Extracellular Vesicle-Based Therapeutics for Heart Repair

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Extracellular Vesicles

2.1. Classification

2.2. Biology

2.3. Mechanism of Action

2.4. Separation and Characterization of Extracellular Vesicles

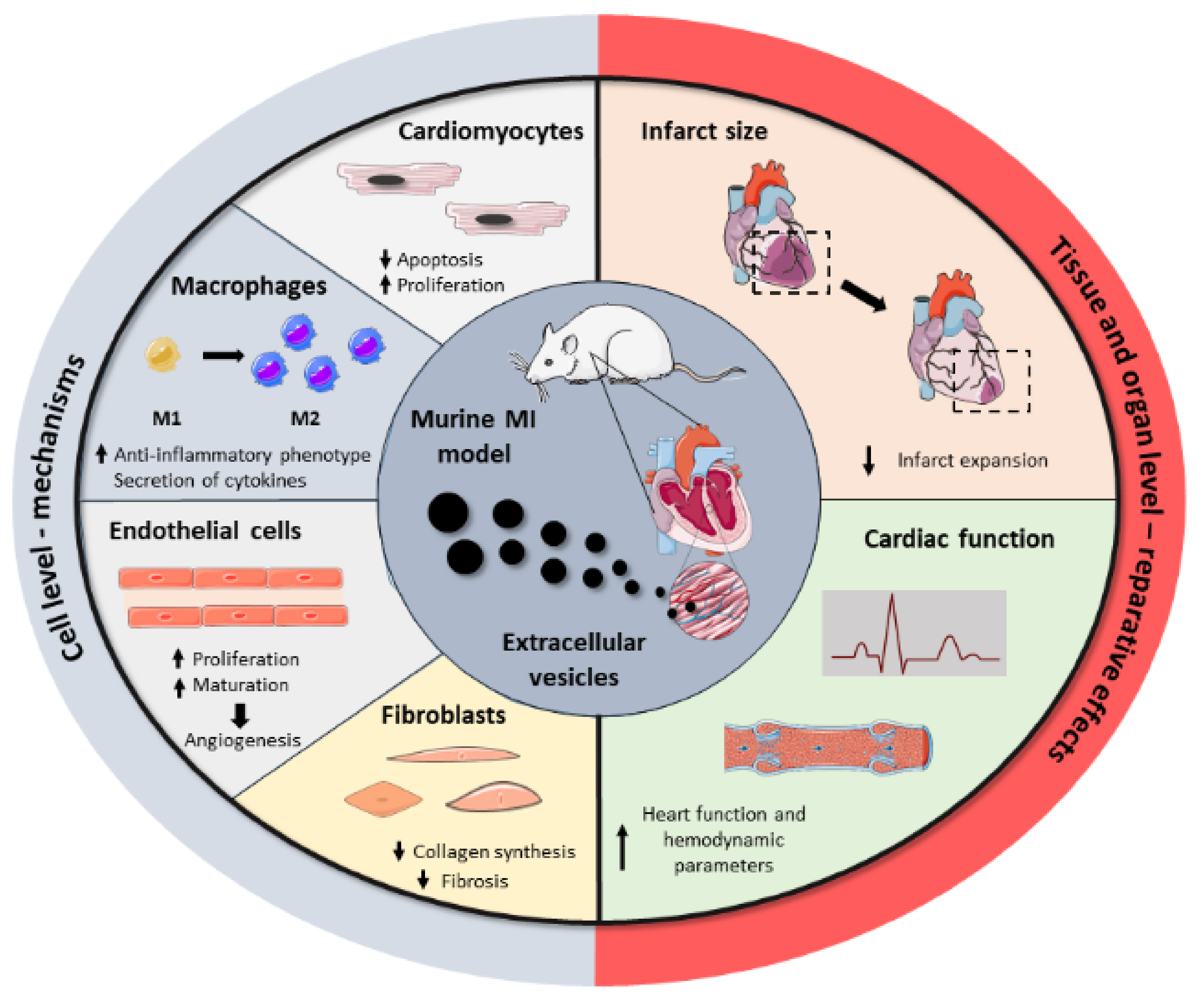

3. Potential Applications of Extracellular Vesicles as Therapeutic Agents in Myocardial Infarction

3.1. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

3.2. Cardiac Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

3.2.1. Cardiosphere-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

3.2.2. Cardiac Progenitor Cell-Derived EVs

3.3. Embryonic and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived EVs

3.3.1. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived EVs

3.3.2. Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived EVs

4. The Use of Extracellular Vesicles as a New Class of Drug Delivery System

4.1. Advantages of Using Extracellular Vesicles as Delivery Vehicles

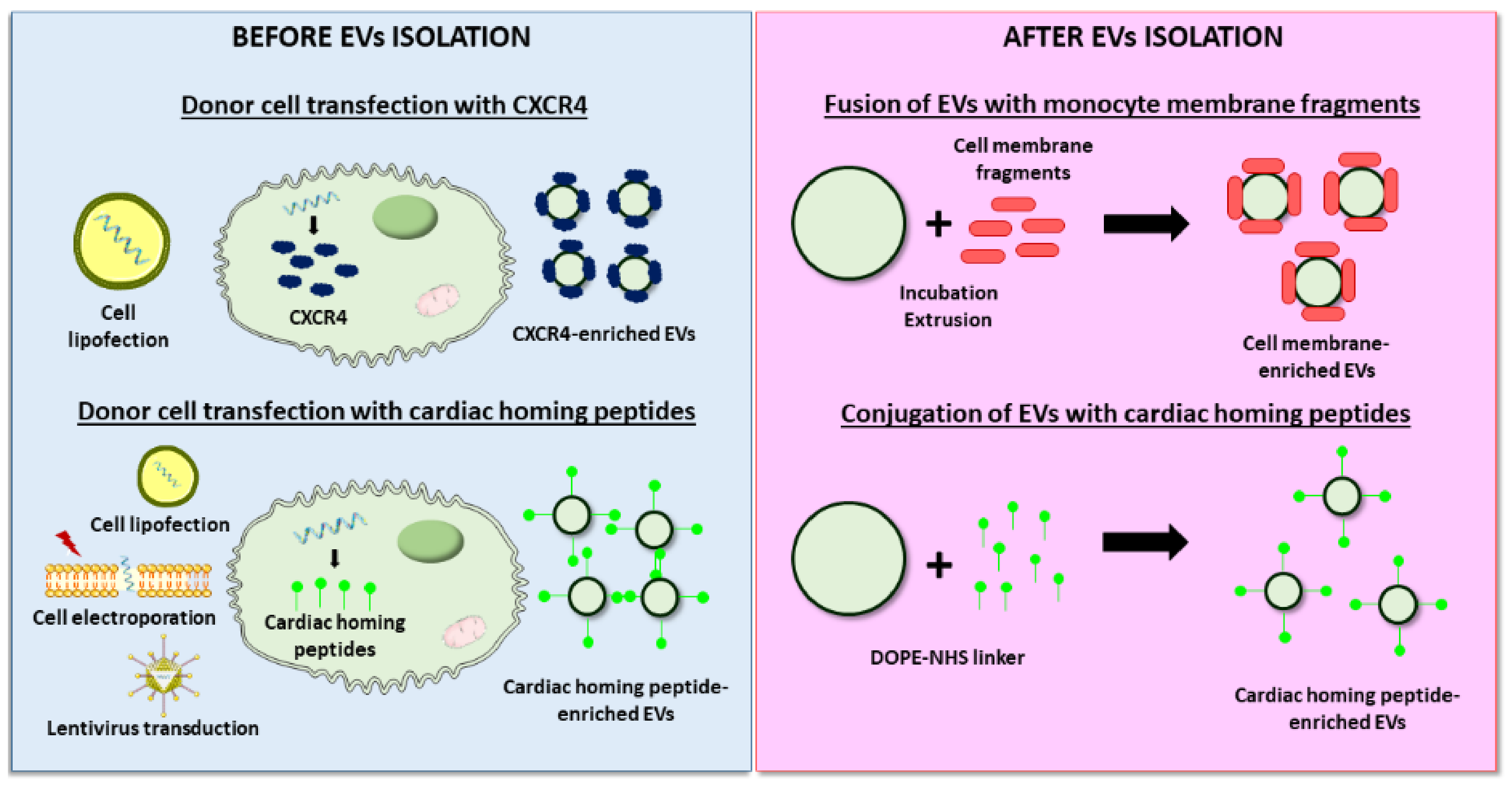

4.2. Bioengineered EVs for Cardiac Delivery

4.2.1. Cargo Loading

4.2.2. Improved Targeting to the Cardiac Tissue

5. Challenges and Future Directions of Extracellular Vesicle-Based Therapies for Cardiac Repair

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 4 December 2020).

