quantities on time

,

,

,

are obtained with the duration of navigation

, which are illustrated in

Figure 5.

With the estimated time intervals of stay in the final destinations

and

, the total duration of the

kth transport cycle is:

, so when simulating navigation in the (

k + 1)’s transport cycle, the time parameter

is obtained:

By using models for air and sea temperature (according to Equation (3)) and ship sailing speeds during the transport cycle (obtained from simulated navigation through realistic surroundings) the unsteady profiles of air and sea temperature are obtained as illustrated in

Figure 6.

3.1. Quasi-Static Effect of Cogeneration System Scheme

Taking into account predictable values of mass flow and temperature of MDE exhaust gases at the SMCR (Service Maximum Continues Rating), and by estimating techno-economically acceptable minimum temperature difference at the WHRSG outlet, the main cogeneration design parameters can be determined, such as exhaust gas outlet temperature and heat exchanger area A. Its required area A is determined for the selected configuration, which is interactively related to the overall heat transfer coefficient k.

During navigation, the fluctuation

and

at the WHRSG inlet, with the determined temperature of the generated steam

and the selected configuration of the overall flow surface

A, leads to volatility

, so based on the energy balance and the applicable mathematical formulation for heat exchange via mean logarithmic temperature difference (MLTD-

), unsteady cogeneration heat effect is obtained:

where:

is the heat capacity of exhaust gases, and

is the exchanger heat transfer capability.

The total unsteady overall heat transfer coefficient

corresponding to

Ai is defined by the expression:

where the appropriate heat transfer coefficients are

and

on both the steam and exhaust side, and

is markedly dependent on the oncoming mean temperature

and on the mean flow rate through the exchanger section

.

Taking into account the functional dependence of the emerging operating parameters of the diesel engine and , as well as the ambient air temperature during navigation, their involvement in (10) easily results in the emerging thermal effects of the cogeneration system and .

When using a two-pressure cogeneration system, the steam production process takes place in such a way that even when

, all available flue gas heat flow is used to produce medium-pressure steam, which results in the flue gas temperature at the inlet to the low-pressure evaporator being exactly equal to the flue gas temperature outlet of the medium-pressure evaporator

:

Thus the available heat output of the low-pressure evaporator is obtained:

where

is the heat transfer capability of the low-pressure evaporator, the flow surface

and the total heat transfer coefficient

. Using mathematical models expressed in formulas (13) and (16), the unsteady MP cogeneration effects

and

(during navigation; from

A to

B and from

B to

A, respectively), as well unsteady LP cogeneration effects

and

(during navigation; from

A to

B and from

B to

A, respectively) for 1st and 2nd transport cycles were calculated and shown in

Figure 7.

3.2. Quasi-Static Heating Loads Scheme

The total unsteady heat load of the ship’s power system during navigation between the final destinations A and B

consists of an MP heat load balanced with MP steam

and an LP heat load balanced with LP steam

, defined by the corresponding terms as follows:

where unsteady heat loads are contained as follows:

represents AARU cookers;

represents HFOFH;

represents LBARU cookers;

and

represent AH in the AACS and CACS, respectively; and

represents OSSC heaters. Unsteady heat loads of AARU and LBARU cookers are defined by the terms:

where

and

are cooling effects of AARU-a and LBARU, respectively, and

and

are their coefficients of performance (COP).

and

are functionally dependent on the equilibrium pressures in the evaporator

, and on the unsteady temperature of the cooling sea water

, which limits the evaporation range for a certain mixture when there is the steady heating source of the cooker (water vapor from the cogeneration system). As

is lower, the possible evaporating range is higher, which increases COP, as illustrated in

Figure 8.

Unsteady cooling effects corresponding to the occurring heat loads of AARU and LBARU evaporators are:

where:

and

are the heat loads of air coolers in climatization systems of cargo spaces and accommodation, respectively;

and

are the mechanical powers of the cooling brain pumps (for cargo space) and cooling fresh water pump (for accommodation), respectively; and

and

are the heating incomes of the conducting systems from pertaining surroundings.

The heat loads of both climatization system (storage space and accommodation) depend on both predefined microclimatic comfort parameters (mainly air temperature and relative humidity), and total sensible and infiltration heating loads. In principle there are two emerging characteristics operating scenarios, either humidification or dehumidification of the wet air mixture as a result of mixing of the recirculation air from climatization space and fresh air from surroundings (

Figure 9).

