A Scoping Review Examining Governance, Co-Creation, and Social and Ecological Justice in Living Labs Literature

Abstract

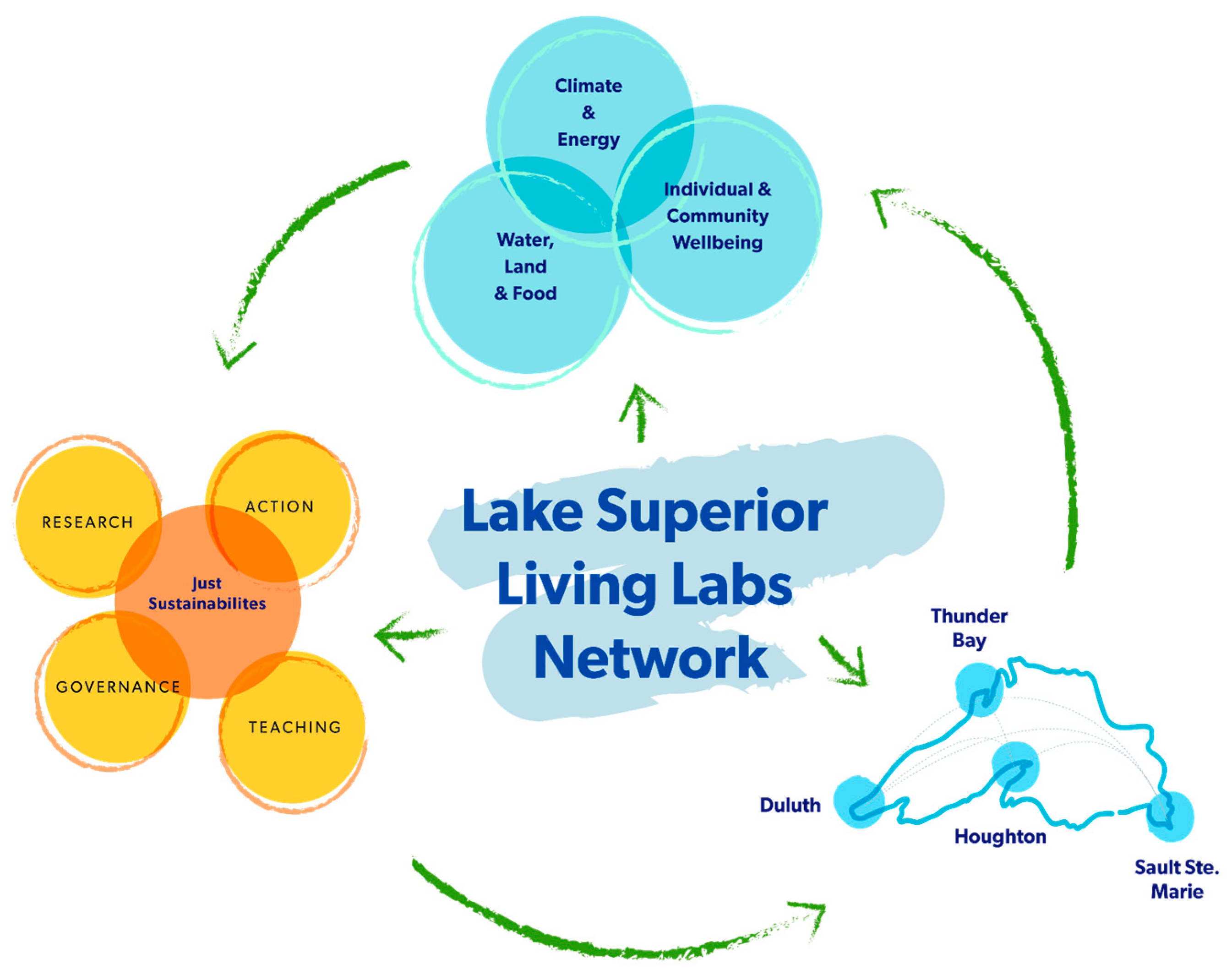

:1. Introduction

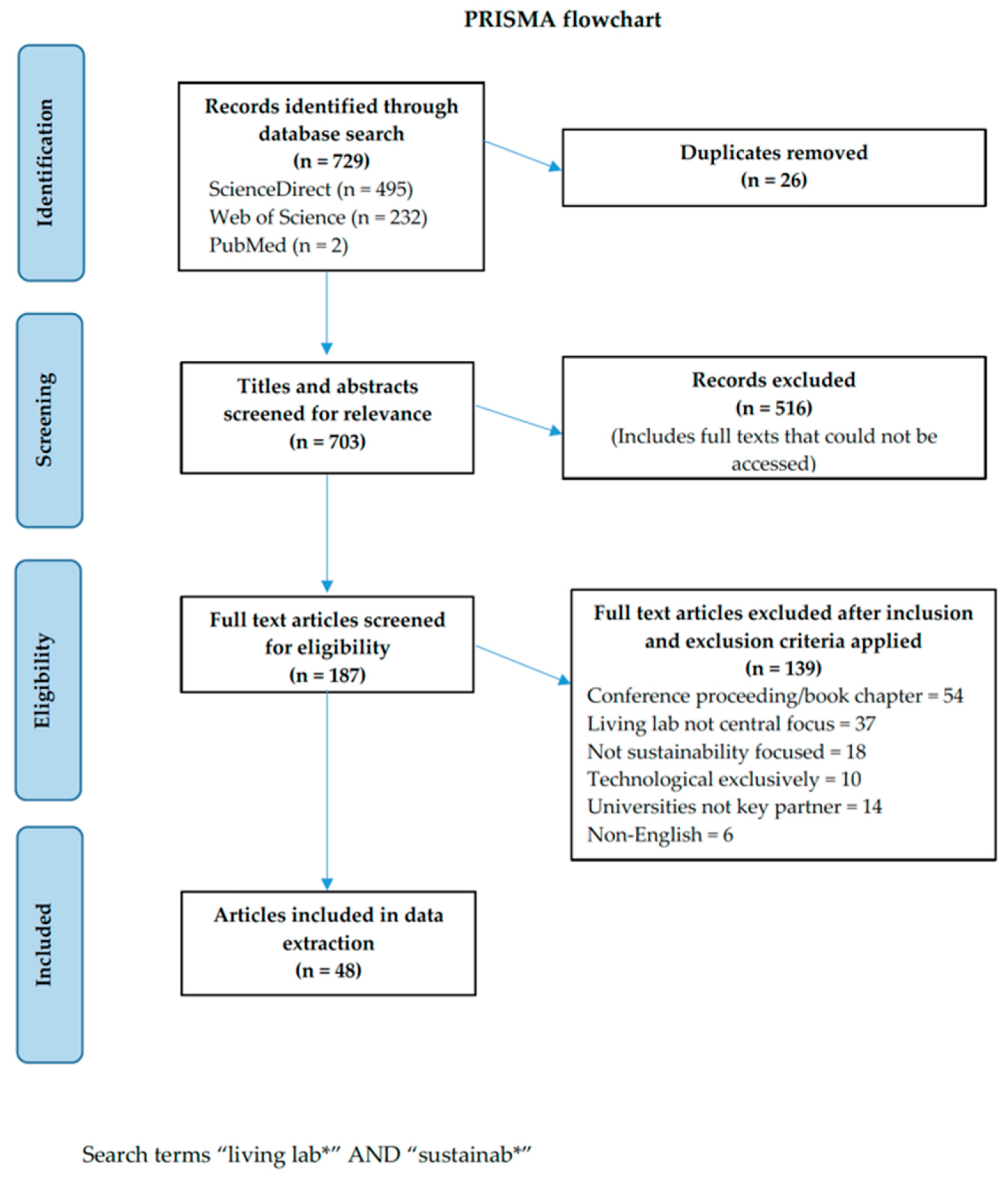

2. Methods

2.1. Identifying the Research Questions

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

2.3. Selecting Studies for Inclusion in the Review

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Collating, Synthesizing, Summarizing, and Reporting Results