- Andreadou, I.; Cabrera-Fuentes, H.A.; Devaux, Y.; Frangogiannis, N.G.; Frantz, S.; Guzik, T.; Liehn, E.; Pedrosa da Costa Gomes, C.; Schulz, R.; Hausenloy, D.J. Immune cells as targets for cardioprotection: New players and novel therapeutic opportunities. Cardiovasc. Res. 2019, 115, 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abbafati, C.; Machado, D.B.; Cislaghi, B.; Salman, O.M.; Karanikolos, M.; McKee, M.; Abbas, K.M.; Brady, O.J.; Larson, H.J.; Trias-Llimós, S.; et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burden, G.; Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Banach, M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990–2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Abreu, R.C.; Fernandes, H.; da Costa Martins, P.A.; Sahoo, S.; Emanueli, C.; Ferreira, L. Native and bioengineered extracellular vesicles for cardiovascular therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marbán, E. A mechanistic roadmap for the clinical application of cardiac cell therapies. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marbán, E. The Secret Life of Exosomes: What Bees Can Teach Us About Next-Generation Therapeutics. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigorian Shamagian, L.; Madonna, R.; Taylor, D.; Climent, A.M.; Prosper, F.; Bras-Rosario, L.; Bayes-Genis, A.; Ferdinandy, P.; Fernández-Avilés, F.; Izpisua Belmonte, J.C.; et al. Perspectives on Directions and Priorities for Future Preclinical Studies in Regenerative Medicine. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 938–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menasché, P. Cell therapy trials for heart regeneration—Lessons learned and future directions. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1535750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Whittaker, T.E.; Nagelkerke, A.; Nele, V.; Kauscher, U.; Stevens, M.M. Experimental artefacts can lead to misattribution of bioactivity from soluble mesenchymal stem cell paracrine factors to extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1807674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluijter, J.P.G.; Davidson, S.M.; Boulanger, C.M.; Buzás, E.I.; De Kleijn, D.P.V.; Engel, F.B.; Giricz, Z.; Hausenloy, D.J.; Kishore, R.; Lecour, S.; et al. Extracellular vesicles in diagnostics and therapy of the ischaemic heart: Position Paper from the Working Group on Cellular Biology of the Heart of the European Society of Cardiology. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.Y.; Lee, C.K.; Huang, C.; Ou, Y.H.; Charles, C.J.; Richards, A.M.; Neupane, Y.R.; Pavon, M.V.; Zharkova, O.; Pastorin, G.; et al. Extracellular vesicles in cardiovascular diseases: Alternative biomarker sources, therapeutic agents, and drug delivery carriers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martins-Marques, T.; Hausenloy, D.J.; Sluijter, J.P.G.; Leybaert, L.; Girao, H. Intercellular Communication in the Heart: Therapeutic Opportunities for Cardiac Ischemia. Trends Mol. Med. 2020, 27, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkach, M.; Théry, C. Communication by Extracellular Vesicles: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go. Cell 2016, 164, 1226–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghafarian, F.; Pashirzad, M.; Khazaei, M.; Rezayi, M.; Hassanian, S.M.; Ferns, G.A.; Avan, A. The clinical impact of exosomes in cardiovascular disorders: From basic science to clinical application. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 12226–12236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saludas, L.; Pascual-Gil, S.; Roli, F.; Garbayo, E.; Blanco-Prieto, M.J. Heart tissue repair and cardioprotection using drug delivery systems. Maturitas 2018, 110, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaie, J.; Rahbarghazi, R.; Pezeshki, M.; Mazhar, M.; Yekani, F.; Khaksar, M.; Shokrollahi, E.; Amini, H.; Hashemzadeh, S.; Sokullu, S.E.; et al. Cardioprotective role of extracellular vesicles: A highlight on exosome beneficial effects in cardiovascular diseases. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 21732–21745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tikhomirov, R.; Donnell, B.R.O.; Catapano, F.; Faggian, G.; Gorelik, J.; Martelli, F.; Emanueli, C. Exosomes: From Potential Culprits to New Therapeutic Promise in the Setting of Cardiac Fibrosis. Cells 2020, 9, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deb, A.; Gupta, S.; Mazumder, P.B. Exosomes: A new horizon in modern medicine. Life Sci. 2020, 118623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Niel, G.; D’Angelo, G.; Raposo, G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A.E.; Sneider, A.; Witwer, K.W.; Bergese, P.; Bhattacharyya, S.N.; Cocks, A.; Cocucci, E.; Erdbrügger, U.; Falcon-Perez, J.M.; Freeman, D.W.; et al. Biological membranes in EV biogenesis, stability, uptake, and cargo transfer: An ISEV position paper arising from the ISEV membranes and EVs workshop. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1684862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Konoshenko, M.Y.; Lekchnov, E.A.; Vlassov, A.V.; Laktionov, P.P. Isolation of Extracellular Vesicles: General Methodologies and Latest Trends. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skotland, T.; Sagini, K.; Sandvig, K.; Llorente, A. An emerging focus on lipids in extracellular vesicles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 159, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femminò, S.; Penna, C.; Margarita, S.; Comità, S.; Brizzi, M.F.; Pagliaro, P. Extracellular vesicles and cardiovascular system: Biomarkers and Cardioprotective Effectors. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2020, 135, 106790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesidou, D.; da Costa Martins, P.A.; de Windt, L.J.; Brittan, M.; Beqqali, A.; Baker, A.H. Extracellular Vesicle miRNAs in the Promotion of Cardiac Neovascularisation. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro, A.; Silva, A.M.; Teixeira, J.H.; Gonçalves, R.M.; Almeida, M.I.; Barbosa, M.A.; Santos, S.G. Extracellular vesicles: Intelligent delivery strategies for therapeutic applications. J. Control. Release 2018, 289, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, B.; Barros, E.R.; Hoenderop, J.G.J.; Rigalli, J.P. Recent advances in extracellular vesicles as drug delivery systems and their potential in precision medicine. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.; Raposo, G.; Théry, C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 30, 255–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Azimi, I.; Monteith, G.; Bebawy, M. Ca2+ mediates extracellular vesicle biogenesis through alternate pathways in malignancy. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boulanger, C.M.; Loyer, X.; Rautou, P.E.; Amabile, N. Extracellular vesicles in coronary artery disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, D.E.; Exner, T.; Ma, D.D.F.; Joseph, J.E. The majority of circulating platelet-derived microparticles fail to bind annexin V, lack phospholipid-dependent procoagulant activity and demonstrate greater expression of glycoprotein Ib. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 103, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Momen-Heravi, F.; Getting, S.J.; Moschos, S.A. Extracellular vesicles and their nucleic acids for biomarker discovery. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 192, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cesselli, D.; Parisse, P.; Aleksova, A.; Veneziano, C.; Cervellin, C.; Zanello, A.; Beltrami, A.P. Extracellular vesicles: How drug and pathology interfere with their biogenesis and function. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelli, A.E.; Larregina, A.T.; Shufesky, W.J.; Sullivan, M.L.G.; Stolz, D.B.; Papworth, G.D.; Zahorchak, A.F.; Logar, A.J.; Wang, Z.; Watkins, S.C.; et al. Endocytosis, intracellular sorting, and processing of exosomes by dendritic cells. Blood 2004, 104, 3257–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nazarenko, I.; Rana, S.; Baumann, A.; McAlear, J.; Hellwig, A.; Trendelenburg, M.; Lochnit, G.; Preissner, K.T.; Zöller, M. Cell surface tetraspanin Tspan8 contributes to molecular pathways of exosome-induced endothelial cell activation. