Computer Simulation of the Natural Vibrations of a Rigidly Fixed Plate Considering Temperature Shock

Abstract

:1. Introduction

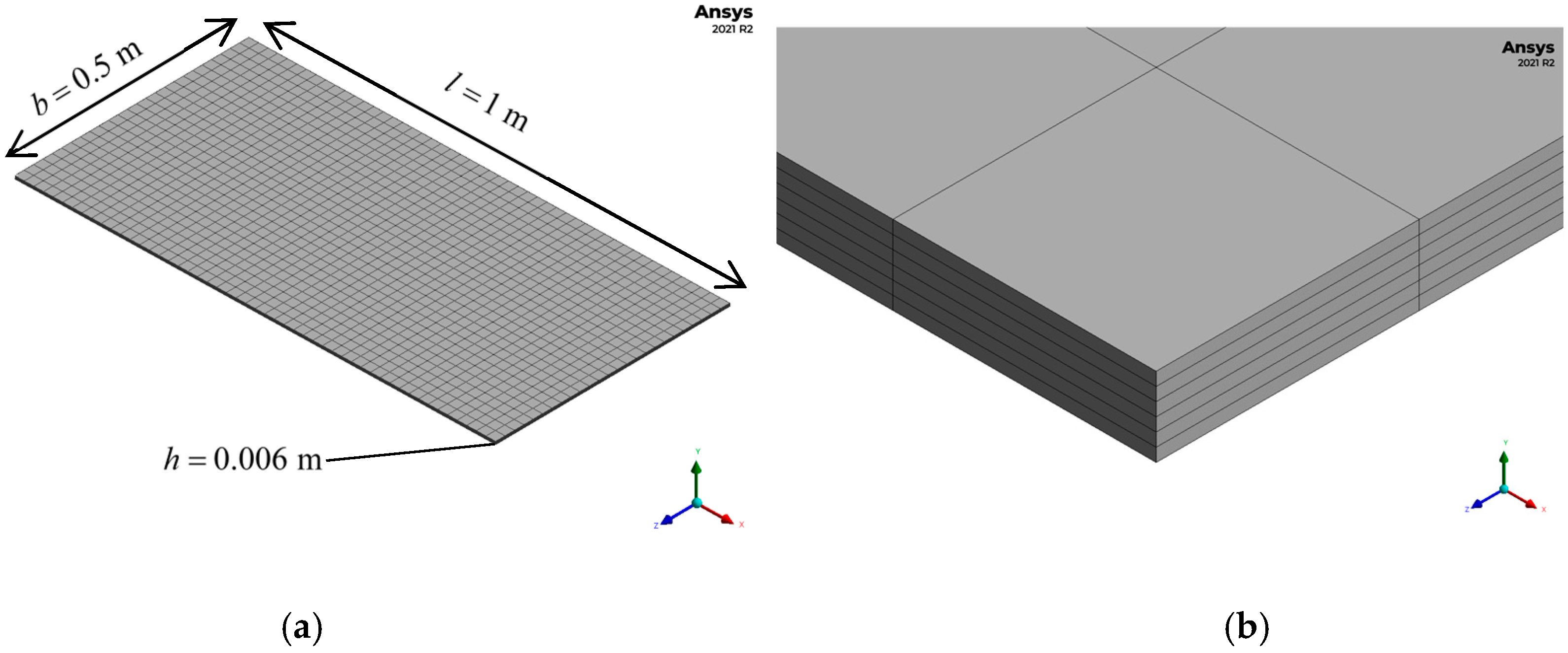

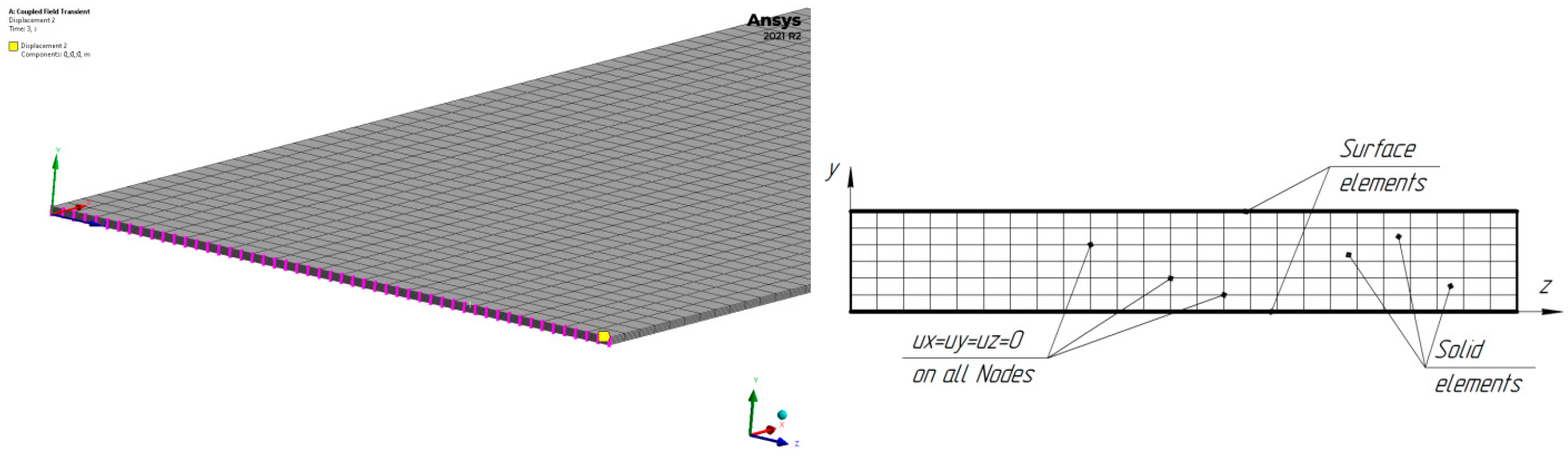

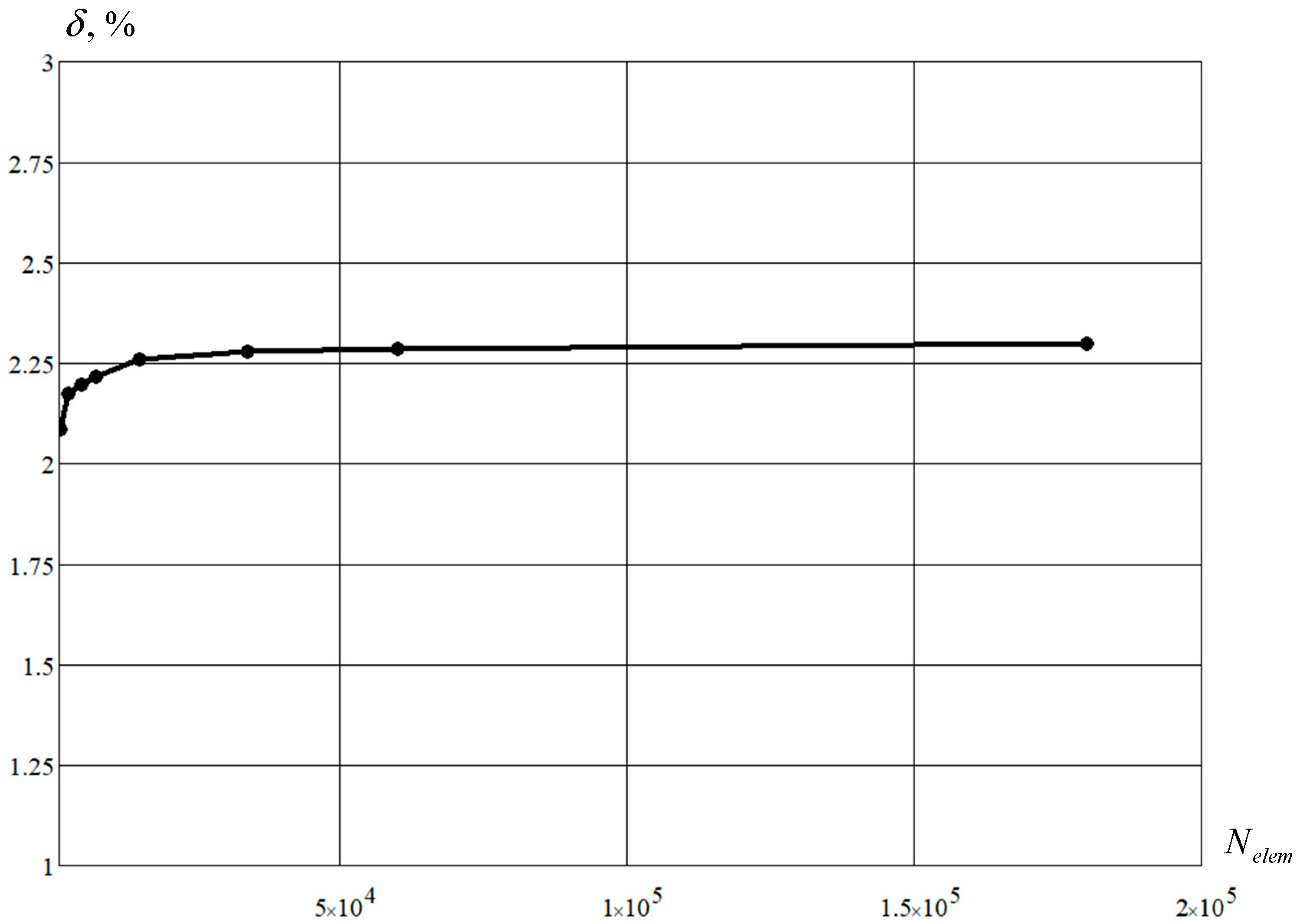

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- SOLID226 is a solid 20-node element of coupled analysis with options for a structural and thermal solution;

- -

- SURF152 is an element of the surface layer with one additional space node and options for setting properties through permanent elements (used to model the radiating surfaces of the plate).

