Improving Mentorship and Supervision during COVID-19 to Reduce Graduate Student Anxiety and Depression Aided by an Online Commercial Platform Narrative Research Group

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Problem of Anxiety and Depression in Graduate Students

2.1. Scope of Graduate Student Experience Related to Anxiety and Depression

2.2. Response of Academic Institutions to Graduate Students’ Anxiety and Depression

2.3. Need for a New Perspective

3. Promoting Resilience through Self-Direction in Graduate Work

4. Two Ways to Approach Truth through Research

4.1. First Approach to Truth

4.2. Second Approach to Truth

5. The Health Narrative Research Group

5.1. Purpose

5.2. Membership

5.3. Method

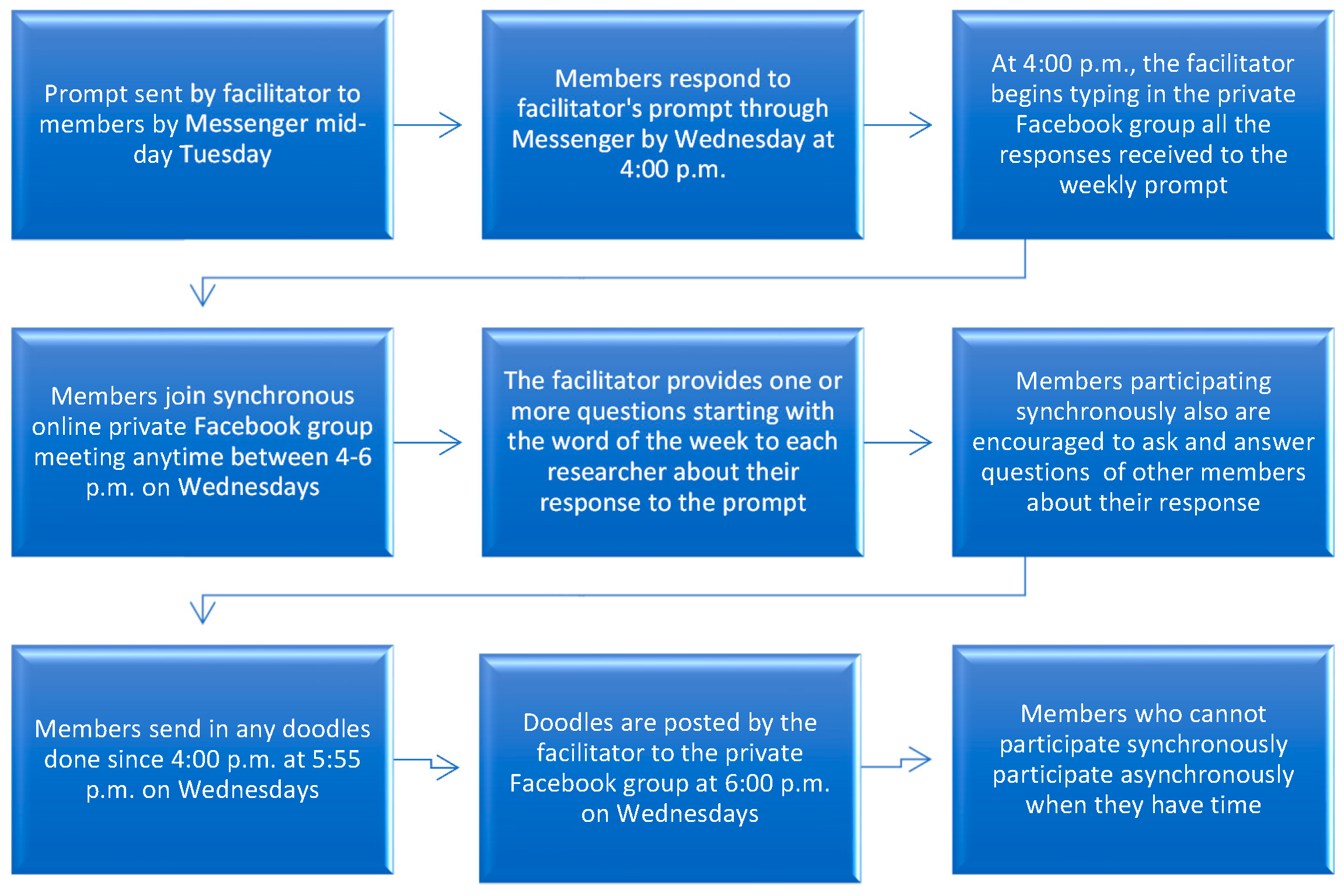

5.4. Online Communication

5.5. Doodling

5.6. Feedback

5.7. Potential Applications of the HeNReG Method

6. Proposed Graduate Narrative Research Groups

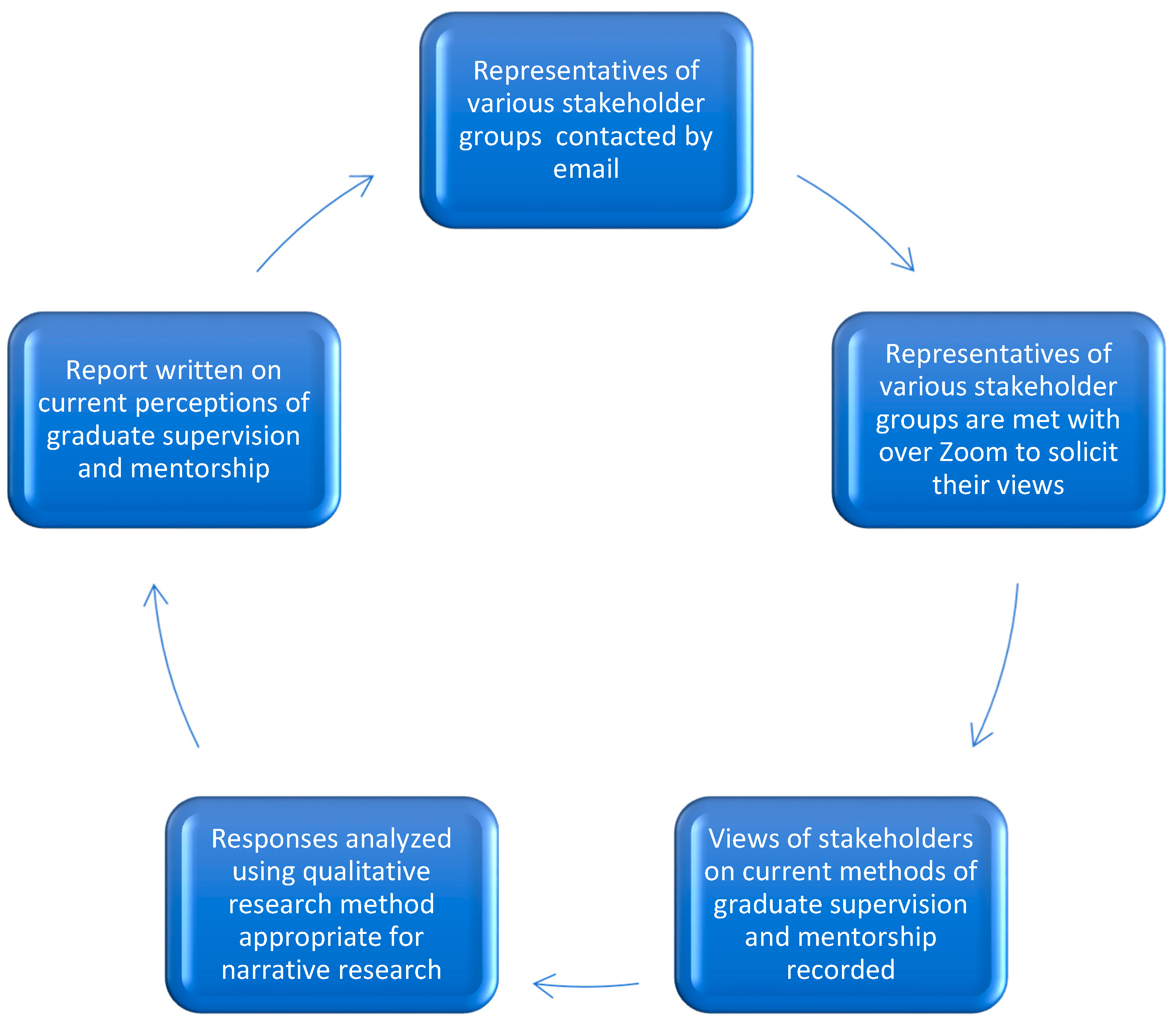

6.1. Phase I

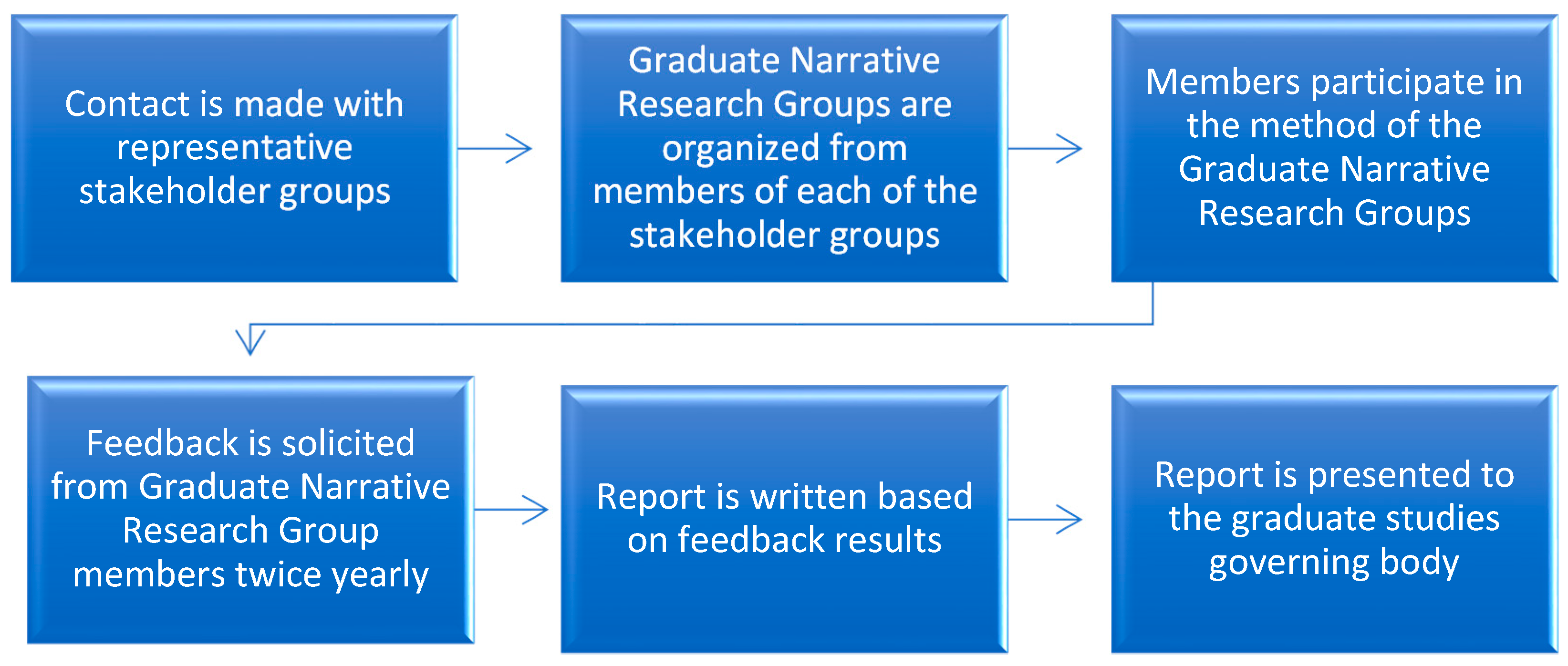

6.2. Phase II

6.3. Phase III

7. Discussion

8. Limitations

8.1. Zoom, Facebook and Messenger as Online Platforms

8.2. Contacting Stakeholders

8.3. COVID-19

9. Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yoho, R. Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Research in Public Health and the Health Professsions Education during a Pan-Demic and Societal Anti-Racism Protests. In Rapid Responses: Researching in the Age of COVID-19, Volume 2: Care and Resilience; Kara, H., Khoo, S.-M., Eds.; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2021; pp. 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Belluigi, D.; Czerniewicz, L.; Khoo, S.; Algers, A.; Buckley, L.A.; Prinsloo, P.; Mgqwashu, E.; Camps, C.; Brink, C.; Marx, R.; et al. “Needs Must”? Critical Reflections on the Implications of the covid19 “Pivot Online” for Equity in Higher Education, Digital Culture and Education. 2020. Available online: https://www.digitalcultureandeducation.com/reflections-on-covid19/needs-must# (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- McGee, E.O. Interrogating Structural Racism in STEM Higher Education. Educ. Res. 2020, 49, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W. Online and Remote Learning in Higher Education Institutes: A Necessity in Light of COVID-19 Pandemic. High. Educ. Stud. 2020, 10, p16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomou, I.; Constantinidou, F. Prevalence and Predictors of Anxiety and Depression Symptoms during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Compliance with Precautionary Measures: Age and Sex Matter. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Feder, A.; Cohen, H.; Kim, J.J.; Calderon, S.; Charney, D.S.; Mathé, A.A. Understanding Resilience. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rackoff, G.N.; Newman, M.G. Reduced Positive Affect on Days with Stress Exposure Predicts Depression, Anxiety Disorders, and Low Trait Positive Affect 7 Years Later. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2020, 129, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W.B. On Being a Mentor: A Guide for Higher Education, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Linden, B.; Stuart, H. Post-Secondary Stress and Mental Well-Being: A Scoping Review of the Academic Literature. Can. J. Community Ment. Health 2020, 39, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotlib, D.; Saragoza, P.; Segal, S.; Goodman, L.; Schwartz, V. Evaluation and Management of Mental Health Disability in Post-secondary Students. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaler, L.S.; Stebleton, M.J. Graduate Student Mental Health: Examining an Overlooked Concern. J. Stud. Aff. 2019–2020, XXIX, 101–110. Available online: https://mountainscholar.org/bitstream/handle/10217/211436/JOUF_JOSA_v29_2019-2020.pdf?sequence=1#page=102 (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Pain, E. Graduate Students Need More Mental Health Support, New Study Highlights. Science 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, T.M.; Bira, L.; Gastelum, J.B.; Weiss, L.T.; Vanderford, N.L. Evidence for a Mental Health Crisis in Graduate Education. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 282–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suart, C.; Suart, T.N.; Graham, K.; Truant, R. When the Labs Closed: Graduate Students’ and Postdoctoral Fellows’ Experiences of Disrupted Research During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Research Square. Available online: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-59050/v1 (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Gilbert, K.E.; Tonge, N.A.; Thompson, R.J. Associations between Depression, Anxious Arousal and Manifestations of Psychological Inflexibility. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2019, 62, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Yu, Y. Anxiety and Depression Aggravate Impulsiveness: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Cognitive Flexibility. Psychol. Health Med. 2020, 25, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besharat, M.-A.; Khadem, H.; Zarei, V.; Momtaz, A. Mediating Role of Perceived Stress in the Relationship between Facing Existential Issues and Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2020, 15, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.; Fawcett, J. The Importance of Anxiety in Both Major Depression and Bipolar Disorder. Depress. Anxiety 2012, 29, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestre, F.T. Ten Simple Rules Towards Healthier Research Labs. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019, 15, e1006914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechuga, V.M. Faculty-Graduate Student Mentoring Relationships: Mentors’ Perceived Roles and Responsibilities. High. Educ. 2011, 62, 757–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coaston, S.C. Cultivating Self-Compassion within the Supervision Relationship. Clin. Superv. 2018, 38, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirikov, I.; Soria, K.M.; Horgos, B.; Jones-White, D. Undergraduate and Graduate Students’ Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. UC Berkeley: Center for Studies in Higher Education, 2020. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/80k5d5hw (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Ruprecht, M.M.; Wang, X.; Johnson, A.K.; Xu, J.; Felt, D.; Ihenacho, S.; Stonehouse, P.; Curry, C.W.; DeBroux, C.; Costa, D.; et al. Evidence of Social and Structural COVID-19 Disparities by Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Race/Ethnicity in an Urban Environment. J. Hered. 