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 1668–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christianson, H.C.; Svensson, K.J.; Van Kuppevelt, T.H.; Li, J.P.; Belting, M. Cancer cell exosomes depend on cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans for their internalization and functional activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 17380–17385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuentes, P.; Sesé, M.; Guijarro, P.J.; Emperador, M.; Sánchez-Redondo, S.; Peinado, H.; Hümmer, S.; Ramón, y. Cajal, S. ITGB3-mediated uptake of small extracellular vesicles facilitates intercellular communication in breast cancer cells. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonda, A.; Kabagwira, J.; Senthil, G.N.; Wall, N.R. Internalization of exosomes through receptor-mediated endocytosis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2019, 17, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feng, D.; Zhao, W.L.; Ye, Y.Y.; Bai, X.C.; Liu, R.Q.; Chang, L.F.; Zhou, Q.; Sui, S.F. Cellular internalization of exosomes occurs through phagocytosis. Traffic 2010, 11, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.R.; Ortiz, P.A. Dynamin2, clathrin, andlipid rafts mediate endocytosis of the apical Na/K/2Cl cotransporter NKCC2 in thick ascending limbs. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 37824–37834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nanbo, A.; Kawanishi, E.; Yoshida, R.; Yoshiyama, H. Exosomes Derived from Epstein-Barr Virus-Infected Cells Are Internalized via Caveola-Dependent Endocytosis and Promote Phenotypic Modulation in Target Cells. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 10334–10347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tian, T.; Zhu, Y.L.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Liang, G.F.; Wang, Y.Y.; Hu, F.H.; Xiao, Z.D. Exosome uptake through clathrin-mediated endocytosis and macropinocytosis and mediating miR-21 delivery. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 22258–22267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Montecalvo, A.; Larregina, A.T.; Shufesky, W.J.; Stolz, D.B.; Sullivan, M.L.G.; Karlsson, J.M.; Baty, C.J.; Gibson, G.A.; Erdos, G.; Wang, Z.; et al. Mechanism of transfer of functional microRNAs between mouse dendritic cells via exosomes. Blood 2012, 119, 756–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuana, Y.; Böing, A.N.; Grootemaat, A.E.; van der Pol, E.; Hau, C.M.; Cizmar, P.; Buhr, E.; Sturk, A.; Nieuwland, R. Handling and storage of human body fluids for analysis of extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, A.; Boilard, E.; Buzas, E.I.; Cheng, L.; Falcón-Perez, J.M.; Gardiner, C.; Gustafson, D.; Gualerzi, A.; Hendrix, A.; Hoffman, A.; et al. Considerations towards a roadmap for collection, handling and storage of blood extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patel, G.K.; Khan, M.A.; Zubair, H.; Srivastava, S.K.; Khushman, M.; Singh, S.; Singh, A.P. Comparative analysis of exosome isolation methods using culture supernatant for optimum yield, purity and downstream applications. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Takov, K.; Yellon, D.M.; Davidson, S.M. Comparison of small extracellular vesicles isolated from plasma by ultracentrifugation or size-exclusion chromatography: Yield, purity and functional potential. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Gong, M.; Hu, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, M.; Hu, X.; Aubert, D.; Zhu, S.; Wu, L.; et al. Quality and efficiency assessment of six extracellular vesicle isolation methods by nano-flow cytometry. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Pertierra, E.; Oliveira-Rodríguez, M.; Rivas, M.; Oliva, P.; Villafani, J.; Navarro, A.; Blanco-López, M.C.; Cernuda-Morollón, E. Characterization of plasma-derived extracellular vesicles isolated by different methods: A comparison study. Bioengineering 2019, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brennan, K.; Martin, K.; FitzGerald, S.P.; O’Sullivan, J.; Wu, Y.; Blanco, A.; Richardson, C.; Mc Gee, M.M. A comparison of methods for the isolation and separation of extracellular vesicles from protein and lipid particles in human serum. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Askeland, A.; Borup, A.; Østergaard, O.; Olsen, J.V.; Lund, S.M.; Christiansen, G.; Kristensen, S.R.; Heegaard, N.H.H.; Pedersen, S. Mass-spectrometry based proteome comparison of extracellular vesicle isolation methods: Comparison of ME-kit, size-exclusion chromatography, and high-speed centrifugation. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandham, S.; Su, X.; Wood, J.; Nocera, A.L.; Alli, S.C.; Milane, L.; Zimmerman, A.; Amiji, M.; Ivanov, A.R. Technologies and Standardization in Research on Extracellular Vesicles. Trends Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 1066–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böing, A.N.; van der Pol, E.; Grootemaat, A.E.; Coumans, F.A.W.; Sturk, A.; Nieuwland, R. Single-step isolation of extracellular vesicles by size-exclusion chromatography. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cointe, S.; Harti Souab, K.; Bouriche, T.; Vallier, L.; Bonifay, A.; Judicone, C.; Robert, S.; Armand, R.; Poncelet, P.; Albanese, J.; et al. A new assay to evaluate microvesicle plasmin generation capacity: Validation in disease with fibrinolysis imbalance. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pedersen, K.W.; Kierulf, B.; Neurauter, A. Specific and Generic Isolation of Extracellular Vesicles with Magnetic Beads. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1660, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.A.; van der Pol, E.; Bettin, B.A.; Carter, D.R.F.; Hendrix, A.; Lenassi, M.; Langlois, M.A.; Llorente, A.; van de Nes, A.S.; Nieuwland, R.; et al. Towards defining reference materials for measuring extracellular vesicle refractive index, epitope abundance, size and concentration. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1816641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cizmar, P.; Yuana, Y. Detection and Characterization of Extracellular Vesicles by Transmission and Cryo-Transmission Electron Microscopy. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1660, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cointe, S.; Judicone, C.; Robert, S.; Mooberry, M.J.; Poncelet, P.; Wauben, M.; Nieuwland, R.; Key, N.S.; Dignat-George, F.; Lacroix, R. Standardization of microparticle enumeration across different flow cytometry platforms: Results of a multicenter collaborative workshop. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2017, 15, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Görgens, A.; Bremer, M.; Ferrer-Tur, R.; Murke, F.; Tertel, T.; Horn, P.A.; Thalmann, S.; Welsh, J.A.; Probst, C.; Guerin, C.; et al. Optimisation of imaging flow cytometry for the analysis of single extracellular vesicles by using fluorescence-tagged vesicles as biological reference material. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Rond, L.; Van Der Pol, E.; Hau, C.M.; Varga, Z.; Sturk, A.; Van Leeuwen, T.G.; Nieuwland, R.; Coumans, F.A.W. Comparison of generic fluorescent markers for detection of extracellular vesicles by flow cytometry. Clin. Chem. 2018, 64, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lan, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, P.; Meng, Q.; Geng, Y.J.; Yu, X.Y.; et al. MiRNA-Sequence Indicates That Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Exosomes Have Similar Mechanism to Enhance Cardiac Repair. Biomed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 4150705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, X.; Hu, J.; Chen, F.; Qiao, S.; Sun, X.; Gao, L.; Xie, J.; Xu, B. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes attenuate myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury through miR-182-regulated macrophage polarization. Cardiovasc. Res. 2019, 115, 1205–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, R.; Zhang, F.; Chai, R.; Zhou, W.; Hu, M.; Liu, B.; Chen, X.; Liu, M.; Xu, Q.; Liu, N.; et al. Exosomes derived from pro-inflammatory bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells reduce inflammation and myocardial injury via mediating macrophage polarization. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 7617–7631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Huang, P.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.; Xu, J.; Xu, J.; Xiong, Y.; Chen, G.; Qian, H.; Jin, C.; Yu, Y.; et al. Combinatorial treatment of acute myocardial infarction using stem cells and their derived exosomes resulted in improved heart performance. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, P.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.; Tian, X.; Xu, J.; Xu, J.; Xiong, Y.; Chen, G.; Qian, H.; Jin, C.; et al. Atorvastatin enhances the therapeutic efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes in acute myocardial infarction via up-regulating long non-coding RNA H19. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Chen, C.; Yang, D.; Liao, Q.; Luo, H.; Wang, X.; Zhou, F.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Zeng, C.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells-derived extracellular vesicles, via miR-210, improve infarcted cardiac function by promotion of angiogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 2085–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Lu, K.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, Q.; Shen, J.; Lin, Y.; Xiang, P.; Tang, Y.; Hu, X.; et al. Myocardial reparative functions of exosomes from mesenchymal stem cells are enhanced by hypoxia treatment of the cells via transferring microRNA-210 in an nSMase2-dependent way. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 1659–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, L.; Jin, X.; Hu, C.F.; Li, R.; Zhou, Z.; Shen, C.X. Exosomes Derived from Mesenchymal Stem Cells Rescue Myocardial Ischaemia/Reperfusion Injury by Inducing Cardiomyocyte Autophagy Via AMPK and Akt Pathways. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 43, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luther, K.M.; Haar, L.; McGuinness, M.; Wang, Y.; Lynch IV, T.L.; Phan, A.; Song, Y.; Shen, Z.; Gardner, G.; Kuffel, G.; et al. Exosomal miR-21a-5p mediates cardioprotection by mesenchymal stem cells. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2018, 119, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.P.; Tian, T.; Wang, J.Y.; He, J.N.; Chen, T.; Pan, M.; Xu, L.; Zhang, H.X.; Qiu, X.T.; Li, C.C.; et al. Hypoxia-elicited mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes facilitates cardiac repair through miR-125b-mediated prevention of cell death in myocardial infarction. Theranostics 2018, 8, 6163–6177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.S.; Shao, K.; Liu, C.W.; Li, C.J.; Yu, B.T. Hypoxic preconditioning BMSCs-exosomes inhibit cardiomyocyte apoptosis after acute myocardial infarction by upregulating MicroRNA-24. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 6691–6699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, S.; Zhou, X.; Ge, Z.; Song, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, D. Exosomes from adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate cardiac damage after myocardial infarction by activating S1P/SK1/S1PR1 signaling and promoting macrophage M2 polarization. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2019, 114, 105564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; He, Z.; Liang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J. Exosomes from Adipose-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Protect the Myocardium Against Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury Through Wnt/b-Catenin Signaling Pathway. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2017, 70, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, L.; Xu, R.; Sun, X.; Duan, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Qian, H.; Zhu, W.; Xu, W. Safety evaluation of exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cell. Cytotherapy 2016, 18, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Yang, Y.; Guo, Q.; Gao, Q.; Ding, Y.; Wang, H.; Xu, W.; Yu, B.; Wang, M.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Exosomes Derived from Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promote Fibroblast-to-Myofibroblast Differentiation in Inflammatory Environments and Benefit Cardioprotective Effects. Stem Cells Dev. 2019, 28, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.L.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Sun, L.; Shi, Y.; Li, Z.Q.; Zhao, X.D.; Xu, C.G.; Ji, H.G.; Wang, M.; Xu, W.R.; et al. Exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells improve myocardial repair via upregulation of Smad7. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 41, 3063–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, C.; Shen, Y.; Ma, G.; Liu, Y.; Cai, J.; Kim, I.M.; Weintraub, N.L.; Liu, N.; Tang, Y. Transplantation of Cardiac Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Promotes Repair in Ischemic Myocardium. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2018, 11, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallet, R.; Dawkins, J.; Valle, J.; Simsolo, E.; De Couto, G.; Middleton, R.; Tseliou, E.; Luthringer, D.; Kreke, M.; Smith, R.R.; et al. Exosomes secreted by cardiosphere-derived cells reduce scarring, attenuate adverse remodelling, and improve function in acute and chronic porcine myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- López, E.; Blázquez, R.; Marinaro, F.; Álvarez, V.; Blanco, V.; Báez, C.; González, I.; Abad, A.; Moreno, B.; Sánchez-Margallo, F.M.; et al. The Intrapericardial Delivery of Extracellular Vesicles from Cardiosphere-Derived Cells Stimulates M2 Polarization during the Acute Phase of Porcine Myocardial Infarction. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2020, 16, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Couto, G.; Gallet, R.; Cambier, L.; Jaghatspanyan, E.; Makkar, N.; Dawkins, J.F.; Berman, B.P.; Marbán, E. Exosomal MicroRNA Transfer into Macrophages Mediates Cellular Postconditioning. Circulation 2017, 136, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseliou, E.; Fouad, J.; Reich, H.; Slipczuk, L.; De Couto, G.; Aminzadeh, M.; Middleton, R.; Valle, J.; Weixin, L.; Marbán, E. Fibroblasts Rendered Antifibrotic, Antiapoptotic, and Angiogenic by Priming with Cardiosphere-Derived Extracellular Membrane Vesicles. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maring, J.A.; Lodder, K.; Mol, E.; Verhage, V.; Wiesmeijer, K.C.; Dingenouts, C.K.E.; Moerkamp, A.T.; Deddens, J.C.; Vader, P.; Smits, A.M.; et al. Cardiac Progenitor Cell–Derived Extracellular Vesicles Reduce Infarct Size and Associate with Increased Cardiovascular Cell Proliferation. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2019, 12, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gray, W.D.; French, K.M.; Ghosh-Choudhary, S.; Maxwell, J.T.; Brown, M.E.; Platt, M.O.; Searles, C.D.; Davis, M.E. Identification of Therapeutic Covariant MicroRNA Clusters in Hypoxia-Treated Cardiac Progenitor Cell Exosomes Using Systems Biology. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barile, L.; Cervio, E.; Lionetti, V.; Milano, G.; Ciullo, A.; Biemmi, V.; Bolis, S.; Altomare, C.; Matteucci, M.; Di Silvestre, D.; et al. Cardioprotection by cardiac progenitor cell-secreted exosomes: Role of pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 992–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El Harane, N.; Kervadec, A.; Bellamy, V.; Pidial, L.; Neametalla, H.J.; Perier, M.C.; Lima Correa, B.; Thiébault, L.; Cagnard, N.; Duché, A.; et al. Acellular therapeutic approach for heart failure: In vitro production of extracellular vesicles from human cardiovascular progenitors. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 1835–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El Harane, N.; Correa, B.L.; Gomez, I.; Hocine, H.R.; Vilar, J.; Desgres, M.; Bellamy, V.; Keirththana, K.; Guillas, C.; Perotto, M.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles from Human Cardiovascular Progenitors Trigger a Reparative Immune Response in Infarcted Hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 2021, 117, 292–307. [Google Scholar]