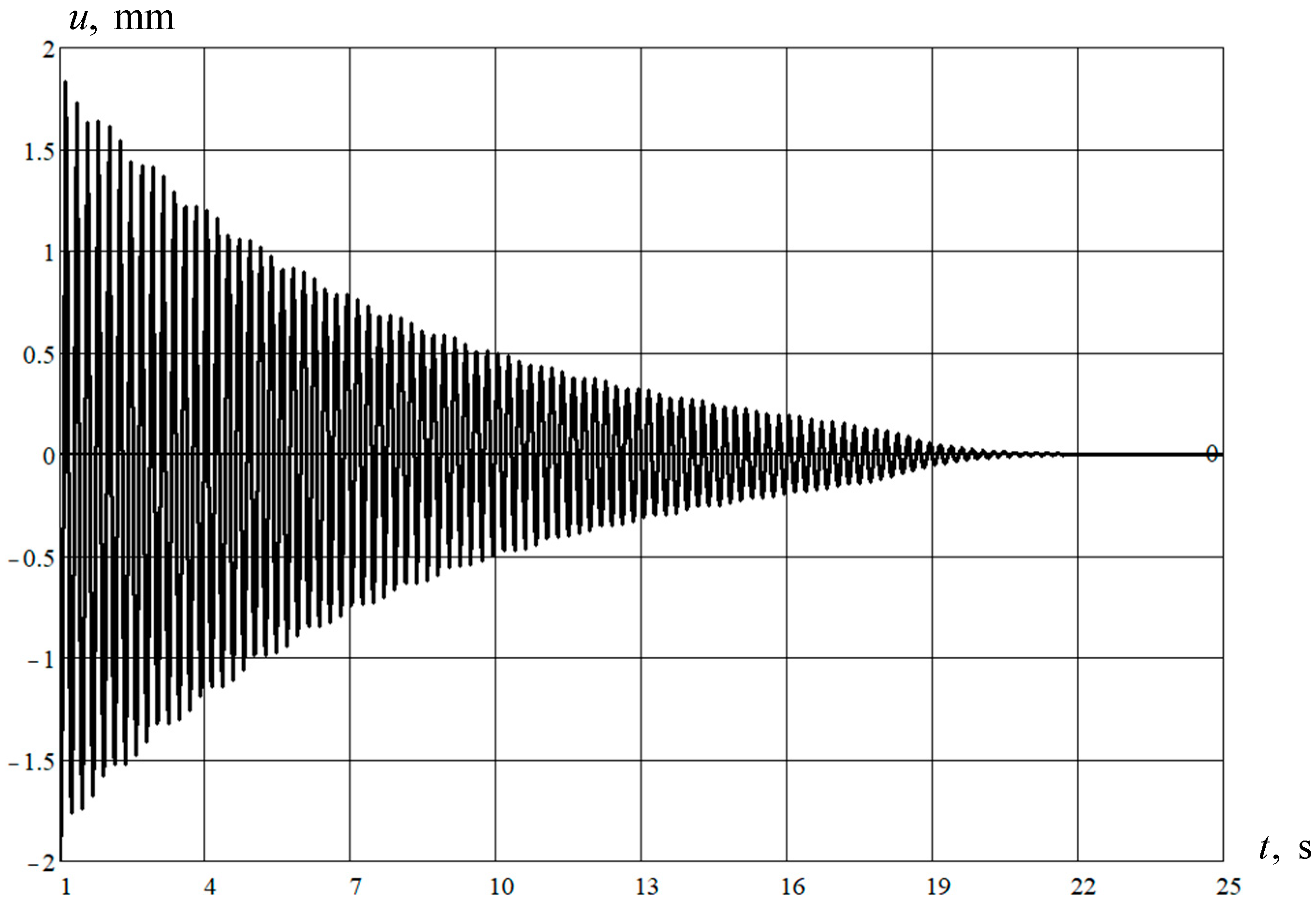

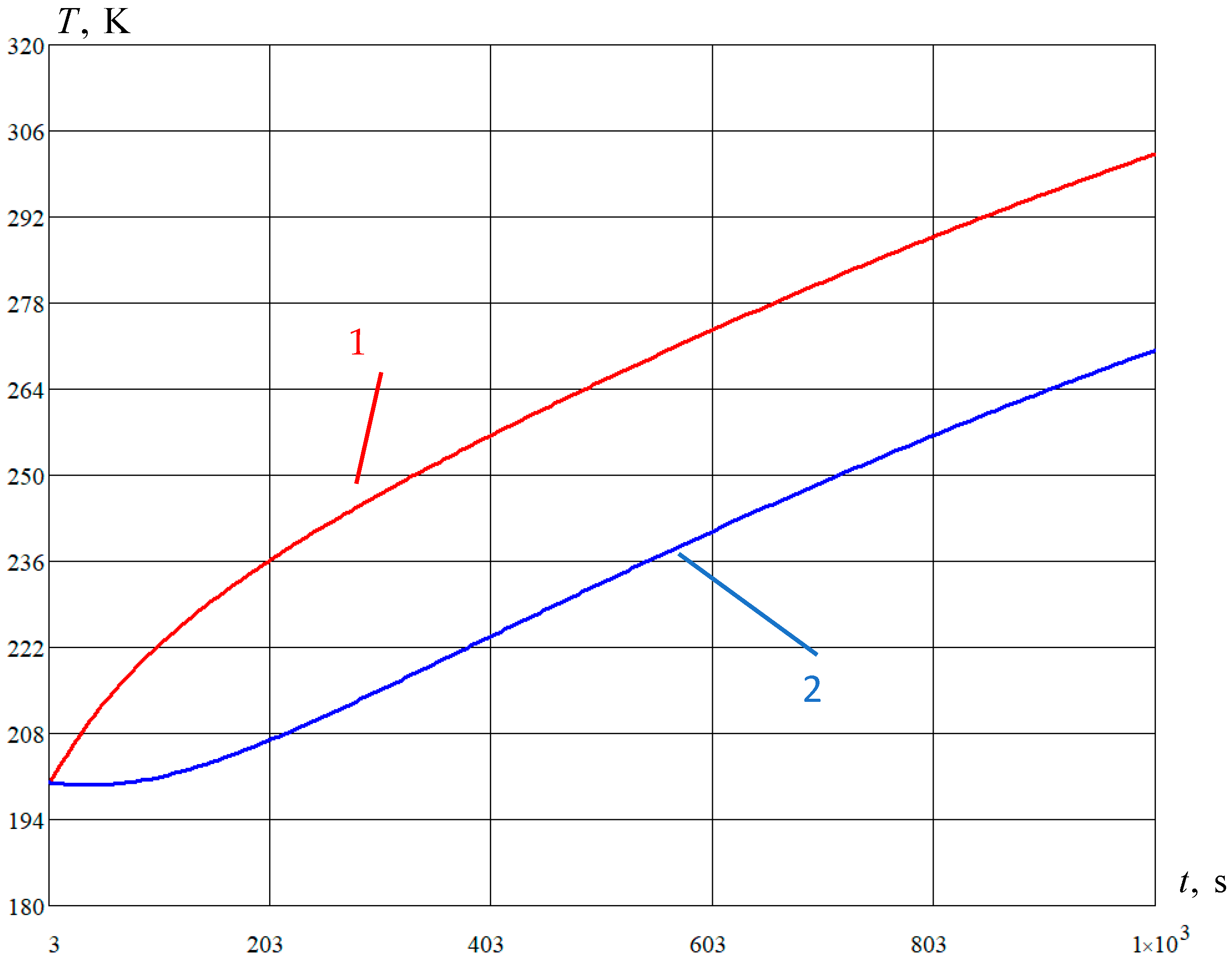

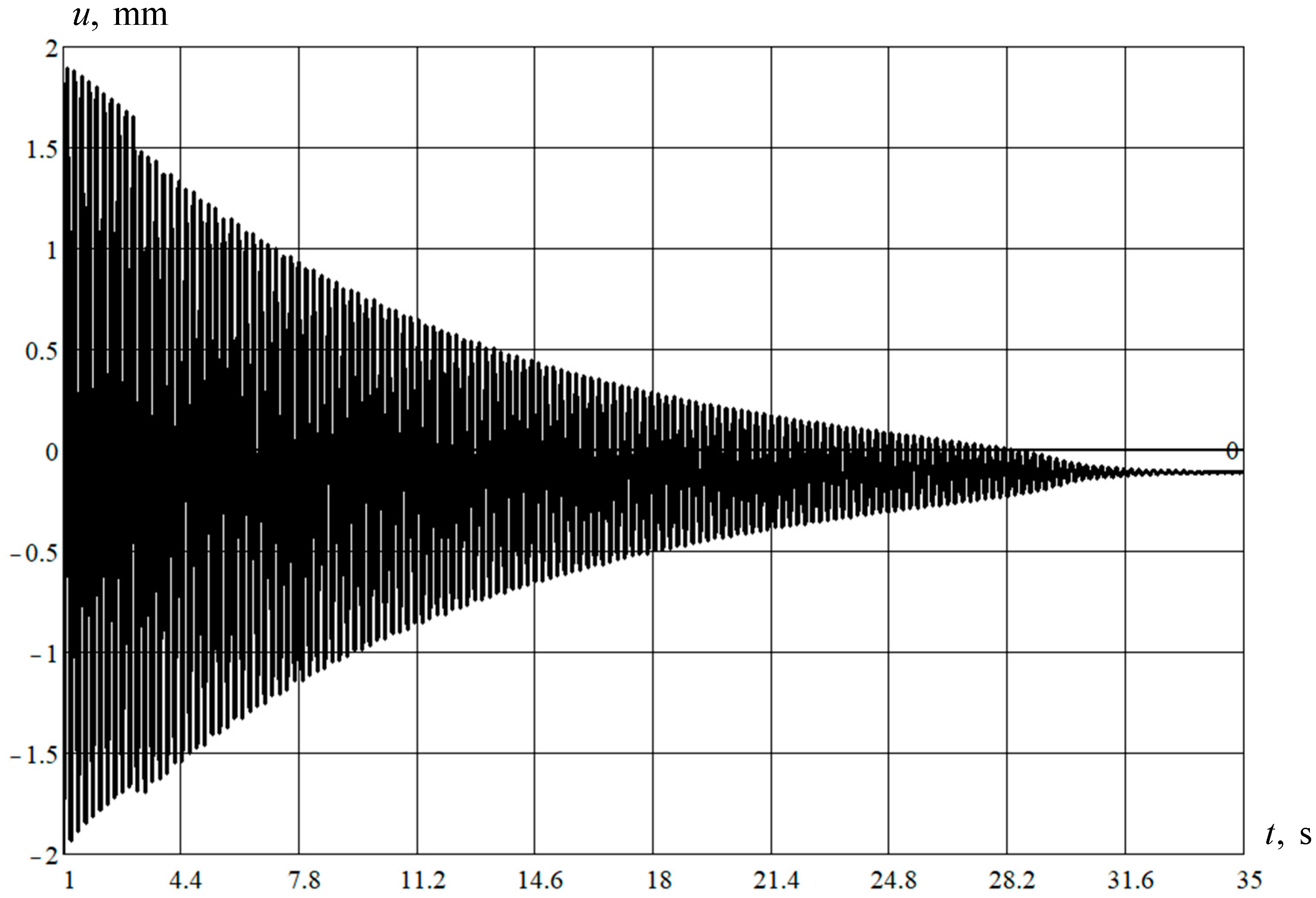

3. Results of Numerical Simulation

4. Discussion

- -

- The heat flux incident on the heated surface layer is equal to the sum of the flux radiating into the surrounding space and the flux leaving the plate due to thermal conductivity.