2021, 98, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazelrigg, K.; Woodworth, M. New Initiative to Support Graduate Student Mental Health and Wellness. Council of Graduate Schools, 20 August 2019. Available online: https://cgsnet.org/new-initiative-support-graduate-student-mental-health-and-wellness (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Quick Facts (2020) Student Enrolment. University of Toronto Fall 2019–2020. Available online: https://www.utoronto.ca/about-u-of-t/quick-facts (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Provostial Advisory Committee on Student Mental Health. Report of the Provostial Advisory Committee on Student Mental Health: The University of Toronto Student Mental Health Strategy and Framework. University of Toronto, October 2014; pp. 1–61. Available online: https://www.provost.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/155/2018/03/Report-on-Student-Mental-Health.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- U of T Announces Action plan on Student Mental Health. U of T News, 1 April 2019. Available online: https://www.utm.utoronto.ca/main-news/u-t-announces-action-plan-student-mental-health (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- School of Graduate Studies Mental Health Working Group. Recommendations. School of Graduate Studies, University of Toronto, June 2020; pp. 1–5. Available online: https://www.sgs.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/253/2020/10/Mental-Health-Working-Group-Recommendations-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Levine, R. U of T Expert on the Rise of Students Seeking Help for Mental Health. U of T News, 3 April 2019. Available online: https://www.utoronto.ca/news/u-t-expert-rise-students-seeking-help-mental-health (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Levecque, K.; Anseel, F.; De Beuckelaer, A.; Van der Heyden, J.; Gisle, L. Work Organization and Mental Health Problems in PhD students. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 868–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lane, R. Graduate Students: Mind Your Mental Health This Fall Amid Pandemic Stress. Chicago Sun* Times, 28 August 2020. Available online: https://chicago.suntimes.com/well/2020/8/28/21404295/graduate-students-mental-health-covid-19-pandemic-college-resources (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Eleftheriades, R.; Fiala, C.; Pasic, M.D. The Challenges and Mental Health Issues of Academic Trainees. F1000Research 2020, 9, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chirikov, I.; Soria, K.M.; Horgos, B.; Jones-White, D. Undergraduate and Graduate Students’ Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic 2020. SERU Consortium, University of California—Berkeley and University of Minnesota. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/80k5d5hw (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Greer, L.L.; De Jong, B.A.; Schouten, M.E.; Dannals, J.E. Why and When Hierarchy Impacts Team Effectiveness: A Meta-Analytic Integration. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 591–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyranoski, D.; Gilbert, N.; Ledford, H.; Nayar, A.; Yahia, M. Education: The PhD factory. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 472, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelló, M.; Pardo, M.; Sala-Bubaré, A.; Suñe-Soler, N. Why Do Students Consider Dropping Out of Doctoral Degrees? Institutional and Personal Factors. High. Educ. 2017, 74, 1053–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueiras, G.; Iborra, A.; Gloria, N.; Alejandro, I. Understanding and Promoting Self-Direction in Freshman and Master’s Students: A Qualitative Approach. Behav. Dev. Bull. 2017, 22, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, Z.; Roiko, A.; Sebar, B.; Rogers, G.D. Fostering Peer learning and Self-Reflection: A Two-Pronged Strategy to Augment the Effectiveness of Work Integrated Learning Placements. In Educating the Deliberate Professional; Metzler, J.B., Ed.; Springer: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 209–228. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Li, L. ‘Tell Me What to Do’ vs. ‘Guide Me through It’: Feedback Experiences of International Doctoral Students. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2011, 12, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, S.K. “What’s Too Much and What’s Too Little?”: The Process of Becoming an Independent Researcher in Doctoral Education. J. High. Educ. 2008, 79, 326–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyne, J.; Grodsky, E. Inequality and Opportunity in a Perfect Storm of Graduate Student Debt. Sociol. Educ. 2019, 93, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S. Selecting a Doctoral Dissertation Supervisor: Analytical Hierarchy Approach to the Multiple Criteria Problem. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 2007, 2, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maseko, R. Decolonising the Supervision Process in a Westernised University. In The Dynamics of Changing Higher Education in the Global South; Mpofu, B., Ndllovu-Gatsheni, S., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2020; p. 124. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D.T.; Yip, J.; Doiron, K. Protean Careers at Work: Self-Direction and Values Orientation in Psychological Success. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 129–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. Actual Minds, Possible Worlds; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, S. Comment on Hekman’s “Truth and Method: Feminist Standpoint Theory Revisited”: Whose Standpoint Needs the Regimes of Truth and Reality? Signs 1997, 22, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokushkin, M. Standpoint Theory Is Dead, Long Live Standpoint Theory! Why Standpoint Thinking Should Be Embraced by Scholars Who Do Not Identify as Feminists? J. Arts Hum. 2014, 3, 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Thorne, S.; Malterud, K. Time to Challenge the Spurious Hierarchy of Systematic over Narrative Reviews? Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 48, e12931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilot, A.; Bulte, A.M.W. Why Do You “Need to Know”? Context-based Education. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2006, 28, 953–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gewin, V. Mental Health: Under a Cloud. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 490, 299–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pierro, M. Mental Health and the Graduate Student Experience. J. Qual. Particip. 2017, 40, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, T. Doing Narrative Research? Thinking Through the Narrative Process. In Feminist Narrative Research; Woodiwiss, J., Smith, K., Lockwood, K., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pears, D. Wittgenstein’s Concept of Showing. Grazer Philos. Stud. 1992, 42, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Majka, W. Truth and the Phenomenological Landscape of Perception. Respectus Philol. 2012, 22, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissensteiner, E.; Winter, S. Landmarks in the Communication of Route Directions. In Computer Vision; Metzler, J.B., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; Volume 3234, pp. 313–326. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, G. Provisions of Trustworthiness in Critical Narrative Research: Bridging Intersubjectivity and Fidelity. Qual. Rep. 2004, 9, 359–374. [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein, L. Philosophical Investigations, 2nd ed.; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- The Health Narratives Research Group (HeNReG). History of Medicine Program, University of Toronto. Available online: http://history.med.utoronto.ca/content/links (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Team Narrative, Health, Arts and Humanities Program. University of Toronto. Available online: http://health-humanities.com/2018/11/07/team-narrative/ (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Arbor Award 2015 recipient: Carol Nash. Available online: http://history.med.utoronto.ca/content/new-book-tells-remarkable-story-medicine-u-t (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- King, P. In Their Own Words: Meet This Year’s OISE Leaders & Legends Awards Winners. 27 May 2020. Available online: https://www.oise.utoronto.ca/oise/News/2020/Meet_this_year_s_OISE_Leaders_and_Legends_Awards_winners.html (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- Narrative Medicine, School of Professional Studies. Columbia University. Available online: https://sps.columbia.edu/academics/masters/narrative-medicine (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Health and Humanities: Narrative Medicine, Equity and Diversity, and Community Practice. Office of the Vice President for Research, The University of Texas at Austin. Available online: https://research.utexas.edu/vpr-initiatives/health-and-humanities/ (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- The Program for Narrative Medicine and Health Humanities. College of Medicine, Phoenix, The University of Arizona. Available online: https://phoenixmed.arizona.edu/bioethics/narrative-medicine (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- SELMA—Seminar on Medical Humanities, News. Norges Arktiske Universitet. Available online: https://uit.no/forskning/forskningsgrupper/sub?p_document_id=404492&sub_id=404764 (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Medicina Narrativa, Projecto em Humanidades Médicas. The Portuguese Network of Medical Humanities (PNMH). Available online: http://narrativaemedicina.letras.ulisboa.pt/en/research-team/ (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Sandelowski, M. Telling Stories: Narrative Approaches in Qualitative Research. Image J. Nurs. Sch. 1991, 23, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charon, R. Narrative Medicine: Honoring the stories of Illness; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Moen, T. Reflections on the Narrative Research Approach. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josselson, R.; Salkind, N. Narrative Research. Encycl. Res. Des. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Reconsidering Privilege: How to Structure Writing Prompts to Develop Narrative. Surviv. Thrive J. Med Humanit. Narrat. Med. 2020, 5. Available online: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/survive_thrive/vol5/iss2/3 (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Nash, C. Challenges Identifying and Stimulating Self-Directed Learning in Publicly Funded Programs, The Digital Era of Education: Novel Teaching Strategies and Learning Approaches Designed for Modern Students; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 259–300. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, C. Overcoming the Reluctance of Medical Professionals to Embrace Self-Directed Learning in Response to COVID-19. Sciforum 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Report on Digital Literacy in Academic Meetings during the 2020 COVID-19 Lockdown. Challenges 2020, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E. How to Practise Philosophy as Therapy: Philosophical Therapy and Therapeutic Philosophy. Metaphilosophy 2011, 42, 49–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, J. A Russellian Plea for ‘Useless’ Knowledge: Role of Freedom in Education. Stud. Philos. Educ. 2021, 40, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, S.O. Risk: Objective or Subjective, Facts or Values. J. Risk Res. 2010, 13, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Doodling as a Measure of Burnout in Healthcare Researchers. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 2020, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendieta, J.A. Narrative research: An alternative approach to study language teaching and learning. Folios 2013, 37, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoli, C.; Pawlowski, S.D. The Delphi Method as a Research Tool: An Example, Design Considerations and Applications. Inf. Manag. 2004, 42, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Misra, F.; Mazelfi, I. Long-Distance Online Learning during Pandemic: The Role of Communication, Working in Group, and Self-Directed Learning in Developing Student’s Confidence. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Educational Development and Quality Assurance (ICED-QA 2020). Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research. 2021. Available online: https://www.atlantis-press.com/proceedings/iced-qa-20/125952102 (accessed on 3 February 2021).