Consequently, heat loads of air coolers are defined according to the corresponding formulas for cases of humidification and dehumidification as follows:

Humidification and cooling, if

, and

,

Dehumidification and heating, if

,

,

where moisture contents are

and specific enthalpies are

(per kg dry air);

and

are for air of air conditioned space;

,

and

,

are for wet air mixture obtained by mixing of the recirculated air and fresh environmental air, in the corresponding cases when cooling or heating is carried out;

and

are for saturated wet air after excessive moisture extraction (from the condition that is

); and

is temperature of water for humidification.

Specific enthalpies of wet air when

are defined by the following formula:

where:

,

and

are specific heat capacities at

p = const. of the dry air, water steam and water, respectively;

is specific evaporation heat of water steam at

; and

is wet air temperature.

Further specific enthalpies and moisture contents of the wet air mixtures are defined by the corresponding expressions as follows:

and according to (24), (25) and (26) the temperature of the mixture is defined as follows:

where:

and

are mass fractions of the fresh air and recirculated air, respectively; and

,

,

are mass flows of the fresh air, recirculated air and air mixture, respectively.

Finally, there are: —power of recirculating fan electromotor, —heat gains of the air distribution ducting system, and —sensible heating loads of the climatizated space.

In the occurring air conditioning processes of both air conditioning systems (for cargo space and accommodation), it is necessary that the air is heated, apart from in the case of humidification plus cooling (

Figure 9a); hence, heating loads of air heaters are defined as follows:

Humidification and heating, if

, and

),

Dehumidification and heating, if

and

,

3.3. The Sensible Heating Load

This load involves heat flows exchanging between the air conditioned space and surroundings

, and internal heat gains

including the respiration heat flow

, either from live products (cargo hold space) or people (accommodation), as well from contained energized equipment such as lighting, etc. For defining the

, a concept of the quasi-static thermal network is used for both cargo hold space and accommodation, illustrated for the latter in

Figure 10. By implementation of this concept, sensible heat load of a ship’s air conditioned space is defined by the formula:

where contained heat resistances are as follows:

Involved items in formulas (30) and (31) are: , , , and , , the convective heat transfer coefficients on the outer (indices o) and inner (indices I) flat surfaces of ship’s enclosures that are in interacting with; environmental air (indices k), surrounding air non air conditioned ship’s compartments (indices p), and sea (indices sw); , and are areas of the ship’s flat surfaces of the enclosures indexed by k, p and sw, respectively; and and are thicknesses and heat conductivity of the involved multilayer enclosures (, and are pertaining layers’ number enclosures indexed, respectively, by k, p and sw), respectively.

Further, is temperature of the pth non-air conditioned ship’s compartment and is sea temperature on the place corresponding to sea depth at the center of swth flat surface wetting by sea water, and is absorbance of the kth ship’s flat surface exposed to solar irradiation, the intensity of which is displayed as .

3.4. Solar Irradiation

For any

kth ship’s flat surface exposed to solar radiation intensity of the overall acting solar irradiation,

is defined by the following formula:

where:

,

and

are intensities of the solar irradiation directing normally on the sphere tangential surface (

Figure 11), diffuse sky irradiation and overall reflected solar irradiation by the sea surface, respectively. These components of irradiation are defined by the corresponding expressions as follows:

where

is the diffuse irradiation parameter depending on changeable amounts of the moisture and dust particles in the atmosphere [

41],

and

are the intensities, and

is the reflectivity of the sea surface.

By using the solar constant

, the direct extraterrestrial irradiation is defined by approximated expression

[

42], or more precisely by the formula:

where

is the mean Sun chromosphere radius,

is the mean radius of the Earth’s atmosphere,

,

is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant,

is the absolute chromosphere temperature, and module of radii vector of the Earth’s path around of the Sun is:

where

are the big semi-axes and is the

eccentricity of the elliptical path, and finally the revolution angle of the Earth around of Sun is defined, according to [

43], by the formula:

where

and

are contained constants,

is the mean angular velocity of Earth’s revolution around the Sun, and

is the revolution period.

The atmosphere attenuation factor is defined by

[

40], while irradiation attenuation produced by the cloudiness depends on the factor

.