- -

- The heat flux at the shadow surface layer is equal to the flux radiating into the surrounding space. The fulfilment of these conditions ensures the constancy of the temperature of both surface layers. By neglecting the heat flows inside the plate, we can state the constancy of the temperature gradient across the plate thickness (the constant temperature difference between the heated and shadow surface layers of the plate). This means that there is a static distribution of internal thermal stresses within the plate. This stressed state (in the absence of other force effects) corresponds to a static equilibrium position (a curved equilibrium shape).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bormotov, A.N.; Orlov, D.I. Investigation of Perturbations Arising from Temperature Shock with a Symmetrical Arrangement of Flexible Elements of a Small Spacecraft. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedelinkov, A.; Nikolaeva, A.; Serdakova, V.; Khnyryova, E. Technologies for Increasing the Control Efficiency of Small Spacecraft with Solar Panels by Taking into Account Temperature Shock. Technologies 2024, 12, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Hao, S.; Li, H. Comparison of various thin-walled composite beam models for thermally induced vibrations of spacecraft boom. Compos. Struct. 2023, 320, 117163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, M.K.; Kiefer, S.H.; LaPointe, M.; LaCorte, P. On-orbit flight testing of the Roll-Out Solar Array. Acta Astronaut. 2021, 179, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, B.; White, S.; Wilder, N.; Gregory, T.; Douglas, M.; Takeda, R.; Mardesich, N.; Peterson, T.; Hillard, B.; Sharps, P.; et al. Next generation ultraflex solar array for NASA’s New Millennium Program Space Technology 8. In Proceedings of the IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 5–12 March 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichodziejewski, D.; Veal, G.; Helms, R.; Freeland, R.; Kruer, M. Inflatable Rigidizable Solar Array for Small Satellites. In Proceedings of the 44th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference, Norfolk, VA, USA, 7–10 April 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, B.R.; White, S.; LaPointe, M.; Kiefer, S.; LaCorte, P.; Banik, J.; Chapman, D.; Merrill, J. International Space Station (ISS) Roll-Out Solar Array (ROSA) Spaceflight Experiment Mission and Results. In Proceedings of the IEEE 7th World Conference on Photovoltaic Energy Conversion (WCPEC) (A Joint Conference of 45th IEEE PVSC, 28th PVSEC & 34th EU PVSEC), Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 10–15 June 2018; pp. 3522–3529. [Google Scholar]

- Rush, B.P.; Mages, D.M.; Vaughan, A.T.; Bellerose, J.; Bhaskaran, S. Optical navigation for the DART mission. In Proceedings of the 33rd AAS/AIAA Space Flight Mechanics Meeting, Austin, TX, USA, 14–19 January 2023; p. AAS 23-234. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X.; Wu, Y.; Yuan, Q.; He, J.; Zhou, C.; Shen, J. Characteristic Study of a Typical Satellite Solar Panel under Mechanical Vibrations. Micromachines 2024, 15, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo, L.O.; Giacomuzzo, C.; Francesconi, A. Fragments analysis of an hypervelocity impact experiment on a solar array. Acta Astronaut. 2024, 214, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahar, S.; Yadav, D.K. Retrospection and investigation of ANN-based MPPT technique in comparison with soft computing-based MPPT techniques for PV solar and wind energy generation system. Int. J. Math. Model. Numer. Optim. 2024, 14, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, G.-S.; Park, J.-H.; Park, S.-W.; Oh, H.-U. Development of a Passive Vibration Damping Structure for Large Solar Arrays Using a Superelastic Shape Memory Alloy with Multi-Layered Viscous Lamination. Aerospace 2025, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundipe, O.; Okwandu, A.; Abdulwaheed, S.A. Recent advances in solar photovoltaic technologies: Efficiency, materials, and applications. GSC Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 20, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, W. Vibration control for the solar panels of spacecraft: Innovation methods and potential approaches. Int. J. Mech. Syst. Dyn. 2023, 3, 300–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Wang, S.; Xia, H.; Ma, G. Dynamic Modeling and Control for a Double-State Microgravity Vibration Isolation System. Microgravity Sci. Technol. 2023, 35, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneeva, A.S. Analysis of the requirements for microaccelerations and the design appearance of a small spacecraft for technological purposes. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 458, 03006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneeva, A.S.; Bratkova, M.E.; Maslova, U.V. Model of a microgravity platform based on the mechanical principle of operation. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 531, 01009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeepkumar, M.S.; Kathirvel, A.; Ghosh, S.; Sudakar, C. Cs2AgBiBr6 and related Halide double perovskite porous single crystals. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanchour, K.M.; Benahmed, B. Two reduced non-smooth Newton’s methods for discretised state constrained optimal control problem governed by advection-diffusion equation. Int. J. Math. Model. Numer. Optim. 2023, 13, 147–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubimova, T.P.; Lobova, E.O. The Influence of Gravity Modulation on a Stability of Plane-Parallel Convective Flow in a Vertical Fluid Layer with Heat Sources. Microgravity Sci. Technol. 2024, 36, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Hablani, H.B. Satellite Payload Motion for Remote Sensing. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2014, 47, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Wu, Y. Improved YOLO-V3 with DenseNet for Multi-Scale Remote Sensing Target Detection. Sensors 2020, 20, 4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khudhur, H.M.; Fawze, A.A.M. An improved conjugate gradient method for solving unconstrained optimisation and image restoration problems. Int. J. Math. Model. Numer. Optim. 2023, 13, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Q. Torque-Limited Attitude Control for Rigid Spacecraft with Motion Constraints. In Proceedings of the 40th Chinese Control Conference, Shanghai, China, 26–28 July 2021; pp. 7724–7729. [Google Scholar]