- Lewis, P.J.; Adeney, R. Narrative research. In Qualitative Methodology: A Practical Guide; Mills, J., Birks, M., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2014; pp. 161–179. [Google Scholar]

- Vorobyova, M.; Kochukhova, E. On the Way to Non-Hierarchical Communication: Methods of Reading and Writing in Teaching Philosophy to University Students. KnE Soc. Sci. 2020, 4, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roberts, D.H.; Newman, L.R.; Schwartzstein, R.M. Twelve Tips for Facilitating Millennials’ Learning. Med Teach. 2012, 34, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoom Video Communications, Inc. Zoom Meeting Plans for Your Business. July 2020. Available online: https://zoom.us/pricing (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Why Zoom Is Terrible. Available online: https://hsc.unm.edu/school-of-medicine/education/assets/doc/wellness/murphy-why-zoom-is-terrible-nyt.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Why Does Zoom Exhaust You? Science Has an Answer. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/why-does-zoom-exhaust-you-science-has-an-answer-11590600269 (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Wiederhold, B.K. Connecting Through Technology during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic: Avoiding “Zoom Fatigue”. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 437–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.; Hargittai, E. Facebook Privacy Settings: Who Cares? First Monday 2010, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Woo, H.L.; Quek, C.L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, M. Using the Facebook Group as a Learning Management System: An Exploratory Study. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2012, 43, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meishar-Tal, H.; Kurtz, G.; Pieterse, E. Facebook Groups as LMS: A Case Study. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2012, 13, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Epperly, D. Evidence For COVID-19 Vaccine Deferred Dose 2 Boost Timing. SSRN Electron. J. 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, M.D.; Wonodi, C. Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 Vaccine Efficacy. Lancet 2021, 397, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, E.H.; Malani, P.N.; Creech, C.B. The Johnson & Johnson Vaccine for COVID-19. JAMA 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C. New COVID Vaccines Need Absurd Amounts of Material and Labor. Scientific American, 4 January 2021. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/new-covid-vaccines-need-absurd-amounts-of-material-and-labor1/ (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Kharroubi, S.; Saleh, F. Are Lockdown Measures Effective Against COVID-19? Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 549692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P. Closure of Universities Due to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Impact on Education and Mental Health of Students and Academic Staff. Cureus 2020, 12, e7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Killgore, W.D.; Taylor, E.C.; Cloonan, S.A.; Dailey, N.S. Psychological Resilience during the COVID-19 Lockdown. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.-A.; Yu, J.J.; Lee, C.-U.; Chae, J.-H. Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies Contributing to Resilience in Patients with Depression and/or Anxiety Disorders. Compr. Psychiatry 2013, 54, 1190–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paetow, G.; Zaver, F.; Gottlieb, M.; Chan, T.M.; Lin, M.A.; Gisondi, M. Online Mastermind Groups: A Non-hierarchical Mentorship Model for Professional Development. Cureus 2018, 10, 3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, M.Y.; Edmondson, A.C. Self-Managing Organizations: Exploring the Limits of Less-Hierarchical Organizing. Res. Organ. Behav. 2017, 37, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depauw, K.P. Evolving Landscape of Global Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities from a Graduate Education Perspective. In Major Challenges Facing Higher Education in the Arab World: Quality Assurance and Relevance; Metzler, J.B., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- What Is SGS? School of Graduate Studies, University of Toronto. Available online: https://www.sgs.utoronto.ca/about/what-is-sgs/ (accessed on 12 March 2021).