That is simulated by applying formula (3) on the obtainable data from isonephs maps (line connecting the places with equal mean cloudiness), which is illustrated in

Figure 12a and by use results for navigation trough realistic surroundings, the unsteady attenuation factor while transport cycle is obtained as shown in

Figure 12b.

Sun high

is defined by the scalar product of unity vectors, the normal of the tangential surface of the sphere

and acting Sun radiation

(

Figure 11):

where unity vectors are involved as follows:

where

is the Sun’s inclination according to:

Further,

is defined by formula:

where

is the unity normal of

kth arbitrarily placed ship’s flat rectangular surface, defined by vector’s product of the pertaining unity base vectors as follows:

In this formula, contained orts are:

Further, contained angles

and

present azimuth and elevation of a

kth ship’s flat surfaces, respectively, as shown in

Figure 11b.

Other parameters involved in above expressions are:

—min. inclination for north hemisphere,

—time shift for perihelion,

—time shift for winter solstice to which corresponds angle shift

; finally, of the course in modelling through a transport sequence,

ts timing relations

must be taken into account.

Figure 13 illustrates overall solar irradiations for the (a) navigation

A to

B, and (b) navigation

B to

A.

Finally, by applying the above-mentioned for characteristic quasi-static ship’s energy items during the navigation through any transport cycle, the example illustrated by

Figure 14 for unsteady heat load is obtained.

Taking into account that all design parameters of the involved heat exchangers are predetermined on the extreme base values of pertaining heat loads, such as heat exchange areas, overall heat transfer coefficients, mean logarithmic temperature, etc., and assuming that heat capacities of the involved cooling (heating) media (fresh water and brain), as well as heat transfer capabilities of exchangers, are unchangeable during navigation, it can be possible to determine the corresponding quasi-static balanced temperatures on the side cooling media contained in LBARU and AARU.

As an example,

Figure 15 illustrates design and unsteady temperatures of the involved cooling media in the air conditioned system of the accommodation, while expressions (46) and (47) define corresponding heat transfer capability and capacities of conditioned air and cooling fresh water:

where

and

are design temperature differences on the ends of the counter flow exchanger.

Further, for characteristics of unsteady balancing temperatures the corresponding expressions are determined:

The inlet temperature of the cooling fresh water in AC is:

The outlet temperature of the cooling fresh water in AC is:

The temperature of the cooling media in the cooling evaporator is:

The temperature of the heating media (LP water steam) in the air heater is:

By adding equal amounts of the heat gains of the cooling media conducting system

on the inlet and outlet of the cooling evaporator,

are obtained for the inlet and outlet temperatures of the secondary cooling media (fresh water or brine) in the cooling evaporator. By using above mentioned quasi-static balanced temperature of the involved media in AACS are obtained, as illustrated in

Figure 16.