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Recent LLs Publications

3.2. Conceptualization, Description, and Application of LLs

“[LLs are] a form of experimental governance, whereby urban collaborators develop and test new technologies, products, services and ways of living to produce innovative solutions to the challenges of climate change, resilience, and urban sustainability.”[20]

“...spaces to facilitate experimentation about sustainability solutions… [urban LLs] represent sites that allow different urban actors to design, test and learn from socio-technical innovations in real time.”[9]

“Urban Living Labs are “transition arenas” which provide “protected spaces” for experimentation and learning in the context of governing urban sustainability transitions.”[21]

“A ‘living lab’ is defined as a situation or circumstance where real-world sustainability challenges are formally addressed in collaborator partnerships…”[22]

“…Living Lab is a tool or a framework for creating services, public goods, market products or ideas.”[23]

“The living laboratory provides a focal point around which stakeholders can work together, generating communities of interest that may well outlive and transcend the living laboratory itself”[24]

“[LLs] are intended to promote the collaboration between a variety of actors and, with their experimental sites, are also considered to have value for long-term sustainability transitions”[1]

“...to bring stakeholders together in a process of co-learning”[25]

3.3. Governance of LLs

3.4. Co-Creation within LLs

“Co-creation as the intended learning process in living labs, ideally, encompasses joint problem-definition and problem-solving using improvisation and experimentation—this in designing, implementation and testing of solutions in an iterative way, while interacting and co-constructing personalized experience”[28]

“...co-creation brings together different policy and practice stakeholders with the aim to develop an outcome that will be valued by all the parties involved in the process”[29]

“A widely accepted generic and literal definition of co-creation is ‘making something together...co-creation is not only a methodology to achieve (product, service, or process) innovation, but a way to create values that are shared between participants.”[1]

3.5. Social and Environmental Justice in LLs Research and Practice

3.6. Limitations

4. Discussion

4.1. Interrogating Governance

4.2. Unpacking Co-Creation

4.3. Working towards Social and Environmental Justice

5. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Puerari, E.; de Koning, J.; von Wirth, T.; Karré, P.; Mulder, I.; Loorbach, D. Co-Creation Dynamics in Urban Living Labs. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bronson, K.; Devkota, R.; Nguyen, V. Moving toward Generalizability? A Scoping Review on Measuring the Impact of Living Labs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, R.; Franco Contreras, J.; Meijer, A. The Living Lab as a Methodology for Public Administration Research: A Systematic Literature Review of Its Applications in the Social Sciences. Int. J. Public Adm. 2020, 43, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Følstad, A. Living Labs for Innovation and Development of Information and Communication Technology: A Literature Review. Electron. J. Organ. Virtualness 2008, 10, 99–131. [Google Scholar]

- Greve, K.; Leminen, S.; De Vita, R.; Westerlund, M. Unveiling the Diversity of Scholarly Debate on Living Labs: A Bibliometric Approach. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 24, 2040003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Leminen, S.; Westerlund, M. A Systematic Review of Living Lab Literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 976–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurman, D.; Baccarne, B.; Coorevits, L.; Georges, A.; Logghe, S. Knowledge Exchange for Innovation Development in Open Innovation Systems. Tijdschr. Voor Commun. 2014, 42, 378. [Google Scholar]

- Westerlund, M.; Leminen, S.; Rajahonka, M. A Topic Modelling Analysis of Living Labs Research. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2018, 8, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- von Wirth, T.; Fuenfschilling, L.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Coenen, L. Impacts of Urban Living Labs on Sustainability Transitions: Mechanisms and Strategies for Systemic Change through Experimentation. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 229–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurman, D. Bridging the Gap between Open and User Innovation? Exploring the Value of Living Labs as a Means to Structure User Contribution and Manage Distributed Innovation. Ph.D. Thesis, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Agyeman, J. Introducing Just Sustainabilities: Policy, Planning, and Practice; Zed Books Ltd.: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-178-032-410-4. [Google Scholar]