- Rawat, A.K.; Deep, G.; Dhiman, N.; Chauhan, A. Convergence analysis and an efficient numerical technique for the solution of Benjamin Bona Mahony partial differential equation. Int. J. Math. Model. Numer. Optim. 2023, 13, 105–122. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Wang, S.; Wang, G.; Ma, G. Hierarchical Control for Microgravity Vibration Isolation System: Collision Avoidance and Execution Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 60, 6084–6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Hou, M.; Duan, G.; Hao, M. Adaptive dynamic surface asymptotic tracking control of uncertain strict-feedback systems with guaranteed transient performance and accurate parameter estimation. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control. 2022, 32, 6829–6848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangavel, K.; Parisse, M.; Marzocca, P. Modelization of Thermally Induced Jitter in an Orbiting Slender Structure. Adv. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 1, 525–541. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, D.; Chen, S.; Eltaher, M.A. Thermally Induced Vibration of a Flexible Plate with Enhanced Active Constrained Layer Damping. Aerospace 2024, 11, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Cao, D.Q. Dynamic Modeling and Attitude–Vibration Cooperative Control for a Large-Scale Flexible Spacecraft. Actuators 2023, 12, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.-X.; Liu, W.; Fan, C.-Z. Dynamic Characteristics of Satellite Solar Arrays under the Deployment Shock in Orbit. Shock. Vib. 2018, 2018, 6519748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Gao, W.; Fan, C.; Xiang, Z.; Du, C. Experimental study on thermally induced vibration of flexible solar cell wing simulator. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2882, 012068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Sun, S.; Cao, D.Q.; Liu, X. Thermal-structural analysis for flexible spacecraft with single or double solar panels: A comparison study. Acta Astronaut. 2019, 154, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, T.K.; Simple, K.R.; Venkatraman, K. Mathematical Models for the Dynamics Of Spacecraft With Deployed Solar Panels. J. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2014, 66, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.-E.; Kim, J.-H. Thermally Induced Vibrations of Spinning Thin-Walled Composite Beam. AIAA J. 2003, 41, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, J.; Yu, X.; Yu, J. Adaptive fuzzy robust H∞ control for motion and vibration suppression of fully flexible-link space robots. J. Comput. Methods Sci. Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Cao, D.Q.; Tan, X. Studies on global analytical mode for a three-axis attitude stabilized spacecraft by using the Rayleigh–Ritz method. Arch. Appl. Mech. 2016, 86, 1927–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yu, J.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, H.; Chen, S.; Zhang, L. Optimization Design for Support Points of the Body-Mounted Solar Panel. Aerospace 2025, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriwastav, N.; Barnwal, A.K. Numerical solution of Lane-Emden pantograph delay differential equation: Stability and convergence analysis. Int. J. Math. Model. Numer. Optim. 2023, 13, 64–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyushin, M.; Maksimenko, M.; Tikhonov, A.A. Electrodynamic Attitude Stabilization of a Spacecraft in an Elliptical Orbit. Aerospace 2024, 11, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolandi, H.; Abrehdari, S. Precise Autonomous Orbit Maintenance of a Low Earth Orbit Satellite. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2018, 31, 04018034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorghofer, N.; Khatiwala, S. Semi-implicit Solver for the Heat Equation with Stefan–Boltzmann Law Boundary Condition. Planet. Sci. J. 2024, 5, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsofen, S.Y.; Wu, R.; Grushin, I.A.; Speranskii, K.A.; Petrov, A.A. Texture and Anisotropy of the Mechanical Properties of MA2-1, MA14, and Mg–5Li–3Al Alloys. Russ. Metall. Met. 2022, 2022, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, V.; Askenazi, A. Building Better Products with Finite Element Analysis; OnWord Press: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.H.; Yamasaki, M.; Murozono, M. Experimental Verification of Thermal Structural Responses of a Flexible Rolled-Up Solar Array. Trans. Jpn. Soc. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 2013, 56, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmetov, R.; Filatov, A.; Khalilov, R.; Raube, S.; Borisov, M.; Salmin, V.; Tkachenko, I.; Safronov, S.; Ivanushkin, M. “AIST-2D”: Results of flight tests and application of earth remote sensing data for solving thematic problems. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2023, 26, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erisov, Y.; Kuzin, A.; Sedelnikov, A. An Analytical Model for the Plastic Bending of Anisotropic Sheet Materials, Incorporating the Strain-Hardening Effect. Technologies 2024, 12, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voropay, A.V.; Grishakin, V. Viscous friction modelling in material of a plate under its non-stationary loading with differential and integral operators. Trudy MAI 2019, 109, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, M.V. Vibration of rectangular and skew cantilever plates. J. Appl. Mech. 1951, 18, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Aramberria, J.; Pardoa, D.; Paszynskic, M.; Collierd, N.; Dalcine, L.; Calo, V.M. On Round-off Error for Adaptive Finite Element Methods. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2012, 9, 1474–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.-H.; Chae, J.-S.; Park, T.-W.; Han, S.-W.; Chai, J.-B.; Seo, H.-S. Solar Panel Deployment Analysis of a Satellite System. JSME Int. J. Ser. C 2003, 46, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, M.N.; Ugheoke, B.I.; Nwachukwu, D.O. Modeling and simulation of the kinematic behavior of the deployment mechanism of solar array for a 1-U CubeSat. Eng. Rep. 2022, 5, e12610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J.D.; Thornton, E.A. Thermally Induced Dynamics of Satellite Solar Panels. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2000, 37, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Shen, Z. Thermoelastic–structural dynamics analysis of a satellite with composite thin-walled boom. Acta Mech. 2022, 234, 1259–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suslov, A.V.; Yaroslavkina, E.E. Study of the influence of temperature stresses to natural vibrations of the plates. Vestnik of Samara University. Nat. Sci. Ser. 2024, 30, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Designation | Value | Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plate material | - | MA2 [43] | - |