- Adamiak, M.; Cheng, G.; Bobis-Wozowicz, S.; Zhao, L.; Kedracka-Krok, S.; Samanta, A.; Karnas, E.; Xuan, Y.T.; Skupien-Rabian, B.; Chen, X.; et al. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC)-derived extracellular vesicles are safer and more effective for cardiac repair than iPSCs. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Wang, J.; Tan, W.L.W.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, Q.; Yu, X.; Tan, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, P.; et al. Extracellular vesicles from human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiovascular progenitor cells promote cardiac infarct healing through reducing cardiomyocyte death and promoting angiogenesis. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kervadec, A.; Bellamy, V.; El Harane, N.; Arakélian, L.; Vanneaux, V.; Cacciapuoti, I.; Nemetalla, H.; Périer, M.C.; Toeg, H.D.; Richart, A.; et al. Cardiovascular progenitor-derived extracellular vesicles recapitulate the beneficial effects of their parent cells in the treatment of chronic heart failure. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2016, 35, 795–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.; Nickoloff, E.; Abramova, T.; Johnson, J.; Verma, S.K.; Krishnamurthy, P.; Mackie, A.R.; Vaughan, E.; Garikipati, V.N.S.; Benedict, C.; et al. Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Promote Endogenous Repair Mechanisms and Enhance Cardiac Function Following Myocardial Infarction. Circ. Res. 2015, 117, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guo, Y.; Yu, Y.; Hu, S.; Chen, Y.; Shen, Z. The therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells for cardiovascular diseases. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, C.P.; Bareja, A.; Gomez, J.A.; Dzau, V.J. Emerging concepts in paracrine mechanisms in regenerative cardiovascular medicine and biology. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zaruba, M.M.; Franz, W.M. Role of the SDF-1-CXCR4 axis in stem cell-based therapies for ischemic cardiomyopathy. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2010, 10, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Harvey, J.; Finan, A.; Weber, K.; Agarwal, U.; Penn, M.S. Myocardial CXCR4 expression is required for mesenchymal stem cell mediated repair following acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2012, 126, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bobi, J.; Solanes, N.; Fernández-Jiménez, R.; Galán-Arriola, C.; Dantas, A.P.; Fernández-Friera, L.; Gálvez-Montón, C.; Rigol-Monzó, E.; Agüero, J.; Ramírez, J.; et al. Intracoronary administration of allogeneic adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells improves myocardial perfusion but not left ventricle function, in a translational model of acute myocardial infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e005771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Díaz-Herráez, P.; Saludas, L.; Pascual-Gil, S.; Simón-Yarza, T.; Abizanda, G.; Prósper, F.; Garbayo, E.; Blanco-Prieto, M.J. Transplantation of adipose-derived stem cells combined with neuregulin-microparticles promotes efficient cardiac repair in a rat myocardial infarction model. J. Control. Release 2017, 249, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseliou, E.; Pollan, S.; Malliaras, K.; Terrovitis, J.; Sun, B.; Galang, G.; Marbán, L.; Luthringer, D.; Marbán, E. Allogeneic cardiospheres safely boost cardiac function and attenuate adverse remodeling after myocardial infarction in immunologically mismatched rat strains. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 61, 1108–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng, K.; Malliaras, K.; Smith, R.R.; Shen, D.; Sun, B.; Blusztajn, A.; Xie, Y.; Ibrahim, A.; Aminzadeh, M.A.; Liu, W.; et al. Human Cardiosphere-Derived Cells From Advanced Heart Failure Patients Exhibit Augmented Functional Potency in Myocardial Repair. JACC Heart Fail. 2014, 2, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marbán, E.; Cingolani, E. Heart to heart: Cardiospheres for myocardial regeneration. Heart Rhythm 2012, 9, 1727–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Chakravarty, T.; Chen, P.; Akhmerov, A.; Falk, J.; Friedman, O.; Zaman, T.; Ebinger, J.E.; Gheorghiu, M.; Marbán, L.; et al. Allogeneic cardiosphere-derived cells (CAP-1002) in critically ill COVID-19 patients: Compassionate-use case series. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2020, 115, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, S.M.; Andreadou, I.; Barile, L.; Birnbaum, Y.; Cabrera-Fuentes, H.A.; Cohen, M.V.; Downey, J.M.; Girao, H.; Pagliaro, P.; Penna, C.; et al. Circulating blood cells and extracellular vesicles in acute cardioprotection. Cardiovasc. Res. 2019, 115, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Guo, D.; Liu, G.; Chen, G.; Hang, M.; Jin, M. Exosomes from MiR-126-Overexpressing Adscs Are Therapeutic in Relieving Acute Myocardial Ischaemic Injury. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 44, 2105–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski, M.P.; Krude, T. Functional roles of non-coding Y RNAs. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2015, 66, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Driedonks, T.A.P.; Mol, S.; de Bruin, S.; Peters, A.L.; Zhang, X.; Lindenbergh, M.F.S.; Beuger, B.M.; van Stalborch, A.M.D.; Spaan, T.; de Jong, E.C.; et al. Y-RNA subtype ratios in plasma extracellular vesicles are cell type- specific and are candidate biomarkers for inflammatory diseases. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambier, L.; De Couto, G.; Ibrahim, A.; Echavez, A.K.; Valle, J.; Liu, W.; Kreke, M.; Smith, R.R.; Marbán, L.; Marbán, E. Y RNA fragment in extracellular vesicles confers cardioprotection via modulation of IL-10 expression and secretion. EMBO Mol. Med. 2017, 9, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.M.; Chien, K.R.; Mummery, C. Origins and Fates of Cardiovascular Progenitor Cells. Cell 2008, 132, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goumans, M.; De Boer, T.P.; Smits, A.M.; Van Laake, L.W.; Van Vliet, P.; Metz, C.H.G.; Korfage, T.H.; Kats, K.P.; Hochstenbach, R.; Pasterkamp, G.; et al. TGF- β 1 induces efficient differentiation of human cardiomyocyte progenitor cells into functional cardiomyocytes in vitro. Stem Cell Res. 2008, 1, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, A.M.; Van Laake, L.W.; Den Ouden, K.; Schreurs, C.; Van Echteld, C.J.; Mummery, C.L.; Doevendans, P.A. Human cardiomyocyte progenitor cell transplantation preserves long-term function of the infarcted mouse myocardium. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2009, 83, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Takahashi, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 2006, 126, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Q.; Jiang, J.; Han, P.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Cao, H.; Meng, Q.; Chen, L.; et al. Direct differentiation of atrial and ventricular myocytes from human embryonic stem cells by alternating retinoid signals. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.H.; Protze, S.I.; Laksman, Z.; Backx, P.H.; Keller, G.M. Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Atrial and Ventricular Cardiomyocytes Develop from Distinct Mesoderm Populations. Cell Stem Cell 2017, 21, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadota, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Shiba, Y. Heart regeneration using pluripotent stem cells. J. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbern, J.C.; Escalante, G.O.; Lee, R.T. Pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes for treatment of cardiomyopathic damage: Current concepts and future directions. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckfeldt, C.E.; Mendenhall, E.M.; Verfaillie, C.M. The molecular repertoire of the “almighty” stem cell. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 726–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fernandes, S.; Chong, J.J.H.; Paige, S.L.; Iwata, M.; Torok-Storb, B.; Keller, G.; Reinecke, H.; Murry, C.E. Comparison of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes, cardiovascular progenitors, and bone marrow mononuclear cells for cardiac repair. Stem Cell Reports 2015, 5, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pascual-Gil, S.; Simon-Yarza, T.; Garbayo, E.; Prosper, F.; Blanco-Prieto, M.J. Cytokine-loaded PLGA and PEG-PLGA microparticles showed similar heart regeneration in a rat myocardial infarction model. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 523, 531–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saludas, L.; Pascual-Gil, S.; Prósper, F.; Garbayo, E.; Blanco-Prieto, M. Hydrogel based approaches for cardiac tissue engineering. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 523, 454–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Ma, A.; Shang, L. Nanoparticles for postinfarct ventricular remodeling. Nanomedicine 2018, 13, 3037–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, D.L.; Lee, R.J.; Coats, A.J.S.; Neagoe, G.; Dragomir, D.; Pusineri, E.; Piredda, M.; Bettari, L.; Kirwan, B.; Dowling, R.; et al. One-year follow-up results from AUGMENT-HF: A multicentre randomized controlled clinical trial of the efficacy of left ventricular augmentation with Algisyl in the treatment of heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2016, 18, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.V.; Zeymer, U.; Douglas, P.S.; Al-Khalidi, H.; White, J.A.; Liu, J.; Levy, H.; Guetta, V.; Gibson, C.M.; Tanguay, J.F.; et al. Bioabsorbable Intracoronary Matrix for Prevention of Ventricular Remodeling After Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 68, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vader, P.; Mol, E.A.; Pasterkamp, G.; Schiffelers, R.M. Extracellular vesicles for drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 106, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Andaloussi, S.; Mäger, I.; Breakefield, X.O.; Wood, M.J.A. Extracellular vesicles: Biology and emerging therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, D.E.; de Jong, O.G.; Brouwer, M.; Wood, M.J.; Lavieu, G.; Schiffelers, R.M.; Vader, P. Extracellular vesicle-based therapeutics: Natural versus engineered targeting and trafficking. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, W.; Khan, M.; Ashraf, M. Extracellular Vesicles From Notch Activated Cardiac Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promote Myocyte Proliferation and Neovasculogenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Jiao, Z.; Dong, N.; Wang, G.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L. Localized injection of miRNA-21-enriched extracellular vesicles effectively restores cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Theranostics 2019, 9, 2346–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.L.; Jiang, H.; Li, C.Y.; Gao, T.; Liu, M.R.; Li, H.W. MicroRNA-338 in MSCs-derived exosomes inhibits cardiomyocyte apoptosis in myocardial infarction. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 10107–10117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yang, R.; Guo, B.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; Li, Y. Exosomal miR-301 derived from mesenchymal stem cells protects myocardial infarction by inhibiting myocardial autophagy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 514, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Qiao, S.; Zhao, J.; Yihai, L.; Qiaoling, L.; Zhonghai, W.; Qing, D.; Lina, K.; Biao, X. miRNA-181a over-expression in mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes influenced inflammatory response after myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Life Sci. 2019, 232, 116632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Lee, C.J.; Deci, M.B.; Jasiewicz, N.; Verma, A.; Canty, J.M.; Nguyen, J. MiR-101a loaded extracellular nanovesicles as bioactive carriers for cardiac repair. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2020, 27, 102201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.H.; Liu, H.; Wang, S.J.; Liang, S.W.; Wang, G.G. Exosomes derived from SDF1-overexpressing mesenchymal stem cells inhibit ischemic myocardial cell apoptosis and promote cardiac endothelial microvascular regeneration in mice with myocardial infarction. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 13878–13893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Liu, X.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, P.; Xu, Y.W.; Liu, Z. Exosomes derived from TIMP2-modified human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells enhance the repair effect in rat model with myocardial infarction possibly by the Akt/SFRP2 pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 1958941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.; Liang, X.L.; Zhang, C.L.; Pang, Y.H.; Lu, Y.X. LncRNA KLF3-AS1 in human mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes ameliorates pyroptosis of cardiomyocytes and myocardial infarction through miR-138-5p/Sirt1 axis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.G.; Li, H.R.; Han, J.X.; Li, B.B.; Yan, D.; Li, H.Y.; Wang, P.; Luo, Y. GATA-4-expressing mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction via secreted exosomes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, J.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, L.; Sun, X.; Zhao, X.; Sun, X.; Qian, H.; Xu, W.; Zhu, W. Exosomes Derived from Akt -Modified Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Improve Cardiac Regeneration and Promote Angiogenesis via Activating Platelet-Derived Growth Factor D. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2017, 6, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ou, H.; Teng, H.; Qin, Y.; Luo, X.; Yang, P.; Zhang, W.; Chen, W.; Lv, D.; Tang, H. Extracellular vesicles derived from microRNA-150-5p-overexpressing mesenchymal stem cells protect rat hearts against ischemia/reperfusion. Aging 2020, 12, 12669–12683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Alimujiang, M.; Chen, Q.; Shi, H.; Luo, X. Exosomes derived from miR-146a-modified adipose-derived stem cells attenuate acute myocardial infarction−induced myocardial damage via downregulation of early growth response factor 1. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 4433–4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciullo, A.; Biemmi, V.; Milano, G.; Bolis, S.; Cervio, E.; Fertig, E.T.; Gherghiceanu, M.; Moccetti, T.; Camici, G.G.; Vassalli, G.; et al. Exosomal expression of CXCR4 targets cardioprotective vesicles to myocardial infarction and improves outcome after systemic administration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Ding, N.; Guan, G.; Liu, G.; Huo, D.; Li, Y.; Wei, K.; Yang, J.; Cheng, P.; Zhu, C. Rapid delivery of Hsa-miR-590-3p using targeted exosomes to treat acute myocardial infarction through regulation of the cell cycle. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2018, 14, 968–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Meng, Q.; Yu, Y.; Sun, J.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, T.; et al. Engineered exosomes with ischemic myocardium-targeting peptide for targeted therapy in myocardial infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e008737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, H.; Yun, N.; Mun, D.; Kang, J.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Park, H.; Park, H.; Joung, B. Cardiac-specific delivery by cardiac tissue-targeting peptide-expressing exosomes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 499, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Song, Y.; Huang, Z.; Chen, J.; Tan, H.; Yang, H.; Fan, M.; Li, Q.; Wang, Q.; Gao, J.; et al. Monocyte mimics improve mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicle homing in a mouse MI/RI model. Biomaterials 2020, 255, 120168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandergriff, A.; Huang, K.; Shen, D.; Hu, S.; Hensley, M.T.; Caranasos, T.G.; Qian, L.; Cheng, K. Targeting regenerative exosomes to myocardial infarction using cardiac homing peptide. Theranostics 2018, 8, 1869–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Erviti, L.; Seow, Y.; Yin, H.; Betts, C.; Lakhal, S.; Wood, M.J.A. Delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haney, M.J.; Klyachko, N.L.; Zhao, Y.; Gupta, R.; Plotnikova, E.G.; He, Z.; Patel, T.; Piroyan, A.; Sokolsky, M.; Kabanov, A.V.; et al. Exosomes as drug delivery vehicles for Parkinson’s disease therapy. J. Control. Release 2015, 207, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, M.S.; Haney, M.J.; Zhao, Y.; Mahajan, V.; Deygen, I.; Klyachko, N.L.; Inskoe, E.; Piroyan, A.; Sokolsky, M.; Okolie, O.; et al. Development of exosome-encapsulated paclitaxel to overcome MDR in cancer cells. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2016, 12, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kanki, S.; Jaalouk, D.E.; Lee, S.; Yu, A.Y.C.; Gannon, J.; Lee, R.T. Identification of targeting peptides for ischemic myocardium by in vivo phage display. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2011, 50, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, S.; Chen, X.; Bao, L.; Liu, T.; Yuan, P.; Yang, X.; Qiu, X.; Gooding, J.J.; Bai, Y.; Xiao, J.; et al. Treatment of infarcted heart tissue via the capture and local delivery of circulating exosomes through antibody-conjugated magnetic nanoparticles. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 4, 1063–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, D.; Ho, E.A. Challenges in the development and establishment of exosome-based drug delivery systems. J. Control. Release 2020, 329, 894–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.T.; Wang, B.; Lv, L.L.; Liu, B.C. Extracellular vesicle-based nanotherapeutics: Emerging frontiers in anti-inflammatory therapy. Theranostics 2020, 10, 8111–8129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Zhang, B.; Ocansey, D.K.W.; Xu, W.; Qian, H. Extracellular vesicles: A bright star of nanomedicine. Biomaterials 2020, 120467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.P.K.; Stevens, M.M. Strategic design of extracellular vesicle drug delivery systems. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 130, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lener, T.; Gimona, M.; Aigner, L.; Börger, V.; Buzas, E.; Camussi, G.; Chaput, N.; Chatterjee, D.; Court, F.A.; del Portillo, H.A.; et al. Applying extracellular vesicles based therapeutics in clinical trials—An ISEV position paper. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 30087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, Y.W.; Kang, M.; Kim, H.Y.; Han, J.; Kang, S.; Lee, J.R.; Jeong, G.J.; Kwon, S.P.; Song, S.Y.; Go, S.; et al. M1 Macrophage-Derived Nanovesicles Potentiate the Anticancer Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 8977–8993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, G.; Lee, J.; Choi, D.S.; Kim, S.S.; Gho, Y.S. Extracellular Vesicle–Mimetic Ghost Nanovesicles for Delivering Anti-Inflammatory Drugs to Mitigate Gram-Negative Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicle–Induced Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, e1801082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhu, C.; Zheng, Q.; Wang, G.; Tong, J.; Fang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Cheng, G.; He, X.; et al. Aptamer-conjugated extracellular nanovesicles for targeted drug delivery. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 798–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Watson, D.C.; Bayik, D.; Srivatsan, A.; Bergamaschi, C.; Valentin, A.; Niu, G.; Bear, J.; Monninger, M.; Sun, M.; Morales-Kastresana, A.; et al. Efficient production and enhanced tumor delivery of engineered extracellular vesicles. Biomaterials 2016, 105, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng, G.; Li, W.; Ha, L.; Han, X.; Hao, S.; Wan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Dong, F.; Zou, X.; Mao, Y.; et al. Self-Assembly of Extracellular Vesicle-like Metal-Organic Framework Nanoparticles for Protection and Intracellular Delivery of Biofunctional Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 7282–7291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wu, Y.; Ding, F.; Yang, J.; Li, J.; Gao, X.; Zhang, C.; Feng, J. Engineering macrophage-derived exosomes for targeted chemotherapy of triple-negative breast cancer. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 10854–10862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Chang, J.; Tian, F.; Zhao, F.; Ma, Y.; Sun, J. Microfluidic Sonication to Assemble Exosome Membrane-Coated Nanoparticles for Immune Evasion-Mediated Targeting. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 7836–7844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangadaran, P.; Hong, C.M.; Ahn, B.C. An update on in vivo imaging of extracellular vesicles as drug delivery vehicles. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pezzana, C.; Agnely, F.; Bochot, A.; Siepmann, J.; Menasché, P. Extracellular Vesicles and Biomaterial Design: New Therapies for Cardiac Repair. Trends Mol. Med. 2020, 27, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaud, M.; Martinez, M.C.; Montero-Menei, C.N. Scaffolds and Extracellular Vesicles as a Promising Approach for Cardiac Regeneration after Myocardial Infarction. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K. Controlled drug delivery systems: Past forward and future back. J. Control. Release 2014, 190, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garbayo, E.; Pascual-Gil, S.; Rodríguez-Nogales, C.; Saludas, L.; Estella-Hermoso de Mendoza, A.; Blanco-Prieto, M.J. Nanomedicine and drug delivery systems in cancer and regenerative medicine. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 12, e1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Gil, S.; Garbayo, E.; Díaz-Herráez, P.; Prosper, F.; Blanco-Prieto, M.J. Heart regeneration after myocardial infarction using synthetic biomaterials. J. Control. Release 2015, 203, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbayo, E.; Gavira, J.; Garcia de Yebenes, M.; Pelacho, B.; Abizanda, G.; Lana, H.; Blanco-Prieto, M.; Prosper, F. Catheter-based intramyocardial injection of FGF1 or NRG1-loaded MPs improves cardiac function in a preclinical model of ischemia-reperfusion. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, K.; Li, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Zhao, J.; Lin, X.; Wang, J.; Zhu, K.; Xiao, C.; et al. Incorporation of small extracellular vesicles in sodium alginate hydrogel as a novel therapeutic strategy for myocardial infarction. Theranostics 2019, 9, 7403–7416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Lee, B.W.; Nakanishi, K.; Villasante, A.; Williamson, R.; Metz, J.; Kim, J.; Kanai, M.; Bi, L.; Brown, K.; et al. Cardiac recovery via extended cell-free delivery of extracellular vesicles secreted by cardiomyocytes derived from induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.W.; Wang, L.L.; Zaman, S.; Gordon, J.; Arisi, M.F.; Venkataraman, C.M.; Chung, J.J.; Hung, G.; Gaffey, A.C.; Spruce, L.A.; et al. Sustained release of endothelial progenitor cell-derived extracellular vesicles from shear-thinning hydrogels improves angiogenesis and promotes function after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 1029–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chung, J.J.; Han, J.; Wang, L.L.; Arisi, M.F.; Zaman, S.; Gordon, J.; Li, E.; Kim, S.T.; Tran, Z.; Chen, C.W.; et al. Delayed delivery of endothelial progenitor cell-derived extracellular vesicles via shear thinning gel improves postinfarct hemodynamics. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 159, 1825–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Physical properties | Size [10] | Small EVs | <100 nm | |