| Academic Group | Discipline | Marginalized Group |

|---|---|---|

| Alumni | Diaspora and Transnational Studies | - |

| Graduate Students | Paediatrics | Arab |

| Administrators | Education | - |

| Alumni | Statistical Science | East Asian |

| Alumni | Economics | - |

| Alumni | Bioinformatics and Computer Science | East Asian |

| Graduate Students | Narrative Research | African |

| Faculty | Social Work | - |

| Graduate Students | Information Science | East Asian |

| Faculty | English | African |

| Alumni | Neuroscience, Psychology, Bioethics | Southeast Asian |

| Faculty | Medicine | East Asian |

| Graduate Students | Social Work | - |

| Graduate Students | Education | - |

| Undergraduates | Health Studies and Immunology | - |

| Alumni | English | South Asian |

| Undergraduates | Medicine | Arab |

| Graduate Students | Drama | Homosexual |

| Alumni | East Asian Studies | East Asian |

| Faculty | Medicine | Latin American |

| Rank of Question Objectivity | Order of Questions Posed by Weeks | Number of Weeks Posed |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | When | 4 |

| 2. | Where | 4 |

| 3. | Who | 4 |

| 4. | What | 4 |

| 5. | How | 6 |

| 6. | Why | 6 |

| Phase | Purpose | Online Platform | Feedback Tool |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Gather views | Zoom | Report |

| II | Engage in method | Private Facebook Group + Messenger | Feedback forms |

| III | Design policy | Decision of graduate governing body | Policy |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nash, C. Improving Mentorship and Supervision during COVID-19 to Reduce Graduate Student Anxiety and Depression Aided by an Online Commercial Platform Narrative Research Group. Challenges 2021, 12, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe12010011

Nash C. Improving Mentorship and Supervision during COVID-19 to Reduce Graduate Student Anxiety and Depression Aided by an Online Commercial Platform Narrative Research Group. Challenges. 2021; 12(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe12010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleNash, Carol. 2021. "Improving Mentorship and Supervision during COVID-19 to Reduce Graduate Student Anxiety and Depression Aided by an Online Commercial Platform Narrative Research Group" Challenges 12, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe12010011