- Sze, J. Sustainability: Approaches to Environmental Justice and Social Power; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-147-989-456-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lake Superior Living Labs Network Lake Superior Living Labs Network. Available online: https://livinglabs.lakeheadu.ca/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pham, M.T.; Rajić, A.; Greig, J.D.; Sargeant, J.M.; Papadopoulos, A.; McEwen, S.A. A Scoping Review of Scoping Reviews: Advancing the Approach and Enhancing the Consistency. Res. Synth. Methods 2014, 5, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.E.; Levison, J.K.; McBean, E.A.; Brown, E.; Harper, S.L. Source Water Protection Programs and Indigenous Communities in Canada and the United States: A Scoping Review. J. Hydrol. 2018, 562, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steen, K.; Van Bueren, E. The Defining Characteristics of Urban Living Labs. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2017, 7, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voytenko, Y.; McCormick, K.; Evans, J.; Schliwa, G. Urban Living Labs for Sustainability and Low Carbon Cities in Europe: Towards a Research Agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 123, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharp, D.; Salter, R. Direct Impacts of an Urban Living Lab from the Participants’ Perspective: Livewell Yarra. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Purcell, W.M.; Henriksen, H.; Spengler, J.D. Universities as the Engine of Transformational Sustainability toward Delivering the Sustainable Development Goals: “Living Labs” for Sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 1343–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zingraff-Hamed, A.; Martin, J.; Lupp, G.; Linnerooth-Bayer, J.; Pauleit, S. Designing a Resilient Waterscape Using a Living Lab and Catalyzing Polycentric Governance. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2019, 7, 12–31. [Google Scholar]

- Omrcen, E.; Lundgren, U.; Dalbro, M. Universities as Role Models for Sustainability: A Case Study on Implementation of University of Gothenburg Climate Strategy, Results and Experiences from 2011 to 2015. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Jagt, A.P.N.; Smith, M.; Ambrose-Oji, B.; Konijnendijk, C.C.; Giannico, V.; Haase, D.; Lafortezza, R.; Nastran, M.; Pintar, M.; Železnikar, Š.; et al. Co-Creating Urban Green Infrastructure Connecting People and Nature: A Guiding Framework and Approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 233, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, H.; Hann, V.; Watson, P. Rural Laboratories and Experiment at the Fringes: A Case Study of a Smart Grid on Bruny Island, Australia. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 36, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Institute on Governance. Available online: https://iog.ca/research/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Van Geenhuizen, M. Applying an RRI Filter in Key Learning on Urban Living Labs’ Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zavratnik, V.; Superina, A.; Stojmenova Duh, E. Living Labs for Rural Areas: Contextualization of Living Lab Frameworks, Concepts and Practices. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Menny, M.; Palgan, Y.V.; McCormick, K. Urban Living Labs and the Role of Users in Co-Creation. GAIA-Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2018, 27, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellina, F.; Castri, R.; Simão, J.V.; Granato, P. Co-Creating App-Based Policy Measures for Mobility Behavior Change: A Trigger for Novel Governance Practices at the Urban Level. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 53, 101911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Coenen, L.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Hartmann, C.; Kronsell, A.; Mai, L.; Marvin, S.; McCormick, K.; van Steenbergen, F.; Voytenko Palgan, Y. Urban Living Labs: Governing Urban Sustainability Transitions. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 22, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kooiman, J. Governing as Governance; Sage: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Merenlender, A.; Buhler, B. Climate Stewardship: Taking Collective Action to Protect California; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-052-037-894-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kalinauskaite, I.; Brankaert, R.; Lu, Y.; Bekker, T.; Brombacher, A.; Vos, S. Facing Societal Challenges in Living Labs: Towards a Conceptual Framework to Facilitate Transdisciplinary Collaborations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, H.; Zwakhalen, S.M.G.; Schols, J.M.G.A.; Kempen, G.I.J.M.; Hamers, J.P.H. The Living Lab in Ageing and Long-Term Care: A Sustainable Model for Translational Research Improving Quality of Life, Quality of Care and Quality of Work. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Chelsea Green Publishing: Chelsea, VT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Halseth, G.; Markey, S.P.; Manson, D.; Ryser, L. Doing Community-Based Research: Perspectives from the Field; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada; Kingston, ON, Canada; London, UK; Chicago, IL, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-077-354-727-8. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, B.A.; Schulz, A.J.; Parker, E.A.; Becker, A.B. Review of Community-Based Research: Assessing Partnership Approaches to Improve Public Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1998, 19, 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Israel, B.A.; Eng, E.; Schulz, A.J.; Parker, E.A. Methods for Community-Based Participatory Research for Health; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-111-802-186-6. [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier, J.M.; Buckles, D.J. Participatory Action Research: Theory and Methods for Engaged Inquiry, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-041-554-032-2. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, A. Participatory Action Research; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-141-295-366-5. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, N.; Coolsaet, B.; Martin, A. Justice and Equity: Emerging Research and Policy Approaches to Address Ecosystem Service Trade-Offs. In Ecosystem Services and Poverty Alleviation; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 22–38. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosberg, D.; Collins, L.B. From Environmental to Climate Justice: Climate Change and the Discourse of Environmental Justice. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2014, 5, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The Drivers of Greenwashing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agyeman, J. Toward a ‘Just’ Sustainability? Continuum 2008, 22, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, J.; Bullard, R.D.; Evans, B. Introduction: Joined-up Thinking: Bringing Together Sustainability, Environmental Justice and Equity. In Just Sustainabilities; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-184-977-177-1. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, N. Scales of Justice: Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-023-114-680-7. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, N. Abnormal Justice. Google Scholar. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Abnormal%20justice&publication_year=2008&author=Nancy%20Fraser (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- Blue, G.; Bronson, K.; Lajoie-O’Malley, A. Beyond Participation and Distribution: A Scoping Review to Advance a Comprehensive Justice Framework for Impact Assessment; University of Calgary: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosberg, D. Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-019-956-248-0. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosberg, D. Political Challenges of the Climate-Changed Society. PS Political Sci. Politics 2013, 46, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Published between 1 January 2015 and serach date | Published prior to 1 January 2015 |