| Small/medium EVs | <200 nm | |||

| Medium/large EVs | >200 nm | |||

| Density (in sucrose) [23] | Low | 1.13–1.19 g/mL | ||

| Medium | 1.16–1.28 g/mL | |||

| High | >1.28 g/mL | |||

| Biochemical composition | Surface antigens [10] | Tetraspanins MHC class I Integrins Transferrin receptor LAMP1/2 Heparan sulfate | Proteoglycans EMMPRIN ADAM10 GPI-anchored 5ʹnucleotidase CD73 Complement-binding proteins CD55 and CD59 Sonic hedgehog | |

| Lipids [10,24] | Phosphatidylserine Phosphatidylinositol Phosphatidylethanolamine Phosphatidylcholine | Cholesterol Ceramide Diacylglycerol Glycosphingolipids | ||

| Internal cargo [10,25,26] | Proteins | TSG101 ALIX VPS4A/B ARRDC1 Flotillins-1 and 2 | Caveolins Annexins Heat shock proteins HSC70 and HSP84 Syntenin | |

| Cardiac-related miRNAs | let-7 miR-16 miR-17-92 miR-19b miR-20a/b miR-21a miR-24 miR-26a miR-34 miR-93 miR-94a miR-107a miR-125b miR-126 | miR-130a/b miR-132 miR-143 miR-145 miR-146a miR-181b miR-182 miR-208a miR-210 miR-214 miR-294 miR-302a miR-451 | ||

| Conditions at EVs harvest | Cell culture conditions [10] | Normoxia Hypoxia Surface coating | Treatment Grade of confluency Passage number | |

| Donor status [10] | Age Biological sex Circadian variation Body mass index | Pathological/healthy condition Exercise level Diet Medication | ||

| Cell Source | Isolation Method | Animal Model | Dose | Administration Route and Time Post-MI | Reparative Effect | Molecule/Mechanism Involved | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSCs | |||||||

| Rat BM-MSCs | Total Exosome Isolation Kit (Invitrogen) | Rat, permanent | 20 µg | IM; immediate |

| - | [62] |

| Mouse BM-MSCs | Density- gradient UC | Mouse, I/R | 50 µg | IM; immediate after reperfusion |

| Inhibition of TLR4 by miR-182 | [63] |

| Proinflammatory rat BM-MSCs | Density-gradient UC | Mouse, permanent | 50 µg | IM; immediate |

| Suppression of NF-κB and regulation of AKT1/AKT2 | [64] |

| BM-MSCs | UC | Rat, permanent | 10 µg EVs (and 2×106 BM-MSCs) | IM; at 30 min |

| - | [65] |

| ATV-pre-treated rat BM-MSCs | UC | Rat, permanent | 10 µg | IM; immediate |

| lncRNA H19 and miR-675 | [66] |

| Mouse BM-MSCs | UC | Mouse, permanent | - | IV; immediate and day 6 |

| miR-210 and Efna3 gene suppression | [67] |

| Mouse BM-MSCs | UC | Mouse, permanent | EVs derived from 2×107 cells | IM; immediate |

| miR-210 | [68] |

| Rat BM-MSCs | Total Exosome Isolation Kit (Invitrogen) | Rat, I/R | 5 µg | IM; prior to reperfusion |

| AMPK and AKT pathways | [69] |

| Mouse BM-MSCs | UC | Mouse, I/R | 12.5 µg/ 5.62×105 EVs | IM; 24h prior to ischemia | • Decreased infarct size | Reduced expression of pro-apoptotic genes PDCD4, PTEN, Peli1 and FasL via miR-21a-5p | [70] |

| Mouse BM-MSCs | UC | Mouse, permanent | 200 µg | IM; immediate |

| miR-125b | [71] |

| BM-MSCs | ExoQuick | Rat, permanent | - | IM; immediate |

| miR-24 | [72] |

| Rat ADSCs | UC | Rat, permanent | 2.5×1012 particles | IV; at 1h |

| S1P/SK1/S1PR1 activation | [73] |

| Rat ADSCs | Ultrafiltration and UC | Rat, I/R | 400 µg | IV; at reperfusion |

| Wnt/β-catenin activation | [74] |

| Human umbilical cord MSCs | Density-gradient UC | Rat, permanent | 400 µg and 800 µg | IV; once daily for 7 days | • Safety: no effect on hemolysis, no vascular and muscle stimulation, no side effects on hematology indexes, liver and renal function, and protective effect on weight loss | - | [75] |

| Human umbilical cord MSCs | ExoQuick-TC (System Biosciences) | Rat, permanent | 400 µg | IM; immediate |

| - | [76] |

| Human umbilical cord MSCs | Density-gradient UC | Rat, permanent | 400 µg | IV; immediate |

| Upregulation of Smad7 by inhibition of miR-125b-5p | [77] |

| Cardiac MSCs | Precipitacion with PEG | Mouse, permanent | 50 µg | IM; immediate |