| Density | 1780 | ||

| Young’s modulus | 4 × 1010 | ||

| Shear modulus | 1.6 × 1010 | ||

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.3 | - | |

| Plate length | 1 | ||

| Plate width | 0.5 | ||

| Plate thickness | 0.006 | ||

| Rayleigh stiffness-weighted damping constant | 0.0001 | s | |

| Initial deflection of the free edge | 0.002 |

| Parameter | Designation | Value | Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal conductivity | 40 | ||

| Stefan–Boltzmann coefficient | 5.67 × 10−8 | ||

| Heat flux | 1400 | ||

| Ambient temperature | 3 | ||

| Initial temperature of the plate | 200 | ||

| Emissivity | 0.8 | - | |

| Specific heat | 1130.4 | ||

| Coefficient of linear expansion | 26 × 10−6 | ||

| The moment of temperature shock | 3 | s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sedelnikov, A.; Glushkov, S.; Evtushenko, M.; Skvortsov, Y.; Nikolaeva, A. Computer Simulation of the Natural Vibrations of a Rigidly Fixed Plate Considering Temperature Shock. Computation 2025, 13, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation13020049

Sedelnikov A, Glushkov S, Evtushenko M, Skvortsov Y, Nikolaeva A. Computer Simulation of the Natural Vibrations of a Rigidly Fixed Plate Considering Temperature Shock. Computation. 2025; 13(2):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation13020049

Chicago/Turabian StyleSedelnikov, Andry, Sergey Glushkov, Maksim Evtushenko, Yurii Skvortsov, and Alexandra Nikolaeva. 2025. "Computer Simulation of the Natural Vibrations of a Rigidly Fixed Plate Considering Temperature Shock" Computation 13, no. 2: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation13020049

APA StyleSedelnikov, A., Glushkov, S., Evtushenko, M., Skvortsov, Y., & Nikolaeva, A. (2025). Computer Simulation of the Natural Vibrations of a Rigidly Fixed Plate Considering Temperature Shock. Computation, 13(2), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation13020049