| Article is published in an academic journal | Conference abstracts or proceedings, books, book chapters, theses |

| Article is published in English | Language other than English |

| Living lab(s) are an explicit and central focus of the paper | Living lab(s) are NOT an explicit and central focus of the paper |

| Paper explicitly addresses sustainability challenge(s) | Paper does NOT explicitly address sustainability challenge(s) |

| Paper is not focused solely on creating a technological innovation as an end-point/objective | Paper is focused solely on creating a technological innovation as an end-point/objective |

| University(ies) a key collaborator | University(ies) NOT a key collaborator |

| Characteristic of Living Labs 1 | Number of Articles |

|---|---|

| Multi-stakeholder collaboration in LL activities | 42(89%) |

| Aimed at innovation | 40(85%) |

| Co-creation as a central process | 37(79%) |

| LL activities take place in real-life contexts and communities | 33(70%) |

| Aimed at formal learning | 27(57%) |

| Iterative approach | 21(45%) |

| Shared decision-making power among all actors | 10(21%) |

| Other | 5(11%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galway, L.P.; Levkoe, C.Z.; Portinga, R.L.W.; Milun, K. A Scoping Review Examining Governance, Co-Creation, and Social and Ecological Justice in Living Labs Literature. Challenges 2022, 13, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe13010001

Galway LP, Levkoe CZ, Portinga RLW, Milun K. A Scoping Review Examining Governance, Co-Creation, and Social and Ecological Justice in Living Labs Literature. Challenges. 2022; 13(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe13010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalway, Lindsay P., Charles Z. Levkoe, Rachel L. W. Portinga, and Kathryn Milun. 2022. "A Scoping Review Examining Governance, Co-Creation, and Social and Ecological Justice in Living Labs Literature" Challenges 13, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe13010001

APA StyleGalway, L. P., Levkoe, C. Z., Portinga, R. L. W., & Milun, K. (2022). A Scoping Review Examining Governance, Co-Creation, and Social and Ecological Justice in Living Labs Literature. Challenges, 13(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe13010001