5. Conclusions

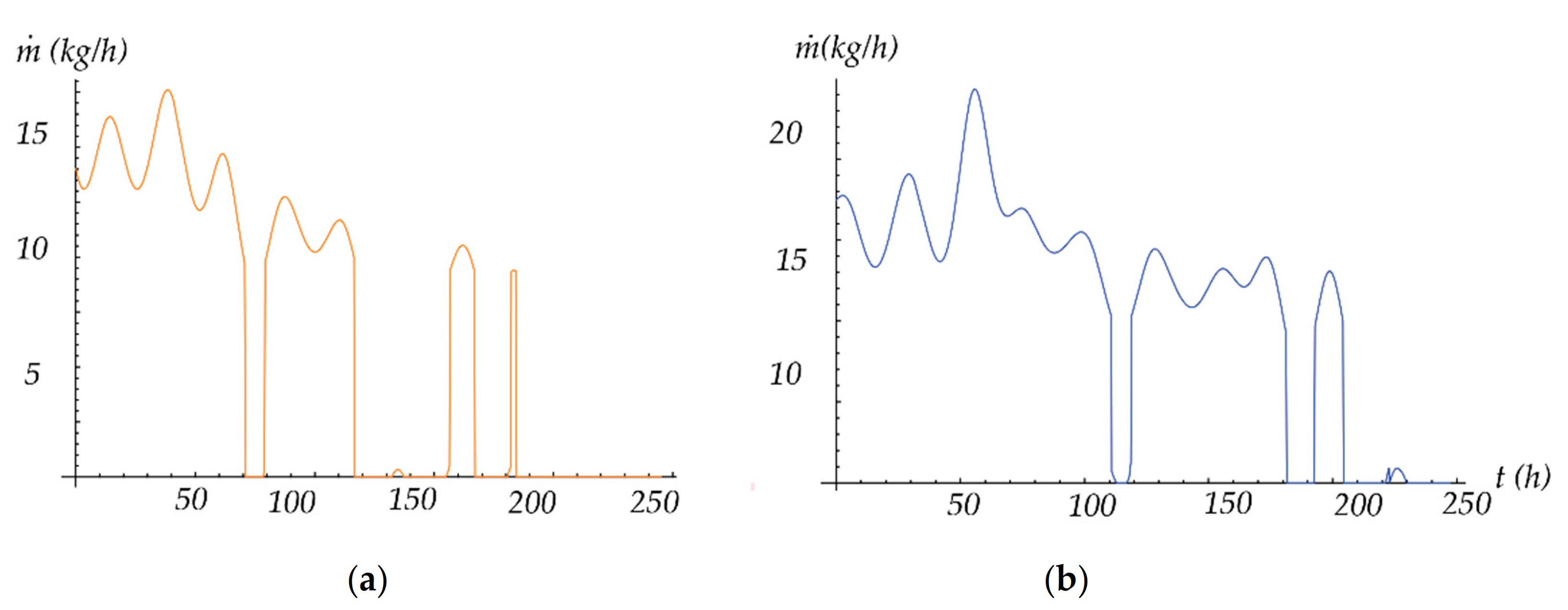

By applying mathematical models of characteristic environment sizes (based on available WMO data), which interact with the ship system and with developed mathematical models of quasi-static characteristics of energy components involved with the diesel engine trigeneration energy system, we created models of unsteady energy balancing during the ship’s characteristic operating intervals. The concept interrelates the trajectory of a vessel and the wave conditions with a detailed described quasi-static model of the energetic, economic and environmental performance of a marine trigeneration unit installed on-board. The developed mathematical models of quasi-static characteristics for single-stage AARUs and LBARUs, enable modelling of unsteady thermal loads of their cookers, absorbers and condensers. Furthermore, the models enable the management of absorption cooling processes in the most energy-efficient way within the emerging unsteady environment.

Within the defined technically possible area of application of absorption cooling, with the application of LBARU for balancing the refrigeration load in the AACS, the application of AARU in CACS is tested for several characteristic moderately refrigerated cargoes: frozen meat, not frozen vacuum packed meat, bananas, citrus and deciduous fruits, where it is shown that on the increasing of the thermal loads, the most influenced variables are: higher intensity of refreshing, lower relative humidity and to a lesser extent the respiratory heat flux of the transported commodity. This implies that the total refrigeration loads when transporting live cargo at the prescribed storage temperature are almost an order of magnitude larger than the corresponding sensible heat loads. Applying these models over a one-year period of service of the ship, which includes 14 repeated transport cycles, it was shown that the trigeneration system is energy sufficient to balance the overall unsteady heat load of ships intended for the transport of moderately refrigerated “dead” and “live” cargo. Quasi-static characteristics of the (CRP) enable the determination of the appropriate fuel consumption that falls on its drive when it balances the unsteady refrigeration load during the navigation.

By integrating the quasi-static fuel consumption curves of the CRP over the intervals of navigation routes for all contained 14 transport cycles, and summing the obtained values, one-year fuel consumption is obtained, i.e., one-year fuel savings. Based on one-year fuel savings, for the estimated economic life of the ship, taking into account the current fuel price as well as additional investment costs of trigeneration and cogeneration plant, significant economic savings were obtained for certain transport combinations, which fully confirm the economically positive effects of the trigeneration concept on ships intended for the transport of moderately refrigerated cargo.

Finally, using the mean reference values for the composition of the LSHFO, and assuming complete combustion, no negligible amounts of reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, especially CO2, were obtained. In conclusion, according to the above, the energy, economic and environmental effects of the application of diesel engine trigeneration energy systems on ships intended for the transport of moderately refrigerated cargo are significantly positive. In addition, the trigeneration energy concept can be applied on modern passenger ships, where the energy amounts required to ensure a high degree of comfort are significant, and often exceed the installation power of propulsion diesel engines.