| - | [78] |

| CDCs | |||||||

| Human CDCs | Ultrafiltration and precipitation with PEG | Pig, I/R | 7.5 mg | IC; 30 min after reperfusion IM; 30 min after reperfusion |

| - | [79] |

| Porcine CDCs | Ultrafiltration followed by Field-Flow Fractionation | Pig, I/R | 9.16 mg | IM; at 72h after reperfusion |

| - | [80] |

| Human CDCs | Ultrafiltration and PEG precipitation | Pig, I/R | 7.5 mg | IM; at 20 min after reperfusion |

| Regulation of gene expression by miRNA | [81] |

| Human CDCs | Ultrafiltration and precipitation with PEG | Rat, I/R | 350 µg | IM; at 30 min after reperfusion |

| - | [81] |

| Human CDCs | ExoQuick (precipitation) | Rat, permanent | 250 µg | IM; at 4 weeks |

| Regulation of gene expression by miRNA | [82] |

| CPCs | |||||||

| Human CPCs | Density-gradient UC | Mice, permanent | 8 µg | IM; at 15 min |

| Activation of endoglin in endothelial cells | [83] |

| Rat CPCs | UC | Rat, I/R | 5 µg/kg | IM; during reperfusion |

| Decreased levels of collagen I, collagen III, vimentin and CTGF Regulation of gene expression via miRNA | [84] |

| Human CPCs | UC | Rat, permanent and I/R | 1011 particles | IM; at 1h after permanent ligation or at reperfusion |

| miR-146a-3p, miR-132, and miR-181a PAPP-A IGF-1 | [85] |

| iPS | |||||||

| Human iPS | UC | Mouse, permanent | 3×1010 particles | Transcutaneous echo-guided IM; at 3 weeks | • Increased cardiac function | Regulation of gene expression via miRNA | [86] |

| Human iPS | UC | Mouse, permanent | 100 µg (1010 particles) | IM; at 2 days or 3 weeks |

| - | [87] |

| Mouse iPS | UC | Mouse, I/R | 100 µg | IM; at 48h after reperfusion |

| Regulation of gene expression via miRNA and metabolic regulation via protein delivery (in silico analysis) | [88] |

| ESC | |||||||

| Human ESC | UC | Mouse, permanent | 20 µg | IM; immediate |

| Targeting miR-497 by lncRNA MALAT1 | [89] |

| Human ESC | UC | Mouse, permanent | - | Transcutaneous echo-guided IM; at 2-3 weeks |

| Gene regulation of DNA repair, cell survival, cell cycle progression and cardiomyocyte contractility (in silico) | [90] |

| Mouse ESC | UC | Mouse, permanent | - | IM; immediate |

| Regulation of CPC cell cycle and association with proliferation and survival mediated by miR-294 | [91] |

| Cell Source | Isolation Method | Modification | Method | Animal Model | Dose | Administration Route and Time Post-MI | Reparative Effect | Mechanism | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cargo loading | |||||||||

| Cardiac MSCs | SEC | Notch1 overexpression | Adenovirus | Mouse, permanent | 2×1010 particles | IM, at 10 min |

| - | [125] |

| HEK293T | UC | miR-21 overexpression | - | Mouse, permanent | 20 µg | IM, immediate |

| PDCD4 | [126] |

| Rat BM-MSCs | Exosome Isolation Reagent (RiboBio) | miR-338 overexpression | Lipofection | Rat, permanent | - | IM, immediate |

| MAP3K2/JNK pathway | [127] |

| Rat BM-MSCs | Exosomes isolation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) | miR-301 overexpression | Lipofection | Rat, permanent | - | IM, at 30 min |

| - | [128] |

| Human umbilical cord MSCs | UC | miR-181a overexpression | Lentivirus | Mouse, I/R | 200 µg | IM, at reperfusion |

| c-Fos inhibition | [129] |

| Human BM-MSCs | Total Isolation Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) | miR-101a overexpression | Electroporation | Mouse, permanent | 2 mg/kg | IV, at days 2 and 3 |

| - | [130] |

| Rat ADSCs | ExoQuick-TC (System Biosciences) | miR-126 overexpression | Lipofection | Rat, permanent | 400 µg | IV, immediate |

| - | [103] |

| Human umbilical cord MSCs | UC | SDF1 overexpression | Lipofection | Mouse, permanent | - | IM, immediate |

| - | [131] |

| Human umbilical cord MSCs | UC | TIMP2 overexpression | Lentivirus | Rat, permanent | 50 µg/ml | IM, immediate |

| Akt/Sfrp2 Pathway | [132] |

| Human MSCs | Exosome isolation kit (Invitrogen) | LncRNA KLF3-AS1 overexpression | Lipofection | Rat, permanent | 40 µg | IV, at 1 week |

| miR-138-5p and Sirt1 | [133] |

| Mouse BM-MSCs | ExoQuick TC (SBI) | GATA4 overexpression | Lentivirus | Mouse, permanent | 20 µg | IV, at 48h |

| - | [134] |

| Human umbilical cord MSCs | Density-gradient UC | Akt overexpression | Adenovirus | Rat, permanent | 400 µg | IV, immediate |

| PDGF-D activation | [135] |

| MSCs | ExoQuick-TC (System Biosciences) | miR-150-5p overexpression | Lentivirus | Rat, I/R | 5.8×1012 particles | IM, at 10 min before reperfusion |

| TXNIP downregulation | [136] |

| Rat ADSCs | ExoQuick (System Biosciences) | miR-146a overexpression | Lipofection | Rat, permanent | 400 µg | IV, immediate |

| EGR1 downregulation | [137] |

| Targeting | |||||||||

| Human CPCs | UC | CXCR4 | Cell lipofection | Rat, I/R | 2×1011 particles | IV, at 3h after reperfusion |

| ERK1/2 activation | [138] |

| Rat BM-MSCs | UC | cTnI-targeted short peptide | Cell electroporation | Rat, permanent | 200 µg | IV, immediate |

| - | [139] |

| Mouse BM-MSCs | Total Exosome Isolation Reagent (Invitrogen) | Cardiac homing peptide (CSTSMLKAC) | Lentivirus transfection of cells | Mouse, permanent | 4×109 particles/50 μg | IV, immediate |

| - | [140] |

| HEK293 | Tangential Flow Filtration | Cardiac targeting peptide (APWHLSSQYSRT) | Cell lipofection | Mouse, no infarct | 150 µg | IV, no infarct | • 15% enhanced heart delivery of EVs | - | [141] |

| Rat BM-MSCs | UC | Monocyte membrane | EVs and monocyte membrane fusion | Mouse, I/R | 10 µg | IV, at days 2 and 3 |

| - | [142] |

| CDCs | Ultrafiltration | Cardiac homing peptide (CSTSMLKAC) | EVs conjugation via a DOPE-NHS linker | Rat, I/R | 6×109 particles | IV, at 24h |

| - | [143] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saludas, L.; Oliveira, C.C.; Roncal, C.; Ruiz-Villalba, A.; Prósper, F.; Garbayo, E.; Blanco-Prieto, M.J. Extracellular Vesicle-Based Therapeutics for Heart Repair. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 570. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11030570

Saludas L, Oliveira CC, Roncal C, Ruiz-Villalba A, Prósper F, Garbayo E, Blanco-Prieto MJ. Extracellular Vesicle-Based Therapeutics for Heart Repair. Nanomaterials. 2021; 11(3):570. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11030570

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaludas, Laura, Cláudia C. Oliveira, Carmen Roncal, Adrián Ruiz-Villalba, Felipe Prósper, Elisa Garbayo, and María J. Blanco-Prieto. 2021. "Extracellular Vesicle-Based Therapeutics for Heart Repair" Nanomaterials 11, no. 3: 570. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11030570

APA StyleSaludas, L., Oliveira, C. C., Roncal, C., Ruiz-Villalba, A., Prósper, F., Garbayo, E., & Blanco-Prieto, M. J. (2021). Extracellular Vesicle-Based Therapeutics for Heart Repair. Nanomaterials, 11(3), 570. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11030570